Abstract

Although a growing body of psychological literature has examined the influence of culture on parenting style, relatively less attention has been paid to gender differences in parenting style across cultures. The present study examined perceptions of parenting style as a function of participant’s culture, participant’s gender, and parent gender in college students in India and the United States. Using a new vignette-based self-report measure that characterizes each of Baumrind’s three parenting styles, participants rated perceptions of effectiveness, helpfulness, caring, and normativeness of each style. Contrary to expectation, results showed that Indian college students considered the parent demonstrating permissive parenting to be more effective and helpful than US college students. In contrast, US college students considered the parents demonstrating authoritative and authoritarian parenting to be more effective, helpful, and caring than Indian college students. A majority of Indian and US college students selected the parent demonstrating authoritative parenting as most similar to their own parents, and the type of parent they wish to be in the future. Females considered the parent demonstrating authoritative parenting to be more effective and helpful than males. Relatively few effects of parent gender were found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Darling and Steinberg (1993) defined parenting style as “a constellation of attitudes toward the child that are communicated to the child and that, taken together, create an emotional climate in which the parent’s behaviors are expressed” (p. 488). Popularized by Diana Baumrind’s work, parenting style, its implications for child development, and the demographic factors by which it varies (e.g., culture, gender) have all been extensively studied in developmental and family science. Literature regarding parenting styles in European American samples has examined the role of both parent and child gender, specifically investigating whether mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles differ for sons and daughters. Cross-cultural research has emerged that primarily compares parenting styles of mothers in Eastern and Western cultures. Relatively rare are studies of parenting style that have incorporated the examination of culture, parent gender, and child gender. Parents across cultures have different socialization goals for boys and girls, which likely influence their parenting styles (Chao 2000). Thus, using hypothetical vignettes, the present study compared male and female college students’ perceptions of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles in India and the United States.

Culture and Parenting Style

In her seminal work, Baumrind (1966) first identified three parenting styles based on observations of mother–child interactions: authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive. Baumrind (1971) later amended the styles and created a typology based on the dimensions of parental control and warmth. Parental control is defined as behavioral control over the child’s actions, often through authority and discipline, whereas warmth is defined as nurturance and responsiveness to the child’s emotional and psychological needs. According to Baumrind (1971), authoritarian parents set and enforce rules with no parent–child negotiation, remaining high in control over the child’s behavior and often lower in warmth than the other two parenting styles. In contrast, authoritative parents discuss rules and their rationale, encouraging autonomy as well as adherence to rules, being high in control and also high in warmth and responsiveness towards the child. Permissive parents have little emphasis on rules and structure, being low in control and usually high in warmth. Sorkhabi (2005) reviewed many previous studies conducted predominantly with participants in the United States and China, concluding that Baumrind’s typology is applicable across these cultures. While parents in different cultures may endorse different styles of parenting more frequently, Sorkhabi (2005) stated that all three parenting styles are found in both collective and individualistic cultures.

Parents across cultures have unique socialization goals, such as helping their child become an autonomous, self-reliant individual or a socially interdependent individual (Keller and Otto 2009). The socialization goals shape parents’ everyday interactions and parenting styles with their children. Parents in Western cultures endorse autonomous socialization goals that focus on helping their children become independent, competitive, and self-expressive, while parents in Asian cultures emphasize obedience, respect, and social interdependence (Keller and Otto 2009). Authoritative parenting style places a high emphasis on development of autonomy in children, and is consistent with the socialization goals of Western parents. In contrast, authoritarian parenting that focuses on obedience and respect is consistent with the socialization goals of many Asian parents. Not surprisingly, Chao (2000) found that Chinese immigrant mothers reported using authoritarian parenting slightly more than European American mothers. Similarly, Jambunathan and Counselman (2002) found that mothers in India were more likely to report using authoritarian parenting and corporate punishment, while Indian immigrant mothers in the United States were most likely to report authoritative parenting. Even when children were asked to report on their mothers’ parenting styles, similar patterns were found. For instance, adolescents of European background in Canada were most likely to report authoritative parenting, while adolescents in India were more likely to report higher incidences of authoritarian parenting than the Canadian adolescents (Garg et al. 2005). Specifically in India, authoritarian parenting is also consistent with Hindu values of respect for and duty towards one’s parents (Saraswathi and Pai 1997).

Depending on parents’ long-term socialization goals, a given parenting style may be adaptive for child well-being in one cultural context, while maladaptive in another. Research with European American families has suggested authoritative parenting as the optimal parenting style, promoting autonomy and independence, competent social skills, higher academic achievement, fewer instances of substance abuse or other related behaviors, and better emotion regulation (Baumrind 1966, 1971; Darling and Steinberg 1993; Lamborn et al. 1991; Maccoby and Martin 1983). In contrast, authoritarian parenting is linked with maladaptive child outcomes in European American middle-class families. Interestingly, findings concerning parenting style and child outcomes in Asian families are mixed. Leung et al. (1998) found that authoritarian parenting was linked with higher academic achievement in Chinese children, while authoritative parenting was not correlated with academic outcomes in Chinese children. Rudy and Grusec (2006) showed authoritarian parenting to be associated with adequate self-esteem in their South Asian and Middle-Eastern immigrant sample in Canada. In contrast, other researchers have suggested that authoritarian parenting may be linked with lower self-esteem and lower life-satisfaction in Asian children (Shek 1999). These contradictory findings indicate the need to closely examine the constructs of authoritarian and authoritative parenting style, and how they are measured across studies. The present study did not include an assessment of youth outcomes, and instead focused on the ways in which different parenting styles were perceived by youth.

Parenting Style Across Parent and Child Gender in European American Families

Consistent with parents’ differing goals for girls and boys, parenting styles have also been shown to differ across the gender of the child. Research in Western cultures has shown that parents report using authoritarian parenting with boys, while authoritative parenting with girls. In a meta-analysis of the literature on differential socialization of boys and girls, Lytton and Romney (1991) reported that North American boys were treated with more restrictiveness and harsher punishment, characteristic of the authoritarian style, while North American girls were treated with more warmth, characteristic of the authoritative style.

Different parenting styles across the gender of the parent have also been suggested in the literature regarding Western populations. European American mothers have been more likely to endorse authoritative parenting, while fathers have been more likely to rate themselves higher in both authoritarian and permissive styles of parenting (Russell and Aloa 1998; Winsler et al. 2005). Conrade and Ho (2001) found that overall mothers were viewed by their college-aged children to be more authoritative and also more permissive than fathers.

The interaction of child and parent gender in influencing parenting style has been also examined. Conrade and Ho (2001) found that college-aged females perceived their mothers to be more authoritative than males did, who were more likely to perceive mothers as permissive. Males also were more likely than females to view their fathers as authoritarian. This study adds to both the findings on differential socialization of sons and daughters as discussed earlier and to the findings on differential socialization likely practiced by mothers and fathers.

Parenting Style Across Parent and Child Gender in Asian Families

Research on the role of gender in parenting in Asian cultures is quite limited. Someya et al. (2000) studied Japanese siblings, reporting that sons felt more parental rejection, indicative of the low levels of warmth seen in authoritarian parenting than daughters, who felt more parental warmth, which is indicative of authoritative parenting. The findings are similar to Lytton and Romney’s (1991) meta-analysis of North American studies, indicating that the authoritarian style may be used with boys more than girls across cultures.

With respect to parent gender, traditional gender roles in Asian cultures such as India encourage mothers to be nurturing caregivers, while fathers have traditionally been encouraged to have little involvement in childrearing (Rothbaum and Trommsdorff 2007). However, contemporary research suggests that middle-class fathers in urban areas of India are increasingly becoming more nurturing, affectionate, and interactive in the daily lives of their young children, suggesting a cultural shift in parenting approaches for fathers (Roopnarine et al. 1990). Strict adherence to gender roles might explain mothers being viewed as more authoritative and sometimes more permissive, while fathers are traditionally viewed as authoritarian when involved. This pattern is similar to the findings seen in Western cultures, however, research examining culture and parent gender together in influencing parenting style in Asia has thus far been limited.

Measurement Issues in Parenting Style Research Across Cultures

Although the initial studies of parenting style conducted by Baumrind (1966, 1971) were observational, much of the subsequent research has utilized parent and child reports of parenting style. The Child Rearing Practices Report (Block 1981), the Parental Authority Questionnaire (Buri 1991), and the Warmth and Involvement Scale (Robinson et al. 1995) are examples of scales that measure implicit perceptions of parenting styles. The present study focused on the explicit perceptions of parenting style, making it clear that attitudes about parenting style are being measured, not necessarily how one was parented. Measurement of such explicit perceptions is beneficial in cross-cultural studies because these perceptions likely represent culturally-shared notions about parenting, and provide an opportunity to examine perceptions concerning normativeness of various parenting styles in different cultural communities.

It is also important to distinguish between parent and child perceptions of parenting. Children may perceive or experience parenting styles differently than how the parents perceive actually parenting them. Smetana (1995) reported that European American middle-class children in the US perceived their parents as more authoritarian and permissive than parents perceived themselves to be, while the parents considered their styles of parenting to be more authoritative than their children reported. These findings illustrate that children may not experience parenting in the same manner parents believe their children will experience it. Children’s perceptions may be more relevant to their well-being, thus, it is important to focus specifically on children’s perceptions of parenting styles. This study focused specifically on college-aged children, who are considered to be in a developmental stage of emerging adulthood, the stage between adolescence and adulthood with a range of ages from approximately 18–25 in industrialized societies where entry into adult roles is delayed (Arnett 2000). Many Eastern cultures may not have a period of time between adolescence and adulthood. However, young people of urban areas in developing countries like India are more likely to experience a stage of emerging adulthood given some similarities to Western cultures in the form of delayed marriage and parenthood, particularly alongside the desire to obtain higher education (Arnett 2000).

A review of cross-cultural studies of parenting style also raises questions about the internal consistency of conventional parent- and child- report measures of parenting style. In particular, Chao (2000) used Buri’s (1991) Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ) with Chinese and European American mothers, reporting reliabilities between .49 and .71. Using the PAQ as well, Natarajan et al. (2010) reported relatively low Cronbach’s alpha values for their Indian college student sample (e.g., ranging from .47 to .67). These low values indicate that perhaps these measures lack the ability to accurately capture the constructs of parenting style. These low internal consistencies may be due to the application of measures that were created for use with Western samples to Eastern cultures, however, some of the measure have demonstrated low internal consistency even within Western cultural groups (e.g., see Chao 2000).

Regardless of measurement approach, the majority of the cross-cultural research on parenting has exclusively focused on East Asian samples with few studies focusing on South Asia. Moreover, little research has combined culture, child gender, and parent gender in regards to parenting styles specifically. Poole et al. (1982) focused on all three of these aspects in a study regarding socialization goals associated with parenting (i.e., autonomy). However, this study did not measure parenting styles as a construct.

The Present Study

The aim of the current study was to fill gaps and expand the existing literature on parenting style regarding culture and gender. Focusing on college students from India and the United States (US), the present study utilized a new assessment tool for measuring parenting styles. This measure included hypothetical vignettes representative of each of Baumrind’s three parenting styles, followed by questions concerning how each of the parenting style was perceived. The goal was to examine whether college students’ perceptions of parenting style differ as a function of their culture, their own gender, and the gender of the parent portrayed in hypothetical vignettes presented to them. College students reported on their perceptions of effectiveness, harmfulness or helpfulness, and level of caring demonstrated by each style. Further, perceptions of normativeness were assessed by asking about the parenting style most representative of the student’s own parent, the parenting style most common in their home community, and the parenting style the student would most like to employ in the future.

Group differences in perceptions of parenting styles across culture, student gender, and parent gender were expected. Overall, it was expected that Indian college students would perceive authoritarian parenting as more effective, helpful, and caring than US students, while US students would perceive authoritative parenting as more effective, helpful, and caring than Indian students. Male college students were expected to perceive authoritarian parenting as more effective, helpful, and caring than female college students, who were expected to perceive authoritative parenting as more effective, helpful, and caring. Students were also expected to perceive mothers displaying authoritative parenting as more effective, helpful, and caring than other parenting styles. In contrast, students were expected to perceive fathers displaying authoritarian parenting as more effective, helpful, and caring than other parenting styles. It was expected that Indian students would more frequently select authoritarian parenting as the style representing their own parent as well as other parents in their community, while US students would more frequently select authoritative parenting as the style representing their own parent as well as other parents in their community. Given the cultural shift in India due to forces of globalization, we expected that both Indian and US students would select authoritative parenting style as the one they would like to employ in the future when they become parents.

Method

Participants

Participants included 226 (41 % male, 59 % female) college students in India and 517 (38 % male, 62 % female) college students from the United States (US). Participants in India were recruited through announcements made in introductory undergraduate psychology classes at two colleges in a large metropolitan city in the northwestern state of Gujarat. Students attending such suburban colleges typically come from middle- to upper-middle-class families and stay at home with their parents while attending college. Participants in the US were recruited through the psychology department undergraduate participant pool that largely consistent of students enrolled in first-year introductory psychology courses at a mid-sized university in Southwestern Ohio, an institution that typically attracts students from European American upper-middle-class family backgrounds. These students typically stay in residence halls or private housing near campus. Neither Indian nor US students were exposed to Baumrind’s parenting style typology through their introductory psychology course curriculum, however, US students may have had some exposure to adaptive parenting approaches through their high school life skills curriculum. The mean ages were 20.12 years (SD = 1.54) for the Indian participants and 18.72 years (SD = .88) for the US participants. The US sample was exclusively European American students to avoid confounds of ethnicity. A majority of the Indian sample (87.6 %) identified as Hindu. Religious affiliation was not collected for the US sample, though based on university-wide statistics regarding the make-up of its student body (78 % of the students reporting Christianity as their religious preference), a majority of US students were likely from families that identified as Christian.

Procedure

Pilot testing. The hypothetical vignettes developed for this study (see Appendix) were pilot tested with a separate sample of students (n = 38) enrolled in an advanced developmental psychology course at a mid-sized university in Southwestern Ohio. Baumrind’s typology was part of the course curriculum, and the students were familiar with the construct. These students were provided with three vignettes and two questions pertaining to each vignette. They were first asked which of Baumrind’s parenting styles was represented by the parent in the vignette, and they chose from three options (authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive). They were then asked the extent to which the description in the vignette captured the parenting style that they selected, and responses were provided on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = completely). The findings indicated that all students selected the intended parenting style in each of the three vignettes. Moreover, the students considered each vignette as an accurate representation of the intended parenting style (see Table 1).

With respect to the main study, all procedures in India took place in Gujarati, the participants’ first language, while all procedures in the US were completed in English. Written informed consent was obtained from participants in India and the US in participants’ native language prior to administration of the questionnaires. Participants completed a demographic information questionnaire and the parenting styles vignettes questionnaire that were translated from English to Gujarati and back translated to ensure conceptual and linguistic equivalence. In each country, approximately half of the participants were randomly assigned to complete the parenting styles vignettes questionnaire pertaining to mothers’ parenting style and the remaining half completed the same questionnaire, but a version that pertained to fathers’ parenting style. One hundred participants were targeted for each condition in each country to allow adequate power to test study hypotheses. Both the pilot test and main study were approved by the institutional review board at the first author’s academic institution.

Measures

The demographic information questionnaire asked the participant about their age, gender, ethnicity (for the US sample), and religion (for the Indian sample).

The parenting styles vignettes questionnaire included three hypothetical vignettes, each representing one of the three parenting types: authoritarian, permissive, and authoritative (see Appendix), followed by a series of questions. Each vignette described the same interpersonal situation between the parent and his or her two children, a 7 year-old boy and an 11 year-old girl (i.e., the children would like to play when it is time to complete schoolwork). What differed across vignettes is the way in which the parent responded to the interpersonal situation, representing each of the three parenting styles. After the presentation of each vignette, three questions were included, asking the participant to indicate the extent to which they perceived the parent in the vignette to be effective, the extent to which they perceived the parent’s approach to be helpful, and the extent to which they perceived the parent to be caring towards his or her children. The participants responded on a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 = not at all, 4 = somewhat, and 7 = very effective/helpful/caring. The internal consistency of responses to authoritarian, permissive, and authoritative vignettes was acceptable in the Indian (.69, .76, and .79, respectively) and US samples (.77, .68, and .83, respectively). After the presentation of all three vignettes and corresponding questions, three overall questions were asked. These questions asked the participant to choose the parenting style (from those depicted in the three vignettes) that represented their own parent’s parenting approach while they were growing up, the one that was most commonly used by parents in their hometown, and the one that the participants themselves would be most likely to use if/when they became a parent.

Results

The design of the study was a 2 (culture) × 2 (student gender) × 2 (parent gender) × 3 (parenting style) mixed-design. Culture, student gender, and parent gender were between-subjects factors. Parenting style was a within-subjects factor. Participants’ perceptions of effectiveness, helpfulness, and level of caring were dependent variables. Repeated measures ANOVAs were used to analyze main effects and interactions. The Bonferroni correction was used to assess the significance of all effects, and was computed as a α = .05/number of comparisons for each main effect or interaction.

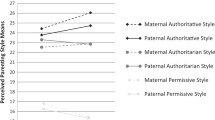

For perceived effectiveness of parenting style, results showed a significant interaction between parenting style and culture (F (2,724) = 40.10, p < .01, partial η 2 = .10) and a significant interaction between parenting style and student gender (F (2,724) = 4.65, p = .01, partial η 2 = .01). Consistent with the hypothesis, post hoc analyses showed that US participants rated authoritative parenting as more effective than Indian participants (p < .05). Contrary to the hypothesis, US participants also rated authoritarian parenting as more effective than Indian participants (p < .01), while Indian participants rated permissive parenting as more effective than US participants (p < .01) (see Table 2 for means and standard deviations). Additionally, as predicted, post hoc analyses showed that females rated authoritative parenting as more effective than males (p < .01).

For perceived helpfulness of parenting style, results showed a significant interaction between parenting style and culture (F (2,727) = 31.37, p < .01, partial η 2 = .08) and a significant interaction between parenting style and student gender (F (2,727) = 12.00, p < .01, partial η 2 = .03). Post hoc analyses showed that, as predicted, US participants rated authoritative parenting as more helpful than Indian participants (p < .01). Contrary to the prediction, US participants also rated authoritarian parenting as more helpful than Indian participants (p < .01), while Indian participants rated permissive parenting as more helpful than US participants (p < .01) (see Table 2 for means and standard deviations). Additionally, as predicted, post hoc analyses showed that females rated authoritative parenting as more helpful than males (p < .01). Contrary to the prediction, males rated permissive parenting as more helpful than females (p < .05).

For perceived caring of parenting style, results showed a significant main effect of culture (F (1) = 15.68, p < .01, partial η 2 = .02) and a significant interaction between parenting style and culture (F (2,726) = 11.71, p < .01, partial η 2 = .03). Post hoc analyses showed that, as predicted, US participants rated authoritative parenting as more caring than Indian participants (p < .05) (see Table 2 for means and standard deviations). Contrary to the prediction, US participants also rated authoritarian parenting as more caring than Indian participants (p < .01). Contrary to the prediction, no significant main effect or interactions of student gender were found.

Crosstabulations and Chi-square tests were used to analyze participants’ perceived normativeness (i.e., parenting style most reflective of their own parent, the style they would like to use in the future, and the styles of parents in their community). In the selection of the style most representative of their own parent, a majority of Indian and US participants selected the authoritative parenting style. Contrary to the prediction, a higher percentage of US participants chose the authoritarian style than Indian participants (χ 2(1) = 50.16, p < .01). In contrast, a higher percentage of Indian participants chose permissive (χ 2(1) = 20.22, p < .01) and authoritative styles (χ 2(1) = 8.71, p < .01) than their US counterparts. See Table 3 for all percentages. Specifically in India, a higher percentage of females students selected authoritative parenting as most representative of their own parent than males (χ 2(1) = 5.86, p < .05).

In the selection of the style most representative of parents in their home community, participants across cultures and genders seemed equally likely to choose any one of the three styles as most representative with no significant differences (see Table 3). The only significant difference was that a higher percentage of females in the US selected authoritative parenting as representative of parents in their community than US males (χ 2(1) = 4.31, p < .05).

In the selection of the style they would most wish to use in the future, a majority of US and Indian participants selected the authoritative parenting style. Consistent with the prediction, a higher percentage of US participants selected the authoritative style than Indian participants (χ 2(1) = 12.90, p < .01). Contrary to the prediction, a higher percentage of Indian participants selected the permissive style than US participants (χ 2(1) = 25.50, p < .01). In the Indian sample, males more often selected authoritarian parenting than females (χ 2(1) = 5.55, p < .05), while Indian females were more likely to select authoritative parenting (χ 2(1) = 4.99, p < .05). In the US sample, males were more likely to select permissive parenting style than females (χ 2(1) = 10.23, p < .01), while females were significantly more likely to select authoritative parenting (χ 2(1) = 12.40, p < .01).

Discussion

Utilizing a new vignette based measure, our results suggested that college students’ perceptions of parenting style differed as a function of their gender and culture, while few differences emerged as a function of parent gender.

Cultural Differences in Perceptions of Parenting Style

Supporting the original hypotheses, US participants considered authoritative parenting as more effective, helpful, and caring than Indian participants. A majority of US participants selected authoritative parenting as a style most representative of their own parents, as well as a style they would like to employ in the future if they were to become parents. Overall, these findings are consistent with the previous literature that demonstrated authoritative parenting is more commonly utilized and endorsed by European American parents (Baumrind 1971; Darling and Steinberg 1993; Maccoby and Martin 1983). Additionally, previous literature has suggested authoritative parenting is more common in Western cultures than Eastern cultures, in which authoritarian parenting is most common (Garg et al. 2005; Jambunathan and Counselman 2002).

Contrary to the hypotheses, US participants also considered authoritarian parenting as more effective, helpful, and caring than Indian participants, and Indian participants considered permissive parenting as more effective and helpful than US participants. Also contrary to the expectation, a higher percentage of US participants chose authoritarian parenting as the style most reflective of their own parents than Indian participants. In contrast, a higher percentage of Indian participants chose permissive and authoritative styles a representative of their own parents more than US participants. A higher percentage of Indian participants also selected permissive parenting as the style they would employ in the future if there were to become parents than US participants. Overall, these findings are inconsistent with the previous literature that demonstrated that Indian adolescents were more likely to report their mothers as using authoritarian parenting, while European Canadian adolescents were more likely to consider their mohters as using authoritative parenting (Garg et al. 2005). The expected likelihood of authoritarian parenting styles in Asian cultures is consistent with the socialization goals of interdependence and obedience, while authoritative parenting styles in Western cultures are consistent with the goals of independence and autonomy (Keller and Otto 2009). The present findings are inconsistent with previous findings that demonstrated higher prevalence of authoritarian parenting in India and theories concerning socialization goals of interdependence.

One explanation of these unexpected findings—that Indian college students considered permissive parenting as more helpful and effective and selected this as a style they would employ in the future more than US students—may be found in ethnographic accounts of Indian parenting. Kurtz (1992) contrasts the process of socialization in the West—in which the emphasis is on the child initially obeying external parental commands, and subsequent internalization of those commands—with the process in India. According to Kurtz, socialiation is a subtle process in India, where the focus is on children learning to voluntarily modify their behavior in response to subtle messages received from others rather than following explicit parental commands. Perhaps the description of the permissive parent in our vignette-based measure most closely aligns with a type of parenting in which there is a low level of explicit parental control combined with high warmth. It is likely that our Indian participants assumed that the permissive parent in our hypothetical vignette was implicitly conveying to the children which behavior was appropriate without explicitly communicating his or her expectation. Measures of parenting style have tyically assessed explicit parental control, and in future cross-cultural research, it would be important to distinguish between explicit and implicit forms of parental control, and include an assessment of both forms.

Another explanation of these unexpected findings—that Indian college students considered permissive parenting as more helpful and effective and selected this as a style they would employ in the future more than US students—may be related to processes of globalization. Much of the existing cross-cultural literature may be dated due to the increasing rate of globalization and modernization, particularly in suburban middle-class communities in Asian countries such as India. Patel-Amin and Power (2002) found that with the increasing modernization of India came changing attitudes in parenting, including more individualistic values. Due to advances in technology, particularly the younger generation has increased access to Western media and culture that may emphasize more permissiveness and autonomy granting in parenting behaviors over values such as obedience to parents. It is likely that such messages communicated through the media influence the perceptions of effective parenting of the younger generation, like the college students in the present study. Additionally, previous research has also shown that parenting by fathers in India has been changing over the years, becoming more nurturing and involved, suggesting a shift towards Western, individualistic values (Roopnarine et al. 1990). Such a shift in the attitudes and behaviors of the parent generation may indicate greater relinquishing of parental control and increased autonomy granting. Thus, a new cohort of parents and their college aged children may represent changing perceptions of parenting compared to older generations that participated in previous cross-cultural research.

Gender Differences in Perceptions of Parenting Style Within and Across Cultures

Consistent with the prediction, regardless of culture, females rated authoritative parenting as more effective and helpful than males, while contrary to the prediction, males rated permissive parenting as more helpful than females. An interaction between participants’ culture and gender revealed that in India, a higher percentage of females selected authoritative parenting as most representative of their own parents and as a style they would most like to employ in the future, while a higher percentage of males selected authoritarian as most representative of a style they would like to employ in the future. In the US, a higher percentage of females selected authoritative parenting as most representative of the style they would most like to employ in the future, and as representative of parents in their home community than males. Contrary to the prediction, a higher percentage of US males selected permissive parenting as most representative of the style they would like to employ in the future than females.

Overall, these findings demonstrated differences in perceptions of parenting style as a function of student gender in the expected direction. Previous research has found that across cultures females report more authoritative parenting than males, who report more authoritarian parenting than females (Conrade and Ho 2001; Lytton and Romney 1991; Someya et al. 2000). There has been conflicting evidence on the prevalence of permissive parenting, while endorsements of authoritarian and authoritative parenting remain fairly consistent across the literature (Russell and Aloa 1998; Conrade and Ho 2001). This may explain the unexpected findings of US males being more likely to select the permissive style as the style they would use in the future as a parent.

Contrary to the prediction, no significant differences concerning parent gender emerged. As Smetana (1995) suggested, parents and children may have different perceptions of the same parenting practices. Perhaps this discrepancy applies to parent gender, where a child may not perceive parenting as different between mothers and fathers, but mothers and fathers themselves might view their parenting differently. Much of the research supporting differential parenting based on parent gender incorporated parent reports (Russell and Aloa 1998; Winsler et al. 2005). Thus, the lack of findings concerning parent gender in the present study may be related to reporter characteristics.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study included upper-middle class college students from Midwestern US and Northwestern India. Both of these are diverse countries with significant regional and socioeconomic differences. Thus, our samples may not be representative of similar-aged emerging adults of other socioeconomic statuses or geographic regions. Additionally, the present study relied on self-report of participants that captured their perceptions of parenting styles, which may or may not correspond with actual parenting behaviors. College students’ perceptions of what they consider to be effective parenting may also be influenced by social desirability concerns. Nonetheless, the use of hypothetical vignettes and an assessment of explicit perceptions of parenting style may prove to be an effective measurement tool in parenting style research. Given our unexpected findings particularly related to the Indian participants, future research may focus on two important directions. First, within-culture comparisons of parenting style in rural or inner-city traditional families and suburban middle-class families in India may provide insights into cultural shifts in parenting as a function of modernization. Further exploration of culture and gender in studies of parenting may also be helpful as a function of modernization. Second, the construct of parenting style and its measurement tools have traditionally focused on explicit forms of parental behavioral control and warmth. Future research may incorporate an assessment of implicit parental control and warmth to capture a wider range of parenting approaches.

Despite these limitations, the present study contributed to scarce literature concerning the intersecting influence of youth’s culture, gender, and parent gender in perceptions of parenting style. Such examinations contribute to developing a culturally informed theory of parenting with implications for understanding parenting influences on youth outcomes in diverse families around the world.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monographs, 4(1, Pt. 2), 1–102.

Block, J. H. (1981). The child-rearing practices report (CRPR); A set of Q items for the description of parental socialization attitudes and values. Berkeley: University of California, Institute of Human Development.

Buri, J. R. (1991). Parental authority questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57(1), 110–119.

Chao, R. (2000). The parenting of immigrant Chinese and European American mothers: Relations between parenting styles, socialization goals, and parental practices. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21(2), 233–248.

Conrade, G., & Ho, R. (2001). Differential parenting styles for fathers and mothers: Differential treatment for sons and daughters. Australian Journal of Psychology, 53(1), 29–35.

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Developmental Psychology, 113(3), 487–496.

Garg, R., Levin, E., Urajnik, D., & Kauppi, C. (2005). Parenting style and academic achievement for East Indian and Canadian adolescents. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 36, 653–661.

Jambunathan, S., & Counselman, K. (2002). Parenting attitudes of Asian Indian mothers living in the United States and in India. Early Child Development & Care, 172(6), 657–662.

Keller, H., & Otto, H. (2009). The cultural socialization of emotion regulation during infancy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(6), 996–1011.

Kurtz, S. N. (1992). All the mothers are one: Hindu India and the cultural reshaping of psychoanalysis. New York: Columbia University press.

Lamborn, S. D., Mounts, N. S., Steinberg, L., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development, 62(5), 1049–1065.

Leung, K., Lau, S., & Lam, W. L. (1998). Parenting styles and achievement: A cross-cultural study. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 44, 157–172.

Lytton, H., & Romney, D. (1991). Parents’ differential socialization of boys and girls: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 109(2), 267–296.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In P. H. Mussen & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Natarajan, A. D., Raval, V. V., Raval, P. H., Trivedi, S. S., & Barnhart, C. M. (2010, July). Culture and perceived parenting style: Implications for interpersonal and academic functioning in Indian and American college students. In V. V. Raval (chair), Parenting and youth well-being in Gujarat, India. Paper presented at The 21st Biennial Meeting of the International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development, Lusaka, Zambia.

Patel-Amin, N., & Power, T. (2002). Modernity and childrearing in families of Gujarati Indian adolescents. International Journal of Psychology, 37(4), 239–245.

Poole, M., Sundberg, N., & Tyler, L. (1982). Adolescents’ perceptions of family decision-making and autonomy in India, Australia, and the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 13(1), 349–357.

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olson, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77, 819–830.

Roopnarine, J. L., Talukder, E., Jain, D., Joshi, P., & Srivastav, P. (1990). Characteristics of holding, patterns of play, and social behaviors between parents and infants in New Delhi. India. Developmental Psychology, 26(4), 667–673.

Rothbaum, F., & Trommsdorff, G. (2007). Do roots and wings complement or oppose on another? The socialization of relatedness and autonomy in cultural context. In J. G. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 461–489). New York: Guilford press.

Rudy, D., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Authoritarian parenting in individualist and collectivist groups: Associations with maternal emotion and cognition and children’s self-esteem. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(1), 68–78.

Russell, A., & Aloa, V. (1998). Sex-based differences in parenting styles in a sample with preschool children. Australian Journal of Psychology, 50(2), 89–99.

Saraswathi, T. S., & Pai, S. (1997). Socialization in the Indian context. In H. S. R. Kao & D. Sinha (Eds.), Asian perspectives in psychology: Cross-cultural research and methodology series (Vol. 19, pp. 74–92). New Delhi: Sage.

Shek, D. T. L. (1999). Parenting characteristics and adolescent psychological well-being: A longitudinal study in a Chinese context. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 125, 27–44.

Smetana, J. (1995). Parenting styles and conceptions of parental authority during adolescence. Child Development, 66(2), 299–316.

Someya, T., Uehara, T., Kadowaki, M., Tang, S., & Takahashi, S. (2000). Effects of gender difference and birth order on perceived parenting styles, measured by the EMBU scale, in Japanese two-sibling subjects. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences, 54(1), 77–81.

Sorkhabi, N. (2005). Applicability of Baumrind’s parent typology to collective cultures: Analysis of cultural explanations of parent socialization effects. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(6), 552–563.

Winsler, A., Madigan, A., & Aquilino, S. (2005). Correspondence between maternal and paternal parenting styles in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20(1), 1–12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Hypothetical Vignettes (Mother Version, US)

Note that culturally appropriate names were substituted for US father version and for India mother and father versions.

Appendix: Hypothetical Vignettes (Mother Version, US)

Authoritarian

Tammy is a mother of two, Eddie (age 7) and Stephanie (age 11). Tammy believes that she knows what is best for her children, and that children should do what their parents expect without asking questions. In one particular situation, when Eddie and Stephanie came home from school, they wanted to go outside to play. When Tammy told them that they have to finish all of their homework before they could go outside to play with their friends, Eddie and Stephanie became upset. Tammy responded that there would be no further discussion on the matter, and the children had to listen to her and respect her authority.

Permissive

Michelle is a mother of two, Charlie (age 7) and Alexis (age 11). Michelle believes that parents should not put restrictions on their children, and that while growing up, children should be free to do what they want. In one particular situation, Alexis and Charlie came home from school and wanted to go outside to play. Michelle asked them if they had any homework, and the children said that they did have homework but did not want to do it right then. Michelle immediately agreed and let them go outside to play for as long as they want.

Authoritative

Joanne is a mother of two, Johnny (age 7) and Sally (age 11). Joanne believes that parents should establish rules in the family, explain the reasoning, and encourage children to discuss their questions and concerns about those rules. In one particular situation, Sally and Johnny came home from school and wanted to go outside to play. When Joanne reminded Johnny and Sally that they first needed to do their homework, Johnny and Sally started to get upset and said that they would not do their homework. Joanne listened to Johnny and Sally as they explained why they wanted to go outside first, and, ultimately, explained to the children the rules she had originally established which were clear that homework must be completed before going outside to play.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barnhart, C.M., Raval, V.V., Jansari, A. et al. Perceptions of Parenting Style Among College Students in India and the United States. J Child Fam Stud 22, 684–693 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9621-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9621-1