Abstract

For emerging adults, the development of psychosocial intimacy may be a key developmental task shaped by past parenting. In this study, 232 emerging adult, college students completed a questionnaire about their intimacy development, identity development, self-efficacy in romantic relationships, parenting (i.e., attachment styles, parental caring and overprotection, and parental challenge), and well-being (i.e, depressive symptoms, loneliness, happiness, and self-esteem). Findings indicate that identity development, low attachment avoidance, and self-efficacy in romantic relationships predicted intimacy development. Furthermore, those individuals with high intimacy have less loneliness, greater self-esteem, and more happiness than those with low intimacy. Achieving psychosocial intimacy may have benefits for well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Psychosocial intimacy for emerging adults may be a key developmental task (Havighurst 1972). In Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development, one must reconcile innate drives and the expectations from society to surmount developmental crises or turning points at age-graded times of development. At each stage of development, there may be a central “crisis” or task that prompts resolution and successful progression onto the next phase of life. For young adults, Erik Erikson (1968) focused on establishment of psychosocial intimacy as the central task, which he described as forming a romantic relationship and developing more mature ways of relating, including mutuality and a secure sense of one’s self in the relationship. Across his writings, though, Erikson indicated that psychosocial intimacy extends beyond physical and sexual relationships with peers. He noted that “sexual intimacy is only part of what I have in mind, for it is obvious that sexual intimacies do not always wait for the ability to develop a true and mutual psychological intimacy with another person” (Erikson 1980, p. 101). Erikson’s notion of psychosocial intimacy applied to deeper and more intimate relationships with peers, not just sexual ones, and has remained as a central developmental task for young adulthood (Marcia and Josselson 2013). However, less is understood of what may contribute to how individuals develop psychosocial intimacy.

Erikson noted that the precursor to developing real intimacy was the development of an identity. He asserted that once the identity is formed, one can fuse that identity with that of another to develop a sense of intimacy. Later research had also substantiated the importance of forming an identity for the development of intimacy (Moore and Bolero 1991; Whitbourne and Tesch 1985). Beyers and Seiffge-Krenke (2010) found support that there was a “clear developmental ordering” to identity and intimacy in support of Erikson’s theory (p. 405). Montgomery (2005) found that identity development was an independent contributor from other variables to predicting intimacy development in emerging adults. Given that identity continues to develop into at least emerging adulthood (Schwartz 2007) and, perhaps beyond, psychosocial intimacy is likely supported by identity development or may be an important milestone towards identity consolidation in emerging adulthood.

Although Eriksonian theory focuses on individual development, the basic tenets for the theory include the contexts in which development is taking place. For much of childhood and into adolescence, the family is a central contextual influence on development. Furthermore, given his epigenetic principle, the outcomes of previous stages can be re-experienced in the context of the current stage for individuals. It then stands to reason that, during emerging adulthood and the psychosocial tasks of that stage, that the development of psychosocial intimacy may be reflective of the parenting and parent-child relationship one experienced in the past. Most notably, Johnson and Galambos (2014) found in their longitudinal study that parent-adolescent relationship quality was a significant predictor of young adult intimate relationship quality, ten and 15 years later. Similarly, Rollins et al. (2017) found that family cohesion in adolescence was related to marital satisfaction in adulthood and less cohabitation in adulthood. However, what remains elusive are which aspects of parenting and parent-child relations may relate to psychosocial intimacy.

One fundamental component of parent-child relations may be the early attachment that is formed. Erikson’s psychosocial theory of development and John Bowlby’s theory of attachment have common origins in psychoanalytic theory. Bowlby’s and Erikson’s theoretical tenets parallel and complement one another throughout childhood and at least into emerging adulthood and form the basis from which relationships may be understood (Pittman et al. 2011). Nowadays, attachment theory has emerged as a central theory in understanding adult romantic relationships (Simonelli et al. 2004). According to attachment theory, parents and their child form a reciprocal bond and the amount of attunement and responsiveness of the parents to the child’s needs shapes his or her understanding of interpersonal relationships. This understanding becomes an “internal working model” from which a child will perceive later relationships with close others and, later as an adolescent and emerging adult, with romantic partners as well. This pattern of relating has been interpreted as an attachment style along two dimensions of attachment anxiety and attachment avoidance (Sanford 1997). Individuals with high anxiety are overly concerned with the relationship, for example, and those with high avoidance do not desire close, intimate relationships. The attachment pattern becomes the outcome of the parent-child relationship as manifest in later intimate relationships.

Research has indicated that the attachment pattern may apply to a romantic partner in adolescence and emerging adulthood, where psychosocial intimacy may be enacted (Bartholomew and Horowitz 1991). Adult attachment research has found that attachment avoidance in romantic relationships has been associated being uncomfortable with intimacy (Fraley et al. 1998), with using sex to avoid closeness and control the relationship (Birnbaum 2007), and with using drugs or alcohol prior to sex (Tracy et al. 2003). Attachment anxiety has been associated with unsafe sexual practices in order to achieve intimacy (Schachner and Shaver 2004), requiring more time, affection, and self-disclosure to feel close in a relationship (Hudson and Fraley 2017), and more relationship-disclosure conversation in a laboratory situation (Tan et al. 2012). Since parents contribute to the development of the attachment style, which later may influence attachment in intimate relationships, it is worthwhile to investigate how the attachment style may influence one’s development of psychosocial intimacy. Given that the construct behind attachment style is about comfort and concern about close relationships, attachment may undergird the achievement of intimacy.

The attachment pattern established in infancy and applied to intimate relationships in adolescence and emerging adulthood form one aspect of how parent-child relationships may affect psychosocial intimacy. Parenting may also contribute to one’s development of psychosocial intimacy. Parenting can be broadly understood as the approach of guidance, discipline, and interactions parent undertake with their children.

Parenting in the parenting style model is comprised of warmth and caring dimensions and of control and autonomy-granting dimensions (Maccoby and Martin 1983). The warmth dimension is about how much caring, compassion, and communication there is from the parent (Openshaw et al. 1984). In contrast, the control dimension comprises how much concern for rules, regulation of behavior, and demands for compliance. In general, optimal parenting results from high levels of warmth and of control that are developmentally appropriate (Darling and Steinberg 1993). For emerging adults, the parenting may shift where an adaptive response may be less parental control and maintenance of warmth and engagement (Nelson et al. 2011).

Parenting contributes to the psychological and relational tools for emerging adults to develop intimacy. For example, McKinney et al. (2016) found that emerging adults who indicated effective parenting reported higher psychological adjustment with low levels of externalizing and internalizing problems. Rodriguez et al. (2016) indicated that emerging adults’ emotional regulation ability was explained by history of parenting style as reported by parents and the emerging adults. They further described that emotional regulation from authoritative parenting predicted better mental health outcomes and lower delinquent behaviors. For emerging adults, supportive parenting may also have been protective of engaging in risky sexual behavior and promotive of commitment in romantic relationships (Simons et al. 2013). In addition, respondents in that study who reported supportive parenting indicated sensitivity and similarity of values as desired attributes of a romantic partner above physical attractiveness, which, in turn, predicted less risky sexual behavior. Moreover, perceived parental acceptance among college students was protective of engaging in high risk behaviors, particularly casual sex and oral sex (Schwartz et al. 2009). For men, fathering behavior predicted the quality of romantic relationships (Karre 2015). When reporting their findings that nurturant-involved parenting in adolescence predicted the quality of romantic relationships in emerging adults, Donnellan et al. (2005) noted “that individuals partially develop their approach to relating to romantic partners through the parent-child socialization process” (p. 573). Given the findings across studies, it is likely that parenting practices may be promotive of the development of psychosocial intimacy.

Intimacy development may relate to overall well-being in emerging adulthood. Developing more intimate relationships with others may be a key developmental process for emerging adults (Arnett 2000; Shulman and Connolly 2013), which, if not achieved, may have deleterious outcomes. In one study, poor psychosocial intimacy development in 16 to 22 year olds, particularly for girls and women, was associated with Cluster B symptoms (i.e., borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders) from the DSM-IV (Crawford et al. 2004). In contrast, the development of psychosocial intimacy in the college years predicted midlife satisfaction (Sneed et al. 2012). In addition, intimacy development in emerging adulthood predicted greater marital adjustment 25 years later (Boden et al. 2010). Resolution of intimacy may be central for emerging adults and may allow them to move towards forming more stable romantic relationships in adulthood.

In Arnett’s conceptualization of emerging adulthood, explorations in love in emerging adulthood are noted as “more intimate and serious” in contrast to those in adolescence (Arnett 2000, p. 473). He further explained that emerging adulthood is the time where young people have opportunity to explore romantic and sexual relationships, given diminished parental supervision and the distance from committed, enduring relationships. Erikson’s notions of psychosocial intimacy—where one engages in intimate, romantic, and sexual relationships--are consistent with Arnett’s description of emerging adulthood. Moreover, Shulman and Connolly (2013) noted that “it is reasonable to assume that emerging adults have already developed the necessary competencies to establish intimate relationship of long duration” (p. 29). The skills for psychosocial intimacy may be developed in adolescence and practiced and implemented during emerging adulthood. Given the greater acceptance of premarital sex, increased non-marital cohabitation, and later ages of marriage and parenthood (Arnett 2007), it is likely that emerging adulthood affords unique opportunities for the advancement of psychosocial intimacy.

Individuals’ sense of self-efficacy in romantic relationships may be an indicator of their readiness for psychosocial intimacy. Self-efficacy is the belief that one can control actions or circumstances to achieve an outcome, and, in romantic relationships, it may be how one thinks about managing romantic relationships (Bandura 1997). When it comes to romantic relationships, self-efficacy has been positively associated with ability to solve conflict with the relationship partner (Cui et al. 2008), increased level of commitment to and satisfaction with the romantic relationship (Lopez et al. 2007), and increased social support from a romantic partner (Girme et al. 2015). Self-efficacy in romantic relationships may be indicative of how individuals negotiate relationships and later satisfaction (Weiser and Weigel 2016), two concepts reflected in the achievement of psychosocial intimacy.

Given the scant research on psychosocial intimacy, we are adding to the understanding of how individuals’ sense of intimacy is developed. First, we explore demographic differences among the variables. Second, we hypothesize that identity development, attachment style, parenting and self-efficacy in romantic relationships will predict intimacy development. Third, we hypothesize that those who have high intimacy will have fewer depressive symptoms, less loneliness, greater self-esteem, and more happiness than those with low intimacy.

Method

Participants

For this study, 232 undergraduate students (Female = 180, Male = 50), aged 18 to 25 (M = 21.64 years, SD = 1.72), completed an online questionnaire about their parental relationships, attachment style, measures of well-being, and identity and intimacy development. The ethnic composition for the sample was 2.6% African American, 7.8% Asian American, 34.5% White, 42.2% Latino, .4% Native American, and 12.5% Mixed or Multiracial. Given the small representation in some ethnic categories, the groups other than White or Latino were collapsed into an Other category (23.3%) for analyses.

Procedure

Undergraduate students from the campus psychology research participant pool and from other upper-division General Education classes at a suburban, West coast university completed an online questionnaire for research participation or extra credit in their classes. Once consent was granted, participants completed the questionnaire in about 30 to 45 min. The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects approved this protocol.

Measures

Demographics

Participants indicated their age, ethnicity, major, gender, and current type of residence.

Identity

Participants completed the Identity subscale from Erikson Psychosocial State Inventory (EPSI) (Rosenthal et al. 1981). Participants rated 12 items, such as “I’ve got a clear idea of what I want to be,” using the scale of 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .87.

Intimacy

We used the Intimacy subscale from Rosenthal et al. (1981) Erikson psychosocial state inventory (EPSI). In this measure, participants rated, using the scale of 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, 12 items, such as “I’m ready to get involved romantically with a special person.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .82.

Attachment orientation

Participants rated the nine items of the Experiences in Close Relationships-Relationships Structures Questionnaire (ECR-RS; Fraley et al. 2011), using a scale of 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The items were modified to use “parent” rather than specifying the participant-designated parent. The measure yields two subscales of attachment anxiety (three items) and attachment avoidance (six items). Sample items include “I’m afraid that this parents may abandon me” (anxiety) and “It helps to turn to this parent in times of need” (reverse-scored; avoidance). Cronbach’s alphas for the entire measure and the subscales, respectively are .70, .83, and .91.

Parental Bonding Instrument

Participants indicated their views of parental care and parental overprotection by rating 25 items of the Parental Bonding Instrument, using the scale 1 = very unlike my parent to 4 = very like my parent (Parker et al. 1979). The measure produces two subscales: parental caring and parental overprotection. An example item is “My parent spoke to me in a warm and friendly voice” (caring) and “My parent let me do things I liked doing” (reverse-scored; overprotection), respectively. Cronbach’s alphas for the two subscales were .92 and .82, respectively.

Parental Challenge Questionnaire

We used Dailey’s (2008) 10-item measure of parental challenge to assess how much parents provided a nurturant and stimulating environment for the emerging adults. Participants rated ten items, using the scale 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. A sample item is “My parent helped me channel my negative emotions into more positive actions.” Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .93.

Self-efficacy in Romantic Relationships

Participants completed, the Self-efficacy in Romantic Relationships Scale, a 12-item measure to assess self-efficacy in romantic relationships, using a scale of 1 = strongly disagree to 9 = strongly agree (Riggio et al. 2011). A sample item is “I am just one of those people who is not good at being a romantic relationship partner.” Cronbach’s alpha was .91.

We are measuring well-being across four dimensions: depressive symptoms, loneliness, happiness, and self-esteem.

Depressive Symptoms

Participants indicated how often in the last week they experienced depressive symptoms as described in the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff 1977), using a scale of 1 = rarely or none of the time to 4 = most or all of the time. A sample item is “This week, I have been bothered by things that usually don’t bother me.” Cronbach’s alpha was .80.

Loneliness

We used the UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3) to assess participant’s reported loneliness (Russell 1996). Participants indicated how often they experience aspects of loneliness, using a scale of 1 = never to 4 = often. A sample item is “How often do you feel that you ‘in tune’ with the people around you.” Cronbach’s alpha was .91

Happiness

To assess happiness, we used Lyubomirsky and Lepper’s (1999) measure of subjective happiness. Participants rated four items to indicate their happiness. A sample item includes “In general, I consider myself,” rated with 1 = not a very happy person to 7 = a very happy person. Cronbach’s alpha was .85.

Self-esteem

We used Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale Rosenberg (1989) to measure self-esteem. On the scale, participants indicated their agreement with ten statements on a Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). An example of an item is “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.” Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

Data Analyses

In order to assess demographic differences among the variables, we used Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to investigate differences by gender and by ethnicity, respectively, and used Pearson’s product-moment correlation to assess associations with age. To investigate which variables predicted psychosocial intimacy, we conducted a hierarchical linear regression. To determine how psychosocial well-being and psychosocial intimacy were related, we looked at associations among the variables using Pearson’s product-moment correlations. Then, we used Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) to compare participants who were low in intimacy and high in intimacy on measures of well-being.

Results

We first assessed whether there were demographic differences among the variables of interest. There were two gender differences. Women were significantly higher on parental overprotection (M = 27.78, SD = 7.53) and depressive symptoms (M = 8.82, SD = .66) than men (M = 24.98, SD = 6.53; M = 7.10, SD = .99), F(1, 231) = 3.97, p < .05 and F(1, 231) = 9.83, p < .01, respectively. There were several significant ethnic differences on avoidant attachment, parental caring, parental overprotection, parental challenge, intimacy, depression, and loneliness. See Table 1 for details. There were no significant associations between age and any of the variables of interest.

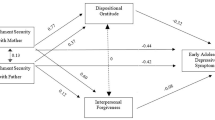

In order to predict if identity development, attachment style, parenting and self-efficacy in romantic relationships relate to intimacy development, we conducted a hierarchical linear regression. Because there were ethnic differences on intimacy, ethnicity was entered in the first step. Identity development was entered next in the next block, given that identity and intimacy have been associated in past research and may account for a portion of the variance. Next, the attachment measures, parenting measures and the self-efficacy in romantic relationships measure were entered together. The final model was significant, R2 = .06, ΔR2 = .35 for Step 2, and ΔR2 = .20 for Step 3 (ps < .001 for Step 2 and Step 3). Further analyses of the variables indicate that identity, self-efficacy in romantic relationships, and lack of avoidant attachment to parents were the significant predictors of intimacy. Hypothesis 2 was partially supported. See Table 2 for detail.

We first conducted correlations among the variables of interest to identify the associations among the variables of interest (See Table 3). As expected, intimacy was positively associated with parental caring, parental challenge, self-efficacy in romantic relationships, happiness, and self-esteem. Intimacy was negatively associated with attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, parental overprotection, depressive symptoms, and loneliness.

In order to investigate if well-being related to intimacy, we divided scores on intimacy by the mean to create high and low intimacy groups. We then conducted a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with depressive symptoms, loneliness, self-esteem, and happiness as dependent variables, controlling for gender and ethnicity. Using Pillai’s trace, there was a significant effect of intimacy on well-being, V = .39, F(4, 227) = 36.92, p < .001. See Table 4. However, separate ANOVAs on the outcomes revealed a trend rather than statistical significance on depressive symptoms, F(1, 230) = 3.46, p = .06. Hypothesis 3 was primarily supported.

Discussion

Achievement of psychosocial intimacy is a central developmental task for emerging adults. Psychosocial intimacy involves deeper, intimate relationships with peers, which may include physical intimacy with romantic partners as well as emotional intimacy with romantic partners and peers. Although Erikson asserted that identity development must be resolved in order to successfully achieve intimacy, recent research has indicated that emerging adults may continue to consolidate their identities and, especially, through romantic relationships and the intimate relationships with peers (Michałek 2016). One’s ability to achieve intimacy, though, may be shaped by one’s experience with parenting, particularly attachment. Given that parents, generally, model partner relationships and shape the parent-child relationship, it is likely that emerging adults’ perceptions of their parenting may relate to their achievement of intimacy. In addition, achieving intimacy, especially during emerging adulthood, may be associated with well-being. With the centrality of social and romantic relationships in emerging adulthood, those individuals who are able to achieve intimacy may derive personal enhancement and avoid negative psychological outcomes.

In this study, we found that identity achievement, a lack of avoidant attachment, and self-efficacy in romantic relationships predicted intimacy. Identity predicting intimacy is consistent with past literature and Erikson’s theory that identity must be achieved prior to intimacy development. Low levels of avoidant attachment to parents contributing to intimacy is also consistent with the tenets of Attachment theory, which indicate that low avoidant attachment means that one is comfortable with close, intimate relationships. The contribution of self-efficacy in romantic relationship may be tapping into an aspect of readiness for or maturity in preparing for intimate relationships (Riggio et al. 2013). Moreover, this finding may indicate that comfort with close relationships stemming from the parent-child relationship, comfort with intimate romantic relationships, and having a sense of one’s identity are together supportive of the achievement of the developmental task of psychosocial intimacy.

Those individuals with low intimacy were higher on loneliness, lower on self-esteem, and lower on happiness than those with high intimacy. Those low on intimacy were also somewhat higher on depressive symptoms (p < .10). These findings support the hypothesis and are consistent with the research that intimacy achievement is an important developmental milestone for youth to achieve (See, for example, Johnson et al. 2012). When youth do not establish intimate relationships, there may be some deleterious outcomes.

Limitations

Despite these findings, there are a few limitations that should be considered. The sample size is relatively small and skews towards women, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the larger population. In addition, the initial ethnic differences may belie a cultural component to how past parenting and intimacy are related that are not addressed in this study. There is also no measure of current relationship status, and it could be that those who have achieved intimacy are successfully in a romantic relationship. Further, being in a romantic relationship may make one feel more self-efficacious in navigating romantic relationships, which may bias how respondents perceived the items in the measure. The study design is also cross-sectional, which limits the directionality of the findings. With a longitudinal study, there may be opportunities to ascertain if parenting influences are more prominent and if self-efficacy in romantic relationships, in particular, change over time.

Despite these limitations, this study provides some key findings. Psychosocial intimacy is associated with identity, past parenting (i.e, attachment style, parental caring and overprotection, and parental challenge), and well-being (i.e., depressive symptoms, loneliness, happiness, and self-esteem). Psychosocial intimacy may be associated with comfort with close relationships as learned through parental attachment bonds, individual identity development, and personal confidence and comfort with romantic relationships. Achieving psychosocial intimacy may ameliorate feelings of loneliness and support happiness and self-esteem, which is consistent with the notion that romantic relationships may be a developmental task for emerging adults.

References

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: What is it, and what is it good for? Child Development Perspectives, 1, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00016.x.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226.

Beyers, W., & Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2010). Does identity precede intimacy? testing Erikson’s theory on romantic development in emerging adults of the 21st century. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25, 387–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558410361370.

Birnbaum, G. E. (2007). Attachment orientations, sexual functioning, and relationship satisfaction in a community sample of women. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24, 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507072576.

Boden, J. S., Fischer, J. L., & Niehuis, S. (2010). Predicting marital adjustment from young adults’ initial levels and changes in emotional intimacy over time: A 25-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adult Development, 17, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9078-7.

Crawford, T. N., Cohen, P., Johnson, J. G., Sneed, J. R., & Brook, J. S. (2004). The course and psychosocial correlates of personality disorder symptoms in adolescence: Erikson’s developmental theory revisited. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 373–387. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOYO.0000037631.87018.9d.

Cui, M., Fincham, F. D., & Pasley, B. K. (2008). Young adult romantic relationships: The role of parents’ marital problems and relationship efficacy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1226–1235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208319693.

Dailey, R. M. (2008). Parental challenge: Developing and validating a measure of how parents challenge their adolescents. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25, 643–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407508093784.

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487.

Donnellan, M. B., Larsen-Rife, D., & Conger, R. D. (2005). Personality, family history, and competence in early adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 562–576. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.562.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1980). Identity and the life cycle. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Fraley, R. C., Davis, K. E., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Dismissing-avoidance and the defensive organization of emotion, cognition, and behavior. In J. A. Simpson, W. S. Rholes, J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 249–279). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Fraley, R. C., Heffernan, M. E., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2011). The experiences in close relationships—Relationship Structures Questionnaire: A method for assessing attachment orientations across relationships. Psychological Assessment, 23, 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022898.

Girme, Y. U., Overall, N. C., Simpson, J. A., & Fletcher, G. O. (2015). ‘All or nothing’: Attachment avoidance and the curvilinear effects of partner support. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 450–475. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038866.

Havighurst, R. J. (1972). Developmental tasks and education. Edinburgh, UK: Longman.

Hudson, N. W., & Fraley, R. C. (2017). Adult attachment and perceptions of closeness. Personal Relationships, 24, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12166.

Johnson, M. D., & Galambos, N. L. (2014). Paths to intimate relationship quality from parent–adolescent relations and mental health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(1), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12074.

Johnson, H. D., Kent, A., & Yale, E. (2012). Examination of identity and romantic relationship intimacy associations with well-being in emerging adulthood. Identity: An International Journal of Theory And Research, 12, 296–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2012.716381.

Karre, J. K. (2015). Fathering behavior and emerging adult romantic relationship quality: Individual and constellations of behavior. Journal of Adult Development, 22, 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-015-9208-3.

Lopez, F. G., Morúa, W., & Rice, K. G. (2007). Factor structure, stability, and predictive validity of college students’ relationship self-efficacy beliefs. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 40, 80–96.

Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46, 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006824100041.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. In Mussen, P. H.(Series Ed.), Hetherington, E. M. (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Socialization, personality, and social development Vol. 4 (pp. 1–101). New York, NY: Wiley.

Marcia, J., & Josselson, R. (2013). Eriksonian personality research and its implications for psychotherapy. Journal of Personality, 81, 617–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12014.

McKinney, C., Morse, M., & Pastuszak, J. (2016). Effective and ineffective parenting: Associations with psychological adjustment in emerging adults. Journal of Family Issues, 37, 1203–1225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X14537480.

Michałek, J. (2016). Relations with parents and identity statuses in the relational domain in emerging adults. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 4, 146–154. https://doi.org/10.5114/cipp.2016.61757.

Montgomery, M. J. (2005). Psychosocial intimacy and identity: From early adolescence to emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20, 346–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558404273118.

Moore, S., & Bolero, J. (1991). Psychosocial development and friendship functions in adolescence. Sex Roles, 25, 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00290061.

Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L., Christensen, K. J., Evans, C. A., & Carroll, J. S. (2011). Parenting in emerging adulthood: An examination of parenting clusters and correlates. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 730–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9584-8.

Openshaw, D. K., Thomas, D. L., & Rollins, B. C. (1984). Parental influences of adolescent self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence, 4, 259–274.

Parker, G., Tupling, H., & Brown, L. B. (1979). A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02487.x.

Pittman, J. F., Keiley, M. K., Kerpelman, J. L., & Vaughn, B. E. (2011). Attachment, identity, and intimacy: Parallels between bowlby’s and erikson’s paradigms. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 3, 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00079.x.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306.

Riggio, H. R., Weiser, D. A., Valenzuela, A. M., Lui, P. P., Montes, R., & Heuer, J. (2013). Self-efficacy in romantic relationships: Prediction of relationship attitudes and outcomes. The Journal of Social Psychology, 153, 629–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2013.801826.

Riggio, H. R., Weiser, D., Valenzuela, A., Lui, P., Montes, R., & Heuer, J. (2011). Initial validation of a measure of self-efficacy in romantic relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 601–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.026.

Rodriguez, C. M., Tucker, M. C., & Palmer, K. (2016). Emotion regulation in relation to emerging adults’ mental health and delinquency: A multi-informant approach. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1916–1925. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0349-6.

Rollins, P., Williams, A., & Sims, P. (2017). Family dynamics: Family-of-origin cohesion during adolescence and adult romantic relationships. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-017-9430-1.

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 20–40. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2.

Rosenberg, M. (1989). Society and the Adolescent Self-Image. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Rosenthal, D. A., Gurney, R. M., & Moore, S. M. (1981). From trust to intimacy: A new inventory for examining Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10, 525–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02087944.

Sanford, K. (1997). Two dimensions of adult attachment: Further validation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 14, 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407597141008.

Schachner, D. A., & Shaver, P. R. (2004). Attachment dimensions and sexual motives. Personal Relationships, 11, 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00077.x.

Schwartz, S. J. (2007). The structure of identity consolidation: Multiple correlated constructs of one superordinate construct? Identity: An International Journal of Theory And Research, 7, 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283480701319583.

Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert, R. D., Kim, S. Y., Weisskirch, R. S., Williams, M. K., & Finley, G. E. (2009). Perceived parental relationships and health-risk behaviors in college-attending emerging adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 727–740. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00629.x.

Shulman, S., & Connolly, J. (2013). The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood: Reconceptualization of the field. Emerging Adulthood, 1, 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696812467330.

Simonelli, L. E., Ray, W. J., & Pincus, A. L. (2004). Attachment models and their relationships with anxiety, worry, and depression. Counseling and Clinical Psychology Journal, 1, 107–118.

Simons, L. G., Burt, C. H., & Tambling, R. B. (2013). Identifying mediators of the influence of family factors on risky sexual behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22, 460–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9598-9.

Sneed, J. R., Whitbourne, S. K., Schwartz, S. J., & Huang, S. (2012). The relationship between identity, intimacy, and midlife well-being: Findings from the Rochester Adult Longitudinal Study. Psychology and Aging, 27, 318–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026378.

Tan, R., Overall, N. C., & Taylor, J. K. (2012). Let’s talk about us: Attachment, relationship‐focused disclosure, and relationship quality. Personal Relationships, 19, 521–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01383.x.

Tracy, J. L., Shaver, P. R., Albino, A. W., & Cooper, M. L. (2003). Attachment styles and adolescent sexuality. In P. Florsheim & P. Florsheim (Eds.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 137–159). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Weiser, D. A., & Weigel, D. J. (2016). Self-efficacy in romantic relationships: Direct and indirect effects on relationship maintenance and satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 152–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.013.

Whitbourne, S. K., & Tesch, S. A. (1985). A comparison of identity and intimacy statuses in college students and alumni. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1039–1044. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1039.

Author Contributions

R.S.W. designed and executed the study, completed the data analyses, and wrote the manuscript and its revisions.

Funding

This study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Robert S. Weisskirch declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at California State University, Monterey Bay approved the protocol of this study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weisskirch, R.S. Psychosocial Intimacy, Relationships with Parents, and Well-being among Emerging Adults. J Child Fam Stud 27, 3497–3505 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1171-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1171-8