Abstract

Trust in supervisor and leadership contribute to positive employee outcomes. Employees are also affected by the feeling of being trusted by those supervisors (i.e., felt trust). In order to clarify the theoretical and functional interactions between trust in supervisor and felt trust, we propose and test a moderated mediation model predicting turnover intention and work engagement. Uncertainty management theory, social exchange theory, and self-determination theory underlie the pathways through which trust in supervisor and felt trust have an impact on employee turnover intention and engagement. Surveys were collected from a diverse sample of 208 employees. Tests of moderated mediation were performed using the PROCESS Macro (Hayes, 2012). Trust in supervisor and felt trust interact to reduce turnover intention via a reduction in workplace uncertainty, whereas felt trust increases engagement on the job through a deepening of the social exchange relationship (i.e., felt obligation) and self-determination (i.e., autonomy). Trust in supervisor and felt trust are not interchangeable. Felt trust plays a central role in the motivations of employees on the job, especially those that contribute to greater effort. Our study is the first to provide both theoretical and empirical evidence explaining why trust in supervisor and felt trust predict separate motivational outcomes. The contents of the study should guide future integration of the felt trust construct into models predicting employee attitudes and performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The supervisor-subordinate relationship is a critical aspect of the employee experience, and trust in one’s supervisor improves a variety of organizational outcomes including cooperation (De Cremer & Tyler, 2007), resource sharing (Mislin, Campagna, & Bottom, 2011), creativity (Ford & Gioia, 2000), engagement (Mone, Eisinger, Guggenheim, Price, & Stine, 2011), prosocial behaviors (Zhu & Akhtar, 2014), job satisfaction, job performance, and retention (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002). Recent studies have suggested that trust in supervisor alone, however, does not fully explain the role of trust in the supervisor-subordinate relationship (Brower, Lester, Korsgaard, & Dineen, 2009; Korsgaard, Brower, & Lester, 2014; Lester & Brower, 2003). Subordinates are also meaningfully affected by the feeling of being trusted by those supervisors (Deng & Wang, 2009; Lau, Lam, & Wen, 2014; Salamon & Robinson, 2008). Known as felt trust, this construct that has been shown to increase desirable organizational outcomes such as employee loyalty, organizational citizenship behaviors, and task performance (Deng & Wang, 2009; Lau et al., 2014).

Despite initial evidence that these separate yet related trust perceptions lead to desirable employee outcomes, limited research has theorized about or examined trust in supervisor and felt trust simultaneously (Lester & Brower, 2003). In fact, Fulmer and Gelfand (2012) note in a recent review of trust across organizational levels that “the vast majority of the literature focuses on employees’ trust [in others] and that there has been comparably little research on trust in employees (e.g., from leaders’ perspective) or on employees being trusted” (p. 1193). There have also been calls in the literature to “empirically examine the mediating processes involved [in the relationships between trust and hypothesized outcomes]” (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002, p. 621). In other words, a more nuanced approach is needed to provide unique insights when determining the impact of interpersonal trust perceptions in the workplace (e.g., Gillespie, 2003; Lewicki, McAllister, & Bies, 1998; McAllister, 1995; Shapiro, Sheppard, & Cheraskin, 1992; Zhu & Akhtar, 2014).

Accordingly, the current study draws upon three well-established theories—uncertainty management theory (Lind & van den Bos, 2002), social exchange theory (Blau, 1964), and self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000)—to demonstrate the distinct and interactive contributions of trust in supervisor and felt trust on employee turnover intention and engagement. Uncertainty management theory (Lind & van den Bos, 2002) explains why trust in supervisor is an essential resource for reducing the burdens of a complex social world and the potential for exploitation that subordinates experience. However, previous work has not addressed the role of felt trust in reducing uncertainty. Social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) proposes that trust emerges from reciprocity in a relationship and is used explain to how felt trust is especially critical to expanding the social exchange relationship between supervisor and subordinate. Finally, felt trust is expected to enhance feelings of competence and autonomy, which enhance workplace motivation according to self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000). These theoretical pathways can potentially explain why both trust in supervisor and felt trust drive turnover intention and engagement on the job.

Turnover intention, or the conscious willingness to leave one’s organization (Tett & Meyer, 1993), and engagement, or the global affective-cognitive motivational state comprised of an employee’s vigor, dedication, and absorption on the job (Schaufeli, Salanova, Bakker, & Gonzales-Roma, 2002), were selected as focal employee outcomes in this study for several reasons. First, these constructs represent previously established proximal outcomes of trust in supervisor (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002; Tabak & Hendy, 2016). However, research has yet to examine the simultaneous impact of trust in supervisor and felt trust on these outcomes. Therefore, this study serves to extend existing theory and evidence regarding the nomological network of trust perceptions in the supervisor-subordinate relationship. In fact, the hypothesized model and study results suggest that felt trust plays a more primary role than trust in supervisor in shaping the motivational workplace experiences that drive these employee outcomes.

Second, from a more practical perspective, recent literature recognizes engagement as a critical element to organizational success that is on decline among today’s employees (Saks & Gruman, 2014) and turnover, which is closely linked to turnover intentions (Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, 2000), as a costly and well-known organizational problem (Allen, Bryant, & Vardaman, 2010; Heavey, Holwerda, & Hausknecht, 2013; Li, Lee, Mitchell, Hom, & Griffeth, 2016). In order to maximize the practical impact of the research, we conceptualize and measure engagement as a single composite construct using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES; Schaufeli et al., 2002) rather than taking a narrow focus on any single subdimension. Scholars suggest that the UWES is ideal for use when the goal is to provide summative information and “capture global perceptions across a number of employee issues” (Byrne, Peters, & Weston, 2016, p. 1218). Therefore, the results of this study suggest that improving not just trust in supervisor, but felt trust as well, may be one way to help assuage the practical organizational problems of declining employee engagement and increasing costs of turnover. In sum, the current study contributes to both future theory building and the practical utilization of the felt trust construct in improving broadly meaningful employee outcomes.

Previous Research on Subordinate Trust Perceptions

Previous reviews have highlighted two definitions of trust as comprising the fundamental distinctions found in most other definitions (Dietz & De Hartog, 2006; Fulmer & Gelfand, 2012). Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman (1995) define trust as “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party” (p. 712). Rousseau, Sitkin, Burt, and Camerer (1998) offered a similar definition of trust as “a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another” (p. 395). Two important assumptions drawn from these definitions are: (1) trust involves the willingness to accept vulnerability and (2) that willingness to accept vulnerability stems from the positive expectations of that referent’s intentions, abilities, and behaviors. Employees who trust their supervisors assume that the actions and decisions of those supervisors will take into consideration the best interests of those employees and the work group. As a result, the employees are more willing to accept requests and directions they receive from the supervisor. However, employees not only feel trust toward their supervisors, they also perceive the degree to which others trust them (Lau, Liu, & Fu, 2007; Lau et al., 2014). In other words, employees who feel trusted perceive the positive expectations that others hold regarding the employee’s own intentions, abilities, and behavior.

Felt trust, or the perception that one is trusted by others, has recently been studied at the individual (Lau et al., 2007, 2014) and group levels (Salamon & Robinson, 2008). Limited research has addressed the predictors of felt trust. One study demonstrated that the value congruence between leader and follower predicts the follower’s felt trust (Lau et al., 2007). Employees could also feel more trusted when their supervisors take significant risks on them by allowing those employees more control, decision latitude, or visibility on high-profile projects. Regarding outcomes of felt trust, Lau et al. (2007, 2014) proposed that felt trust will influence subordinate performance by inducing a sense of obligation, empowering the employee as a vote of confidence, and enhancing feelings of self-efficacy. Felt trust has been shown to increase supervisor satisfaction and enhance employee loyalty (Deng & Wang, 2009). Furthermore, felt trust predicts task performance and organizational citizenship behaviors directed toward individuals by increasing an employee’s organizational-based self-esteem (Lau et al., 2014). Finally, Salamon and Robinson (2008) studied collective felt trust in 88 retail locations. Collective felt trust was measured by aggregating felt trust perceptions across employees in each location. The study not only found that employees who felt collectively trusted by management felt greater responsibility within their jobs, but that felt trust also improved sales and customer service performance of the units. The aforementioned studies provide initial evidence that felt trust has substantial effects on the experiences and performance of employees in organizations, but it is still unclear how trust in supervisor and felt trust relate to one another and interact to impact the subordinate experience. In sum, research is needed to explore the simultaneous roles of both trust in supervisor and felt trust in promoting desirable employee outcomes.

Uncertainty Management Pathway

Employees’ utilize trust perceptions as a means of reducing complexity in their work environment (Lewicki et al., 1998; Luhmann, 1979). Social relationships are particularly fraught with complexity and trust is essential for narrowing the scope of contingencies that individuals must be concerned with while cooperating with others (Lewis & Weigert, 1985). In the absence of trust in a relationship, individuals experience more uncertainty and must dedicate cognitive resources to evaluating the fairness and trustworthiness of those around them (van den Bos, 2001). According to fairness heuristic theory, subordinates face a fundamental social dilemma in the workplace in that cooperating with the demands of their supervisors maximizes their opportunities to gain rewards while simultaneously increasing the opportunities for the supervisor to act exploitatively (van den Bos & Lind, 2002). This fundamental uncertainty embedded in the relationships between subordinates and supervisors is pervasive throughout each individual’s work-life. Through making judgments about a supervisor’s fairness, subordinates determine whether they can trust their supervisors (Colquitt, LePine, Piccolo, Zapata, & Rich, 2012; van den Bos, Wilke, & Lind, 1998). Trusting employees no longer fear exploitation and experience more certainty on the job because they can expect their supervisors to act in competent, predictable, and benevolent ways (Colquitt et al., 2012; van den Bos & Lind, 2002). Building upon that insight, uncertainty management theory (Lind & van den Bos, 2002) proposes that the need to cope with uncertainty is constant in many domains of people’s lives, including the workplace, and both fairness perceptions and trust are fundamental to individuals feeling more certain.

Previous research has established the positive relationship between trust in supervisor and workplace certainty (Colquitt et al., 2012). However, empirical studies have not yet addressed the effect of felt trust on subordinates’ perceived certainty at work. Felt trust is also expected to increase feelings of workplace certainty because when a subordinate perceives that his/her supervisor is willing to be vulnerable based on positive expectations of the subordinate, the subordinate will also perceive that the supervisor intends to continue supporting that subordinate in the future (Korsgaard & Sapienza, 2002). Subordinates will also feel more secure about their employment as they feel valued by their supervisors’ trust in them. Furthermore, similar to the previously established finding that organizational citizenship behaviors are higher when the supervisor and subordinate trust one another (Brower et al., 2009), we suggest that employees will feel the most certainty at work when they simultaneously trust in their supervisors and feel trusted by their supervisors. Specifically, trust in supervisor serves to alleviate the fundamental social dilemma of subordination (van den Bos & Lind, 2002), and felt trust increases employees’ certainty that their supervisors value them and want to keep them employed. If employees trust their supervisors but do not feel trusted by them, they may feel expendable because they perceive that their supervisors are unwilling to rely on them. Alternatively, if employees feel trusted but cannot trust their supervisors, they could be in a position to take on extra responsibility without certainty about their supervisors’ ability or intent to reciprocate. Therefore, we propose an interaction effect in which workplace certainty is highest when both trust in supervisor and felt trust are high.

Hypothesis 1. Felt trust and trust in supervisor interact to reduce workplace uncertainty such that workplace uncertainty is lowest when both felt trust and trust in supervisor are high.

Subsequently, lower workplace uncertainty based on high levels of trust in supervisor and felt trust will reduce the intention to turnover because certainty enacts both affective and rational motivational forces. The combination of trust in supervisor and felt trust increases certainty, resulting in less threatening appraisals of the environment (Mishra & Spreitzer, 1998). According to uncertainty management theory (Lind & van den Bos, 2002), that increase in certainty will reduce subordinates’ stress on the job. The experience of salient negative emotions automatically activates the hedonistic behavioral-avoidance response in which individuals feel compelled to avoid the subject of the negative emotions (Maertz & Griffeth, 2004). Increased certainty will reduce the negative affective motivational forces that can lead subordinates to consider quitting. Additionally, the combination of trust in supervisor and felt trust increases certainty because subordinates anticipate their supervisors are motivated to act in those subordinates’ best interest and reciprocate positive interactions. Therefore, rational motives also compel employees to stay in workplace situations in which they feel more certain that their supervisors will support their goal attainment through reciprocating for high performance and will seek to rely upon them in the future. In sum, we propose a mediated moderation:

Hypothesis 2. The interactive effect of trust in supervisor and felt trust on turnover intention is mediated by workplace uncertainty.

In addition to reducing turnover intention, workplace certainty will increase employee engagement on the job. Workplace uncertainty can be a significant job demand for employees (Crawford, Lepine, & Rich, 2010). Job demands can be categorized as challenge stressors or hindrance stressors (Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, & Boudreau, 2000). Challenges stressors are appraised as demands that can be overcome to promote personal growth and future gains. Hindrance stressors are appraised as demands that impede personal growth, mastery, and achievement of meaningful goals. Uncertainty in the workplace acts as a hindrance stressor because employees cannot predict whether their efforts will result in personal mastery or goal achievement, and the affective-cognitive and behavioral resources directed toward resolving the uncertainty will reduce the resources available to direct toward the job itself. Conversely, the certainty that arises from the combination of high trust in supervisor and felt trust will free up affective, cognitive, and behavioral resources, allowing the employee to approach work with more vigor (i.e., energy), dedication (i.e., enthusiasm), and absorption (focus; Crawford et al., 2010). Therefore, we propose another mediated moderation such that reduced workplace uncertainty will mediate the positive interactive effect of trust in supervisor and felt trust on engagement.

Hypothesis 3. The interactive effect of trust in supervisor and felt trust on engagement is mediated by workplace uncertainty.

Social Exchange Pathway

Social exchange theory (SET) has been the most relied upon theoretical framework for explaining the role of trust in motivating employee attitudes and behavior (Fulmer & Gelfand, 2012). SET predicts that interpersonal trust emerges from the informal reciprocal exchange of valued resources within an interdependent relationship over time (Blau, 1964). Social exchanges do not include explicit bargaining of resources (Molm, Takahashi, & Peterson, 2000) because control systems such as contracts and contingent agreements circumvent the need for trust (Mayer et al., 1995). The development of a social exchange relationship relies on one actor making an initial move by providing a valued resource to another actor with the expectation that the recipient will reciprocate. As each party in the relationship reciprocates, their perceptions of trust in the other party will enable them to exchange increasingly valued resources (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Kramer, 1999). Therefore, within the SET framework, one party’s trust perceptions represent the extent to which the other party is expected to reciprocate in a discretionary manner.

Colquitt et al. (2012) argue that the key to operationalizing the effect of trust within the social exchange framework is through feelings of obligation. Felt obligation refers to the belief that one is morally obligated to respond to the support provided by an individual or organization by caring about the goals of that party (Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel, Lynch, & Rhoades, 2001). Subordinates experience increased felt obligation in response to resources received in the past and feel more motivated to put forth effort in order to discharge those feelings of obligation as a means of sustaining the social exchange relationship (Eisenberger et al., 2001; Eisenberger & Stinglhamber, 2011; Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997). Although individuals differ in the degree to which they feel obligated to reciprocate within exchanges (Clark & Mills, 1979; Eisenberger et al., 2001; Witt, 1991), there is a general norm of reciprocity across individuals and cultures because of its beneficial social implications (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Gouldner, 1960). Thus, felt obligation is a belief held by the subordinate toward the supervisor (or organization) regarding a felt need to reciprocate. This concept is distinguishable from felt trust, which refers to subordinates’ perceptions regarding the degree to which their supervisors’ trust that they (the subordinates) will reciprocate for any resources received.

Previous models testing the relationship between trust in supervisor and felt obligation have not addressed the role of felt trust in the supervisor-subordinate social exchange relationship (e.g., Colquitt et al., 2012). We propose that felt trust has a greater impact, as compared to trust in supervisor, on expanding social exchange relationships. Within the supervisor-subordinate exchange relationship, there is an inherently unequal distribution of valued resources. Supervisors are often the direct providers of many discretionary resources that their subordinates value (e.g., bonuses, special assignments, access to training; Rhoades, Eisenberger, & Armeli, 2001; Whitener, 2001). That greater access to resources allows supervisors to initiate the expansion of a social exchange relationship more so than the subordinates themselves (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Thye, 2000). Supervisors can initiate the expansion of an exchange relationship with a subordinate by demonstrating trust in that subordinate through delegating high-risk assignments or providing opportunities to lead an initiative (O’Donnell, Yukl, & Taber, 2012). We suggest that subordinates who perceive these relationship expansion behaviors, and therefore feel more trusted, will anticipate greater opportunities to develop new marketable skills and demonstrate competence in order to achieve promotions or pay increases in the future. As a result, subordinates who feel trusted will feel more obligated to put forth extra effort as a means of reciprocating and continuing to expand the social exchange relationship.

Trust in supervisor is not expected to predict felt obligation when felt trust is also included in the model. As stated earlier, because of the power differences inherent in the supervisor-subordinate relationship, subordinates have limited access to discretionary resources that the supervisor will find highly valuable. Therefore, subordinates have limited capability to initiate an expansion of the social exchange relationship. Even discretionary acts by a subordinate to support the organization (e.g., staying late, attending voluntary meetings) are increasingly viewed as a standard part of the job (Turnipseed & Wilson, 2009). This is particularly the case in high-performance organizations that emphasize employee involvement and autonomy (Kirkman, Lowe, & Young, 1999). If a subordinate is highly trusting of a supervisor, it means he or she is willing to rely on that supervisor based on their positive expectations of that supervisor’s competence and intent to reciprocate. The willingness to rely on one’s supervisor is not expected to increase felt obligation because it does not indicate an opportunity to expand the social exchange and therefore it should not trigger the felt obligation that felt trust is expected to trigger.

Hypothesis 4. Felt trust is positively related to felt obligation toward the supervisor.

As mentioned previously, felt trust has been shown to increase effort-driven behaviors such as task performance and organizational citizenship behaviors (Lau et al., 2014) as well affective outcomes such as loyalty (Deng & Wang, 2009). We extend these findings by suggesting that one of the reasons employees respond to felt trust by increasing their positive affect and effort (or in other words, become more engaged), is the increased feelings of obligation toward their organization and supervisor (Kahn, 1990; Saks, 2006). Felt trust increases engagement on the job by growing and strengthening the social exchange relationship between the supervisor and the subordinate and by creating a perceived need to have increased impact on the job as a means of relieving felt obligation (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, 2001). Employees are able to diffuse their feelings of obligation by showing more enthusiasm for their work and devoting more energy and focus to help the organization achieve its goals. Therefore, we propose that felt obligation will mediate the positive relationship between felt trust and engagement.

Hypothesis 5. The positive relationship between felt trust and engagement is mediated by felt obligation.

Felt trust is also expected to reduce turnover intention partially though an increase in felt obligation. Subordinates experiencing high levels of felt trust will be more motivated to stay in the organization in order to continue a favorable social exchange relationship (Shore & Barksdale, 1998). Furthermore, those subordinates will also feel morally compelled to remain in the organization in order to discharge the feelings of obligation from the resources they had received (Colquitt et al., 2012). This is similar to the normative commitment construct, which refers to an employee’s commitment to stay in the organization because of socialization processes and investments the organization has made in the employee in the past (Meyer & Allen, 1991). According to the norm of reciprocity, subordinates’ perception that they have remaining obligations toward the supervisor to discharge provides a motivational force to continue working until those debts have been paid (Eisenberger et al., 2001; Maertz & Griffeth, 2004; Robinson, Kraatz, & Rousseau, 1994). Therefore, subordinates who feel trusted by their supervisors will feel obligated to stay in order to continue receiving the benefits of a favorable exchange and to reciprocate the willingness of their supervisors to rely on them for important tasks.

Hypothesis 6. The negative relationship between felt trust and turnover intention is mediated by felt obligation.

Self-Determination Pathway

Self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2000) is a metatheory that explains how enhancing individuals’ perceptions of competence and autonomy increases intrinsic motivation, engagement, and well-being across many performance domains. Perceived competence at work refers to one’s confidence in his/her ability to perform the job tasks and to master job-relevant skills. Autonomy refers to acting according to one’s own volitions (Gagné & Deci, 2005). Cognitive-evaluation theory (CET), a subset of SDT, proposes that intrinsic motivation results from performing a task because it is intellectually stimulating or provides satisfaction in and of itself, and that extrinsic motivators (e.g., contingent bonuses, punishments, or surveillance) diminish intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). CET research demonstrated that enhancing both feelings of competence through positive feedback and maintaining autonomy through reducing the use of contingent rewards result in higher levels of intrinsic motivation (Deci, 1971; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan, 1982).

Later, self-determination theory expanded upon CET to include mechanisms for explaining how certain extrinsic outcomes of the task would still enhance overall motivation on the job (Ryan & Deci, 2000). SDT also included a third psychological need, relatedness. Relatedness refers to the satisfaction of feeling secure attachments with others, regardless of the nature of that exact attachment or relationship. Individuals value outcomes that help those they feel attachments toward and are motivated to perform actions to achieve those outcomes (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Gagné & Deci, 2005). SDT suggests that employees can still be highly motivated to perform tasks when employees identify their actions with accomplishing a self-selected goal or as consistent with their identity, interests, and motivation (Gagné & Deci, 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Interpersonal attachment has been shown to result from an emerging social exchange relationship (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Lawler, 2001; Molm et al., 2000). Within the hypothesized model, we suggest that the social exchange pathway (i.e., felt obligation) overlaps conceptually with the concept of relatedness in respect to the supervisor-subordinate relationship, and is expected to account for the impact of relatedness on motivation. Therefore, an additional variable representing the relatedness factor and related hypotheses were not included in the model.

In the case of both CET and SDT theories, sustaining autonomy and competence is essential for maintaining high levels of motivation. We expect that felt trust contributes strongly to both perceptions of autonomy and competence, but that trust in supervisor does not. Supervisor evaluations, attitudes, and behaviors communicate salient social information that subordinates utilize to interpret the workplace environment and their own role within it (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). Subordinates who feel trusted by their supervisors perceive that their supervisors are willing to rely upon them without exerting high levels of monitoring or control. By definition, subordinates who feel trusted will feel more able to make important decisions and complete tasks according to their own volitions without the expressed permission of their supervisors (Chen, Kirkman, Kanfer, Allen, & Rosen, 2007). As a result, subordinates experience more perceived autonomy on the job because their actions are consistent with their own volitions. When subordinates’ autonomous motivation is supported, they demonstrate increases in a variety of positive workplace outcomes including performance, persistence, and well-being (see Gagné & Deci, 2005 for review).

Furthermore, when a subordinate feels trusted, it is perceived as a vote of confidence from the supervisor in the subordinate’s ability to carry out a task and be relied upon (Lau et al., 2007). Lau et al. (2014) supported this view by demonstrating that felt trust was an antecedent of organization-based self-esteem. The authors suggest that from an attribution perspective (Tomlinson & Mayer, 2009; Weiner, 1985), subordinates attribute the positive expectations conveyed by felt trust to their self-concept, boosting their organization-based self-esteem. Similarly, it is expected that felt trust enhances subordinates’ perceived competence on the job. The subordinates’ trust in supervisor, however, does not serve as social information regarding the subordinate (i.e., it is not attributable to self-concept), and therefore, it is not expected to have an impact on competence or autonomy.

Satisfying the basic psychological needs of autonomy and competence has been shown to predict higher levels of motivation across culturally diverse samples (Deci et al., 2001). According to CET, enhancing the experience of autonomy and competence increases intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985), which subsequently enhances individuals’ level of willingness to perform tasks. Subordinates’ experience of autonomy is also crucial for self-identifying with work tasks, which will lead employees to feel more enthusiastic to perform extrinsically motivated tasks (Gagné & Deci, 2005). Therefore, by enhancing perceptions of autonomy and competence, felt trust is expected to result in higher levels of overall engagement on the job.

Hypothesis 7. The positive relationship between felt trust and engagement is mediated by autonomy and competence.

Additionally, employees experiencing high levels of autonomy via feeling trusted are also expected to desire to stay within the organization based on the positive fulfillment of those psychological needs (Liu, Zhang, Wang, & Lee, 2011; Spector & Jex, 1998). When employees perceive that they are trusted, they will seek to remain in those roles because they can act freely to achieve workplace goals in whichever way they prefer. By moving to another organization, they would be forfeiting the trust they felt they had built within their current relationships, with no guarantee that a future employer would be as trusting. Alternatively, employees’ increased perceptions of their own competence could increase turnover intention. Maertz and Griffeth (2004) explain that employees with high perceptions of their own competence, or self-efficacy, might be more willing to take on the risk of seeking other options outside the organization because they have greater market value. Therefore, felt trust is expected to produce competing indirect effects on turnover intention through competence and autonomy. More specifically, felt trust will reduce turnover intention through an increase in perceived autonomy on the job. However, felt trust will also increase turnover intention through an increase in perceived competence on the job.

Hypothesis 8. The negative relationship between felt trust and turnover intention is mediated by autonomy.

Hypothesis 9. The positive relationship between felt trust and turnover intention is mediated by competence.

In sum, the current model proposes three theoretical mediating pathways via which trust in supervisor and felt trust influence employee turnover intention and engagement. Based on the above theoretical development, trust in supervisor and felt trust are expected to interactively reduce workplace uncertainty leading to a reduction in turnover intention and an increase in engagement (Colquitt et al., 2012; Lind & van Den Bos, 2002; Luhmann, 1979). However, felt trust, as opposed to trust in supervisor, is expected to increase employee engagement by enhancing subordinates’ felt obligation in the social exchange relationship (Blau, 1964) as well as by enhancing employee self-perceptions of competence and autonomy vis-à-vis the self-determination pathway (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Finally, felt trust is expected to indirectly reduce turnover intention by increasing felt obligation and autonomy, but is also expected to indirectly increase turnover intention through increasing subordinates’ perceived competence. Overall, the hypothesized model suggests that felt trust plays a primary and underexplored role in shaping the workplace experiences that drive employee turnover intention and engagement.

Method

Sample and Procedure

A sample of 208 employees working at least 20 h per week was surveyed regarding their trust perceptions, motivation, turnover intention, and engagement on the job. The focal study variables were taken from a larger dataset that included measures of disclosure and power distance that were intended for an additional study outside of this theoretical framework. Participants were recruited through graduate student referrals by advertising the study on social media networks (76%) and the remaining sample was collected using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). MTurk data has been shown to be almost indistinguishable from data obtained from conventional laboratory research and other online samples (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Sprouse, 2011). MTurk participants are also more demographically diverse than typical American college student samples (Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, 2010).

All participants were provided a link to the online survey and asked to fill out a brief questionnaire about their manager and experience on the job. The respondents were sampled from a variety of industries with the largest representation being education (15%), healthcare, (12%), information technology (12%), and insurance (8%). Furthermore, the sample represented education levels ranging from high school graduates to postgraduate education. The gender composition was balanced (male 48%), average age was 35 years (SD 11.30), and average tenure on the job was 7.92 years (SD 6.32). To assure the data was of high quality, respondents who failed any one or more of four attention check items were removed from the sample. Participants were also removed from the sample if they rushed through the answers of the questionnaire (cutoff set at 2 standard deviations below the mean time to complete survey). Of the original 221 participants, 6% were removed based on these restrictions, resulting in an analyzed sample of 208. Additionally, MTurk participants were only invited to participate if they had a 95% approval rate for their responses to other requests on the website (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011).

Measures

Trust and Felt Trust

The reliance-based trust scale from Gillespie’s (2003) behavioral trust inventory (BTI) was utilized for both measures of trust in supervisor and felt trust. The full BTI includes two factors, reliance and disclosure, which are each comprised of five items. The theoretical arguments for this study pertain more to reliance than to disclosure-based trust, which involves shared identity, relational, and affect-based processes (e.g., Gong, Farh, & Chattopadhyay, 2012). Previous studies have demonstrated that disclosure-based felt trust was not predictive of workplace attitudes and performance (Lau, Lam, & Wen, 2014). For the measure of reliance-based trust, each item asked “how willing are you to” and was followed by a statement of reliance on the supervisor. For felt trust, each item was preceded by “How willing is your supervisor to…” and continued with a reliance-based statement with the subordinate as the referent. Lau et al. (2014) recently published a felt trust study utilizing the same scale design.

The strength of the BTI is that it emphasizes the willingness component of trust (Dietz & De Hartog, 2006). The perception of employees that those in power are willing to rely on them is central to the felt trust construct. Other trust measures do not address the trusting party’s willingness to let another party have a significant influence on their life (Schoorman et al., 2007). McEvily and Tortoriello (2011) point out that most published measures of trust actually measure trustworthiness, which is conceptually different (Mayer & Davis, 1999). Furthermore, a review of the interpersonal trust measures by McEvily and Tortoriello (2011) demonstrated that the BTI had high reliabilities compared to several of the other measures and can be directed toward several different referents. The items used in other measures (e.g., Mayer & Davis, 1999; McAllister, 1995) are worded in such a way that changing the referents to reflect felt trust would have likely caused confusion. The BTI is designed specifically for person-to-person measurement of trust (Gillespie, 2003). As a result, the five-item measure with the adjusted referent is most suitable to the purposes of the study. Answers to the item statements are indicated using a scale of 1 = not at all willing to 7 = completely willing, and the measure demonstrated coefficient alphas of .89 for trust in supervisor and .88 for felt trust.

Workplace Uncertainty

Workplace uncertainty was measured using three items from the measure of Colquitt et al. (2012) based on the uncertainty management theory (van den Bos & Lind, 2002; e.g., Many things seem unsettled at work currently). Answers to the item statements are indicated using a scale of 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree, with higher scores indicating higher amounts of perceived uncertainty. The coefficient alpha for the scale was .85.

Felt Obligation

Felt obligation was measured using five items from the measure of Eisenberger et al. (2001) with supervisor as the referent (e.g., I feel a personal obligation to do whatever I can to help my supervisor achieve his or her goals; I owe it to my supervisor to give 100% of my energy to his or her goals while I am at work). The items were measured using a 7-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. While the measure was originally intended for use with organization as the referent, both judgments are upward in nature and supervisor relationships are highly related to judgments about the organization (Eisenberger et al., 2001). The coefficient alpha for the scale was .84.

Autonomy and Competence

Perceived autonomy (e.g., I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job) and competence (e.g., I am confident about my ability to do my job) were both measured with three items (Spreitzer, 1995). The items were measured using a 7-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The coefficient alphas were .81 for competence and .82 for autonomy.

Turnover Intention

The intention to turnover was measured using two items adapted from Hom and Griffeth (1991) and Jaros (1997). They read, “I often think about quitting this organization” and “I intend to search for a position with another employer within the next year.” The items are measured using a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree and the coefficient alpha was .82.

Engagement

Engagement was measured using the UWES (Schaufeli et al., 2002). The items are measured using a 6-point frequency scale ranging from 1 = never to 6 = always and demonstrated a coefficient alpha of .95. Example items include “I can continue working for very long periods at a time” and “At my work, I always persevere, even when things do not go well”. The subdimensions include vigor, dedication, and absorption, but the current study used the entire scale as a composite variable.

Controls

Tenure, age, and level of education were also collected as control variables to reduce confounding effects. Tenure and age have been shown to effect turnover and turnover-related constructs (Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, 2000). Education, age, and tenure are also expected to influence workers’ perceived autonomy, competence, and their sense of obligation to managers.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The coefficient alphas, means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations for the study variables are displayed in Table 1. Trust in supervisor and felt trust were strongly correlated, r = .63; p < .05, though not so strongly as to suggest construct redundancy. Construct uniqueness was further explored via confirmatory factor analysis of competing measurement models.

Measurement Models

To test the eight-factor measurement model proposed and provide initial evidence of construct validity, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using MPlus 5.1 data analysis software (Muthén & Muthén, 2008). Two alternative models were also examined. The eight-factor measurement model including both trust constructs, the four mediators, and two dependent variables, demonstrated the best overall fit to the data and good fit overall: χ2(436) = 666.48, p < .001, comparative fit index (CFI) = .94, standardized root mean residual (SRMR) = .06, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .05. The eight-factor model outperformed a seven-factor model with the two trust perception measures collapsed into a single factor: Δχ2(7) = 216.57, p < .001. The eight-factor model also demonstrated significantly better fit than a seven-factor model which collapsed felt trust and felt obligation: Δχ2(7) = 206.68, p < .001. Lastly, all factor loadings of scale items onto latent constructs were statistically significant. Therefore, the data supports discriminating between trust in supervisor and felt trust, as well as the rest of our measurement model, enabling further hypothesis testing.

Hypothesis Testing

Uncertainty Management Pathway

Hypotheses 1 through 3 were tested using Model7 from the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2012). The PROCESS macro is preferable for analyzing indirect effects and conditional indirect effects using a bootstrapping approach (Kisbu-Sakarya, MacKinnon, & Miočević, 2014). Model7 estimates the conditional indirect effect using the bootstrapping procedure of Preacher et al. (2007), which is recommended because it increases statistical power to avoid type 1 errors (Mackinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Bootstrapping produces confidence intervals by resampling to create a distribution of indirect effects. Confidence intervals that exclude zero demonstrate evidence of a significant indirect effect. Evidence of a conditional indirect effect is determined by the index of moderated mediation, which indicates that differences in the indirect effects based on variation in the moderator are significantly different (Hayes, 2015). Mean centering was used for product terms and all path coefficients are unstandardized OLS regression coefficients (Hayes, 2017).

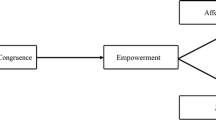

The interactive effect of trust in supervisor and felt trust was significant in predicting workplace uncertainty, b = − .15; p = .01 (Table 2). Figure 1 demonstrates that the combination of high trust in supervisor and high felt trust resulted in the lowest workplace uncertainty, thus supporting Hypothesis 1. Hypothesis 2 proposed a conditional indirect effect of trust in supervisor on turnover intention through workplace uncertainty when felt trust is high. When controlling for felt obligation, competence, autonomy, and age, the relationship between workplace uncertainty and turnover intention was significant, b = .59, p < .0001. The index of moderated mediation was significant at IMM = − .09; CI [− .16, − .02]. Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes (2007) recommend operationalizing the indirect effect at different levels of the moderator. Table 2 displays the operationalized indirect effect of trust in supervisor on turnover intention through workplace uncertainty at low, medium, and high levels of felt trust. As expected, the indirect effect of trust in supervisor on turnover intention via workplace uncertainty is significant only when felt trust is at medium and high levels, supporting Hypothesis 2. The results were nearly identical with the control variables removed from the model. The same procedure was performed to test Hypothesis 3, which proposed a conditional indirect effect of trust in supervisor on work engagement through workplace uncertainty when felt trust is high, but there was no significant relationship between workplace uncertainty and work engagement, and the confidence intervals for the index of moderated mediation included zero. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was not supported.

Social Exchange Pathway

Hypotheses 4 through 9 were tested using Model4 from the PROCESS macro. Two mediation models were tested with engagement and turnover intention as the dependent variables. Trust in supervisor was included as a control variable for the mediators and dependent variables in both models, and age was included as a control variable for turnover intention. Workplace uncertainty was included in the turnover intention model since it demonstrated a significant effect. Table 3 displays the direct and indirect effects for each of the models.

Felt trust was significantly related to felt obligation, b = .44; p < .0001, supporting Hypothesis 4, whereas trust in supervisor was not significantly related to felt obligation. The indirect effect of the relationship between felt trust and work engagement through felt obligation was significant, indirect effect = .14; CI95% [.06, .25], supporting Hypothesis 5. Felt obligation did not mediate the relationship between felt trust and turnover intention. Therefore, Hypothesis 6 was not supported.

Self-Determination Pathway

The indirect effect of felt trust on work engagement via autonomy was supported, indirect effect = .13; CI95% [.07, .22], but the indirect effect through perceived competence was not. Therefore, Hypothesis 7 is partially supported. The indirect effects of felt trust on turnover intention through autonomy, indirect effect = − .08; CI95% [− .16, − .04], and competence, indirect effect = .06; CI95% [.01, .12], were significant, supporting Hypotheses 8 and 9. Notably, the indirect effects of autonomy and competence were in opposite directions, as hypothesized. As a supplementary analysis, all hypotheses were also tested using the single indicator approach to structural equation modeling (results available by request from the first author), and this model demonstrated the same pattern of relationships.

Discussion

Interpersonal trust has been lauded as a vital resource in the workplace (Dirks & Ferrin, 2001, 2002); however, the precise explanation for how the trust between a supervisor and subordinate influences workplace attitudes and outcomes continues to develop. Furthermore, the feeling of being trusted has been excluded from many previously tested models. Based on previous theory and research (Brower et al., 2009; Colquitt et al., 2012; Lau et al., 2014), we proposed and tested three theoretical pathways explaining the unique and interactive roles of trust in supervisor and felt trust in predicting employee turnover intention and engagement. Overall, the results suggest that previous studies that omitted felt trust were missing a key predictor when analyzing outcomes of the supervisor-subordinate relationship.

According to the uncertainty management theory (van den Bos & Lind, 2002), individuals seek information to judge authority figure’s trustworthiness in order to resolve the fundamental social dilemma of subordination. Mainly, the more effort one puts forth, the greater the opportunity for exploitation. However, our results suggest that within the workplace, trust in an authority figure alone might not be enough to reduce perceptions of uncertainty. Both trust in supervisor and felt trust are needed to reduce uncertainty for subordinates. Additionally, workplace uncertainty mediated the relationship between trust in supervisor and turnover intention when felt trust was also high. Felt trust provides important social information for resolving uncertainty because it relates to the subordinate’s perception that the supervisor will engage in greater interdependence and shared responsibility for meaningful workplace goals and tasks. An employee who feels trusted will feel less uncertainty because they are an indispensable resource to the authority figure. Since trust is fundamental to all social exchanges (Blau, 1964), a lack of felt trust would produce great uncertainty about the availability of resources in the future. Someone who does not feel trusted anticipates losing out on valuable exchanges with others. Our results demonstrate that trust in supervisor, as predicted by uncertainty management theory, is still critical because it reduces fears of exploitation. Employees who feel trusted, but do not trust their supervisors, could perceive opportunity to take more responsibility but fear having the rewards of their efforts diminished by that supervisors’ incompetence or willingness to exploit them. In that case, the lack of certainty could still compel an employee to leave the organization.

Our results also demonstrated that decreased workplace uncertainty reduced turnover intention, but did not increase engagement when accounting for the other mediators. The motivation to stay in an organization and the motivation to put forth high levels of effort likely come from different sources. Individuals will be motivated to stay in environments in which they can benefit from their relationships with authority figures (Costigan, Insinga, Berman, Kranas, & Kureshov, 2011). However, removing the hindrance demand of uncertainty might not have a great effect of engagement. Employees experiencing high levels of certainty at work could rely on others through social loafing and actually decrease in effort. It is possible that the motivational forces of felt obligation, autonomy, and competence likely have much greater effects on employees’ engagement on the job.

The effect of felt trust and the absence of an effect from trust in supervisor on the social exchange and self-determination pathways are important theoretical and practical contribution. Many studies have proposed that trust in supervisor is related to effort and performance because it represents an expansion of the social exchange relationship (Colquitt et al., 2012). Our results demonstrate that when felt trust is included in the analyses, the relationship between trust in supervisor and felt obligation is attenuated. Additionally, felt obligation mediates the relationship between felt trust and engagement. When employees perceive that their authority figures trust them, they feel compelled to respond to that trust and demonstrate greater effort on the job. Without feeling trusted by an authority figure, employees do not perceive an opportunity to grow the social exchange relationship. Employees can trust their supervisor based on perceptions of benevolence, competence, and integrity, but that does not mean those leaders are going to take a risk on those employees. In order to grow and advance within an organization, employees need their leaders to take the risk by offering them greater control over outcomes in the workplace. Feeling trusted is necessary to grow and expand the social exchange relationship. This study, in addition to the group-level work of Salamon and Robinson (2008), demonstrates that felt trust has strong effects on the social exchange relationship between employees and their leaders. Future studies should test the effects of different leadership styles on the emergence of trust in leadership and felt trust.

The indirect effect of felt trust on turnover intention through felt obligation was not significant. This is surprising because it was expected that employees who are compelled to work for the goals of their supervisor are interested in remaining in that organization. One explanation could be that the measure of felt obligation in this study used the supervisor as the referent and turnover intention reflects attitudes held toward the organization. An employee could feel obligated to support their supervisor’s goals, but still perceive long-term employment in the organization unfavorably for a variety of other reasons. Similarly, previous research has demonstrated that trust in the CEO is more predictive of turnover intention than trust in supervisor (Costigan et al., 2011). Future research distinguishing felt obligation toward the supervisor and felt obligation toward the organization might help to clarify these relationships.

The relationship between trust perceptions and perceived autonomy and competence demonstrated several noteworthy outcomes. Felt trust strongly predicted perceptions of autonomy and provided an indirect effect for both engagement and turnover intention. Autonomous motivation is central to intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Gagné & Deci, 2005). Employees likely evaluate actions by their leaders to determine whether they are trusted to act and make decisions autonomously. Once they feel trusted, they are likely to experience autonomy. Future research examining the inclusion of felt trust as a mediator between leadership styles and employees’ perceived autonomy has several implications for organizational change processes and self-determination theory research. Employees might be given formal decisions latitude, but if they do not feel trusted, they might make decisions meant to mirror those that the leadership would have made instead of acting autonomously.

Unlike autonomy, the effects of trust on perceived competence were more complex. The indirect effect of felt trust through perceived competence predicted greater engagement and a greater intention to turnover. The results confirm the findings of previous research demonstrating that felt trust increases self-efficacy and perceived competence (Lau et al., 2014). Satisfying the need for competence is critical to experiencing intrinsic motivation on the job (Ryan & Deci, 2000). However, employees who feel highly competent because they are relied upon by their leaders are more likely to consider leaving the organization. Future studies should determine if career growth opportunities and promotion satisfaction moderate this relationship. The indirect effect of felt trust on turnover intention through competence could disappear when the employee feels there are adequate opportunities to keep advancing in the organization. Otherwise, they might feel more willing to risk leaving the organization in order to capitalize on their perceived market value (Maertz & Griffeth, 2004). The negative relationship between trust in supervisor and perceived competence was not expected. When employees are highly trusting of their leaders, they might be making social comparisons, causing them to be more critical of their own competence. Additionally, if employees consistently rely on the leaders’ judgments instead of their own, they might not experience their own sense of competence in the workplace. The use of an affect-based measure of trust (e.g., McAllister, 1995), as opposed to the reliance-based measure used in this study, might not demonstrate the negative relationship.

Limitations

Like all primary empirical research, this study is not without limitations. Most critical is the reliance on self-reported data for establishing the relationship between each of the constructs, which may impact the relationships due to common method bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, 2012). Several steps were taken to mitigate those risks. Responses were anonymous, which reduces evaluation apprehension; different response anchors were used for trust perceptions and the mediators; and both negative and positive valence items were presented at random (Chang, van Witteloostuijn, & Eden, 2010; Podsakoff et al., 2012). Additionally, we tested for common method variance by adding a method factor to the measurement model in which all items load on to their intended constructs and the method factor (see Hunter et al., 2013; Podsakoff et al., 2012; Williams, Cote, & Buckley, 1989). Model fit did not improve when a method factor was added to the measurement model.

Another limitation of the study is the use of cross-sectional correlational data. The use of a mediation model implies causation, but without experimental or cross-lagged data, the causal inferences that can be drawn are limited (Stone-Romero & Rosopa, 2004). Therefore, in order to provide further evidence regarding the validity of the causal order, we tested an alternative model switching the trust perceptions and mediators. The models demonstrated substantially worse fit. These findings, combined with the theoretical arguments behind our model, provide some support for the causal relationships proposed.

Our sample characteristics could potentially have some limitations for the generalizability of our results. External validity refers to the degree to which the results would appear the same if held at others times, with different participants, and in other settings (Cook, Campbell, & Day, 1979; Sackett & Larson, 1990). The main concern for convenience samples is range restriction and that a characteristic of the sample is driving the results (Landers & Behrend, 2015). With regard to range restriction and trust theories, samples from one organization could limit the variance in trust perceptions since trust can be influenced by the organizational politics or the interdependence of supervisor-subordinate relationships. Therefore, research collecting a more diverse sample from multiple workplaces has the advantage of diversifying the contexts of the supervisor-subordinate relationships and the level of trust.

Finally, we were concerned with sample differences between those collected through MTurk (40%) and the rest of the sample. Therefore, the mediation hypotheses between felt trust and the two outcome variables were retested within the subgroups of MTurk and non-MTurk, and nine out of the ten mediation tests were confirmed. The positive indirect effect of felt trust to turnover intention via perceived competence only researched significance in the non-MTurk sample. Taken as a whole, our further subsample tests address several limitations that arise from our sampling method.

Practical Implications

The results suggest that organizations concerned with improving trust within supervisor-subordinate relationships would be wise to measure and manage both trust in supervisor and felt trust among employees. Subordinates’ trust in their managers and leaders is critical to managing uncertainty and reducing turnover intention. However, it is important to also consider whether subordinates are also feeling trusted by their superiors. The results of this study, coupled with those of Salamon and Robinson (2008), demonstrate that employees who feel trusted will be motivated to rise to the occasion through greater responsibility and engagement on the job. Fostering felt trust might also be more important in industries that rely on bottom-up solutions and innovation from knowledge workers because maintaining their intrinsic motivation and willingness to take initiative are essential for leveraging knowledge resources (Uhl-Bien, Marion, & McKelvey, 2007). Therefore, measures specifically addressing felt trust could add substantial benefits for organizations seeking a more empowered and engaged workforce.

More research is needed to understand the mechanisms that foster felt trust. Rigid control systems and contingent agreements by definition are thought to hinder the development of trusting relationships (Mayer et al., 1995). For organizations seeking to develop more flatly distributed power structures and democratized decision-making, tracking levels of felt trust could be a key outcome variable to determine their progress. At the individual level, management 360 feedback could also incorporate both forms of trust. The results suggest that effective managers will need to be able to develop trust in subordinates and also make those subordinates feel trusted. Further research is needed to determine the most effective behaviors for enhancing felt trust.

Conclusion

We sought to provide a theoretical justification and empirical evidence for the importance of measuring both trust in supervisor and felt trust simultaneously when predicting employee motivation and outcomes. We proposed and demonstrated that each of the trust perceptions demonstrated unique relationships with employee outcomes based on different theoretical mediating pathways. Hypothesis testing generally supported the arguments that trust in supervisor reduces turnover intention via a reduction in workplace uncertainty when employees also felt trusted by those supervisors. Additionally, felt trust alone predicted engagement on the job through a deepening of the social exchange relationship (i.e., felt obligation) and increases in self-determination (i.e., perceived autonomy and competence). The findings suggest that felt trust has a central role in predicting workplace motivation which previous studies only measuring trust in supervisor may have missed. Therefore, consultants and organizations need to be aware that both the trust of employees toward their supervisors and employees’ feeling of being trusted are vital resources related to desirable employee outcomes.

References

Allen, D. G., Bryant, P. C., & Vardaman, J. M. (2010). Retaining talent: Replacing misconceptions with evidence-based strategies. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(2), 48–64. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMP.2010.51827775.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Brower, H. H., Lester, S. W., Korsgaard, M. a., & Dineen, B. R. (2009). A closer look at trust between managers and subordinates: Understanding the effects of both trusting and being trusted on subordinate outcomes. Journal of Management, 35, 327–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307312511.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393980.

Byrne, Z. S., Peters, J. M., & Weston, J. W. (2016). The struggle with employee engagement: Measures and construct clarification using five samples. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101, 1201–1227. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000124.

Cavanaugh, M. A., Boswell, W. R., Roehling, M. V., & Boudreau, J. W. (2000). An empirical examination of self-reported work stress among US managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.1.65.

Chang, S.-J., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the Editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41, 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88.

Chen, G., Kirkman, B. L., Kanfer, R., Allen, D., & Rosen, B. (2007). A multilevel study of leadership, empowerment, and performance in teams. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.331.

Clark, M. S., & Mills, J. (1979). Interpersonal attraction in exchange and communal relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.1.12.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., Piccolo, R. F., Zapata, C. P., & Rich, B. L. (2012). Explaining the justice–performance relationship: Trust as exchange deepener or trust as uncertainty reducer? Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025208.

Cook, T. D., Campbell, D. T., & Day, A. (1979). Quasi-experimentation: Design & analysis issues for field settings (Vol. 351). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Costigan, R. D., Insinga, R. C., Berman, J. J., Kranas, G., & Kureshov, V. A. (2011). Revisiting the relationship of supervisor trust and CEO trust to turnover intentions: A three-country comparative study. Journal of World Business, 46, 74–83.

Crawford, E. R., Lepine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 834–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019364.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602.

De Cremer, D., & Tyler, T. R. (2007). The effects of trust in authority and procedural fairness on cooperation. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 639–649. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.639.

Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030644.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627–668. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19, 109–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6.

Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., Gagne, M., Leone, D. R., Usunov, J., & Kornazheva, B. P. (2001). Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 930–942. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167201278002.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115.

Deng, J., & Wang, K. Y. (2009). Feeling trusted and loyalty: Modeling supervisor-subordinate interaction from the trustee perspective. International Employee Relations Review, 15, 16–38.

Dietz, G., & De Hartog, D. N. D. (2006). Measuring trust inside organisations. Personnel Review, 35, 557–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610682299.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2001). The role of trust in organizational settings. Organization Science, 12, 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.4.450.10640.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 611–628. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.4.611.

Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, P. D., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.1.42.

Eisenberger, R., & Stinglhamber, F. (2011). Perceived organizational support: Fostering enthusiastic and productive employees. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Ford, C. M., & Gioia, D. A. (2000). Factors influencing creativity in the domain of managerial decision making. Journal of Management, 26, 705–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600406.

Fulmer, C. a., & Gelfand, M. J. (2012). At what level (and in whom) we trust: Trust across multiple organizational levels. Journal of Management, 38, 1167–1230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312439327.

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322.

Gillespie, N. (2003). Measuring trust in working relationships: The behavioral trust inventory. In Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Seattle, WA. (pp. 1–56).

Gong, Y., Farh, J. L., & Chattopadhyay, P. (2012). Shared dialect group identity, leader–member exchange and self-disclosure in vertical dyads: Do members react similarly? Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 15(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2011.01359.x.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6, 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5.

Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26, 463–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600305.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

Heavey, A. L., Holwerda, J. A., & Hausknecht, J. P. (2013). Causes and consequences of collective turnover: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98, 412–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032380.

Hom, P. W., & Griffeth, R. W. (1991). Structural equations modeling test of a turnover theory: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.3.350.

Hunter, E. M., Neubert, M. J., Perry, S. J., Witt, L. A., Penney, L. M., & Weinberger, E. (2013). Servant leaders inspire servant followers: Antecedents and outcomes for employees and the organization. The Leadership Quarterly, 24, 316–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.12.001.

Jaros, S. J. (1997). An assessment of Meyer and Allen’s (1991) three-component model of organizational commitment and turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51, 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1995.1553.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287.

Kirkman, B. L., Lowe, K. B., & Young, D. P. (1999). High-performance work organizations: Definitions, practices, and an annotated bibliography. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Kisbu-Sakarya, Y., MacKinnon, D. P., & Miočević, M. (2014). The distribution of the product explains normal theory mediation confidence interval estimation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 49(3), 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.903162.

Korsgaard, M. A., Brower, H. H., & Lester, S. W. (2014). It isn’t always mutual: A critical review of dyadic trust. Journal of Management, 41, 47–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314547521.

Korsgaard, M. A., & Sapienza, H. J. (2002). Economic and non-economic mechanisms in interpersonal work relationships: Toward an integration of agency and procedural justice theories. In D. Steiner, D. Skarlicki, & S. Gilliland (Eds.), Research in social issues in management (Vol. 2, pp. 3–33). Greenwich, CT: IAP.

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 569–598. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.569.

Landers, R. N., & Behrend, T. S. (2015). An inconvenient truth: Arbitrary distinctions between organizational, mechanical Turk, and other convenience samples. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8, 142–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.13.

Lau, D. C., Lam, L. W., & Wen, S. S. (2014). Examining the effects of feeling trusted by supervisors in the workplace: A self-evaluative perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1861.

Lau, D. C., Liu, J., & Fu, P. P. (2007). Feeling trusted by business leaders in China: Antecedents and the mediating role of value congruence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24, 321–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-006-9026-z.

Lawler, E. J. (2001). An affect theory of social exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 107, 321–352. https://doi.org/10.1086/324071.

Lester, S. W., & Brower, H. H. (2003). In the eyes of the beholder: The relationship between subordinates’ felt trustworthiness and their work attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 10, 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190301000203.

Lewicki, R., McAllister, D., & Bies, R. (1998). Trust and distrust relationships and realities. Academy of Management Review, 23, 438–458. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1998.926620.

Lewis, J. D., & Weigert, A. J. (1985). Trust as a social reality. Social Forces, 91(1), 25–31.

Li, J. J., Lee, T. W., Mitchell, T. R., Hom, P. W., & Griffeth, R. W. (2016). The effects of proximal withdrawal states on job attitudes, job searching, intent to leave, and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101, 1436–1456. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000147.

Lind, E. A., & van den Bos, K. (2002). When fairness works: Toward a general theory of uncertainty management. Research in Organizational Behavior, 24, 181–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(02)24006-X.

Liu, D., Zhang, S., Wang, L., & Lee, T. W. (2011). The effects of autonomy and empowerment on employee turnover: Test of a multilevel model in teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 1305–1316. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024518.

Luhmann, N. (1979). Trust and power: Two works by Niklas Luhmann. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4.

Maertz, C. P., & Griffeth, R. W. (2004). Eight motivational forces and voluntary turnover: A theoretical synthesis with implications for research. Journal of Management, 30, 667–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jm.2004.04.001.

Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (1999). The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.1.123.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1995.9508080335.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 24–59. https://doi.org/10.2307/256727.

McEvily, B., & Tortoriello, M. (2011). Measuring trust in organisational research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Trust Research, 1, 23–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/21515581.2011.552424.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z.

Mishra, A. K., & Spreitzer, G. M. (1998). Explaining how survivors respond to downsizing: The roles of trust, empowerment, justice, and work redesign. Academy of Management Review, 23, 567–588. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.926627.

Mislin, A. A., Campagna, R. L., & Bottom, W. P. (2011). After the deal: Talk, trust building and the implementation of negotiated agreements. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.01.002.

Molm, L. D., Takahashi, N., & Peterson, G. (2000). Risk and trust in social exchange: An experimental test of a classical proposition. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 1396–1427. https://doi.org/10.1086/210434.

Mone, E., Eisinger, C., Guggenheim, K., Price, B., & Stine, C. (2011). Performance management at the wheel: Driving employee engagement in organizations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26, 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9222-9.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2008). Mplus (Version 5.1). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

O’Donnell, M., Yukl, G., & Taber, T. (2012). Leader behavior and LMX: A constructive replication. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27, 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941211199545.

Paolacci, G., Chandler, J., & Ipeirotis, P. G. (2010). Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5(5), 411–419 Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1626226.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.