Abstract

Purpose

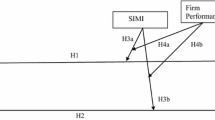

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of a pro-environmental corporate message on prospective applicants’ attitudes toward a fictitious hiring organization. Drawing from signaling theory, we hypothesized that an environmental message on the organization’s recruitment website would increase prospective applicants’ perceptions of organizational prestige, which would then increase job pursuit intentions. Personal environmental attitudes were also examined as a possible moderator.

Design/Methodology/Approach

Participants (N = 183) viewed a web site printout that either did or did not contain a message indicating the organization’s environmental support. Participants rated their attitudes toward the environment, perceptions of the organization, and job pursuit intentions.

Findings

Findings demonstrated that the environmental support message positively affected job pursuit intentions; further, this effect was mediated by perceptions of the organization’s reputation. Contrary to the person–organization fit perspective, the message’s effects on job pursuit intentions were not contingent upon the participant’s own environmental stance.

Implications

These findings highlight the importance of corporate social performance as a source of information for a variety of job seekers. Even relatively small amounts of information regarding corporate social performance can positively affect an organization’s reputation and recruitment efforts.

Originality/Value

In general, this research contributes to the growing body of literature on corporate social responsibility. It is the first study to test whether the effects of pro-environmental recruiting messages on job pursuit intentions depend upon an applicant’s personal environmental stance. In addition, this is the first study to demonstrate reputation’s meditational role in the effects of corporate social responsibility on recruitment efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the years, recruitment research has focused on the characteristics of traditional sources of recruitment information (e.g., newspaper advertisements and recruiters) to identify variables that affect prospective employees’ impressions of recruitment materials, their reactions to organizations, and their willingness to pursue employment with a hiring organization. Today, the Internet provides a common medium for relaying information to potential applicants, yet little is known about the manner in which company web sites influence prospective employees. Compared with job advertisements and even recruitment brochures, web sites often give companies more advertising space, particularly because layers or levels of information can be offered to job seekers who want detail on a particular topic of interest. When creating their organizational web sites, companies must give serious consideration to how they want to portray themselves. Lately, it has become increasingly common for organizations to incorporate messages concerning their company values. For instance, organizations may communicate values such as diversity, the environment, or work–life balance.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the effects of a pro-environmental message embedded in the recruitment section of an organizational web site. We examined whether such a message increases the willingness of an individual to pursue employment with a hiring organization. Drawing from a person–organization (P–O) fit perspective, we then investigated whether prospective applicants’ personal attitudes toward the environment moderated this effect. Lastly, we tested a mediator suggested by signaling theory. In particular, we examined whether views of the prospective employer’s reputation underlie the effects of a pro-environment message on job pursuit intentions.

Corporate Social Performance

Closely tied to an organization’s image and reputation is its corporate social performance. Corporate social performance is a construct that addresses an organization’s responsibilities to multiple stakeholders, including its employees and the greater community. This type of performance is in addition to an organization’s responsibilities to its economic stakeholders (Clarkson 1995; Donaldson and Preston 1995; Turban and Greening 1997). A company’s social policies and programs reflect its social performance and can include policies pertaining to community relations, treatment of women and minorities, employee relations, and treatment of the environment. The social performance of a company can influence prospective applicants’ perceptions of an organization’s image and their initial attraction to that organization by denoting certain values and norms (Fombrun and Shanley 1990; Greening and Turban 2000; Rynes 1991). Additionally, perceptions of corporate social responsibility have been shown to relate to workers’ organizational commitment (Brammer et al. 2007).

During recent years, it has become commonplace for large organizations to relay information concerning their social performance (Aiman-Smith et al. 2001; Poe and Courter 1995). Companies such as IBM, General Motors, and Microsoft include information in their recruitment materials that emphasizes their philanthropic and environmental initiatives. This information can be communicated via the Internet. For example, by browsing the corporate web sites of Fortune 500 organizations such as GM, Coca-Cola, Dupont, and Lucent, one can obtain clear statements about their environmental policies with links to reports on their environmental activity (Aiman-Smith et al. 2001). With the growth of Internet recruiting, company web sites are an important medium for advertising environmental support and other social performance efforts to customers, investors, and prospective employees.

Research has demonstrated the significant effects of an organization’s corporate social performance on applicant attraction. Turban and Greening (1997) found that companies with higher corporate social performance ratings had more positive reputations. They examined corporate social performance as a multidimensional construct. Corporate social performance dimensions and their relationships to organizational reputation included: community relations (r = .16), employee relations (r = .20), environment (r = .20), product quality (r = .21), and treatment of women and minorities (r = .15). Treatment of women and minorities was the only corporate social performance variable that was not significantly related to reputation. Companies with higher corporate social performance ratings were also more attractive for employers than those with lower ratings. Community relations, employee relations, and product quality were significantly related to attractiveness with correlations ranging from .16 to .25. Similarly, Brammer and Pavelin (2006) found in a survey of large global firms that social performance was one of the several factors that determined the firm’s reputation. Based on these findings, it seems clear that an organization’s positive corporate social performance can provide a competitive advantage in attracting applicants.

A study by Aiman-Smith et al. (2001) compared two types of corporate social performance, ecological ratings and lay-off policy, along with pay and promotional opportunity in order to determine their relative importance in predicting attractiveness. The strongest predictor of organizational attractiveness was ecological rating (β = .34, p < .001), thus indicating that an organization’s ecological practices play a major role in how attractive applicants deem the organization. Ecological rating was also a significant predictor of job pursuit intentions (β = .19, p < .001). This finding was supported by past research that has shown that an organization’s stance on the environment affects applicants’ job pursuit intentions (Bauer and Aiman-Smith 1996). In general, corporate social performance appears to be a valuable predictor of initial recruiting outcomes, but deserves further examination in order to explain the underlying mechanisms of these relationships.

P–O Fit: Personal Environmental Stance as a Moderator

One might reason that prospective applicants who personally value the environment will be particularly influenced by a pro-environment message posted by a hiring organization. This rationale is consistent with the person–organization (P–O) fit perspective, which suggests that individuals will be most attracted to organizations that have cultures congruent with their own set of values. Prospective applicants interpret the characteristics of the organization in light of their own needs and values, thus applicants’ perceived fit is a result of their appraisal of the interaction between their personal values and needs and the characteristics of the organization (Chapman et al. 2005; Kristof 1996).

Prior research has provided support for the link between P–O fit and recruiting outcomes. A meta-analysis by Chapman et al. (2005) found P–O fit to be a significant predictor of job pursuit intentions (ρ = .62). This relationship outweighed a number of other predictors including organization and recruiter characteristics. In addition to job pursuit intentions, P–O fit was correlated with organization attraction (r = .40). Similar findings were reported in a meta-analysis by Kristof-Brown et al. (2005), who found a correlation of .46 between P–O fit and organizational attraction. Although informative, these meta-analytic findings do not address the reasons why P–O fit affects recruiting outcomes.

In an effort to further understand the influence of P–O fit on organizational recruitment, research regarding consumer preferences can be explored. Such work has examined whether the success of environmental advertising is dependent on a consumer’s personal environmental values. A study by Follows and Jobber (2000) did not support the proposition that environmental value congruence between an individual and an organization advertising a product necessarily increases the probability that the individual will engage in environmentally responsible purchasing behavior. In this case, the individual consequences of purchasing a product, such as convenience, limited availability, and product quality, outweighed the positive environmental consequences. Even if an individual valued the environment, the individual consequences decreased the probability of environmentally responsible purchasing behavior (β = −0.63, p < .05).

Moving beyond consumer research, studies in the employment domain have looked at prospective applicants’ attitudes toward the environment. Bauer and Aiman-Smith (1996) examined job seekers’ personal environmental attitudes as well as the effect of a pro-environment message on the willingness to pursue employment with an organization. Participants in this study were randomly assigned to view the brochure of an environmentally friendly or neutral organization. It was hypothesized that the participant’s personal environmental stance would increase their attraction to the organization, their intentions to pursue employment, and their willingness to accept a job offer from the hiring organization. The findings indicated that job applicants were more likely to pursue employment (β = .26, p < .001) and accept job offers (β = .31, p < .001) from pro-environment organizations. However, the study did not explore a potential P–O fit interaction. Rather, the researchers’ focus was first to investigate whether a pro-environment message attracted prospective applicants regardless of their personal environmental stance, and second to investigate if a pro-environmental personal stance would increase overall attraction to an organization. It is of interest to examine these variables in a different manner, by testing whether the effects of pro-environmental recruiting messages on job pursuit intentions are contingent upon an applicant’s personal environmental stance.

In short, although the literature has laid a foundation for our first hypothesis, no prior research has looked at whether a job seeker’s personal environmental stance moderates the effect that a company’s pro-environmental web site may have on job pursuit intentions.

Hypothesis 1

An organization’s pro-environment message will affect the job pursuit intentions of prospective employees who are relatively supportive of the environment more than it affects the preferences of those who are relatively unsupportive of the environment.

Signaling Theory: Organizational Reputation as a Mediator

In addition to understanding which types of people are most likely to be influenced by environmental messages, it is also important to consider the mechanisms underlying the effect of pro-environment messages on prospective applicants. Although the reasons for the linkage between organizational concern for the environment and applicant attraction remain untested, the literature offers some insights concerning the psychological processes mediating this effect. Signaling theory provides a basis for understanding the phenomenon. Because selection procedures are a critical source of information for applicants, the image created by a selection procedure is believed to affect an organization’s ability to attract candidates (Mecan et al. 1994; Richman-Hirsch et al. 2000; Smither et al. 1993). Signaling theory applies this logic to the recruitment domain. It asserts that job seekers form perceptions of prospective employers based on incomplete information they encounter during the job search process, such as recruiters and recruitment brochures (Rynes and Miller 1983). In effect, people sense that recruiters and other information gleaned during the job search process provide a signal of what it would be like to work for the organization under consideration. The signaling process is most likely to occur when applicants must make employment decisions based on little information about hiring organizations (Rynes et al. 1991), which is frequently the case when people are searching for jobs online. According to Turban and Greening (1997), “an organization’s social policies and programs may attract potential applicants by serving as a signal of working conditions in the organization” (p. 659). In essence, an employee may form the belief that because an organization cares for the environment, it will care for its employees as well.

A prospective employer’s reputation also appears to be involved in this process. Several authors have suggested that a company’s willingness to support the environment influences job seekers’ perceptions of the organization’s reputation (Brammer and Millington 2005; Lewis 2003; Turban and Greening 1997). Reputation, in turn, signals important job attributes (Cable and Turban 2003).

Reputation can also affect the pride that individuals expect from organizational membership. Social identity theory states that individuals seek to identify themselves through the groups in which they can claim membership (Tajfel and Turner 1986). An individual working for an organization perceived as prestigious can expect to feel personal pride as a result. With regard to environmental issues, workers can point to their organization’s environmental policies as evidence that they are also environmentally responsible. Therefore, job seekers’ perceptions of an organization’s prestige and social responsibility can influence their job pursuit intentions (Cable and Turban 2003).

In summary, the results of past research collectively suggest the following mediated model, which awaits empirical investigation.

Hypothesis 2

Perceptions of an organization’s reputation will mediate the effect of a pro-environment message on prospective applicants’ job pursuit intentions.

Method

Participants

A total of 264 individuals participated in the study. Participants who identified themselves as freshmen were eliminated from the final sample, based on the assumption that freshmen were unlikely to be entering the job market in the near future. This left 183 eligible participants. The sample was comprised of 36.6% sophomores, 32.2% juniors, 30.1% seniors, and 1.1% graduate students. Approximately 58.5% of the participants were female, and the mean age was 21.1 (SD = 2.56). The ethnicity of the sample was as follows: 59.6% Caucasian; 26.2% African American; 6.6% Asian; 4.4% Hispanic; 0.5% American Indian; 2.2% Mixed with parents from two different groups; and 0.5% who self-identified as “Other.”

Participants were identified by undergraduate and graduate research assistants attending two large public universities in the southeastern United States. The research assistants were given the opportunity to identify individuals interested in participating (e.g., friends, classmates, and research volunteers fulfilling course research requirements). The research assistants administered the study materials in person at various locations, based on room availability and participant locale.

Design and Procedure

Participants were asked to imagine themselves as active job seekers while completing a task that required them to review a printout of a fictitious organizational web site, “RLA, Inc.” Next, the participants answered survey questions about themselves and rated their attitudes concerning employment with the organization featured on the web site printout. Measured variables included: participants’ attitudes toward the environment, perceptions of the organization’s reputation, job pursuit intentions, and perceptions of the organization’s support toward the environment.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions corresponding to two different versions of the fabricated web site printout. The content and format of these single-page printouts were adapted from existing employment web sites and created for the purpose of this study. One printout included a pro-environment message in the form of a recycling symbol (see Fig. 1), whereas the second printout did not contain the symbol (see Fig. 2). The pro-environment web site also prominently featured the statement, “RLA Supports the Environment,” along with a link which presumably led to additional information about RLA’s environmental programs. Both printouts alluded to a host of openings for management positions at the fictitious organization. With the exception of the experimental manipulation described above, the two web sites contained identical layouts and text.

Measures

Two questionnaires were presented after participants had the opportunity to review the web site printout. The participant questionnaire was administered first and included demographic measures and items assessing participants’ personal attitudes toward the environment. These were questions from Dunlap and Van Liere (1978) New Environmental Paradigm (NEP) Scale, published in 1978 and revised by Dunlap et al. (2000). This 15-item measure (alpha = .76) used a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale to assess respondents’ views of items such as “When humans interfere with nature it often produces disastrous consequences.” Half of the items were negatively worded and reverse scored after data entry. Higher scores reflected more favorable attitudes toward the environment.

The organizational questionnaire was developed by Highhouse et al. (2003). This measure used a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale to assess both job pursuit intentions (5 items, alpha = .81) and participants’ views of the organization’s prestige (5 items, alpha = .76). Responses to each subscale were averaged; therefore, both job pursuit intentions and prestige could range between 1 and 5, with higher scores representing higher levels of the constructs under investigation. A sample job pursuit question includes: “I would make RLA, Inc. one of my first choices as an employer.” Example prestige items are “Employees are probably proud to say they work at RLA, Inc.,” “This is a reputable company to work for,” and “RLA, Inc. probably has a reputation as being an excellent employer.” Although the authors of these items labeled this an “organizational prestige” scale, the items appear to assess what is commonly viewed as “reputation” in the literature pertaining to the present study. We therefore used Highhouse et al.’s (2003) prestige scale to operationalize reputation.

Finally, four items (alpha = .83) were included as a manipulation check. These items asked participants to use a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale to rate their agreement with statements such as “Valuing the environment is a top priority of RLA, Inc.” Responses to the four items were averaged; therefore, perceptions of RLA, Inc.’s environmental stance could range between 1 and 5, where high scores represented assured beliefs that RLA, Inc. was indeed dedicated to supporting the environment. Statistical analysis confirmed that the manipulation was successful (see Table 1).

Results

The means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for all study variables are presented in Table 2. Hypothesis 1 stated that personal environmental stance would moderate the relationship between the pro-environmental message and the prospective employee’s job pursuit intentions. To test this hypothesis, linear regression was used. All variables of interest were first centered, which reduced the multicollinearity problem that is often encountered when entering an interaction term into a regression analysis (Aiken and West 1991). The results from the moderation analysis are presented in Table 3.

As shown in Tables 1 and 3, the main effect of the pro-environmental message was significant, such that participants who saw the pro-environmental message were especially inclined to indicate willingness to pursue employment with the company. However, neither the main effect of personal environmental stance was significant, nor was the interaction between personal environmental stance and the pro-environmental message (see Table 3). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was not supported.

Hypothesis 2 stated that the effect of the pro-environmental message would be mediated by perceptions of the organization’s reputation. Following the method presented by Baron and Kenny (1986), a set of linear regression equations was used to determine whether (a) the independent variable (message) is related to the outcome (job pursuit), (b) the mediator (reputation) is related to the outcome variable (job pursuit), and (c), the independent variable (message) is related to the mediator (reputation). Finally, for mediation to be established, the effect of the independent variable should be reduced or eliminated when the mediator is introduced into the regression equation. The result of this set of analyses supports a mediated model. First, the pro-environmental message was found to predict job pursuit intentions (B = .18, p = .02). Second, the pro-environmental message was found to predict perceptions of the organization’s reputation (B = .16, p = .03). Finally, when both reputation and the pro-environmental message were considered simultaneously, reputation was found to predict job pursuit intentions (B = .61, p < .001), while the effect of the pro-environmental message was reduced to a nonsignificant level (B = .08, p = .19). These findings support Hypothesis 2.

Discussion

The findings of the present study provide insights into the manner in which organizational web sites influence prospective applicants’ job pursuit attitudes. Overall, an environmental message posted on a recruitment web site increased job pursuit intentions. However, contrary to our first hypothesis, the effect of the environmental message on job pursuit intentions was not moderated by the applicant’s personal environmental stance. This is consistent with recent research regarding consumer preferences, which has demonstrated that the success of environmental advertising is not solely dependent on the consumer’s personal environmental values (Follows and Jobber 2000). The person–organization fit model does not appear to explain the effects of environmental advertising on job seekers. The decision to pursue employment with an environmentally responsible company may instead be influenced by the tradeoff between multiple factors, such as pay, benefits, and the negative consequences of working for a non-environmentally responsible company.

Our second hypothesis, regarding the mediational role of an organization’s reputation, was supported. The analysis demonstrates that an environmental message on a company’s web site has the effect of improving the perceived reputation of the company, and in turn the enhanced reputation of a company makes it more attractive to prospective employees. The implications of this finding are noteworthy. The identification of reputation as a mediating factor indicates that a company’s reputation plays a role in determining the effect of a pro-environmental stance. The underlying reasons for this, however, are still unclear. One possible explanation for this relationship is that job-seekers associate pro-environmental activities with successful and lucrative companies. In essence, individuals may believe that if an organization can spend money on the environment then it is reputable, prestigious, stable, and can afford to pay its employees well. A second possible reason for the mediational role of reputation is that job-seekers may view an organization’s concern for the environment as a sign that it is respectable, caring, trustworthy, and will therefore show concern not just for the environment but its employees. This rationale is consistent with signaling theory, which proposes that prospective employees interpret information gained during the recruitment process as a sign of how they will be treated by the hiring organization. Thus, an organization’s reputation regarding the environment may be an indication of how well it cares for its employees.

Limitations and Future Research

It is important to view these results in the context of several limitations. First, the experimental stimulus used was not an actual web site, but a printout of a web site. A web site is a dynamic, interactive medium, while the printout provided no opportunity for interaction. This was an important aspect of our study design because it allowed us to standardize and control the information the participants received. However, it may have limited the external validity of the findings.

Reliance on data from a student sample also raises external validity concerns. However, it should be noted that many large organizations invest heavily in recruitment on college campuses (Rynes and Boudreau 1986). Moreover, numerous organizational positions are filled using college recruitment tactics, such as web sites targeted to younger adults, or the placement of a recruiter on campus (Rynes and Boudreau 1986). This suggests that the sample was representative of individuals for whom organizations spend significant resources trying to recruit. In addition, the recent meta-analysis by Chapman et al. (2005) confirmed that laboratory-based research can play a vital role in recruiting research. They found that the relationship between individuals’ perceptions of organizational characteristics and their job pursuit intentions did not vary based on whether the sample consisted of real applicants versus non-applicants. The effect sizes reported in lab studies were not significantly different from those found in field studies.

Lastly, it should be noted that the effect of the pro-environment message was relatively small in this study, increasing willingness to pursue employment by only .26 on a five-point scale. As such, the size of the effect of the pro-environment message (β = .17, p < .05) was somewhat weaker than the previous findings of Bauer and Aiman-Smith (1996) (β = .26, p < .001). Nevertheless, the statistical significance of these findings should not be ignored; instead researchers and practitioners should hold realistic expectations about the amount of influence pro-environmental messages can have on job pursuit intentions. Perhaps more effort, beyond a simple statement on a web site, should be invested by an organization in order to see larger effects. For example, an organization could provide additional detail to the applicant about their investment in the environment, such as partnerships with environmental organizations or employee testimonials about their involvement with pro-environment initiatives.

The preceding limitations notwithstanding, the present study contributes to the growing research on employee recruiting in several ways. First, we formally examined and failed to find support for the assertion that an individual’s personal environmental stance moderates the effect of a pro-environmental web site on job pursuit intentions. While implied in the literature (e.g., Bauer and Aiman-Smith 1996), this relationship remained untested prior to the present study. Secondly, we examined and found support for the role an organization’s reputation plays when prospective applicants see a pro-environmental recruitment message on an organization’s web site. This finding provides valuable information regarding the decision process that takes place when an individual considers pursuing a job.

Future research might expand upon the present findings by investigating precisely why a pro-environmental message enhances the perceived reputation of an organization. Specifically, what attributions does a job-seeker make when s/he sees such a message? Both signaling theory and social identity theory have been proposed as possible vehicles for these attributions. Social identity theory suggests that a job-seeker would expect to experience an enhanced self-concept from being employed by a reputable, environmentally conscious organization. Meanwhile, signaling theory purports that the company’s reputation provides an indication of how much it would care about its employees. Another explanation from signaling theory is that organizational support for the environment may shape applicant assumptions about the stability of the organization and its financial generosity toward employees. It is necessary to examine which, if any, of these factors contribute to the findings uncovered in this study.

Future research should also investigate the possibility of a P–O fit interaction. Although an interaction was not found in this study, there may be contextual factors that masked the true effect. For example, some other features of the web site may have influenced prestige perceptions in addition to the environmental message.

Another avenue for research is to investigate whether an organization’s environmental stance affects more distal outcomes, beyond job pursuit intentions (e.g., accepting a job offer, job satisfaction, and/or retention). Longitudinal studies, following individuals from the job-seeking stage to actual employment and retention, would be informative. Lastly, future research should examine if the findings from the present study can generalize to other corporate social performance variables. For example, does community involvement enhance an organization’s reputation in the same manner as environmental awareness? Other social performance variables to consider are the treatment of women and minorities and employee relations.

Practical Implications

The findings of this study may be of value to organizations wishing to improve recruiting initiatives. Companies can begin by advertising their environmental efforts in order to attract more applicants. If an organization is not currently proactive toward environmental issues, it might consider the benefits of becoming involved and publicizing their activities. Organizations that already support the environment should be advised that providing information about their ecological initiatives can be a low-cost practical recruitment mechanism. A primary medium for communicating this type of information is in the recruitment portion of an organization’s web site. This placement will ensure that applicants do not overlook ecological information and that they incorporate it into their decision-making process. Finally, advertising environmental support may be effective even in the absence of extensive details regarding the organization’s environmental track record. The findings from the present study suggest that even a small amount of information about an organization’s environmental efforts can have a significant effect on whether an individual wishes to pursue a job.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. California: Sage Publications.

Aiman-Smith, L., Bauer, T. N., & Cable, D. M. (2001). Are you attracted? Do you intend to pursue? A recruiting policy-capturing study. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16(2), 219–237. doi:10.1023/A:1011157116322.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bauer, T. N., & Aiman-Smith, L. (1996). Green career choices: The influence of ecological stance on recruiting. Journal of Business and Psychology, 10, 445–458. doi:10.1007/BF02251780.

Brammer, S. J., & Millington, A. (2005). Corporate reputation and philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 61, 29–39. doi:10.1007/s10551-005-7443-4.

Brammer, S. J., Millington, S., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18, 1701–1719.

Brammer, S. J., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of fit. Journal of Management Studies, 43, 435–455. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00597.x.

Cable, D. M., & Turban, D. B. (2003). The value of organizational reputation in the recruitment context: A brand-equity perspective. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 2244–2266. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01883.x.

Chapman, D. S., Uggerslev, K. L., Carroll, S. A., Piasentin, K. A., & Jones, D. A. (2005). Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 928–944. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.928.

Clarkson, M. B. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20, 92–117. doi:10.2307/258888.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20, 65–91. doi:10.2307/258887.

Dunlap, R. E., & Van Liere, K. D. (1978). The ‘new environmental paradigm’. The Journal of Environmental Education, 9, 10–19.

Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. D., Mertig, A. G., & Emmet-Jones, R. (2000). Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. The Journal of Social Issues, 56, 425–442. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00176.

Follows, S. B., & Jobber, D. (2000). Environmentally responsible purchase behaviour: A test of a consumer model. European Journal of Marketing, 34(5), 723–746. doi:10.1108/03090560010322009.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 233–258. doi:10.2307/256324.

Greening, D. W., & Turban, D. B. (2000). Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Business & Society, 39, 254–268. doi:10.1177/000765030003900302.

Highhouse, S., Lievens, F., & Sinar, E. (2003). Measuring attraction to organizations. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63, 986–1001. doi:10.1177/0013164403258403.

Kristof, A. L. (1996). Person–organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualization, measurement, and implications. Personnel Psychology, 49, 1–50. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01790.x.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. Z. (2005). Consequences of individual’s fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x.

Lewis, S. (2003). Reputation and corporate responsibility. Journal of Communication Management, 7, 356–364. doi:10.1108/13632540310807494.

Mecan, T. H., Avedon, M. J., Paese, M., & Smith, D. E. (1994). The effects of applicants’ reactions to cognitive ability tests and an assessment center. Personnel Psychology, 47, 715–735. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1994.tb01573.x.

Poe, R., & Courter, C. L. (1995). Ethics anyone? Across the Board, 32(2), 5–6.

Richman-Hirsch, W. L., Olson-Buchanan, J. B., & Drasgow, F. (2000). Examining the impact of administration medium on examinee perceptions and attitudes. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 880–887. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.880.

Rynes, S. L. (1991). Recruitment, job choice, and post-hire consequences: A call for new research directions. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 399–444). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Rynes, S. L., & Boudreau, J. W. (1986). College recruiting in large organizations: Practice, evaluation, and research implications. Personnel Psychology, 29, 729–759. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1986.tb00592.x.

Rynes, S. L., Bretz, R. D., Jr, & Gerhart, B. (1991). The importance of recruitment in job choice: A different way of looking. Personnel Psychology, 44, 487–521.

Rynes, S. L., & Miller, H. E. (1983). Recruiter and job influences on candidates for employment. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 147–154. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.68.1.147.

Smither, J. W., Reilly, R. R., Millsap, R. E., Pearlman, K., & Stoffey, R. W. (1993). Applicant reactions to selection procedures. Personnel Psychology, 46, 49–76.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 658–672. doi:10.2307/257057.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on this manuscript. We also thank Tracey Gabelman, Kelly Taylor and the East Carolina University students who assisted with data collection and idea generation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Received and reviewed by former editor, George Neuman.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Behrend, T.S., Baker, B.A. & Thompson, L.F. Effects of Pro-Environmental Recruiting Messages: The Role of Organizational Reputation. J Bus Psychol 24, 341–350 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9112-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9112-6