Abstract

Relative to the merits of authoritative parenting, potential adverse outcomes are well documented for authoritarian and permissive parenting. However, conclusions are typically drawn from single informants. The ability of youths’ emotion regulation skills to mediate outcomes in emerging adults has also not been fully explored. This study investigated whether emotion regulation mediated parenting style history and potential outcomes of mental health and delinquency. Parenting style history and emerging adults’ emotion regulation ability were reported by 110 youth and their caregivers; youth reported on mental health functioning and delinquency. Emerging adults’ emotion regulation ability partially mediated the association between authoritative parenting history and mental health functioning and authoritative parenting history was indirectly related to delinquency through emotion regulation; however, based on all reporters, emotion regulation ability was not associated with authoritarian or permissive parenting style history. Results support that the merits of authoritative parenting may lie in fostering better emotion regulation skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parents’ attitudes, values, and parenting practices have demonstrable effects on an array of child outcomes. Parenting styles, the sustained climate and approach parents adopt in child-rearing, are among the most frequently researched parenting dimensions, derived from the classic conceptualization of parenting styles that differ on two dimensions: warmth/responsiveness and control/demandingness (Baumrind 1966, 1971). Authoritative parenting, characterized by firm limits and demands within the context of parental warmth, is typically considered optimal for child development (Larzelere et al. 2013). In contrast, high demands without parental warmth is deemed authoritarian parenting whereas minimal demands within the context of high warmth is considered permissive parenting (Robinson et al. 1995). Compared to the optimal outcomes observed with authoritative parenting, these alternative parenting strategies have traditionally evidenced relatively poorer outcomes for children (Baumrind 1966, 1971).

More recent evidence continues to highlight the benefits of authoritative parenting. For example, authoritative parenting was predictive of adaptive toddler behavior whereas maternal permissive and paternal authoritarian parenting styles predicted children’s externalizing behavior (Rinaldi and Howe 2012). Relative to other parenting styles, authoritative parenting was associated with the best adolescent emotional and behavioral outcomes (Panetta et al. 2014) whereas authoritarian parenting has been linked with delinquent adolescent behaviors (Bronte-Tinkew et al. 2006). The relative advantages of authoritative parenting has even been observed cross-culturally, wherein a Hungarian sample of adolescents with more authoritative parenting displayed fewer adolescent mood problems (Piko and Balazs 2012). Some have posited authoritarian approaches may not be adverse for children in certain ethnic/racial groups (e.g., Baumrind 1972); however, others have identified authoritative parenting is linked with better outcomes (i.e., in terms of lower depression and smoking as well as academic achievement) in a large sample of Caucasian, Hispanic, African-American, and Asian adolescents (Radziszewska et al. 1996), and authoritative parenting predicts fewer behavior problems in African-American children (Querido et al. 2002). Therefore, the preponderance of evidence suggests authoritative parenting style during a child’s upbringing ultimately promotes positive functioning across the lifetime. What remains unclear is the mechanisms whereby authoritative parenting may facilitate such adaptive outcomes.

One potential mechanism may be emotion regulation, considered the process whereby emotions, both negative and positive, are effectively identified, monitored, managed, and modified, both internally and externally (Thompson 1994). A high level of parental supportiveness, reflective of an authoritative parenting style, theoretically fosters acceptance of children’s displays of emotion compared to the dismissal of emotion expression in authoritarian parenting (Chan et al. 2009). Consequently, parenting style may influence the evolution of children’s emotion regulation abilities (Morris et al. 2007).

Indeed, adolescents with low levels of parental nurturance display greater current depression and demonstrate poorer emotion regulation as well (Betts et al. 2009). Perceived high parental psychological control and low parental supportiveness (qualities related to authoritarian parenting style) were associated with college youth’s current alcohol use mediated by poor emotion regulation (Fischer et al. 2007). Qualities characteristic of emotion regulation mediate the relation between parental warmth and fewer externalizing problems across time (Eisenberg et al. 2005). Such outcomes echo findings that adolescents’ emotion regulation mediated their history of parental warmth and lower externalizing problems (Walton and Flouri 2010). Reported history of higher maternal behavioral control was also associated with problematic emotion regulation among youth in one of the few studies to consider both emotion regulation and parenting style dimensions in emerging adults (Manzeske and Stright 2009). Another study examined adolescents, reporting on parenting style history from both parents as well as temperamental factors considered elements that reflect emotion regulation abilities; findings suggested that for both maternal and paternal parenting, authoritative parenting history was associated with better emotion regulation, permissive parenting style history was associated with poorer emotion regulation, but authoritarian parenting style was unrelated to adolescents’ emotion regulation abilities (Jabeen et al. 2013). Consequently, the collective evidence suggests adaptive parenting styles like authoritative parenting might promote the development of better emotion regulation in children which in turn would enhance later functioning.

Therefore, the current study aimed to investigate whether emotion regulation ability mediated the association between parenting style history and mental health and delinquency in a sample of emerging adults. Although a number of studies have considered parenting beliefs among childless college students, parenting style history and emotion regulation in conjunction with this collection of presumptive outcomes has not been evaluated in this age group. Yet late adolescents are proximal to the parenting style they actually received, minimizing retrospective recall concerns. Based on prior findings and the belief that parenting influences emotion regulation abilities which in turn affect later adjustment, emerging adults’ poorer mental health and greater delinquency were expected to be positively associated with authoritarian and permissive parenting style history and negatively associated with authoritative parenting style history, mediated by their emotion regulation ability.

A major methodological design limitation, however, dominates the extant literature on parenting style: a dependence on a sole reporter to assess parenting style history and potential outcomes, restricting the viewpoints considered as well as contributing to method bias, despite evidence of limitations in single-source reporting (e.g., Rinaldi and Howe 2012). Reliance on child-reports alone may convey one person’s perspective on the parenting received, although sole reliance on the alternative perspective of parents is also not impartial. Moreover, parenting style history may be constrained to reports about what one received from one parent (typically mothers) in assessing parenting style history (e.g., Stright and Yeo 2014), whereas other researchers have at least attempted to assess parenting style history received from both parents, either by child report (e.g., Jabeen et al. 2013; Panetta et al. 2014) or parent report (e.g., Rinaldi and Howe 2012). Research has been equivocal regarding whether fathers’ parenting styles may result in different outcomes for children (e.g., Casas et al. 2006), although others highlight some of the congruencies between maternal and paternal parenting styles (e.g., Davidov and Grusec 2006; Rinaldi and Howe 2012). One rare study actually assessed emotion regulation ability based on emerging adults’ self-report and, independently, parenting style history from a little less than half of their mothers (Manzeske and Stright 2009). Thus, the bulk of the conclusions drawn about potential outcomes associated with parenting style history derive from narrow sources of information that can be confounded by source bias. To address the drawbacks of relying on individual reporters, the current study adopted a multi-informant approach to assess the parenting style histories as well as the emotion regulation abilities of emerging adults, including the emerging adults’ reports of both parents’ styles as well as the reports of those parents. This effort to secure a more comprehensive assessment of these critical variables was intended to achieve a more balanced perspective of both emotion regulation ability and parenting style history that would be more inclusive of different viewpoints and less subject to methodological bias.

Method

Participants

The sample included 110 emerging adults enrolled in introductory psychology in a medium-sized public university in the Southeast. The sample was 75.5 % female, predominantly Caucasian (74.5 %, with 16 % African-American, 3 % Hispanic, 3 % Asian, ~4 % Other) and restricted to childless students between ages 18–20 (M = 18.8 years); age maximum was selected so that they would be most recently parented by these caregivers and childlessness was required to avoid confounding with personal parenting style. For reported maternal caregiver relationship, 95.5 % were biological mothers, with an additional 2.7 % stepmothers, one student raised by a grandmother, and one raised solely by a paternal caregiver. For paternal caregivers, 82.7 % reported on a biological father, 10 % on a stepfather, 1.8 % an adoptive father, and one on their mother’s boyfriend (the remaining five did not have a father-figure). We were able to secure 106 maternal caregiver reports and 80 paternal caregiver reports (n = 79 with three reporters). Because a small number reported being raised by a single caregiver, analyses by single- versus dual-parent were not conducted.

Procedure

The current study involved three separate phases to minimize response set wherein responses on one measure exert undue influence on responding to another measure. First, during a group pre-screening session available to all introductory psychology students, participants completed a measure of parenting style history for both primary caregivers as part of a large, diverse collection of questionnaires. Several weeks later, in a second phase, childless participants between the ages of 18–20 were invited to participate without an explicit connection to the parenting style questionnaires completed in prescreening. Interested students then provided consent for this study and provided email contact information for both caregivers. An online survey using Qualtrics containing the parenting style history measure and the parent’s evaluation of their child’s emotion regulation abilities was sent to caregivers’ individual email addresses. Only when at least one caregiver had completed their online survey would the student be invited to return for a third individual session, during which participants would complete a larger computerized study that included measures of their emotion regulation ability, mental health functioning, and past delinquent behavior. This electronic delivery system allowed us to avoid missing data from individual items. Moreover, the collection of the emerging adults’ parenting style history was separated in time from their report of their remaining measures by at least a month or more. Participants were awarded credit for research participation as part of their introductory psychology class. All procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Parental Authority Questionnaire-Revised (PAQ)

The PAQ is a 30-item measure of parenting style frequently used with college student populations, designed to assess authoritarian, authoritative, or permissive parenting styles (Buri 1991; Reitman et al. 2002). Sample items include: “Once family rules were made, my parent discussed the reasons for the rules with me” (Authoritative); “My parent did not allow me to question the decisions that they made” (Authoritarian); and, “I was allowed to decide most things for myself without a lot of help from my parent” (Permissive). Each parenting style is captured with 10 items utilizing a 5-point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” with total scores summed and oriented such that higher scores indicate greater display of that particular style. Internal consistency reportedly ranges from .72 to .76 for Authoritarian and Permissive scales, although the Authoritative scale demonstrated more variable alpha coefficients (.56 to .77); retest reliability for Authoritative, Authoritarian, and Permissive parenting scales was reported as .54, .88, and .74, respectively (Reitman et al. 2002).

In the current study, emerging adults completed the retrospectively-worded version of the PAQ for both their maternal and paternal caregivers, with the standard PAQ items self-reported by the two caregivers themselves. For the current sample, internal consistencies across parenting style scales and reporters were acceptable (see Table 1).

Negative Mood Regulation Scale (NMRS)

The NMRS (Catanzaro and Mearns 1990) is a 30-item self-report measure designed to assess one’s general ability to regulate negative emotions. Each item begins with, “When I’m upset, I believe that…” followed by the potential strategy (e.g., “Doing something nice for someone else will cheer me up” and “Seeing a movie won’t help me feel better”). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” with higher scores reflective of better regulation of negative moods. The test authors report strong internal consistency (≥.86 across samples).

Emerging adults self-reported their own emotion regulation on the NMRS and a parent-modified version asked parents to report on the items about their child’s emotion regulation ability. For the parent version, each item begins with “When my child is upset, I believe that…” followed by the possible reactions (e.g., for the sample items above, “Doing something nice for someone else cheers them up” and “Seeing a movie doesn’t help them feel better”). The current study obtained strong internal consistency for the emerging adult’s self-report (α = .90), comparable to that obtained for the maternal (α = .88) and paternal reports (α = .89).

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)

Depression and Anxiety subscales of the BSI (Derogatis 1983) were administered to assess distress level in the past month due to six dysphoria (e.g., low mood or worthlessness, such as “feeling blue”) and six anxiety (e.g., nervousness or shakiness, such as “feeling fearful”) symptoms, using a 5-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely.” Given the nature of data collection, the depression scale item assessing suicidal ideation was not administered. The 11 remaining items were summed to create a composite score indicating overall mental health functioning. Higher scores indicated greater mental health-related distress. Past work supports strong internal consistency (Cronbach alphas ranging from .82 to .88; Gameiro et al. 2013). In the current study, the 11-item total scale also evidenced strong reliability (α = .86).

Oregon Adolescent Depression Project-Conduct Disorder Screener (OADP-CDS)

The OADP-CDS (Lewinsohn et al. 2000) is a 7-item screener of delinquent behavior. Participants were presented with a range of deviant behaviors, from being caught lying to stealing, and endorsed or denied occurrence within the past 5 years. Sample items included, “I got into fights” and “I broke rules at school.” Items were summed to create a Total score, with higher scores reflecting higher frequency of delinquent behavior. Given the range of items, the authors expect somewhat lower internal consistency, reporting alpha at .76 in a large sample of late adolescent students. In the current sample, observed alpha indicated adequate internal consistency (α = .65).

Data Analyses

Statistics were initially conducted with SPSS 21 to obtain basic descriptive and correlational findings. We performed Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests to check the normal distribution of all variables; the only variables identified as potentially skewed were the child’s report of paternal Authoritative parenting history as well as the mental health and delinquency score totals; all of these were transformed, which reduced skew to nonsignificance. Aggregate scores for parenting style history were created by averaging the student’s report of a given parenting style history with the comparable report from their participating caregiver(s); if a parent score was unavailable, the aggregate score reflected the average of those scores that were available for that measure (i.e., two of the three reporters). After initial analyses, subsequent analyses involved latent-variable structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 21, obtaining maximum likelihood estimates of model coefficients. SEM can evaluate mediation models and provide fit indices that assess the measurement and structural components of a model simultaneously to determine the strength of the proposed model. Fit of the models was evaluated using Chi square of the proposed model, goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Byrne 2001; Tabachnick and Fidell 1996). The Chi square for the independence model, which tests the absence of relationship among the variables, should be significant (Tabachnick and Fidell 1996). With respect to the fit indices, GFI, CFI, and IFI values >.90 are ideal and RMSEA values are ideally .08 or below. Bootstrapped bias-corrected 90 % confidence intervals (based on 2000 samples) are also provided to evaluate the significance of indirect effects.

Results

Emerging adults demonstrated statistically significant moderate agreement (per Cohen’s standards) with their maternal caregiver and their paternal caregiver reports of parenting style history across the three parenting styles (see Table 1). Emerging adults reported strong consistency in parenting style between their two caregivers across the parenting styles (r’s = .61, .59, and .62 for authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting styles, respectively, all p ≤ .001), suggesting they perceive both caregivers as sharing similar parenting approaches. These results are stronger but comparable to the consistency of reported personal parenting style history between the two different caregivers (r = .38, p ≤ .001; r = .25, p ≤ .05; and r = .57, p ≤ .001, for authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting styles, respectively). Emerging adults did, however, report their mothers were significantly less authoritative (t = −6.14, p ≤ .001) and significantly more authoritarian (t = 5.37, p ≤ .001) than mothers themselves perceived (no significant differences on permissive parenting style history). Similar results were observed for emerging adults’ perspectives on their fathers, judging their history of paternal parenting to be less authoritative (t = −4.56, p ≤ .001) and more authoritarian (t = 4.14, p ≤ .001) than reported by their fathers (again, no significant difference on permissive parenting style history). Collectively, these findings support reasonable agreement across reporters, with no evident parental sex differences; thus, to streamline the presentation of parenting history for the purposes of reporting correlations, aggregate scores are presented in Table 2.

As seen in Table 2, the emerging adults also evidenced strong agreement with their maternal caregiver on their emotion regulation ability (by Cohen’s standards, a large effect) and moderate agreement with their paternal caregiver; both caregivers also tended to concur between themselves on the extent of their child’s emotion regulation ability (also evidencing a strong effect).

The next step was to consider whether parenting style history was associated with emotion regulation and whether emotion regulation was associated with mental health functioning and delinquency in order to consider emotion regulation as a potential mediator. As seen in Table 2, all reporters indicated that better emotion regulation abilities were significantly associated with more authoritative parenting history but authoritarian or permissive parenting history were not associated with any reports of the emerging adults’ emotion regulation. Emerging adults’ mental health functioning and delinquent behaviors were significantly correlated with each individual reporter’s assessment of the emerging adult’s emotion regulation ability (particularly mental health functioning; see Table 2). Neither mental health functioning nor delinquency behaviors were significantly associated with authoritarian or permissive parenting style history, contrary to the hypotheses. Given the pattern of these findings, SEM models concentrated on considering the observed significant associations with history of authoritative parenting (indeed, additional SEM models confirmed that neither authoritarian nor permissive parenting styles history predicted emotion regulation ability, mental health, or delinquency).

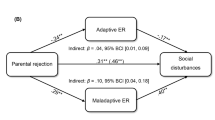

Confirmatory factor analyses indicated that scores from the four reporters of authoritative parenting significantly loaded on the underlying Authoritative Parenting History latent variable (maternal, paternal, and emerging adult report of maternal and parental authoritative, .43, .39, .85, and .66 respectively) and that scores from the three reporters of the emerging adults’ emotion regulation abilities significantly loaded on that latent variable (maternal, paternal and emerging adult report, .76, .53, .66, respectively). Initial SEM analyses indicated that Authoritative Parenting History significantly predicted mental health symptoms whereas authoritative history was not significantly directly linked to delinquency. Finally, evaluating the prediction of emotion regulation as a hypothesized mediator, SEM analyses were performed for authoritative parenting history with emerging adults’ reports of mental health functioning and delinquency as dependent variables. The best fitting model is depicted, with significant paths, in Fig. 1. This model obtained a significant χ2(23) = 31.67, p ≤ .001, with acceptable model fit indices, GFI = .94, CFI = .96, IFI = .96, and RMSEA = .06. The model suggests history of authoritative parenting directly predicted better mental health but emotion regulation also partially mediated the association between authoritative parenting history and emerging adults’ mental health functioning, with a significant indirect effect of −.48 (90 % CI −.31, −.25). Poorer emotion regulation only indirectly linked history of authoritative parenting and delinquent behavior, with an indirect effect of −.19 (90 % CI −.09, −.31).

Discussion

The current study sought to extend past research supporting a relation between parenting styles and potential child outcomes. Specifically, we examined whether emotion regulation ability of recently parented late adolescents explained their current mental health symptoms and delinquent behavior. Taking a multi-informant approach, both parents and their late adolescent child (18–20 years old) reported on parenting style history and the emerging adult’s emotion regulation ability. Additionally, emerging adults self-reported on their mental health functioning and delinquent behavior.

Results from SEM modeling provided partial support for the hypotheses. Emerging adults’ emotion regulation ability partially mediated the relation between history of authoritative parenting and self-reported mental health symptoms and indirectly predicted self-reported delinquency. Contrary to expectations, young adults’ emotion regulation ability was not related to their history of authoritarian or permissive parenting style. The current findings supported the use of multiple informants, with ratings on history of parenting style and emotion regulation skill converging across reporters.

The SEM analysis indicated that emerging adults’ emotion regulation ability partially explained the well-supported relation between authoritative parenting style and stronger mental health functioning, and better emotion regulation ability was linked with lower delinquent behavior. Thus, the current results underscore that authoritative parenting history could provide the context for the development of stronger emotion regulation ability that may serve to encourage better outcomes. Within a sample of relatively high functioning youth, emotion regulation may be an important byproduct of a history of more authoritative parenting that could translate to optimal functioning. Compared to other parenting styles, authoritative parents likely model adaptive emotional management (Chan et al. 2009; Morris et al. 2007). Current findings extend past work (e.g., Betts et al. 2009; Fischer et al. 2007) relating authoritative parenting style to fewer mental health and behavior problems by implicating emotion regulation skill as a possible mechanism that enhances functioning among emerging adults. Moreover, these findings demonstrate these relations based on an inclusive set of reporters on both parenting history and emotion regulation ability. Given that mental health functioning was more salient in this study compared to the more behavioral outcome of delinquency, additional work could consider different mediational mechanisms in how parenting style history influences problematic behaviors (e.g., peer relations, attachment).

Consistent with past research (e.g., Panetta et al. 2014), the present findings supported the hypothesis that a history of an authoritative approach is associated with fewer mental health symptoms. In contrast to expectations and some past literature, a history of more authoritarian or permissive parenting was not significantly related to emotion regulation or reported poorer mental health or delinquent behavior in this sample of emerging adults using a multi-informant approach. This finding is partly consistent with one study of adolescents that observed such an association of emotion regulation with authoritative parenting history but did not observe one with authoritarian parenting, although they did identify an association with permissive parenting (Jabeen et al. 2013).

The focus on emerging adult college students in this sample offers some possible explanations for the lack of significant findings for authoritarian and permissive parenting. First, traditional college students may represent a higher functioning population. Thus, the current youth may not reflect those emerging adults who have experienced significant psychosocial or economic barriers that would interfere with college attendance. Indeed, it would be particularly interesting to investigate, using a multi-informant approach, whether at-risk and clinical populations evidence emotion regulation as a mediator between parenting history and outcomes. Additionally, past evidence suggests males endorse delinquency at greater rates than females (Lewinsohn et al. 2000). The over-representation of females that occurred in the present sample may have contributed to lower endorsement of delinquent behavior. On average, the current sample reported modest mental distress, comparable to other estimates of psychological distress among college students (Constantine and Flores 2006; Masuda and Tully 2012); nationally, approximately 5 % of college students show poor mental health (Weitzman 2004). Arguably, those who endorsed symptoms of mental health or behavior problems may have developed strategies capable of compensating for such potential issues in order to enroll in college.

The lack of significant associations between potential outcomes and authoritarian and permissive parenting history may also partially relate to our dimensional conceptualization and measurement of parenting style. Consistent with movement away from a categorical approach of complex phenomena, participants’ ratings of historical parenting behavior allowed for degrees of each parenting style. Rather than artificially trichotomizing the sample based on the highest endorsed parenting style, a multidimensional conceptualization was taken supporting that one’s parenting history may feature authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive qualities. Existing evidence supports that displaying a degree of authoritative parenting may compensate for the presence of more authoritarian and permissive strategies and promote more positive outcomes than typically found when each style is examined in isolation (Watabe and Hibbard 2014). Given our findings, perhaps past experience of warm, supportive, and autonomy-respecting parenting creates resources that could offset displays of other parenting styles, a potential rich area for further inquiry. Moreover, our measurement of both parenting style history and emotion regulation was based on an inclusive multi-informant approach that has not been implemented in earlier research which has largely relied on single sources, potentially contributing to the differences in our findings relative to prior research conclusions.

The current findings underscore the utility of a multi-informant approach. Reports from emerging adults evidenced moderate agreement with parent’s self-reported parenting style, suggesting that such youth are capable of identifying and reporting on specific child-rearing approaches. Emerging adults’ reports indicated they perceive the delivery of each parenting style to be consistent between parents. Perhaps not unexpectedly, given differences in perspective and developmental stage, youth may generalize the parenting strategies from one, likely primary, caregiver to the other more secondary caregiver and attend less to potential style discrepancies that could be more apparent to parents’ themselves. Although overall reports evidenced significant overlap, some differing perspectives were apparent. For example, emerging adults described a greater degree of authoritarian parenting history from both parents than endorsed by their parents’ own reports. Instances of less warm, over-controlled parenting may be recalled as more distressing and thus salient to recently parented youth compared to their parents’ perceptions. Parents’ perspectives potentially capture the intention behind parenting strategies not reflected in youths’ reports. Similarly, parents’ separate perspectives evidenced somewhat greater disparity in style displayed by each parent as seen by the magnitude of the correlation, yet they still showed significant agreement, as observed in one of the few studies to include both parents (Rinaldi and Howe 2012). The overall findings are consistent with prior literature suggesting that the degree of agreement between reporters may vary, depending on the relation of the rating pairs (e.g., parent–child versus parent–parent) as well as the content being rated (e.g., internal versus external processes; van der Ende et al. 2012).

Reports on the emerging adults’ regulatory ability evidenced significant agreement across the three reporters, and was particularly strong in the mother–child dyad. Although not specifically predicted, higher correspondence between emerging adult and maternal reports may be expected given that the mothers, serving as the primary caregivers, likely have more exposure to potentially challenging child-rearing episodes wherein child regulatory ability could be observed. Moreover, daughter–mother dyads were over-represented in the sample given the larger proportion of female students participating. Considering women are often socialized toward more emotion expression (Barrett et al. 1998), mothers may have greater awareness of their children’s internal experiences and expression of emotion regulation such that they would be more familiar with their children’s emotion regulation ability.

Overall, reports from multiple informants allows for an examination of the degree to which personal perspective is distinct versus shared from others’ experience. Research on parenting continues to rely largely on parental report even when focused on child-related outcomes and despite evidence of children’s ability to self-report. The decision of how to manage and interpret multiple reports remains an important empirical question as outcomes and thus interpretations may differ based on the reporter. Relying on a single source for information not only provides a limited perspective but also suffers methodologically from source bias limitations. Continued consideration of how single versus multiple reporters influence research conclusions seems prudent, particularly in terms of re-evaluating earlier work regarding the potential outcomes for authoritarian and permissive parenting styles by adopting a multi-informant design with different samples.

With regard to additional study limitations, most salient is the cross-sectional approach of the current study and the need to pursue longitudinal designs; such a design could track the emergence of poor outcomes. In addition, alternative mediators and factors not measured in the current study may contribute to potential outcomes. Future work, for example, could consider the parents’ own emotion regulatory ability to help evaluate the potential role of parents’ skills in shaping their children’s skills. Parents’ report of youth’s mental health and delinquent behavior could also provide an alternate perspective, although youth were selected in this study as the more accurate reporters of such qualities. Mental health functioning was strongly associated with reported emotion regulation ability across reporters; although conceptually distinct qualities, future work should consider additional measures and dimensions of emotion regulation abilities to determine its association with mental health functioning, optimally using such multi-informant approaches. This study also relied on a measure often utilized with college students to assess parenting style history that does not include an assessment of neglectful parenting style history, an approach which is considered low in both parental control and warmth (Maccoby and Martin 1983). Future research should consider whether emotion regulation abilities are affected by a neglectful parenting approach as well. Moreover, a larger sample size would allow for more nuanced statistical analyses capable of determining whether the degree of authoritative parenting displayed by one parent may compensate for the application of authoritarian or permissive approaches of the other parent. Additionally, outcomes could differ when gender matched versus mixed dyads (e.g., son–mother) are examined, which would also require large samples. As noted above, the sample better represents mothers/daughters; thus, this sample may have over-represented mental health symptoms yet underrepresented delinquency issues. Future work with greater male representation could disentangle these issues. Larger sample sizes could also evaluate important potential covariates (e.g., race/ethnicity; gender-matched v. mixed dyads; SES; and other family compositions, including single-parent comparisons given that we did not have a sufficient representation of single-parent families in this sample to conduct analyses).

Overall, the current study sought to examine emotion regulation as a potential mediator between parenting style history and mental health and delinquency problems. The use of multiple informants of historical parenting style and youth’s emotion regulation skill supplemented individual self-reports. Correspondence versus subtle differences between reporters’ perspectives highlight the need for continued discussion of managing multi-informant data; little guidance is available in identifying whose perspective matters and in what contexts, suggesting that researchers continue to seek diverse and inclusive viewpoints. Based on the current sample, the promotion of authoritative parenting behavior could enhance developmental trajectories, but the impact of authoritarian and permissive parenting styles was less clear and requires further study with multi-informant designs. In addition, encouragement of youths’ emotion regulation skills specifically may defend against mental health and behavior problems. Continued investigation into such potential mechanisms is a promising avenue of research to help uncover how parenting approaches may shape outcomes for future generations.

References

Barrett, L. F., Robin, L., Pietromonaco, P. R., & Eyssell, K. M. (1998). Are women the “more emotional” sex? Evidence from emotional experiences in social context. Cognition and Emotion, 12, 555–578.

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37, 887–907.

Baumrind, D. (1972). An exploratory study of socialization effects on Black children: Some Black-White comparisons. Child Development, 43, 261–267.

Baumrind, D. (1971). Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 4, 1–103.

Betts, J., Gullone, E., & Allen, J. S. (2009). An examination of emotion regulation, temperament, and parenting style as potential predictors of adolescent depression risk status: A correlational study. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27, 473–485.

Bronte-Tinkew, J., Moore, K. A., & Carrano, J. (2006). The father–child relationship, parenting styles, and adolescent risk behaviors in intact families. Journal of Family Issues, 27, 850–881.

Buri, J. R. (1991). Parental Authority Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57, 110–119.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Casas, J. F., Weigel, S. M., Crick, N. R., Ostrov, J. M., Woods, K. E., Jansen Yeh, E. A., & Huddleston-Casas, C. A. (2006). Early parenting and children’s relational and physical aggression in the preschool and home contexts. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27, 209–227.

Catanzaro, S. J., & Mearns, J. (1990). Measuring generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation: Initial scale development and implications. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54, 546–563.

Chan, S., Bowes, J., & Wyver, S. (2009). Parenting style as a context for emotion socialization. Early Education and Development, 20, 631–656.

Constantine, M. G., & Flores, L. Y. (2006). Psychological distress, perceived family conflict, and career development in college students of color. Journal of Career Assessment, 14, 354–369.

Davidov, M., & Grusec, J. E. (2006). Untangling the links of parental responsiveness to distress and warmth to child outcomes. Child Development, 77, 44–58.

Derogatis, L. R., & Melisaratos, N. (1983). The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine, 13, 595–605.

Eisenberg, N., Zhou, Q., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Fabes, R. A., & Liew, J. (2005). Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development, 76, 1055–1071.

Fischer, J. L., Forthun, L. F., Pidcock, B. W., & Dowd, D. A. (2007). Parent relationships, emotion regulation, psychosocial maturity and college student alcohol use problems. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 912–926.

Gameiro, S., Canavarro, M. C., & Boivin, J. (2013). Patient centered care in infertility health care: Direct and indirect associations with wellbeing during treatment. Patient Education and Counseling, 93, 646–654.

Jabeen, F., Anis-ul-Haque, M., & Riaz, M. N. (2013). Parenting styles as predictors of emotion regulation among adolescents. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 28, 85–105.

Larzelere, R. E., Morris, A. S., & Harrist, A. W. (2013). Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, F., & Farrington, D. (2000). The OADP-CDS: A brief screener for adolescent conduct disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 888–895.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: Parent–child interaction. In P. H. Mussen & M. E. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 1–101)., Socialization, personality, and social development New York, NY: Wiley.

Manzeske, D. P., & Stright, A. D. (2009). Parenting styles and emotion regulation: The role of behavioral and psychological control during young adulthood. Journal of Adult Development, 16, 223–229.

Masuda, A., & Tully, E. C. (2012). The role of mindfulness and psychological flexibility in somatization, depression, anxiety, and general psychological distress in a non-clinical college sample. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 17, 66–71.

Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Journal of Social Development, 16, 361–388.

Panetta, S. M., Somers, C. L., Ceresnie, A. R., Hillman, S. B., & Partridge, R. T. (2014). Maternal and paternal parenting style patterns and adolescent emotional and behavioral outcomes. Marriage & Family Review, 50, 342–359.

Piko, B. F., & Balazs, M. A. (2012). Control or involvement? Relationship between authoritative parenting style and adolescent depressive symptomatology. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 21, 149–155.

Querido, J. G., Warner, T. D., & Eyberg, S. M. (2002). Parenting styles and child behavior in African American families of preschool children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 272–277.

Radziszewska, B., Richardson, J. L., Dent, C. W., & Flay, B. R. (1996). Parenting style and adolescent depressive, smoking, and academic achievement: Ethnic, gender, and SES differences. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 19, 289–305.

Reitman, D., Rhode, P. C., Hupp, S. D. A., & Altobellow, C. (2002). Development and validation of the Parental Authority Questionnaire—Revised. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 24, 119–127.

Rinaldi, C. M., & Howe, N. (2012). Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and associations with toddlers’ externalizing, internalizing, and adaptive behaviors. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27, 266–273.

Robinson, C. C., Mandleco, B., Olsen, S. F., & Hart, C. H. (1995). Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices: Development of a new measure. Psychological Reports, 77, 819–830.

Stright, A. D., & Yeo, K. L. (2014). Maternal parenting styles, school involvement, and children’s school achievement and conduct in Singapore. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106, 301–314.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (1996). Using multivariate statistics (3rd ed.). New York: Harper Collins.

Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of a definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59, 25–52.

Van der Ende, J., Verhulst, F. C., & Tiemeier, H. (2012). Agreement of informants on emotional and behavioral problems from childhood to adulthood. Psychological Assessment, 24, 293–300.

Walton, A., & Flouri, E. (2010). Contextual risk, maternal parenting and adolescent externalizing behaviour problems: The role of emotion regulation. Child: Care, Health, and Development, 36, 275–284.

Watabe, A., & Hibbard, D. R. (2014). The influence of authoritarian and authoritative parenting on children’s academic achievement motivation. A comparison between the United States and Japan. North American Journal of Psychology, 16, 359–382.

Weitzman, E. R. (2004). Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192, 269–277.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodriguez, C.M., Tucker, M.C. & Palmer, K. Emotion Regulation in Relation to Emerging Adults’ Mental Health and Delinquency: A Multi-informant Approach. J Child Fam Stud 25, 1916–1925 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0349-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0349-6