Abstract

The changing nature of the transition to adulthood in western societies, such as the United States, may be extending the length of time parents are engaged in “parenting” activities. However, little is known about different approaches parents take in their interactions with their emerging-adult children. Hence, this study attempted to identify different clusters of parents based on the extent to which they exhibited both extremes of control (psychological control, punishment, verbal hostility, indulgence) and responsiveness (knowledge, warmth, induction, autonomy granting), and to examine how combinations of parenting were related to emerging adult children’s relational and individual outcomes (e.g. parent–child relationship quality, drinking, self-worth, depression). The data were collected from 403 emerging adults (M age = 19.89, SD = 1.78, range = 18–26, 62% female) and at least one of their parents (287 fathers and 317 mothers). Eighty-four percent of participants reported being European American, 6% Asian American, 4% African American, 3% Latino, and 4% reported being of other ethnicities. Data were analyzed using hierarchical cluster analysis, separately for mothers and fathers, and identified three similar clusters of parents which we labeled as uninvolved (low on all aspects of parenting), controlling-indulgent (high on both extremes of control and low on all aspects of responsiveness), and authoritative (high on responsiveness and low on control). A fourth cluster was identified for both mothers and fathers and was labeled as inconsistent for mothers (mothers were above the mean on both extremes of control and on responsiveness) and average for fathers (fathers were at the mean on all eight aspects of parenting). The discussion focuses on how each of these clusters effectively distinguished between child outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The changing nature of the transition to adulthood in western societies, such as the United States, may be extending the length of time parents are engaged in “parenting” activities. For example, the majority of 18–29 year olds (i.e., emerging adults) do not consider themselves to be adults (e.g., Arnett 2000), nor do their parents (Nelson et al. 2007). Therefore, many parents feel they still need to help their children navigate this period of experimentation and exploration, while at the same time allowing them the independence they want and need. Indeed, as emerging adults strive to gain more autonomy by fulfilling adult roles (Aquilino 1996, 2006; Schnaiberg and Goldenberg 1989), the parent–child dyad enters a new stage of commonality where different styles of interaction and mutuality may emerge (Aquilino 1997, 2006). As such, parenting may look different in emerging adulthood than in childhood or adolescence, but it may still play an important role. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine a variety of dimensions of parenting used by parents of emerging adult children, and to explore how parenting is related to child outcomes.

Parenting During Childhood and Adolescence

Warmth/responsiveness and control have been identified as central features that tend to distinguish mothers and fathers in their approaches to parenting (e.g., Baumrind 1967, 1978; Maccoby and Martin 1983; Roberts 1986). It has been shown that warm, supportive parenting involves behaviors that are physically and emotionally affectionate, approving, loving, and caring (Openshaw et al. 1984), while control includes the demands or expectations that parents place upon their children and the degree of monitoring present in parenting. Much of the parenting literature has focused on parenting styles (i.e., authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, and uninvolved) which differ along these dimensions of warmth/responsiveness and control/demandingness. For example, authoritative parents tend to display warmth towards and hold high expectations for their children. Expectations are clearly communicated, rules are firm and rational, and discipline is administered in a consistent manner (Baumrind and Black 1967). Authoritarian parents are characterized by low levels of warmth and high levels of control. This parenting style allows for strong parental command over the child, and minimal input from the child in decisions, or in expressions of views or opinions (Baumrind 1991). Permissive parenting is characterized as exhibiting high levels of warmth (displayed through overindulgence) and low levels of control. Permissive parents tend to be non-demanding (do not expect maturity and responsibility) and avoid controlling/correcting behavior or the outlining of boundaries in the children’s environment (Baumrind 1991; Baumrind and Black 1967). Finally, uninvolved or neglectful parents tend to exhibit low levels of both warmth and control (Steinberg et al. 2006). Taken together, the dimensions of warmth/responsiveness and control have provided the foundation for mapping out various approaches to parenting in childhood and adolescence. However, much less is known regarding the role of these dimensions in emerging adulthood.

Parenting During Emerging Adulthood

There is a fair amount of work that has been done with college students examining the parent–child relationship, attachment, and broader parenting-related variables such as living arrangements (at home vs. dorm vs. apartment), and economic support (see Aquilino 2006 for a review). For example, Barry et al. (2008) demonstrated that a positive mother–child relationship was linked to emerging adults’ regulation of values and prosocial tendencies. From an adult-attachment perspective, securely attached emerging adults have been found to have greater self worth (Kenny and Sirin 2006) and greater perceived personal efficacy (Leondari and Kiosseoglou 2002). There is also some work identifying aspects of emerging adulthood that are associated with changes in the parent–child relationship, such as the impact of moving away from home (e.g., Buhl 2007).

Thus, while the work in these areas (e.g., parent–child relationship, adult attachment) is growing, the specific work on parenting dimensions or styles is much more limited. Much of the work that has been done has focused on the link between early parenting (i.e., in childhood and adolescence) and subsequent outcomes in emerging adulthood. For example, retrospective accounts of parenting during adolescence and outcomes for emerging adults have shown, not surprisingly, that emerging adult children tended to exhibit more positive functioning when they experienced positive parenting in childhood and adolescence (e.g., Berzonsky 2004; Smits et al. 2008). Longitudinal work shows similar findings. For example, being reared by authoritative parents is associated with positive outcomes for emerging adults, including areas of competence and resilience (Masten et al. 2004) and self-esteem and self-actualization (Buri et al. 1988; Dominguez and Carton 1997). Furthermore, levels of involvement, warmth, support, and acceptance in earlier years influenced emerging adults’ individuation, psychological adjustment, and healthy relationships (Tubman and Lerner 1994) while a lack thereof has been linked to less affection, greater depression, and more relationship strain in emerging adulthood (Gomez and McLaren 2006; Whitbeck et al. 1994).

While this research makes significant contributions to understanding associations between early parenting and subsequent child outcomes, retrospective and longitudinal studies do not help us understand how current parenting in emerging adulthood may be linked to children’s behaviors, nor what that parenting might look like. Indeed, there is a dearth of work examining various specific dimensions of parenting, including warmth/responsiveness and control, during emerging adulthood. Somewhat related, there is a growing body of work that has examined the relation between young people’s perceptions of their mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles (authoritative, authoritarian, permissive) and child outcomes such as emotional adjustment (McKinney and Renk 2008a, b), academic performance (e.g., Turner et al. 2009), adjustment to university life (e.g., Wintre and Yaffe 2000), and drinking behaviors (e.g., Patock-Peckham and Morgan-Lopez 2009).

However, the work examining parenting styles in emerging adulthood seems somewhat premature, as there is little evidence indicating that parenting looks the same in emerging adulthood as it did earlier in the lifespan. Indeed, the scales that were employed in the majority of these studies (e.g., Parental Authority Questionnaire—PAQ; Buri, 1991) were originally designed for adolescents or for emerging adults to provide a retrospective assessment of what their parents did while the children were growing up. Therefore, there is little evidence to suggest that the PAQ or similar measures tap dimensions of parenting that are relevant in emerging adulthood. Taken together, there are still several limitations to the work that has been done examining parenting in emerging adulthood, including that the extant work is retrospective, is focused on how earlier parenting (childhood or adolescence) impacts emerging adults, includes only child perspective (i.e., no parent report), focuses only on mothers, and/or uses measures that have been designed for the study of parenting styles in adolescence.

Current Study

Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine various dimensions of parenting and how they might combine or cluster to help us understand the potentially different approaches to parenting taken by mothers and fathers of emerging adult children. Specifically, in order to examine the potentially different approaches to and dimensions of parenting used by mothers and fathers of emerging adult children, the current study attempted to identify different clusters of parents based on the extent to which they exhibited the dimensions of warmth/responsiveness and control, both of which have been considered central in distinguishing different types of parenting during childhood and adolescence (Hart et al. 2003). In order to tap aspects of control, we chose to examine three ways in which control might be exhibited by parents of emerging adults: including psychologically (i.e., psychological control such as withdrawing love when child does not do what the parent wants), behaviorally (i.e., punishment, such as withholding some form of financial support), and verbally (i.e., verbal hostility such as yelling or shouting disapproval of a child’s actions) as well as the absence of control (i.e., indulgence such as giving into a child to avoid a confrontation). To get at warmth/responsiveness, we chose to explore three aspects of parenting that have been found to reflect a responsive, child-centered approach to parenting (Hart et al. 2003) including warmth (i.e., responding to a child’s feelings or needs), induction (reasoning with a child), and autonomy granting (showing respect for a child’s opinions and decisions) as well as parental knowledge which is believed to reflect appropriate parental involvement in emerging adulthood (Padilla-Walker et al. 2008). Given the exploratory nature of these cluster analyses, and the lack of relevant extant literature, no specific hypothesis were made.

The second purpose of the study was to see if the clusters that emerged would be related differentially to aspects of adaptive and maladaptive characteristics of emerging-adult children. An extensive literature on parenting in childhood and adolescence has found that child outcomes vary based on the extent to which parents exhibit warmth and control. For example, parenting that reflects warmth and appropriate control has been linked to numerous positive outcomes including independence, creativity, persistence, leadership skills, self-control, high self-esteem, self-reliance, respect for parents, prosocial behavior, and high academic performance; while parenting that is high in control but low in warmth/responsiveness is linked to children’s low self-esteem, low sociability, moodiness, apprehensiveness, stress, delinquency, and substance abuse (see Hart et al. 2003 for a review). Taken together, there is well-established evidence that the dimensions of warmth/responsiveness and control are related differentially to both positive and negative outcomes for children, and continue to be discriminating throughout the adolescent years.

Although dimensions of parenting may look differently or be measured differently during emerging adulthood, we think it unlikely that key dimensions of parenting will be differentially related to positive outcomes during this time period. Hence, it was expected that warmth and control would be linked to child well-being in emerging adulthood in similar patterns as those seen during childhood and adolescence. In order to test this, variables were selected that would tap both adaptive and maladaptive outcomes, especially those that tend to be key developmental features of emerging adulthood (e.g., self-worth, risk taking, depression; see Arnett 2004). To tap adaptive outcomes, we examined the quality of the parent–child relationship, self-worth, social acceptance, and kindness. To tap maladaptive outcomes, we explored both externalizing problems (drinking and impulsivity) and internalizing problems (depression and anxiety). It was expected that parenting clusters reflecting greater warmth would be linked to higher levels of the adaptive behaviors and lower levels of both externalizing and internalizing problems. Conversely, we hypothesized that parenting in which warmth was lacking would be related to greater levels of maladaptive behaviors. Given the autonomy inherent in emerging adulthood, we found it difficult to make specific hypotheses regarding moderate levels of control, although we did expect excessive behavioral or psychological control to be related to negative child outcomes.

Finally, given mixed findings during childhood and adolescence, we deemed it important to explore whether there were parent and child gender differences in the links between parenting and child characteristics. Research on parenting during adolescence (Leaper 2002; Steinberg and Silk 2002) and emerging adulthood (McKinney and Renk 2008a, b) suggests that mothers and fathers do not always parent similarly, and that parenting is not always consistent for daughters and sons. Based on research on children and adolescents (Collins et al. 2002; Steinberg and Silk 2002), we expected mothers to display higher levels of warmth than fathers, and did not have specific expectations for differences in control given inconsistent gender differences found in existing research. In addition, research finds few consistent differences in parenting as a function of child gender (Steinberg and Silk 2002), so we did not have specific hypotheses in this regard, but felt it was important to explore.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from four universities and colleges across the United States, and included 403 emerging adults (M age = 19.89, SD = 1.78, range = 18–26, 62% female) and at least one of their parents (287 fathers and 317 mothers). Eighty-four percent of participants reported being European American, 6% Asian American, 4% African American, 3% Latino, and 4% reported being of other ethnicities. In terms of parental education, 66% of fathers and 60% of mothers reported having a bachelor’s degree or higher, and 50% of families reported a combined annual income of over $100,000 (M = 8.88, SD = 1.70, range = 1–10). Ninety percent of emerging adults reported living outside the parental home in a dormitory or apartment.

Procedure

Participants completed the Project READY (Researching Emerging Adults’ Developmental Years) questionnaire via the Internet (see http://www.projectready.net). The use of an online data collection protocol facilitated unified data collection across multiple university sites and allowed for the survey to be administered to emerging adults and their parents who were living in separate locations throughout the country. Participants were recruited through faculty’s announcement of the study in undergraduate courses. Informed consent was obtained online, and only after consent was given could the participants begin the questionnaires. Each participant was asked to complete a survey battery of 448 items. Most participants were offered course credit or extra credit for their own and their parents’ participation. After participants completed the personal information, they had the option to send an invitation (via e-mail) to their parents to participate in the study. Parents completed a shorter battery of 280 items similar to the ones their child completed, asking them to respond from a parental point of view. For more information on procedures, please see (Nelson et al. 2007).

Measures

In terms of parenting variables, the current study assessed child-reported psychological control and parental knowledge, and parent-reported punishment, verbal hostility, warmth, induction, autonomy granting, and indulgence. In terms of emerging adult outcomes, the current study assessed child-reported closeness, drinking, self-worth, social acceptance, kindness, depression, anxiety, and impulsivity; and parent-reported relationship quality.

Psychological Control

Psychological control was assessed using Barber’s (1996) measure of psychological control. Emerging adults rated eight statements regarding both their mothers' and fathers' current psychologically controlling behavior on a scale ranging from 1 (not like him/her) to 3 (a lot like him/her). Sample items include “He/She is always trying to change how I feel or think about things” and “He/She is less friendly with me if I do not see things his/her way”. Higher scores were indicative of higher levels of psychological control (α = .87 for fathers, .85 for mothers).

Parental Knowledge

Parental knowledge was assessed using Barber’s Regulation Scale (Barber et al. 1994). Emerging adults responded to eight questions regarding their mothers' and fathers' current knowledge of their behaviors (e.g., “Who my friends are” and “Whether I use drugs”) on a scale ranging from 1(doesn’t know) to 3 (knows a lot). Higher scores were indicative of higher levels of maternal (α = .79) and paternal (α = .84) knowledge.

Parenting Dimensions

The remainder of the parenting variables were assessed using a modified version of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ; Robinson et al. 1995). The original measure has been well established with young children, and consists of 62 items assessing seven dimensions of parenting. While the original measure was designed for parents of young children, many of the questions from Robinson et al.’s (1995) original measure were modified in the current study to be appropriate for emerging adults. For example, the induction item “I tell my child our expectations regarding behavior before the child engages in an activity” was changed to “I explain the reasons for our desires for our child (e.g., work, school, marriage).” Similarly, assessments of physical punishments, such as “Spanks child when child misbehaves” were replaced by items like “I grab our child when I don’t like what he/she does.”

The shortened adaptation used in the current study contained 41 items designed to assess dimensions of parenting during emerging adulthood, measured on a 5-point scale with responses ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Because items were reworded for parents of emerging adults, all items were factor analyzed (separately for mothers and fathers) to explore the dimensions of parenting during emerging adulthood. A factor loading of .40 was used as the criteria for determining substantial cross-loadings (Applebaum and McCall 1983), and items were dropped if they did not load on the same factor for both mothers and fathers (which only occurred for one item). Six subscales emerged that closely mirrored the original subscales of the Robinson et al. (1995) measure, with the exception of the punishment subscale, which was a combination of the punishment and non-reasoning/punitive dimensions from the original measure. The subscales included punishment (11 items, α mother = .82; α father = .86; e.g., “I kick our child out of the house as a way of punishing him/her”, “I punish by withholding some form of financial support”, and “I slap our child when there is a disagreement”), verbal hostility (4 items, α mother = .81; α father = .81; e.g., “I yell or shout when I disapprove of our child’s actions” and “I scold and criticize to make our child improve”), warmth/support (5 items, α mother = .74; α father = .83; e.g., “I am responsive to our child’s feelings or needs” and “I have warm and intimate times together with our child”; induction (4 items, α mother = .79; α father = .83; e.g., “I explain to our child how we feel about the child’s good and bad choices and actions” and “I give our child reasons for the expectations we have for him/her”), autonomy granting (5 items, α mother = .69; α father = .73; e.g., “I show respect for our child’s opinions by encouraging our child to express them” and “I allow our child to do what he/she thinks is best”), and indulgence (3 items, α mother = .62; α father = .58; e.g., “I spoil our child” and “I give into our child when the child causes a commotion about something”). Although the alphas for indulgence are relatively low, that was not unexpected given that internal consistency of scales is highly dependent upon length. The correlation between the indulgence items was >.25, which is typical for many well-used scales. Factor analysis also gave us confidence that these items were tapping the same aspect of parenting. Participating parents answered questions based on their own parenting, with higher scores indicative of higher levels of that dimension of parenting.

Parental Closeness

Parental closeness was measured using the Parent–Child Closeness Scale (Buchanan et al. 1991). Emerging adults responded to nine items assessing paternal and maternal closeness (18 items total). Sample items include, “How openly do you talk with your (father/mother)?”, and “How well does your (father/mother) know what you are really like?” Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very). Individual items were averaged for fathers and mothers, with higher scores representing greater parental closeness (α mother = .88, α father = .92).

Parent–Child Relationship Quality

The short-version of the Social Provisions Questionnaire (Carbery and Buhrmester 1998) was used to assess the quality of the parent–child relationship. Parents rated 27 items regarding their relationship with their child. Sample items include, “How happy are you with the way things are between you and your child?”, and “How sure are you that your relationship with this person will last in spite of quarrels and fights?” Ratings were made on a 5-point scale that ranged from 1 (little or none) to 5 (the most). Cronbach’s alphas for parent–child relationship quality were .94 and .95 for mothers and fathers, respectively.

Drinking

Emerging adults’ drinking behavior was measured using two items from the Add Health Questionnaire (www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth/). Emerging adults were asked how many days in the past 12 months they drank alcohol and engaged in binge drinking (i.e., 4–5 drinks on one occasion). Participants rated these items on a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (none) to 5 (almost every day). The responses on these two items were averaged, with higher scores representing higher self-reported drinking (α = .90).

Self Worth and Social Acceptance

Emerging adults’ self worth (6 items) and social acceptance (5 items) were measured using the Self-Perception Profile (Neeman and Harter 1986). Items were rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1(not at all true for me) to 4 (very true for me). Sample items from the self worth and social acceptance subscales (respectively) include, “I like the kind of person I am” and “I am able to make new friends easily”. Higher scores were indicative of higher levels of self worth (α = .79) and social acceptance (α = .74).

Personal Characteristics

Emerging adults’ kindness (4 items), depression (3 items), anxiety (4 items), and impulsivity (2 items) were measured using corresponding subscales of the Adult Temperament Scale (Rothbart et al. 2000). Sample items for kindness included “kind” and “friendly”; items for depression included “hopeless” and “depressed”; items for anxiety included “worrier” and “tense”; and items for impulsivity included “easily irritated or mad” and “fight with others/lose temper”. On a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), participants responded to how often they would describe themselves in this manner. Items were averaged, with higher scores representing higher levels of self-reported kindness (α = .83), depression (α = .86), anxiety (α = .77), and impulsivity (α = .77).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

A number of t tests were conducted to determine if there were mean differences in parenting as a function of gender of the parent, and results found that 5 of the 8 analyses were statistically significant. Namely, results suggested that mothers (M = 2.38, SD = .44) had higher levels of child-reported parental knowledge than did fathers (M = 2.15, SD = .50), t(390) = 10.45, p < .001; fathers (M = 1.70, SD = .57) reported higher levels of punishment than did mothers (M = 1.61, SD = .46), t(188) = −2.76, p < .01; fathers (M = 2.06, SD = .72) reported higher levels of verbal hostility than did mothers (M = 1.92, SD = .63), t(194) = −2.41, p < .05; mothers (M = 4.27, SD = .48) reported higher levels of warmth than did fathers (M = 3.95, SD = .72), t(191) = 5.81, p < .001; and mothers (M = 4.12, SD = .62) reported higher levels of induction than did fathers (M = 3.91, SD = .76), t(194) = 3.25, p < .001.

A number of univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were also conducted to determine if parenting differed as a function of the gender of the child, and only 3 of the 16 analyses were statistically significant. Namely, young women (M = 2.45, SD = .42) reported higher maternal knowledge than did young men (M = 2.27, SD = .44), F(1, 394) = 15.95, p < .001; fathers reported using punishment more with sons (M = 1.80, SD = .68) than with daughters (M = 1.64, SD = .42), F(1, 304) = 6.11, p < .01; and fathers reported using verbal hostility more with sons (M = 2.21, SD = .85) than with daughters (M = 1.99, SD = .63), F(1, 297) = 6.17, p < .01.

Cluster Analysis

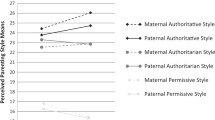

In the current study we used the Ward method of agglomeration with squared Euclidean distance. This approach attempts to maximize the differences between clusters by treating each individual case as a separate cluster and then combining the most similar clusters systematically until there is one all-inclusive cluster (Ward 1963). This procedure was conducted on the eight aspects of parenting (psychological control, punishment, verbal hostility, knowledge, warmth, induction, autonomy granting, and indulgence), separately for mothers and fathers. Prior to the analyses, scores on the parenting measures were standardized to ensure that classification would not be impacted by differences in scale variability. Because a definitive approach to determining the optimal number of clusters is not agreed upon (Milligan and Cooper 1985), we used a number of approaches. First, hierarchical dendrograms and agglomeration coefficients were examined. Dendrograms revealed that there were between 3 and 5 clusters for both mothers and fathers. When examining agglomeration coefficients, it is suggested that the number of clusters is determined based on the relative stability in change in the agglomeration coefficient from one stage to the next (Hair et al. 1998). Based on this criterion, the 4-cluster solution was more appropriate for both mothers and fathers. However, one of the objectives of hierarchical cluster analysis is to maximize interpretability, so we also carefully examined the 3- and 4-cluster solutions to determine whether they were meaningfully distinct on a conceptual level. For mothers, it appeared that Cluster 3 consisted of mothers with higher levels of negative parenting (punishment and verbal hostility), and high levels of indulgence compared to Cluster 4. Given the negative impact of harsh and permissive parenting during childhood and adolescence (see Hart et al. 2003), and a relative lack of knowledge regarding the impact of these aspects of parenting during emerging adulthood, it seemed meaningful to distinguish these two groups, so a 4-cluster solution was maintained for mothers. For fathers, it appeared that Cluster 3 consisted of fathers who were relatively near the mean on every aspect of parenting, while Cluster 4 consisted of fathers who were below the mean on negative and above the mean on positive aspects of parenting. Given that fathers in Cluster 4 had the highest levels of positive parenting of all four clusters, and in light of research supporting the importance of high levels of knowledge, warmth, induction, and autonomy granting during childhood and adolescence (see Hart et al. 2003), we thought this was a meaningful distinction to explore. Thus, for both mothers and fathers, a 4-cluster solution was retained (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Although clusters were calculated separately for mothers and fathers, parents had very similar patterns on 3 of the 4 clusters, so we will combine their descriptions where possible for parsimony. Cluster 1 M (n mothers = 46, 17%) and Cluster 1F (n fathers = 47, 18%) consisted of mothers and fathers (respectively) who had scores below the mean on all eight aspects of parenting [psychological control (−.37, −.19), punishment (−.39, −.07), verbal hostility (−.18, −.02), knowledge (−.36, −.18), warmth (−.89, −1.20), induction (−1.10, −1.32), autonomy (−.38, −1.08), and indulgence (−.20, .00)], so this cluster will be referred to as Uninvolved. Cluster 2 M (n mothers = 47, 17%) and 2F (n fathers = 19, 7%) consisted of mothers and fathers (respectively) who scored above the mean on both extremes of control [psychological control (1.55, 1.91), punishment (.73, 2.18), verbal hostility (.80, 1.76), and indulgence (.45, 1.00)], but scored below the mean on responsive parenting [knowledge (−.22, −.64), warmth (−.83, −.58), induction (−.70, −.20), and autonomy −1.03, −.77], so this cluster will be referred to as Controlling-Indulgent. Cluster 3 M (n mothers = 61, 22%) consisted of mothers who scored above the mean on positive aspects of parenting such as knowledge (.20) warmth (.56), induction (.43) and autonomy (.37), but also scored above the mean on negative aspects of parenting such as punishment (.29), verbal hostility (.38) and indulgence (.87). Because these mothers were using high levels of control, indulgence, and responsiveness, this cluster will be referred to as Inconsistent. Cluster 3F (n fathers = 121, 46%) consisted of fathers who scored near the mean on every aspect of parenting (.05, .01, .11, .01, .20, .29, .02, −.02), so this cluster will be referred to as Average. Cluster 4 M (n mothers = 120, 44%) and 4F (n fathers = 75, 29%) consisted of mothers and fathers (respectively) who scored above the mean on responsive parenting [knowledge (.18, .67), warmth (.38, .52), induction (.42, .43), and autonomy (.35, .71)], and below the mean on both extremes of control [psychological control (−.39, −.51), punishment (−.38, −.51), verbal hostility (−.48, −.63), and indulgence (−.56, −.23)], so this cluster will be referred to as Authoritative (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Mean Differences in Child Outcomes as a Function of Parental Cluster Membership

As further validation of the distinctions between parenting clusters, a number of ANOVAs were conducted to determine if parent–child relationship quality (assessed by child-reported closeness and parent-reported relationship quality) and child traits and behaviors (assessed by child-reported drinking behaviors, self-worth, social acceptance, kindness, depression, anxiety, and impulsivity) differed as a function of cluster membership. Initial models were conducted testing for interactions as a function of child gender, but none of the interactions were significant, so univariate ANOVAs were conducted for parsimony (see Table 1).

For mothers, authoritative and inconsistent mothers had higher levels of parent–child closeness (F(3, 268) = 12.35, p < .001) and relationship quality (F(3, 267) = 20.46, p < .001) than did uninvolved and controlling-indulgent mothers. Controlling-indulgent mothers had children with lower levels of self-worth than any of the other three clusters (who did not differ from one another), F(3, 270) = 6.96, p < .001. Uninvolved and controlling-indulgent mothers also had children who reported lower levels of social acceptance than did authoritative mothers, F(3, 270) = 3.88, p < .01. Authoritative mothers had children with higher scores on kindness than controlling-indulgent mothers (F(3, 270) = 2.68, p < .05), and controlling-indulgent mothers had children with higher levels of depression (F(3, 270) = 9.63, p < .001), anxiety (F(3, 270) = 6.34, p < .001), and impulsivity (F(3, 270) = 7.72, p < .001) than did any of the other three clusters (who did not differ from one another). Taken together, controlling-indulgent mothers seemed to have children with the most negative outcomes, while authoritative and inconsistent mothers had children with the most positive outcomes.

For fathers, authoritative fathers had the highest levels of parent–child closeness, followed by average, uninvolved, and controlling-indulgent parents, F(3, 257) = 23.65, p < .001. Authoritative and average fathers also reported higher relationship quality with their child than did uninvolved or controlling-indulgent fathers (who did not differ from one another), F(3, 249) = 11.20, p < .001. Authoritative and average fathers had children who reported higher levels of drinking behavior than did uninvolved and controlling-indulgent fathers (who did not differ from one another), F(3, 258) = 3.45, p < .05. Authoritative fathers had children with the highest levels of self-worth (F(3, 258) = 9.37, p < .001) and kindness (F(3, 258) = 7.82, p < .001), and controlling-indulgent fathers had children with the lowest levels of self-worth and kindness (with no differences between uninvolved and average). Authoritative fathers also had children with higher levels of social acceptance than did controlling-indulgent and average fathers (who did not differ from one another), F(3, 258) = 4.29, p < .01. Finally, controlling-indulgent fathers had children with the highest levels of depression (F(3, 258) = 6.72, p < .001) and anxiety (F(3, 258) = 3.04, p < .05), and also had children with marginally higher levels of impulsivity than did authoritative fathers, F(3, 258) = 2.33, p = .07. Taken together, controlling-indulgent fathers seemed to have children with the most negative outcomes, while authoritative fathers had children with the most positive outcomes.

Discussion

In the United States, the majority of 18–29 year olds attending college do not consider themselves to be adults, nor do their parents consider them to be adults (e.g., Arnett 2000; Nelson et al. 2007). Therefore, many parents may feel they still need to be engaged in “parenting” activities that help their children navigate this period of experimentation and exploration (Arnett 2000), while at the same time allowing them the independence they want and need. However, few studies have examined what these parenting behaviors may be during emerging adulthood. Thus, the purpose of this study was to examine dimensions of parenting used by parents of emerging-adult children. Specifically, the study attempted to identify different clusters of parents based on the extent to which they exhibited both extremes of control (psychological control, punishment, verbal hostility, indulgence) and warmth/responsiveness (knowledge, warmth, induction, autonomy granting). Results revealed four clusters of parenting for both mothers and fathers (three of which were very similar across parents), and these clusters were related to differences in emerging adult children’s adaptive and maladaptive outcomes.

Parenting Clusters During Emerging Adulthood

Results for both mothers and fathers identified three similar clusters of parents which we labeled as uninvolved (low on all aspects of parenting), controlling-indulgent (high on both extremes of control and low on all aspects of responsiveness), and authoritative (high on responsiveness and low on control). A fourth cluster was identified for both mothers and fathers and was labeled as inconsistent for mothers (mothers were above the mean on both extremes of control and on responsiveness) and average for fathers (fathers were at the mean on all eight aspects of parenting). Although authoritative and uninvolved parents are similar to parenting styles seen during childhood and adolescence, these findings suggest that perhaps new approaches to parenting are used during emerging adulthood, given the unique challenges of parenting a child who is seeking independence and in many cases no longer lives in the home, but who is still dependent on parents.

Findings also suggested that these clusters were related to different child outcomes. For mothers, there were no differences on child outcomes between authoritative and inconsistent mothers, suggesting that at least on the outcomes measured in the current study, types of mothering that contained warmth/responsiveness (even if they were accompanied by moderate control and indulgence, such as was the case with inconsistent mothers) were similarly associated with positive outcomes. Thus, authoritative and inconsistent mothers had emerging-adult children with more positive outcomes on the majority of variables assessed. Conversely, controlling-indulgent mothers had children with the most negative child outcomes, with the lowest levels of parent–child closeness and self-worth, and the highest levels of depression, anxiety, and impulsivity. In turn, controlling-indulgent and uninvolved mothers did not have children who differed from one another in having lower scores on relationship quality with mother, social acceptance, and kindness; suggesting that uninvolved mothering was not as detrimental as controlling-indulgent mothering, but was still associated with a number of negative outcomes for the child. Taken together, this suggests that during emerging adulthood one of the least adaptive approaches to parenting is one in which punishment or control is high, and warmth/responsiveness is low. Although parental control is rarely adaptive, given the autonomy that is necessary when children leave the parental home to go to college, it appears that parental attempts to maintain control may be particularly unwelcome during emerging adulthood. Indeed, even disengagement or lack of involvement may be relatively more adaptive than a controlling approach because of the developmental importance of becoming an independent person during this period of life.

Results revealed similarly significant links between parenting of fathers and child characteristics. As with mothers, authoritative fathers had children with the most consistently positive outcomes, with the highest levels of parent–child closeness, self-worth, social acceptance and kindness; and the lowest levels of depression. As might be expected, average fathers had slightly less positive child outcomes compared to authoritative fathers, but not as many negative outcomes as controlling-indulgent and uninvolved fathers. Notably, average fathers did not differ from authoritative fathers on relationship quality, suggesting that the slight elevations in warmth and induction characteristic of average fathers might slightly overshadow the moderate levels of other aspects of parenting. Similar to mothers, however, controlling-indulgent fathers were consistently related to the worst child outcomes, with the lowest levels of parent–child closeness, self-worth, and kindness; and the highest levels of depression and anxiety. Although slightly less negative, uninvolved fathering did not differ from controlling-indulgent fathering in having lower relationship quality.

These findings make a significant contribution to the literature because although research has found fathers to be uniquely important in children’s development (e.g., Day and Padilla-Walker 2008), most studies on parenting, including those sampling emerging adults, have only examined characteristics and behaviors of mothers (e.g., Manzeske and Stright 2009). Results from the current study suggest that important differences are present in the mothering and fathering behaviors of parents with emerging adult children. On average, mothers used more inductive strategies, demonstrated more warmth, and were more involved (as seen by having more knowledge of their children’s lives) than fathers. Fathers, on the other hand, tended to demonstrate higher levels of punishment and verbal hostility than did mothers. These findings are in line with parenting research on younger children indicating that mothers are generally viewed by their children as using induction more than other discipline techniques (Barnett et al. 1996), but adds to existing research by finding that fathers were higher on some aspects of control than were mothers. In addition to mean differences in parenting characteristics, the largest majority of mothers (44%) fell into the authoritative parenting cluster, whereas the largest majority of fathers (46%) were grouped in the average parenting cluster, indicating that mothers and fathers may be approaching the parenting of their emerging-adult children differently. Taken together, the results of this study provide some of the first insight into differences between mothers and fathers in their parenting during emerging adulthood.

The findings of this study also provide important evidence regarding the links between the parenting of mothers and fathers and their children’s characteristics during this period of time. Specifically, while there were some differences between mothers and fathers across the various dimensions examined, the pattern of outcomes tended to be similar for mothers and fathers. Overall, regardless of the gender of the parent, authoritative parenting was linked to positive outcomes while controlling-indulgent parenting was linked to numerous negative child outcomes.

Taken together, it appears that several parenting dimensions cluster in a way that can be identified as distinct and separate approaches to parenting of emerging adults, and that these clusters distinguish between child outcomes. It should be noted that at the outset of the study, it was not necessarily expected that parenting styles typically measured at younger ages (e.g., authoritative and authoritarian) would emerge from the parenting dimensions measured. Because so little is known about parenting in emerging adulthood, we were simply interested in examining specific dimensions of parenting (i.e., aspects of control and warmth/responsiveness) that were considered potentially important during this time period. Therefore, it was interesting to see both similarities and differences between the clusters that emerged in this study, and parenting styles identified during other periods of development. Recent work by Wintre and Yaffe (2000) and McKinney and Renk (2008a, b) has examined authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting in emerging adulthood. However, as noted previously, the scale (Parental Authority Questionnaire—PAQ; Buri, 1991) they employed was originally designed for emerging adults to provide a retrospective assessment of what their parents did while the children were growing up. Therefore, there is little evidence to suggest that the PAQ taps dimensions of parenting that are relevant in emerging adulthood. Hence, the current study is one of the first to use a measure designed to specifically tap ways that warmth and control may be exhibited during emerging adulthood and in doing so supports the notion that, as in other periods of development, parenting that comprises warmth, induction, knowledge, and autonomy granting appears to be linked to positive development in children (e.g., higher self-worth, more positive self-perceptions, kindness), and to be beneficial for the parent–child relationship. Conversely, approaches to parenting that employ punishment, psychological control, verbal hostility, and indulgence are related to negative aspects of development (e.g., depression, anxiety) and lower quality relationships with parents.

It should be noted, however, that the clusters that emerged in the current study did not fit perfectly the typical profiles of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting as seen in childhood and adolescence. For example, there were parents who displayed verbally hostile and punishing behaviors as well as indulgent behaviors; some in the presence of warmth (inconsistent) and some not (controlling indulgent). This may suggest that while certain parenting dimensions appear to still be positive (warmth, autonomy, induction) or negative (punishment, control, hostility) and, therefore, relevant in the study of parenting during emerging adulthood, it may not be possible to use all of the broad classifications applied to parenting during previous periods of development (with the notable exceptions of authoritative and uninvolved parenting). It also could be suggested that any approach to parenting that contains above-average levels of warmth and induction appears to be relatively more adaptive during emerging adulthood, regardless of the other aspects of parenting used in combination. This suggests that parents are most effective during emerging adulthood when they talk to their children and do what they can to maintain the relationship, while simultaneously granting greater levels of autonomy and forming new boundaries that are based substantially less on parental control.

Relevance of Parenting in Emerging Adulthood

Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, it might be argued that the results simply reflect the residual effects of years of parenting. For example, it may be that the close relationship between children and their authoritative parents is not due to present parenting, but the years of positive parenting when the emerging adult was a child and adolescent. Certainly, as in any time period, the current state of the relationship is related to previous interactions. However, just as parents of toddlers need to adapt their parenting (i.e., grant more autonomy, display warmth in different ways, etc.) as their children enter childhood and later adolescence, parents need to adapt to the unique demands of emerging adulthood. Specifically, emerging adulthood has been described by young people (e.g., Arnett 2006; Badger et al. 2006; Nelson and Barry 2005; Nelson et al. 2007) and parents (Nelson et al. 2007) as a time of transition during which young people are not yet considered to be adults, but are striving to become independent, self-reliant individuals, while simultaneously establishing an equal relationship with parents. Indeed, Nelson et al. (2007) found that only one item was endorsed more by young people as being necessary for becoming an adult than “establish relationship with parents as an equal adult.” Taken together, both parents and children feel this is a period of change and transition in the parent–child relationship, and thereby feel a need for parents to again change how they parent their children while still playing an important role in their lives. Indeed, young people want to become more independent and self reliant and also want their relationship with their parents to change (“establish relationship with parent as an equal adult”; Nelson et al. 2007), but in a way that will lead to more of a relationship, not less. The results of the current study suggest approaches to parenting during emerging adulthood (not just during prior stages of development) that may foster both of these criteria deemed important by young people.

The results may also be capturing the changing nature of the parent–child relationship in that some parents appeared to be experimenting with their parenting during this time period, as some parents showed both controlling and indulgent behaviors, and others showed both warm and controlling techniques. It may be that parents know that their parenting needs to change in order to bring about the milestones of the time period (child independence, an equal relationship between parent and child, etc.; e.g., Nelson et al. 2007) but they are not quite sure how to best do that. As a result, some parents may appear to be too controlling in some areas and indulgent in others areas as they attempt to achieve appropriate levels of autonomy and control. Still other parents may simply believe that once children graduate from high school they are on their own (i.e., uninvolved). In sum, the complexity of the changes in the parent–child relationship during this time period may be a reason why broad typologies of parenting (e.g., authoritarian, permissive) cannot describe what is happening. However, this same complexity may underscore the importance of examining specific dimensions of parenting (e.g., warmth, hostility, autonomy) in emerging adulthood. Future work should begin to examine the motivations behind the behaviors parents use during this time in order to better understand the parenting approaches they employ.

Future research also needs to examine the direction of effects in the relations between parenting and child outcomes, as the cross-sectional nature of the current study could not determine causality. It may be that as parents provide autonomy while still showing warmth and support, their children feel close to them and keep them informed (i.e., knowledge) of the things going on in their lives (Padilla-Walker et al. 2008), which helps facilitate positive development. Conversely, the verbally hostile, punitive, and controlling parent may hinder both the independence and change in the parent–child relationship that young people want at this age. Finally, the bi-directionality of the parent–child relationship should be examined to see how child characteristics may be influencing the way parents choose to interact with their children. Such a perspective might guide work that further explicates the mechanisms by which some parents (i.e., inconsistent) engage in both positive and negative aspects of parenting, and how they either affect or are affected by child characteristics.

Finally, future work should investigate what the effects may be on emerging-adult children when parents engage in different types of parenting. In assessing children’s perceptions of their mothers’ and fathers’ parenting, McKinney and Renk (2008a) found that authoritative parenting by at least one parent led to better emotional adjustment in emerging-adult children but they did not directly examine the extent to which each set of parents were similar or different in their parenting and the extent to which the similarities or differences were linked to child outcomes. Hence, further work is need to assess whether or not at least one warm, supportive parent is sufficient to produce positive outcomes, or if a rather negative experience with even one parent may be enough to, for example, drive a child away from his or her parents in an attempt to achieve greater independence.

Limitations

The study was not without limitations. First, the sample consisted of college students, and therefore may not be generalizable to a non-student population. There is still relatively little that is known about individual differences in the “forgotten half” (young people who do not attend college after high school; Willliam and Grant Foundation commission on Work, Family, Citizenship 1988), and even less about their parents. Young people who attend college tend to come from higher socio-economic status (SES) families (Pell Institute 2004) and research has shown that parenting styles tend to vary as a function of SES (see Hoff et al. 2002, for a review). Therefore, it is possible that clusters of parenting dimensions may differ in parents of children who do not attend college. However, the results of the current study provide an important foundation from which future work can be conducted examining approaches to parenting with non-college populations. Furthermore, given that two-thirds of young people in the United States enter college the year following high school (National Center for Education Statistics 2002, Table 20–2), findings from the present study may be relevant for a good portion of young people and their parents in the United States.

Second, the participants lacked ethnic diversity. Theoretical and empirical work has shown the importance of examining how parenting is affected by larger sociocultural contexts and conditions such as poverty, segregation, racism, belief/value systems, and acculturation (e.g., Harrison et al. 1990; Taylor 2000). This body of work suggests that what may be considered adaptive or maladaptive in one setting may be reversed in another context. Therefore, there is a need to replicate these findings in more ethnically diverse samples.

Next, as stated previously, a notable limitation is the correlational nature of the study, which precludes causal inferences. Whereas we have speculated at times in the discussion about possible causal processes, the data prevented us from making conclusive statements. Indeed, although we have often discussed possible scenarios in which parenting may lead to the child characteristics found in the study, it may be that child characteristics are influencing parenting. There is a plethora of work with young children showing that child characteristics (e.g., temperament, behavior) predict parenting behavior (e.g., Rubin et al. 1999; Russell 1997). Less work has been done with older children, especially in emerging adulthood, to examine ways in which child characteristics may lead to certain parenting behaviors and approaches. There is certainly a need for further research in this area.

Conclusion

Overall, this study makes several unique contributions to our understanding of parenting in emerging adulthood. Most notably, it is one of the first studies examining potentially important dimensions of parenting and how they cluster together to produce different approaches to parenting in emerging adulthood. The findings indicate that warmth/responsiveness and control remain central components in the parent–child relationship and in relation to child outcomes in emerging adulthood. Indeed, these findings suggest that parenting in emerging adulthood may be linked to important aspect of young people’s development during a period of extensive transition, thereby underscoring the need for researchers to examine the role that parenting may play during this unique time in children’s lives, and serving as a significant starting point for such work to be conducted in the future.

References

Applebaum, M. I., & McCall, R. B. (1983). Design and analysis in developmental psychology. In P.H. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (4th ed.), Vol. 1, W. Kessen (Volume Ed.), History, theory, and methods (pp. 415–471). New York: Wiley.

Aquilino, W. S. (1996). The returning adult child and parental experience at midlife. In C. D. Ryff & M. M. Seltzer (Eds.), The parental experience in midlife (pp. 423–458). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Aquilino, W. S. (1997). From adolescent to young adult: A prospective study of parent–child relations during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 59(3), 670–686.

Aquilino, W. S. (2006). Family relationships and support systems in emerging adulthood. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 193–217). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. NY: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2006). Emerging adulthood: Understanding the new way of coming of age. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 3–20). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Badger, S., Nelson, L. J., & Barry, C. M. (2006). Perceptions of the transition to adulthood among Chinese and American emerging adults. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 84–93.

Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296–3319.

Barber, B. K., Olsen, J. E., & Shagle, S. C. (1994). Associations between parental psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behaviors. Child Development, 65, 1120–1138.

Barnett, M., Quackenbush, S., & Sinisi, C. (1996). Factors affecting children’s, adolescents’, and young adults’ perceptions of parental discipline. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 157, 411–424.

Barry, C., Padilla-Walker, L., Madsen, S., & Nelson, L. (2008). The impact of maternal relationship quality on emerging adults’ prosocial tendencies: Indirect effects via regulation of prosocial values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(5), 581–591.

Baumrind, D. (1967). Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 75, 43–88.

Baumrind, D. (1978). Reciprocal rights and responsibilities in parent-child relations. Journal of Social Issues, 34, 179–196.

Baumrind, D. (1991). Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In P. A. Cowan & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Family transitions (pp. 111–163). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Baumrind, D., & Black, A. E. (1967). Socialization practices associated with dimensions of competence in preschool boys and girls. Child Development, 38(2), 291–327.

Berzonsky, M. (2004). Identity style, parental authority, and identity commitment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33(3), 213–220.

Buchanan, C. M., Maccoby, E. E., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Caught between parents: Adolescents’ experience in divorced homes. Child Development, 62, 1008–1029.

Buhl, H. (2007). Well-being and the child-parent relationship at the transition from university to work life. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22(5), 550–571.

Buri, J. R., Louiselle, P. A., & Misukanis, T. M. (1988). Effects of parental authoritarianism and authoritativeness of self-esteem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14, 271–282.

Carbery, J., & Buhrmester, D. (1998). Friendship and need fulfillment during three phases of young adulthood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15, 393–409.

Collins, W. A., Madsen, S. D., & Susman-Stillman, A. (2002). Parenting during middle childhood. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1: Children and parenting (2nd ed., pp. 103–133). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Day, R. D., & Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2008). Mother and father connectedness and involvement during early adolescence. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Dominguez, M., & Carton, J. (1997). The relationship between self-actualization and parenting style. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 24, 1093–1100.

Gomez, R., & McLaren, S. (2006). The association of avoidance coping style, and perceived mother and father support with anxiety/depression among late adolescents: Applicability of resiliency models. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1165–1176.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Harrison, A. O., Wilson, M. N., Pine, C. J., Chan, S. Q., & Buriel, R. (1990). Family ecologies of ethnic minority children. Child Development, 61, 347–362.

Hart, C. H., Newell, L. D., & Olsen, S. F. (2003). Parenting skills and social-communicative competence in childhood. In J. O. Greene & B. R. Burleson (Eds.), Handbook of communication and social interaction skills (pp. 753–797). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hoff, E., Laursen, B., & Tardif, T. (2002). Socioeconomic status and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 2 Biology and ecology of parenting (pp. 231–254). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kenny, M., & Sirin, S. (2006). Parental attachment, self-worth, and depressive symptoms among emerging adults. Journal of Counseling & Development, 84(1), 61–71.

Leaper, C. (2002). Parenting girls and boys. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1: Children and parenting (2nd ed., pp. 189–226). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Leondari, A., & Kiosseoglou, G. (2002). Parental, psychological control and attachment in late adolescents and young adults. Psychological Reports, 90(3), 1015–1030.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In P. H. Mussen (Ed.) & E. M. Hetherington (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed., pp. 1–101). New York: Wiley.

Manzeske, D. P., & Stright, A. D. (2009). Parenting styles and emotion regulation: The role of behavioral and psychological control during young adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 16, 223–229.

Masten, A. S., Burt, K. B., Roisman, G. I., Obradovic, J., Long, J. D., & Tellegen, A. (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: Continuity and change. Development & Psychopathology, 16, 1071–1094.

McKinney, C., & Renk, K. (2008a). Differential parenting between mothers and fathers: Implications for late adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 29(6), 806–827.

McKinney, C., & Renk, K. (2008b). Multivariate models of parent-late adolescent gender dyads: The importance of parenting processes in predicting adjustment. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 39(2), 147–170.

Milligan, G. W., & Cooper, M. C. (1985). An examination of procedures determining the number of clusters in a data set. Psychometrika, 50, 159–179.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2002). The condition of education, 2002. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. Available: www.nces.gov.

Neeman, J., & Harter, S. (1986). Manual for the self-perception profile for college students. Unpublished manuscript, University of Denver: Denver, CO.

Nelson, L. J., & Barry, C. M. (2005). Distinguishing features of emerging adulthood: The role of self-classification as an adult. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20, 242–262.

Nelson, L., Padilla-Walker, L., Carroll, J., Madsen, S., Barry, C., & Badger, S. (2007). ‘If you want me to treat you like an adult, start acting like one!’ Comparing the criteria that emerging adults and their parents have for adulthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 665–674.

Openshaw, D. K., Thomas, D. L., & Rollins, B. C. (1984). Parental influences of adolescent self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence, 4(3), 259–274.

Padilla-Walker, L., Nelson, L., Madsen, S., & Barry, C. (2008). The role of perceived parental knowledge on emerging adults’ risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(7), 847–859.

Patock-Peckham, J. A., & Morgan-Lopez, A. A. (2009). The gender specific meditational pathways between parenting styles, neuroticism, pathological reasons for drinking, and alcohol-related problems in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 34, 312–315.

Pell Institute. (2004). Indicators of opportunity in higher education. Washington, D.C.: Pell Institute.

Roberts, W. L. (1986). Nonlinear models of development: An example from the socialization of competence. Child Development, 57, 1166–1178.

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77, 819–830.

Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., & Evans, D. E. (2000). Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 122–135.

Rubin, K. H., Nelson, L. J., Hastings, P., & Asendorpf, J. (1999). The transaction between parents’ perceptions of their children’s shyness and their parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 23, 937–957.

Russell, A. (1997). Individual and family factors contributing to mothers’ and fathers’ positive parenting. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 21, 111–132.

Schnaiberg, A., & Goldenberg, S. (1989). From empty nest to crowded nest: The dynamics of incompletely launched young adults. Social Problems, 36, 251–269.

Smits, I., Soenens, B., Luyckx, K., Duriez, B., Berzonsky, M., & Goossens, L. (2008). Perceived parenting dimensions and identity styles: Exploring the socialization of adolescents’ processing of identity-relevant information. Journal of Adolescence, 31(2), 151–164.

Steinberg, L., Blatt-Eisengart, I., & Cauffman, E. (2006). Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful homes: A replication in a sample of serious juvenile offenders. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 47–58.

Steinberg, L., & Silk, J. S. (2002). Parenting adolescents. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1: Children and parenting (2nd ed., pp. 103–133). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Taylor, R. L. (2000). Racial, ethnic, and cultural diversities in families. In D. H. Demo, K. R. Allen, & M. A. Fine (Eds.), Handbook of family diversity (pp. 232–251). New York: Oxford University Press.

Tubman, J., & Lerner, R. (1994). Affective experiences of parents and their children from adolescence to young adulthood: Stability of affective experiences. Journal of Adolescence, 17, 81–98.

Turner, E. A., Chandler, M., & Heffer, R. W. (2009). The influence of parenting styles, achievement motivation, and self-efficacy on academic performance in college students. Journal of College Student Development, 50, 337–346.

Ward, J. H. (1963). Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 58, 236–244.

Whitbeck, L., Hoyt, D., & Huck, S. (1994). The effects of early family relationships on contemporary relationships and assistance patterns between adult children and their parents. Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 49, 85–94.

Willliam, T., & Grant Foundation commission on Work, Family, Citizenship. (1988). The forgotten half: Non-college-bound youth in America. Washington, DC: William T. Grant Foundation.

Wintre, M. G., & Yaffe, M. (2000). First-year students’ adjustment to university life as a function of relationships with parents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15, 9–37.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Carolyn McNamara Barry and Stephanie Madsen for their extensive help on Project READY. The authors also express appreciation to the instructors and students at all Project READY data collection sites for their assistance. We are grateful for the grant support of the Family Studies Center at Brigham Young University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nelson, L.J., Padilla-Walker, L.M., Christensen, K.J. et al. Parenting in Emerging Adulthood: An Examination of Parenting Clusters and Correlates. J Youth Adolescence 40, 730–743 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9584-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9584-8