Abstract

Although the topic of value congruence has attracted considerable attention from researchers and practitioners, evidence for the link between person–supervisor value congruence and followers’ reactions is less robust than often assumed. This study addresses three central issues in our understanding of person–supervisor value congruence (a) by assessing the impact of objective person–supervisor value congruence rather than subjective value congruence, (b) by examining the differential effects of value congruence in strongly versus moderately held values, and (c) by exploring perceived empowerment as a central mediating mechanism. Results of a multi-source study comprising 116 person–supervisor dyads reveal that objective value congruence relates to followers’ job satisfaction and affective commitment and that this link can be explained by followers’ perceived empowerment. Moreover, polynomial regression and response surface analyses reveal that congruence effects vary with the importance that leaders and followers ascribe to a certain value: Congruency in strongly held values have more robust relations with followers’ outcomes than congruence in moderately held values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The study of value congruence is one of the oldest and most enduring topics in organizational research (Edwards 2008; Schneider 2001). Values show us what we should do or not do, and we refer to values when justifying the legitimacy of our behavior (Roccas et al. 2002). Values include tendencies for promoting safety and stability, for tolerance, and for protection of the welfare of others (Schwartz et al. 2012). As guiding principles for what is right and wrong, values are a central topic in organizational studies and in the domain of business ethics (Joyner and Payne 2002). Values are individuals’ moral compasses that guide people’s decisions and interactions in their social and work environment (Fritzsche and Oz 2007; Van Quaquebeke et al. 2014). When people experience value congruence at work, they feel trust toward their organization and are more motivated (Posner 2010; Schuh et al. 2015). An extensive volume of research has linked value congruence to favorable followers’ outcomes (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). One aspect in the study of values that has attracted considerable attention is the interplay between leaders’ and followers’ values (e.g., Hayibor et al. 2011; Meglino et al. 1989; Ogunfowora 2014). Indeed, studies suggest that when leaders’ and followers’ values are congruent, followers find their work more satisfying and they are more committed to their organizations (see also Kemelgor 1982; Van Vianen et al. 2011).

Despite considerable progress in understanding the effects of value congruence between leaders and followers, important points have remained open for further investigation. First, a thorough review of the existing literature suggests that the evidence for person–supervisor value congruence is less solid than often assumed and has produced mixed effects. Whereas some studies have found significant relations of person–supervisor value congruence and favorable followers’ outcomes (e.g., Meglino et al. 1989), other studies did not reveal such links (e.g., Hayibor et al. 2011). These mixed results are puzzling and may be due to several methodological issues (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). Indeed, existing studies have largely relied on subjective measures of value congruence as reported by the follower. However, such measures are prone to perceptual and motivational distortions such as dynamics of cognitive dissonance (Erdogan et al. 2004). As Hewlin et al. (2017) indicated, employees may pretend to perceive a fit, even when this is not the case. Moreover, these studies have often analyzed person–supervisor value congruence based on difference scores (e.g., Ashkanasy and O’Connor 1997; Meglino et al. 1989). However, difference scores are seen as problematic indicators as they may lead to inaccurate results regarding congruence effects—for example, due to their low reliabilities and issues of discarded information (Edwards 1993).

Second, to date the literature on person–supervisor value congruence has paid little attention to important differential effects that may be inherent to value congruence. Specifically, extant research largely assumes that congruence in different values is equally important—no matter whether leaders and followers hold extreme or moderate views on these values. For example, some people may see stability as extremely important or as extremely unimportant, whereas other people may assume that stability is of moderate relevance. Yet, current congruence theory does not distinguish between value congruence in strongly versus moderately held values (Hayibor et al. 2011). Indeed, existing theory assumes that value congruence is equally beneficial—no matter whether it exists in strongly versus moderately held values. As Edwards (2008) pointed out, overlooking such nuances and differential effects of congruence may be a central barrier to further developing value congruence models. Moreover, treating extreme and moderate values as equally important for value congruence is puzzling—it contradicts fundamental insights from the field of social psychology that extreme beliefs generally have a stronger effect on people’s affect and behavior than moderate ones (Krosnick and Smith 1994).

Third, as the notion of person–supervisor value congruence evolves, it is important to understand why person–supervisor value congruence affects followers’ reactions. Unfortunately, previous research has largely ignored the psychological mechanisms and little is known about the underlying processes of person–supervisor value congruence. Understanding such mediating dynamics is desirable from a conceptual standpoint to further enhance congruence theory but also from a practical perspective—as it may indicate important levers for practical interventions.

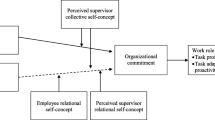

Against this backdrop, this study seeks to contribute to a better understanding of person–supervisor value congruence in the following ways: First, rather than relying on subjective measures of person–supervisor value congruence, we examine to which extent actual person–supervisor value congruence, based on leaders’ and followers’ ratings, relates to favorable employee outcomes. In doing so, we apply polynomial regression and response surface methodologies, which allow for a more accurate analysis of potential congruence effects. We are not aware of any research that has examined objective person–supervisor value congruence using polynomial regression. Second, we develop and test the notion that congruence in values on which leaders and followers hold extreme views may be related more strongly to followers’ outcomes than congruence in values on which leaders and followers have moderate views. We develop this perspective by reconciling value congruence theory with central insights from social psychological research. Third, we seek to shed light on how person–supervisor value congruence effects are related to followers’ outcomes. Specifically, given that holding similar convictions facilitates perspective-taking as well as mutual appreciation and motivation (Meglino et al. 1989; Suazo et al. 2005), we develop and test the argument that followers’ perceived empowerment is a central mechanism that links person–supervisor value congruence and followers’ reactions. Figure 1 shows our theoretical model.

Person–Supervisor Value Congruence

Values are influential and universal manifestations in the lives of individuals, groups, organizations, and cultures (e.g., Rokeach 1973; Lord and Brown 2001; Cha and Edmondson 2006). Rokeach (1973) described values as “enduring beliefs that a specific mode of conduct is personally or socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end state of existence” (p. 5.). Similarly, Schwartz (1996) defined values as “desirable, trans-situational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in the life of a person or other social entity” (p. 21). Values affect human life by indicating desirable outcomes and by influencing individuals’ attitudes in various life contexts, including work situations (Bardi and Schwartz 2003).

In organizational context, value research has paid strong attention to the notion of value congruence—the extent to which employees hold similar beliefs as their social environment (Edwards 2008). Person–supervisor value congruence is defined as the similarity between the value system of the leader and his or her follower and is supposed to positively affect followers’ attitudes and behaviors (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005). Indeed, similarity is seen to lead to positive sentiments and liking, whereas dissimilarity can engender negative emotions and even repulsion (Byrne 1971). This should particularly hold true for similarity in values, as values are a fundamental aspect of a person’s identity (Edwards and Cable 2009; Schwartz 1992). Accordingly, studies have explored the effect of person–supervisor value congruence. For instance, Kemelgor (1982) in an early study found that similar values between leaders and followers relate to higher job satisfaction, Van Vianen et al. (2011) indicated the link between person-supervisor value congruence and organizational commitment, and Hayibor et al. (2011) have shown that value congruence is important in the process through which leadership styles influence employees.

However, the value congruence literature has most often analyzed person–organization value congruence or followers’ perceptions of congruence but not the actual congruence between leaders’ and followers’ values (e.g., Gregory et al. 2010; Jung and Avolio 2000; Van Vianen et al. 2011). This is surprising as subjective value congruence can be affected by multiple cognitive factors that may bias perceptions of congruence (Ravlin and Ritchie 2006). For example, according to self-perception theory (Bem 1967) and cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger 1957) individuals try to maintain consistency. Followers who experience low value congruence with their leader may struggle with cognitive dissonance (Erdogan et al. 2004). It is thus likely that followers induce cognitive manipulation and report perceived value congruence even when this is not the case (Edwards 1993; Hewlin et al. 2017). Value perception allows individuals to apply their own subjective assessment, which can result in common rater bias (like social desirability response, Crowne and Marlowe 1960). For example, because of personality factors or leadership influence, followers may have mistaken beliefs about the value congruence with their leaders. That again can lead to artificial covariance due to consistency biases and illusory correlations (Edwards 1993; Van Vianen et al. 2011). These processes underscore the importance of measuring value congruence objectively (i.e., based on separate measures of leaders and followers).

Congruence Effects and the Mediating Role of Empowerment

Besides examining the relationship between similar values on outcomes, we expect that person–supervisor value congruence will relate directly to affective commitment and job satisfaction and indirectly through followers’ perceived empowerment. Menon (1999) describes empowerment as a set of people’s perceptions about them shaped by their work environment, particularly by their leader. Specifically, empowerment is defined as a cognitive state characterized by self-determined work, chance of independent decision making, perceived competence, coping with unexpected situations and challenges and the availability of resources (Menon 1999). Spreitzer (1995) indicated: “Widespread interest in empowerment comes at a time when global competition and organizational change have stimulated a need for employees who can take imitative, embrace risk, stimulate innovation, and cope with high uncertainty.” In other words: “Focusing only on work related outcomes may not be sufficient anymore. There is a need to better understand the processes by which desirable personal outcomes of employees can be enhanced” (Krishnan 2012, p. 550).

We expect that value congruence between leaders and followers is positively related to followers’ empowerment: First, similarity in values fosters a better understanding between leaders and followers (Suazo et al. 2005). When leaders and followers hold similar ideals, they are better equipped to predict the behavior of their counterpart (Meglino et al. 1989), they experience fewer misunderstandings (Graen and Scandura 1987), and they have more positive communication (Dulebohn et al. 2012). These processes, in turn, should foster followers’ perceived empowerment because followers may feel understood and appreciated by their leader and because the leader may provide more resources. Second, by definition, values are representations of motivational goals (Schwartz 1992). As empowerment is described as an increased task motivation (Spreitzer 1995), holding similar motivational goals may positively relate to followers’ task motivation. Specifically, value similarity reduces the likelihood of interpersonal frictions often associated with divergent goals and motivations (Meglino et al. 1989). Conversely, holding different values involves a need to discuss or compromise one’s convictions. Both should hamper with the development of an increased followers’ empowerment. Finally, as noted earlier, similarity fosters positive perceptions of the other party, including attributions of competence and benevolence (Turban and Jones 1988). Thus, leaders may provide more responsible and challenging work tasks for followers with similar values. The higher responsibility again should foster followers’ perception about their competence, impact, self-determination and meaning of their job which can be summarized as followers’ perceived empowerment (Spreitzer 1995). In sum, we expect that value congruence facilitates perspective-taking, mutual appreciation, and goal motivation and, consequently, fosters followers’ perceived empowerment. Thus, we predict:

Hypothesis 1

Person–supervisor value congruence is positively related to followers’ perceived empowerment.

Furthermore, perceived empowerment is one of the most important factors to influence followers’ work attitudes (Gregory et al. 2010; Spreitzer 1995). As perceived empowerment is described as a series of cognitions that shape intrinsic motivation (Thomas and Velthouse 1990), it is conceivably that followers who perceive empowerment find their job more meaningful, feel powerful in their work environment, and are therefore more enthused to fulfill their job successfully (Seibert et al. 2011). Indeed, higher followers’ perceived empowerment has been shown to relate positively to followers’ work attitudes like job satisfaction and commitment (Liden et al. 2000; Seibert et al. 2011; Spreitzer 1995). These empirical findings suggest that followers are more committed to their organization and experience higher levels of job satisfaction, when they have a feeling of competence, can work independently, and know that their work is a meaningful contribution to their organization (Gregory et al. 2010). Therefore, we predict that similar values between followers and their leaders will not only relate to followers’ perceived empowerment, but also that followers’ perceived empowerment mediates the relation between person–supervisor value congruence and affective commitment and job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2

Followers’ perceived empowerment mediates the relation between person–supervisor value congruence and (a) affective commitment and (b) job satisfaction.

Moderate Versus Extreme Values: Differential Congruence Effects

In order to understand the effect of value congruence more thoroughly, it appears crucial to analyze person-supervisor value congruence for which leaders and followers hold extreme sentiments (degree of favorability). Former research has largely overlooked the possibility that congruence in values on which leaders and followers hold strong beliefs (e.g., which they regard as extremely important or extremely unimportant) may relate stronger to followers’ outcomes than congruence on values on which leaders and followers have only moderate views (Edwards 2008). This is despite evidence from fundamental research that the link between people’s values and actions is not as straightforward as often assumed and that value extremity is a central predictor for whether people will act in accordance with their values (Krosnick and Smith 1994). For instance, prior studies have shown that people with extreme attitudes are more likely to speak up in an effort to persuade those who disagree with them (Baldassare and Katz 1996; Binder et al. 2009). Moreover, Taber and Lodge (2006) found that people with strong attitudes became even more extreme in their views when presented with supporting and contradicting arguments. This was because they accepted congruent evidence rather uncritically but strongly devaluated incongruent information.

Hence, extreme values seem to have stronger influence on people’s reaction than moderate attitudes (Krosnick and Smith 1994). This is because extreme beliefs have stronger influence on cognitive processes and behavior (Sherif and Hovland 1980; Krosnick and Petty 1995). Individuals with extreme beliefs have a large amount of information about the specific belief object available and evaluate other people more on their belief similarity than people with moderate beliefs. Because of the similarity-attraction effect, people with similar beliefs are seen as more attractive than people with contrary beliefs, which then leads to better interpersonal relationships (Krosnick and Smith 1994). In a similar vein, principles of cognitive consistency suggest that similarity in attitudes should result in more positive interaction (Byrne 1971). As people with extreme attitudes attach higher importance to attitude similarity, this seems to be particularly true for congruence in strongly held values as compared to moderate ones (Krosnick and Smith 1994).

Thus, we expect that congruence in values for which leaders and followers hold extreme sentiments will relate more strongly to followers’ reactions than similarity in moderate values (a curvilinear effect). That is, because values, leaders and supervisors strongly agree or disagree with, may be seen as more important than moderate beliefs. Leaders and followers have gathered more information about those important values and consequently form a strong negative or positive opinion toward them. Drawing from findings on attitude extremity, leaders and followers than seem to pay more attention toward similarity with others in those extreme values (Krosnick and Smith 1994). Thus, we predict:

Hypothesis 3

Objective person–supervisor value congruence on a high and low level is more strongly related to (a) followers’ perceived empowerment, (b) followers’ affective commitment, and (c) followers’ job satisfaction than objective person–supervisor value congruence on a moderate level.

Method

Participants and Procedures

To reach a broad spectrum of the working population, we contacted the human resource departments of 58 different organizations in Germany to take part in this study. The human resource departments invited in total 301 leader–follower dyads to participate. Every leader and follower received the survey separately with a pre-stamped envelope addressed to the principal researchers’ university, to ensure that no unauthorized person could see their responses. We received complete data from 116 person–supervisor dyads from various sectors, mainly from media (18%), services (15%), and trade (13%). Sixty percent of the participating leaders were male with an average age of 41.92 years (SD = 9.57). They had worked in leadership positions for on average 11.01 years (SD = 9.31) and supervised 13.70 employees (SD = 18.55). The average age of followers was 31.25 years (SD = 8.41) and 39% was male. Their tenure with leaders was 4.60 years (SD = 5.80), and their tenure in the organization equaled 5.83 years (SD = 7.14).Footnote 1

Measures

Leaders’ and Followers’ Values

We measured leaders’ and followers’ values using a 29-item German version of the Portrait Value Questionnaire (PVQ; Schwartz 1992; German version by Schmidt et al. 2007). This survey assesses the four universal value dimensions defined by Schwartz (1992) (self-enhancement, self-transcendence, conservation, and openness to change). Previous studies have assessed these value dimensions in the work context and have shown their relevance (e.g., Brown and Treviño 2006; Edwards and Cable 2009).

The PVQ presents participants with short description of different people. Each of these descriptions involves a personal goal, aspiration, or wish that point implicitly to the importance of a single-value dimension (Schwartz and Bardi 2001). Example items are: “It is important to him/her to show his/her abilities. S/he wants people to admire what s/he does” (self-enhancement); “S/he thinks it is important that every person in the world should be treated equally” (self-transcendence); “It is important to him/her that things be organized and clean. S/he doesn’t want things to be a mess” (conservation); “Thinking up new ideas and being creative is important to him/her. S/he likes to do things in his/her own original way” (openness to change). Participants rated these statements on six-point scales—this person is… 1 = not like me at all, 6 = very much like me. The reliabilities for employees and supervisors were .89 and .90 for self-enhancement, .82 and .83 for self-transcendence, .68 and .73 for conservation, and .74 and .67 for openness to change, respectively. The reliabilities of two of our scales were slightly below .70 (.68 for employee conservation and .67 for supervisor openness). However, these scores were close to .70, and previous studies had reported similar reliabilities (e.g., Feather 2004; Schmidt et al. 2007). Hence, we believe that these reliabilities may not be a severe problem in the present context.

Followers’ Empowerment

We measured followers’ perception of empowerment with 10 items by Menon (1999). To ensure translation equivalence, all items were translated into German and back-translated into English by two bilingual researchers (Brislin 1970). While one researcher worked on the initial translation, the other researcher did the back-translation. We could only find minor variations when comparing the original and the back-translation. Those were resolved through discussion. Example items include “I can influence the way work is done in my department” and “I have the authority to make decisions at work” (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree; α = .86).

Affective Commitment

We assessed followers’ affective organizational commitment with the nine-item German version of the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ) by Maier and Woschée (2002). An example item is: “I would accept almost any type of job assignment in order to keep working for this company” and “I am proud to tell others that I am part of this organization” (1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree; α = .93).

Job Satisfaction

We measured followers’ job satisfaction with the eight-item scale by Neuberger and Allerbeck (1978). An example item is: “How satisfied are you with your colleagues?” We applied a five-point scale, anchored by a smiling and frowning face scale (Kunin 1955; see also Kristof-Brown et al. 2002;. α = .90).

Polynomial Regression with Response Surface Analysis

To test the proposed congruence effects, we applied polynomial regression with response surface analysis. The response surface methodology combined with polynomial regression offers a deeper look into the relation of two predictor variables and an outcome variable (Edwards 2002). By using this analysis, we are able to study our proposed model in a three-dimensional space and can explore the proposed relations from different angles (Edwards and Parry 1993). This approach has several advantages compared to the traditional use of difference scores (Edwards 2002; Shanock et al. 2010): First, it avoids difficulties with extenuated reliability produced when two variables are subtracted from each other. Second, polynomial regression analysis shows independent effects of single components and allows for analyzing the degree to which each predictor contributes to variance in the outcome variable. Third, response surface analysis enables plotting the results in a three-dimensional graph and hence offers a new perception of the relationship between the two predictor variables and the outcome variable. This three-dimensional presentation makes it possible to study the degree of discrepancy and the combined effect on the outcome variable in more detail.

The basic equation for polynomial regression analysis is: Z = b0 + b1X + b2Y + b3X2 + b4XY + b5Y2 + e. Z is the dependent variable (e.g., affective commitment), X the first predictor (in our case supervisors’ values), and Y the second predictor (in our case employees’ values). Besides the two predictors X and Y, their higher-order terms X2, XY, Y2 were entered into the analysis. We constructed the response surface patterns and interpreted the results of the four surface test values a1–a4 (Edwards 2002). In the surface chart, the line of congruence depicts perfect agreement between the two predictor variables (e.g., value congruence) in relation to the outcome variable (e.g., affective commitment). The line of incongruence runs perpendicular to the line of congruence and captures how the degree of discrepancy between the predictor variables may affect the outcome variable. The test values a1–a4 represent the response surface in numerical terms. Specifically, the value a1 and a2 represent the slope and curvature of the congruence line, and the test values a3 and a4 represent the slope and curvature of the incongruence line. Mathematically, a1–a4 are calculated by adding and subtracting the regression coefficients of the polynomial regression equation. a1 equals b1 + b2 (b1 is the regression coefficient for leader values and b2 is the regression coefficient for followers’ values). a2 equals b3 + b4 + b5 (b3 is the regression coefficient for leader values squared, b4 is the regression coefficient for the product of leaders’ values and followers’ values, and b5 is the regression coefficient for followers’ values squared). Lastly, a3 equals b1–b2 and a4 equals b3–b4 + b5 (Edwards 2002). Following the recommendation by Edwards (1994), we mean-centered the predictor variables prior to analysis. Figure 2 shows an example for perfect fit.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics, reliability scores, and inter-correlations.

Test of Hypotheses

Table 2 presents the results of the polynomial regression analyses and the coefficients of the response surfaces (i.e., of the slopes and curvatures along the congruence and incongruence lines).

Hypothesis 1 predicted a congruence effect of leaders’ and followers’ values on empowerment. As listed in Table 2 and in line with Edwards (1994), jointly adding the three second-order polynomial terms (the quadratic term of leader values, the quadratic term of followers’ values, and the product of leaders’ and followers’ values) resulted in a significant increase in the explained variance for all four values (ΔR2 reached from .10 to .13; F reached from 2.94 to 4.16; p < .05). The related surface charts are shown in Fig. 3. In order to test the congruence effect, we have to analyze the slope of the incongruence line (Edwards 1994). As shown in Fig. 3 and in line with our hypotheses, the shape of the response surface followed an inverted U-shape along the incongruence line (i.e., a downward-curved, concave surface). Relatedly, as listed in Table 2, the curvature was negative for all four value dimensions—as indicated by the a4 value). Moreover, this a4 value was significant for self-enhancement (a4 = − .22, p < .01). Hence, the pattern of results provides general support for Hypothesis 1 with regard to empowerment. It is important to note that for the interpretation of the polynomial regression results, main emphasis is often placed on the shape of the surface chart—i.e., whether the surface generally supports the predicted relationships. For example, as Kristof-Brown and Stevens (2001) noted, in polynomial regression “less emphasis is typically placed on the significance of specific regression weights than on the variance explained by the set of predictor variables and the surface pattern yield by the regression equation” (p. 1087; see also Voss et al. 2006).

Hypothesis 2 predicted that the relationship between leader–follower value congruence and affective commitment and job satisfaction was mediated by empowerment. Before we examined this hypothesis, we tested whether leader–follower value congruence also had a total effect on the two outcome variables (i.e., affective commitment and job satisfaction). Even though this total effect is not necessarily a requirement for mediation (MacKinnon et al. 2002), we believe that this analysis can provide additional confidence in our theoretical model. For affective commitment, the three second-order polynomial terms were also jointly significant for self-transcendence, self-enhancement, and conservation value variables (F ranged from 2.73 to 4.32; all p < .05). As shown in Fig. 4, we found again a negative curvature along the incongruence line (X = − Y) for all value dimensions. Moreover, as listed in Table 2, the coefficients for self-transcendence and self-enhancement values were significant (a4 = − .86, p < .01; a4 = − .29, p < .03). In a similar vein, for job satisfaction, we found again a negative curvature along the incongruence line (X = − Y) for all values, as shown in Fig. 5. In addition, as listed in Table 2, self-transcendence and openness to change values differed significantly from zero (a4 = − 1.05, p < .01; a4 = − 1.50, p < .01). In sum, these findings suggest that affective commitment and job satisfaction generally increased when leaders’ and followers’ values became more similar.

In a next step, to test our mediation hypotheses, we created block variables as advocated by Edwards and Cables (2009). This approach allows obtaining a single coefficient for each path in a mediated value congruence model. Specifically, a block variable is “a weighted linear composite of the variables that constitute the block, in which the weights are the estimate regression coefficients for the variables in the block” (Edwards and Cable 2009, p. 660). Results showed that the path linking supervisor and subordinate values to empowerment was significant for all four value dimensions (conservation: .36, p < .001; openness to change: .34, p < .001; self-transcendence: .40, p < .001; self-enhancement: .37, p < .001, see Table 3). Then, we examined the paths between empowerment and the outcomes. To this end, and following Edwards and Cable (2009), we regressed affective commitment and job satisfaction on empowerment while controlling for the terms representing supervisors’ and followers’ values (i.e., X, Y, X2, XY, Y2). This path was significant for both outcomes (affective commitment and job satisfaction) and all four value dimensions (path coefficients ranged from .60 to .76; all p < .01; see Table 3). These coefficients were then used to calculate the indirect effects transmitted through empowerment in our mediation analysis. We calculated bootstrap confidence intervals to test the indirect effects (Edwards 2002). The results show that empowerment mediated the combined effects of leaders’ and followers’ value congruence on followers’ affective commitment and job satisfaction (path coefficients ranged from .21 to .28; all p < .05; see Table 3). Taken together, these results provide support for Hypothesis 2.

Finally, Hypothesis 3 predicted that empowerment, affective commitment, and job satisfaction increase more sharply when value congruence exists for either high or low rated values rather than for moderately rated values. In other words, we predicted a curvature along the congruence line (X = Y). As shown in Figs. 3, 4, and 5, the shape of all surface charts followed an inverted U-shape along the congruence line. Moreover, the related coefficient a2 was positive for all value–outcome relations also indicating an inverted U-shape along the congruence line. Eight of these coefficients were statistically significant (see Table 2 and Figs. 3, 4, and 5 for visualizations). In sum, this indicates that empowerment, affective commitment, and job satisfaction increased more strongly when leaders and followers agreed that a specific value is very important or very unimportant, respectively, than when they agreed that a value is of moderate relevance. This finding provides support for Hypothesis 3.

Discussion

Person–supervisor congruence has been an important line of research in the leadership and ethics studies (e.g., Brown and Treviño 2006; Kristof-Brown et al. 2005; Kim and Kim 2013). With the present study, we aimed to provide three important extensions to these fields by focusing on objective value congruence, by testing the impact of values at different levels of importance, and by analyzing a central mediating process. In line with our hypotheses, results showed that objective person–supervisor value congruence related to followers’ perception of empowerment, which, in turn, was linked to followers’ affective commitment and satisfaction with their jobs. However, the strength of these person–supervisor congruence effects was not linear. Indeed, it varied as a function of the importance that leaders and followers ascribed to a certain value. Congruence in values that leaders and followers rate as extremely important or extremely unimportant relates more strongly to followers’ attitudes than congruence on moderate values. These findings are relevant for theory and practice.

Theoretical Implications

First, our findings indicate that value congruence between leaders and followers does indeed matter and does relate to important followers’ outcomes. This finding is relevant because the mixed findings in previous studies have casted some doubt on the existence of person–supervisor value congruence effects (Hayibor et al. 2011). In the present study, by using polynomial regression with response surface analyses, we were able to overcome several issues that may have affected previous studies. Moreover, by measuring leaders’ values and followers’ values separately, we could avoid several problems that may be inherent in subjective measures of value congruence—e.g., influences self-perception and cognitive dissonance (Erdogan et al. 2004; Hewlin et al. 2017). In sum, this is an important finding because it reaffirms the notion of person–supervisor value congruence using robust methodological approaches. We believe that polynomial regression and response surface analyses can also be beneficial for areas beyond person–supervisor value congruence. For example, these analyses may be useful to examine similarities between leader–follower affect (e.g., Cropanzano et al. 2017), attachment styles (Hinojosa et al. 2014), and humor (Wisse and Rietzschel 2014), and to analyze similarities between colleagues in teams (Walter and Bruch, 2008). Besides showing the importance of person–supervisor value congruence in general, our findings also indicate stronger congruence effects on the self-transcendence dimension than on the other three value dimensions. Although we did not expect this differential effect, it may point toward another important extension of theorizing on person–supervisor value congruence, which generally assumes that “similarity on values is […] universally desirable” (Kristof-Brown et al. 2005, p. 290). Indeed, the stronger relations of self-transcendence are consistent with an argument that self-transcendence is a particularly crucial and impactful dimension—because this value meets universal needs like fairness and social acceptance (Abbott et al. 2005; Finegan 2000). Relatedly, self-transcendence values have often been rated as more important than other values (Schwartz and Bardi 2001) and seem to foster leadership effectiveness more strongly than other value dimensions (Qu et al. 2017).

Second, our study also advances our theoretical understanding of person–supervisor fit. Specifically, although researchers have called for a more nuanced perspective on effects of congruency (Edwards 2008), extant research has largely overlooked the role of value extremity on congruence effects. However, as the present findings indicate, value congruence effects may not be uniform but are contingent on the importance that leaders and followers ascribe to a value dimension. This finding is consistent with fundamental notions of social psychological research, which state that extreme attitudes are more powerful than moderate attitudes (Krosnick and Smith 1994). More importantly, it challenges a central tenet of congruence theory, which traditionally predicts that the effects of congruence are the same regardless of whether congruence emerges at low, medium, or high levels (Edwards and Cable 2009). The pivotal role of extremity in person–supervisor congruence is further underscored when considering the results of several past studies (e.g., Meyer et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2012). Even though the authors did not predict nor discuss these results, an inspection of the congruence effects in these studies also show that congruence at very high or very low levels has stronger effects on important dependent variables. For example, Zhang et al. (2012) analyzed the congruence effect of leader personality on leader–member exchange (LMX). While they found the proposed congruence effect, their results also show a significantly curved surface along the congruence line. In other words, congruence in extreme personalities relates more strongly to LMX than congruence in moderate personalities. Thus, we believe that incorporating the notion of extremity in accounts of person–supervisor fit is an important step in advancing theorizing in this field.

Third, we also examined the process through which person–supervisor value congruence is linked to organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Our findings indicated that empowerment is a central variable in these relationships. This finding is important as proposing and testing mediating effects is crucial for further theory development. Even though conceptual work has suggested that employees fit with the work environment may contribute to perceptions of empowerment (Gregory et al. 2010), the relationship between person–supervisor value congruence and empowerment has barely been examined in empirical work. This is surprising, as fit, especially shared values, play a central role in triggering followers’ work motivation (Meglino et al. 1989). We believe that integrating empowerment and value congruence studies offers important insights into why person–supervisor value congruence is associated with key employee outcomes.

Practical Implications

Besides their theoretical implications, our findings also offer important insights for practice. First, they suggest that organizations may benefit from educating their leaders about the importance of value congruence with their followers. Human resources newsletters, video modules, or even one-on-one coaching may provide effective ways to do so (Ely et al. 2010). These programs should inform leaders about the pivotal role of value congruence at extreme levels and about the significance of self-transcendence values. The importance of self-transcendence values may also be interesting in view of person–organization value congruence. Indeed, Schein (2010) indicated that some values may be more important for employees than others—partly because these values directly reflect desirable aspects of the organization that are crucial for the organization’s identity. Thus, organizations may seek emphasize their views on self-transcendence values through HR marketing to be attractive for future employees and to promote a better person–organization fit (Fischer 2014).

However, achieving person–supervisor value congruence may not always be easy. For example, organizations increasingly strive to become inclusive and diverse and value congruence is only one consideration when organizations select employees (Bowen et al. 1991). Hence, if value congruence is difficult to achieve, organizations may seek to directly address employees’ sense of empowerment. As our results indicate, followers’ perceived empowerment transmits value congruence effects and hence may be a promising starting point for interventions if value congruence is low. Indeed, as congruence researchers have pointed out, addressing the mediating mechanism can be an effective way to compensate for low congruence (Edwards and Cable 2009). Prior research has identified several effective measures for leaders to empower their followers. For example, leaders can share authority through the use of managerial practices and techniques such as sharing necessary skills and knowledge (Srivastava et al. 2006), delegation of work tasks (Kirkman and Rosen 1999), and delineating the importance of followers’ work (Zhang and Bartol 2010). Furthermore, leaders should integrate followers in decision making, try to remove difficulties to perform and boosting followers’ confidence regarding their abilities and skills (Ahearne et al. 2005).

For future research, it would also be interesting to examine potential boundary conditions for the proposed effects of congruence in extreme values. For example, some organizations may see moderate levels of a certain value dimension as desirable (e.g., on the dimension of openness to change). Hence, in these organizations, person–organization fit may be highest if employees have a moderate level of this value. Consequently, in these organizations, person–supervisor fit effects may also be strongest when supervisors and employees are similar on a moderate level of this value dimension (rather than on low or high levels). We believe that this would be an important and interesting area for future studies.

Limitations

Like all research, this study has several limitations. First, we applied a cross-sectional design, which precludes us from making causal inferences. However, the notion that value congruence predominantly influences subsequent employee reactions is consistent with theory and prior research (Gabriel et al. 2013). Nevertheless, it would be desirable for future research to apply longitudinal or experimental designs.

Second and interestingly, the congruence relations were more pronounced for some value dimensions than for others. Specifically, as noted above, congruence on the self-transcendence dimension was more strongly related to affective commitment and job satisfaction than congruencies on the other three value dimensions. This may be explained by the higher importance of the self-transcendence value dimension. Self-transcendence values typically receive higher rating than other value dimensions (Schwartz and Bardi 2001) and are described as universally accepted and favored (House et al., 2004). Based on our findings, it may be interesting for future research to further explore the differential effects of different value dimensions for value congruence and to pinpoint exactly why these differential effects exist.

Third, albeit an important form of fit, PS fit is only one kind of fit in an organization (Kiristof-Brown et al. 2005). For example, employee relations at work do not only include the supervisor but also other members in the team. It would hence be interesting to examine potential combined or interactive effects between PS fit and person–team fit. Moreover, leaders typically have several subordinates and may thus have higher value congruence with some employees than with others. It may be interesting to examine the effects of these different levels of congruence. For example, previous studies suggest that differentiation within teams (such as LMX differentiation) may be related to lower team performance and/or higher turnover (Nishii and Mayer 2009; Henderson et al. 2008). However, it is unclear whether the same effects would emerge for differentiation in value congruence or whether differentiation in value congruence may, for instance, be related to positive effects such as deeper information processing among team members (e.g., De Dreu 2007). Testing such effects may be an interesting avenue for future studies.

Conclusion

Person–supervisor value congruence is a fascinating field of study that offers important insights into the dynamics between leaders and followers. Our findings identify objective person–supervisor value congruence as a central factor for followers’ outcomes, followers’ empowerment as a mediating mechanism, and the pivotal role of value extremity. We believe that the findings of this study offer important extensions that can advance both theory development and practical interventions in the fields of value research and business ethics.

Notes

The data presented in this manuscript were part of a larger data collection effort. A first paper has recently been accepted for publication by the Journal of Organizational Behavior. The current manuscript is the second and last paper from this database. Importantly, the published paper and the current manuscript do not overlap in any of the used variables. To keep the review process anonymous, we had to withhold the exact reference of the published paper. However, it is known to the Editor of the Journal of Business Ethics.

References

Abbott, G. N., White, F. A., & Charles, M. A. (2005). Linking values and organizational commitment: A correlational and experimental investigation in two organizations. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78(4), 531–551. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26174.

Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J., & Rapp, A. (2005). To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behaviour on customer satisfaction and performance. Academy of Applied Psychology, 90(5), 945–955. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.945.

Ashkanasy, N. M., & O’Connor, C. (1997). Value congruence in leader–member exchange. The Journal of Social Psychology, 137(5), 647–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224549709595486.

Baldassare, M., & Katz, C. (1996). Measures of attitude strength as predictors of willingness to speak to the media. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 73(1), 537–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909607300113.

Bardi, A., & Schwartz, S. H. (2003). Values and behavior: Strength and structure of relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(10), 1207–1220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203254602.

Bem, D. J. (1967). Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychological Review, 74(3), 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0024835.

Binder, A. R., Dalrymple, K. E., Brossard, D., & Scheufele, D. A. (2009). The soul of a polarized democracy. Testing theoretical linkages between talk and attitude extremity during the 2004 presidential election. Communication Research, 36(3), 315–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650209333023.

Bowen, D. E., Ledford, G. E., & Nathan, B. R. (1991). Hiring for the organization, not the job. Academy of Management Perspectives, 5(4), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.1991.4274747.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Socialized charismatic leadership, values congruence, and deviance in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 954–962. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.954.

Byrne, D. (1971). The attraction paradigm. New York: Academic Press.

Cha, S. E., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). When values backfire: Leadership, attribution, and disenchantment in a values-driven organization. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.10.006.

Cropanzano, R., Dasborough, M. T., & Weiss, H. M. (2017). Affective events and the development of leader–member exchange. Academy of Management Review, 42(2), 233–258. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0384.

Crowne, D. P., & Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 24(4), 349–354. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0047358.

De Dreu, C. K. (2007). Cooperative outcome interdependence, task reflexivity, and team effectiveness: A motivated information processing perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 628–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.628.

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis and consequences of leader–member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1715–1759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311415280.

Edwards, J. R. (1993). Problems with the use of profile similarity indices in the study of congruence in organizational research. Personnel Psychology, 46(3), 641–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb00889.x.

Edwards, J. R. (1994). The study of congruence in organizational behavior research: Critique and a proposed alternative. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 58(1), 51–100. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1994.1029.

Edwards, J. R. (2002). Alternatives to difference scores: Polynomial regression analysis and response surface methodology. In F. Drasgow & N. W. Schmitt (Eds.), Advances in measurement and data analysis (pp. 350–400). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Edwards, J. R. (2008). Person-environment fit in organizations: An assessment of theoretical progress. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 167–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520802211503.

Edwards, J. R., & Cable, D. M. (2009). The value of value congruence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 654–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014891.

Edwards, J. R., & Parry, M. E. (1993). On the use of polynomial regression equations as an alternative to difference scores in organizational research. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1577–1613. https://doi.org/10.2307/256822.

Ely, K., Boyce, L. A., Nelson, J. K., Zaccaro, S. J., Hernez-Broome, G., & Whyman, W. (2010). Evaluating leadership coaching: A review and integrated framework. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(4), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.06.003.

Erdogan, B., Kraimer, M. I., & Liden, R. C. (2004). Work value congruence and intrinsic career success: The compensatory role of leader–member exchange and perceived organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 57(2), 305–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.tb02493.x.

Feather, N. T. (2004). Value correlates of ambivalent attitudes toward gender relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203258825.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Finegan, J. E. (2000). The impact of person and organizational values on organizational commitment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(2), 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317900166958.

Fischer, J. G. (2014). Strategic brand engagement: Using HR and marketing to connect your band customers, channel partner and employees. London: Kogan Page.

Fritzsche, E., & Oz, E. (2007). Personal values’ influence on the ethical dimension of decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 75(4), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9256-5.

Gabriel, A. S., Diefendorff, J. M., Chandler, M. M., Moran, C. M., & Greguras, G. J. (2013). The dynamic relationships of work affect and job satisfaction with perceptions of fit. Personnel Psychology, 67(2), 389–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12042.

Graen, G. B., & Scandura, T. A. (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Research in Organizational Behavior, 9, 175–208.

Gregory, B. T., Albritton, M. D., & Osmonbekov, T. (2010). The mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relationships between P-O fit, job satisfaction, and in-role performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(4), 639–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9156-7.

Hayibor, S., Agle, B. R., Sears, G. J., Sonnenfeld, J. A., & Ward, A. (2011). Value congruence and charismatic leadership in CEO-top manager relationships: An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0808-y.

Henderson, D. J., Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., Bommer, W. H., & Tetrick, L. E. (2008). Leader–member exchange, differentiation, and psychological contract fulfillment: A multilevel examination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1208–1219. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012678.

Hewlin, P. F., Dumas, T. L., & Burnett, M. F. (2017). To thine own self be true? Facades of conformity, values incongruence, and the moderating impact of leader integrity. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1), 178–199. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0404.

Hinojosa, A. S., McCauley, K. D., Randolph-Seng, B., & Gardner, W. L. (2014). Leader and follower attachment styles: Implications for authentic leader–follower relationships. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(3), 595–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.12.002.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Joyner, B. E., & Payne, D. (2002). Evolution and implementation: A study of values, business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 41(4), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021237420663.

Jung, D. I., & Avolio, B. J. (2000). Opening the black box: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of trust and value congruence on transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(8), 949–964. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200012)21:8<949:AID-JOB64>3.0.CO;2-F.

Kemelgor, B. H. (1982). Job satisfaction as mediated by the value congruity of supervisors and their subordinates. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 3(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030030202.

Kim, T., & Kim, M. (2013). Leaders’ moral competence and employee outcomes: The effects of psychological empowerment and person–supervisor fit. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(1), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1238-1.

Kirkman, B. L., & Rosen, B. (1999). Beyond self-management: Antecedents and consequences of team empowerment. Academy of Management Journal, 42(1), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/256874.

Krishnan, V. R. (2012). Transformational leadership and personal outcomes: Empowerment as mediator. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 33(6), 550–563. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437731211253019.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Jansen, K. J., & Colbert, A. E. (2002). A policy-capturing study of the simultaneous effects of jobs, groups, and organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 985–993. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.5.985.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., & Stevens, C. K. (2001). Goal congruence in project teams: Does the fit between members’ personal mastery and performance goals matter? Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(6), 1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.6.1083.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person–organization, person-group, and person supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x.

Krosnick, J. A., & Petty, R. E. (1995). Attitude strength. Antecedents and consequences. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum Associates.

Krosnick, J. A., & Smith, W. A. (1994). Attitude strength. In V. S. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Kunin, T. (1955). The construction of a new type of attitude measure. Personnel Psychology, 8(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1955.tb01189.x.

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2000). An examination of the mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relations between the job, interpersonal relationships, and work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 407–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.407.

Lord, R. G., & Brown, D. J. (2001). Leadership, values, and subordinate self-concepts. The Leadership Quarterly, 12(2), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(01)00072-8.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83.

Maier, G. W., & Woschée, R. M. (2002). Die affektive Bindung an das Unternehmen. Die affektive Bindung an das Unternehmen. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 46(3), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1026//0932-4089.46.3.126.

Meglino, B. M., Ravlin, E. C., & Adkins, C. L. (1989). A work values approach to corporate culture: A field test of the value congruence process and its relationship to individual outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(3), 424–432. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.3.424.

Menon, S. T. (1999). Psychological empowerment: Definition, measurement, and validation. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 31(3), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087084.

Meyer, J. P., Hecht, T. D., Gill, H., & Toplonytsky, L. (2010). Person–organization (culture) fit and employee commitment under conditions of organizational change: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(3), 458–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.01.001.

Neuberger, O., & Allerbeck, M. (1978). Messung und Analyse von Arbeitszufriedenheit: Erfahrungen mit dem “Arbeitsbeschreibungsbogen (ABB)”. [Measure and analysis of job satisfaction: Experience with the “Arbeitsbeschreibungsbogen (ABB)”]. Bern: Huber Verlag.

Nishii, L. H., & Mayer, D. M. (2009). Do inclusive leaders help to reduce turnover in diverse groups? The moderating role of leader-member exchange in the diversity to turnover relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1412–1426. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017190.

Ogunfowora, B. (2014). The impact of ethical leadership within the recruitment context: The roles of organizational reputation, applicant personality, and value congruence. The Leadership Quarterly, 25(3), 528–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.11.013.

Posner, B. Z. (2010). Another look at the impact of personal and organizational value congruency. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(4), 535–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0530-1.

Qu, Y. E., et al. (2017). Should authentic leaders value power? A study of leaders’ values and perceived value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3617-0.

Ravlin, E. C., & Ritchie, C. M. (2006). Perceived and actual organizational fit: Multiple influences on attitudes. Journal of Managerial Issues, 18(2), 175–192. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40604533.

Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Schwartz, S. H., & Knafo, A. (2002). The big five personality factors and personal values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(6), 789–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202289008.

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: Free Press.

Schein, E. H. (2010). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Schmidt, P., Bamberg, S., Davidov, E., Herrmann, J., & Schwartz, S. H. (2007). Die Messung von Werten mit dem „Portraits Value Questionnaire“. [The measurement of values with the „portraits value questionnaire“]. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 38(4), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1024/0044-3514.38.4.261.

Schneider, B. (2001). Fits about fit. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50(1), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00051.

Schuh, S. C., Van Quaquebeke, N., Keck, N., Göritz, A. S., De Cremer, D., & Xin, K. R. (2015). Does it take more than ideals? How counter-ideal value congruence shape employees’ trust in the organization. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3097-7.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego: Academic.

Schwartz, S. H. (1996). Value priorities and behavior: Applying a theory of integrated value systems. In C. Seligman, J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The psychology of values: The Ontario Symposium. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Schwartz, S. H., & Bardi, A. (2001). Value hierarchies across cultures: Taking a similarities perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(3), 268–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032003002.

Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Vecchione, M., Davidov, E., Fischer, R., Beierlein, C., et al. (2012). Refining the theory of basic individual values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(4), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029393.

Seibert, S. E., Wang, G., & Courtright, S. H. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 981–1003. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022676.

Shanock, L. R., Baran, E. B., Gentry, W. A., Pattison, S. C., & Heggestad, E. D. (2010). Polynomial regression with response surface analysis: A powerful approach for examining moderation and overcoming limitations of difference scores. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(4), 543–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9183-4.

Sherif, M., & Hovland, C. I. (1980). Social judgment: Assimilation and contrast effects in communication and attitude change. Westport: Greenwood.

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. https://doi.org/10.2307/256865.

Srivastava, A., Bartol, K. M., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Empowerment leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1239–1251. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2006.23478718.

Suazo, M., Turnley, W. H., & Mai-Dalton, R. R. (2005). Antecedents of psychological contract breach: The role of similarity and leader–member exchange. Academy of Management, Best Paper Proceedings. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2005.18780720.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x.

Thomas, K. W., & Velthouse, B. A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Academy of Management Review, 15(4), 666–681. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1990.4310926.

Turban, D. B., & Jones, A. P. (1988). Supervisor-subordinate similarity: Types, effects and mechanisms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(2), 228–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.73.2.228.

Van Quaquebeke, N., Graf, M. M., Kerschreiter, R., Schuh, S. C., & Van Dick, R. (2014). Ideal values and counter-ideal values as two distinct forces: Exploring a gap in organizational value research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12017.

Van Vianen, A. E. M., Shen, C. T., & Chuang, A. (2011). Person–organization and person–supervisor fits: Employee commitments in a Chinese context. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(6), 906–926. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.726.

Voss, Z. G., Cable, D. M., & Voss, G. B. (2006). Organizational identity and firm performance: What happens when leaders disagree about “who we are?”. Organization Science, 17(6), 741–755. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0218.

Walter, F., & Bruch, H. (2008). The positive group affect spiral: A dynamic model of the emergence of positive affective similarity in work groups. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(2), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.505.

Wisse, B., & Rietzschel, E. (2014). Humor in leader-follower relationships: Humor styles, similarity and relationship quality. International Journal of Humor Research, 27(2), 183–400. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2014-0017.

Zhang, X. M., & Bartol, K. M. (2010). Linking empowering leadership & employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, & creative process engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2010.48037118.

Zhang, Z., Wang, M., & Shi, J. (2012). Leader–follower congruence in proactive personality and work outcomes: The mediating role of leader–member exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0865.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Byza, O.A.U., Dörr, S.L., Schuh, S.C. et al. When Leaders and Followers Match: The Impact of Objective Value Congruence, Value Extremity, and Empowerment on Employee Commitment and Job Satisfaction. J Bus Ethics 158, 1097–1112 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3748-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3748-3