Abstract

This chapter describes the process of developing an intervention grounded in developmental theory and focused on increasing adolescents’ ethnic-racial identity exploration and resolution. We begin by describing the impetus for the focus on ethnic-racial identity as a target for intervention, which includes a brief overview of prior research identifying consistent associations between developmental features of ethnic-racial identity and adolescents’ positive adjustment. We then review existing intervention efforts focused on identity, generally, and ethnic or cultural identity, specifically. In the second part of the chapter we present our approach for working with a community partner toward the development of the Identity Project intervention, discuss the mixed method (i.e., quantitative and qualitative) approach we used to develop the curriculum, and describe the curriculum. The chapter ends with a discussion of considerations for implementation, including the universal nature of the program and ideas regarding transportability.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Historical Overview and Theoretical Perspectives

Identity development is a significant developmental task that gains momentum and prominence during the developmental period of adolescence (Erikson 1968). Although individuals construct and revisit the conceptualization of their identities throughout the lifespan, it is during adolescence that individuals have the cognitive maturity and social exposure that enables them to more thoroughly explore their goals, values, and beliefs that inform how they define themselves and who they perceive themselves to be in relation to others (Erikson 1968). Individuals’ identities are defined by many social identities, such as those informed by one’s ethnicity, race, or gender (Umaña-Taylor 2011).

In the context of the United States (U.S.), which has a complex history with respect to immigration, racism, and ethnic-racial tensions, ethnicity and race are salient social identities (Umaña-Taylor 2011). Although ethnicity refers to one’s cultural heritage as informed by factors such as traditions and language that get passed on from one generation to the next (Phinney 1996), and race captures sociohistorically-defined phenotypic distinctions based on factors such as skin color and other observable features that have been arbitrarily used to classify individuals in an effort to justify the unfair distributions of resources and power among groups in the US (Helms 1990), these two aspects of individuals’ identities cannot be easily disentangled (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014). As such, the construct of ethnic-racial identity (ERI) captures individuals’ identities as informed by both ethnic features of their ancestral heritage (e.g., cultural traditions, language) and the racialized nature of their group in a particular sociohistorical context (e.g., marginalization as a function of ethnic minority status; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014). The current chapter focuses on ERI, and follows a developmental conceptualization of the construct, such that ERI is defined as a multifaceted construct that includes the extent to which individuals have explored their ethnic background (i.e., ERI exploration), and the degree to which they have achieved a sense of resolution regarding what this aspect of their identity means to them (i.e., ERI resolution; Phinney 1993; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2004). Specifically, the current chapter provides a brief overview of prior work on ERI that provided the impetus for the development of an intervention curriculum focused on this construct as a target for intervention; presents a summary of existing intervention efforts focused on identity, generally, and ERI specifically; describes the mixed-method approach that was used to develop the curriculum for the ERI intervention (i.e., the Identity Project); and provides an overview of the resulting curriculum that was developed. Finally, we end with a discussion of considerations for implementation, including the universal nature of the program and ideas regarding transportability.

Ethnic-Racial Identity Development and Adolescent Adjustment: An Overview

Drawing largely from Erikson’s (1968) psychosocial theory of development, the developmental process of ERI is captured by individuals’ exploration of their ethnic-racial background and their sense of resolution regarding this aspect of their identity. Consistent with conceptualizations of general identity formation (e.g., Erikson 1968), ERI development is believed to evolve throughout the lifespan (Phinney 1996; Syed et al. 2007) but to be particularly salient during the developmental period of adolescence (Phinney 1993). Interest in studying ERI rose dramatically in the early 1990s and has continued to date (Umaña-Taylor 2015); this research activity has resulted in a significant literature base in which scholars have examined the associations between different aspects of adolescents’ ERI and numerous indicators of adjustment (e.g., self-esteem, depressive symptoms, academic adjustment, life satisfaction; see Umaña-Taylor 2011, for a review). Generally, this work has led to the conclusion that, consistent with developmental theory (e.g., Erikson 1968; Marcia 1980), adolescents who have explored the meaning of their ethnic-racial background and have a clearer sense of what this aspect of their identity means for their lives tend to demonstrate better adjustment (e.g., Rivas-Drake et al. 2014). Conceptually, as adolescents have a clearer sense of their identity and have gained this sense of clarity as a result of meaningful exploration of their background, this achieved sense of identity is expected to provide psychological benefits to youth (Phinney and Kohatsu 1997; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2004). Moreover, ERI development is considered a normative developmental task in which youth are expected to engage as part of the process of identity formation, particularly in the context of US where ethnicity and race are salient (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2012).

Given this background, the Identity Project was conceptualized as a universal mental health promotion intervention program. Mental health promotion interventions are typically targeted to a whole population and are designed to enhance individuals’ ability to achieve key developmental competencies (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2009). The Identity Project was designed to be delivered to the general population of youth (i.e., universal), rather than specific to youth identified as being at high risk (i.e., selected) or those showing minimal but detectable signs of problems (i.e., indicated; National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2009). Furthermore, the curriculum was designed to be universal with respect to its relevance to youth from diverse backgrounds, rather than being specific to any one single group; and it is expected to be efficacious for youth from ethnic minority and majority backgrounds. However, because it focuses on a feature of normative development that is particularly salient to ethnic minority youth (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014), it is expected to be especially useful for promoting positive adjustment among ethnic minority youth.

A focus on a normative developmental process such as ERI (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014) as a target for intervention is necessary for several reasons. First, scholars have emphasized the need to capitalize on naturally occurring strengths within ethnic minority communities in efforts to develop more efficacious prevention programming (Case and Robinson 2003); because ERI has been identified as a promotive factor among ethnic minority youth (e.g., Rivas-Drake et al. 2014), it is an ideal source of strength on which to focus. Second, the field of prevention science is limited in its prevention efforts with ethnically diverse populations (Knight et al. 2009), yet a focus on prevention efforts that are particularly relevant to ethnic minority populations is important due to their higher risk for maladjustment coupled with a greater ambivalence regarding seeking services (Case and Robinson 2003; Hollon et al. 2002). Finally, ERI symbolizes a non-stigmatizing and developmentally normative process (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014; Williams et al. 2012), which enables researchers to move away from deficit-focused approaches when intervening with ethnic minority populations.

Current Research Questions

The Prevention Research Cycle and the Development of an ERI Intervention

The prevention intervention research cycle can be divided into four general stages: generative, program development, implementation, and dissemination (Knight et al. 2009; Mzarek and Haggarty 1994; Roosa et al. 1997). The Identity Project is currently reaching the end of the program development stage. Thus, the discussion that follows focuses on the generative stage of the prevention research cycle in which a problem is identified and researchers consider the risk and protective processes that inform the problem or disorder, and the program development stage in which the curricular components of an intervention are developed and refined (see Knight et al. 2009, for a review of the prevention research cycle). Our focus on promoting youths’ engagement in a normative developmental process, which has been linked with positive outcomes among youth and has been demonstrated to buffer the negative impact of risk factors on youth adjustment (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014), is recognized as an important component of the mental health intervention spectrum. Specifically, prevention scientists suggest that promotion efforts focused on the achievement of developmental competencies are crucial because they can strengthen individuals’ ability to cope with adversity, serve as a foundation for future competencies that are necessary for positive adjustment, and ultimately aid in the prevention and treatment of disorders (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine 2009).

The Generative Stage

Extensive reviews of existing theoretical and empirical work on ERI and youth adjustment (e.g., Rivas-Drake et al. 2014; Smith and Silva 2011; Umaña-Taylor 2011; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2004) characterized the generative stage of the Identity Project. A large body of prior theoretical and empirical work has suggested that engagement in exploration and resolution promotes positive adjustment (e.g., psychological well-begin, academic achievement) among ethnic minority (e.g., Neblett et al. 2012; Rivas-Drake et al. 2014) and ethnic majority (e.g., Yasui et al. 2004) youth. Based on a review of this evidence, the first author concluded that there was sufficient consensus to suggest that ERI is a normative developmental process that, importantly, confers psychological benefits for youth when there is evidence of significant engagement in exploration and resolution of one’s ERI. Because of the focus on positive youth development, rather than pathology, there was not a specific problem that was identified, but rather a set of positive outcomes that the literature had identified as ideal for positive youth development (e.g., academic engagement, self-esteem).

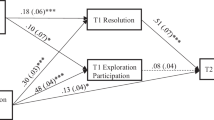

The generative stage of this process also involved developing a theoretical model that described the proximal program mediators that would be targeted in the proposed intervention; the development of this theoretical model was based on prior theoretical and empirical work that has consistently emphasized the importance of operationalizing and measuring ERI exploration and resolution as distinct, yet interrelated, aspects of the ERI formation process (e.g., Supple et al. 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2004, 2014). This prior work informed ERI exploration and resolution as the specific constructs to target in the program (i.e., the modifiable mediators); the initial ideas for the types of activities that would be essential for an ERI intervention; and the age group (i.e., developmental period) that would be targeted with the proposed program (see Fig. 1). The small theory of intervention (i.e., theoretical model guiding the intervention development; Roosa et al. 1997) suggests that a program that effectively provides youth with strategies and tools with which to explore and consider the relevance of their ERI for their general self-concept will, in effect, result in youth engaging in higher levels of ERI exploration and reporting a greater sense of ERI resolution. In turn, engagement in these processes will ultimately be associated with increases in adjustment as indexed by factors such as greater self-esteem, higher school engagement, and more positive orientation toward other ethnic-racial groups. Drawing from Erikson’s (1968) psychosocial theory of development, a possible mechanism by which these positive benefits are conferred is via youths’ more secure sense of self as evidenced by less identity confusion and greater identity cohesion.

The Program Development Stage

After defining the targeted focus of the program, the first author convened a research team that would contribute to the development of the Identity Project curriculum and devise the study design to pilot test the program and examine whether ERI exploration and ERI resolution were, indeed, modifiable mediators. The team included three faculty researchers, a postdoctoral fellow, and several graduate research assistants; together, members of the team represented significant expertise in intervention research, ERI development, and adolescent development. During the early stages of program development, members of the research team met regularly to discuss the type of program and the types of activities that were envisioned, the feasibility of developing and disseminating (i.e., selling to interested stakeholders) a program that targeted normative developmental processes, and the elements of intervention programming that would be essential to consider to ensure that the program was universal (i.e., not targeted to a specific group) and transportable (i.e., the program could be easily implemented as intended in various school settings without major adaptations).

A strong emphasis was placed on certain design elements due to the substantive focus on ERI. First, delivery in a school-based setting, as part of the regular school day, was important to avoid selection bias into the program; if participation were optional, youth who were interested in learning about their ERI may participate and engage with the program in a different manner than their less-interested counterparts. Second, a universal rather than ethnic-racial group-specific approach was important for conceptual and logistical reasons. Conceptually, because ERI development is associated with positive youth adjustment, this is an important developmental competency that should be promoted among all youth, regardless of ethnic-racial background. Furthermore, because ERI is a normative developmental process that is relevant to all youth in ethnically diverse contexts such as the US, the development of a program designed to provide youth with tools, strategies, and ideas for how to explore and consider their commitment toward this aspect of their identity is most consistent with a universal approach; put differently, although the content of one’s exploration may vary across ethnic-racial groups (e.g., learning a specific language, specific group history), the strategies and tools that youth would learn for engaging in exploration activities should not vary across groups. Thus, a universal approach was preferred because it would increase the reach of the program with respect to promoting this important developmental competency among all youth.

With respect to logistics, the ethnic-racial composition of the US is diverse (i.e., 62.6 % White, 17.1 % Latino, 13.2 % Black, 5.5 % Asian and Pacific Islander, 1.2 % American Indian and Alaska Native; US Census 2015) and, likewise, schools in the US vary in their ethnic-racial student body composition. In our experience with school partnerships, school administrators are hesitant to adopt programs that single out a specific ethnic-racial group due to concerns regarding unequal treatment of students, stigmatization of specific groups, and the logistical scheduling difficulties this can present for school personnel. Thus, it was important to develop a program that could be delivered to all youth, regardless of specific ethnic-racial background, which we also believed was more consistent with the ethnic-racial diversity that characterizes the US population. Finally, a universal approach would facilitate the transportability of the program (i.e., the ability for the program to be easily implemented in schools across the US), and this was an important goal given that ERI is an important developmental competency and programs designed to promote ERI should be accessible to youth across the nation.

Overview of Existing Identity Intervention Programming

In addition to determining the design elements noted above, a critical preliminary step in the program development stage involved conducting an exhaustive review of the literature on existing programs to ensure that the envisioned program had not already been developed. Toward this end, an exhaustive review of existing intervention programs was conducted via PsycInfo using 52 unique search queries (detailed table available upon request). Results were screened to identify interventions that targeted identity directly or as a mediating mechanism to affect change in a distal outcome (e.g., academic achievement, psychological health). Results also were screened according to the following criteria: (a) the intervention described was conducted in the US; (b) the work was published in English, though the intervention could be delivered in non-English; and (c) the work appeared in a published source (i.e., dissertations were excluded). Initial screening resulted in 74 results; 14 of these were excluded because they were: (a) conceptual or theoretical papers that did not describe an actual intervention (n = 8), (b) descriptions of curriculum to teach college students about ethnic-racial identity theory rather than curriculum to promote identity processes (n = 2), (c) case studies describing therapeutic approaches (n = 2), (d) recommendations for integrating ethnic and racial readings into literacy curriculum (n = 1), or (e) a parenting intervention designed to promote socialization behaviors within families (n = 1).

The final 60 results were categorized by the target of the program as either general identity interventions (i.e., focus on global identity formation, rather than specifically on ethnic-racial identity) or culturally relevant interventions. General identity interventions (n = 6) included those where specific aspects of social identities were not targeted, whereas culturally relevant interventions (n = 54) included those where issues of ethnicity, race, and/or culture were directly addressed. Although some of the general identity interventions targeted ethnic-racial minority populations through their programming, the programs had to include specific curricular components that directly addressed ethnic, racial, or cultural experiences in order to be considered a culturally relevant intervention.

We also classified the interventions based on specific themes identified within each curriculum to determine if any of the existing programs would be suitable candidates for modification for the Identity Project. Specifically, a basic content analysis of the stated goals of the 60 interventions and their respective curricular components was undertaken, and the interventions could generally be categorized by five fundamental themes: socialization, affirmation, cultural awareness, exploration, and resolution. Socialization programs included those aiming to increase participants’ knowledge of their group, including cultural awareness of one’s own background, socialization, mentoring, transmission of values, and enculturation. Affirmation programs included those aiming to promote positive feelings about one’s identity, including pride and empowerment programs. Cultural awareness programs included those aiming to promote cultural awareness of many groups simultaneously, such as multicultural education programs. Exploration programs included those aiming to promote youths’ self-exploration of their own identity. Finally, resolution programs included those aiming to help youth establish an explicit understanding of their identity. Of note, socialization and exploration themes were distinct in that socialization programs included the explicit sharing and/or providing of information and experiences related to individuals’ ethnic, racial, or cultural heritage, whereas exploration programs included opportunities for youth to seek out such information or create such experiences of their own accord. Each intervention was classified by these themes, and when multiple themes were reflected within a single intervention, the program was jointly classified by all themes reflected in the program. Any interventions that targeted exploration or resolution were carefully reviewed to determine whether they could be modified to meet the goals of the envisioned Identity Project intervention. Below is an overview of the program themes reflected in the General Identity and Culturally Relevant categories of interventions.

Interventions Focused on General Identity

Among the six general identity interventions, two were classified as exploration programs; three were classified as joint exploration and resolution programs; and one could not be classified into any of the five themes because of its unique and exclusive focus on modifying complex cognitive processes (i.e., perspective-taking) with the expectation that this would eventually inform identity formation. Four of the programs (i.e., Berman et al. 2008; Eichas et al. 2010; Ferrer-Wreder et al. 2002; Schwartz et al. 2005) had similar curricular components because all were based on Freire’s (1970/1983) participatory and transformational learning model. The programs were guided by the notion that self-selecting personally important issues and being given the supportive structure to generate solutions to these issues would build feelings of competency which, in turn would promote “informational identity styles” characterized by active exploration (Berzonsky 1989). Although there were slight variations in implementation, the programs were largely consistent in their use of “mastery experiences” in which participants were challenged to identify a problem in their community or their life, and then encouraged to generate a solution with guidance and support from intervention leaders.

Program participants were typically assigned to small groups consisting of 6–9 students, and each small group was facilitated by at least two leaders (in some cases, a clinician; Berman et al. 2008). The groups met once per week, with extensive small group discussions of self-identified problems, and one participant’s problem discussed in depth each week. Generally, participants worked on generating a solution to a self-identified problem, considering multiple strategies or options with which to tackle the problem. The programs varied in their length of time, because the program was designed to end after each group participant had worked through his or her problem solving process. Thus, some programs lasted only 8 weeks (e.g., Eichas et al. 2010), whereas others lasted 15 weeks (e.g., Berman et al. 2008).

Findings from three of the four studies that used the mastery experiences approach suggested that identity exploration was modifiable via curricula designed to engage youth in seeking information in a supportive context. Although these programs did not focus specifically on exploration of ethnicity or race, and the design features of the curriculum (e.g., low leader to participant ratio; small group setting; delivery of the program by a trained clinician; participant-led sessions) were not feasible given the goals of the Identity Project to develop a program that could be delivered in a classroom setting by a single teacher, the findings were encouraging with respect to whether identity exploration was a modifiable target for intervention.

The fifth program within the general identity category (i.e., Howard and Solberg 2006) exclusively targeted exploration among high school students, and was heavily tailored toward students’ academic identities. Its curriculum, which was delivered approximately once every 2 weeks over the course of two grading periods, focused on the interface of student identities and school settings. A four-part series of activities were implemented to: (a) allow students to share their own life perspectives in a safe and validating environment, (b) provide individual assessment of their academic issues and barriers to success, (c) teach youth how to set achievable, concrete academic goals, and (d) promote positive social interactions. Program effects for high school students in an urban, low-income community included benefits in grades, attendance, and credit earnings (Howard and Solberg 2006). The curricular component within this program and the aforementioned programs that focused on providing a safe space within which to share and consider their own life perspectives was consistent with a goal of the Identity Project to provide students with a safe context within which to explore and consider the multifaceted nature of their identity. Other than this, however, our review revealed that a relatively simple modification of an existing program was not possible to achieve the goals of the Identity Project focused on targeting exploration and resolution of ERI.

Interventions Focused on Culturally Relevant Dimensions of Identity

The 54 culturally relevant interventions identified in our review were classified based on the following foci: socialization (n = 28), cultural awareness (n = 8), affirmation (n = 6), and exploration (n = 1). Several programs captured two foci: socialization and affirmation (n = 7), cultural awareness and exploration (n = 2), socialization and cultural awareness (n = 1), and affirmation and exploration (n = 1). Thus, no culturally relevant interventions captured both intended processes for the Identity Project (i.e., exploration and resolution). Nevertheless, we carefully reviewed the curriculum and program effects for the four interventions that included exploration in considering the Identity Project curriculum. Because these programs, relative to the general identity programs, were more directly related to the substantive topic on which the Identity Project focused (i.e., ethnic-racial identity), several aspects of program content were relevant to our goals and we ultimately adopted modified versions of these, as described below.

Of the four programs we reviewed in depth, one was an experience-based intervention designed to facilitate African American and Mexican American adolescents’ exploration through civil rights education (Bettis et al. 1994). Students received direct instruction on the history of African American and Mexican American civil rights in the United States that included watching civil rights documentaries, reading civil rights literature, and writing essays. The main focus of the program was a 2-week field trip through the Southern US that included visits to prominent civil rights sites such as Little Rock, Arkansas, and San Antonio, Texas. In addition to visiting historical sites, participants also interviewed individuals who were directly involved in the civil rights movement. The program was evaluated qualitatively, with students reporting themes that reflected a broadened perspective on civil rights, a personal connection to the civil rights movement, and a greater personal awareness of the meaning of ethnicity in their lives after taking part in the program; overall, findings suggested that the program had achieved its goals. Although the program’s culture-specific approach (i.e., African American and Mexican American adolescents) and the time and cost-intensive nature of the program were incompatible with our goals for the Identity Project, the component of the curriculum in which students interviewed individuals with whom they shared an ethnic background was a compelling activity that we believed could be implemented in the Identity Project to facilitate ERI exploration; furthermore, this could be easily adapted to our proposed setting (e.g., participants could interview someone with whom they shared an ethnic background as part of a homework assignment). Therefore, a modified version of this activity was subsequently included in the Identity Project curriculum.

A second program used an intergroup dialogue framework in which discussion of ethnic and racial issues between groups was used to facilitate development of youths’ own ERI (Aldana et al. 2012). In this program, youth from various ethnic-racial backgrounds (i.e., African American, Asian American, European American, Latino American, and Middle Eastern American) came together to discuss issues within and across their communities over the course of 8 weeks, culminating in a weekend retreat focused on youth activism and social advocacy skills. Program effects included significant increases in ERI exploration among youth from low socioeconomic families, but not among youth from high socioeconomic families, and no overall changes in ERI identity resolution. The program also appeared to influence awareness of racial issues, as youth participants reported significant increases in awareness of privilege, discrimination, and blatant racial issues. The intervention relied on intergroup dialogue as a proxy for self-exploration, which was a natural fit with the overall framework of the Identity Project and its envisioned universal approach; thus, this program element was incorporated into the Identity Project curriculum.

The third program was a graduate school curriculum that targeted exploration among therapists-in-training, with the assumption that promoting exploration would improve cultural competencies in therapeutic settings (Spears 2004). It was tested with a predominantly White sample of graduate students, and focused largely on understanding bias, prejudice, and discrimination. The curriculum included lectures, guest speakers, videos, readings, journaling, class discussion, and self-disclosure around issues of inequality. Although the goal of the program (i.e., therapeutic cultural competencies) and program contents were largely incompatible with our focus on the developmental period of adolescence, one program component appeared relevant and easily adaptable to the Identity Project. Specifically, in a Heritage Photo Sharing exercise, students created visual representations of their cultural selves through pictures, drawings, or paintings, and shared their creation with others. The activity was designed to increase awareness of cultural and racial identity of both the self and others; qualitative findings suggested that the activity resulted in increased sensitivity and knowledge about people from different ethnic backgrounds. Given its relevance, a modified version of this activity was incorporated into the Identity Project curriculum.

The final program was a therapy-based intervention designed to promote racial identity of White adults in the context of racial consciousness (i.e., Regan and Scarpellini Huber 1997). Components of the program included recognizing matters of privilege afforded by Whiteness, identifying and connecting to components of White culture, making implicit racial experiences explicit, and racism education. Although its culture-specific content, focus on adults, and therapeutic approach limited its relevance to the Identity Project, the authors’ reflection of the effects of the program suggested that the program was effective in engaging individuals in the process of exploration of their ERI.

In sum, the review of the culturally relevant interventions targeting exploration revealed that while there were a select number of curriculum components that would be appropriate for the Identity Project, there was no single program that was developmentally appropriate or that targeted both ERI components of interest. Taken together, however, findings from both the general identity and culturally relevant programs did support targeting ERI exploration. The focus on resolution was more limited and the review provided little information in this regard.

Research Measurement and Methodology

The Identity Project Curriculum: Engaging a Community Partner

After determining that we would indeed be developing a curriculum and pilot testing a new program, we initiated the process of finding a community partner. As noted above, a primary goal was to develop a universal school-based program; thus, we searched for schools that had high rates of ethnic diversity in their student body, with school diversity being operationalized by Simpson’s Index of Diversity (see Juvonen et al. 2006). This index of diversity gives higher scores to schools with a more diverse representation of ethnic backgrounds, rather than focusing exclusively on the ethnic majority to ethnic minority student ratio to classify a school’s degree of diversity. The school with which we eventually partnered for the development of the Identity Project curriculum and pilot testing had a Simpson’s Index of Diversity score of 0.66, which is considered a school with high diversity (Juvonen et al. 2006). Specifically, the ethnic composition of the student body was 46.8 % White, 26.5 % Latino, 15.6 % Black, 4.6 % Asian, 2.6 % American Indian/Native American, and 3.9 % other.

After identifying potential partner schools (i.e., based on the ethnic diversity of the student population), we scheduled appointments with school administrators to discuss the goals of our project. When meeting with administrators, we explained that our purpose was to partner with their school to develop an intervention program focused on providing students with tools and strategies with which to explore their ethnic background and gain a clearer sense of the personal meaning that their ERI has for them. For each school with which we had scheduled meetings, we researched the school’s mission statement and academic goals and made sure to explain how our focus in the Identity Project was related to advancing the school’s stated goals and/or mission statement.

In our meetings with administrators, we also emphasized that we viewed our work together as a collaborative effort. Because we were aiming to develop a program that could be administered in the school setting (eventually as part of the school curriculum and to be delivered by teachers), fully engaging with our community partner of school administrators and teachers was essential for developing a program that would ultimately meet the intended goals of the program (see Bogart and Uyeda 2009, for a review). Furthermore, this initial groundwork, in which school administrators and teachers are involved at the onset of program development, is critical for increasing the sustainability of programs after the research team leaves (Jenson et al. 1999). After the community partner had been identified (and agreed to partner with our research team), we initiated the data collection process that would inform the development and refinement of the Identity Project curriculum.

The Identity Project: Phases of Curriculum Development

In the current section we describe the mixed-method approach that we used to inform the specific features of the Identity Project curriculum. Because the primary goal of the Identity Project intervention was to increase adolescents’ ERI exploration and resolution, we sought information directly from adolescents regarding the best ways to engage young people of their same age group in a program designed to involve youth in the process of ERI development. This required gathering data from adolescents who were already reporting high levels of exploration and resolution (i.e., to better understand adolescents’ own perceptions of how they might have achieved their high levels of exploration and resolution), as well as gathering data from adolescents who were reporting low levels of exploration and resolution (i.e., to better understand potential barriers that they may have faced in the context of exploring or coming to a sense of resolution regarding their ERI). Toward this end, we followed a two-step mixed-method approach in which we initially gathered quantitative data on adolescents’ levels of ERI exploration and resolution, and then used the data from the survey responses to purposefully recruit adolescents into focus groups where we would gather more in-depth information regarding adolescents’ experiences with ERI.

Survey Data Collection

In the quantitative survey phase of this process, we gathered data from over 1500 adolescents from our target school. The purpose of the large-scale data collection was to quantitatively assess adolescents’ ERI exploration and resolution and basic demographic characteristics, and to use this information to selectively recruit youth (based on their ethnicity, grade level, and ERI scores) into the qualitative portion of the study. We gathered data from the entire student body during school hours to minimize selection bias in this initial quantitative phase of the study. This design feature was important because, in an effort to develop a universal program, it was necessary to engage youth from all ethnic backgrounds and youth at all levels of the ERI formation process. Furthermore, data were collected during school hours to minimize barriers against participation (e.g., requiring students to stay after school or come early, conflicting with extracurricular activity involvement).

In the quantitative phase we assessed students’ ERI exploration and resolution using the Ethnic Identity Scale (EIS; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2004). The aim of the focus groups was to purposefully target youth who were at different stages of the ERI formation process. To inform recruitment for the focus groups, therefore, we followed a three-step procedure to stratify the sample by ethnicity, grade level, and finally ERI. First, participants were stratified by ethnic-racial self-identification based on the four largest groups represented in the sample (Latino, Black, White, and Asian). Next, within each ethnicity, participants were stratified based on grade level, with 9th and 10th grade students grouped together and 11th and 12th grade students grouped together. These two levels of stratification resulted in eight distinct groups (i.e., for each ethnicity there was a 9th/10th grade group and a 11th/12th grade group). Finally, to classify individuals into high versus low ERI exploration and resolution groups, cluster analyses were conducted individually for each group (with the exception of Asian 9th/10th grade students, as there were only 16 students who fell into this category, which was an inadequate sample size for cluster analysis).

Both exploratory (two-step) and confirmatory (k-means) cluster analyses were conducted to optimize the chance of finding the best-fitting solution for each grouping. With cluster analysis, we identified students within each ethnic group and grade stratification that scored low on both ERI exploration and resolution, and those who scored high on both dimensions. This resulted in a total of 14 categories (Table 1).

Focus Group Data Collection

The targeted sample size for each focus group was 7–8 participants; however, a larger number of students fell into each of the 14 categories that would be used to populate each focus group. Therefore, a random number generator was used to produce a unique set of 20 numbers for each of the fourteen groups. Within each group, these numbers were matched to the data file row to identify participants for recruitment. A total of 20 possible participants were selected for each focus group in case students refused to participate or did not respond to recruitment attempts. During recruitment, the first eight participants were contacted through phone calls and letters distributed through the schools. If participants indicated that they did not want to participate or if they did not respond to any of the recruitment attempts, the next person on the list was contacted. We attempted to contact 170 students for participation in the focus groups. We were unable to reach 46 students (i.e., 27 %); of the 124 students who we reached, 79 % participated (n = 98), 8 % refused participation (n = 10), and 13 % agreed to participate but did not arrive at the scheduled time (n = 16).

Focus groups took place during a study period during regular school hours, to minimize barriers to participation. Furthermore, as recommended by Morgan (1997), group composition was carefully considered with respect to homogeneity on a number of demographic factors. Specifically, focus groups were homogeneous with respect to developmental period to minimize younger students (e.g., 9th graders) feeling uncomfortable speaking up in the presence of significantly more advanced students (e.g., 12th graders). For logistical reasons, we were unable to conduct focus groups for each distinct grade; however, we grouped middle adolescents with one another (i.e., 9th and 10th graders) and late adolescents (11th and 12th graders) with one another. Similarly, focus groups were homogeneous with respect to ethnicity, given that the discussions were focused on ethnic-related experiences and we wanted to minimize potential barriers to speaking up about personal experiences in the context of peers from other ethnic groups. Due to sample size constraints for smaller groups (e.g., Asians), we were unable to make groups homogeneous with respect to gender. Group discussions lasted 60–90 min, and were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. All focus groups were moderated by the first or second author; in addition, a note taker was present during each focus group to facilitate later transcription. At the end of each focus group, each adolescent received $10 for their participation.

The focus group protocols were tailored to the ERI exploration and resolution experiences of participants based on their responses to the survey questions. This phase of the process was critical because it enabled students to voice their opinions and experiences with respect to exploring and resolving issues surrounding their ERI, in their own words. Using this information to develop and refine the Identity Project curriculum was essential for creating a program that was relevant, meaningful, and empowering to high school students. Specifically, adolescents who scored high on ERI exploration and resolution were recruited to take part in a focus group that focused on what their experiences had been with respect to learning about their ethnicity and having a sense of clarity about the meaning that their ethnicity had for them. We asked adolescents to think about how they had learned about their ethnic background and to discuss experiences that were salient to them. Additionally, adolescents who scored low on ERI exploration and resolution were recruited to participate in focus group discussions designed to inquire about potential barriers to engaging in processes of exploration and resolution regarding ERI. Finally, adolescents in all groups were asked to generate and share ideas regarding activities that (from their perspective) would inform youth about their ethnic background and that students in high school would be interested in doing. The focus group setting was ideal for gathering these data because students bounced ideas off of each other; sometimes a comment made by one student prompted another student to remember something they had not yet shared, and other times students disagreed with one another and offered varied perspectives on the topic of interest.

Development and Refinement of Curriculum

Data gathered during the focus group discussions were used in conjunction with prior research to inform the lessons that would eventually make up the curriculum for the Identity Project. We began with a general idea of the types of activities that would be included in the program and global objectives based on theoretical and empirical literature, including our review of existing intervention programs; but the information gleaned from adolescents in the focus groups helped to finalize the primary objectives for each lesson and to provide specific ideas for activities to include in the program. As one example, during our focus group discussions, students consistently raised the concern that there are many misconceptions about specific ethnic groups, and that there are many generalizations made about pan-ethnic groups (e.g., generalizations about Asians, versus understanding the diversity that exists within Asian subgroups). This was consistent with program content we had identified in our review (e.g., discussions of discrimination or racism; Aldana et al. 2012). Thus, the focus group data supported our inclusion of this program element in the curriculum and, as described below, one of the eight sessions in the Identity Project program focuses on defining and discussing terms such as stereotypes and discrimination, as well as on understanding within and between group differences.

As a second example, many focus group participants noted that they had learned about their ethnicity by being exposed to information about others’ ethnic groups; learning about others’ ethnicity often led students to examine or think about their own ethnic backgrounds in relation to what they had learned or been exposed to about someone else’s ethnic group. This mirrored a program component that emerged in our review (i.e., Spears 2004), in which participants learned about the self and others via various activities in which they explored their backgrounds, and presented the information they had learned to other participants in the program. Accordingly, as we developed and refined the Identity Project curriculum, we integrated many opportunities for students to share the information that they were learning about their own ethnic background(s) with their classmates.

In other instances, findings from the focus group provided novel ideas with respect to activities that would promote the ERI formation processes of exploration and resolution. For example, focus group participants noted that learning about race and ethnicity from the perspectives of other young people who came to their schools as guest speakers or visitors, or who were telling their stories in movies, was very informative and interesting. Based on this information, we developed a video in which we presented interviews with several young adults who represented different ethnic-racial backgrounds and experiences, and chronicled their individual journeys with respect to their ERI development from when they were young children until the present time. Thus, the focus group data were used to refine ideas that we developed based on reviewing existing programs, considering the theoretical literature, and to develop new ideas that would be incorporated into the Identity Project curriculum.

After carefully revising and finalizing the curriculum based on the focus group data, the second author delivered each lesson to a small ethnically diverse group of 8 graduate research assistants and staff, which represented a group with varied levels of education (e.g., high school graduate, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree) as well as varied expertise in adolescent development and ERI. All sessions were videotaped, and we asked research staff to engage with the program as fully as possible, including completing all of the homework assignments. At the end of each lesson, the members of the research team discussed aspects of the lesson that seemed to work well, aspects that may not work well with the targeted population of high school students, and any other observations about the program or specific activities. Each session was videotaped and the first author carefully reviewed the videos and revised the curriculum content based on observations of how the lesson went, as well as based on the feedback that emerged during the research team’s large group discussion at the end of each lesson. All lessons were reviewed at least two more times independently by both authors; the authors met regularly to discuss revisions and to decide on the final changes necessary before pilot testing. In the section that follows, we provide an overview of the curriculum.

Introduction to the Identity Project Curriculum

The Identity Project curriculum consists of an 8-week program designed to engage youth in the developmental processes of ERI exploration and ERI resolution by increasing students’ salience and understanding of their ethnic heritage(s) and background(s), as well as others’ backgrounds; increasing students’ awareness and understanding of multiple groups’ experiences with discrimination in the context of the US across different historical periods; exposing students to the notion that differences within groups are oftentimes larger than differences between groups; engaging students in activities designed to increase their understanding of their family heritage, regardless of how they define “family;” clarifying misconceptions students may have regarding a “right or wrong” way to identify with an ethnic group, and providing students with examples of diverse journeys for ERI development; providing students with tools with which to explore their ethnic heritage (e.g., making them aware of symbols, traditions, and rituals, and ways to learn more about these); and providing opportunities for students to discuss their heritage with others. These goals are achieved via 8 lessons.

The Identity Project was designed to be a school-based intervention program that is delivered over an 8-week period, with weekly lessons that last approximately 55 min each. We developed all activities and lesson plans in a manner such that they could be delivered and implemented by a single leader, given that the ultimate goal is to have this program delivered in the school setting by a teacher or other school personnel. Starting in Week 2, students have homework assignments that relate to content they have learned about in the lesson, or in which they are gathering information and/or preparing materials that will be used in a subsequent lesson.

Throughout the 8 weeks, students participate in small group activities, large group activities, and complete individual work that is almost always shared in a larger group setting. Program materials include PowerPoint slides with key terms and definitions, video clips, worksheets, and ice breakers designed to help students feel comfortable sharing their experiences with their classmates and the instructor. Finally, the program also includes opportunities for students to explore their ethnic backgrounds by interviewing family members or members of their communities.

Future Directions

The Identity Project is currently in the pilot testing phase, which captures the final stages of program development within the prevention research cycle. We are piloting the program in 9th grade classrooms within our partner high school. A total of 8 classrooms have been randomized into the treatment condition (i.e., Identity Project curriculum) or an attention control condition in which the authors are delivering a curriculum that is focused on exposing students to educational and career opportunities after obtaining a high school degree. The classrooms were selected in consultation with our school partner and reflect all freshmen who are enrolled in an elective course focused on providing students with skills that will help them adapt to and succeed in the high school setting (e.g., computer skills, developing good study habits). Targeting 9th grade students is ideal for developmental reasons (i.e., middle adolescence has been identified as a period in which ERI processes are heightened; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014), but also because 9th grade students will not have participated in any of the preliminary data collection efforts that took place the year prior when the research team was gathering survey and focus group data to inform the development of the curriculum.

In the pilot testing phase, we are examining the feasibility of delivering the program in an ethnically diverse school setting, assessing the extent to which students engage with the program content, and evaluating whether the content appears developmentally appropriate. With this small-scale efficacy trial, we are testing whether there are trends suggesting that participation in the program is indeed leading to greater changes in ERI exploration and resolution among youth in the treatment versus attention control conditions. Furthermore, the effect sizes we identify in the pilot testing phase will enable us to determine the sample size necessary to have sufficient power to test effects in a large-scale efficacy trial. We also will be able to examine whether effect sizes appear to vary based on demographic characteristics (e.g., student ethnicity, generational status). These preliminary data will be essential for informing the development of a large-scale efficacy trial of the program.

Given that the program is in its initial stages of development and implementation, we are limited in what we can say with respect to future implementation and feasibility of transportability. However, in developing the program, we have focused on ensuring that the activities and the lessons are relevant and accessible to students with diverse ethnic backgrounds (e.g., multiethnic) and diverse family constellations (e.g., youth being raised by one parent and having limited to no knowledge about a second parent; youth being raised by extended family members or by adoptive parents). We also developed the lessons to be relevant to participants regardless of the ethnic composition of the students in the classroom (e.g., many examples in the lessons are generated by student participants’ experiences and backgrounds, rather than being predetermined in the curriculum). Because our program is designed to engage youth in the process of ERI formation, which focuses on increasing exploration and developing a clearer sense of resolution regarding one’s background, the program does not focus on teaching students about any particular group. Thus, the focus on providing tools with which to engage in the process, rather than providing content about any specific group, lends itself well to delivering the program in multiple settings. We expect that the program will be relevant and easy to administer without adaptations in ethnically diverse school settings where many different ethnic-racial groups are represented as well as in school settings that are less diverse.

Finally, as we consider efficacy testing and further development of the Identity Project, an important idea to consider is whether program effects might be moderated by contextual factors that could strengthen the program’s efficacy. For example, because greater salience of ethnicity is expected to increase adolescents’ engagement in ERI development processes (Umaña-Taylor et al. 2014), and prior work has demonstrated that ethnicity is more salient in contexts in which one’s ethnic group is a numerical minority (Umaña-Taylor 2004), it will be interesting to examine moderation of program efficacy by context. Perhaps program effects will be strongest in settings that are increasingly ethnically diverse, as ethnicity may be especially salient in such settings. Similarly, given the significant role that families play in socializing youth about ethnicity (Hughes et al. 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2009), it will be interesting to examine if youths’ experiences with family ethnic socialization modify program effects such that youth who report high levels of family ethnic socialization demonstrate relatively stronger program effects than youth reporting lower levels of family ethnic socialization.

References

Aldana, A., Rowley, S. J., Checkoway, B., & Richards-Schuster, K. (2012). Raising ethnic-racial consciousness: The relationship between intergroup dialogues and adolescents’ ethnic-racial identity and racism awareness. Equity and Excellence in Education, 45(1), 120–137. doi:10.1080/10665684.2012.641863

Berman, S. L., Kennerley, R. J., & Kennerley, M. A. (2008). Promoting adult identity development: A feasibility study of a university-based identity intervention program. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 8(2), 139–150. doi:10.1080/15283480801940024

Berzonsky, M. D. (1989). Identity style: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Adolescent Research, 4(3), 268–282.

Bettis, P. J., Cooks, H. C., & Bergin, D. A. (1994). “It’s not steps anymore, but more like shuffling”: Student perceptions of the civil rights movement and ethnic identity. Journal of Negro Education, 63(2), 197–211.

Bogart, L. M., & Uyeda, K. (2009). Community-based participatory research: Partnering with communities for effective and sustainable behavioral health interventions. Health Psychology, 28, 391–393.

Case, M. H., & Robinson, W. L. (2003). Interventions with ethnic minority populations: The legacy and promise of community psychology. In G. Bernal, J. E. Trimble, A. K. Burlew, & F. T. L. Leong (Eds.), Handbook of racial and ethnic minority psychology (pp. 573–590). Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

Eichas, K., Albrecht, R. E., Garcia, A. J., Ritchie, R. A., Varela, A., Garcia, A., et al. (2010). Mediators of positive youth development intervention change: Promoting change in positive and problem outcomes? Child and Youth Care Forum, 39(4), 211–237. doi:10.1007/s10566-010-9103-9

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Ferrer-Wreder, L., Lorente, C. C., Kurtines, W., Briones, E., Bussell, J., Berman, S., et al. (2002). Promoting identity development in marginalized youth. Journal of Adolescent Research, 17(2), 168–187. doi:10.1177/0743558402172004

Freire, P. (1970/1983). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder & Herder.

Helms, J. E. (1990). Introduction: Review of racial identity terminology. In J. Helms (ed.), Black and white racial identity (pp. 3–8). Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Hughes, D., Rodriguez, J., Smith, E. P., Johnson, D. J., Stevenson, H. C., & Spicer, P. (2006). Parents’ ethnicracial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 747–770. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747

Hollon, S. D., Muñoz, R. F., Barlow, D. H., Beardslee, W. R., Bell, C. C., Bernal, G., et al. (2002). Psychosocial intervention development for the prevention and treatment of depression: Promoting innovation and increasing access. Biological Psychiatry, 52, 610–630.

Howard, K. A. S., & Solberg, V. S. (2006). School-based social justice: The achieving success identity pathways program. Professional School Counseling, 9(4), 278–287.

Jenson, P. S., Hoagwood, K., & Trickett, E. J. (1999). Ivory towers or earthen trenches: Collaborations to foster real-world research. Applied Developmental Science, 3(4), 206–212.

Juvonen, J., Nishina, A., & Graham, S. (2006). Ethnic diversity and perceptions of safety in urban middle schools. Psychological Science, 17, 393–400.

Knight, G. P., Roosa, M. W., & Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2009). Methodological challenges in studying ethnic minority or economically disadvantaged populations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 159–187). New York: Wiley.

Morgan, D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Mzarek, P. J., & Haggerty, R. J. (1994). Reducing risks for mental health disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

National Research Council & Institute of Medicine (2009). Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities. Committee on the prevention of mental disorders and substance abuse among children, youth, and young adults: Research advances and promising interventions. M. E. O’Connell, T. Boat, & K. E. Warner (Eds.). Board on Children, Youth, and Families, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Neblett, E. W., Jr., Rivas-Drake, D., & Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2012). The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 295–303.

Phinney, J. S. (1993). A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. In M. E. P. Bernal & G. P. Knight (Eds.), Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities (pp. 61–79). NY: SUNY Press.

Phinney, J. S. (1996). When we talk about American ethnic groups, what do we mean? American Psychologist, 51, 918–927.

Phinney, J. S., & Kohatsu, E. L. (1997). Ethnic and racial identity development and mental health. In J. Schulenberg, J. L. Maggs, & K. Hurrelmann (Eds.), Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence (pp. 420–443). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Regan, A., & Scarpellini Huber, J. (1997). Facilitating White identity development: A therapeutic group intervention. In C. Thompson & R. Carter (Eds.), Racial identity theory: Applications to individual, group, and organizational interventions (pp. 113–126). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Rivas-Drake, D., Seaton, E. K., Markstrom, C., Quintana, S., Syed, M., Lee, R., et al. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85, 40–57.

Roosa, M. W., Wolchik, S. A., & Sandler, I. N. (1997). Preventing the negative effects of common stressors: Current status and future directions. In S. A. Wolchick & I. N. Sandler (Eds.), Handbook of children’s coping: Linking theory and intervention (pp. 515–533). New York: Plenum.

Schwartz, S. J., Kurtines, W. M., & Montgomery, M. J. (2005). A comparison of two approaches for facilitating identity exploration processes in emerging adults: An exploratory study. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20(3), 309–345. doi:10.1177/0743558404273119

Smith, T. B., & Silva, L. (2011). Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 42–60.

Spears, S. S. (2004). The impact of a cultural competency course on the racial identity of MSWs. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 74(2), 272–288. doi:10.1080/00377310409517716

Supple, A. J., Ghazarian, S. R., Frabutt, J. M., Plunkett, S. W., & Sands, T. (2006). Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development, 77, 1427–1433.

Syed, M., Azmitia, M., & Phinney, J. S. (2007). Stability and change in ethnic identity among Latino emerging adults in two contexts. Identity An International Journal of Theory, 7, 155–178.

Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2011). Ethnic Identity. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 791–809). New York: Springer.

Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2015). Ethnic identity research: How far have we come? In C. E. Santos & A. J. Umaña-Taylor (Eds.), Studying ethnic identity: methodological and conceptual approaches across disciplines (pp. 11–26). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Alfaro, E. C., Bámaca, M. Y., & Guimond, A. B. (2009). The central role of familial ethnic socialization in Latino adolescents’ cultural orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 46–60.

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Yazedjian, A., & Bámaca-Gómez, M. Y. (2004). Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 4, 9–38.

Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Quintana, S. M., Lee, R. M., Cross, W. E., Rivas-Drake, D., Schwartz, S. J., et al. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity revisited: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85, 21–39.

U.S. Census Bureau (2015). State and County QuickFacts. Data derived from Population Estimates, American Community Survey, Census of Population and Housing, State and County Housing Unit Estimates, County Business Patterns, Nonemployer Statistics, Economic Census, Survey of Business Owners, Building Permits. Last Revised: March 31, 2015. Retrieved from: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html

Williams, J. L., Tolan, P. H., Durkee, M. I., Francois, A. G., & Anderson, R. E. (2012). Integrating racial and ethnic identity research into developmental understanding of adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 304–311.

Yasui, M., Dorham, C. L., & Dishion, T. J. (2004). Ethnic identity and psychological adjustment: A validity analysis for European American and African American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 807–825.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 The Editor(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Umaña-Taylor, A.J., Douglass, S. (2017). Developing an Ethnic-Racial Identity Intervention from a Developmental Perspective: Process, Content, and Implementation of the Identity Project. In: Cabrera, N., Leyendecker, B. (eds) Handbook on Positive Development of Minority Children and Youth. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43645-6_26

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43645-6_26

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-43643-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-43645-6

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)