Abstract

This qualitative study examined caregivers’ perceptions of Parent Peer Support (PPS) services, embedded in the Wraparound service delivery model for youth with severe emotional and behavioral disturbances (SEBD), to identify potential engagement facilitators and barriers. Wraparound is a holistic process involving multiple formal and informal providers to collectively implement an individualized, family-centered plan of care focused on maintaining youth with SEBD within the community. PPS are frequently referred to caregivers involved in Wraparound to provide additional support. Caregivers (n = 35) previously involved in an evaluation of one state’s Wraparound model participated in a single 30–60-min interview. Interview questions examined caregivers’ expectations about PPS, reasons for accepting or refusing PPS, and caregivers’ perceived impact of PPS. Transcribed interviews were analyzed using strategies from grounded theory methodology. Perceived need, as well as desire for shared experiences, knowledge, and assistance in accessing resources, facilitated accepting the PPS service. Barriers included inaccurate expectations of PPS, time limitations on Wraparound services, escalating youth behavior requiring more restrictive placements, scheduling difficulties, perceived unresponsiveness, and caregivers feeling overwhelmed by the number of providers. Caregivers indicated that PPS provided several benefits for themselves, youth in the care, and their families. However, potential barriers to ongoing engagement included perceived intrusiveness, as well as misalignment between services offered and caregivers’ needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Caregivers rearing youth with severe emotional and behavioral difficulties (SEBD) often experience considerable personal strain (e.g., lack of personal time, anxiety, fatigue, sadness, guilt, disrupted family relationships), which has been linked to increasingly restrictive out-of-home placements for youth (Brannan and Heflinger 2006). In response, child-serving systems of care (e.g., behavioral health, special education, child welfare, juvenile justice) are investing in home and community-based service delivery models that can enable children with SEBD to remain at home (Mann 2013). Such models include among their service arrays Parent Peer Support (PPS), which are provided by caregivers who share the lived experience of caring for children with emotional and/or behavioral health difficulties. These providers are known as Parent Peer Support Partners (PPSP; also known as Family Advocates, Family Support Specialists, Parent Advocates, or Veteran Parents).

For the last 30 years, PPS in children’s mental health services have been provided to facilitate access to other services, increase meaningful family participation throughout the treatment process, as well as provide direct supports to caregivers of youth with emotional and/or behavioral health challenges (Hoagwood et al. 2010; Obrochta et al. 2011; Olin et al. 2014). PPS activities include, but are not limited to: outreach, system navigation, emotional support, assistance with action planning/priority setting, ensuring the prominent role of family voice in decision making, education, skill development, linkages to concrete services, facilitating engagement with service providers, collaboration with service teams, mediation between families and agencies to encourage collaboration, enhancing quality and quantity of social networks, as well as providing recreational and respite activities (Hoagwood and Burns 2014; Kutash et al. 2014; Olin et al. 2014; Wisdom et al. 2014).

While PPS has been associated with a number of benefits for caregivers and youth (e.g., Baum 2004; Hoagwood 2005; Hogan et al. 2002; Ireys et al. 2001; Konrad 2007; Koroloff et al. 1996; Kutash et al. 2011, 2013; Palit and Chatterjee 2006; Rhodes et al. 2008; Rodriguez et al. 2011; Ruffolo et al. 2005), there is limited research regarding the process through which caregivers engage in PPS when such services are embedded within larger service delivery models such as Wraparound, a prominent system-of-care service delivery model for youth with SEBD and their families. A greater understanding of this process may illuminate areas where Wraparound service quality can be enhanced to better promote engagement in PPS.

Since the term was first coined in the 1980s, “Wraparound” has been described variously as a philosophy, an approach, and a service (Van Den Berg et al. 2008). In recent years, Wraparound has been more consistently presented as an intensive, individualized care planning and management process for youth with SEBD. There are often substantial variations in Wraparound implementation, and adherence to core principles can vary greatly (Bruns 2015). Within the service systems described in this paper, Wraparound is intended to be a team-based process for coordinating care that incorporates multiple professionals and natural supports to address the numerous, complex needs of youth with SEBD and their families (Bruns et al. 2014). In jurisdictions which invest in the Wraparound service delivery model, multiple child-serving systems collectively serve youth with SEBD. “Care management entities” (CME) are utilized for building and managing comprehensive, intensive, and cost-effective Wraparound service arrays (including PPS; Pires 2013). CMEs are also responsible for training and hosting Wraparound staff, as well as ensuring low caseloads (e.g., 10:1), intensive service planning, cost management, and outcome monitoring (Pires 2013).

In order to build successful partnerships between family members and providers, the Wraparound process involves convening a team (known as the Child and Family Team [CFT]) of providers, relevant agency representatives, as well as natural and community supports (Miles et al. 2011). Over the course of 12–24 months, the CFT holds monthly face-to-face meetings to collectively review youth and family strengths, identify highest priority needs, develop and oversee implementation of individualized care plans, monitor progress, and revise care when needed (Miles et al. 2011; Walker 2008; Walker and Bruns 2006; see also http://nwi.pdx.edu/wraparound-basics/). Compared to other traditional service models, Wraparound involves a dedicated lead facilitator for each CFT (called the “Wraparound Care Coordinator”), follows a fixed set of Wraparound principles to ensure care plans prioritize youth and family preferences, utilizes the active involvement of natural helpers, emphasizes increasing social support, prioritizes attention to youth and family strengths, as well as uses flexible funding streams to meet unique family needs (Bruns et al. 2014; Suter and Bruns 2009). Wraparound care coordination emphasizes doing “whatever it takes” to transition youth back into the community, maintain them with family members, or keep them in the most home-like environment possible (Bruns 2008).

To achieve these overarching goals, typical Wraparound treatment targets focus on ensuring caregivers receive services to provide emotional support and understanding, ameliorate their stress, promote self-efficacy (in dealing with both complex systems as well as their child’s negative behaviors and emotions), and enhance their family’s social support network (Bruns 2008). An increasing subset of Wraparound-implementing systems refer families to PPS to address these treatment targets as well as ensure that the families’ perspectives are prioritized in decision-making (Osher and Penn 2008; Penn and Osher 2008; Walker and Schutte 2005). PPSPs are available to Wraparound-enrolled families through a range of partnership models (Miles 2008). In the dyad model, the Wraparound Care Coordinator and PPSP are paired as a team to implement the Wraparound process jointly with integrated responsibilities. In the coordinating partner model, the Wraparound Care Coordinator organizes the overall Wraparound process, within which the PPSP has distinct roles designed to support the parent. As a coordinating partner, the PPSP assesses the level of peer support that parents need and then engages parents accordingly; at minimum, the PPSP attends the CFT monthly meetings (Miles 2008). In the interventionist model, the PPSP is referred by the CFT to meet specific, time-limited needs.

Regardless of partnership model, PPS staff working in Wraparound can be housed within family support organizations, provider organizations, state agencies, CMEs, or health homes (Matarese and Harburger 2014). Thus, PPS may be available to families through agencies that directly provide Wraparound services or contracted out through the CME. PPSPs are typically viewed as important members of the Wraparound process, collaborating with families and professional service providers. Compared to other professionals, PPSPs are valued for their unique perspectives resulting from their personal “lived” experiences of caring for children with emotional/behavioral challenges (Penn and Osher 2008). PPSPs advocate for and support families, ensure families’ voices are heard by other providers, assist families to identify Wraparound team members, clarify terminology, brainstorm strategies for their plan of care, normalize caregivers’ feelings and experiences, assist in finding or developing natural supports, and connect families with community resources (see Penn and Osher 2008 for detailed examples). PPSPs may also be called upon to help stabilize crisis situations, define families’ concerns, identify families’ strengths, engage other team members, and assist with planning logistics (Osher and Penn 2008). Finally, PPSP activities are intended to be solely provided to caregivers, rather than directly to youths.

An important area to examine within PPS involves how caregivers engage in PPS services. Engagement involves the process through which child mental health difficulties are recognized, youth and families are connected to resources, families make initial contact with service providers, and families maintain participation in relevant services (McKay and Bannon 2004). This dynamic and ongoing process of engagement can be assessed via behavioral (e.g., attendance, homework completion), affective (e.g., emotional investment in and commitment to treatment), as well as cognitive (e.g., expectations, perceived relevance to needs) indicators of engagement (McKay and Bannon 2004; Staudt 2007). Staudt (2007) identifies many factors which can impact the quality of caregiver engagement (as assessed by behavioral, affective, and cognitive indicators), such as service relevance/acceptability, daily stresses, therapeutic alliance, external barriers to service utilization, and cognitions/beliefs about services. Ultimately, the quality of engagement impacts overall service effectiveness (Staudt 2007). To date, however, there has been limited empirical examination regarding caregiver perceptions of these processes specifically within the Wraparound service delivery model.

Existing research on PPS provided within Wraparound has focused on the Comprehensive Community Mental Health Services for Children and their Families (CMHI) program, in which families and youth with emotional and behavioral difficulties were served by 45 system of care communities from 1997–2004. Wraparound was among the many service delivery models utilized by grantees. Family educational and support services (including PPS) were provided to families enrolled in the CMHI program. Caregivers who accessed these services manifested higher levels of parenting strain and lower levels of family functioning compared to those who did not. Compared to caregivers not accessing PPS, those caregivers accessing PPS tended to have children with higher levels of emotional/behavioral difficulties, fewer strengths, and increased variety of mental health services (Gyamfi et al. 2010; Kutash et al. 2013). Moreover, 65% of those caregivers accessing PPS expressed satisfaction. However, no information was available on caregivers’ experiences of barriers and facilitators to utilizing PPS specifically. Moreover, as different service delivery models were utilized, it is not possible to distinguish those focused on Wraparound specifically, or those programs which utilized PPS exclusively vs. also utilizing clinician-led family education and support services. Other research on PPS within Wraparound has documented that referrals to PPS often do not successfully occur (Bruns et al. 2014). Furthermore, a lack of clarity about PPSP roles has often been reported in Wraparound team meetings (Walker and Schutte 2005), suggesting that caregivers could be misinformed about PPS when being referred.

Based on literature from other service delivery models outside of Wraparound, various factors may impact the ability of caregivers to engage with PPS. For example, Slowik et al. (2004) reported that recruitment to a parent peer support group within an inpatient hospital setting faltered until research staff obtained buy-in from nursing staff who referred families to the group. Olin et al. (2015) examined the relationship between caregivers’ levels of depression, anger expression, and working alliance with PPSPs embedded within home and community-based waiver programs in New York State. Among those caregivers who were not clinically depressed, working alliance with PPSPs was negatively impacted by caregiver anger expression, suggesting that PPSPs should be trained specifically on addressing parental anger to improve working alliance among non-depressed parents. Research on PPS provided as part of statewide peer-to-peer support organizations (Adams et al. 2006) and parent-to-parent programs for children with disabilities (Santelli et al. 1995) underscore the importance of PPSPs contacting caregivers in a timely manner, as well as providing services relevant to caregivers’ needs. There is some indication that PPSPs have had more difficulties engaging ethnic minorities compared to Caucasian parents, particularly when PPSPs are not minorities themselves (Santelli et al. 1995). It should also not be assumed that all caregivers would welcome PPS into their lives. While many caregivers have reported confidence in PPSPs (Konrad 2007), some parents may be concerned about having to share painful information among peers or feel they already have enough services (Slowik et al. 2004).

Consequently, the current study intended to expand the knowledge base on pertinent factors impacting caregiver engagement into PPS. Specifically, we focused on caregivers’ experiences of PPS delivered within one state’s Wraparound initiative. In this paper, we addressed the following research questions: (1) What were caregivers’ expectations for PPS? (2) What were caregivers’ reasons for accepting or refusing PPS? (3) What were caregivers’ perceptions of PPS impact on themselves, youth receiving Wraparound, and their families?

Method

This study was conducted in a low-income, urban setting in Maryland where Wraparound was provided as part of a state initiative entitled “Maryland Crisis and At Risk for Escalation diversion Services for Children” (MD CARES). This initiative focused on the care management and treatment of youth in the foster care system at the point of initial diagnosis of SEBD, and who were at-risk of out-of-home placement or disruption of placement. Youth and their families initially enrolled in Wraparound services through CMEs and were assigned a Wraparound Care Coordinator upon enrollment. Wraparound Care Coordinators were responsible for subsequently referring all families enrolled in MD CARES to PPS, under the coordinating partner model. PPSPs were housed in a separate family support organization, and contracted out to work with families enrolled in MD CARES. The current study is embedded within a larger longitudinal evaluation of the MD CARES initiative. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study.

Participants

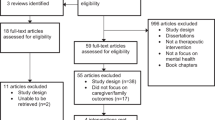

Purposive sampling methods identified participants who met a specific set of criteria: Caregivers were eligible to participate in the current study if they were 18 years or older, English speaking, and were caregivers to youth who were previously consented to participate in the longitudinal evaluation of MD CARES from 1 January 2012 through 31 December 2013 (n = 66). This specific time frame was chosen to limit the risk that caregivers would be unable to remember their experiences with PPS. Evaluation staff from MD CARES contacted potential participants multiple times by telephone and letter to inform them about the current study. Of n = 66 potential participants, n = 18 could not be reached by phone or mail, n = 8 refused, n = 5 were contacted but never scheduled (e.g., did not return voicemail messages), and n = 35 agreed to meet with research staff in private locations to review research materials. Between 1 June 2014–31 August 2014, a total of n = 35 caregivers (53% of eligible caregivers) provided written consent to participate in the current study. Consent from only one caregiver was obtained when there was more than one adult residing in the home (n = 23, 77%).

Table 1 presents demographic information about study participants and youth in their care. As indicated in Table 1, 40% (n = 14) of youth who initially received Wraparound did not live with their caregiver at the time of the interview. Of these youths, 21% (n = 3) were reported as living with a relative (grandparent or other relative), another 21% (n = 3) living with a foster parent, and 37% (n = 5) living with child welfare staff (e.g., group home). Of the 35 participants in this study, 80% (n = 28) no longer received Wraparound services at the time of the interview, 9% (n = 3) were still enrolled in Wraparound services, and 11% (n = 4) of participants were unaware if their child currently received Wraparound services. Most participants (n = 29, 83%) indicated they were informed about PPS from their Wraparound Care Coordinator, Department of Social Services worker, or youth therapists. Consequently, findings are based on responses for these caregivers, as those who indicated they were not informed (n = 6, 17%), were unable to provide further information related to this study’s research questions.

Procedures

All caregivers were interviewed by a single study interviewer (TL), who had prior experience as a research team member for the MD CARES longitudinal evaluation. The study interviewer received didactic and experiential training on interviewing techniques from the first author (GG). As part of training, the interviewer was instructed to ask qualitative questions from the semi-structured interview guide (see Measures section for more information), as well as prompt participants for greater details or clarity (e.g., “tell me more”). All interviews took place in participants’ homes between 1 June 2014–31 August 2014. Interviews lasted 30–60 min and participants received $20 for their participation. Participants’ responses were audio-recorded to assist in data collection and analyses. Audio files were checked for accuracy of interviewing techniques, and transcribed verbatim. Finally, all written transcripts were reviewed for accuracy against audio recordings.

Measures

Participants took part in a single interview consisting of close-ended questions gathering information on participant demographics, and semi-structured open-ended questions eliciting caregivers’ perspectives of PPS provided through the Wraparound service delivery model. The interview guide included questions about how caregivers were informed about PPS and their related expectations (e.g., “What were your expectations about PPS”), reasons for accepting or refusing PPS (e.g., “What were your reasons for accepting/NOT accepting PPS”), and their perceived impact of PPS on themselves, youth participating in Wraparound, and their families (e.g., “How did your experiences with PPSP affect you?”).

Data Analyses

Demographic data were analyzed via descriptive statistical methods (e.g., means, SD, percentages). Qualitative data analysis incorporated strategies from grounded theory methodology (Glaser 1965; Strauss and Corbin 1998), including open (i.e., identifying categories along with their properties and dimensions) and axial coding (i.e., relating categories to their subcomponents), constant comparative analysis (i.e., examining for similarities and differences across all data), and saturation (i.e., when no further themes appear). This study deviated from traditional grounded theory methods as we recruited a criterion-based purposive sample (using established inclusion and exclusion criteria at study onset) rather than sampling theoretically (i.e., choosing new criteria to sample for additional cases in order to expand upon theoretical constructs; Creswell 2007). A sample size of 35 is appropriate for a grounded theory approach, as saturation can usually be obtained with smaller samples (Morse 2000). An initial codebook was developed from a priori (based on interview questions) and emergent categories (from Open Coding). Sections of transcript text were coded by primary and secondary coders (MP, SM). Discrepancies were discussed with the research team, codebook definitions further refined, and subcomponents of codes identified (i.e., Axial coding). This process was repeated until research staff concluded that no further themes emerged (i.e., saturation) and initial interrater reliability ((# of agreements/ (total number of agreements + discrepancies)); Miles and Huberman 1994) was at least 90% across all codes. All transcripts were subsequently divided between two coders to code independently, with 25% of transcripts (n = 9) randomly selected to be double coded (coded by both coders) in order to compute the final interrater reliability (93%).

We utilized Atlas.ti (version 7) to code transcripts. Coded segments of all transcripts were reviewed by research staff using constant comparative analyses to identify similarities and differences among participant responses. The use of multiple members of the research team to independently review coded segments of the transcripts mitigated against individual researcher bias and selective perception, thus increasing validity of findings through researcher triangulation (Patton 1999). Participant responses were subsequently summarized into themes, using relevant transcript quotations as exemplars. Descriptive data (n, %) was computed to examine the prevalence of themes endorsed by participants. To further ensure validity of findings through member checking (Lincoln and Guba 1985), the current study’s results were reviewed and corroborated by a caregiver who received PPS and who is also a PPSP.

Results

Of the n = 35 participants interviewed, n = 29 reported ever being informed about PPS, n = 27 accepted PPS, and n = 23 received PPS. Findings are organized around themes emerging from analyses, which corresponded closely to the research questions for the study: (1) Expectations about PPSP, (2) Reasons for accepting or refusing PPS, and (3) Perception of PPS impact. Table 2 presents the quantitative distribution of themes and their characteristics to demonstrate the prevalence of themes within this sample.

Expectations About PPSP

Caregivers based their expectations of PPS on their family needs and the explanation they received regarding the role of the PPSPs from the referral source (e.g., Wraparound Care Coordinator, therapist). Many had expectations of being informed about and connected to resources such as basic needs, finances, housing, transportation, and employment. In addition, caregivers also expected referrals for youth in their care to receive a mentor or participate in activities outside the home (e.g., camp, recreation center). As examples, caregivers responded below when asked about their expectations from PPS:

“That I would actually receive services that would help me provide um, rent for children, help me provide better food for my children, Christmas for my children.”

“Um, support services for us, like um, counseling, um, financial um, um, financial counseling, ‘cause I needed that at the time.”

“I expected um, services. More, I guess, I was looking more so, for out of the home services, you know what I mean, when you have special needs children, and the children are in the home, because of their disabilities and because it does enable them to be in the communities. Without a um, a guardian or professional supervision….Going out to dinner, um, going to the movies, going to the mall.”

Some caregivers had expectations of receiving direct support from the PPSP such as someone to talk to, help during a crisis, and respite (e.g., short-term accommodation of youth to provide temporary relief to caregivers). Below are exemplars when caregivers were asked about their expectations:

“I needed, you know, just a contact person if [YOUTH] was in crisis. And if I needed to talk to someone that was like, a like parent, people, people like me.”

“..give me just, even if it was just a two hour break, so I could just take a nap …”

When asked about their expectations for PPS, some participants also expected that PPSPs would provide direct support by helping to improve parenting skills:

“Well, to learn a little more about being a single dad, or parent. …By, you know, on my own, me and my wife is separated, we been separated over 10 years. And uh, just being doing it by myself. …With my only son, he’s my only son. You know, and uh, I was, I was raised by a single mom, so I didn’t have a dad…. So, you know, I needed some, some guidance in, in helping and doing things with him.”

“Uh, just to see if somebody can help me get this girl together. [laughs] Basically to see if I could, because everybody, you know, views and points are when they come to raising teenage girls.”

Many caregivers also expected that PPSPs would provide direct support to youth, including counseling and recreation, as exemplified in the exemplars below:

“I just wanted to see how she would feel with talking to different people. Maybe, you know, get some of the anger out.”

“Uh, as far as education uh, giving them, you know, uh, entertainment, things to do to keep ‘em out of trouble. Stuff like that.”

Reasons for Accepting or Refusing PPS

Of those informed about PPS, the majority of caregivers chose to work with a PPSP when offered. When asked about their reasons for accepting PPS, caregivers’ needs led them to seek additional support with accessing resources, navigating existing services, having someone to talk to with a shared experience, as well as receiving guidance around parenting. For example, participants indicated:

“I just felt it was important for me, to um, be able to discuss some of the issues, that I was dealing with, and just having a break away to…. being with someone that understood”.

“I think any support services for those who are caregivers, would only enhance the relationship between me as a caregiver and [YOUTH] and being able to help her as well… understand a little better, some of the things that she goes through”.

Alternately, caregivers accepted PPSP based on youth needs for additional resources (e.g., referral for mentoring), as well as direct interaction with youth, as exemplified below:

“She [YOUTH] really didn’t have a lot of friends. She had trouble with some of her relationships in school, there weren’t any kids in the neighborhood to play with… I definitely thought… some type of a peer mentor may be a good support system for her, another person her age to, you know, make a connection with. Or learn, develop her communication, social skills that type of thing.”

“[I needed] Different other programs in reference to my son. Tutoring.”

A few families never received services even though accepting PPS. Reasons for not receiving PPS included the youth being admitted to inpatient services, as well as Wraparound services being near completion at the time of referral. A few participants had scheduling conflicts or indicated a lack of responsiveness by the PPSP, as exemplified below:

“No show. No call, no nothing. Called back the third time. And I asked ‘em what happened. I told them this is the second time that y’all had did this to me. I said I don’t wanna keep going through this. Either you’re going to help me, or you’re not going to help me.”

Finally, a couple of participants refused PPS when offered. One caregiver indicated that the youth in her care was removed from the home before she could officially accept PPS, while another refused PPS when initially offered, indicating that an additional provider would have been too overwhelming:

“Um, [the reason for rejecting PPS was] because she was already with uh, Wraparound, um, she had a lot going on right then and there. So, probably two agencies would have been too much for her, I think.”

Perception of PPS Impact

The following section discusses participants’ perceived impact of PPS, subdivided for caregivers, youth, and the overall family.

Caregivers

Overall, the majority of participants reported benefits for themselves, youth in their care, and their families as a result of their experiences with PPSPs. Most commonly, caregivers reported that PPSPs provided emotional support (e.g., building a support system, creating friendships, being comforted), as well as linkages to concrete services (e.g., mentor for youth, transportation, employment leads, mental health services). Below are some examples of quotes from participants:

“I mean, he was, he was there when we called him. You know, if we ever needed him, and everything. He was, you know, he would come out and um, would talk with us and um, I mean, we, we had no problem with communication anything like that. So, I think he was pretty supportive.”

“Um, he gave me some job leads that he knew about. And I was able to get employment…. So, he gave me resources to that. He also helped me get to the resources with me to appointments…. Oh, he gave me a referral for a therapist. Oh, he told me about, you know, different programs that the [FAMILY HEALTH PROGRAM] had. Um, he told me about different places I can go to get things to fix my house uh, um, different resources and grants that I qualify for.”

A number of caregivers indicated that PPS provided them with information about resources and service systems. For example, one caregiver stated the following:

“Um, another thing that I have to say that I’m really big, having to thank you for [PPSP] was um, she assisted with me coordinating a meeting with my sister’s IEP team at her previous middle school. Um, she gave a lot of background information about stuff that I wouldn’t have known about… So, that was extremely beneficial.”

Caregivers also indicated that PPS helped increase their understanding of youth in their care through information on child development and parenting skills, as exemplified below:

“Well, he um, he gave me a few options of what could be done like… if I asked [YOUTH] to do something, and um, I’ll give him a 15-min grace period to get it done, if it’s not done, then come check on him, and you know, reinforce what I was asking him to do. He also said maybe um, once he hasn’t done it the second time he was asked, instead of just asking him to do it, then both of us can just go together and get it done.”

Caregivers also reported that PPSPs were instrumental in relieving overall stress. For some, the very act of providing support relieved stress for some caregivers. A few caregivers indicated that their enhanced caregiving skills facilitated through PPS resulted in reduced youth behavioral difficulties, which then ultimately helped to the reduce their stress. Some examples are provided below:

“Um, well, it took off a lot, like I said, it did relieve a lot of stress and it took a, you know, a lot of the burden from us as far as um, you know, trying to find things to do with him, as far as you know, where are occupied or pre-occupied with things.”

“Well. Um, like I said it, it, it made me feel like I wasn’t alone with dealing with this issue with [YOUTH]. You know, if I had a issue, where I have addressed with [YOUTH] on numerous occasions, and gotten no results at all, I knew that I could call one of them and have them, you know, maybe get him a fresh conversation on what needs to be done and you know, maybe put a little twist to what I might have said.”

However, some caregivers reported negative experiences from their participation with PPS. In some cases, caregivers indicated PPS were ineffective, while others revealed that PPSPs did not address what was most relevant to caregivers. Examples of these perceptions are provided in the following exemplars:

“They would, this was the craziest thing, they would ask him, like oh, do you like sports, well we’re gonna try to get you into this and try to get you into that. We were there for like a year, and never got him into anything, because they didn’t know anything about the community.”

“What I said to them, what I actually needed, that’s when the meetings kept coming up, well, we have to have a meeting and get everyone involved and see if that’s something that he actually needs. It wasn’t a, a choice of like, I can tell you what is needed. They tell you what you need and that’s just not acceptable.”

Caregivers also felt there was a lack of responsiveness by the PPSPs, as exemplified here:

“They never came through with any of the stuff that I asked for, and requested and needed help with. They never came through with the help for my rent, they didn’t come through with the help for my food. They didn’t come through with the help for my Christmas. Um, they did not help me come up with a break. Nothing. They called me that one time, said that they were gonna schedule an appointment to come to my house. We had a date set up for December the, the something. Can’t remember, I just know it was in December. And since I wasn’t working, I scheduled the appointment for nine in the morning. I was up at eight o’clock in the morning. House all straight and tidy, sitting in the living room, waiting for them to knock on the door, they never showed up.”

The two exemplars below document how the perceived ineffectiveness combined with caregivers’ feeling overwhelmed with more service providers in their home led to caregivers feeling stressed:

“So, because every time they came, it was like okay, well this the meeting and this is what we said last time and this is what we said we were gonna do this time, which what we said we were gonna do was really nothing. So, it was just kinda bothering me and then she would stop out, like, she would tell me when she was coming, but then, she would stop by and just like, oh, I was in the neighborhood. Oh, so you just happened to be driving through [STREET]? And dropped through, oh, okay. [laughs] It was like kinda having a social worker at my [INAUDIBLE] 24/7, I’m like no, I’m not opening that door. I know she’s out there. I’m not doing it! Nope. [laughs] … It stressed me out just even knowing that they were coming, so it was more tense in the house than not. It’s like oh, god, they’re coming.”

“It was more time consuming than actually getting anything done. We always wan-, they always wanted to have meeting after meeting, after meeting, after meeting and we weren’t getting anything accomplished….Too many meetings and, you know, I could see if um, we were having meetings and there were things that were being done, but they weren’t being done.”

Youth

According to some caregivers, PPSPs directly interacted with youth, through mentoring, role modeling, taking youth out for activities, individualized counseling, as well as connecting youth to additional services and concrete resources As a result, these caregivers indicated that youth benefited from their involvement with PPSPs, as indicated by improved coping skills, increased confidence, expanded social networks and social involvement, reduced emotional and behavioral difficulties, as well as improved academic performance. Examples of caregivers’ perception of PPS benefit for youth are provided below:

“[PPSP] Gave her a better attitude as far as respecting herself, and adults…. it’s a lot calmer…. she learned how to go write in her book when she upset, she know how to, you know, sec-seclude herself, you know, or even if her, even it’s just her sister or her brother getting her upset…. because [YOUTH] deal with her anger better. She know how to ignore her sister now.”

“I think that it gave him some positive enforcement, which, you know, helped him think things out a little more. And you know, like I said, I did see small little changes in him, his eagerness to go to school, and you know, to actually work towards something.”

One caregiver indicated that youth behavioral difficulties were reduced as a result of her improved parenting skills developed with the PPSP:

“Well, it probably affect good, because you know, if I try whatever she told me on her, you know, to be kinda, you know, like patient and you know, and, you know, kinda stick to my guns no matter what… it worked, you know”.

However, a few caregivers reported that youth also had negative experiences with PPSP, as indicated when caregivers reported that youth were dissatisfied with PPS activities, or disliked interactions with PPSPs:

He was just kinda, especially with him having ADHD, he just didn’t want to uh, sit still long enough to go through meeting after meeting after meeting. He just was not interested. Because it was too time consuming for him. And it wasn’t something that he enjoyed.

Um, he didn’t want them here either. Like, he’d be like, just like, he, every, every time they were supposed to, oh god, they’re coming again, today, for what?! He would say what I’m saying.

Families

Caregivers also indicated that the family as a whole benefited from PPS, such as improved family communication and dynamics quality, and reduced family stress and conflict, as exemplified below:

“Well, I feel like they helped me, us, get to know each other a little bit better. Because you know, uh, she shared some things that she admired me about, I never really saw them as strengths.”

“it’s, it’s less stress and tension the house… A whole lot less from when we first, it was ahhhh, you know, it don’t be too much, you know, every now and then, you know, but no, not before, it’s a lot calmer.”

“Everybody was on the same page, it was a open di-, uh, conversation. Dialogue. Everybody contribute. And every-, and everybody goal was to support [YOUTH]….. So, it was just a, a united front for him.”

Discussion

The current qualitative study explored the perceptions of caregivers receiving PPS through Wraparound in one state. Major themes focused around caregivers’ expectations for PPS, reasons for accepting or refusing PPS, and perceptions of PPS impact. Importantly, the current study identified a number of factors that can facilitate and/or hinder caregiver engagement in PPS within Wraparound.

Generally speaking, caregiver expectations for PPS reflected the roles previously identified within the Wraparound literature, except for the expectation of direct services for youth. One potential explanation for this may involve misinformation or lack of clarity around PPS roles when referred by Wraparound Care Coordinators. Indeed, Walker and Schutte (2005) reported there was often a lack of clarity around the role of the PPSPs in Wraparound team meetings. Insufficient understanding of the role or value of PPSPs within the larger service organization has been commonly reported, and often hinders the ability for PPSPs to adhere to family support practice guidelines or provide high quality parent peer services (Olin et al. 2014). However, as this study focuses on caregiver experiences and reports only, we are unable to confirm whether Wraparound Care Coordinators actually discussed PPS with caregivers prior to referral and what they specifically told caregivers.

Regardless, greater clarity around PPS roles and activities for caregivers is needed based on findings from this study, as inaccurate expectations for service delivery can hinder future service engagement (McKay et al. 1996). Practice recommendations specific to these findings may include concretizing the roles of PPSPs within their host agencies and each Wraparound team, utilizing existing online resources as models (e.g., http://www.fredla.org/parent-to-parent-support-resources/). In addition, marketing tools (e.g., brochures, DVD) may help to clarify PPS roles for caregivers. Training for Wraparound care coordinators and other members of CFTs may also be needed to ensure accurate perceptions of PPS roles and value, in addition to elucidating the processes for referrals to PPS during the early stages of Wraparound.

Findings regarding why caregivers accepted or refused PPS identified a number of engagement facilitators (e.g., perceived need, desire for shared experiences, wanting greater knowledge and assistance in accessing resources), as well as specific barriers (e.g., scheduling conflicts, lack of responsiveness) that may be modifiable in practice. Notably, one caregiver refused PPS once offered due to feeling overwhelmed by too many professionals being involved. This highlights the perception that many may have when receiving services from multiple providers (as often occurs within the Wraparound service delivery model), with some research demonstrating that teams with too many members are associated with lower Wraparound implementation fidelity (Munsell et al. 2011). Considering strategies from evidence-based interventions promoting engagement in child mental health treatment (McKay et al. 1996), providers may want to proactively address this potential barrier with caregivers prior to referral to PPS by asking about such concerns. This may provide an opportunity to resolve any potential misperceptions and problem-solve around common challenges for caregivers involved with multiple providers (e.g., conflicting demands on caregiver time and energy; Kemp et al. 2009).

Results from the current study also indicate that caregivers perceived a number of benefits for themselves, youth in their care, and their families as a result of PPS. Such findings are consistent with prior research reporting outcomes associated with PPS (e.g., Baum 2004; Hoagwood 2005; Ireys et al. 2001; Konrad 2007; Koroloff et al. 1996; Kutash et al. 2011, 2013; Palit and Chatterjee 2006; Rodriguez et al. 2011; Ruffolo et al. 2005), and underscore the value of providing PPS within Wraparound services. That said, the “negative experience” exemplars document a more nuanced perception of PPS. One caregiver indicated that the presence of the PPSP felt like a social worker monitoring her family. Inherent in this comment is the perception of an unequal power differential between the client and PPSP, similar to what is often experienced between wary parents and child welfare professionals who have authority to remove children from their home or delay their return (Stephens et al. In Press).

This contrasts with prior research, which has found that caregivers feel more comfortable sharing personal information with peers as opposed to formal treatment providers, because of the shared experience of parenting children with behavioral difficulties (Gopalan et al. 2014). At some point for the caregiver in this study, the PPSP came to be perceived less as a peer who could understand her experiences, and more as a punishing and powerful professional. This highlights the potential for PPSPs to lose their “peer” benefits in the eyes of caregivers, although does not clarify how this occurred. In terms of practice recommendations, such findings suggest that PPSPs may need to tread cautiously in their attempts to engage families lest they become perceived as intrusive, particularly for those families with a history of contentious and negative experiences with service providers (Kemp et al. 2009).

The “negative experience” exemplars also pointed to situations where the resources offered by PPSPs were not aligned with caregivers’ immediate needs. Since the current study examined caregiver perceptions only, it is unclear if such experiences resulted from an inability of PPSPs to follow through on Wraparound principles that prioritize family voice and choice, or miscommunication between caregivers and providers. However, current findings underscore the importance of focusing on caregivers’ immediate, concrete needs as an engagement strategy that demonstrates providers’ commitment and potential to provide help (McKay et al. 1996). Although ongoing assessment of families’ needs remain important, establishing the initial rapport and trust with families requires evidence that providers are helpful with more immediate requests, even if they may be outside the scope of service. Once this can be established, caregivers are more likely to engage in longer-term activities.

Another interesting finding involves caregivers’ reports that PPSPs intervened directly with youth, although this is technically outside the PPS scope of services. One possible explanation could be that PPSPs with a more holistic approach felt that direct intervention with the child/youth participating in Wraparound ultimately provided support to caregivers, either through child care relief, as well as through improved youth behavior that reduced caregivers’ stress. Indeed, many caregivers in this study reported their stress reduced due to respite provided when PPSPs worked directly with youth. As caregivers request that someone work directly with youth to relieve their own caregiving stress, PPSPs may also be increasingly pulled toward directly intervening with youth.

This brings to question whether PPS should be limited in its scope of practice to only supporting caregivers, or if direct intervention with youth should be considered as an additional practice focus that ultimately helps caregivers. On the one hand, expanding PPS scope of practice to include direct services to youth may improve overall service quality and effectiveness. However, the addition of such responsibilities may impede on PPSPs ability to provide support for caregivers. Moreover, there may be opposition on philosophical grounds due to concerns that caregivers’ needs may be under-prioritized. Alternately, youth peer advocates (young adults with prior lived experience of having emotional/behavioral difficulties and receiving mental health services; Gopalan et al. 2017) may also be utilized during the Wraparound process to address direct services to youth, working in conjunction with PPSPs. An additional complication, however, lies with the specific Medicaid billing language for peers within states. Currently, Medicaid billing guidelines require precise differentiation between types of peers that can be billed, otherwise jurisdictions may only be able to bill for one type of peer provider. Readers are referred to the National Technical Assistant Network for Children’s Behavioral Health (tanetwork@ssw.umaryland.edu), which can provide guidance to policymakers on establishing appropriate policy language for Medicaid billing.

There are limitations of this study worth mentioning. Findings are limited to those caregivers we were able to locate and consent into the current study. There may be the possibility that the experiences of caregivers we were unable to locate differed from those we interviewed. We also limited the sample of caregivers from which we drew our participants to a specific time frame in order to mitigate against the risk of memory loss and biased responses. That said, caregivers might have had difficulty remembering retrospective experiences with PPS. Moreover, data from this study are drawn from a single state implementing Wraparound, and may not be generalizable to other geographic locations, as different processes may exist within the Wraparound service delivery models across the country. The sample-specific demographic composition of the current sample (e.g., 91% of caregivers identifying Black or African American, the mean age of youth (16 years), and 40% not living with caregivers at the time of the interview) also potentially limits the generalizability of findings for caregivers’ experiences of PPS across the country as well as for those families with younger children. Close to half of the sample (45%) reported annual incomes of less than $20,000, also suggesting high rates of poverty within this sample. It is possible that the common stressors of families impacted by poverty (e.g., community violence, unstable housing, prior negative experiences with service providers; McKay and Bannon 2004) may have influenced findings, potentially leading to more “negative experiences” with PPSPs. Additionally, the developmental needs of teenagers may have also influenced caregivers’ expectations and desire for mentoring and activities that are specifically relevant to adolescents. Finally, with close to half of the youth not residing with caregivers at the time of the interview, it is possible that more negative experiences with PPSPs were elicited than what might occur if more youth were able to be maintained in the home by the time of interview.

Despite these limitations, however, findings from the current study add to the literature on PPSPs by providing rich description of caregivers’ experiences through the engagement process. For future research, it will also be worth exploring similar perspectives of PPSPs, as well as those of Wraparound Care Coordinators. Additional future research questions may focus on differences in caregiver, youth, and family outcomes when PPSPs work solely with caregivers compared to working with youth directly as well. Finally, future research may build upon the current study by continuing to examine the mechanisms through which PPS impacts youth. A focus on youth outcomes is particularly salient as PPS may augment the effect of services, like Wraparound, designed to address youth emotional and behavioral challenges. Identifying the various ways through which youth are impacted by PPS will provide justification for funding such services within the child mental health system, particularly if involvement with PPS can mitigate against the risk that youth with SEBD enter into costlier treatment services, such as residential or hospital placements.

References

Adams, J., Westmoreland, E., Edwards, C., & Adams, S. (2006). The “keys for networking”: Targeted parent assistance. Focal Point, 20(1), 15–18.

Baum, L. S. (2004). Internet parent support groups for primary caregivers of a child with special health care needs. Pediatric Nursing, 30(5), 381–401.

Brannan, A. M., & Heflinger, C. A. (2006). Caregiver, child, family, and service system contributors to caregiver strain in two child mental health service systems. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 33(4), 408–422.

Bruns, E. (2008). Measuring wraparound fidelity. In E. J. Bruns & J. S. Walker (Eds.), The resource guide to wraparound (Chapter 5e.1). Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative, Research and Training Center for Family Support and Children’s Mental Health.

Bruns, E. J., Pullmann, M. D., Sather, A., Brinson, R. D., & Ramey, M. (2014). Effectiveness of wraparound versus case management for children and adolescents: Results of a randomized study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(3), 309–322.

Bruns, E. (2015). Wraparound is worth doing well: An evidence-based statement. In E. J. Bruns, J. S. Walker (Eds.). The resource guide to wraparound. Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative. Chapter 5e.4.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445.

Gopalan, G., Acri, M., Lalayants, M., Einbinder, E., & Hooley, C. H. (2014). Child-welfare involved caregiver perceptions of family support. Journal of Family Strengths, 14(1), 1–25. Article 5.

Gopalan, G., Lee, S.J., Harris, R., Acri, M., & Munson, M.R. (2017). Utilization of peers in services for youth with emotional and behavioral challenges: A scoping review. Journal of Adolescence, 55, 88–115.

Gyamfi, P., Walrath, C., Burns, B. J., Stephens, R. L., Geng, Y., & Stambaugh, L. (2010). Family education and support services in systems of care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 18(1), 14–26.

Hoagwood, K. E. (2005). Family-based services in children’s mental health: A research review and synthesis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46(7), 690–713.

Hoagwood, K. E., & Burns, B. J. (2014). Vectoring for true north: Building a research base on family support. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 41(1), 1–6.

Hoagwood, K. E., Cavaleri, M. A., Olin, S. S., Burns, B. J., Slaton, E., Gruttadaro, D., & Hughes, R. (2010). Family support in children’s mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–45.

Hogan, B. E., Linden, W., & Najaran, B. (2002). Social support interventions: Do they work? Clinical Psychology Review, 22(3), 381–440.

Ireys, H. T., Chernoff, R., Stein, R. E. K., DeVet, K. A., & Silver, E. J. (2001). Outcomes of community-based family-to-family support: Lessons learned from a decade of randomized trials. Children’s Services: Social Policy, Research, and Practice, 4(4), 203–216.

Kemp, S. P., Marcenko, M. O., Hoagwood, K., & Vesneski, W. (2009). Engaging parents in child welfare services: Bridging family needs and child welfare mandates. Child Welfare, 88(1), 101–126.

Konrad, S. C. (2007). What parents of seriously ill children value: Parent-to-parent connection and mentorship. Omega, 55(2), 117–130.

Koroloff, N. M., Friesen, B. J., Reilly, L., & Rinkin, J. (1996). The role of family members in systems of care. In B.A. Stroul (Ed.), Children’s mental health: Creating systems of care in a changing society (pp. 409–426). Baltimore: P.H. Brookes Publishing.

Kutash, K., Acri, M., Pollock, M., Armusewicz, K., Olin, S., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2014). Quality indicators for multidisciplinary team functioning in community-based children’s mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(1), 55–68.

Kutash, K., Duchnowski, A. J., Green, A. L., & Ferron, J. M. (2011). Supporting parent who have youth with emotional disturbances through a parent-to-parent support program: A proof of concept study using random assignment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(5), 412–427.

Kutash, K., Garraza, L. G., Ferron, J. M., Duchnowski, A. J., Walrath, C., & Green, A. L. (2013). The relationship between family education and support services and parent and child outcomes over time. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders, 21(4), 264–276.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Mann, C. (2013). Joint CMCS and SAMHSA informational bulletin: Coverage of behavioral health services for children, youth, and young adults with significant mental health conditions. Baltimore, MD: Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Matarese, M., & Harburger, D. (2014) Technical Assistance on the Integration of Health Homes and Managed Care for Children with Behavioral Health Needs. New York: Presentation presented at the New York State Planning Meeting, Albany.

McKay, M. M., & Bannon, W. (2004). Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 13, 905–921.

McKay, M. M., Nudelman, R., McCadam, K., & Gonzales, J. (1996). Evaluating a social work engagement approach to involving inner-city children and their families in mental health care. Research on Social Work Practice, 6(4), 462–472.

Miles, P. (2008). Family partners and the Wraparound process. In E.J. Bruns & J.S. Walker (Eds.), The resource guide to wraparound (Chapter 4b.3). Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative, Research and Training Center for Family Support and Children’s Mental Health.

Miles, P., & Brown, N., The National Wraparound Initiative Implementation Work Group. (2011). Wraparound implementation guide: A handbook for administrators and managers. Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Morse, J. M. (2000). Determining sample size. Qualitative Health Research, 10(3), 3–5.

Munsell, E. P., Cook, J. R., Kilmer, R. P., Vishnevsky, T., & Strompolis, M. (2011). The impact of child and family team composition on wraparound fidelity: Examining links between team attendance consistency and functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(6), 771–781.

Obrochta, C., Anthony, B., Armstrong, M., Kalil, J., Hust, J., & Kernan, J. (2011). Issue brief: family-to-family peer support: Models and evaluation. Atlanta, GA: ICF Macro. Outcomes Roundtable for Children and Families.

Olin, S. S., Kutash, K., Pollock, M., Burns, B. J., Kuppinger, A., & Craig, N., et al. (2014). Developing quality indicators for family support services in community team-based mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(1), 7–20.

Olin, S., Shen, S., Rodriguez, J., Radigan, M., Burton, G., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Parent depression and anger in peer-delivered parent support services. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 24(11), 3383.

Osher, T., & Penn, M. (2008). Family partners in systems of care and wraparound. Focal Point Research, Policy, and Practice in Children’s Mental Health, 22(1), 16–18.

Palit, A., & Chatterjee, A. (2006). Parent-to-parent counseling – a gateway for developing positive mental health for the parents of children that have cerebral palsy with multiple disabilities. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 29(4), 281–288.

Patton, M. Q. (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research, 34(5 Pt 2), 1189–1208.

Penn, M., & Osher, T. (2008). The application of the ten principles of the wraparound process to the role of family partners on wraparound teams. In E.J. Bruns & J.S. Walker (Eds.), The resource guide to wraparound (Chapter 4b.1). Portland, OR: Portland State University, Research and Training Center on Family Support and Children’s Mental Health, National Wraparound Initiative.

Pires, S. A. (2013). Customizing health homes for children with serious behavioral health challenges. Rockville, MD: U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Rhodes, P., Baillee, A., Brown, J., & Madden, S. (2008). Can parent-to-parent consultation improve the effectiveness of the Maudsley model of family-based treatment for anorexia nervosa? A randomized control trial. Journal of Family Therapy, 30(1), 96–108.

Rodriguez, J., Olin, S. S., Hoagwood, K. E., Shen, S., Burton, G., Radigan, M., & Jensen, P. S. (2011). The development and evaluation of a parent empowerment program for family peer advocates. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20(4), 397–405.

Ruffolo, M. C., Kuhn, M. T., & Evans, M. E. (2005). Developing a parent-professional team leadership model in group work: Work with families with children experiencing behavioral and emotional problems. Social Work, 51(1), 39–47.

Santelli, B., Turnbull, A. P., Marquis, J. G., & Lerner, E. P. (1995). Parent to parent programs: A unique form of mutual support. Infants and Young Children, 8(2), 48–57.

Slowik, M., Willson, S. W., & Loh, E. C. (2004). Service innovations: Developing a parent/carer support group in an inpatient adolescent setting. Psychiatric Bulletin, 28(5), 177–179.

Staudt, M. (2007). Treatment engagement with caregivers of at-risk children: Gaps in research and conceptualization. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 16(2), 183–196.

Stephens, T., Gopalan, G., Bowman, M., Acri, M., & McKay, M. M. (In press). Culturally relevant trauma-informed family engagement with families experiencing high levels of exposure to trauma and stress. In V. Strand, G. Sprang & L. Ross (Eds.), Developing Trauma Informed Child Welfare Agencies and Services. New York: Springer.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Suter, J. C., & Bruns, E. J. (2009). Effectiveness of the wraparound process for children with emotional and behavioral disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12(4), 336–351.

Van Den Berg, J., Bruns, E.J., & Burchard, J. (2008). History of the wraparound process. In E. J. Bruns & J. S. Walker (Eds.), The resource guide to wraparound (Chapter 1.3). Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative, Research and Training Center for Family Support and Children’s Mental Health.

Walker, J. S. (2008). How, and why, does wraparound work: A theory of change. Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative.

Walker, J. S., & Bruns, E. J. (2006). Building on practice-based evidence: Using expert perspectives to define the wraparound process. Psychiatric Services, 57(11), 1579–85.

Walker, J. S., & Schutte, K. (2005). Quality and individualization in wraparound team planning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(2), 251–267.

Wisdom, J. P., Lewandowski, R. E., Pollock, M., Acri, M., Shorter, P., & Olin, S. S., et al. (2014). What family support specialists do: Examining service delivery. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41(1), 21–31.

Author Contributions

G.G. designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses, and wrote the paper. M.J.H. collaborated with the design, data analysis and writing of the study. E.B. collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript. M.C. analyzed data, and contributed to writing and editing of the final manuscript. S.M. analyzed data, and contributed to writing and editing of the final manuscript. M.P. analyzed data, and contributed to writing and editing of the final manuscript. T.L. analyzed data, and contributed to writing and editing of the final manuscript. M.M. collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gopalan, G., Horen, M.J., Bruns, E. et al. Caregiver perceptions of Parent Peer Support Services within the Wraparound Service Delivery Model. J Child Fam Stud 26, 1923–1935 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0704-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0704-x