Abstract

Self-reported ethnic labels were examined among 242 young American adults with Chinese ancestry (age range = 18–32 years, M = 23.97; 73% female, 27% male). Ethnic labels fell under broad categories whereby 22% reported heritage national labels (e.g., Chinese), 35% added American to their heritage national label (e.g., Chinese American), and 42% reported panethnic-American labels (e.g., Asian American). Logistic regressions revealed that generation and ethnic exploration significantly predicted the odds of choosing heritage national and heritage national-American labels. Ethnic label choice was not associated with average differences in the ethnic diversity of youths’ community or peer group, or with heritage language proficiency. However, label choice was associated with generation, ethnic identity, and English proficiency. Ethnic labels also were linked to self-esteem and positive relationships with Asian peers, with most optimal outcomes reported by youth who chose heritage national-American labels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A unique aspect of human nature requires youth to decide what social categories they fit into and with which social groups to align themselves. Although self-categorization appears to be a rather simple process, the types of labels that young adults use to define themselves can vary widely and have deep implications for development. More specifically, ethnic self-identification refers to one’s understanding and knowledge of one’s ethnic group membership (Phinney 1992), and has been linked to a number of psychological and social outcomes (Phinney 2003; Umaña-Taylor 2004). Ethnic labeling is particularly important to understand in youth with Chinese ancestry because their ethnic background places them in the US minority, and because they remain understudied in both the ethnic identity literature as well as in the adolescent literature more broadly speaking (Levesque 2007; Sue et al. 1998). The goal of this study was to examine associations between the ethnic labels that young adults with Chinese ancestry use to identify themselves and key features of development, for instance, the ethnic diversity of individuals’ community and peer network, their strength of ethnic identity, language proficiency, and adjustment, including self-esteem and positive relationships with parents and peers.

Ethnic Labels in Young Adulthood

In the US, ethnic group membership often is primary and salient to those from ethnic minority backgrounds given that ethnicity represents a social category that has a wide range and long history of implications. Early in development, many grade school children have already acquired a savvy conceptualization of who they are, ethnically (Aboud 1987). This knowledge can be attributed to a natural motivation for children to categorize themselves (Rotheram and Phinney 1987), as well as to the practical necessity of completing school forms in which children often are required to label themselves demographically. On such forms, a standard label relevant to those with Chinese ancestry is represented by a broad category such as “Asian.” Yet, in reality, the possible labels available to Chinese youth are much more diverse.

For instance, a panethnic label (e.g., Asian) appears simple and all-encompassing, which is perhaps why it often is used in standard forms where generic labels are the norm. However, a deeper implication of identifying oneself as panethnic exists. Americans with Chinese ancestry who purposefully choose a panethnic Asian label may endorse a psychological commonality with diverse cultures that span areas of East, Southeast, and South Asia, as well as Pacific Island nations (Espiritu 1992). Panethnic identification also could illustrate an intentional alignment with a larger group for political or social reasons. Although the Chinese subgroup represents the biggest proportion of Asians in the US, Chinese Americans still remain a small minority within the larger society. Individuals thus may identify with and support a panethnic movement in order to strengthen their social power as a broad, Asian collective (Espiritu 1992; Kibria 2000). An alternative interpretation of panethnic identification is that these individuals may simply be unfamiliar with or unaware of the nuances of being specifically Chinese.

In contrast, to claim a heritage national identity (e.g., Chinese) acknowledges a precise aspect of one’s ethnic ancestry. A heritage national identification represents a close tie to one’s specific country of origin and implies an awareness of what it means to be uniquely Chinese (e.g., versus Japanese or Laotian). As another identity option, young adults could claim a nationally American identity and not acknowledge their ethnic heritage at all. These youth can be seen as being more connected with or assimilated to the mainstream culture or as actively disengaged with their heritage culture.

Additional labeling choices include pairing a panethnic or heritage national label with an American label. Those who choose a panethnic-American identity (e.g., Asian American) may align themselves with both the broader Asian culture as well as with the mainstream US culture, acknowledging not only their ethnic heritage but also their status as an American. Similarly, a heritage national-American label (e.g., Chinese American) implies a dual identification with one’s specific ethnic culture as well as with mainstream America. Both cases of hyphenated American identification can be seen as proxies for biculturalism, that is, identification with one’s ethnic as well as mainstream cultures (Berry 2003). Such bicultural identification can have a number of positive implications for development (LaFromboise et al. 1993).

Although ethnic identity research has typically focused on the quintessential quest for identity that is salient during adolescence, self-labeling processes are pivotal concerns within the developmental period of emerging adulthood, or between the ages of about 18–30 (Arnett 2000). During this period, young adults can legally vote and take a stand on the political and social issues that affect not only themselves, but also the world around them. For instance, the panethnic Asian movement has long been visible on college campuses, wherein Asian American students have panethnically banded together to increase their presence in taking a stand on political issues (e.g., anti-Vietnam War), protesting discrimination, and promoting their collective welfare and rights (Okamoto 2006). As another example of the relevance of ethnic labeling in emerging adulthood, young adults’ self-identification on government documents can affect demographic statistics and the federal funding allocated to specific subgroups. Patterns of self-identification thus appear particularly important to consider during the post-high school years and as adolescents mature into adults and become active members of their communities.

Contextual and Personal Correlates of Ethnic Labels

Given the qualitative differences among ethnic labels, as well as social implications of ethnic identification, it is vital to understand factors that may be related to ethnic label choice. Are there differences among those who choose a global and potentially political panethnic label, those who retain the specificity of their unique heritage, or those who biculturally acknowledge their ethnic heritage along with their American identity? A number of issues, such as generation, the ethnic diversity of one’s community and peer group, one’s strength of ethnic identity, and language proficiency, could relate to one’s choice of a particular ethnic label over another.

Generational Status

Prior research on ethnic labels has largely focused on group variation due to country of birth or generational status (Phinney 2003). A number of studies have found that second or third generation Latin American youth are more likely to report a panethnic or hyphenated American identity compared to their foreign-born counterparts (Buriel and Cardoza 1993; Zarate et al. 2005). Masuoka (2006) similarly found that foreign-born adults from Latin and Asian American backgrounds were most likely to use a national label alone. Country of birth or generation thus appears to provide validation for identifying as “Chinese” or “American.” That is, one who was actually born in America may feel more authentic in choosing an American identification compared to one who was not born in America. Although research on young adults with Chinese ancestry is scarce, those born in the US should be more likely to choose a panethnic-American or heritage national-American label compared to their foreign-born peers. Similarly, foreign-born youth should be more likely than youth from later generations to choose a heritage national label as a reflection of their country of origin.

Ethnic Diversity of Young Adults’ Community

From an ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner 1979), influences from within one’s immediate environment or microsystem are important to consider. The ethnic diversity of one’s surrounding community or environment is one example. In recent work, Asian Americans in ethnically isolated enclaves (e.g., Chinatown, Koreatown) reported little interaction with those from other ethnicities and, perhaps due to such same-ethnic immersion, tended to exhibit identities based on their heritage nation (Masuoka 2006). In less ethnically homogenous communities, young adults from Chinese backgrounds thus could be more motivated to panethnically unite with other Asians in the community, whether those community members are Chinese or not. Furthermore, within ethnically diverse communities, it may be more normative to claim a diverse ethnic identification (Qian 2004); hence, individuals may feel freer to use any combination of American, panethnic, or heritage national labels. Taken together, the ethnic diversity of young adults’ community is a key ecological variable that could be associated with young adults’ ethnic labeling choices.

Ethnic Diversity of Young Adults’ Peer Group

An ethnically diverse environment implies that there are options for youth to establish relationships with ethnically diverse community members. Although research has mostly focused on broad ethnic differences in friendship structures (Hamm et al. 2005; Way et al. 2001), the ethnic diversity of one’s friendships or peer group may be related to young adults’ choice of ethnic labels. From an acculturation perspective (Berry 2003), an individual with Chinese ancestry who reports a hyphenated American identity could reflect a bicultural orientation. Such comfort with both heritage and mainstream cultures could result in individuals having a mixture of Asian and European American friends. As another example, individuals those embody a segregated acculturation status may choose a heritage national label alone and feel so strongly connected to their ethnic group that they do not interact with different-ethnic peers.

Strength of Ethnic Identification

Personal characteristics, such as strength of ethnic identity, are also important to consider in terms of young adults’ choice of ethnic labels. From a social identity perspective (e.g., Tajfel 1981), a sense of attachment or connectedness to one’s social group is likely to lead to an awareness of a common or linked fate among group members (Lien et al. 2003). Based on this theoretical view, we might expect Chinese youth with a strong sense of ethnic identity to generalize their belief in a common fate to other Asian group members and to thus endorse a panethnic label. Alternatively, strong levels of ethnic identity could lead to the greater retention of a heritage national label depending on how one defines one’s ethnic group members (e.g., as specifically Chinese or as broadly Asian). In a sense, capturing and understanding the specific nature of one’s ethnic subgroup may require more “identity work” and therefore a strong sense of ethnic identity as compared to identifying with a general, panethnic default (Fuligni et al. under review). Indeed, Fuligni et al. (2005) found that ethnic identity, assessed via ethnic centrality or the importance placed on ethnic group membership, was higher in Asian and Latin American youth who chose national labels as compared to those who identified panethnically. To build on this area of work, links between ethnic labels and strength of ethnic identity were explored. Phinney’s (1992) conceptualization of ethnic identity was examined, which includes dimensions of ethnic affirmation and belonging, and ethnic identity achievement or exploration.

Language Use and Proficiency

Prior work has identified language proficiency as having a consistently strong relation with how individuals ethnically define themselves (Phinney et al. 2001). Based on such prior work, young adults fluent in their heritage language were expected to feel a stronger connection with their heritage culture and thus identify as nationally Chinese as opposed to panethnically Asian or hyphenated American. Opposite links were expected in terms of English proficiency.

Ethnic Labels and Social and Psychological Adjustment

Prior work on ethnic identity and adjustment has primarily focused on ethnic identity dimensions (e.g., ethnic affirmation or belonging, as described above) rather than ethnic labels. Such research has found that ethnic identity is related to adaptive adjustment outcomes and even buffers individuals from stressful experiences of ethnic discrimination or daily demands (Kiang et al. 2006; Wong et al. 2003). Ethnic identity also has been found to affect how individuals subsequently relate to others (Phinney 1992; Kibria 2000). Do ethnic labels have similar implications in terms of global self-esteem and socially-oriented variables, such as positive relationships with parents and peers?

Young adults choosing heritage national labels can be expected to report high self-esteem since prior work has found positive effects related to ethnic identity. Positive outcomes also have been linked to bicultural identification (Berry 2003; LaFromboise et al. 1993). In fact, those reporting hyphenated American labels may exhibit even higher self-esteem due to their dual identification. In light of relationships, young adults choosing heritage national or panethnic labels were expected to report positive relationships with parents and Asian peers. Due to their bicultural orientation, those choosing either of the two hyphenated American labels were expected to report positive relationships with parents, Asian, and European peers.

In examining ethnic labels and adjustment, it is important to consider the effect of ethnic labels in conjunction with the effect of ethnic identity. In particular, it is possible that ethnic identity, as traditionally defined through multidimensional scales, may trump any effects of ethnic label choice. For instance, Fuligni et al. (2005) found only modest associations between ethnic labels and academic outcomes compared to links between outcomes and strength of ethnic identity, as defined continuously. Hence, links between ethnic labels and adjustment were examined above and beyond the effect of more traditional measures of ethnic identity.

Notably, recent perspectives caution against assuming that ethnic identity is related to adjustment due to potential biases in the way that identity is measured (Cross and Fhagen-Smith 2001). Since ethnic identity often is assessed in an ethnic-central manner, results attesting to positive effects of ethnic identity may lead to a false assumption that ethnic identity (e.g., as opposed to bicultural or assimilated forms of identity) is important (Vandiver et al. 2001; Yip and Cross 2004). Examining ethnic labeling choices, as compared to dimensional measurements of ethnic identity, may circumvent this criticism in that the possible range of ethnic labels includes not only ethnic-centered concepts (e.g., heritage national or panethnic), but also less-ethnic centered identities (e.g., hyphenated American).

The Current Study

The primary goal of this research was to examine individual differences in ethnic label choice among young American adults from Chinese backgrounds. After examining the frequencies of ethnic labels, associations between labels and generation, the ethnic diversity of one’s community and peer group, ethnic identity, and language proficiency were considered.

Logistic regressions first determined whether contextual and personal variables predicted the likelihood of choosing specific ethnic labels. Based on prior research, the odds of choosing a heritage national label was expected to increase for foreign-born young adults, and for those who are proficient in their heritage language. The odds of choosing hyphenated American labels were expected to be greater for those who were US-born and proficient in the English language. In terms of the ethnic diversity of one’s community and peer group, less diversity was expected to increase the odds of identifying either panethnically or with a heritage national label. The strength of young adults’ ethnic identity was expected to predict the odds of ethnic label choice as well, though competing hypotheses preclude precise a priori expectations.

Average differences in contextual and personal variables also were examined among youth who chose different ethnic labels. Compared to young adults who chose panethnic or hypthenated American labels, those who chose a heritage national label were expected to be mostly foreign-born, to reside in less ethnically diverse communities, to have mostly Asians in their peer group, and to report more proficiency in their heritage language, but less proficiency with English. Differences in ethnic identity also were expected, but competing hypotheses preclude exact predictions. Age was included in both logistic regressions and analyses of variance, but was not expected to be significantly related to ethnic label choice.

Lastly, links between ethnic labels and adjustment were examined. Self-esteem was expected to be similarly high across all youth, but, perhaps due to their bicultural orientation, self-esteem was expected to be highest among those who chose hyphenated American labels. Young adults who chose heritage national or panethnic labels were expected to report positive relationships with parents and Asian peers, whereas those who chose hyphenated American labels were expected to report positive relationships across all three relational contexts. In addition, ethnic identity, as traditionally measured by ethnic affirmation and exploration, was expected to have an equal, if not stronger, effect on adjustment.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 259 young adults recruited primarily from college settings. Participants were required to be at least 18 years old and to have both parents with ancestry from China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan. Participants also were required to have been born in the US or to have resided in the US for at least 10 years. Given the current study’s interest in the period of young or emerging adulthood, participants were restricted to be between the ages of 18–32 (98.4% of the original sample). In addition, only those who provided an ethnic label to describe themselves were included in analyses. To ensure that the 5% of participants with missing ethnic labeling data did not significantly differ from those with complete data, a series of independent samples t-tests were conducted. No significant differences were found between participants who did and did not include a self-reported ethnic label on either demographic or key study variables.

Of the final sample of 242 young adults, approximately 40% reported mainland China as their family’s country of origin, 25% reported Taiwan, 6% reported Hong Kong, and the remaining 29% reported a combination of ethnic backgrounds (e.g., Hong Kong/China, Taiwan/China). Approximately 30% were first-generation immigrants, 64% were second-generation or born in the US, 5% were third generation, and 1% was fourth generation. Because of the small number of young adults from third and fourth generations, generational analyses focused primarily on country of birth (i.e., first generation versus second, third, and fourth generations grouped together). Males comprised 27% of the sample and females 73%. Average age was 23.97 years (SD = 4.13). Individuals were widely geographically distributed with 26% living in large Eastern cities, 14% in small Eastern cities, 22% in large Western cities, 13% in small Western cities, 17% in large Midwestern cities, and 8% in small Midwestern cities. The sample as a whole had high levels of education with 44% currently in college, 19% holding a college degree, 19% currently in graduate school, and 18% with a graduate degree.

Procedure

Internet technology was used to recruit participants and to administer questionnaires due to its ease and efficiency in accessing potential participants who reside in ethnically and geographically diverse areas of the US Data were collected using www.psychdata.net. Participants were recruited by sending basic information about the study to electronic distribution lists such as the Asian American Psychological Association and Division 45 (Society for the Psychological Study of Ethnic Minority Issues) of the American Psychological Association. Information also was sent to Chinese and Asian American student and professional groups. Professors of Psychology and Asian American Studies teaching at universities with large numbers of Chinese youth were contacted to request their help in notifying their Chinese students about the study. Snowball sampling likely accounted for a small portion of the data since participants were asked to notify other qualifying individuals about the study.

Participants were told that the goal of the study was to collect information regarding their attitudes, behaviors, and experiences about being Chinese American. Interested individuals were directed to a website where they consented by providing their e-mail address. Participants were then automatically linked to a different website from which they answered a series of self-report questionnaires. E-mail addresses were downloaded into a separate file from actual data; thus, identifying information was not linked with survey responses. Questionnaires took about 30 min to complete. As compensation, approximately 7% of participants were randomly selected to receive remuneration of $50 in the form of an electronic gift certificate. Although participants had the option of completing paper questionnaires, none made this request.

Measures

Ethnic Self-categorization

Original instructions from Phinney’s (1992) Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) were given which read, “In this country, people come from a lot of different cultures and there are many different words to describe the different backgrounds or ethnic groups that people come from. Some examples of the names of ethnic groups are Mexican American, Latino, Black, Asian American, American Indian, Anglo American, and Caucasian. Every person is born into an ethnic group, or sometimes to two or more groups, but people differ on how important their ethnicity is to them, how they feel about it, and how much their behavior is affected by it. These questions are about your ethnicity or ethnic group and how you feel and react to it.” Participants were then asked, “In terms of my ethnic group, I consider myself to be __________.” Open-ended responses were coded and categorized to represent heritage national (e.g., Chinese, Taiwanese, Chinese/Cantonese, 100% Made in China), panethnic (e.g., Asian), heritage national-American (e.g., Chinese American, Chinese–Taiwanese–American), and panethnic-American (e.g., Asian American) labels. Categorical placement was mutually exclusive. That is, individuals who reported, for instance, Asian American, were placed in the panethnic-American category only. The majority of participants reported labels that corresponded to these three categories. As discussed shortly, a small number reported a panethnic label alone (e.g., Asian), and one participant chose the label, “American”.

Ethnic Diversity of Community

The ethnic diversity of participants’ communities was assessed using a single item that asked, “What sort of environment or community do you live in now?” Reponses ranged from 1 not ethnically diverse at all to 4 very ethnically diverse.

Ethnic Diversity of Peer Network

To assess the ethnic diversity of participants’ peer group, participants read the following statement: “Some of the questions in this survey ask about your relationships with your Asian peers and Caucasian peers. Think about the friends you currently have and check the statement that best describes you.” There were three possible responses: 1 = I have mainly Caucasian or European American friends, 2 = I have a pretty good mix of Asian and Caucasian friends, 3 = I have mainly Asian and Asian American friends. Approximately 17% reported having primarily European American friends, 39% reported a mix of both, and 44% reported having primarily Asian and Asian American friends.

Language Proficiency

To assess heritage language proficiency, participants were asked to think about the language of their culture or ethnic group. They were then asked to respond on a four-point scale ranging from 1 not at all to 4 very much how much they use (i.e., speak, listen, read) the language. To assess English proficiency, participants were asked to think about the English language and responded to a similar question, also on a four-point scale, regarding how much they use (i.e., speak, listen, read) English.

Ethnic Identity

Ethnic identity was assessed using the MEIM (Phinney 1992). The Affirmation and Belonging subscale, consisting of five items, assesses ethnic belonging and pride. Sample items read, “I am happy I am a member of the ethnic group I belong to,” “I have a strong sense of belonging to my ethnic group,” and, “I have a lot of pride in my ethnic group and its accomplishments.” The Ethnic Identity Achievement subscale consists of seven items and measures individuals’ search and exploration of the history, traditions, and what it means to be a member of their ethnic group. Sample items read, “I have spent time trying to find out more about my ethnic group, such as its history, traditions, and customs,” “I have a clear sense of my ethnic background and what it means to me,” and, “I think a lot about how my life will be affected by my ethnic group membership.” Items are scored on a four-point scale ranging from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree with higher scores reflecting higher affirmation and exploration. Internal consistencies were high (Affirmation, α = .90; Exploration, α = .81).

Global Self-esteem

The four-item Global Self-Worth subscale from the Self-Perception Profile for College Students (Neemann and Harter 1986) and the four-item Mood/Affect subscale from the Dimensions of Depression Profile (Harter et al. 1988) were used as indicators of adjustment. Questions are written in a “structured alternative format,” designed to reduce socially desirable responses (Harter 1982). A sample self-worth item reads, “Some people like the kind of person they are BUT Other people wish they were different.” A sample mood/affect item reads, “Some people often feel depressed BUT Other people are usually cheerful.” Participants first decide whether they are more like the people described in the first or second part of the sentence and then decide whether that statement is Sort of True or Really True. Items are scored on a four-point scale. Internal consistencies were .83 for self-worth and .84 for depression. Consistent with prior work (Harter 1999), self-worth and mood/affect were highly correlated (r = .65, p < .001), and thus combined to represent a global index of self-esteem with higher scores indicating better adjustment. The internal consistency of all eight items was higher than alphas found for each scale separately, further supporting aggregation of scales (α = .89).

Positive Relationships

The Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI; Furman and Buhrmester 1985), a widely used measure of positive and negative dimensions of relationships, was used to assess relationships with parents, Asian peers, and European American peers. Focusing on positive aspects of relationships, each subscale (Companionship, Intimacy, Support, Admiration, Reliable Alliance) consists of three items rated on a five-point scale with higher scores reflecting more positive relationships. Sample items read, “How much do these people treat you like you’re admired and respected,” “How sure are you that these relationships will last in spite of fights,” and, “When you are feeling down or upset, how often do you depend on these people to cheer things up?” The internal consistencies of this overall measure (α = .89), as well as within each relationship (parents = .92, Asian peers = .95, European peers = .96), were good.

Results

Preliminary Analysis of Study Variables

Basic links between study variables were first investigated. As shown in Table 1, living in more ethnically diverse communities was correlated with higher self-esteem and more positive relationships with Asian peers. Subscales of ethnic identity were associated with each other and both dimensions were linked to greater heritage language proficiency, self-esteem, and more positive relationships with parents and Asian peers. Heritage language and English proficiencies were negatively correlated with each other. Greater proficiency in heritage language was associated with more positive relationships with Asian peers. Greater proficiency in English was associated with greater self-esteem. In terms of adjustment, self-esteem was positively associated with positive relationships across all three relational contexts.

Since generational status and the ethnic diversity of participants’ peer groups were measured categorically, independent samples t-tests and multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) were used to examine their associations with other study variables. T-tests revealed that young adults from the first generation were more proficient in their heritage language (t (228) = 2.87, p < .01), less proficient in English (t (228) = −2.04, p < .05) and had less positive relationships with Asian peers (t (208) = −2.31, p < .05) compared to their counterparts from later generations. MANOVA results suggested that the ethnic diversity of peer groups was associated with the ethnic diversity of communities, individuals’ ethnic identity, heritage language proficiency, and relationships with Asian and European peers (F range 3.11 −26.09, p < .05). Bonferroni post hoc tests revealed that those with mostly European American peers tended to live in less diverse communities, to report lower ethnic identity, lower heritage language proficiency, less positive relationships with Asian peers, and more positive relationships with European peers. Differences were largely between those with mostly Asian peers and those with mostly European peers, with those who reported a diverse mixture of friends falling somewhere in between. Lastly, a chi-square analysis examining links between generation and peer diversity revealed that these variables were not significantly associated with each other (χ² (2) = 1.78, ns).

Ethnic Labels in Young Adults from Chinese Backgrounds

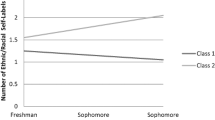

As shown in Fig. 1, participants primarily chose heritage national (22%), heritage national-American (35%), and panethnic-American (42%) labels. Of those who chose a heritage national label, the vast majority chose Chinese (75%; other labels included Taiwanese, Hong Kong, and Cantonese). Interestingly, only three participants chose a panethnic label alone, and only one participant chose an American label alone. These four participants were dropped from further analyses since the small cell sizes precluded meaningful comparisons. Notably, using chi-square analysis and an analysis of variance, respectively, label choice was not found to vary by gender (χ² (2) = .52, ns) or educational status (F (6, 238) = .99, ns).

Ethnic Labels and Contextual and Personal Variables

Logistics Regressions with Variables Predicting Label Choice

Multinomial logistic regressions examined whether young adults’ likelihood of choosing specific ethnic labels varied as a function of contextual and personal variables. Age, generational status (effects coded such that first generation or foreign-born youth = −1, youth from later generations = 1), ethnic diversity of young adults’ communities, ethnic diversity of their peer groups (dummy coded with those who reported an even mixture of Asian and European friends serving as the reference group), ethnic identity dimensions, and proficiency in heritage language and in English were the independent variables that predicted the odds of heritage national identification, heritage national-American identification, then panethnic-American identification. As shown in Table 2, the overall model was significant in predicting the odds of heritage national identification, (χ² (9) = 25.55, p < .01), but only generation and proficiency in English emerged as significant variables. Results suggested that, compared to those who were foreign-born, the odds for young adults from later generations to choose a heritage national label decreased by a ratio of .54. In addition, as young adults increased in English language proficiency, their odds of choosing a heritage national label decreased by a ratio of .34. Although the overall model predicting the odds of choosing a heritage national-American label was only marginally significant (χ² (9) = 16.23, p = .06), generational status emerged as a significant predictor (see Table 2). Specifically, compared to foreign-born young adults, the odds for those from later generations to choose a heritage national-American label increased by a factor of 1.52. Ethnic exploration also was marginally significant (p = .06) such that each unit increase in exploration was associated with a 1.89 increase in the odds that young adults would choose a heritage national-American label. Individual predictors and the overall model predicting the odds of choosing a panethnic-American label were not significant (χ² (9) = 10.03, ns) and, hence, not shown in Table 2.

Average Differences in Study Variables by Label Choice

A chi-square analysis was used to determine whether young adults who reported different ethnic labels varied in the ethnic diversity of their peer groups. Results indicated that these variables were not significantly related (χ² (4) = 4.26, ns). That is, there were no predictable associations between ethnic labels and whether youth had mostly Asian, European, or an ethnically diverse mixture of friends.

A MANOVA was used to examine remaining associations between choice of ethnic labels and contextual and personal variables. The independent variable in the model was label choice and the dependent variables included age, generational status (effects coded), the ethnic diversity of young adults’ communities, two indices of ethnic identity, and proficiency in heritage language and in English. As shown in Table 3, self-reported ethnic labels were significantly associated with generation (F (2, 222) = 9.80, p < .001). Bonferroni post hoc tests showed that young adults who reported a heritage national label were most likely to have been foreign-born or of the first generation. Those who reported heritage national-American or panethnic-American labels were most likely to have been born in the US Ethnic labels also were significantly associated with ethnic identity exploration (F (2, 222) = 3.17, p < .05) as well as with proficiency with the English language (F (2, 224) = 4.82, p < .01). Post hoc tests revealed that differences in ethnic exploration primarily fell between those who chose a heritage national-American label versus a panethnic-American label. Young adults choosing the former reported higher ethnic exploration compared to their panethnic-American counterparts. In terms of English proficiency, youth who chose heritage national labels were less proficient in English compared to those who chose either of the two hyphenated American labels. Ethnic labels were only marginally associated with heritage language proficiency, and were not associated with the ethnic diversity of respondents’ communities.

Associations Among Ethnic Labels, Ethnic Identity, and Adjustment

A second MANOVA examined how self-reported ethnic labels were related to adjustment. Labels were entered as the independent variable, and global self-esteem and positive relationships with parents, Asian peers, and European American peers were entered as dependent variables. As shown in Table 4, labels were significantly associated with self esteem (F (2, 201) = 4.01, p < .05) such that individuals who reported a heritage national-American label reported highest levels of self-esteem, particularly in comparison to those who reported a panethnic-American label. Ethnic labels also were associated with relationships with Asian peers (F (2, 201) = 6.43, p < .01) such that youth who reported a heritage national-American label reported more positive relationships with Asian peers compared to youth who reported either a heritage national label alone or a panethnic-American label.

To determine whether ethnic labels were significantly associated with outcomes above and beyond the effect of ethnic identity, follow-up analyses were conducted with ethnic identity affirmation and exploration included as covariates. With the addition of ethnic identity, the association between ethnic labels and self-esteem was no longer significant (F (2, 201) = 1.52, ns), whereas the effect of ethnic affirmation was (F (1, 201) = 5.78, p < .01). In terms of positive relationships with Asian peers, ethnic labels remained significant after taking ethnic identity into account (F (2, 201) = 5.78, p < .05). Ethnic exploration was significantly associated with relationships with Asian peers as well (F (1, 201) = 8.81, p < .01).

Discussion

Young American adults with Chinese ancestry are often faced with the decision of how to self-categorize themselves into ethnic categories. A number of possible labeling options exist, including the use of a broad, panethnic label, an ethnic label that is more specific to one’s heritage nationality, or either a panethnic or heritage national label along with the label, “American.” In fact, given such diversity in ethnic labeling options, findings from this study suggest that, when young adults were asked to open-endedly report what they consider their ethnicity or ethnic group to be, there was no clear majority in labeling preferences. Specifically, 22% reported a heritage national label alone, 35% reported a heritage national-American label, and 42% reported a panethnic-American label.

Notably, only a handful of young adults reported a panethnic label alone. Although the use of a panethnic label could be a conscious choice that is reflective of broader group solidarity or of social or political motives, panethnicity also could be a somewhat of a default choice that is unique to the US because of its simplicity and common representation in official documents, standardized testing forms, college applications, and the like. Identifying oneself as panethnically Asian thus could reflect a familiarity with the categories that are typically used by the US government and many other social institutions in this culture (Fuligni et al. under review). Young adults who are highly acculturated may well be familiar with such norms and may be expected to identify in a panethnic manner. However, individuals who are highly acculturated may choose instead to follow another US convention, namely, to pair a heritage national or panethnic label with the term, “American.” It appears, from our data, that when young adults do use a panethnic label they are much more likely to do so in conjunction with an American ending. Indeed, over 75% of young adults chose either a heritage national-American label or a panethnic-American label, which provides a glimpse into the levels of acculturation that these youth embody. Young adults choosing to recognize both their ethnic and mainstream identities could be seen as bicultural (Berry 2003); hence, both forms of hyphenated American labels could serve as proxies for bicultural identification.

Also notable was the fact that only one participant chose an American label alone, suggesting that the vast majority of young adults from Chinese backgrounds do identify with their ethnic backgrounds at some level. Young adults’ retention of their heritage identity and lack of identification as solely American could be, in part, attributable to the many obstacles and challenges that can be associated with full assimilation (Portes and Zhou 1993). For instance, prior work has found that individuals from Asian backgrounds are commonly perceived as perpetual “strangers” to the US and, because of their foreignness, are often targets of discrimination (Goto et al. 2002). Such a socially prescribed identity as a non-American could be difficult to overcome and, thus, these young adults may have difficulty with identifying as solely American. Another explanation for the low frequency of the use of an American-only label is that potential participants were told that the study focuses on the experiences of Chinese Americans. This criterion could have resulted in an underestimation of Chinese youth who identify as solely American because these youth could have decided not to participate in a “Chinese American” study. Hence, it would be interesting to examine, in future work, whether choice of ethnic labels varies as function of the framework in which these questions are assessed. Indeed, recent work by Harris and Sim (2002) suggests that the context in which adolescents are asked about their ethnic background (e.g., at school versus at home) can affect the way they ethnically categorize themselves.

Links Between Label Choice and Contextual Variables

Given that young adults reported a diverse range of ethnic labels, an important question to address is whether certain contextual and personal variables are associated with label choice. From an ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner 1979), important influences from within the microsystem, namely, the ethnic diversity of young adults’ communities and peer groups, were expected to play a role in ethnic labeling. Conceptually, differences in the ethnic composition of young adults’ immediate environment could result in different social norms or expectations that can determine how these youth define themselves. For instance, young adults who reside in ethnically isolated enclaves (e.g., Chinatown) and those who have mostly Asian friends could be expected to choose a heritage national label due to their same-ethnic immersion. Similarly, young adults who have ethnically diverse friends might be expected to identify themselves using hyphenated American labels. However, contrary to these expectations, neither community nor peer diversity emerged as significant predictors of the odds of choosing specific ethnic labels. Likewise, average differences in the ethnic diversity of young adults’ communities and peer groups did not vary among those who chose different ethnic labels.

One explanation for the lack of significance found could be due to measurement issues. In assessing community ethnic diversity, participants indicated the extent to which their communities are “ethnically diverse.” For those who indicated that their community is not very diverse, it remains unclear whether such perceived homogeneity was due to large numbers of ethnic minorities or to a predominant European American population. Certainly, an ethnically homogenous environment could have different effects on an individual based on whether he or she is a member of that homogenous group or rather a minority within the group. It is thus possible that the ethnic diversity of young adults’ communities is related to ethnic labeling, as hypothesized, but that any potential effects were negated due to our measurement that did not distinguish between homogenously ethnic minority and European communities.

Precise distinctions regarding the ethnic diversity of young adults’ peer groups also were unclear. Recall that participants were asked whether their friends are mostly European, mostly Asian, or an even mixture of both. Although this broad assessment does provide some useful information regarding young adults’ general friendship structures, more detailed inquiries may have been helpful. For instance, it would have been interesting to consider whether one’s friends are specifically Chinese, multiethnic, etc. Young adults who have mostly Chinese friends (versus Asian) could be more likely to identify as nationally Chinese compared to those who have a mixture of friends from diverse Asian cultures. These latter youth may be more likely to choose a panethnic label. Hence, to better understand the association between peer networks and ethnic labels, or lack thereof, it would be important for future research to more clearly define and assess the ethnic composition of individuals’ peer groups. It also would be interesting to determine whether differences exist between individuals’ ideal peer networks and the actual ethnic diversity of peers that are available to them in their environment. For instance, as described in our preliminary analyses, young adults who had mainly European American friends tended to reside in less diverse areas. Might there be differences among young adults who have mostly European peers as a result of a purposeful choice (e.g., in a diverse community) versus those who have mostly European peers because their neighborhood or school is primarily European? Indeed, peer relationships and contextual diversity have been found to interact in prior work (Cairns et al. 1998).

As an additional investigation into peer relationships and ethnic labeling, it would be interesting in future research to determine the concordance between adolescents’ ethnic labels and their friends’ ethnic labels. A large component of ethnic identity involves understanding what it means to be a member of one’s ethnic group (Phinney 1992). Perhaps same-ethnic friends share this ethnic understanding, or perhaps they utilize each other to explore and to learn more. In circumstances where one does report having many same-ethnic friends, it would be worthwhile to understand whether friends’ ethnic labels are related to one’s own.

Links Between Label Choice and Personal Variables

Beyond contextual variables, personal characteristics, such as generational status, ethnic identity, and language proficiency, were expected to be related to ethnic label choice. The strongest associations were found with generational status. Specifically, there were greater odds of choosing a heritage national label alone and lower odds of choosing a heritage national-American label for those who were foreign-born or of the first generation. Moreover, individual differences were found among the three ethnic labels such that those who reported a heritage national label alone were primarily foreign-born, and those who reported either a heritage national-American or panethnic-American label were mostly young adults from later generations. These findings are consistent with prior work with Latin American youth (Zarate et al. 2005), and suggests that generation may provide validation or authenticity that allows individuals to justify the terms that they use to describe themselves.

Although no associations were found between ethnic labels and ethnic affirmation or belonging, labeling choice was associated with ethnic identity exploration. Results revealed that young adults who reported greater levels of ethnic exploration were more likely to choose a heritage national-American label. Furthermore, those who identified themselves as heritage national-American reported significantly higher levels of ethnic search or exploration compared to their counterparts who chose panethnic-American labels. There appears, then, to be a deeper process involved with retaining a heritage national sense of identification, as opposed to a more general sense of being panethnically Asian. Collectively, these findings suggest that some degree of “identity work” needs to be done in order to retain one’s specific ethnic national identity (Fuligni et al. under review). Although differences in ethnic exploration among young adults who chose heritage national and heritage national-American labels were not significant, ethnic identity search or exploration seems particularly relevant to those who wish to define themselves as bicultural, that is, both heritage national and American. Drawing on Eriksonian ideas (1968), young adults who are balancing and reconciling their heritage national and American identities may be in more of an ethnic “crisis” and may be actively investigating what their ethnic group membership means in order to gain a deeper understanding of who they are.

Proficiency of the English language also was found to be significantly associated with young adults’ ethnic label choice. As expected, individuals who reported greater English proficiency had significantly lower odds of choosing a heritage national label alone. In terms of group differences, young adults who chose either of the two hyphenated American labels were significantly more proficient in English compared to those who reported a heritage national label alone. Perhaps mastering the English language provides a sense of justification for identifying oneself as partly American. Although young adults’ proficiency in their heritage language did not emerge as significant, patterns were reversed such that those who were proficient in their heritage language tended to report a heritage national or heritage-national American label. To build on these findings, one important direction is to determine whether certain dimensions of proficiency may be driving results. For instance, prior research on language acquisition (e.g., Feyton 1991; Krashen 1981) suggests that skills in listening comprehension may be particularly important in proficiency and in predicting developmental outcomes. Future work could attempt to disentangle these potentially different effects and determine whether listening, speaking, or reading/writing skills are most central to youth development.

Links Between Label Choice and Adjustment

Consistent with prior research that has documented positive effects of ethnic identity and of bicultural acculturation (e.g., Berry 2003; Kiang et al. 2006), the types of ethnic labels that young adults with Chinese ancestry use to identify themselves were expected to have important implications for global self-esteem and parent and peer relationships. Specifically, young adults who chose a heritage national-American label reported significantly higher self-esteem compared to those who chose a panethnic-American label. The positive nature of aligning oneself with one’s heritage national identity is generally consistent with prior work attesting to the positive benefits of ethnic identity (Phinney 2003), and even with some of the research attesting to the “immigrant paradox,” or the idea that immigrants fare just as well or even better than their second generation peers (McDonald and Kennedy 2004).

From a social identity perspective (e.g., Tajfel 1981), having some sense of affiliation with a social group is theoretically thought to contribute to positive outcomes. However, perhaps more attention should be placed on whether identification with certain social groups might have neutral or even negative effects on adjustment. For instance, our results suggest that identifying with a somewhat abstract group, such as a panethnic group, may not be as beneficial as identifying with a group that is more specific and couched within one’s precise ethnic ancestry.

In terms of parent and peer relationships, young adults who chose a heritage national-American label reported more positive relationships with Asian peers compared to those who reported a heritage national or panethnic-American label. From an acculturation perspective (Berry 2003), perhaps these individuals who identify with both their heritage national ancestry as well as with the mainstream American culture are truly bicultural, contributing to this positive effect. However, it remains unclear why the young adults who chose a heritage national identity did not exhibit similarly positive relationships with Asian peers, or why presumably bicultural youth with hyphenated American identities did not report more positive relationships with European peers. Indeed, label choice was not related to relationships with European peers or with parents at all. Again, further investigation into the specific characteristics and ethnic composition of young adults’ social and peer networks may shed needed light on this topic.

A key question to address in terms of ethnic labeling and outcomes is whether differences in adjustment among youth who chose different ethnic labels existed beyond the effect of ethnic identity, as traditionally defined by continuous dimensions of ethnic affiliation and exploration (Phinney 1992). In the present study, ethnic labels were no longer significantly associated with self-esteem after taking the strength of ethnic identity into account. Specifically, the effect of one’s ethnic affirmation and belonging appeared to trump the effect of ethnic labels. One explanation for this strong association between self-esteem and ethnic affirmation is that both constructs reflect affectively-based dimensions of the self. In terms of positive relationships with Asian peers, differences across ethnic labels remained significant above and beyond the effect of ethnic identity subscales. However, ethnic exploration emerged as an equally strong, if not stronger, predictor of relationships with Asian peers. Taken together, results are generally consistent with prior work by Fuligni et al. (2005) and suggests that, although ethnic labeling is associated with differences in several important outcomes, ethnic identity dimensions remain additionally important, if not more important, variables to consider in young adults’ development. In future work, additional dimensions of ethnic identity could be incorporated and compared to ethnic labeling effects. For instance, ethnic centrality, or the importance that one attributes to one’s ethnicity, has been put forth as a particularly important dimension to examine in development (Rowley et al. 1998). In fact, ethnic identification, as measured by ethnic labels or multidimensionally, may be more or less salient and influential in individuals’ lives depending on whether ethnicity is considered to be central to the self.

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations to this study should be noted. First, ethnic self-labeling was examined at only one point in time. The manner in which young American adults with Chinese ancestry potentially change their label choice over time would be an important issue to consider in future work. Since this was a largely correlational study, we also cannot definitively speak to the directionality of effects. Another limitation was that our sample was comprised primarily of females. Participants also tended to be highly educated, perhaps due to our Internet sampling methodology. Addition research in this area would need to incorporate more diverse samples in order to allow for more generalizable findings. It is also important to highlight that, although the present study focused on youth from Chinese backgrounds as a distinct Asian subgroup, there are a number of subethnicities within the Chinese culture itself that are diverse and deserving of further attention. Our participants most likely represented the ethnic Han Chinese culture, which constitutes the majority within mainland China, but over 50 additional ethnicities exist (People’s Republic of China 2005). Whether or not there are similarities or differences among such diverse subgroups from within the more specific Chinese ethnicity is still an empirical question.

A notable strength of this study was that we focused on young adults from Chinese backgrounds who have been traditionally understudied in the literature (Levesque 2007). Moreover, much of the existing research on ethnic labeling has tended to focus on younger adolescents (Zarate et al. 2005) or on adults (Masuoka 2006). Developmentally, as adolescents emerge into adulthood, pursue higher education, vote, enter the workforce, and start their own families, they have more of an opportunity and motivation to truly explore what their ethnicity means to them (e.g., through college student groups, professional organizations). Ethnic labeling may become particularly important during this post-adolescent period and continue to reflect a critical aspect of one’s overall identity and of how one relates to others.

Given the diverse situations that we encounter, especially as we mature and gain more experience outside of our immediate families and academic settings, it would be important to extend the current research and to determine whether ethnic label choice varies across different situational contexts. Emerging work suggests that individuals do report variation in identity as a function of social contexts or relationships (Harris and Sim 2002; Shelton and Sellers 2000). Indeed, youth from ethnic minority backgrounds may very well use different ethnic labels when interacting with different people, calling into question important implications regarding self-consistency and the development and formation of multiple selves (Harter 1999).

Conclusion

In summary, our results demonstrate that young American adults from Chinese backgrounds choose distinct ethnic labels that can reflect their specific national heritage, their national heritage in conjunction with an American affiliation, or an American affiliation along with a broader identification with their panethnic Asian heritage. Choice of ethnic labels was related to young adults’ country of birth, the degree to which they were exploring what it means to be a member of their ethnic group, and their proficiency in the English language. Ethnic labels were also related to self-esteem and positive relationships with Asian peers, with the most optimal outcomes reported by those who acknowledged their specific ethnic ancestry along with their American affiliation. Taken together, ethnic self-identification appears to have unique implications for development as well as for how individuals relate to the broader society. These and other processes associated with ethnic labeling are particularly important to understand during emerging adulthood and within a society, such as the US, where ethnic group membership is such a salient aspect of development.

References

Aboud, F. E. (1987). The development of ethnic self-identification attitudes. In J. S. Phinney & M. Rotheram (Eds.), Children’s ethnic socialization: Pluralism and development (pp. 32–55). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. B. Organista, & G. Marin (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 17–37). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Buriel, R., & Cardoza, D. (1993). Mexican American ethnic labeling: An intrafamilial and intergenerational analysis. In M. Bernal & G. Knight (Eds.), Ethnic identity (pp. 197–210). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Cairns, R., Xie, H., & Leung, M. (1998). The popularity of friendship and the neglect of social networks: Toward a new balance. In W. M. Bukowski & A. H. Cillessen (Eds.), Sociometry then and now: Building on six decades of measuring children’s experiences with the peer group. New directions for child development (pp. 5–24). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cross, W. E., & Fhagen-Smith, P. (2001). Patterns of African American identity development: A life span perspective. In C. L. Wijeysinghe & B. W. Jackson (Eds.), New perspectives on racial identity development: A theoretical and practical anthology (pp. 243–270). New York: New York University Press.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Espiritu, Y. (1992). Asian American panethnicity: Bridging institutions and identities. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Feyton, C. M. (1991). The power of listening ability: An overlooked dimension in language acquisition. Modern Language Journal, 75, 173–180.

Fuligni, A. J., Witkow, M., & Garcia, C. (2005). Ethnic identity and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 41, 799–811.

Fuligni, A. J., Witkow, M., Kiang, L., Baldelomar, O. A. Stability and change in ethnic labeling among adolescents from Asian and Latin American immigrant families, (under review).

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024.

Goto, S. G., Gee, G. C., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2002). Strangers still? The experience of discrimination among Chinese Americans. Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 211–224.

Hamm, J. V., Brown, B. B., & Heck, D. J. (2005). Bridging the ethnic divide: Student and school characteristics in African American, Asian American, European American, and Latino adolescents’ cross-ethnic friend nomination. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15, 21–46.

Harris, D. R., & Sim, J. J. (2002). Who is multiracial? Assessing the complexity of lived race. American Sociological Review, 67, 614–627.

Harter, S. (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87–97.

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self. New York: Guilford.

Harter, S., Nowakowski, M., & Marold, D.B. (1988). The dimensions of depression profile. Unpublished manual, University of Denver, CO.

Kiang, L., Yip, T., Gonzales-Backen, M., Witkow, M., & Fuligni, A. J. (2006). Ethnic identity and the daily psychological well-being of adolescents from Mexican and Chinese backgrounds. Child Development, 77, 1338–1350.

Kibria, N. (2000). Race, ethnic options, and ethnic binds: Identity negotiations of second-generational Chinese and Korean Americans. Sociological Perspectives, 43, 77–95.

Krashen, S. D. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

LaFromboise, T., Coleman, H. L., & Gerton, J. (1993). Psychological impact of biculturalism: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 395–412.

Levesque, R. J. R. (2007). The ethnicity of adolescent research. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 375–389.

Lien, P., Conway, M. M., & Wong, J. (2003). The contours and sources of ethnic identity choices among Asian Americans. Social Science Quarterly, 84, 461–481.

Masuoka, N. (2006). Together they become one: Examining the predictors of panethnic group consciousness among Asian Americans and Latinos. Social Science Quarterly, 87, 993–1011.

McDonald, J. T., & Kennedy, S. (2004). Insights into the ‘healthy immigrant effect’: Health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Social Science Medicine, 59, 1613–1627.

Neemann, J., & Harter, S. (1986). The Self-perception profile for college students. Unpublished manual, University of Denver, CO.

Okamoto, D. G. (2006). Institutional panethnicity: Boundary formation in Asian–American organizing. Social Forces, 85, 1–25.

People’s Republic of China (2005). Regional autonomy for ethnic minorities in China. Retrieved July 31, 2007, from http://english.gov.cn/official/2005–07/28/content_18127.htm

Phinney, J. S. (1992). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adoelscent Research, 7, 156–176.

Phinney, J. S. (2003). Ethnic identity and acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. B. Organista, & G. Marin (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 63–81). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Phinney, J. S., Romero, I., Nava, M., & Huang, D. (2001). The role of language, parents and peers in ethnic identity among adolescents in immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 30, 135–153.

Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 530, 74–96.

Qian, Z. (2004). Options: Racial/ethnic identification of children of intermarried couples. Social Science Quarterly, 85, 746–766.

Rotheram, M, & Phinney, J. S. (1987). Introduction: Definitions and perspectives in the study of children’s ethnic socialization. In J. S. Phinney & M. Rotheram (Eds.), Children’s ethnic socialization: Pluralism and development (pp. 10–28). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Rowley, S. J., Sellers, R. M., Chavous, T. M., & Smith, M. A. (1998). The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 715–724.

Shelton, J. N., & Sellers, R. M. (2000). Situational stability and variability in African American racial identity. Journal of Black Psychology, 26, 27–50.

Sue, D., Mak, W. S., & Sue, D. W. (1998). Ethnic identity. In L. C. Lee & W. S. Zane (Eds.), Handbook of Asian American psychology (pp. 289–323). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories: Studies in social psychology. Cambridge: Cambridge Univesity Press.

Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2004). Ethnic identity and self-esteem: Examining the role of social context. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 139–146.

Vandiver, B. J., Fhagen-Smith, P. E., Cokley, K. O., Cross, W. E., & Worrell, F. C. (2001). Cross nigrescence model: From theory to scale to theory. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 29, 174–200.

Way, N., Cowal, K., Gingold, R., Pahl, K., & Bissessar, N. (2001). Friendship patterns among African American, Asian American, and Latino adolescents from low-income families. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18, 29–53.

Wong, C. A., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. (2003). The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality, 71, 1197–1232.

Yip, T., & Cross, W. E. (2004). A daily diary study of mental health and community involvement outcomes for three Chinese American social identities. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10, 394–408.

Zarate, M. E., Bhimji, F., & Reese, L. (2005). Ethnic identity and academic achievement among Latino/a Adolescents. Journal of Latinos and Education, 4, 95–114.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Wendy Kiang-Spray for her comments on an earlier draft.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kiang, L. Ethnic Self-labeling in Young American Adults from Chinese Backgrounds. J Youth Adolescence 37, 97–111 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9219-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9219-x