Abstract

The purpose of this study is to explore whether different aspects of corporate social responsibility (i.e., economic, legal, and ethical) have independent association with job applicants’ attraction to organizations and how applicants combine the information. Further, from a person–organization fit perspective, we examine whether applicants are attracted to organizations whose corporate social responsibility (CSR) reflects their differences in ethical predispositions (i.e., utilitarianism and formalism) and Machiavellianism. Using factorial design, we created scenarios manipulating CSR and pay level. Participants read each scenario and answered questions about their attraction to the organization depicted in the scenario. We found that each aspect of CSR had an independent relationship with organizational attraction and the probability of accepting a job offer. Participants combined information from each type of CSR in an interactive, configural manner. Applicants with different ethical predispositions and Machiavellianism personality were affected by CSR to different extents. Understanding how job applicants evaluate CSR information may give managers an opportunity to influence applicant attraction. Further, our study shows that organizations may be able to maximize the utility of their CSR investments by selectively conveying CSR information in recruitment brochures that are attractive to their ideal applicants. This is the first study to examine how job applicants form their perception based upon different configurations of the multiple aspects of CSR. In addition, this is the first study to examine the moderating effect of individual differences in ethical predispositions and Machiavellianism on the relationship between CSR and applicant attraction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A slowdown in labor supply growth, coupled with increasing demand, especially in professional and service occupations, is projected to cause a labor shortage in the next decade, making the war for talent even fiercer (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor 2009). As a result, both recruitment practitioners and researchers are increasingly aware of the importance of organizational attractiveness to potential applicants (Barber 1998; Ehrhart and Ziegert 2005). Scholarly recruitment research has identified a number of antecedents of applicant attraction (see Chapman et al. 2005). One increasingly important factor is corporate social responsibility (CSR). Socially responsible firms view CSR as a source of competitive advantage by attracting a higher quality and quantity of job applicants (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Turban and Greening 1996).

Understanding more about the relationship between CSR and applicant attraction is particularly important now, given numerous corporate scandals, heighted public interest in business ethics, and the proliferation of the standards related to social performance. These changes also have an impact on the workplace, with great implications for employees. Thus, job applicants may consider a prospective employer’ social performance in addition to other aspects about organization and job (e.g., pay, type of work) in their decision-making process.

The underlying theoretical rationale for linking CSR and applicant attraction is that firms adopting socially responsible actions may develop more positive images, which yield a competitive advantage by attracting a higher quantity and quality of human resources (Davis 1973; Fombrun and Shanley 1990). To date, only a few empirical studies (e.g., Bauer and Aiman-Smith 1996; Turban and Greening 1996) have investigated the relationship between a firm’s CSR practices and applicant attraction. These studies have typically examined a set of observable corporate social activities and policies designed to address social issues such as those related to community relations, employee relations, and treatment of the environment. The multi-faceted approach of previous studies has added to our knowledge of CSR and applicant attraction. There is, however, the need for additional work that covers CSR activities encompassing economic, legal, and ethical responsibilities (Carroll 1979; Wartick and Cochran 1985; Wood 1991) and examines the relationship among them in the applicant attraction context. In the current study, we expect that each aspect of CSR would have independent relationship with applicant attraction. We also expect interaction effects wherein synergy develops among various aspects of CSR.

On an important and related note, research has shown that ethical values are a significant attribute of both organizations and individuals (Victor and Cullen 1988). Thus, it is logical to assume that individuals who place a higher value on more ethical behaviors should be attracted to more socially responsible companies that espouse higher ethical standards than to companies that do not. To date, only one study (Greening and Turban 2000) has examined this relationship in the context of person–organization (P-O) fit. Therefore, the current study extends previous research by examining the influence of CSR on applicant attraction from a P-O fit perspective. Specifically, we examine the influence of fit between individual ethical frameworks and organizational ethical values, as embodied in CSR, during job-choice process.

The purpose of this study, therefore, is twofold. First, we explore whether different aspects of CSR (i.e., economic and non-economic) have independent association with job applicants’ attraction to organizations and how job applicants combine information on multiple aspects of CSR. To do so, we employ the definition of CSR first developed by Carroll (1979) and later refined by Schwartz and Carroll (2003). They describe CSR as encompassing the entire range of obligations business has to society and involving economic, legal, and ethical responsibilities.

The second goal of this study is to examine the influence of CSR on applicants’ attraction to organizations from a P-O fit perspective. Specifically, following from an interactionist framework, we examine whether job applicants are attracted to organizations whose CSR reflects their own ethical predispositions. We do so by examining whether individual differences in ethical frameworks and Machiavellianism, a personality trait closely related to ethical decision making, moderate the influence of CSR on applicant attraction.

Review of the Literature and Hypotheses

Researchers have operationalized and studied several outcome variables associated with applicant attraction to organizations. These variables include perceptions of organizational attractiveness (e.g., Lievens and Highhouse 2003; Turban and Greening 1996; Turban and Keon 1993), job pursuit intentions (e.g., Cable and Judge 1994; Gatewood et al. 1993), acceptance intentions (e.g., Cable and Judge 1996), and actual job choice (Judge and Cable 1997). In this study, we focus on two outcomes: perceptions of organizational attraction and probability of accepting an offer if one were to be extended. These two variables have been recognized as the most important and consistent criteria to assess the utility of recruitment from the perspective of job applicants (Aiman-Smith et al. 2001; Chapman et al. 2005).

Corporate Social Responsibility

Carroll (1979) originally identified four domains of corporate social responsibility: economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary. His conceptualization provides a valuable framework for overall analyses of CSR and has been quite influential in the understanding and research of the construct. More recent work has built on Carroll’s model, reviewing and redefining the basic concept (e.g., Swanson 1995; Wood 1991). Schwartz and Carroll (2003) revisited Carroll’s (1979) seminal work and reduced the four domains down to three, making a significant case that discretionary responsibilities are best subsumed under the economic and/or ethical domains, as determined by different motivations for philanthropic activities. Following from this work, we conceptualize CSR in this study as encompassing three domains, economic, ethical, and legal.

CSR as a Predictor of Applicant Attraction

Prior empirical research of CSR and applicant attraction has begun to validate the positive link between CSR and applicant attraction (Bauer and Aiman-Smith 1996; Behrend et al. 2009; Turban and Greening 1996; Williams and Bauer 1994). The majority of these studies have emphasized specific social programs and policies directed toward different ethical issues. CSR literature has suggested that CSR is a multi-aspect construct, accommodating both economic concerns and non-economic concerns such as legal and ethical actions (Aupperle et al. 1985). Consequently, it is important to examine multiple components of CSR and investigate the extent to which they are related to applicant attraction. Building on previous research, the present study examines the relationship between the three CSR domains (i.e., economic, legal, and ethical) and applicant attraction. We expect that, as distinct components of CSR, these three domains will exert independent influence on applicant attraction. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

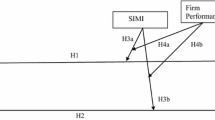

Hypothesis 1a

Higher levels of corporate economic performance will be associated with increased applicant attraction to organizations.

Hypothesis 1b

Higher levels of corporate legal performance will be associated with increased applicant attraction to organizations.

Hypothesis 1c

Higher levels of corporate ethical performance will be associated with increased applicant attraction to organizations.

Configurality of CSR

The previous hypothesis is predicated on the assumption that individuals combine information on various components of CSR in a simple additive manner. That is, the component cues are added together to arrive at an overall evaluation. Such additive models generally provide sufficiently good fit and approximate the cognitive processes underlying decision making (Goldberg 1971). Nevertheless, even though an additive model may provide an excellent approximation of data, it does not necessarily represent how the cognitive process works. As noted by Hoffman, the fitting of any mathematical model to cognitive process is at best a “paramorphic” process (1960, p. 125). That is, being able to accurately describe the judgmental process does not mean capturing the actual judgmental process. Therefore, it is worthwhile for researchers to specify other methods used by decision makers.

Configural cue processing has long been used to describe complex decision making involving multiple cues in many areas of decision making (e.g., Hitt and Barr 1989; Kristof-Brown et al. 2002). Researchers in configural cue processing have investigated the extent to which people could make decisions from a configural or multiplicative function of multiple cues (Mellers 1980). Though configural cue processing is more complex than an additive model mathematically, the former is not necessarily more difficult to process cognitively than the latter, particularly with a limited number of cues. As noted by Einhorn (1971), a model’s mathematical simplicity does not imply that it is easy to use cognitively. A mathematically more complex model may in fact be easier to use cognitively. Therefore, people may process all information and look at trade-offs between different cue values when faced with decisions involving a limited number of cues (Keeney and Raiffa 1976).

Indeed, tradeoffs and choices are inherent in ethical decision making. From a corporate perspective, profit maximization is often in conflict with pursuit of social goals such as environmental protection and product safety (Swanson 1995). As a consequence, management needs to confront the challenge of balancing the competing demands and making trade-offs between economic goals and moral duties. Prior research in socially responsible investing and consumer behavior has also indicated that investors and consumers often make ethical trade-offs between financial and ethical considerations (e.g., De Pelsmacker et al. 2005; Glac 2009). For example, De Pelsmacker et al. (2005) found that consumers make trade-offs between different attributes of a fair-trade product, a product that is bought at fair prices from farmers in developing countries for sustainable development and marketed at an ethical premium. Thus, consistent with prior work, we expect that job applicants may face the same ethical dilemma as investors and consumers. That is, they may need to make trade-offs between a high salary in one job against organizational prestige of another job.

In light of the above discussion, the present study examines whether job applicants engage in configural cue processing when they combine CSR information, that is, whether multiple CSR components interact with one another in influencing job applicants’ attraction to organizations. Specifically, we argue that the relationship between economic responsibility and applicant attraction will be strongest when the levels of both legal and ethical responsibility are high. Like job applicants choose a reservation wage and only apply to those jobs meeting their reservation wage, they might set minimum standards on each of the CSR attributes. As long as the organization meets its legal and ethical responsibility to at least a moderate degree, economic responsibility is a crucial factor influencing applicant attraction. Under such circumstances, job applicants may consider trade-offs between, for example, legal and ethical responsibility, and compensate a lack of an attribute by having a surplus of another. We expect an intensification effect wherein synergy develops among various CSR attributes. However, once the levels of legal and ethical responsibility drop below a certain level, then the appeal of high economic responsibility is diminished. Thus, we expect that the relationship between economic responsibility and attraction would be weaker when legal responsibility is low, and this buffering effect of low legal responsibility would be more pronounced when ethical responsibility is low. That is, the positive association between economic responsibility and applicant attraction is weakest when the levels of both legal and ethical responsibility are low.

Hypothesis 2

The relationship between economic responsibility and applicant attraction will be strongest when the levels of both legal and ethical responsibility are high and weakest when the levels of both legal and ethical responsibility are low.

CSR from the Perspective of Person–Organization Fit

According to Schneider’s attraction–selection–attrition model (1987), people are attracted to organizations as a function of their compatibility with the recruiting organizations. Job applicants would self-select in if there is an adequate level of P-O fit. Of particular relevance to the present study is the role of P-O fit in determining individuals’ attraction to organizations. That is, people’s preferences for particular organizations are a function of their congruence between the organizations and themselves in terms of some attributes.

While there is a plethora of evidence concerning P-O fit on applicant attraction to organizations in terms of different characteristics (e.g., Chatman 1991; Judge and Cable 1997), little research has addressed an important aspect of both organizations and individuals—ethical values. This is an important omission from the literature because on the organization side, organizational characteristics such as CSR are visible and salient for job applicants, and might be perceived as signals of organizational values and ethical climates. On the person side, individual difference in ethical frameworks and Machiavellianism may serve as relevant moderators for the relationship between CSR and applicant attraction. Accordingly, the present study examines the essentially unaddressed question concerning P-O fit: Are job applicants attracted to organizations whose CSR practices reflect their own ethical frameworks?

Earlier researchers have proposed an interactionist model of ethical decision making. For example, Victor and Cullen (1988) developed an ethical climate model to distinguish different types of ethical climates in terms of five dimensions: law and code, caring, instrumentalism, independence, and rules. They found that there existed a similarity in satisfaction levels across companies, suggesting that most employees developed “at least a palliative level of satisfaction” with their organizations’ ethical climates (p. 119). Otherwise, those who failed to fit in their organizational ethical climates would have either quit their jobs or operated in their zone of indifference. Accordingly, these authors called for more research to consider the impact of fit between individuals’ level of moral development and organizations’ ethical climate.

A number of empirical studies have provided support for the proposition that individual characteristics moderate the influence of organizational ethical environment on applicant attraction (Bauer and Aiman-Smith 1996; Behrend et al. 2009; Greening and Turban 2000; Sims and Keon 1997; Smith et al. 2004). Building on previous work, we examine whether individual differences in ethical predispositions and Machiavellianism moderate the relationship between multiple aspects of CSR and applicant attraction.

One approach to classify individual ethical decision making is by examining individuals’ ethical predispositions. Ethical predispositions refer to the cognitive frameworks individuals prefer to use in moral decision making (Brady 1985). To date, ethical predisposition researchers have focused primarily on two frameworks—utilitarianism and formalism. Utilitarians evaluate the outcomes or consequences of actions as ethical or not, rather than the actions themselves. To the extent that actions create good or minimize harm, they are ethical. Formalists, however, subscribe to a set of rules or principles for guiding behavior. To the extent that actions conform to these rules or principles, they are ethical (Brady 1985).

Individual ethical predispositions might affect applicant attraction to different organizations. Because strong utilitarians assess ethical situations in terms of consequences, they would be more likely to pay attention to the economic performance of the recruiting organizations, which has a more direct bearing on their own interest. After all, part of the basic motivation for people to enter the labor market and accept jobs is to obtain rewards from a job (Simon 1951). Thus, strong utilitarians would be more attracted to productive and profitable companies than weak utilitarians. Indeed, some P-O fit research has demonstrated that achievement-oriented applicants were more attracted to organizations with outcome-oriented cultures (Judge and Cable 1997; O’Reilly et al. 1991).

In contrast, since strong formalists emphasize the importance of rules, principles, or some other formal features of ethics to determine moral behaviors, they would be more likely to be attracted to an organization upholding its legal and ethical responsibility than weak formalists. That is, strong formalists would prefer organizations that obey the laws and society’s ethical rules, because such organizations would be seen as consistent with their process-based approach to ethical decision making.

Hypothesis 3a

The relationship between economic aspect of CSR and organizational attraction is stronger for strong utilitarians than for weak utilitarians.

Hypothesis 3b

The relationship between legal aspect of CSR and organizational attraction is stronger for strong formalists than for weak formalists.

Hypothesis 3c

The relationship between ethical aspect of CSR and organizational attraction is stronger for strong formalists than for weak formalists.

Another individual personality trait that is closely related to ethical decision making is Machiavellianism. Machiavellianism is the dispositional tendency of an individual to employ manipulative, exploitive, and devious tactics and strategies in order to achieve one’s goals without regard for feelings, rights, and needs of other people (Wilson et al. 1996). Thus, high Machs (people with high Machiavellianism) are thought to “manipulate more, win more, are persuaded less, persuade others more” than low Machs (Christie and Geis 1970, p. 312). Empirical research has demonstrated that Machiavellianism influences ethical decision-making process. High Machs tend to be less ethical in their decision making (Hegarty and Sims 1978; Singhapakdi and Vitell 1990) and view questionable business practice as more acceptable (Bass et al. 1999; Winter et al. 2004).

Because high Machs are concerned about extrinsic goal of financial success (Tang and Chen 2008), it stands to reason that high Machs applicants would be more attracted to highly profitable companies. The reasoning here is similar to that used in forming the previous hypothesis related to utilitarianism. Nevertheless, we expect high Machs would be less attracted to companies that embrace high legal and ethical standards. According to Christie and Geis (1970), certain situational factors, such as latitude for improvisation, may facilitate or mask individual characteristics of high and low Machs. In their experiments, they found that high Machs were superior in loosely structured situations where they were able to take advantage of ambiguity of the situation. In the context of our study, we argue that companies with tightly structured legal and ethical climate will be less likely to provide a favorable situation to high Machs for personal gains. In other words, such environment provides less latitude to high Machs for improvisation or exploitation. As a result, we expect that high Machs applicants would prefer companies high in the economic aspect of CSR and avoid companies high in the legal and ethical aspects of CSR.

Hypothesis 4a

The relationship between economic aspect of CSR and organizational attraction is stronger for high Machs than for low Machs.

Hypothesis 4b

The relationship between legal aspect of CSR and organizational attraction is stronger for low Machs than for high Machs.

Hypothesis 4c

The relationship between ethical aspect of CSR and organizational attraction is stronger for low Machs than for high Machs.

Study 1—Methods

Study 1 was designed to test the main and interactive relationship between economic, legal, and ethical performance and job applicants’ decision making, as well as the moderating effects of individual ethical predispositions, that is, utilitarianism and formalism.

Subjects and Procedure

Participants included 201 undergraduate business students approaching graduation at a northeastern university. The mean age of respondents was 22.7 (SD = 4.34). Across the sample, the race-ethnicity breakdown was 86.3% Caucasian, 6.1% African-American, 1.5% Hispanic, 4.1% Asian-American, and 2% other. Men comprised 61% of the sample, and the mean work experience was 6.48 years (SD = 4.72). All data used in this study were collected from written surveys distributed and collected in respondents’ classrooms by the first author at the university during a regularly scheduled class period.

The participants were instructed that the study was being conducted to explore what influences their attraction to potential employers. Each participant received a packet containing instructions, individual information survey, and scenario cards. Respondents were asked to imagine themselves as job seekers preparing to interview with an organization possessing the characteristics depicted in the scenarios. Respondents were also told to assume that all the companies and jobs were exactly the same except as described in the scenarios. At the end of each scenario, they were asked to answer a series of questions about their attraction to the organization as an employer. The respondents were advised to take a break if they felt fatigued.

Scenario Descriptions

In study 1, three CSR cue variables were manipulated: economic, legal, and ethical responsibilities. The descriptions of the low, medium, and high levels of each cue variable were derived from Clarkson (1995), Wood (1991), and Sethi (1979). Three subject matter experts reviewed the descriptions and agreed that they were adequate in portraying different levels of each CSR cue variable. Each of the manipulations is listed in Table 1. A pilot study was conducted among 10 business students to determine whether the manipulated cue levels generated the desired perceptions of low, medium, and high levels of each aspect of CSR. T tests of the mean level of perceived economic, legal, and ethical performance were performed. We found that the mean levels were significantly different among the low, medium, and high level of each cue, suggesting that respondents were able to distinguish among different levels of each aspect of CSR. Following is a sample scenario:

The company is financially stable and able to meet the needs of customers. It does not violate any applicable laws and regulations established by governments. The company complies with the basic ethical norms of the communities in which it operates but only addresses ethical lapses when its activities are made public.

An orthogonal design was deemed appropriate because firms strong in one aspect of social responsibility do not necessarily excel in the other aspects. Accordingly, all values of each CSR cue variable were fully crossed with the values of each of the others, creating every possible combination and permitting assessment of the relative importance placed on each of them by respondents (Hoffman et al. 1968). The completely crossed design resulted in 27 scenarios. Because higher-order interactions of the cues were predicted, a full factorial design was used, in which subjects were asked to judge all scenarios (Graham and Cable 2001).

Three random scenarios were replicated to assess subjects’ reliability between the scenarios, bringing the total number of scenarios to 30. We calculated test–retest correlation coefficient to determine the consistency of the responses to each of the three scenarios and their duplicates. The average correlation coefficient was .66 for attraction to organization and .67 for probability of accepting offer, indicating acceptable test–retest reliability (Benson and Clark 1982).

To minimize sequencing effects, the 30 scenarios were placed in random order before being placed in each participant’s packet. In addition, cue order within the scenarios was varied across subjects such that one-third of the sample read scenarios containing cues presented in the order (a) economic-legal-ethical, (b) ethical-economic-legal, or (c) legal-ethical-economic. This strategy allowed us to test for cue order effects while maintaining consistency in cue presentation within subjects to minimize confusion (Kristof-Brown et al. 2002). One-way ANOVAs of cue order indicated no significant differences in the dependent variables.

Individual Difference Variables

Utilitarianism and formalism were measured with the character traits version of Brady and Wheeler’s (1996) measure of ethical predispositions. Respondents rated 13 character traits on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (not important to me) to 7 (very important to me). Utilitarianism included traits of innovative, resourceful, effective, influential, results oriented, productive, and a winner. Formalism included the traits of principled, dependable, trustworthy, honest, noted for integrity, and law abiding. These two scales had Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities of .74 and .70, respectively.

Dependent Variables

Perception of organizational attraction was measured with three items using a 7-point scale (1 = not at all, 7 = to a very great extent), adapted from Turban et al. (2001). Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they would like to work for this company, would choose this company as one of their first choices as an employer, and would find a job with this company attractive. The Cronbach’s alpha was .98. Participants were also asked to indicate the likelihood that they would accept an offer of employment at this company, if one were made.

Analyses

Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002) has been advocated for use with a policy-capturing design, because it allows an examination of within- and between-subjects variance (Morrison and Vancouver 2000; Rotundo and Sackett 2002). Specifically, each subject’s decision policy is captured at the within-subjects level of analysis. At the between-subjects level of analysis, the focus is on the impact of decision makers’ characteristics on their decision policies (Klaas et al. 2006).

According to Hofmann and Gavin (1998), grand mean centering level-1 predictors is superior to a raw metric approach in hierarchical linear models, because the former can reduce multicollinearity problems in level-2 analysis. However, centering would not make the intercept term more interpretable in the present study because the cue levels were experimentally controlled and the same across subjects (Kristof-Brown et al. 2002). Therefore, the level-1 predictors were used in their original metric without centering. The level-2 predictors were grand mean centered before entering in the HLM analyses.

Study 1—Results

Hypothesis testing in HLM involves evaluating a series of models. We first ran a null, unconstrained model with no level-1 or level-2 predictors. The results provided evidence of significant between-subjects variance in perception of organizational attraction (τ00 = 0.28, df = 200, χ2 = 671.72, p < .001) and probability of accepting offer (τ00 = 139.85, df = 200, χ2 = 1066.61, p < .001), thereby justifying further cross-level analyses. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were 7.3% and 12.6%, indicating that about 7% of the variance in perception of organizational attraction and 13% of the variance in probability of accepting offer were between individuals (Table 2). Though the ICCs were not high, they suggested that a multilevel model incorporating within- and between-subjects factors may be useful (Luke 2004).

Within-Subjects Analyses

In order to test the direct relationship between CSR cues and the two outcome variables, we ran a random coefficient model with the three CSR cues as level-1 predictors and the two outcome variables as level-1 dependent variables. The regression coefficients were modeled as random effects at level 2, varying as a function of a grand mean and a random error. There were no level-2 predictors in this model. As can be seen in Table 3, the average slope coefficient for each of the three cue variables was positive and statistically significant. The positive direction on each of the coefficients indicated that as levels of the cue variables rose, on average, perception of organizational attraction and probability of accepting offer increased, supporting Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c. The largest average coefficient was for legal responsibility (γ20 = 1.08 & 16.99), followed by economic (γ10 = .98 & 15.90) and ethical responsibility (γ30 = .93 & 14.79). The random-effects variance components in the random coefficient model were all greater than zero, suggesting unmodeled variability. Thus, adding more predictors to the model was warranted.

Within-Subjects Interaction Effects

Hypothesis 2 proposed that information on economic, legal, and ethical responsibility cues would interact multiplicatively to influence job applicants’ attraction to organizations. Therefore, we used SAS Proc Mixed to test the incremental variance explained by the two- and three-way interactions among responsibility cues. The advantage of SAS Proc Mixed over HLM is that it can model the interaction effects among predictors at the same level while modeling the random effects.

The results are presented in Table 4. Because lower-order interactions cannot be interpreted in the presence of significant higher-order interactions (Aiken and West 1991), only the highest-order significant interactions were of interest in the present study. The three-way interaction was statistically significant for probability of accepting offer (β = .97, p < .05), partially supporting Hypothesis 2. Although not hypothesized, we found two-way interaction effects between economic and legal responsibility for organizational attraction (β = .16, p < .01). The three-way interaction was plotted in Fig. 1. As shown in Fig. 1, the pattern is consistent with a reinforcement or synergistic interaction relationship, suggesting that configural cue processing is present in decisions of job applicants. We also conducted simple slope tests using software developed by Preacher et al. (2006). Results showed that the positive association between economic responsibility and probability of accepting offer was significant for all four combinations of legal and ethical responsibility. As we expected, however, the association was strongest when both legal and ethical responsibilities were high (simple slope = 23.19, t = 18.16, p < .001) and weakest when both legal and ethical responsibilities were low (simple slope = 11.35, t = 12.17, p < .001).

Between-Subjects Analyses

To test the moderating effects of individual ethical predispositions on the relationship between CSR and applicant attraction to organizations, the intercepts and the level-1 slope coefficients for economic, legal, and ethical responsibility cues were regressed on the two ethical predispositions variables—utilitarianism and formalism.

Hypothesis 3a predicted that the relationship between economic aspect of CSR and organizational attraction would be stronger for strong utilitarians than for weak utilitarians. As can be seen in Table 5, Hypothesis 3a was not supported in the equation of economic responsibility, where utilitarianism was not significantly associated with variance in within-subjects slope for either outcome. However, contrary to our expectation, in the equation of ethical responsibility, utilitarianism was found to be significantly and negatively associated with variance in slope for perception of organizational attraction (γ31 = −.15, p < .01) and for probability of accepting offer (γ31 = −2.64, p < .01).

Hypothesis 3b and 3c predicted that the relationship between legal and ethical aspects of CSR and organizational attraction would be stronger for strong formalists than for weak formalists. In the equation of economic responsibility, formalism was not significantly associated with the variance in within-subjects slope for either outcome. In the equation of legal responsibility, formalism was significantly and positively associated with slope variance for perception of organizational attraction (γ22 = .17, p < .01) and for probability of accepting offer (γ22 = 2.95, p < .01). Finally, in the equation of ethical responsibility, formalism was significantly and positively associated with slope variance for perception of organizational attraction (γ32 = .16, p < .01) and probability of accepting offer (γ32 = 2.63, p < .01). Thus, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

The R 2 at level 1 and level 2 was also calculated following Luke’s (2004) recommendations. R 2 at level 1 and level 2 assesses the percentage reduction in level-1 and level-2 variance by including level-1 and level-2 predictors, respectively. The results show that the amount of within-subjects variance explained by the three cue variables was 51% for attraction perception and 46% for probability of accepting offer. The two individual ethical predisposition variables explained 4.1% of the between-subject variance in attraction perception and 5.0% in probability of accepting offer. The substantial unexplained between-subjects variance suggested that other individual differences may be relevant in explaining variation across decision makers.

Study 2—Methods

Study 2 was designed to test the main effects of the three aspects of CSR and pay level as well as the interactive effects of economic, legal, and ethical performance on job applicants’ decision making. In addition, it tested the moderating effects of individual differences in ethical predispositions and Machiavellianism.

Subjects and Procedure

Participants included 66 undergraduate business students approaching graduation at a northeastern university. The mean age of respondents was 23.7 (SD = 6.15). Across the sample, the race-ethnicity breakdown was 68% Caucasian, 3% African-American, 17% Asian-American, and 12% other. Men comprised 46% of the sample, and the mean work experience was 6.64 years (SD = 6.23). The majority of the participants (67%) were currently in the job market looking for a job. Among those who were not actively seeking a job, they were either employed already or going to look for a job in the following year.

The general procedure for study 2 was similar to that described for study 1. Respondents received a packet containing the scenarios, a series of questions designed to assess their decisions, and individual information questionnaire.

Scenario Descriptions

In Study 2, the three CSR cue variables and pay level were manipulated. We revised the descriptions of the low and high levels of CSR variables in study 1 to ensure that each manipulated CSR variable was the only variable across different levels and everything else was held constant. This resulted in shorter and simpler scenarios. Pay level was manipulated by providing information on whether the pay for current position was below industry average, average, or above industry average. Each of the manipulations is listed in Table 6. We conducted a pilot study among 23 business students to determine whether the manipulated cue levels generated the desired perceptions of low and high levels of each aspect of CSR. The respondents were instructed to categorize the descriptions on the basis of whether they describe a company’s economic, legal, or ethical performance. After categorizing, they were asked to rank the companies in each category for their corporate social responsibility from high to low. All respondents correctly identified the CSR variables and differentiated the different levels of each CSR variable.

A fully crossed factorial design was used to create 24 scenarios (2 × 2 × 2 × 3). Three random scenarios were replicated to assess test–retest reliability, bringing the total number of scenarios to 27. The average correlation coefficient was .75 for attraction to organization and .73 for probability of accepting offer. In addition, cue order within the scenarios and the order in which the 27 scenarios were placed varied across subjects.

Individual Difference Variables

Machiavellianism was measured with Christie and Geis’s (1970) 20-item Mach IV scale. Sample items include, “It is hard to get ahead without cutting corners here and there,” and “One should take action only when sure it is morally right” (reverse coded). The reliability of this measure was .77. The measures of utilitarianism (α = .76) and formalism (α = .71) were the same as used in study 1.

Dependent Variables

The measures of perception of organizational attraction and probability of accepting offer were the same as used in study 1 as well. The Cronbach’s alpha was .98 for attraction perception.

Study 2—Results

We first fit the null, unconstrained model using HLM. The results of the null model were then used to calculate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). The ICCs were 7.1% and 10.7%, indicating that about 7% of the variance in attraction perception and 11% of the variance in probability of accepting offer were between individuals (Table 7).

Within-Subjects Analyses

Table 8 shows the results of the random coefficient model with the three CSR cues and pay level as level-1 predictors and the two outcome variables as level-1 dependent variables. There were no level-2 predictors in this model. All level-1 predictors were significantly positively related to attraction perception (γj0 range between .77 and 1.77) and probability of accepting offer (γj0 range between 12.68 and 27.93). Therefore, Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c were supported.

Within-Subjects Interaction Effects

We used SAS Proc Mixed to test the two-way and three-way interactive effects of CSR variables and pay level.Footnote 1 The results are presented in Table 9. We only interpreted the highest-order significant interactions, as suggested by Aiken and West (1991). We found that the three-way interaction between CSR variables was significant for attraction perception (β = .32, p < .05). The three-way interaction is plotted in Fig. 2, which shows that the combination of high responsibility in all aspects of CSR leads to higher attraction perception than would be obtained with any other combination. The pattern supported Hypothesis 2 regarding the presence of configural cue processing in job applicants’ decision making. Furthermore, the simple slope tests revealed that the positive association between economic responsibility and applicant attraction was strongest when both legal and ethical responsibilities were high (simple slope = 1.37, t = 10.21, p < .001). In contrast, economic responsibility was not significantly associated with applicant attraction when both legal and ethical responsibilities were low (simple slope = 0.29, t = 1.91, n.s.).

Although we did not offer specific hypotheses, we did expect that pay level might interact with CSR variables in influencing job applicants’ decision making. We found that the two-way interactions between pay and legal responsibility and between pay and ethical responsibility were significant for probability of accepting offer (β = 2.29, p < .05 & β = 2.56, p < .01). The results are plotted in Fig. 3. As shown in Fig. 3, pay level was positively associated with applicant attraction for both low and high levels of legal responsibility. However, the slope was steeper when legal responsibility was high than when it was low. Similarly, the positive relationship between pay level and applicant attraction was stronger for high than for low ethical responsibility. Together, these results indicate that high legal and ethical responsibility accentuated the positive association between pay level and applicant attraction.

Between-Subjects Analyses

The intercepts-and-slopes-as-outcomes model was fitted to test the moderating effects of Machiavellianism and individual ethical predispositions on the relationship between CSR and applicant attraction. As indicated in Table 10, neither Machiavellianism nor utilitarianism was significantly related to the attraction outcomes in the equation of economic responsibility, and thereby failed to support Hypotheses 3a and 4a. Hypothesis 3b was supported in the equation of legal responsibility, where formalism was significantly and positively associated with variance in the within-subjects slope for attraction perception (γ23 = .31, p < .05) and probability of accepting offer (γ23 = 6.35, p < .01). We also found negative association between Machiavellianism and slope variance for both attraction outcomes (γ21 = −.19, p < .10 & γ21 = −3.48, p < .05), supporting Hypothesis 4b. In the equation of ethical responsibility, formalism was significantly and positively associated with variance in slope for both outcomes, supporting Hypothesis 3c (γ33 = .58, p < .01 & γ33 = 7.77, p < .01). Results also supported Hypothesis 4c. Machiavellianism was found to be negatively associated with the slope variance (γ31 = −.21, p < .10 & γ31 = −4.45, p < .05). An unexpected finding was the negative association between utilitarianism and variance in slope for both outcomes (γ32 = −.28, p < .05 & γ32 = −5.36, p < .05). Finally, although not formally hypothesized, we also expect that individual ethical predispositions and Machiavellianism would moderate the relationship between pay level and applicant attraction. In the equation of pay level, Machiavellianism was found to be significantly and positively associated with slope variance for attraction perception (γ41 = .23, p < .01) and probability of accepting offer (γ41 = 4.32, p < .001). Contrary to our expectations, however, utilitarianism was not significantly associated with variance in within-subjects slope for either outcome.

The R 2 at level 1 and level 2 was also calculated. The results showed that the amount of within-subjects variance explained by the CSR variables and pay level was 60% for attraction perception and 57% for probability of accepting offer. There was a marked increase in level-2 R 2 compared with study 1. Individual differences in Machiavellianism and ethical predispositions explained 27.5% of the between-subject variance in attraction perception and 23% in probability of accepting offer.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to explore the mechanism through which corporate social responsibility (CSR) influences job applicants’ attraction to organizations using a policy-capturing design. In general, the results showed support for the proposed relationships. Each component of CSR had an independent relationship with applicant attraction. Further, the participants combined CSR information in an interactive configural manner. In addition, applicants with different ethical predispositions and Machiavellian personality type were affected by the CSR message to different extents. The pattern of the interactions was generally consistent with expectations; however, there were some exceptions.

The Effects of CSR on Applicant Attraction to Organizations

Consistent with previous research, the present study adds new evidence to the growing body of knowledge that suggests that socially responsible companies are more attractive employers than less socially responsible companies. It is, however, the first study of which we are aware wherein multiple aspects of CSR were examined in a single study. Though previous researchers have examined the relationship between specific social policies and applicant attraction, their findings cannot be generalized to the association between general CSR aspects and applicant attraction. The present study extends this line of research by more fully exploring the relationship between CSR and applicant attraction, with CSR encompassing economic, legal, and ethical responsibility. The results in both studies supported the hypotheses, suggesting that when considered simultaneously, all three types of CSR had an important and independent relationship with perception of organizational attraction and probability of accepting an offer. They indicate that job applicants can distinguish among different types of CSR in their decision-making process.

Configurality of CSR

Beyond the main effects of the CSR cues, we found a strong multiplicative relationship among the three CSR cues. The three-way interaction plots in both studies show a similar pattern. As we expected, the slopes of the regression lines were relatively flat when both legal and ethical responsibilities were low. When either legal or ethical responsibility was high, there was a positive relation between economic responsibility and applicant attraction (i.e., when low legal responsibility was offset by high ethical responsibility or when low ethical responsibility was offset by high legal responsibility). By comparison, the relationship was strongest at high levels of both legal and ethical responsibility. This finding suggests that a bad reputation may diminish the positive relationship between corporate economic performance and applicant attraction. Job applicants seem to be hesitant to pursue jobs at companies that fall short of their legal and ethical responsibilities, regardless of the level of economic responsibility (as shown in Study 2). This finding is consistent with signaling theory that job applicants interpret whatever information they receive as “signals” of the organizations’ working conditions (Spence 1974). A company’s commitment to its legal and ethical responsibilities (or lack thereof) can send signals about what it is like to work in the firms by denoting certain organizational values and norms (Greening and Turban 2000). Thus, job applicants may not be attracted to companies with low legal and ethical performance, even when tempted by lucrative offers from financially strong companies.

An intensification or synergistic effect was present, whereby the combination of high levels of responsibility across all aspects of CSR led to highest attraction. In addition, the three-way interaction effect reflects inherently compensatory processing. That is, the subjects make trade-offs between various CSR attributes such that strengths in one attribute compensate for weaknesses in another. It suggests that job applicants make moral trade-offs when they consider information pertaining to CSR. This result is consistent with socially responsible investing and consumer behavior research showing that investor and consumer decisions are often infused with moral trade-offs between different packages of information (e.g., De Pelsmacker et al. 2005; Glac 2009). The finding also cautions against analyzing corporate economic, legal, and ethical responsibility individually, because the manner in which any single aspect operates may depend on the full constellation of CSR. Thus, it gives credence to Schwartz and Carroll’s (2003) suggestion that corporate social responsibility portraits might be developed to reflect the extent of interaction among the various domains of CSR in different contexts.

It is noteworthy that the study 2 results showed that the two-way interactions between pay level and CSR aspects were statistically significant. This finding speaks to the relative importance of legal and ethical responsibility in applicant attraction compared to other job factors such as starting salary. It suggests that CSR still matters when the financial factors are taken into consideration. Despite the importance of monetary compensation in influencing applicant attraction, low legal and ethical performance dampened the positive relation between pay level and applicant attraction. Indeed, Chapman et al. (2005) found in their meta-analysis that pay predicted job pursuit intentions to a much lesser extent than organizational image. Our finding suggests that organizational image not only influences applicant attraction directly but also moderates the relation between pay and applicant attraction. We acknowledge, however, that there is a difference between reported attraction perception and intention and actual job choice. In reality, attributes involving monetary values, such as monetary payoff, loom larger than those attributes that are not easy to evaluate independently, such as CSR information, especially when decision makers evaluate multiple options comparatively (Hsee et al. 1999). That is, job applicants may choose a high-paying job in a low-CSR company over a low-paying job in a high-CSR company, because they feel they should not pass up an opportunity to make more money.

The Moderating Effect of Individual Differences to CSR

Adopting a P-O fit perspective, we investigated whether individual differences in ethical predispositions and Machiavellianism functioned as moderators in the relationship between CSR and applicant attraction. Most of the fit hypotheses were supported. As predicted, strong formalists gave larger weight to the legal and ethical aspect of CSR such that they were more attracted to companies high in these regards than were weak formalists. This result supports the basic proposition of P-O fit theory, suggesting that job-choice decisions are ethics-laden. That is, applicants’ choice of employers mirrors their own ethical frameworks. Also as predicted, high Machs were less attracted to companies with high legal and ethical performance. This result corroborates previous findings that high Machs tend to be more successful than their low Machs counterparts in loosely structured organizations, where high Machs have opportunities to exploit the situation and others for personal gains (Christie and Geis 1970; Schultz 1993). Consequently, it is reasonable to expect that high Machs self-select into organizations that are devoid of clearly defined rules and regulations.

Unexpected results found in the within-subjects analysis warrant further discussion. For example, it was found that strong utilitarians were not more attracted to companies high in the economic aspect of CSR than were weak utilitarians, nor were they more attracted to companies that offer relatively high pay. Considering the high stakes involved (e.g., job security, pay), it makes sense that weak utilitarians care as much as strong utilitarians about the financial condition and monetary compensation at the employing organizations. Another surprising finding is that strong utilitarians were greatly influenced by the ethical aspect of CSR such that ethical companies were less attractive to strong utilitarians than to weak utilitarians. It suggests that strong utilitarians view corporate investment in discretionary, ethical activities negatively. A possible explanation might be that in the minds of strong utilitarians, the economic aspect and ethical aspect of CSR are competing claims over corporate resources. For strong utilitarians, using corporate resources to promote socially responsible activities, especially beyond the realm of obeying the law, would result in additional costs that put a company at an economic disadvantage compared to others.

It is interesting to note that high Machs were particularly attracted to companies that pay well, although they acted indifferently than low Machs toward corporate economic performance. This notion has implications for understanding the dispositional differences between high and low Machs. Prior work has shown that high Machs are inclined to focus on explicit, cognitive definitions of the situation and concentrate on strategies for winning, while low Machs tend to get distracted by emotional involvement, social pressure, and other factors irrelevant to winning (Christie and Geis 1970). Our study further demonstrated high Machs’ clear goal focus, as evidenced by their greater desire for high pay, a primary goal set by most job seekers. In contrast, low Machs may base their job choice decisions on factors that have no direct bearing on their self-interest.

Limitations and Future Research

One limitation of the study is the use of student samples, especially those who were not currently seeking a full-time job, raising questions about the external validity of the present study. To address this concern, we repeated the analyses on the subgroup of participants who reported that they were currently seeking full-time job in study 2 (n = 44). The results, which are available upon request from the first author, were similar to those reported using the full sample. These post hoc findings suggest that our full sample is prototypic and possesses the essential characteristics of college-educated, entry-level job seekers. Nevertheless, given the characteristics of our sample, our findings should be interpreted cautiously, until they can be replicated in different populations of job applicants in future research.

Second, with the use of a policy capturing design, our organizational characteristic manipulations did not reflect all of the information applicants may obtain about organizations and jobs. Future research should extend our findings to field settings. For example, an empirical study can be designed to assess job applicants’ attraction and pursuit intentions and CSR perceptions about relevant companies with which they would potentially interview. Should the results be replicated in a field study, the external validity of the present study would be strengthened.

Third, this study is predicated on the assumption that job applicants have access to the CSR information. This study is not informative with respect to how often information about CSR is available to job seekers, or how often CSR information presented by recruiting organizations is salient to job seekers. However, the possibility that organizations may not inform applicants of their CSR does not negate the possibility that CSR could affect job seekers’ decisions if such information is revealed. In fact, in the absence of the information provided by employing organization, applicants may proactively look for it elsewhere, e.g., through word of mouth (Cable et al. 2000) or on the Internet. Future research needs to address the extent to which CSR information is sought by job applications, its salience to them, and the implications of that salience for job choices.

Fourth, although Carroll’s (1979) conceptualization of CSR was supported in this study, future research can be based on other models. For example, Swanson (1995) argued that Carroll’s CSR principles lack normative clarity as they do not address a firm’s moral motivation for being socially responsible. It is not clear whether they act on the threat of social control and coercion or a positive commitment to society that disregards self-interest. Therefore, future research would benefit from value-based CSR conceptualization. In the recruitment context, we expect that job applicants’ belief of the recruiting organization’s moral motives of CSR would not only influence their attraction perception and pursuit intentions directly but also moderate the impact of the actual social performance.

Lastly, given the large proportion of unexplained variance across decision makers found in this study, future research should consider other individual characteristics that may moderate the CSR—applicant attraction relationship. A good starting point may be further examination of individual values and personality characteristics such as conscientiousness. Further, the levels of job choices may influence the impact of CSR on applicant attraction such that applicants with relatively few interviews would not have the privilege to screen companies based on their CSR (Greening and Turban 2000).

Practical Implications

The results of this research also have practical implications. This study focuses on a different stakeholder group from most other CSR studies—job applicants and examines whether firms may benefit from socially responsible actions from the recruitment perspective. That is, CSR may be a source of competitive advantage by attracting quality employees. As managers justify their investment decisions in their firms’ social responsibilities, they may wish to take into consideration the values accrued as such. Thus, this research may provide practitioners with a better understanding of the potential competitive advantage afforded by CSR, especially as they seek entry-level employees who have been exposed to CSR concepts in their university curriculum.

To the extent that applicants with certain ethical predispositions and personalities are more interested in organizations with certain CSR characteristics, organizations may be able to maximize the utility of their CSR investments by selectively conveying CSR information in recruitment brochures and on their web sites that are attractive to their ideal applicants. Companies may mold their “good citizen” reputation to attract more rule-abiding, ethically conscientious applicants. Nevertheless, such information may be less useful in influencing aggressive, results-oriented job applicants’ job choice decision.

It is also important for recruiting organizations to become aware of job applicants’ implicit policies. Our results suggest that job applicants evaluate CSR information in a compensatory fashion. This information processing model may give managers an opportunity to influence applicant attraction by manipulating the salience of particular types of CSR in recruitment brochures. For example, a company that cannot afford to provide high pay to attract employees may find that focusing on their CSR activities in their recruitment materials gives them a competitive advantage in the recruitment space. Doing so would help a company reap the full benefits of its CSR program.

Notes

In our original model, we included all possible two-way and three-way interaction terms involving CSR variables and pay level. For the sake of parsimony, however, we dropped all non-significant three-way interaction terms and reran a reduced model.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Aiman-Smith, L., Bauer, T. N., & Cable, D. M. (2001). Are you attracted? Do you intend to pursue? A recruiting policy-capturing study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16, 219–237.

Aupperle, K. E., Carroll, A. B., & Hatfield, J. D. (1985). An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 28, 446–463.

Barber, A. E. (1998). Recruiting employees. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Bass, K., Barnett, T., & Brown, G. (1999). Individual difference variables, ethical judgments, and ethical behavioral intentions. Business Ethics Quarterly, 9, 183–205.

Bauer, T., & Aiman-Smith, L. (1996). Green career choices: The influence of ecological stance on recruiting. Journal of Business and Psychology, 10, 445–458.

Behrend, T. S., Baker, B. A., & Thompson, L. F. (2009). Effects of pro-environmental recruiting messages: The role of organizational reputation. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24, 341–350.

Benson, J., & Clark, F. (1982). A guide for instrument development and validation. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 36, 789–800.

Brady, F. N. (1985). A Janus-headed model of ethical theory: Looking two ways at business/society issues. Academy of Management Review, 10, 568–576.

Brady, F. N., & Wheeler, G. E. (1996). An empirical study of ethical predispositions. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 927–940.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. (2009). Employment projections: 2008–2018. Retrieved December 1, 2011, from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/ecopro.nr0.htm.

Cable, D. M., Aiman-Smith, L., Mulvey, P. W., & Edwards, J. R. (2000). The sources and accuracy of job applicants’ beliefs about organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 1076–1085.

Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1994). Pay preferences and job search decisions: A person-organization fit perspective. Personnel Psychology, 47, 317–348.

Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person-organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67, 294–311.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 4, 497–505.

Chapman, D. S., Uggerslev, K. L., Carroll, S. A., Piasentin, K. A., & Jones, D. A. (2005). Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 928–944.

Chatman, J. A. (1991). Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 459–484.

Christie, R., & Geis, F. (1970). Studies in Machiavellianism. New York: Academic Press.

Clarkson, M. B. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20, 92–117.

Davis, K. (1973). The case for and against business assumption of social responsibilities. Academy of Management Journal, 16, 312–322.

De Pelsmacker, P., Driesen, L., & Rayp, G. (2005). Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39, 363–385.

Ehrhart, K. H., & Ziegert, J. C. (2005). Why are individuals attracted to organizations? Journal of Management, 31, 901–919.

Einhorn, H. J. (1971). Use of nonlinear, noncompensatory models as a function of task and amount of information. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6, 1–27.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 233–258.

Gatewood, R. D., Gowan, M. A., & Lautenschlager, G. J. (1993). Corporate image, recruitment image, and initial job choice decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 414–427.

Glac, K. (2009). Understanding socially responsible investing: The effect of decision frames and trade-off options. Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 41–55.

Goldberg, L. R. (1971). Five models of clinical judgment: An empirical comparison between linear and nonlinear representations of the human inference process. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 6, 458–479.

Graham, M. E., & Cable, D. M. (2001). Consideration of the incomplete block design for policy-capturing research. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 26–45.

Greening, D. W., & Turban, D. B. (2000). Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Business & Society, 39, 254–280.

Hegarty, W. H., & Sims, H. P. (1978). Some determinants of unethical decision behavior: An experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 63, 451–457.

Hitt, M. A., & Barr, S. H. (1989). Managerial selection decision models: Examination of configural cue processing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 53–61.

Hoffman, P. J. (1960). The paramorphic representation of clinical judgment. Psychological Bulletin, 57, 116–131.

Hoffman, P. J., Slovic, P., & Rorer, L. G. (1968). An analysis-of-variance model for the assessment of configural cue utilization in clinical judgment. Psychological Bulletin, 69, 338–349.

Hofmann, D. A., & Gavin, M. B. (1998). Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: Implications for research in organizations. Journal of Management, 24, 623–641.

Hsee, C. K., Lowenstein, G. F., Blount, S., & Bazerman, M. H. (1999). Preference reversals between joint and separate evaluations of options: A review and theoretical analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 576–590.

Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (1997). Applicant personality, organizational culture, and organizational attraction. Personnel Psychology, 50, 359–394.

Keeney, R. L., & Raiffa, H. (1976). Decisions with multiple objectives: Preferences and value trade-offs. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Press.

Klaas, B. S., Mahony, D., & Wheeler, H. N. (2006). Decision-making about workplace disputes: A policy-capturing study of employment arbitrators, labor arbitrators, and jurors. Industrial Relations, 45, 68–95.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Jansen, K. J., & Colbert, A. E. (2002). A policy-capturing study of the simultaneous effects of fit with jobs, groups, and organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 985–993.

Lievens, F., & Highhouse, S. (2003). The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company’s attractiveness as an employer. Personnel Psychology, 56, 75–102.

Luke, D. A. (2004). Multilevel modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mellers, B. A. (1980). Configurality in multiple-cue probability learning. American Journal of Psychology, 93, 429–443.

Morrison, E. W., & Vancouver, J. B. (2000). Within-person analysis of information seeking: The effects of perceived costs and benefits. Journal of Management, 26, 119–137.

O’Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, M. M. (1991). People and organizational culture: A Q-sort approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31, 437–448.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rotundo, M., & Sackett, P. R. (2002). The relative importance of task, citizenship, and counterproductive performance to global ratings of job performance: A policy capturing approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 66–80.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40, 437–453.

Schultz, C. J. (1993). Situational and dispositional predictors of performance: A test of the hypothesized Machiavellianism X structure interaction among sales people. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 478–498.

Schwartz, M., & Carroll, A. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: A three-domain approach. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13, 503–530.

Sethi, S. P. (1979). A conceptual framework for environmental analysis of social issues and evaluation of business response patterns. Academy of Management Review, 4, 63–74.

Simon, H. A. (1951). A formal theory of the employment relationship. Econometrica, 19, 293–305.

Sims, R. L., & Keon, T. L. (1997). Ethical work climate as a factor in the development of person-organization fit. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 1095–1105.

Singhapakdi, A., & Vitell, S. J. (1990). Marketing ethics: Factors influencing perceptions of ethical problems and alternatives. Journal of Macromarketing, 12, 4–18.

Smith, W. J., Wokutch, R. E., Harrington, K. V., & Dennis, B. S. (2004). Organizational attractiveness and corporate social orientation: Do our values influence our preference for affirmative action and managing diversity? Business and Society, 43, 69–96.

Spence, A. M. (1974). Market signaling: Information transfer in hiring and related screening processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Swanson, D. L. (1995). Addressing a theoretical problem by reorienting the corporate social performance model. Academy of Management Review, 20, 43–64.

Tang, T. L., & Chen, Y. (2008). Intelligence vs. wisdom: The love of money, Machiavellianism, and unethical behavior across college major and gender. Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 1–26.

Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1996). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 658–672.

Turban, D. B., & Keon, T. L. (1993). Organizational attractiveness: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 184–193.

Turban, D. B., Lau, C., Ngo, H., Chow, I. H. S., & Si, S. X. (2001). Organizational attractiveness of firms in the People’s Republic of China: A person-organization fit perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 194–206.

Victor, B., & Cullen, J. B. (1988). The organizational bases of ethical work climates. Administrative Science Quarterly, 33, 101–125.

Wartick, S. L., & Cochran, P. L. (1985). The evolution of the corporate social performance model. Academy of Management Review, 10, 758–769.

Williams, M., & Bauer, T. (1994). The effect of managing diversity policy on organizational attractiveness. Group and Organization Management, 19, 295–308.

Wilson, D. S., Near, D., & Miller, R. R. (1996). Machiavellianism: A synthesis of evolutionary and psychological literatures. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 285–299.

Winter, S., Stylianou, A., & Giacalone, R. (2004). Individual differences in the acceptability of unethical information technology practices: The case of Machiavellianism and ethical ideology. Journal of Business Ethics, 54, 275–296.

Wood, D. J. (1991). Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of Management Review, 16, 691–718.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Gowan, M.A. Corporate Social Responsibility, Applicants’ Individual Traits, and Organizational Attraction: A Person–Organization Fit Perspective. J Bus Psychol 27, 345–362 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9250-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9250-5