Abstract

The interconnected relationships between a business and its various stakeholders have been the beneficiaries of widespread research over the past few decades. Consequently, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and organizational justice have gained much prominence within management and organizational research. Yet, there remains less visibility into how they may interact to influence employee attitudes. Combining insights from social exchange and social identity theories, we develop and validate a mediated moderation model: organizational identification’s mediation accounts for the interactive effect of ethical CSR (i.e., perceptions of whether firms act according to the generally accepted norms, standards, and principles of society) and interactional justice (i.e., perceptions of equity in the relationship between employees and those with authority over them) on employee job satisfaction. Using structural equation modeling on a sample of 293 employees, we find support for our proposed relationships. This research contributes to the existing knowledge at the intersection of CSR and organizational justice literature and reveals useful takeaways germane to accruing ethical capital with employees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Increasingly, organizations aspire to be good corporate citizens by demonstrating responsible stewardship toward the collective well-being of their stakeholders. This brings their practice of instilling ethical values in their management and core decision-making processes into sharper focus. Business practices are enduring unprecedented scrutiny in terms of how they address social demands and the needs of the wider society in which they exist — rankings such as Business Ethics Magazine’s ‘100 Best Corporate Citizens’, Forbes’ ‘World’s Most Reputable Companies’, and Fortune’s ‘World’s Most Admired Companies’ are a testament to this. The Business Roundtable released a statement, signed by a group of prominent CEOs, which included a stated goal of repurposing business to elevate the concerns of other constituencies above those of shareholders (Harrison et al., 2020). Taken together, these high-level observations serve to underline the importance of the ethical aspect of governance.

The extent to which an organization embarks on creating value for all stakeholders is also of increasing salience to employees—a key internal stakeholder. Today, employees are socially conscious and expect their organizations to exhibit a sense of social awareness, compassion, and transparency, as well as to conform to socially constructed and morally accepted values and principles (Zheng, 2020). Furthermore, research indicates that employees feel a moral obligation to uphold the societal norms of fairness and are concerned about whether their organization treats all stakeholders equitably and ethically (e.g., Cropanzano et al., 2003; Cropanzano, Massaro, & Becker, 2017). One prominent question is how the required compliance with initiatives of shared values in a firm’s business practices may influence important employee work-related attitudes.

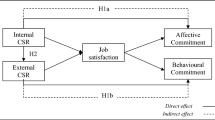

Toward that end, our contribution is to develop a systematic theory and provide empirical evidence that (1) employee perceptions of ethical corporate social responsibility (CSR), a range of discretionary initiatives in the spirit of doing what is right, just, and fair (Schwartz & Carroll, 2003), comprises an antecedent of organizational identification, defined as the extent to which individuals perceive oneness with the organization (Ashforth & Mael, 1989); (2) interactional justice, the perceived fairness of social exchanges between employees and their supervisors (Bies & Moag, 1986), positively moderates this link; and (3) the mediating role of organizational identification is the key mechanism that accounts for the interactive effect of ethical CSR and interactive justice on the focal employee outcome—job satisfaction. We blend insights from social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) and social identity theory (e.g., Tajfel & Turner, 1979)—two interrelated streams of literature—to guide our theorizing as they provide a comprehensive social framework for explaining individual behaviors in organizational settings. To empirically test our proposed model, we utilize survey data obtained from 293 respondents sampled from a broad cross section of employees.

This article contributes to both theory and practice. Foremost, our work extends the emerging literature at the intersection of CSR and justice (e.g., Rupp et al., 2006). As a novel point not evidenced in prior studies, the current endeavor is the first to bridge the ethical CSR and interactional justice domains. Table 1 displays the most relevant literature overview to better annotate the positioning and contribution of our research. Specifically, we argue and furnish evidence that interactional justice places a boundary condition on the positive influences of ethical CSR on organizational identification. Second, based on our findings from our mediated moderation model, we propose that the extent to which people self-stereotype as members of an organization transmits this interactive effect on job satisfaction. That is, we depict organizational identification as a mediation mechanism. For practitioners, the knowledge of more intricate linkages among ethical CSR, interactional justice, and organizational identification is more actionable. The positive interaction effect between ethical CSR and interactional justice can be broadly contextualized as an effective managerial lever: the implication is that a commitment to ethical CSR will be empowered through a “human component” by way of interactional justice. Firms must endeavor deeply to nurture an atmosphere in which management and employees can share a high-quality interpersonal communication at all levels. As our mediated moderation results suggest, the overarching sense of belongingness or a unity of purpose among employees, in essence, will be a catalyst for positive work-related outcomes.

Theoretical Background

Ethical CSR

Ethical CSR comprises a firm’s moral code of conduct, through which it transcends its greater purpose and attends to societal needs and goals—going beyond its explicit transactional interests (e.g., Barnett et al., 2020). At the heart of ethical CSR is the normative reasoning of “doing good to do good” (Vogel, 2005, pp. 20–21. Even within its systematic constraints (de Bakker et al., 2020), CSR research along with the practice thereof continue to evolve and inform our understanding of a firm’s broader ethical obligation to society (Carroll, 2021) as well as the strategic role of ethical CSR in the realm of the shared values between business and society (Porter & Kramer, 2011).

In this regard, a pivotal development pertains to emphasizing an element of governance quality. This includes concerns for protecting human rights and equality, as well as taking stakeholders’ expectations of accountability, transparency, and disclosure into consideration. Two common themes underlie a firm’s ethical CSR initiatives: a fair labor policy for employees and fair trade practices for suppliers. Fair labor practices ensure the well-being and support of a firm’s employees, including fair wages and benefits, non-discrimination policies, career advancement opportunities, and improved working conditions (e.g., workplace cleanliness, lighting and ventilation, toilet and changing facilities, and on-site health care). For instance, along with the comprehensive health coverage provided to its employees, Starbucks provides a diverse set of perquisites, such as stock and savings options, paid vacation time, parental leave, and onsite gym, daycare and dry-cleaning (Starbucks, 2022). Fair trade for suppliers concerns the eradication of labor exploitation by ensuring that those in the supply chain are being treated equitably and paid fairly, and that sustainable practices are embraced in the upstream supply chain. For example, Ben & Jerry’s Ice Cream has been a prominent proponent to further a socially based purpose and uses ethically sourced fair trade-certified ingredients, such as vanilla, coffee, sugar, and bananas. Extant CSR-related research has recognized the ethical domain of CSR (e.g., Kim, Millman, & Lucas, 2021; Schwartz & Carroll, 2003). For example, in a study that examines Argentina’s mining industry, ethical CSR has emerged as the second most important CSR dimension (Yakovleva & Vazquez-Brust, 2012).

Interactional Justice

Interactional justice represents the perceptions of those on the receiving end of the fairness of their treatment by upper management or others who control resources or rewards (Bies, 2001; Bies & Moag, 1986).Footnote 1 Understanding how interactional justice impacts employee attitudes has been the subject of considerable academic attention (e.g., Ahmad, 2018; Bies & Shapiro, 1987; Chiaburu, 2007; Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2001). Interactional justice is characterized by the two subcomponents of informational justice (i.e., the accuracy and adequacy of received information) and of interpersonal justice (i.e., the quality of interpersonal interactions) (Colquitt et al., 2001). Supervisors who exercise informational justice will truthfully and clearly explain procedures that impact employee outcomes so that employees can properly contextualize their workplace (Patient & Skarlicki, 2010). Supervisors demonstrate interpersonal justice by providing subordinates with respect and propriety, being polite, attentive, and sincere with them, and also, by refraining from making prejudicial statements when interacting with them (Cropanzano et al., 2002). As the elements of interactional justice are prevalent in the day-to-day work environment of employees, this form of justice has long been recognized as a critical construct in organizational behavior, affecting employee’s work-related attitudes (e.g., Au & Leung, 2016).

Organizational Identification

Organizational identification refers to the “perception of oneness with or belongingness to an organization, where the individual defines him or herself in terms of the organization(s) in which he or she is a member” (Mael & Ashforth, 1992, p. 104). Central to this notion is the idea that being a member of an organization can become—at least in part—an important element of how employees see themselves. The concept of organizational identification is rooted in identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) and an important aspect of this construct is that it involves the individual having “perceived him or herself as psychologically inter-twined with the fate of the group” (Mael & Ashforth, 1989; p. 21). Considerable research has indicated that the magnitude of employees’ psychological linkage to the organization is highly relevant to desirable attitudes and behaviors toward the organization, such as employees’ willingness to commit themselves to the organization (e.g., Lee et al., 2015; Olkkonen & Lipponen, 2006). In sum, organizational identification is a key component of the overall representation of the employee-organization relationship.

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction refers to a positive emotional state stemming from an assessment of one’s job or job experience (Alegre et al., 2016; Locke, 1976). In essence, it constitutes a positive attitude based on the employee’s perceptions of the physical and social circumstances of their job, such as salary and benefits, level of job ambiguity, organizational practices, and quality of supervision and social relationship. It is well-established that job satisfaction is a crucial factor in an employee’s life and, as such, much of the work in organizational psychology (Judge et al., 2002; Vendenberg & Lance, 1992) has viewed job satisfaction as having an inherently positive influence on retaining qualified and competent employees, which is in turn a critical driver of organizational success. Thus, it is not surprising that researchers have shown a renewed interest in identifying different combinations of antecedents that may affect job satisfaction (Alegre et al., 2016).

Hypothesis Development

Ethical CSR and Organizational Identification

Ethical CSR involves making decisions with outcomes justly affecting the firm’s stakeholders. The literature has documented that employees use such initiatives as a lens through which they may assess organizational practices and procedures with ethical content (e.g., De Roeck et al., 2014). An organization represents an important reference group for employees and, according to social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979), such group identification can enhance an individual’s self-esteem. Drawing from this precept, an organization investing in ethical CSR to “do good” for the wider society is perceived as prestigious and distinctive and will afford its employees a deep-seated self-definitional need (Dutton et al., 1994). To illustrate, when a firm’s commitment to social good exceeds the minimum threshold of stakeholder expectations, employees will feel more fulfilled and will believe they are performing activities that can scale to a meaningful impact in the service of a greater good, i.e., beyond the economic elements of a business. By extension, this will have a positive influence on individuals’ perceptions of their social worth and strengthen their organizational identity. All in all, we reason that employees may seek restoration from a socially caring employer with greater reputational capital thus emboldening their organizational identity.

The notion of reciprocity (Blau, 1964), a basic tenet of social exchange theory, can also help explain ethical CSR’s effect on organizational identification. This concept posits that reciprocal behavior occurs as a result of an exchange of activities and resources, both tangible and intangible, between two parties (Gouldner, 1960); that is, when one party voluntarily provides a benefit to another, this action will invoke an obligation in the second party to reciprocate by providing some benefits in return. In our context, through ethical CSR firms support the well-being of their employees and also enable the disparate aspirations of other stakeholders. This leads employees to reciprocate, thereby strengthening the organizational identity. In this vein, a significant stream of literature has emerged indicating a direct, positive relationship between CSR and organizational identification (e.g., Farooq, Rupp, & Farooq, 2017; Ghosh, 2018; Glavas & Godwin, 2013). Thus, ethical CSR should be considered an antecedent to the degree to which employees identify with their organizations. We propose:

Hypothesis 1:

Ethical CSR is positively related to organizational identification.

The Moderating Role of Interactional Justice

Perceptions of interactional justice signal the extent to which a supervisor cares about their employees as well as the degree to which the latter reciprocate by engaging in pro-organizational behavior. In general, prior research recognizes the influence of interactional justice on employee attitudes (e.g., Ambrose et al., 2013; Chiaburu, 2007). Importantly, our investigation looks beyond this established, direct relationship, and treats interactional justice as a contextual variable, which we expect will enhance the positive effects of ethical CSR as described in hypothesis 1. Our rationale for this expectation is rooted in fairness heuristic theory (e.g., Lind, 2001) which postulates that people process information heuristically when they have incomplete or insufficient information. Congruent with this view, employee perceptions regarding the extent to which an organization integrates ethical standards and harmonizes stakeholder interests can be a heuristic device for evaluating that organization. From the employees’ perspectives, the common theme of “doing good for the stakeholders” will manifest in a firm’s ethical CSR initiatives and its practice of interactional justice.

In further support of this view, we draw from the deontic theory wherein the dominant narrative is that employees possess the ethical standards or the duty to guide the moral treatment of others (Cropanzano et al., 2003). In this way, justice is valued for its own sake and not for any direct benefits its exercise may yield (e.g., O’Reilly et al., 2016). Specifically, employees not only account for justice performed for themselves, but they also factor in whether the company adheres to commonly accepted fairness norms in its stakeholder engagements. We argue that employees judge their employer’s propensity to act justly and fulfill stakeholders’ expectations (e.g., ethical CSR and interactional justice) on the basis of their own normative criteria—that is, by staying true to their deon or duty, employees adopt a moral imperative to uphold ethical principles (Folger, 2012). This suggests that employees will react negatively when unfair treatment is rendered to others. In light of these arguments, interactional justice should amplify the positive effect of ethical CSR on employees’ organizational identification. We account for this effect by hypothesizing:

Hypothesis 2:

Interactional justice positively moderates the effect of ethical CSR on organizational identification.

Mediating Role of Organizational Identification

Organizational identity reflects the degree to which an employee integrates the firm’s socially desirable traits into their own self-concept (Dutton et al., 1994). Research has shown that when a firm is perceived as a socially responsible entity, employees are more likely to derive an enhanced self-image from their work for this firm, as well as take pride in the organization, in turn, this will have a positive impact on work attitudes such as job satisfaction (Peterson, 2004). We theorize that the strength of the employees’ organizational identity will serve to explain the interaction effect of interactional justice and ethical CSR on job satisfaction. Social identity theory guides our expectations that employees with a stronger organizational identity will feel that they personally embody organizational values and beliefs (van Knippenberg & Sleebos, 2006). Employees will also emulate and internalize organizational values if they see a good fit between the organization’s values and their own. Consequently, employees with greater organizational identification tend to feel that organizational actions are driven by their own desires and likely will reflect well on them, thus, they will help the organization attain these shared goals.

Ethical CSR and interactional justice constitute salient signals of an organization’s conscience and how well the organization sustains its stakeholders’ interests. As a result, we would expect that, if both initiatives hold true, identifying with the organization will accentuate the group members’ sense of belonging. This notion concurs with prior scholarly insights that when interactional justice is more prevalent, employees navigate the organizational milieu through relationship-building activities with other organizational members and, thereby, enhancing their identification with the organization (Brewer & Gardner, 1996).

Furthermore, organizational identification fuels employees’ psychological investment in their organization. At a granular level, individuals who identify strongly with the firm possess an intrinsic reason to help achieve the organization’s strategic objectives because doing so reflects positively on the organization, and by association, on themselves (Dutton et al., 1994). Consistent with this supposition, a stream of research has affirmed that strong levels of organizational identification will encourage positive thoughts and feelings toward the organization thereby inducing greater work effort and discretionary effort (Lee et al., 2015), which in turn likely will translate into a positive reaction to the individual’s overall job circumstances (e.g., van Dick et al., 2008). With these arguments in mind, organizational identification can be applied as an essential mediator in the effect of the interaction of ethical CSR and interactional justice on employee job satisfaction. In other words, the interaction effect, as it pertains to hypothesis 2, will also exhibit an indirect effect and will be masked in the presence of organizational identification. Taken together, there is a mediated moderation relationship. Formally,

Hypothesis 3:

Organizational identification is positively related to job satisfaction such that organizational identification mediates the interactive effects of ethical CSR and interactional justice on job satisfaction.

Methodology

Research Design and Sampling

We collaborated with two different commercial marketing research firms (based in St. Louis and San Francisco) to obtain the data. Both firms used identical survey instruments and drew their sample populations from their respective respondent pools. Data collection was done sequentially and was separated by an approximately seven-month gap. Our sampling frame consisted of full-time employees (such as executives, managers, vice presidents, and C-level team members). In no case, was more than one respondent from a single firm. To enhance the generalizability of our findings, potential participants were recruited from a range of industry sectors across the USA. The survey instrument contained a cover letter that described our purpose for the study and in which we stated that their participation was voluntary. For both data collection efforts, links to web-based surveys were emailed to respondents, the survey was kept open for three weeks, and a reminder was sent a week before the survey link was disabled.

The merging of two datasets yielded 303 responses of which we removed 10 responses with missing values. Thus, our final sample consisted of 293 respondents (batch 1: 94 and batch 2: 199). Table 2 contains the composition of the sample. We found no significant differences between early and late responses with regard to our focal constructs and controls (p > 0.10), indicating that nonresponse bias was not a serious issue. In addition, we did not find any significant differences across two sets of samples.

Measures

All our constructs were measured by previously established multi-item scales. To assess interactional justice, we used four items developed by Tax et al. (1998). Ethical CSR was captured with five items using the measure employed by Lichtenstein et al. (2004). Organizational identification was measured by four items developed by Mael and Ashforth (1992). Lastly, to measure job satisfaction, we relied on a three-item scale adapted from Hackman and Oldham’s (1975) job diagnostic survey. To minimize model specification and to rule out alternative explanations, we used procedural justice and distributive justice as control variables, employing four items measures for both, taken from Tax et al. (1998). A seven-point scale was applied (with 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) to all constructs. In addition, the model controlled for several individual-level factors, such as age, gender, education, work tenure, job title, position tenure, and three firm-specific factors, namely, firm age, number of employees, and revenues. Table 3 provides the scales for all the study constructs along with their reliability and validity.

Results

Measure Validation

We assessed the psychometric properties of study constructs through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and used the maximum likelihood estimation method with robust standard error in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2011). The model offered a good fit to the data: χ2 (123) = 380.523, p < 0.001; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.924; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.952; and, root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.069. All items loaded substantively were statistically significant (p < 0.01) on their latent factors, and at 0.65 or higher (Table 2). In support of convergent validity, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.84 to 0.95, sufficiently greater than the 0.7 benchmark, and the average variance extracted (AVE) met the minimum cutoff of 0.50. In addition, Loevinger’s H coefficient values for the scales were ≥ 0.3, indicating good scalability (Jansen, 1982).

To assess discriminant validity, we first confirmed that the square root of the AVE exceeded its shared variance (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Next, we conducted a pair-wise comparison of constructs in a series of two-factor confirmatory measurement models. We ran each model first with the correlation between the two constructs constrained to unity, and then with a free estimation of the correlations. Across all comparisons, the Chi-square difference tests supported the discriminant validity of the constructs (p < 0.01). In addition, the composite reliability of our constructs ranged from 0.78 to 0.92 and the AVE for every pair of latent constructs exceeded the squared correlation among the two constructs. The variance inflation factors ranged from 1.07 to 3.52, indicating a minimal threat of multicollinearity. Overall, the preceding fit statistics provided confidence in our model and its estimated coefficients for hypothesis testing and interpretation. Table 4 displays the descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for all the variables.

We undertook several procedural remedies to alleviate the potential concerns associated with common method variance (CMV) as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2012). First, participants were assured that the answers would be processed anonymously. Second, by using established scales, we ensured that there was no ambiguity in the scale items. Third, we placed the constructs on the instrument in such a way that the predictor variable did not precede the criterion variable. Fourth, we conducted Harman’s single-factor analysis and found that the single factor extracted only 41% of the total variance, less than the 50% threshold value. Finally, we applied the marker variable assessment technique developed by Lindell and Whitney (2001). This method involved an additional latent variable (i.e., Goal advancement: 5 items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.70, CR = 0.71, AVE = 0.55) theoretically unrelated to the focal constructs. The smallest positive correlation of the marker with an observed variable (a proxy for the extent of the CMV) was 0.11. We then partialled out this effect from the raw correlation matrix using the Lindell-Whitney adjustment. Many of the originally significant correlations maintained their statistical significance post adjustment, suggesting that method bias did not pose a risk to our analysis.

Hypotheses Testing

As illustrated in Fig. 1, we had a mediated moderation model in which interactional justice moderates the relationship between ethical CSR and organizational identification, and organizational identification mediates the relationship between ethical CSR and job satisfaction. Following Muller et al. (2005) approach for testing mediated moderation, we estimated the two equations specified in the Appendix: (1) Model 1 comprised an assessment of the moderation of the effect of interactional justice on the mediator organizational identification; (2) Model 2 was an assessment of the moderation of the effect of the mediator organizational identification on job satisfaction, as well as the moderation of the residual treatment effect of interactional justice on job satisfaction.

We performed two bootstrapped mediated moderation analyses with 5,000 samples using Hayes’s (2013) PROCESS macro (Model 7). First, we found that organizational identity fully mediated the relationship between ethical CSR and job satisfaction (indirect effect b = 0.063, p < 0.05; direct effect b = 0.256, p < 0.01). H1 was supported given that ethical CSR is positively related to organizational identification (direct effect b = 0.331, p < 0.01). H2 was supported in that interactional justice positively moderates the effect of ethical CSR on organizational identification (b = 0.033, p < 0.05).

Our mediated moderation was supported because the indirect effect of the organizational justice x ethical CSR interaction on job satisfaction through organizational identity was significant (indirect effect b = 0.006, p < 0.05). Thus, our results also support H3: organizational identification mediates the interactive effects of ethical CSR and interactional justice on job satisfaction. The results also show that the conditional indirect effect of ethical CSR on job satisfaction was positive and significant at the high level of interactional justice (one standard deviation above the mean), the mean level of interactional justice, as well as at the low level of interactional justice (one standard deviation below the mean). Table 5 shows the regression results.

We also ran the base model without the interaction terms and found positive main effects for interactional justice, ethical CSR, and organizational identification (these models appear in Table 5), identical to the full model. Regarding the control variables, distributive justice and procedural justice had significant positive effects on organizational identification, and procedural justice was positively associated with job satisfaction.

Using Johnson–Neyman floodlight analysis technique (Spiller et al., 2013), we plotted interaction graphs (depicted in Fig. 2) for the first stage moderation effect of interactional justice on the relationship between ethical CSR and organizational identification. Figure 2 indicates that increasing interactional justice resulted in a significantly greater impact of ethical CSR on organizational identification. Further, the effect of ethical CSR on organizational identification was positive and significant at all levels of interactional justice.

We found that, as ethical CSR increases from the low level (one standard deviation below the mean) to the high level (one standard deviation above the mean), its total effect increased job satisfaction by 1.23. When interactional justice increased from its low level to its high level, its total effect increased job satisfaction by 0.69. In addition, although we used bootstrapping techniques to circumvent the power problem introduced by asymmetries and other forms of non-normality distribution often observed in small samples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008), our final small sample size might have affected the stability of the parameter estimates. However, following Aguinis and Gottfredson’s (2010) recommendations on statistical power analysis, we detected moderating effects that could not be artificial, thus our results did not suffer from low statistical power.

Robustness Checks

Additional analyses were performed to engender confidence in the validity of our results. The first follow-up analysis involved examining the predictive validity of Model 2 using the split-sample approach recommended by Armstrong (2001). As to the question of addressing unobserved heterogeneity in the hypothesized relationships, we randomly picked half of our sample as the estimation sample and the remaining half as the holdout sample. Using estimates from the estimation sample, we calculated the predicted value of organizational identification for each observation in the holdout sample. After computing the absolute deviation between the predicted value and the actual value, we calculated the absolute percentage error (the absolute deviation divided by the actual value) for each observation. These would indicate the extent to which the model predicted correctly. We found that, on average, the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) was 16%. This compared favorably with 31%, the MAPE that we would have obtained if the sample mean was used as the benchmark.

As our second check of the robustness of our findings, we have also reported results obtained without the two control variables (distributive justice and procedural justice). Extra controls can leverage correlations with other omitted variables, amplifying the potential for omitted variable bias (Clarke, 2005). We found that the estimated coefficients of the core variables were insensitive (both in terms of direction and significance levels) to our not including these control variables (see Table 6). In addition, we did not detect collinearity among the three facets of justice we assessed, confirming the stability of our results.

Discussion

Although scholarship at the intersection of business and society is in the ascendant, how an organization’s shared values, fairness, and ethical norms may de facto inform employee attitudes warrants more empirical scrutiny (Chatzopoulou, Manolopoulos, & Agapitou, 2021; De Cremer & Vandekerckhove, 2017). This research set out to theorize and furnish empirical evidence that organizational identification serves as a focal mechanism through which an interactive effect between ethical CSR and interactional justice strengthens job satisfaction.

Theoretical Implications

Our study makes three theoretical contributions to organizational studies. Foremost, as evidenced by the results, employees’ perceptions of their organization’s engagement in CSR activity can be an antecedent to their organizational identity. To this point, we contribute specifically to the micro-foundations of CSR—the ways in which individuals perceive and respond to the CSR-related initiatives of their organizations (Edinger-Schons et al., 2019; Gond et al., 2017).

Second, this study constitutes a rare attempt to empirically examine how ethical CSR and interactional justice might interact with respect to organizational identification, and thus informs future research at the intersection of CSR and organizational justice (e.g., De Roeck et al., 2014; Rupp et al., 2013). Our theoretical focus agrees with recent calls for a stronger theoretical foundation in this domain (van Dick et al., 2020). Our analyses reveal that a high degree of interactional justice increases organizational identity above and beyond the positive effect of ethical CSR. At a general level, our theory, supported by our results, suggests a greater interdependence between organizational justice and CSR (Rupp et al., 2015).

The third theoretical contribution lies in our mediation analysis demonstrating organizational identity as the key lynchpin and explaining the influence of the interaction of ethical CSR and interactional justice on job satisfaction. In tandem, not only does our conceptual framework help deepen the theoretical integration of social identity and social exchange perspectives (Chatzopoulou, Manolopoulos, & Agapitou, 2021), but it also comprises a response to the call for a “greater use of organizational identity in conjunction with other organizational studies constructs” (Whetten, 2006, p. 220). Placed in a broader conceptual perspective, this research brings to light novel insights into the intricacies of the organizational context underpinning the strategic alignment of organizational values and personal objectives (Slack et al., 2015).

Practice Implications

Our findings offer broad prescriptions aimed at the growing ranks of upper echelon managers overseeing organizational processes and managing employees. At a fundamental level, the data here reassert the indispensable role of corporate self-regulation and broad oversight in developing shared identities between organizations and their employees thereby also influencing employee-level outcomes. Consequently, we advocate that leaders hone their organizational sensibilities, beginning with a robust and clear commitment by the leadership ranks to incorporate into their practice a moral reference point, ethical guidelines, and good standards. Viewed in this light, managers would benefit from using a strategic dashboard to monitor employees’ perceptions regarding the firm’s stance concerning ethics and social values. In a larger context, firms can no longer straddle the fence when it comes to issues beyond their immediate domain—ethical and moral issues, such as income inequality, racial injustice, child labor, #MeToo, and DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion).

For companies that seek the maximal positive influence on organizational identity, our results offer a compelling recommendation. Our analyses strongly suggest that ethical CSR and interactional justice can work together as connected and reinforcing elements, and, when managed symbiotically, will reap greater rewards than when viewed in isolation. Beneath the surface, this hints at the possibility that, without strengthening the relational ties that employees have with their peers and supervisors, employees’ organizational identification would become impaired. We advise that firms consider developing leadership programs encouraging intermediary supervisors to build a trusting relationship with their team(s). From an operational standpoint, integrating ethical CSR into CSR-related communication with employees should be considered in light of these results.

Finally, to put our mediation analysis into perspective, organizations must go to greater lengths to stimulate a collective sense of identity among their employees. Organizational identity is a deep-lying construct in the minds of most employees, thus there would be value in monitoring it at the employee level and exercising discretion in the interpretation of any perceived fluctuations. We recommend that organizations set processes in place to shine a spotlight on employees’ CSR activities and achievements, both internally and externally. This is an important consideration, not least in terms of resonating with Olkkonen and Lipponen’s (2006) assertion that such organization-level procedures can facilitate a stronger employee-organization bond, but may also render organizational identity more salient by allowing employees’ views to feed into the firm’s design and practice of its CSR initiatives. Presumably, such actions will enhance employees’ perception of comfort for themselves and their peers thus avoiding dissonance and helping employees feel good about their job as well as their organizational membership. Given the centrality of employee job satisfaction, human resource managers have a good reason to pay attention to our findings.

Limitations and Future Research

This work has several limitations, which reflect opportunities for further research. First, being mindful of the cross-sectional nature of our data, any inferences regarding causal sequence can be best described as exploratory. Longitudinal design may prove useful to explore how relationships in our model unfold over a period of time. Although a potential drawback on its face, self-ratings were necessary as the focus was on employees’ perceptions. The moderation and mediated moderation that we found cannot be inflated by a CMV (Siemsen et al., 2010). We also exercised diligent care to mitigate the potential for CMV (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Second, although our analysis highlighted organizational identification as the intervening mediator, it cannot empirically rule out other conceivable mechanisms. It would be worthwhile to consider the prospect of other mediation sequences. Third, we can discern a limitation associated with the conceptualization of organizational identification. Employees can simultaneously identify with multiple groups and in-group and out-group identities could be different (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). A prime opportunity for future research involves disentangling these issues and recasting organizational identification as a multifaceted and nested construct. Finally, employees’ own sense of right or wrong as well as their self-perceived fit within the organizational ethicality could influence our relationships in ways that we did not study. Taking account of these issues will likely result in further refinements of our work on the interactions between CSR and justice. Relatedly, Slack et al. (2015) observe that all employees are not equally enchanted with various organizational activities.

Notes

Researchers have employed two other justice dimensions operationalized as employees’ perceptions of the fairness of the outcomes (i.e., distributive justice) and of the processes leading to said outcomes (i.e., procedural justice). Although not part of our conceptualization, these two dimensions of justice are included in our analysis.

References

Aguinis, H., & Gottfredson, R. K. (2010). Best-practice recommendations for estimating interaction effects using moderated multiple regression. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(6), 776–786.

Ahmad, S. (2018). Can ethical leadership inhibit workplace bullying across east and west: Exploring cross-cultural interactional justice as a mediating mechanism. European Management Journal, 36(2), 223–234.

Alegre, I., Mas-Machuca, M., & Berbegal-Mirabent, J. (2016). Antecedents of employee job satisfaction: Do they matter? Journal of Business Research, 69(4), 1390–1395.

Ambrose, M. L., Schminke, M., & Mayer, D. M. (2013). Trickle-down effects of supervisor perceptions of interactional justice: A moderated mediation approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(4), 678–689.

Armstrong, J. S. (2001). Evaluating forecasting methods. In J. S. Armstrong (Ed.), Principles of forecasting: A handbook for researchers and practitioners. Springer.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Au, A. K., & Leung, K. (2016). Differentiating the effect s of informational and interpersonal justice in co-worker interactions for task accomplishment. Applied Psychology, 65(1), 132–159.

Barnett, M. L., Henriques, I., & Husted, B. W. (2020). Beyond good intentions: Designing CSR initiatives for greater social impact. Journal of Management, 46(6), 937–964.

Bies, R. J. (2001). Interactional (in)justice: The sacred and the profane. In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 89–118). Stanford University Press.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. S. (1986). Interactional justice: communication criteria of fairness. In R. J. Lewicki, B. H. Sheppard, & M. H. Bazerman (Eds.), Research on negotiations in organizations (Vol. 1, pp. 43–55). JAI Press.

Bies, R. J., & Shapiro, D. L. (1987). Interactional fairness judgments: The influence of causal accounts. Social Justice Research, 1, 199–218.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

Brewer, M. B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this “we’’? Levels of collective identity and self-representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(1), 83–93.

Carroll, A. B. (2021). Corporate social responsibility: Perspectives on the CSR construct’s development and future. Business & Society, 60(6), 1258–1278.

Chatzopoulou, E.-C., Manolopoulos, D., & Agapitou, V. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: Interrelations of external and internal orientations with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Journal of Business Ethics, 179(3), 795–817.

Chiaburu, D. S. (2007). From interactional justice to citizen behaviors: Role enlargement or role discretion? Social Justice Research, 20(2), 207–227.

Clarke, K. A. (2005). The phantom menace: Omitted variable bias in econometric research. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 22(4), 341–352.

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations. A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Process, 86(2), 278–321.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425–445.

Cropanzano, R., Goldman, B., & Folger, R. (2003). Deontic justice: The role of moral principle in workplace fairness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(8), 1019–1024.

Cropanzano, R., Massoro, S., & Becker, W. J. (2017). Deontic justice and organizational neuroscience. Journal of Business Ethics, 144(4), 733–754.

Cropanzano, R., Prehar, C. A., & Chen, P. Y. (2002). Using social exchange theory to distinguish procedural from interactional justice. Group & Organization Management, 27(3), 324–351.

de Bakker, F. G. A., Matten, D., Spence, L. J., & Wickert, C. (2020). The elephant in the room: The nascent research agenda on corporations, social responsibility, and capitalism. Business & Society, 59(7), 1295–1302.

De Cremer, D., & Vandekerckhove, W. (2017). Managing unethical behavior in organizations: The need for a behavioral business ethics approach. Journal of Management & Operation, 22(3), 437–455.

De Roeck, K., El Akremi, A., & Swaen, V. (2016). Consistency matters! How and when does corporate social responsibility affect employees’ organizational identification? Journal of Management Studies, 53(1), 1141–1168.

De Roeck, K., Marique, G., Stinglhamber, F., & Swaen, V. (2014). Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: Mediating roles of overall justice and organisational identification. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(1), 91–112.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239–263.

Edinger-Scons, L. M., Lengler-Graif, L., Scheidler, S., & Wieseke, J. (2019). Frontline employees as corporate social responsibility ambassadors: A quasi-field experiment. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(3), 1–15.

Farooq, O., Rupp, D. E., & Farooq, M. (2017). The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Academy of Management Journal, 60(3), 954–985.

Folger, R. (2012). Deonance: Behavioral ethics and moral obligation. In D. De Cremer & A. E. Tenbrunsel (Eds.), Series in organization and management. Behavioral business ethics: Shaping an emerging field (pp. 123–142). Routledge.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Glavas, A., & Godwin, L. N. (2013). Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. Journal of Business Research, 114(1), 15–27.

Ghosh, K. (2018). How and when do employees identify with their organization? Perceived CSR, first-party (in)justice, and organizational (mis)trust at workplace. Personnel Review, 47(5), 1152–1171.

Gond, J., El Akremi, A., Swaen, V., & Babu, N. (2017). The psychological micro-foundations of corporate social responsibility: A person centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(2), 183–211.

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25(2), 161–178.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170.

Harrison, J. S., Phillips, R. A., & Freeman, R. E. (2020). On the 2019 business roundtable ‘statement on the purpose of a corporation.’ Journal of Management, 46(7), 1223–1237.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Jansen, P. (1982). Measuring homogeneity by means of Loevinger’s coefficient H: A critical discussion. Psychologische Beiträge, 24, 96–105.

Joo, Y. R., Moon, H. K., & Choi, B. K. (2016). A moderated mediation model of CSR and organizational attractiveness among job applicants: Roles of perceived overall justice and attributed motives. Management Decision, 54(6), 1269–1293.

Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five-factor model of personability and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(3), 530–541.

Jung, H.-J., & Ali, M. (2017). Corporate social responsibility, organizational justice and positive employee attitudes: In the context of Korean employment relations. Sustainability, 9(11), 1992.

Kim, J., Millman, J. F., & Lucas, A. F. (2021). Effects of CSR on affective organizational commitment via organizational justice and organization-based self-esteem. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102691.

Lee, E. S., Park, T. Y., & Koo, B. (2015). Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 1049–1080.

Lichtenstein, D. R., Drumwright, M. E., & Braig, B. M. (2004). The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported nonprofits. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 16–32.

Lind, E. A. (2001). Fairness heuristic theory: Justice judgments as pivotal cognitions in organizational relations. In J. Greenberg & R. Cropanzano (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 56–88). Stanford University Press.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121.

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1349). Rand McNally.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103–123.

Muller, D., Judd, C. M., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(6), 852–863.

Murshed, F., Sen, S., Savitskie, K., & Xu, H. (2012). CSR and job satisfaction: Role of CSR importance to employee and procedural justice. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 29(4), 518–533.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2011). Mplus user’s guide. Muthén & Muthén.

O’Reilly, J., Aquino, K., & Skarlicki, D. (2016). The lives of others: Third parties’ responses to others’ injustice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(2), 171–189.

Olkkonen, M. E., & Lipponen, J. (2006). Relationships between organizational justice, identification with the organization and the work-unit, and group-related outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100(2), 202–215.

Patient, D. L., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2010). Increasing interpersonal and informational justice when communicating negative news: The role of the manager’s emphatic concern and moral development. Journal of Management, 36(2), 55–78.

Peterson, D. K. (2004). The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Business & Society, 43(3), 296–319.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendation on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(5), 879–903.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). The big idea: Creating shared value. How to reinvent capitalism- and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harvard Business Review, 89(1–2), 62–77.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Rupp, D. E., Ganapathi, J., Aguilera, R. V., & William, C. A. (2006). Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(4), 537–543.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personal Psychology, 66(4), 895–933.

Rupp, D. E., Wright, P. M., Aryee, S., & Luo, Y. (2015). Organizational justice, behavioral ethics, and corporate social responsibility: Finally the three shall merge. Management and Organization Review, 11(1), 15–24.

Schwartz, M. S., & Carroll, A. B. (2003). Corporate social responsibility: A three-domain approach. Business Ethics Quarterly, 13(4), 503–530.

Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 456–476.

Slack, R. E., Corlett, S., & Morris, R. (2015). Exploring employee engagement with (corporate) social responsibility: A social exchange perspective on organizational participation. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(3), 537–548.

Spiller, S. A., Fitzsimons, G. J., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & McClelland, G. H. (2013). Spotlights, floodlights, and magic number zero, Simple effects tests in moderated regression. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(2), 277–288.

Starbucks, (2022). Retrieved from https://starbucks.com/about-us/company-information.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of inter-group relations. Brooks/Cole.

Tax, S. S., Brown, S. W., & Chandrashekaran, M. (1998). Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: Implications for relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 60–76.

Thornton, M. A., & Rupp, D. E. (2016). The joint effect of justice climate, group moral identity, and corporate social responsibility on the prosocial and deviant behaviors of groups. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(4), 677–697.

Tziner, A., Oren, L., Bar, Y., & Kadosh, G. (2011). Corporate social responsibility, organizational justice and job satisfaction: How do they interrelate, if at all? Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 27(1), 67–72.

van Dick, R., Crawshaw, J. R., Karpf, S., Schuh, S. C., & Zhang, X. (2020). Identity, importance, and their roles in how corporate social responsibility affects workplace attitudes and behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(2), 159–169.

van Dick, R., van Knippenberg, D., Kerschreiter, R., Hertel, G., & Wieseke, J. (2008). Interactive effects of work group and organizational identification on job satisfaction and extra-role behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72(3), 388–399.

van Knippenberg, D., & Sleebos, E. (2006). Organizational identification versus organizational commitment: Self-definition, social exchange, and job attitudes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(5), 571–584.

Vendenberg, R. J., & Lance, Ch. E. (1992). Examining the causal order of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Journal of Management, 18(1), 153–167.

Vogel, D. J. (2005). Is there a market for virtue? The business case for corporate social responsibility. California Management Review, 47(4), 19–45.

Whetten, D. A. (2006). Albert and Whetten revisited: Strengthening the concept of organizational identity. Journal of Management Inquiry, 15(3), 219–274.

Yakovleva, N., & Vazquez-Brust, D. (2012). Stakeholder perspective on CSR of mining in Argentina. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(2), 191–211.

Zheng, L. (2020). We’re entering the age of corporate social justice. In Harvard Business Review, June 15, 2020.

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank Herman Aguinis, Frederik Beuk, Joan Carlini, Lawrence Feick, Ravi Madhavan, Neil Morgan, Corinne Post, John Prescott, and Niels van de Ven for their insightful comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that they have no potential conflict of interest.

Human or Animals Rights

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standard of institutional research committee.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The two equations estimated:

-

(1)

The moderation of the effect of interactional justice on the mediator organizational identity:

-

(2)

The moderation of the effect of the mediator organizational identification and the moderation of the residual treatment effect of interactional justice on job satisfaction:

$$\begin{aligned} {\text{Job}}\_{\text{satisfaction}}_{i} = & \, \theta_{0} + \theta_{1} {\text{Interactional}}\_{\text{justice}}_{i} + \theta_{2} {\text{Ethical}}\_{\text{CSR}}_{i} \\ & + \;\theta_{3} {\text{Interactional}}\_{\text{justice}}*{\text{Ethical}}\_{\text{CSR}}_{i} + \theta_{4} {\text{Org}}\_{\text{identification}} \\ & + \;\theta_{5} {\text{Org}}\_{\text{identification}}*{\text{Ethical}}\_{\text{CSR}} + \theta_{6} {\text{Distributive}}\_{\text{justice}}_{i} \\ & + \;\theta_{7} {\text{Procedural}}\_{\text{justice}}_{i} + \theta_{8} {\text{Gender}}_{i} + \theta_{9} {\text{Age}}_{i} + \theta_{10} {\text{Firm}}\_{\text{age}}_{i} \\ & + \;\theta_{11} {\text{Work}}\_{\text{tenure}}_{i} + \;\theta_{12} {\text{Position}}\_{\text{tenure}}_{i} + \theta_{13} {\text{Employees}}_{i} \\ & + \;\theta_{14} {\text{Education}}_{i} + + \theta_{15} {\text{Firm}}\_{\text{revenue}}_{i} + \theta_{16} {\text{Job}}\;{\text{title}}_{i} + \lambda_{i} \\ \end{aligned}$$where i refers to the individual, εi, ξi and λi are the error term. The remaining independent variables were described in the previous subsection.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Murshed, F., Cao, Z., Savitskie, K. et al. Ethical CSR, Organizational Identification, and Job Satisfaction: Mediated Moderated Role of Interactional Justice. Soc Just Res 36, 75–102 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-022-00403-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-022-00403-5