Abstract

This study evaluated how culture relates to parenting and children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms, and whether there are cultural differences in how maternal parenting style relates to children’s adjustment among three cultural contexts: Romanian, Russian, and French. The sample included 325 children, aged 9–11 years, from Romania (n = 123), Russia (n = 112), and France (n = 90). Children completed questionnaires regarding their perceptions of maternal parenting style, and their life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. French children reported lower levels of authoritative parenting style and higher levels of authoritarian parenting style compared to their Romanian and Russian peers. Further, French children reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than both their Romanian and Russian peers, while Russian children had higher life satisfaction than their Romanian and French peers. The strengths of the associations between parenting style and both children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms, however, did not differ based on children’s cultural context. Our findings suggest the importance of cultural context in relation to parenting styles and children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. Further, our study shows that the relations between parenting and children’s adjustment are similar across the cultural contexts included in this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Children’s life satisfaction and depression are key aspects of children’s emotional development (Milevsky et al. 2007; Suldo and Huebner 2004). Life satisfaction has been associated with children’s health-related quality of life, prosocial behavior, and academic achievement (see Lyubomirsky et al. 2005 for a review). Depressive symptoms are the most common emotional symptoms experienced by children and adolescents, and have negative consequences for their social and school functioning as well as for their mental health (see Collishaw 2009 for a review). Given the impact of both life satisfaction and depressive symptoms on children’s development and maladjustment, it is important to deepen our understanding of factors, such as parenting style, related to them. Further, cultural context shapes parenting style and children’s life satisfaction and depression (see Diener et al. 2009 for review), however, few studies investigated the relations among these constructs. One purpose of this study is to evaluate how culture relates to parenting and children’s life satisfaction and depression. Another purpose is to investigate whether there are cultural differences in how parenting style relates to children’s life satisfaction and depression among three cultural contexts, Romanian, Russian, and French, respectively.

2 Culture and Parenting Style

Parenting style refers to a constellation of parenting behaviors conducive to a persistent emotional climate in a broad range of contexts and situations (Coplan et al. 2002; Darling and Steinberg 1993). Baumrind’s (1971, 1978) conceptualization of parenting style is widely employed in explaining individual differences in parenting practices (see Parke and Buriel 2006 for a review). According to Baumrind, the parenting styles vary along two dimensions—parental acceptance/responsiveness and demandingness/control. Parental responsiveness refers to the degree of parental nurturance, warmth, and positive reinforcement in response to children’s emotional and psychological needs. Parental demandingness refers to behavioral control over the child’s actions, and the use of authority and disciplinary practices.

Previous literature has shown that these dimensions reflect three parenting styles in Western countries, particularly the United States and Australia: authoritative (high on both dimensions), authoritarian (high demandingness, low responsiveness), and permissive (low demandingness, high responsiveness; Baumrind 1971, 1978, 2013; see Sorkhabi 2005 for a review).

Fewer studies, however, evaluated parenting styles cross-culturally and included non-Western samples (Sorkhabi 2005). It is also important to note that most studies on non-Western samples relied on Asian samples and yielded mixed findings, when children reported on their parents’ parenting styles. Specifically, some studies showed that adolescents from Western countries, such as Canada and the United States, report higher authoritative parenting, while adolescents from Asian countries, such as India, report higher authoritarian parenting (Garg et al. 2005; Jambunathan and Counselman 2002; Maccoby and Martin 1983). Other studies showed the opposite (Rudy and Grusec 2006) or reported non-significant differences on children’s perceptions of authoritative parenting (Porter et al. 2005). Few studies explored cultural differences on permissive parenting, and showed that Asian college students, compared to those from Western countries, perceive their parents as relying more on this parenting style (Barnhart et al. 2013).

Previous studies conducted on Eastern European samples evaluated parenting strategies such as love/hostility, and autonomy/control, or involvement, and reported that children who perceive higher levels of parental acceptance or involvement, and lower levels of control are more likely to experience higher life satisfaction and lower depressive symptoms (Gherasim et al. 2013; Robila and Krishnakumar 2006). To our knowledge, very few studies investigated Baumrind’s parenting styles in Eastern Europe. Grigorenko and Sternberg (2000) demonstrated that Russian children perceive their parents as more authoritative and neglectful, and less authoritarian and indulgent. Another study showed that indulgent (high responsiveness, low strictness) and democratic (high responsiveness, moderate strictness) parenting styles rather than authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles are positively associated with adolescents’ psychological adjustment across several Russian regions (Glendinning 2015). No previous studies, however, compared Baumbrid’s parenting styles among samples from Eastern Europe, or between samples from Eastern versus Western Europe.

To advance the literature, we evaluated whether there are differences in children’s perceptions of parenting style among three cultural contexts: Romanian, Russian, and French. Parenting interpreted through children’s perceptual lenses is likely to be different from parents’ self-reported rearing practices (Steinberg 2001). We relied on children’s perceptions of maternal rearing practices because recent research emphasizes the importance of children’s own experiences as “receivers” of parenting (e.g., Jonsson and Ostberg 2010; Morris et al. 2013) and because the effects of parenting style might depend on how children interpret parental behaviors (Morris et al. 2013). For example, previous studies showed that children who perceive their parents as displaying negative parenting strategies are at increased risk for negative outcomes (Morris et al. 2013). Further, previous literature suggests that although the experience of authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles has universal significance for children’s adjustment, the meaning and consequences of parenting styles may vary depending on how they are perceived in specific cultural contexts (e.g., Barnhart et al. 2013; Garg et al. 2005). Therefore, it is important that studies rely on children’s perceptions of parenting styles, especially in cross cultural studies (Güngör and Bornstein 2010).

Parents’ long-term socialization goals shape parenting practices and might explain why a specific parenting style is used more in one cultural context than in others (e.g., Keller and Otto 2009; see Sorkhabi 2005 for a review). Specifically, Western cultures, including France, endorse children’s autonomy and self-expression as socialization goals, which are consistent with authoritative parenting. In turn, this parenting style promotes a range of positive outcomes in children, such as autonomy, emotional regulation, and fewer social problems (e.g., Barnhart et al. 2013; Baumrind et al. 2010; Ishak et al. 2012; Querido et al. 2002; Rinaldi and Howe 2012). In contrast, non-Western countries such as Romania and Russia are thought to share interdependence as a socialization goal specific to more collectivistic cultures, and traditionally, obedience toward adults in power, including parents, rather than self-expression are valued (Güngör and Bornstein 2010; Inglehart and Klingemann 2000). In addition, it is important to note that the former communist societies, including Romania and Russia, have experienced economical, psychological, and social changes during the transition from communism to a free market economy. In turn, these changes have been accompanied by distress, which likely influenced families’ well-being and approach to raising children (Robila and Krishnakumar 2006), and increased the likelihood of relying on less effective parenting styles. Thus, we expected that there would be differences in children’s perceptions of parenting style between French children and those from both Romania and Russia, but not between perceptions of Romanian and Russian children. Specifically, we hypothesized that children from France would report higher authoritative parenting but lower authoritarian parenting compared to both their Romanian and Russian peers.

3 Culture, Life Satisfaction, and Depressive Symptoms

Studies that explored the relation between culture and life satisfaction or depression comparing various national groups are relatively rare (Barnhart et al. 2013). Young adults (i.e., college students) from Western countries, such as the United States, France or the United Kingdom, report higher levels of positive affect, optimism, and life satisfaction than do those from African, Asian, and South American countries (Cheung et al. 2011; Church et al. 2014). Similarly, the only cross-cultural study evaluating life satisfaction based on a sample of adolescents showed that non-Western (Korean) adolescents reported lower life satisfaction than their Western peers (Park and Huebner 2005). Regarding the relation between culture and depression specifically, studies have demonstrated that young adults (i.e., college students) from Western countries score lower on depression, and Asian young adults tend to score higher (Iwata and Buka 2002; Okazaki and Kallivayalil 2002). Surprisingly, no study evaluated cross-cultural differences in children’s levels of depressive symptoms.

A distinct set of studies focused on investigating differences in life satisfaction between European countries. These studies showed that adults from South European countries, such as France or Spain, experience lower levels of life satisfaction than one might expect based on their growth of per capita gross domestic product (GDP), compared to North European countries, such as England or the Netherlands (see Diener et al. 2009 for a review). Few studies, however, evaluated whether there are differences in life satisfaction between individuals from Western countries and those from countries with a history of communism (e.g., Russia and Eastern European countries). The findings consistently showed that adults from Russia and the former communist states of Eastern Europe, such as Romania, had lower levels of life satisfaction compared to other nations with less wealth, but without a history of communism, such as Latin American countries (see Inglehart and Klingemann 2000; Tov and Diener 2009 for reviews). Further, adults’ life satisfaction decreased more after the collapse of the communism (Balatsky and Diener 1993; Oishi and Schimmack 2010; Oishi et al. 2009; Veenhoven 2001). Explanations proposed in the literature for differences in levels of life satisfaction between Western and Eastern European countries include historical factors, political instability, economic decline, and psychological difficulties of the latter (Chirkov et al. 2003; Inglehart and Klingemann 2000).

Overall, relatively little is known regarding cross-cultural differences in children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms, particularly between children from Western and Eastern European countries. Thus, we extended the literature by evaluating whether there are differences in life satisfaction and depressive symptoms among children from France and two former communist countries, Romania and Russia. We expected that children from France would report higher life satisfaction and lower depressive symptoms than both their Romanian and Russian peers. Further, we did not expect differences in the levels of life satisfaction or depressive symptoms between Romanian and Russian children, given their similar societal experiences.

4 Parenting Style and Children’s Life Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms

Previous literature has shown that each parenting style is associated with distinct outcomes in children. Specifically, studies on Western samples, such as the United States, Canada and Finland, indicated that the authoritative parenting style has been associated with lower levels of psychological and behavioral dysfunction, better social skills, and academic success (Baumrind et al. 2010; Chan and Koo 2011; Lamborn et al. 1991). The authoritarian parenting style has been linked with social difficulties, delinquent behavior, and low achievement in childhood (Rinaldi and Howe 2012) and adolescence (Chan and Koo 2011). Further, the permissive parenting style has been associated with more behavior problems, and increased anxiety, but better social skills in childhood (Lamborn et al. 1991; Milevsky et al. 2007; Rinaldi and Howe 2012). Studies based on Asian children and adolescents revealed similar results (e.g., Ishak et al. 2012; see Sorkhabi 2005 for a review).

In spite of progress in identifying consequences of Baumrind’s parenting style, the associations between parenting styles and children’s life satisfaction or depressive symptoms received less attention in the literature. Most previous studies evaluated these relations in Western countries and showed that children who perceive their parents as authoritative report higher life satisfaction (Chan and Koo 2011; Lamborn et al. 1991; Milevsky et al. 2007; Pace and Shafer 2015; Suldo and Huebner 2004). Studies conducted on non-Western cultures are relatively rare, limited to a few cultural contexts (e.g., China and Croatia), and suggest that the authoritative and permissive styles have a similar positive impact on children’s life satisfaction (e.g., Raboteg-Saric and Sakic 2013; see Sorkhabi 2005 for a review).

Regarding the relation between parenting and depression specifically, previous literature has focused primarily on evaluating the relations between parenting practices, measured as parental warmth or control, and depressive symptoms (see McLeod et al. 2007 for a review), with little attention to the association between Baumrind’s parenting styles and children’s depressive symptoms (see Yap et al. 2014 for a review). Findings suggest that authoritative parenting is related to low levels of depressive symptoms, while authoritarian parenting is related to higher levels of depression in children and adolescents from Western cultures (see Yap et al. 2014 for a review). Although scarce, the literature suggests that greater permissive style predicts higher levels of childhood depressive symptoms (Rinaldi and Howe 2012).

In addition, previous literature (Sorkhabi 2005; Yap et al. 2014) suggests that context specificity may influence the relations between parenting styles and children’s adjustment. In this study, we investigated the relations between parenting styles and both children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms and whether these relations differ based on the cultural context. Consistent with the context specificity hypothesis (Yap et al. 2014), we expected that these relations would be different between France and both Romania and Russia, but not between Romania and Russia, given their history of communism and dramatic societal transformations after the change of regimes.

5 Method

5.1 Participants

The sample included 325 children (178 girls) enrolled in urban public schools in France (n = 90, 50 girls), Romania (n = 123, 63 girls), and Russia (n = 112, 65 girls). Children from France were recruited from an urban area in the South region; the Romanian children were recruited from a city in the North-Eastern region, while the children from Russia were recruited from the Moscow metropolitan area. Invitation letters describing the study were distributed to families through schools, and families agreed their children to volunteer for the study. Children’s mean age was 10.07 years. Descriptive characteristics of the samples are presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference in gender distribution across samples, all χ2s < 2.20, ps > .05. There were age differences among subsamples, F(2, 322) = 11.76, p < .01; Romanian children were older than their Russian and French counterparts.

5.2 Procedure

As part of a larger study, children completed questionnaires assessing their perceptions of maternal parenting style, and their life satisfaction and depressive symptoms in the second semester of the school year. Permission for the study was obtained from the school authorities and principals, and parents signed consent forms prior to the children’s participation.

5.3 Measures

The parenting style and life satisfaction measures were translated from English to Romanian, Russian, and French using the back-translation method. The depressive symptoms measure was translated from French to Romanian and Russian using the same method. The back-translation method retained the conceptual meaning of the original measures.

5.3.1 Parenting Style

An adapted version of the 38-item version of Primary Caregivers Practices Report (PCPR; Robinson et al. 1995) was used to assess children’s perceptions of their mothers’ parenting styles. In the original version of the questionnaire, parents reported their own parenting style. In this study, the items were adapted to measure the children’s perceptions of maternal behavior on authoritative (18 items; e.g., I talk with my mother about my troubles), authoritarian (10 items; e.g., My mother demands me to do things), and permissive (10 items; e.g., My mother spoils me) parenting styles. Children rated their mothers’ behavior on a 4-point scale (1 = almost never and 4 = almost always), and items were averaged so that a continuous variable was obtained. Exploratory factor analysis, using the Varimax rotation, yielded a clear three-factor solution, with loadings ranging from .30 to .77, which accounted for 34.93 % of the total variance: Authoritative Style (accounting for 17.20 % of the variance), Authoritarian Style (accounting for 11.33 % of the variance), and Permissive Style (accounting for 6.40 % of the variance). The factor structure was similar to the structure found by Robinson et al. (1995), except for one item from the authoritative and two items from the permissive subscales, which were eliminated because of the low correlation with these scales. For each cultural group, the EFA indicated the same three-factor solution, and the factors accounted for 32.23–41.77 % of the total variance. All items had medium to high loadings, with absolute values ranging from .32 to .77 for each cultural group. Considering the similarity in the component structure, the factor analyses supported the assumption that the scales measured the same constructs among all groups.

Studies showed that the PCPR has good reliability and validity (Porter et al. 2005; Rinaldi and Howe 2012) in that it is associated with children’s psychological adjustment, such as anxiety, happiness, and self-esteem (Pereira et al. 2014; Raboteg-Saric and Sakic 2013). In this study, alphas for the entire sample were .86, .78, and .48 for the authoritative, authoritarian and permissive scales, respectively. Alphas for each cultural group ranged from .78 to .90 for the authoritative style, from .69 to .81 for the authoritarian style, and from .29 to .58 for the permissive style. Based on low internal consistency of the permissive style scale, we did not include this scale in subsequent analyses. These results are consistent with previous studies indicating that two parenting styles, authoritative and authoritarian, are invariant across cultures, while the permissive parenting style is not adequately represented in non-Western countries (Porter et al. 2005).

5.3.2 Children’s Life Satisfaction

Children’s life satisfaction was measured with the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS; Huebner 1994). The 31-item questionnaire consists of four subscales assessing children’s life satisfaction in four different domains: family (seven items, e.g., I enjoy being at home with my family), friends (nine items, e.g., My friends treat me well), school (eight items, e.g., I look forward to going to school), and self (seven items, e.g., I like myself). Participants responded to each item using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = never to 4 = always. Two items from the school dimension and one item from the self dimension were eliminated because of the low inter-correlations with the total scores. Exploratory factor analysis indicated a four-factor solution for the entire sample, which accounted for 43.33 % of the total variance, with the subscales accounting for 9.01–12.90 % of the variance. EFA indicated four factors accounting for 40.44–49.89 % of the total variance for each sample. All items had high loadings, with absolute values ranging from .32 to .67 in the Romanian sample, from .37 to .84 in the Russian sample and from .32 to .79 in the French sample.

Consistent with the previous literature, the four subscales (family, friends, school, and self) were significantly associated (rs range between .16 and .42, all ps < .01). A total life-satisfaction score was computed by summing the responses across items. Alpha for the entire sample was .77 (alpha for the Romanian sample = .79, alpha for the Russian sample = .85, and alpha for the French sample = .79). Alphas for MSLSS subscales range from .65 to .81. Previous studies showed that MSLSS has good psychometric properties in that it is associated with well-being and psychopathology (Raboteg-Saric and Sakic 2013; Tam et al. 2012).

5.3.3 Children’s Depressive Symptoms

Children’s depressive symptoms were measured with Moor and Mack’s (1982) version of the Children Depression Inventory (Kovacs and Beck 1977). The scale is designed so that children are presented with 26 sets of three responses. The three response options are scored 0, 1, or 2. The total score was computed by summing the items scores. The scale has demonstrated good test—retest reliability and consistent associations with other scales measuring childhood depression (Doerfler et al. 1988; Finch et al. 1987). In this study, the internal consistency was .73 for the entire sample, and .71 .79, and .65 for the Romanian, Russian, and French samples, respectively.

6 Results

We conducted preliminary analyses to investigate whether child gender, child age, family socioeconomic status (SES, low, medium, and high), or family status (intact vs. not intact families) were related to children’s perceptions of parenting and their life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. Next, we presented associations among the main study variables. Then, we evaluated whether there are cultural differences in children’s perceptions of parenting style and their life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. Finally, we examined associations between parenting style and children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms, and whether there are cultural differences in the relations between parenting style and children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. For each analysis, we first discuss the results based on the entire sample, followed by results based on each cultural group.

6.1 Preliminary Analyses

There were no significant differences in perceived maternal parenting style and children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms based on child’s gender. Zero-order associations showed that children’s age was related to children’s life satisfaction based on the entire sample, r = −.13, p = .01. Age was not significantly related to life satisfaction when analyses were performed separately on each sample, rs ranged between .03 and .12, all ps > .05. An ANOVA analysis indicated the children from families with high levels of SES reported higher scores on authoritative parenting than those from families with medium levels of SES, F(2, 309) = 3.48, p = .03, M = 3.37, SD = .40 and M = 3.22, SD = .46. Follow-up analyses on each cultural group showed that family SES has no significant effect on authoritative parenting when analyses were performed separately on each sample, Fs ranged between .87 and 2.32, all ps > .05. In addition, children with intact families compared to those with non-intact families (divorced, separated, or deceased parents), reported lower levels of depressive symptoms, t(323) = 2.22, p = .02, M = 9.82, SD = 5.56 and M = 11.51, SD = 6.09. Follow-up analyses on each sample from each cultural group, showed that this result was significant only for the Romanian sample, t(121) = 2.52, p = .01, M = 9.25, SD = 5.24 and M = 12.93, SD = 6.69 for children from intact and non-intact families. Because of these significant results, we repeated the main analyses controlling for the relevant demographic variable (age, family SES or family status). Because none of the results changed significantly, for ease of reading, we report the analyses without controlling for these demographic variables.

Regarding associations between the parenting variables, zero-order correlations showed that, based on the entire sample, children who reported higher levels of authoritative maternal parenting style also reported lower levels of authoritarian parenting style (see Table 2). When analyses were conducted for each cultural group separately, the associations were significant for both Romanian and Russian samples, but they were non-significant for the French sample (see Table 3).

Further, children who reported higher levels of depressive symptoms also reported lower levels of life satisfaction based on the entire sample, and based on each subsample (see Tables 2, 3), confirming that life satisfaction and depressive symptoms are markers of adjustment (e.g., Suldo and Huebner 2004).

6.2 Cultural Differences in Children’s Perception of Parenting Style

ANOVA analyses showed that there were main effects of the cultural group on children’s perceived parenting style, F(2, 322) = 6.90 for authoritative, and F(2, 322) = 16.90 for authoritarian parenting style, all ps < .01. As shown in Table 3, French children reported lower levels of authoritative parenting style compared to Romanian children. In addition, they reported higher levels of authoritarian parenting style compared to their Romanian and Russian peers.

6.3 Cultural Differences in Children’s Life Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms

We found main effects of the cultural groups on children’s adjustment, F(2, 322) = 17.22 for life satisfaction, and F(2, 322) = 4.42 for depressive symptoms, all ps < .01. Specifically, Russian children had higher life satisfaction scores than did their Romanian and French peers. In addition, French children reported higher levels of depressive symptoms than did their Romanian and Russian counterparts. No other differences were significant.

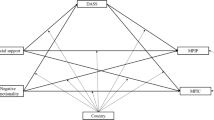

6.4 Associations Between Parenting Style and Children’s Life Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms

Table 2 presents the zero-order correlations between children’s perceived maternal parenting style and their life satisfaction and depressive symptoms on the entire sample. Associations were generally modest to moderate in magnitude, ranging between -.26 and .25, and showed that children who reported a more authoritative parenting style had higher life satisfaction and lower depressive symptoms. Further, children perceiving their mothers as relying on a more authoritarian parenting style reported lower life satisfaction and higher levels of depressive symptoms. When patterns of associations were examined for each cultural group, overall, the results were similar (see Table 3). In each sample, the authoritative parenting style was positively associated with life satisfaction and negatively associated with depressive symptoms. Authoritarian parenting style was negatively associated with life satisfaction in both Romanian and Russian samples, and it was positively associated with children’s depressive symptoms only in the Romanian sample.

To examine how much variance in children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms is explained by the parenting style, we conducted two regression analyses based on the entire sample with authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles as independent variables and life satisfaction (regression 1) and depressive symptoms (regression 2) as dependent variables. The parenting style dimensions explained a small, but significant variance in children’s life satisfaction (ΔR 2 = .06, F(2, 322) = 11.58, p < .001) and depressive symptoms, (ΔR 2 = .07, F(2, 322) = 14.03, p < .001).

6.5 Cultural Differences in the Relations Between Parenting Style and Children’s Life Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms

Next, we evaluated whether there are cultural differences in the associations of children’s perceived maternal parenting style with their life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. The patterns of correlations presented in Table 2 were not significantly different for Romanian, Russian, and French children (all Zs < 1.96, ps > .05).

7 Discussion

The first goal of our study was to examine how culture relates to parenting and children’s life satisfaction and depression. Specifically, we expected that French children would report higher authoritative parenting and lower authoritarian parenting compared to both their Romanian and Russian peers. We also expected that French children would report greater life satisfaction and lower levels of depressive symptoms compared to their Romanian and Russian counterparts. The second goal was to investigate the relations between parenting style and children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms and whether these relations differ as a function of culture. We expected that these relations would be different between France and both Romanian and Russia, but not between Romania and Russia.

Overall, our study adds to the literature by taking a cross-cultural approach, and reveals cultural differences in children’s perceptions of parenting styles. Specifically, we found that French (Western) children perceive their parents as using the authoritative parenting style less than do their Romanian counterparts, and the authoritarian parenting style more than do their non-Western (Romanian and Russian) peers. These unexpected results are inconsistent with the previous literature indicating that Western children and adolescents, compared to their non-Western peers, describe the authoritative parenting style as more representative and the authoritarian parenting style as less representative of their parents (Garg et al. 2005; Jambunathan and Counselman 2002; Porter et al. 2005). However, these results are in line with some findings reported in cross-cultural studies indicating that a high percentage of Western adults and children chose the authoritarian parenting style as more reflective of their own parents than do non-Western participants (Barnhart et al. 2013; Rudy and Grusec 2006). These results are also consistent with two studies showing that Russian children perceive their parents as more authoritative and less authoritarian (Glendinning 2015; Grigorenko and Sternberg 2000). An explanation of our findings may be related to the processes of modernization in Eastern Europe. Specifically, increased access to Western media and culture is likely to influence the parenting style and perceptions of effective parenting, such as increased autonomy granting and independence (Barnhart et al. 2013). Thus, newer cohorts of children in Eastern Europe may report more favorable parenting behaviors.

As expected, there were no differences in Russian and Romanian children’s perceptions of maternal parenting styles. One explanation is that parents in these countries may have a similar set of socialization goals grown out of the transition from communism to democracy. There is a possibility that democracy as a relatively new concept in former communist countries and exposure to democratic values may translate into similar perceptions of parenting that encourages more open communication and responsiveness to children’s needs. Further, as observers of their parents’ behavior, children may have similar perceptions of parenting if raised in similar societal environments. In addition, some studies suggest that in former communist countries, including Romania and Russia, there is a tendency toward changes in socialization goals, with more emphasis on individual differences and encouragement of independent thinking and acting (Ispa 2002; Wejnert and Djumabaeva 2005). These recent changes may be reflected in the similarity of children’s perceptions of parenting style.

Compared to the plethora of research on the life satisfaction of adults, only one comparative study has been conducted with children (Park and Huebner 2005). Overall, our results showed that Russian children experience better adjustment than Romanian or French children. Specifically, Russian children reported greater life satisfaction than their Romanian and French peers. Regarding children’s depressive symptoms, French children reported higher level of depressive symptoms than both Romanian and Russian counterparts.

Taken together, these results are in contradiction with previous research showing that adults from Western countries experience higher levels of life satisfaction than those from former communist countries, including Russia, and that Russian adults endorse lower levels of life satisfaction compared to former communist countries, including Romania (Balatsky and Diener 1993; Oishi et al. 2009; Oishi and Schimmack 2010; Veenhoven 2001). Our findings also question the notion that individuals from Western countries experience less depressive symptoms (Iwata and Buka 2002). However, the results complement previous findings indicating that French adults have the tendency to experience lower life satisfaction than one might expect based on their GDP per person compared to other European participants (see Diener et al. 2009 for a review). Because most previous studies have explored the cultural differences in life satisfaction and depression on samples of adults, more studies are needed to deepen our understanding of how culture is related to these constructs. Further, future studies should disentangle the role of the cultural context in children’s life satisfaction and depression in countries with similar historical events. Studies should also consider factors that may further explain differences in life satisfaction or depression across cultures. For example, the quality of interpersonal relationships has been identified as a key factor for the development of depression in particular (Hammen et al. 2014). Investigating whether children from all three cultural contexts experience relationship disturbances or positive social exchanges will increase our understanding of how cultural context and children’s life satisfaction or depression are related.

In addition, our study enhances the literature by evaluating the relations between parenting style and children’s life satisfaction and depression and whether these relations vary based on culture. Whereas most studies examined how parenting styles are associated with children’s behavior problems (Baumrind et al. 2010; Chan and Koo 2011; Rinaldi and Howe 2012), our study focused explicitly on children’s life satisfaction and depression. Our results showed that children who perceive their mothers as more authoritative also report higher life satisfaction and lower levels of depressive symptoms. Further, across all cultural groups, children who perceived their parents as more authoritarian reported lower levels of life satisfaction and higher levels of depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with the few previous studies conducted on samples of children or adolescents, mostly from Western countries, showing that authoritative parenting style is associated with greater life satisfaction and lower levels of depressive symptoms, whereas the authoritarian parenting style is associated with lower life satisfaction and higher levels of depressive symptoms (Milevsky et al. 2007; Pace and Shafer 2015; Raboteg-Saric and Sakic 2013; Rinaldi and Howe 2012; Suldo and Huebner 2004). Importantly, the parenting styles explained a small but significant variance in children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. In addition, our study adds to the literature by showing that the relations of parenting style with children’s life satisfaction and depression do not vary based on the cultural context. This is a novel finding that suggests that the relations between these constructs are similar across cultures.

Although this study enhances the literature, several limitations should be noted. First, our study relied on smaller samples compared to other previous comparative studies conducted on children and adolescents (e.g., Barnhart et al. 2013; Güngör and Bornstein 2010; Park and Huebner 2005). In addition, some measures yielded low internal consistency values (e.g., depression, the Romanian sample). Thus, these findings should be considered preliminary. Second, our results are correlational and do not lend themselves to any causal interpretations. Using a longitudinal design would allow to disentangle possible bidirectional effects. For example, it is likely that children showing healthy development may trigger parenting behaviors consistent with the authoritative style. Third, we obtained children’s reports of maternal parenting styles. Studies showed that in spite of similarities, there are some differences between mothers’ and fathers’ approaches to parenting (Brand and Klimes-Dugan 2010), and this work could be extended by incorporating assessments of paternal parenting styles. Finally, while obtaining children’s perspectives of their mothers’ parenting practices provides highly valuable information, future studies should rely on a multiple informant approach and observational methods that capture the mutual interactions that are central to parent–child relationships (Rinaldi and Howe 2012). Additional research including informant (e.g., parents, teachers, peers) reports will enhance the current findings.

Despite these limitations, the current findings advance the cross-cultural literature on children’s perceived parenting styles and their life satisfaction and depressive symptoms. In summary, we found that children from Romania and Russia perceive their mothers as using a less authoritarian and more authoritative parenting style compared to children from France. Our findings also show that the perceived parenting experience is important to consider in relation to children’s adjustment. Overall, our results suggest that the relations between parenting and children’s life satisfaction and depressive symptoms are similar and important across cultural contexts.

References

Balatsky, G., & Diener, E. (1993). Subjective well-being among Russian students. Social Indicators Research, 28(3), 225–243. doi:10.1007/BF01079019.

Barnhart, C. M., Raval, V. V., Jansari, A., & Raval, P. H. (2013). Perceptions of parenting style among college students in India and the United States. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 684–693. doi:10.1007/s10826-012-9621-1.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Development Psychology Monograph, 4(1, part 2), 1–103. doi:10.1037/h0030372.

Baumrind, D. (1978). Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence in children. Youth and Society, 9, 239–276.

Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative parenting revisited: History and current status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. S. Morris, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 11–34). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Baumrind, D., Larzelere, R. E., & Owens, E. B. (2010). Effects of preschool parents’ power assertive patterns and practices on adolescent development. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(3), 157–201. doi:10.1080/15295190903290790.

Brand, A. E., & Klimes-Dugan, B. (2010). Emotion socialization in adolescence: The roles of mothers and fathers. In A. Kennedy Root & S. Denham (Eds.), The role of gender in the socialization of emotion: Key concepts and critical issues. New directions for child and adolescent development (Vol. 128, pp. 85–100). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. doi:10.1002/cd.270.

Chan, T. W., & Koo, A. (2011). Parenting style and youth outcomes in the UK. European Sociological Review, 27(3), 385–399. doi:10.1093/esr/jcq013.

Cheung, C., Jose, P. E., Sheldon, K. M., Singelis, T. M., Cheung, M. W., Tiliouine, H., & Sims, C. (2011). Sociocultural differences in self-construal and subjective well-being: A test of four cultural models. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(5), 832–855. doi:10.1177/0022022110381117.

Chirkov, V., Ryan, R. M., Kim, Y., & Kaplan, U. (2003). Differentiating autonomy from individualism and independence: A self-determination theory perspective on internalization of cultural orientations and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 97. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.97.

Church, A. T., Katigbak, M. S., Ibanez-Reyes, J., de Jesus Vargas-Flores, J., Curtis, G. J., Tanaka-Matsumi, J., & Simon, J. Y. R. (2014). Relating self-concept consistency to hedonic and eudaimonic well-being in eight cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(5), 695–712. doi:10.1177/0022022114527347.

Collishaw, S. (2009). Trends in adolescent depression: a review of the evidence. In W. Yule (Ed.), Depression in childhood and adolescence: The way forward (pp. 7–18). London: Association of Child and Adolescent Mental Health.

Coplan, R. J., Hastings, P. D., Lagace-Seguin, D. G., & Moulton, C. E. (2002). Authoritative and authoritarian mothers’ parenting goals, attributions, and emotions across different childrearing contexts. Parenting: Science and Practice, 2, 1–26. doi:10.1207/S15327922PAR0201_1.

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113(3), 487–496. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487.

Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (2009). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. In E. Diener (Ed.), Culture and well-being: The collected works Ed Diener, social indicators research series (Vol. 38, pp. 43–70). Dorddrech: Springer.

Doerfler, L. A., Felner, R. D., Rowlison, R. T., Raley, P. A., & Evans, E. (1988). Depression in children and adolescents: a comparative analysis of the utility and construct validity of two assessment measures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(5), 769–772. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.56.5.769.

Finch, A. J, Jr., Saylor, C. F., Edwards, G. L., & McIntosh, J. A. (1987). Children’s depression inventory: Reliability over repeated administrations. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 16(4), 339–341. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp1604_7.

Garg, R., Levin, E., Urajnik, D., & Kauppi, C. (2005). Parenting style and academic achievement for East Indian and Canadian adolescents. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 36, 653–661.

Gherasim, L. R., Butnaru, S., Gavreliuc, A., & Iacob, L. M. (2013). Optimistic attributional style and parental behaviour in the educational framework: A cross-cultural perspective. In H. H. Knoop & A. Delle Fave (Eds.), Well-Being and cultures: Perspectives from positive psychology, cross-cultural advancements in positive psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 195–217). Dorddrech: Springer.

Glendinning, A. (2015). Parenting and adolescent adjustment in Asian–Russian cultural contexts: How different is it from the West? Rangsit Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 2(1), 33–48.

Grigorenko, E. L., & Sternberg, R. J. (2000). Elucidating the etiology and nature of beliefs about parenting styles. Developmental Science, 3(1), 93–112.

Güngör, D., & Bornstein, M. H. (2010). Culture-general and-specific associations of attachment avoidance and anxiety with perceived parental warmth and psychological control among Turk and Belgian adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 33(5), 593–602. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.005.

Hammen, C. L., Rudolph, K. D., & Abaied, J. L. (2014). Child and adolescent depression. In E. J. Mash & R. A. Barkley (Eds.), Child psychopathology (3rd ed., pp. 225–263). NewYork: The Guildford Press.

Huebner, E. S. (1994). Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment, 6, 149–158. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.149.

Inglehart, R., & Klingemann, H. D. (2000). Genes, culture, democracy, and happiness. In Ed Diener & Eunkook M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 165–183). Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

Ishak, Z., Low, S. F., & Lau, P. L. (2012). Parenting style as a moderator for students’ academic achievement. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 21(4), 487–493. doi:10.1007/s10956-011-9340-1.

Ispa, J. M. (2002). Russian child care goals and values: From perestroika to 2001. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17(3), 393–413. doi:10.1016/S0885-2006(02)00171-0.

Iwata, N., & Buka, S. (2002). Race/ethnicity and depressive symptoms: A cross-cultural/ethnic comparison among university students in East Asia, North and South America. Social Science and Medicine, 55(12), 2243–2252. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00003-5.

Jambunathan, S., & Counselman, K. (2002). Parenting attitudes of Asian Indian mothers living in the United States and in India. Early Child Development & Care, 172(6), 657–662. doi:10.1080/03004430215102.

Jonsson, J. O., & Ostberg, V. (2010). Studying young people’s level of living: The Swedish child-LNU. Child Indicators Research, 3(1), 47–64. doi:10.1007/s12187-009-9060-8.

Keller, H., & Otto, H. (2009). The cultural socialization of emotion regulation during infancy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(6), 996–1011. doi:10.1177/0022022109348576.

Kovacs, M., & Beck, A. T. (1977). An empirical-clinical approach toward a definition of childhood depression. In J. D. Schultirbrand & A. Rasken (Eds.), Depression in childhood: Diagnosis, treatment, and conceptual models (pp. 1–25). New York: Raven Press.

Lamborn, S. D., Mounts, N. S., Steinberg, L., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development, 62(5), 1049–1065. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In E. M. Hetherington (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 1–101)., Socialization, personality, and social development New York: Wiley.

McLeod, B. D., Weisz, J. R., & Wood, J. J. (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(8), 986–1003. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001.

Milevsky, A., Schlechter, M., Netter, S., & Keehn, D. (2007). Maternal and paternal parenting styles in adolescents: Associations with self-esteem, depression and life-satisfaction. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16(1), 39–47. doi:10.1007/s10826-006-9066-5.

Moor, L., & Mack, V. (1982). Versions françaises d’échelles d’évaluation de la dépression. I – Échelles de Birleson et de Poznanski (CDRS-R). Neuropsychiatrie de l’Enfance, 30, 623–626.

Morris, A. S., Cui, L., & Steinberg, L. (2013). Parenting research and themes: What have we learned and where to go next. In R. E. Larzelere, A. S. Morris, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 35–58). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Oishi, S., Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Suh, E. M. (2009). Cross-cultural variations in predictors of life satisfaction: Perspectives from needs and values. In E. Diener (Ed.), Culture and well-being. The collected works of social indicators research series (pp. 109–127). Dorddrech: Springer. doi:10.1177/01461672992511006.

Oishi, S., & Schimmack, U. (2010). Culture and well-being a new inquiry into the psychological wealth of nations. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(4), 463–471. doi:10.1177/1745691610375561.

Okazaki, S., & Kallivayalil, D. (2002). Cultural norms and subjective disability as predictors of symptom reports among Asian Americans and White Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 482–491. doi:10.1177/0022022102033005004.

Pace, G. T., & Shafer, K. (2015). Parenting and depression differences across parental roles. Journal of Family Issues, 36(8), 1001–1021. doi:10.1177/0192513X13506705.

Park, N., & Huebner, E. S. (2005). A cross-cultural study of the levels and correlates of life satisfaction among adolescents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 444–456. doi:10.1177/0022022105275961.

Parke, R. D., & Buriel, R. (2006). Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (Vol. 3, pp. 429–504). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Pereira, A. I., Barros, L., Mendonça, D., & Muris, P. (2014). The relationships among parental anxiety, parenting, and children’s anxiety: The mediating effects of children’s cognitive vulnerabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(2), 399–409. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9767-5.

Porter, C. L., Hart, C. H., Yang, C., Robinson, C. C., Olsen, S. F., Zeng, Q., et al. (2005). A comparative study of child temperament and parenting in Beijing, China and the western United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(6), 541–551. doi:10.1177/01650250500147402.

Querido, J. G., Warner, T. D., & Eyberg, S. M. (2002). Parenting styles and child behavior in African American families of preschool children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31(2), 272–277. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_12.

Raboteg-Saric, Z., & Sakic, M. (2013). Relations of parenting styles and friendship quality to self-esteem, life satisfaction and happiness in adolescents. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9(3), 749–765. doi:10.1007/s11482-013-9268-0.

Rinaldi, C. M., & Howe, N. (2012). Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and associations with toddlers’ externalizing, internalizing, and adaptive behaviors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(2), 266–273. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.08.001.

Robila, M., & Krishnakumar, A. (2006). Economic pressure and children’s psychological functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(4), 433–441. doi:10.1007/s10826-006-9053-x.

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77(3), 819–830. doi:10.2466/pr0.1995.77.3.819.

Rudy, D., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist groups: Associations with maternal emotion and cognition and children’s self-esteem. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(1), 68–78. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.68.

Sorkhabi, N. (2005). Applicability of Baumrind’s parent typology to collective cultures: analysis of cultural explanations of parent socialization effects. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(6), 552–563. doi:10.1177/01650250500172640.

Steinberg, L. (2001). We know some things: Parent–adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 11(1), 1–19.

Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2004). Does life satisfaction moderate the effects of stressful life events on psychopathological behavior during adolescence? School Psychology Quarterly, 19(2), 93–105. doi:10.1521/scpq.19.2.93.33313.

Tam, K. P., Lau, H. P. B., & Jiang, D. (2012). Culture and subjective well-being a dynamic constructivist view. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(1), 23–31. doi:10.1177/0022022110388568.

Tov, W., & Diener, E. (2009). Culture and subjective well-being. In E. Diener (Ed.), Culture and well-being: The collected works of social indicators research series (Vol. 38, pp. 43–70). Dorddrech: Springer.

Veenhoven, R. (2001). Are the Russians as unhappy as they say they are? Journal of Happiness Studies, 2(2), 111–136. doi:10.1023/A:1011587828593.

Wejnert, B., & Djumabaeva, A. (2005). From patriarchy to egalitarianism: Parenting roles in democratizing Poland and Kyrgyzstan. Marriage & Family Review, 36(3–4), 147–171. doi:10.1300/J002v36n03_08.

Yap, M. B. H., Pilkington, P. D., Ryan, S. M., & Jorm, A. F. (2014). Parental factors associated with depression and anxiety in young people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 156, 8–23. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gherasim, L.R., Brumariu, L.E. & Alim, C.L. Parenting Style and Children’s Life Satisfaction and Depressive Symptoms: Preliminary Findings from Romania, France, and Russia. J Happiness Stud 18, 1013–1028 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9754-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9754-9