Abstract

This paper examines the antecedents of felt trust, an under-explored area in the trust literature. We hypothesized that subordinates’ felt trust would relate positively with their leaders’ moral leadership behaviors and negatively with autocratic leadership behaviors and demographic differences between leaders and themselves. We also hypothesized the above relationships to be mediated by the leader-member value congruence. Results supported our hypotheses that value congruence mediated between autocratic leadership behaviors and demographic differences and subordinates’ felt trust, but not moral leadership behaviors, which had direct effects on subordinates’ perception of feeling trusted. Theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Trusting and feeling trusted represent the two sides of a trusting work relationship. However, current research on interpersonal trust focuses only on trusting. Typical research questions include: how much subordinates trust their leaders; the antecedents leading to such trust; and its consequences, such as organizational commitment, turnover, citizenship behaviors, and deviant behaviors (Aryee, Budhwar, & Chen, 2002; Dirks & Ferrin, 2002; Mayer & Gavin, 2005). Although the perceptions of being trusted will probably affect subsequent behaviors of trusted others and the future relationship between the two parties, little research has been done on whether trusted others feel trusted by trustors. Other than two journal articles on the reactions of trusted parties in experimental settings (Malhotra, 2004; Pillutla, Malhotra, & Murnighan, 2003), database searches using the terms “felt trust,” “trusted parties,” and “trusted other” showed no prior publication. Because of the lack of research in this area, we have very little understanding of the perceptions and reactions of the trusted parties. This paper aims at addressing this missing link in the trust literature (e.g., Lau, 2001; Mayer, Davis, & Schoorman, 1995) by examining factors that are associated with employees’ perceptions of feeling trusted by their supervisors in the work place.

There are at least three reasons why the awareness of being trusted is important. First, being trusted may result in a sense of obligation or responsibility in the trusted person to carry out duties or tasks as expected by trustors. As Deutsch (1958: 268) suggested, a “trustworthy person is aware of being trusted and that he is somewhat bound by the trust invested in him.” Second, being trusted is a form of psychological empowerment. It is an active orientation to one’s work role, which consists of four cognitive aspects: meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact (Spreitzer, 1995). With votes of confidence from supervisors in terms of ability, benevolence, and integrity, subordinates will likely feel more encouraged and be determined to continue their courses of action. Third, feeling trusted is also a source of self-efficacy (Conger & Kanungo, 1988). With such perceptions, trusted others will probably feel obligated, empowered, and confident in fulfilling the expectations of the trustors.

Trust features preeminently in interpersonal relationships. In a relationship-oriented society such as China, reliance on relationship-based trust has cultural roots (Tan & Chee, 2005). The weak institutionalized rules in current China also force people to rely on trust for coordination and information sharing (Xin & Pearce, 1996). With China rapidly becoming “a mega market” (Hui & Graen, 1997: 452) for the world economy, it is of great theoretical as well as practical significance to choose Chinese managers as a research sample to address the missing link in the trust literature.

Drawing on literature on interpersonal trust, leadership and relational demography, we propose that autocratic and moral leadership behaviors among Chinese business leaders, and demographic similarities between leaders and their subordinates are antecedents of the extent to which these followers will feel trusted. Furthermore, value congruence forms a critical foundation for trust to develop between two parties, and violating such congruence was found to have profound effects in trust development (Sitkin & Roth, 1993). Previous studies show that leadership styles (Jung & Avolio, 2000), including transformational and transactional, and demographic differences (Jehn, Chadwick, & Thatcher, 1997) were correlates of value congruence between leaders and subordinates.

In this study, we examine the mediating role of value congruence on the respective relationships between the two sets of variables and the level of leaders’ trust in them as perceived by the followers. By doing so, we hope to contribute to the understanding of the dynamics of building long-term and iterative trust relationships. By examining the reasons why employees feel trusted, we move one step closer to understanding the complete process of trusting and being trusted and disentangling these two related but distinctly different concepts. Focusing on the effects of autocratic and moral leadership behaviors on followers’ felt trust by their leaders, we also hope to contribute to the leadership literature and the Chinese management literature because these two types of leadership behaviors are very popular among Chinese leaders and known to produce very opposite results (Farh & Cheng, 2000).

Subordinates’ feeling trusted by their leaders

Trust relationships between trustors and the trusted are embedded in social relationships (Granovetter, 1985): the two parties need to go through multiple rounds of social exchanges before their trust for each other matures. When established, mutual trust, respect and obligation become characteristics of a quality relationship (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). The dyadic relationships and work roles developed or negotiated over time through a series of exchanges, or “interacts,” between leader and member also forms the theoretical basis for the leader-member exchange (LMX) theory. As the level of trust increases between the two, the leader may offer increased job latitude or delegation to the member, who, in turn, may offer stronger commitment or higher levels of effort to work goals and performance to the leader. High-quality LMX relationships are seen as evidence of successful trust-building over time (Bauer & Green, 1996).

To understand the dynamics of trusting relationships, it is important to understand the rationale for both the trusting (trustors) and those who feel trusted. To trust, trustors are willing “to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party” (Mayer et al., 1995: 712). To feel trusted, the other party has to perceive that the trustor possesses the above-described willingness to take risks with the relationship.

Trusting and feeling trusted are independent constructs, although they are often mentioned together (Brower, Schoorman, & Tan, 2000). Sometimes trustors’ trust may not be felt by trusted others because trusting and feeling trusted are attitudes and perceptions of two different parties. Sometimes trust may be misinterpreted by the trusted parties because of dispositional characteristics of trusted parties (Kramer, 1995), influence of significant others (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978; Shah, 1998), or organizational factors affecting trust attributions, e.g., binding contracts (Malhotra & Murnighan, 2002). In these scenarios, trusting and feeling trusted tend not to align. In this study, we focus on the influence of leaders on subordinates’ perception of being trusted because leaders’ influence is essential within vertical dyads.

Similarly, feeling trusted and trustworthiness are two distinct concepts. Trustworthiness is the cognitive assessment of the trusted other’s ability, benevolence, and integrity (Mayer et al., 1995). When trustors find others trustworthy, they will place trust in them (Gillespie, 2003; Mayer & Davis, 1999). Whereas, feeling trusted is the trusted other’s own perception of whether he or she is trusted by others. The concepts of trustworthiness and feeling trusted are probably related because individuals’ trustworthiness may enhance others’ trust, which may in turn increase individuals’ perception of feeling trusted, but the two trust-related constructs are conceptually different.

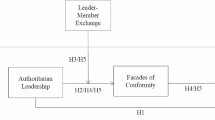

Consequently, antecedents of trust and being trusted may also be different. Drawing on prior research, we propose that leadership behaviors, demographic, and value differences are related to subordinates’ perception of whether their leaders trust them (see Figure 1).

Antecedents of felt trust—leadership behaviors

Although the effects of many different types of leadership behaviors have been examined (Yukl, 2002), we focus on moral leadership and autocratic leadership in this study because these two types of behaviors are very typical and influential among Chinese business leaders (Farh & Cheng, 2000).

Moral leadership

Moral leadership refers to leadership that is unselfish, righteous, and fair to all (Hui & Tan, 1999). Moral leaders have been highly respected throughout Chinese history, and moral leadership behaviors are regarded as essential for leadership effectiveness in modern China because the legal system and institutional norms are still evolving. In the absence of codified rules and regulations and effective enforcement mechanisms, leaders have to rely heavily on a value influence process in order to lead effectively. Such reliance was recognized when the two-dimensional behavior theory (people-oriented vs. task-oriented) was first introduced and tested in China in early 1980s. Chinese researchers found that moral leadership had to be added as the third dimension in order to account for significant variances in the effectiveness of Chinese business leaders (Ling, Chen, & Wang, 1987). Moral leadership style is also included in the model of paternalistic leadership by Farh and his colleagues (Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang, & Farh, 2004; Farh & Cheng, 2000).

An important and relevant aspect of moral leadership is about being fair or being just. Prior research on justice perceptions and trust relationships indicates that these two constructs are positively related. When subordinates experience justice in the work place, they will trust their supervisors more (Aryee et al., 2002; Konovsky & Pugh, 1994). A recent study on guanxi (the ties between two individuals) practices further supports this relationship: recruitment through guanxi brought detrimental procedural justice perceptions and negative trust relationships between management and subordinates (Chen, Chen, & Xin, 2004). Trust relationships were further damaged when the guanxi bases were personal, such as close relatives, rather than distant, such as schoolmates. Such findings implied a negative relationship between favouritism and trust relationship. Thus we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 1

Moral leadership behaviors are positively related to the extent to which subordinates feel trusted by their leaders.

Autocratic leadership

Autocratic leadership refers to leadership behaviors that assert absolute authority and control over subordinates and demand unquestioning obedience from subordinates (Himes, 1980; Lewin, Lippitt, & White, 1939). The traditional Chinese culture, characterized by “the natural acceptance of hierarchical structuring and legitimization for unequal superior–subordinate relationships, the dutiful fulfillment of role duties, and tendencies toward deference, compliance and conformity to authority” (Westwood & Leung, 1996: 390–391), has nurtured a large number of autocratic leaders.

The exposure to Western philosophies and the recent reforms in China have greatly expanded Chinese people’s visions and made them redefine their expectations of a good leader. For example, the once popular autocratic leadership is now the least preferred style of leadership and employees under such leadership reported very low level of job satisfaction as compared to those under leaders with different styles (see Fu, Chow, & Zhang, 2002a). In fact, the best outcome autocratic leadership behaviors can produce is compliance; very seldom do they lead to commitment (Liu, 2005). Both Western as well as Chinese research findings have shown that autocratic leadership behaviors positively correlate with the level of dissatisfaction in followers (Dorfman, Howell, Hibino, Lee, Tate, & Bautista, 1997; Fu et al., 2002a). Such explicit dissatisfaction may very likely be caused by the lack of felt trust.

Furthermore, being self-centered and usually indifferent to the needs and desires of the followers, autocratic leaders seldom delegate or empower their followers in the decision-making processes (e.g., Dorfman et al., 1997). Instead, they closely monitor their followers’ behaviors and expect them to follow the decisions when made, thus creating a mutually distrusting working environment. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 2

Autocratic leadership behaviors are negatively related to the extent to which subordinates feel trusted by their leaders.

Antecedents of felt trust—demographic differences

Demographic differences refer to discrepancies in attributes such as religion, national origin, gender, age and education. We will not examine differences in race or religion since the working population in China is predominantly Chinese and agnostic. Instead, we focus on differences in age and education in this study because the effects of differences in these two variables between dyads or among group members have been found to affect leader–member relationships in Chinese firms (Fu et al., 2002b). Differences in age and education are also said to often represent cognitive differences (Allinson, Armstrong, & Hayes, 2001), which may lead to potential differences in management styles and potential conflict, which, in turn, may erode the trust between leaders and subordinates.

Demographic attributes have been used as bases for self-categorization, especially before other types of relationships have been formed. For example, social identity theory suggests that individuals identify themselves with salient social groups to enhance their own self-worth (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). When supervisors and subordinates are different in some salient demographic attributes, they are unlikely to share similar social identity, which in turn makes it more difficult for them to establish close relationships with each other. At the worst extreme, negative stereotypes of demographic minorities may be formed (Flynn, Chatman, & Spataro, 2001). In addition, supervisors and subordinates may focus on individual differences rather than organizational objectives, thus the chance of working towards similar preferences and priorities in work goals is also reduced (Chatman & Flynn, 2001).

According to Tsui and O’Reilly (1989), demographic differences increase social distances between leaders and subordinates. Demographically different people tend not to attract each other, and their communication frequency is usually negatively affected (Byrne, 1971). The lack of communication increases potential role conflict and role ambiguity because subordinates may not understand their leaders’ expectations or plans (Tsui & O’Reilly, 1989). In addition, social distance increases the difficulty in communicating leaders’ intentions and preferences and, as a result, clarity of leaders’ values may be compromised. Accumulated misunderstandings will probably undermine the process of building similar values between leaders and subordinates, thus making it difficult to establish the trust between the two parties. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 3

Demographic differences between leaders and subordinates, in terms of age and educational level, are negatively related to the extent to which subordinates feel trusted by their leaders.

Mediator—value congruence

Values are internalized attitudes about what is right and wrong, ethical and unethical, important or unimportant (Rokeach, 1979). According to Fishbein and Ajzen’s (1975) value–attitude–behavior model, values help individuals formulate attitudes and beliefs and, in turn, how people behave. In most organizational settings, values relate to members’ beliefs in the significance of organizational goals and behavioral modes (Meglino & Ravlin, 1998; Posner & Schmidt, 1992). In order to motivate followers, leaders often have to link their requests to what followers believe are important (Klein & House, 1995; Sosik, 2005). By aligning two parties’ values, leaders can easily get followers’ endorsement and support for those requests.

We propose that value congruence between leaders and their followers mediates the relationship between leadership behaviors and followers’ perception of being trusted by their leaders. The extent to which the values held by the leader are shared by the followers affects the amount of trust the leader may have in the followers. When the values are similar, leaders can be confident that their followers will not deviate from their goals and intentions and therefore are likely to trust their followers to attain organizational goals and, correspondingly, followers will feel trusted (e.g., Jung & Avolio, 2000; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, & Fetter, 1990). Value congruence is also related to followers’ perceptions. When leaders and their followers disagree with each other as to what organizational outcomes are important, difficulties in communication and conflict will increase (Meglino & Ravlin, 1998), and followers will be unlikely to feel trusted by their leaders.

In this study we specifically use the perceived importance of various organizational outcomes as indicators of the values leaders and members hold because values affect our judgment, and empirically, they have also been found to affect leaders’ perceptions of situations and perceptions of individual and organizational successes (England & Lee, 1974; Posner & Schmidt, 1992). Based on existing leadership research, we can infer that moral leaders have more referent power. When leaders demonstrate moral leadership, even followers who originally held dissimilar values may be attracted to these leaders due to their admirable virtues and the fair treatment they give their subordinates (Krishnan, 2003). Therefore, moral leaders and their followers will appear to share similar values.

-

Hypothesis 4

Leader–subordinate value congruence will mediate the relationship between moral leadership behaviors and subordinates’ perception of being trusted (by their leaders), i.e., moral leadership behaviors are positively related to leader–subordinate value congruence, which in turn is positively related to the level of subordinates’ felt trust.

Having strong desires for control and for absolute power, autocratic leaders may not be willing to place a high level of trust or empower their followers (Dorfman et al., 1997). Instead, they may install more monitoring devices and processes to ensure their followers complete the assigned tasks as ordered. Their behaviors usually create an undesirable model such that subordinates will not identify and adopt their values. When that happens, subordinates are unlikely to share their opinions about the importance of different organizational outcomes, and the differences in values will make them feel less trusted by their leaders. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 5

Leader–subordinate value congruence will mediate the relationship between autocratic leadership behaviors and subordinates’ perception of being trusted (by their leaders), i.e., autocratic leadership behaviors are negatively related to leader–subordinate value congruence, which in turn is positively related to the level of subordinates’ felt trust.

Given the difficulty of initiating close relationships and the increased possibility of misunderstanding and forming bad impressions, leaders may not trust demographically different subordinates. People in different age groups and with different levels of education are found to hold different values (Egri & Ralston, 2004; Fu et al., 2002b). When followers hold different values from their leaders, leaders may monitor more closely to ensure goal alignment or assume less risk with their followers through less delegation, and therefore followers are unlikely to feel trusted. Thus, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 6

The negative relationship between leader–subordinate age and educational differences and subordinates’ perception of being trusted (by their leaders) is mediated by leader–subordinate value congruence, i.e., differences in age and education are negatively related to leader–subordinate value congruence, which in turn is positively related to the level of subordinates’ felt trust.

Materials and methods

Sample and data collection

Data were collected from 95 firms located in five cities: Beijing, Shanghai and Suzhou in southern China, Chongqing in central China, and a port city of Dalian in northeast China, reflecting diverse geographical locations and industrial characteristics. Survey data were collected between May 2000 and July 2001. For each occasion, the top leader of the company was first interviewed and the questionnaires were administrated through him or her. The questionnaire consisted of two types: one for the leader, and the other for four to six of the leader’s direct subordinates. The leader questionnaire included the leaders’ opinions of the company’s outcomes, leaders’ demographics, and information on the company’s history and performance. The subordinate questionnaire included the subordinates’ perceptions of their leaders’ behaviors, opinions of company outcomes, demographics, and the extent to which their leaders trust them.

To ensure that subordinates evaluated the designated leader, we wrote the name of the leader on the cover page of each subordinate’s questionnaire, together with a description of the research purpose. We also provided each respondent a self-stamped and self-addressed envelope to send the response directly back to us to ensure confidentiality. A total of 467 questionnaires were distributed to 97 leaders and 370 subordinates in 95 firms, of which 389 (95 from leaders and 294 from their subordinates) were returned. The average response rate was 83%.

Out of the total sample, responses from 244 leader–subordinate dyads, collected from 85 leaders and their 244 subordinates, were used for the analyses after excluding cases with missing data. The average usable response rate was 70%. The 85 firms covered various industries, with most in manufacturing (47%) and trade (25%). The majority of the firms (60%) were entrepreneurial. In terms of size, 47% of them were small (50 to 100 employees), 32% were medium-sized (101 to 500) and 21% were large (more than 500). Almost 90% of the leaders were male, and ages ranged from 23 to 70, with an average of 39. The profiles of the subordinates were quite similar to that of the leaders, with 66% of the respondents being male and an average age of 37, ranging from 19 to 62. The average education level of the subordinates (14 years) was also similar to that of the leaders (15 years). However, in most leader–subordinate dyads (72%), supervisors were older and more educated than subordinates. Most subordinates were top management team members and 46% held administrative or sales positions.

Measures

All items used in our measurement scales are presented in the Appendix.

Feeling trusted

was a four-item scale inductively developed in China. Since the construct has been relatively understudied, we could not find any existing scale. Even if available, they may not be totally applicable to the Chinese business context because the antecedents for feeling trusted tend to be different cross-culturally. Asking about 100 Chinese middle-level managers attending a managerial training course, we collected over 100 items from answers to the question: “What would be evidence that would demonstrate trust from your superiors in you?” Asking trusting behaviors, rather than direct questions such as whether their supervisors trusted them, we hoped to avoid social desirability effects and minimize the possibility of having multiple interpretations of felt trust among respondents (Cummings & Bromiley, 1996). Based on theoretical appropriateness and the frequency of being mentioned, we eventually picked the four items for this study. These items were translated from Chinese into English by professional translators for the study. Cronbach’s reliability coefficient was 0.74, indicating acceptable measurement reliability.

Value congruence

The general value of an object or idea to an individual is thought to be largely a function of its degree of importance to him or her (England, 1978), and such values held by a person will influence the value he or she places on certain outcomes (Feather, 1995; Prentice, 1987). Meglino and Ravlin (1998) suggested that researchers should consider the relevance of the values when they investigate organizational process and value-related phenomena. Since the relevance of values is hard to maintain using general personal value instruments, we examined the values indicated by individual judgments of the importance of major organizational outcomes such as firm profitability and customer satisfaction. Individual opinions of organizational outcomes have been used as measures of values in several other studies (e.g., Bass & Avolio, 1993; House, Javidan, Hanges, & Dorfman, 2002). We first measured the values of leaders and their subordinates separately by asking them to indicate on a seven-point Likert scale “the importance that should be assigned to each of the factors listed when making critical management decisions.” Those factors included employee orientation, customer satisfaction, firm profitability, long-term competitive capability, and impact on environment. To obtain the congruence level, we calculated the absolute leader–member score differences,Footnote 1 and then reversed the differences. Cronbach’s α for the transformed scale was 0.71, indicating acceptable reliability.

Moral leadership behaviors

were measured by three items adopted from the previous studies (House et al., 2002; Ling et al., 1987). Cronbach’s α for the construct was 0.80, indicating acceptable reliability.

Autocratic leadership behaviors

were measured by a four-item Likert scale, drawing from existing literature, including the GLOBE project (House et al., 2002). Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.69, indicating moderate but acceptable reliability.

Demographic difference

refers to gaps in age and in education. The measures were first formed by calculating the absolute age-in-year difference and the absolute difference between the leader and the subordinate in terms of years of formal education received. Considering that the impact of a difference of 1 year should not be the same across the full range of values, we recoded the measures (age and education differences) by natural log transformation. To ensure the transformed score to be positive, we added one to the absolute difference, and then conducted the transformation.

In the current study, we do not expect age difference would relate to education difference, therefore, we treat them as two independent variables.

Construct validity

Using LISREL 8.30 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993), we conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) to test the psychometric properties of those multi-indicator constructs, which included feeling trusted, value congruence, moral leadership, and autocratic leadership. Doing that, we simplified the structural model by reducing the number of indicators for each construct in order to curtail the problem of having too many indicators (Bentler & Chou, 1987). For each construct, we combined two items with the highest and the lowest factor loading into one aggregated score. We repeated the method till each factor had three indicators. As a common and acceptable practice in OB research, the method usually reduces the number of indicators to a range of two to four (e.g., Aryee et al., 2002; Hui, Law, & Chen, 1999; Mathieu & Farr, 1991).

This process resulted in a final set of 12 indicators. We then tested the discriminant validity of the four suggested constructs by contrasting a four-factor model against alternative models. Table 1 presents the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) results. The overall model chi-square, the comparative fit index (CFI, Bentler, 1990), the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI, Tucker & Lewis, 1973), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, Browne & Cudeck, 1993) were used to assess model fit. As shown in Table 1, the four-factor model fit the data well (\( \chi ^{2}_{{{\left( {48} \right)}}} = 91.71 \), p < 0.05; CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.057) and demonstrated a significant improvement from the null model. We compared our four-factor model with three alternative models: the “Three-factor model I” obtained via merging moral leadership and autocratic leadership into one factor; the “Three-factor model II” obtained by combining feeling trusted and value congruence to form a single factor; and the “Two-factor model” obtained via merging leadership and autocratic leadership into one factor and combining feeling trusted and value congruence into another factor. As shown in Table 1, the alternative models did not fit well. In additional, we used Akaike’s (1987) information criterion (AIC) to evaluate the relative fit of non-nested models (the smaller the better, Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993) and confirmed that the alternative models showed a worse fit than the four-factor model (see Table 1 for detailed information), thus providing evidence of construct distinctiveness of feeling trusted, value congruence, and the two leadership styles.

Results

Correlations among our select variables, as shown in Table 2 mostly supported our hypotheses. Feeling trust was significantly and positively related to value congruence (r = 0.23, p < 0.01), and moral leadership (r = 0.28, p < 0.01), and negatively to autocratic leadership (r = −0.15, p < 0.05), and differences in education level (r = −0.17, p < 0.05). In addition, value congruence was significantly and negatively related to autocratic leadership (r = −0.24, p < 0.01), age differences (r = −0.17, p < 0.05) and differences in education level (r = −0.23, p < 0.01), suggesting possible potential mediating effects.

LISREL 8.30 was also used to test our hypotheses, and we first compared two models, a baseline model and a full mediation model (nested under the baseline model), to test the mediation effect of value congruence (results are presented in Table 3). This analytical strategy has been used in recent OB publications (e.g., Aryee et al., 2002; Wang, Law, Hackett, Wang, & Chen, 2005). Model 0 was the baseline model with all direct effects between each independent variable (moral leadership, autocratic leadership, age difference, and education difference) and our dependent variable, feeling trusted, and the mediating effects of value congruence between each predictor and dependent variable. The model fit well (\( \chi ^{2}_{{{\left( {64} \right)}}} = 104.01 \), p < 0.05; CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.046). Having obtained the satisfying baseline model, we deleted all direct effect paths from each independent variable to feeling trusted to test the full mediation model (Model 1). The model still fit well (\( \chi ^{2}_{{{\left( {68} \right)}}} = 117.18 \), p < 0.05; CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.049), however, fit indices demonstrated a significantly worse fit than Model 0 (\( \Delta \chi ^{2}_{{{\left( 4 \right)}}} = 13.17 \), p < 0.05).

The results suggested a necessity of modification to the full mediation model that at least one of the four deleted direct paths should be kept. We then tested Models 2, 3, and 4a/b/c/d to investigate which sensitive path(s) should not be omitted from the baseline or full model: Model 2 omitted the path from value congruence to feeling trusted; Model 3 omitted paths from all independent variables to the mediating variable, value congruence. Both models fit worse than the baseline model, which suggested (1) the path from value congruence to feeling trusted was significant and should be kept for a good model fit; (2) paths from four independent variables to value congruence should not be deleted simultaneously.

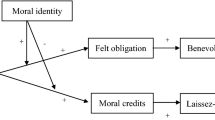

Model 4s demonstrate our more specific investigation of sensitive path(s). In each of the models, 4a/b/c/d, we took out three direct paths from the four independent variables to feeling trusted. Results of Model 4a showed the best fit (\( \chi ^{2}_{{{\left( {67} \right)}}} = 114.58 \), p < 0.05; CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.048) and no worse than the baseline model (\( \Delta \chi ^{2}_{{{\left( 3 \right)}}} = 1.73 \), p > 0.05), indicating we should keep the path from moral leadership to feeling trusted but not the other three direct paths. We also found that the path from moral leadership to value congruence was not significant and therefore redundant.

Based on the above results, we adjusted the mediation model by eliminating the path from moral leadership to value congruence, and added a direct path to felt trust, allowing moral leadership to have direct impact on feeling trusted by leaders (Model 5). The model fit well (\( \chi ^{2}_{{{\left( {68} \right)}}} = 106.28 \), p < 0.05; CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.043). Comparing Models 0, 4a, and 5, although they were not different in terms of chi-square change tests, Model 5 was the most parsimonious.

We further tested the mediating effects of value congruence by examining total, direct, and indirect effects between the predictors, mediators, and dependent variables. This approach was developed for researchers to rigorously confirm mediating hypotheses when they chose to use Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) (Bollen, 1987; Fox, 1980). This approach includes three steps. First, following the instructions of Kenny, Kashy, and Bolger (1998) for testing mediation, we decomposed the total effects of latent IVs on DVs into direct and indirect effects when running the full structural model (specified as Model 0, the baseline model). This method directly tested the indirect effects between the IV and the mediator and between the mediator and the DV, instead of comparing the difference between the total effect and the direct effect. Second, we tested the significance of the indirect effects by creating confidence intervals by bootstrapping (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). This method does not rely on the assumption that the effects are normally distributed, which is unlikely for indirect and total effects because they are formed by the products of coefficients. Third, when the indirect effects are significant (i.e., the confidence level does not include zero), mediation is confirmed regardless of whether the total effect is significant (Kenny et al., 1998).

In Table 4, we present the estimates of total, direct, and indirect effects obtained from both single sample method and bootstrap re-sampling method in which 200 bootstraps were performed. Both sets of results consistently showed significant indirect effects through the paths of autocratic leadership to value congruence to feeling trusted, and education difference to value congruence to feeling trusted, indicating that value congruence served as a mediator between autocratic leadership and feeling trusted as well as education difference and feeling trusted. H5 and part of H6 were supported. On the other hand, results indicated no mediation by value congruence between moral leadership and feeling trusted, nor between age difference and feeling trusted. Consequently, H1, but not H4, was supported. Although both effects of age difference on value congruence and value congruence on feeling trusted were significant, the comprehensive indirect effects were not statistically significant. Assessing the significant direct effects of IVs on DVs listed in Table 4, we offered Model 5 that best represented our findings and supported by the principle of parsimony. Results of path estimation (standardized values) for this modified model are indicated in Figure 2.

Discussion

The concept of trust has been used in research fields as diverse as economics, sociology, management, social psychology and occupational psychology (Clegg, Unsworth, Epitropaki, & Parker, 2002: 409). However, despite the prevalence of the construct, no research has been published on the conditions under which trusted others would feel trusted by trustors (Lau, 2001). We begin to fill this research void by developing an indigenous measure of the construct of feeling trusted and developing a model theorizing various antecedents of subordinates’ perceptions of feeling trusted by their supervisors. In addition, a complete trusting cycle involves trust initiation, a trusted party’s perception of feeling trusted, returning trust, and finally the trustor’s perception of feeling trusted by the trusted party. This assumption of a trust cycle is the basis for positive trust spirals which are widely believed to exist but not tested (Zand, 1972). Through understanding the antecedents of the trusted party’s perception of feeling trusted, we move one step closer to understanding the whole cycle.

Consistent with our predictions, we found that sharing similar values was an important antecedent of subordinates’ perception of feeling trusted by their leaders. When leaders exercised absolute control over their subordinates or when leaders and subordinates were different in education level, and then they held different values, subordinates felt that their leaders trusted them less. These findings reinforce the argument that leaders’ ability to articulate to the followers what is important is critical to generate and sustain trust and to ally with the led (Bennis, 1999).

The more leaders demonstrated moral leadership behaviors, the more subordinates would feel trusted by their leaders, but value congruence did not mediate this relationship. One possible reason could be due to the fact that when followers admire their leaders and perceive them to be moral, they would be willing to trust them regardless whether or not they share their values. Even when they find their views differ from those of the leaders, they are still likely to respect the leaders and remain committed to the leaders’ views because of their respect for and trust in the leaders. Another possible reason is that we used the importance of organizational goals but not personal or relationship values as our measure in value congruence. To confirm the mediating power of value congruence, future research needs to measure and compare the personal values of supervisors and subordinates and re-test this hypothesis.

By examining the effects of the least welcomed and most respected leadership behaviors in China, our study has also shown the direct results of such behaviors on value congruence, and thus extended the Chinese leadership literature. Both moral and autocratic leadership behaviors are components of paternalistic leadership style, a typical Chinese leadership style (Farh & Cheng, 2000). Results indicate that these two components are moderately and negatively related (r = −0.15, p < 0.05) and have opposite direct effects on value congruence, and indirectly, on subordinates’ perception of feeling trusted. The co-existence of these two seemingly contradicting leadership styles may pose an interesting research question for leadership researchers to pursue. Their impact on leader–member exchange, trust, subordinates’ morale, and other organizational outcomes are worth exploring.

Moral and autocratic leadership styles are less prevalent in western societies, probably because of different power distance, institutional and legal norms. It would be interesting to investigate whether our logic still applies in a non-Chinese context. If value congruence is a major mediator, leadership styles that enhance value congruence, including transformational leadership (e.g., Bass & Avolio, 1993), can be used as potential antecedents for perceptions of feeling trusted. Future research may test this proposition.

By understanding more about the antecedents of feeling trusted, we move one step closer to understanding the dynamics of trust building, thus adding to the trust literature. Trust researchers suggest that information importance and emotional exchange are critical components of trust (McAllister, 1995). The former element is necessary for trustworthiness evaluations, while the latter represents the basis for social or emotional bonding between trustors and trusted others. Our study suggests that different forms of similarity, in particular values and preferences, are also important bases for trust building. As trustors and trusted others realize that they have more in common, trusted others tend to feel more trusted and will likely reciprocate trust. In addition, similarities can be built through time and through multiple exchanges. Attitudinal or value similarities are potential bases for building collective identities. The theoretical and practical implications of similarity building in trust relationships are worth exploring.

Limitations

The first limitation of the study is that part of our sample was located through personal relationships among a group of Chinese researchers. Aware of the potential lack of randomness, we have included a variety of industries and organizational types in five geographically dispersed cities in the sample. Second, our data were cross-sectional in nature, and the implications on causality were limited. The directions of our hypotheses were formulated based on theories and previous research findings, but the possibility of reverse causality cannot be ruled out. For example, when leaders and subordinates differ in their values, leaders may choose to use more monitoring mechanisms and behave more autocratically to ensure task completion. Longitudinal studies could test the underlying causality. Third, the felt trust scale was newly developed in China and the statistical properties may require further testing. However, the scale had face validity, and internal reliability as measured by Cronbach’s alpha was acceptable. All of the items were selected in accordance to the trust literature and represented important work and personal risks taken by the trustors as perceived by the trusted others. Other interesting questions include whether culture affects subordinates’ feeling trusted and whether the model applies to people in firms under different systems require further studies.

Implications

Despite these limitations, our findings have significant implications for practitioners as well as academics. Recently, the world economy is in turmoil. Many organizations face the possibility of laying off employees, cutting compensation and benefits. Subordinates’ felt trust by their leaders becomes more important in maintaining their morale and work performance in the workplace. To increase felt trust, organizational leaders need to communicate their values, goals, and plans clearly to their followers and make sure that their change plans or visions are accepted if not fully internalized. Meanwhile, they should understand their moral obligations as leaders and the importance of respecting followers, thus being able to avoid being autocratic, and engage more in moral behaviors.

The same dynamics apply to foreign businesses and foreigners having to work or are going to work with Chinese employees in China. It is highly probable that Westerners will be perceived as having different cultural values than Chinese managers. To increase trust, foreign business leaders may want to understand Chinese employees’ values and try to win their trust while trying to trust them. If this is done, the negative effects of differences in values may be minimized, and Chinese subordinates may perceive that their foreign leaders trust them, and trust their leaders in return.

While ascribed demographic differences, such as age, cannot be changed, other differences such as education can be. If either leaders or subordinates have limited education, organizations may provide training on various contemporary management knowledge and styles. Educational opportunities can also be provided to help enhance communication between leaders and subordinates, thus increasing mutual trust.

Future research

Our theoretical model represents one of the first attempts to examine feeling trusted, a relatively unexplored aspect of interpersonal trust. Much remains to be studied. First, we have examined leadership behaviors and demographic differences in this study but other antecedents need to be examined. Trust does not occur in a vacuum. For example, the effects of the social network variables, such as centrality and density, and the influence of norms and expectations on felt trust, all need to be examined. Second, the effects of felt trust also need to be systematically examined. Subordinates who feel trusted may take more risks in making on-the-spot decisions or completing assigned projects. With such findings, we may know more about the individual and incremental effects of trusting and feeling trusted, and thus trusting relationships. Third, some trust researchers propose that there are multiple bases of trust (e.g., McAllister, 1995). It will be an interesting issue to investigate whether there are different bases of feeling trusted and, if so, whether they are similar to those of trusting. We speculate that it will be less clear than the trust bases because it is more difficult for the trusted others to accurately perceive the basis of trust.

In this study, we found that value congruence mediated the relationships between various leadership behaviors, demographic differences and felt trust. Other mediators, such as similar identity between leaders and subordinates, and justice perceptions, may also explain why subordinates feel more trusted. Similar identity creates common grounds for leader–member communication and trust development. Therefore, simultaneously testing the effects of other types of leadership behaviors such as consideration, maintenance, transformational or charismatic behaviors will also be an interesting topic for future research.

Results from trust studies imply that the effects of autocratic leadership behaviors are more detrimental than other types of leadership behaviors, although whether similar effects can be found between other types of behaviors on value congruence between leaders and subordinates needs to be further examined in the future. Given the importance of leaders’ moral character, the role of perceived organizational or supervisory fairness in subordinates’ trust perception cannot be ignored. Future studies may also address these potential mediators.

By examining the antecedents of feeling trusted in the Chinese context, we hope to provide Chinese business leaders as well as foreigners who are interested in working with Chinese, some insights about what makes followers feel more trusted and improve their leadership effectiveness by building a trusting relationship. We also hope, by doing so, we have initiated a new area that will stimulate future research.

Notes

To assess the degree of congruence, we consulted many kinds of direct and indirect techniques used in Personality-Organization fit literature. Among the indirect techniques, bivariate congruence indices of algebraic (X − Y), absolute (|X − Y|), or squared difference (X − Y)2 have been typically used. In the case of multiple predictors, researchers are used to combining them into a Profile similarity indices (PSIs) such as the sum of algebraic difference (D 1), the sum of absolute differences (|D|), the Euclidean distance (D), or the correlation between two profiles (Q) (Chatman, 1991; Edwards, 1993; Kristof, 1996).

References

Akaike, H. 1987. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika, 52: 317–332.

Allinson, C. W., Armstrong, S. J., & Hayes, J. 2001. The effects of cognitive style on leader–member exchange: A study of manager–subordinate dyads. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74: 201–220.

Aryee, S., Budhwar, P. S., & Chen, Z. X. 2002. Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23: 267–285.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. 1993. Transformational leadership: A response to critiques in leadership theory and research perspectives and directions. In Chemers M., & Ayman, R. (Eds.), Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions, 49–80. New York: Academic.

Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. 1996. Development of leader–member exchange: A longitudinal test. Academy of Management Journal, 39: 1538–1637.

Bennis, W. 1999. The end of leadership: Exemplary leadership is impossible without full inclusion, initiatives, and cooperation of followers. Organizational Dynamics, 28: 71–80.

Bentler, P. M. 1990. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107: 238–246.

Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. 1987. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16: 78–117.

Bollen, K. A. 1987. Total, direct, and indirect effects in structural equation models. In Clogg, C. C. (Eds.), Sociological methodology 1987, 37–69. Washingtion, DC: American Sociological Association.

Brower, H. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Tan, H. H. 2000. A model of relational leadership: The integration of trust and leader–member exchange. Leadership Quarterly, 11: 227–250.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. 1993. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen, K. A., & Long, J. S. (Eds.), Testing structural equation models, 136–162. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Byrne, D. E. 1971. The attraction paradigm. New York: Academic.

Chatman, J. A., 1991. Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36: 459–484.

Chatman, J. A., & Flynn, F. J. 2001. The influence of demographic heterogeneity on the emergence and consequences of cooperative norms in work teams. Academy of Management Journal, 44: 956–974.

Chen, C. C., Chen, Y. R., & Xin, K. 2004. Guanxi practices and trust in management: A procedural justice perspective. Organization Science, 15: 200–209.

Cheng, B. S., Chou, L. F., Wu, T. Y., Huang, M. P., & Farh, J. L. 2004. Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 7: 89–117.

Clegg, C., Unsworth, K., Epitropaki, O., & Parker, G. 2002. Implicating trust in the innovation process. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75: 409–422.

Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. 1988. The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 13: 471–482.

Cummings, L. L., & Bromiley, P. 1996. The organizational trust inventory (OTI): Development and validation. In Kramer, R. M., & Tyler, T. R. (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research, 302–319. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dansereau, F., Graen, G., & Haga, W. J. 1975. A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership within formal organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 13: 46–78.

Deutsch, M. 1958. Trust and suspicion. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2: 265–279.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. 2002. Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practices. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87: 611–628.

Dorfman, P. W., Howell, J. P., Hibino, S., Lee, J. K., Tate, U., & Bautista, A. 1997. Leadership in western and Asian countries: Commonalities and differences in effective leadership processes across cultures. Leadership Quarterly, 8: 233–274.

Edwards, J. R. 1993. Problems with the use of profile similarity indices in the study of congruence in organizational research. Personnel Psychology, 46: 641–665.

Egri, C. P., & Ralston, D. A. 2004. Generation cohorts and personal values: A comparison of China and the U.S. Organization Science, 15: 210–220.

England, G. W. 1978. Managers and their value systems: A five-country comparative study. Columbia Journal of World Business, 13: 35–44.

England, G. W., & Lee, R. 1974. The relationship between managerial values and managerial success in the United States, Japan, India, and Australia. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59: 411–419.

Farh, J. L., & Cheng, B. S. 2000. A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In Li, J. T., Tsui, A. S., & Weldon, E. (Eds.), Management and organizations in Chinese context, 84–130. New York: St. Martin’s.

Feather, N. T. 1995. Values, valences, and choice: The influence of values on the perceived attractiveness and choice of alternatives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68: 1135–1151.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. 1975. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Flynn, F. J., Chatman, J. A., & Spataro, S. E. 2001. Getting to know you: The influence of personality on impressions and performance of demographically different people in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46: 414–442.

Fox, J. 1980. Effects analysis in structural equation models. Sociological Methods and Research, 9: 3–28.

Fu, P. P., Chow, I. H. S., & Zhang, Y. L. 2002a. Leadership approaches and perceived leadership effectiveness in Chinese township and village enterprises. Journal of Asian Business, 17: 1–15.

Fu, P. P., House, R., et al. 2002b. Study of Chinese business executives: A value-based approach. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Conference, Denver, Colorado.

Gillespie, N. 2003. Measuring trust in working relationships: The behavioral trust inventory. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Conference, Seattle, Washington.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. 1995. Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader–member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6: 219–247.

Granovetter, M. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91: 481–510.

Himes, G. K. 1980. Management leadership style. Supervision, 42: 9–12.

House, R., Javidan, M., Hanges, P., & Dorfman, P. 2002. Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: An introduction to Project GLOBE. Journal of World Business, 37: 3–10.

Hui, C., & Graen, G. 1997. Guanxi and professional leadership in contemporary Sino-American joint ventures in mainland China. Leadership Quarterly, 8: 451–465.

Hui, C., Law, K. S., & Chen, Z. X. 1999. A structural equation model of the effects of negative affectivity, leader–member exchange, and perceived job mobility on in-role and extra-role performance: A Chinese case. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 77: 3–21.

Hui, C. H., & Tan, G. C. 1999. The moral component of effective leadership: The Chinese case. Advances on Global Leadership, 1: 249–266.

Jehn, K. A., Chadwick, C., & Thatcher, S. M. B. 1997. To agree or not to agree: The effects of value congruence, individual demographic dissimilarity, and conflict on workgroup outcomes. International Journal of Conflict Management, 8: 287–305.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. 1993. LISREL 8 user’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software.

Jung, D. I., & Avolio, B. J. 2000. Opening the black box: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of trust and value congruence on transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21: 949–964.

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Bolger, N. 1998. Data analysis in social psychology. In Gilbert, D., Fiske, S. T., & Lindzey, G. (Eds.), Handbook of socialpsychology (4th ed.), 233–265. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Klein, K. J., & House, R. J. 1995. On fire: Charismatic leadership and levels of analysis. Leadership Quarterly, 6: 183–198.

Konovsky, M. A., & Pugh, S. D. 1994. Citizenship behavior and social-exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 37: 656–669.

Kramer, R. M. 1995. Power, paranoia and distrust in organizations: The distorted view from the top. Research in Negotiations in Organizations, 5: 119–154.

Krishnan, V. R. 2003. Power and moral leadership: Role of self–other agreement. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 24: 345–351.

Kristof, A. L. 1996. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Personal Psychology 49: 1–49.

Lau, D. C. 2001. Job consequences of trustworthy employees: A social network analysis. Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Lewin, L., Lippitt, R., & White, R. K. 1939. Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates. Journal of Social Psychology, 10: 271–301.

Ling, W. Q., Chen, L., & Wang, D. 1987. Construction of CPM scale for leadership behavior assessment. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 2: 199–207.

Liu, J. 2005. On the relationship between CEO value transmission strategies and follower attitudes: Do leader identity and follower power orientations matter? Doctoral dissertation, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. 2004. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39: 99–128.

Malhotra, D. 2004. Trust and reciprocity decisions: The differing perspectives of trustors and trusted parties. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 94: 61–73.

Malhotra, D., & Murnighan, J. K. 2002. The effects of contracts on interpersonal trust. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47: 534–559.

Mathieu, J. E., & Farr, J. L. 1991. Further evidence for the discriminant validity of measures of organizational commitment, job involvement, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76: 127–133.

Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. 1999. The effect of the performance appraisal system on trust for management: A field quasi-experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84: 123–136.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. 1995. An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20: 709–734.

Mayer, R. C., & Gavin, M. B. 2005. Trust in management and performance: Who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss? Academy of Management Journal, 48: 874–888.

McAllister, D. J. 1995. Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38: 24–59.

Meglino, B. M., & Ravlin, E. C. 1998. Individual values in organizations: Concepts, controversies, and research. Journal of Management, 24: 351–389.

Pillutla, M. M., Malhotra, D., & Murnighan, J. K. 2003. Attributions of trust and the calculus of reciprocity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39: 448–455.

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S., Moorman, R., & Fetter, R. 1990. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Leadership Quarterly, 1: 107–142.

Posner, B. Z., & Schmidt, W. H. 1992. Values and the American manager: An update updated. California Management Review, 34: 80–94.

Prentice, D. A. 1987. Psychological correspondence of possessions, attitudes, and values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53: 993–1003.

Rokeach, M. 1979. Understanding human values. New York: Free.

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. 1978. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23: 224–253.

Shah, P. P. 1998. Who are our social referents? A network perspective to determine the referent other. Academy of Management Journal, 41: 249–268.

Sitkin, S. B., & Roth, N. L. 1993. Explaining the limited effectiveness of legalistic “remedies” for trust/distrust. Organization Science, 4: 367–392.

Sosik, J. J. 2005. The role of personal values in the charismatic leadership of corporate managers: A model and preliminary field study. Leadership Quarterly, 16: 221–244.

Spreitzer, G. M. 1995. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38: 1442–1465.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In Worchel, S., & Austin, W. (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations, 7–24. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Tan, H. H., & Chee, D. 2005. Understanding interpersonal trust in a confucian-influenced society: An exploratory study. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 5: 197–212.

Tsui, A. S., & O’Reilly, C. A. 1989. Beyond simple demographic effects: The importance of relational demography in superior–subordinate dyads. Academy of Management Journal, 32: 402–423.

Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. 1973. The reliability coeffieient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38: 1–10.

Wang, H., Law, K. S., Hackett, R. D., Wang, D., & Chen, Z. X. 2005. Leader–member exchange as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and followers’ performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 48: 420–433.

Westwood, R. I., & Leung, S. M. 1996. Work under the reforms: The experience and meaning of work in a time of transition. In Westwood, R. I. (Eds.), China review, 363–423. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

Xin, K. R., & Pearce, J. L. 1996. Guanxi: Connections as substitutes for formal institutional support. Academy of Management Journal, 39: 1641–1658.

Yukl, G. 2002. Leadership in organizations (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Zand, D. E. 1972. Trust and managerial problem solving. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17: 229–239.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Measurement scales used in this study:

Feeling Trusted

-

1.

Delegates important work to me

-

2.

Empowering me with great decision-making power

-

3.

Consults with me confidential information within my organization

-

4.

Informs me his/her personal developmental plans

Values used in measuring Value Congruence

-

1.

Employee orientation

-

2.

Customer satisfaction

-

3.

Impact on environment

-

4.

Long-term competitive capability

-

5.

Firm profitability

Moral Leadership Behaviors

-

1.

Administers rewards in a fair manner

-

2.

Uses a common standard to evaluate all who report to him/her

-

3.

Ensures that his/her behaviors are moral

Autocratic Leadership Behaviors

-

1.

Makes decisions in dictatorial way

-

2.

Is a loner, tends to work and act separately from others

-

3.

Tells subordinates what to do in a commanding way

-

4.

Is inclined to dominate others

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lau, D.C., Liu, J. & Fu, P.P. Feeling trusted by business leaders in China: Antecedents and the mediating role of value congruence. Asia Pacific J Manage 24, 321–340 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-006-9026-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-006-9026-z