Abstract

Child-onset mental health disorders can have a profound impact on the family, and particularly caregivers, particularly if they lack the needed support and information to manage their child’s treatment needs. The parent peer movement in children’s mental health directly responds to this gap in support of caregivers: Parent peers, who are caregivers of children with mental health difficulties who have experience navigating child serving systems, typically provide information about mental health and treatment, foster linkages to services, and offer emotional support to similarly situated caregivers. This chapter provides an overview of parent peer support, including the roles and qualifications of parent peers in the child mental health system, theoretical models that guide parent peer support programs, existing research, and concludes with the needed future directions.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

An estimated 1.9–6.1 million children between the ages of 3 and 17 have a diagnosable mental health condition including anxiety, depression, and oppositional defiant disorder [1]. The intractable and chronic nature of many mental health disorders, coupled with a lack of appropriate treatment and support, have a deleterious impact upon a child’s educational and occupational functioning, relationships, and physical, emotional, and behavioral health [2,3,4]. Child-onset mental health difficulties also have a significant impact upon the family. Alongside parenting challenges associated with their child’s mental health problems, caregivers are tasked with overseeing and advocating for their child’s treatment needs in a barrier-laden service system [5, 6], yet they often lack their own emotional support and information about resources, services, and information about treatment options for their child [6]. These difficulties, coupled with experiencing burden, stigma, and blame for their child’s condition [5, 6], puts caregivers at high risk for stress, strain, and emotional distress [5, 7,8,9,10,11,12].

Supporting caregivers is of paramount importance for the health and wellbeing of the entire family; reduction in parental stress, for example, not only enhances the emotional health of parents but is also associated with improvements in therapeutic outcomes among youth [13]. However, the child mental health system has historically subverted caregivers’ needs, and their involvement in treatment has been primarily to support the child [14]. In the 1980s, a new model of service delivery was formalized in which parent peers, defined as trained parents/primary caregivers of children with mental health needs, provided similarly situated families with an array of services such as emotional support, information about mental health and treatment, and linkages to services for the child and themselves [14]. This chapter provides an overview of parent peers and the services they provide, including the multiple theories underlying parent peer support programs, evidence supporting these models, and future directions for the field.

Qualifications and Roles

Parent peers are referred to in the literature as peer support specialists, peer and parent advocates, family peer advocates, and family or parent advisors. By definition, a parent peer has to have had lived experience as the primary caregiver for a child with a mental health problem and has navigated the child-serving system [14,15,16,17], as it is their lived experience that is believed to make them uniquely qualified to engage parents and caregivers facing similar issues [18, 19]. Additional criteria vary but may also include age and educational requirements (e.g. being 18 years of age or older and having a high school diploma), completion of trainings, holding a valid credential, and prior paid or volunteer experience working or volunteering providing peer parent support [20].

Unlike other peer models, parent peers focus on the parent/primary caregiver and support them to take an active role in decision-making, navigating services, and developing their capacity to meet the needs of their child and family. This often occurs in collaboration with clinicians and other providers who are focused more centrally on the child’s treatment needs. Within this capacity, the roles that parent peers assume are multifaceted, yet comprised primarily of providing education and information, facilitating linkages to supports, and providing emotional support, skill development, and advocacy.

By way of example, Hoagwood and colleagues [14] conducted a review and synthesis of family support programs and found that peers engage in services which include: informational/ educational support (for example, providing families with information about resources that may be available to them); instructional/skills development (for example, coaching caregivers on effective ways to address their child’s behaviors); emotional and affirmation support (promoting caregivers’ feelings of being affirmed and appreciated); instrumental support (such as providing concrete services); and advocacy (such as assisting parents to understand their rights and advocate effectively for the services their child is entitled to.)

Formal training programs for these roles are beginning to emerge. Rodriguez and colleagues [21] describe the development and evaluation of a professional program to enhance parent peers’ professional skills, called the Parent Empowerment Program (PEP). The PEP training was originally designed as a 5-day in-person training and currently consists of a combination of online self-learning modules followed by a two-day in-person training and a series of 12 weekly group coaching calls. PEP training fulfils the training requirement for the New York State Family Peer Advocate Credential (FPA). Approximately 400 individuals currently hold a valid FPA Credential [22]. Evaluation of the training program provided systematically collected information about peer activities over time. It indicated that the job functions of parent peer workers include provision of information/education, advocacy, tangible assistance, and emotional support, but that emotional support and service access issues appear to be a key focus of the peer’s role.

Theory

Often, reports of any peer-delivered intervention do not state an explicit theory about the mechanisms underlying how it will impact the outcomes under investigation, but rather center around a series of values, ideas, and beliefs [23]. Without an underlying theory, it is difficult to know if these mechanisms are being carried through into practice, which can lead to a lack of congruence between design, implementation, and evaluation [23]. Therefore, theories are necessary to understand how parent peer programs are intended to work, along with the expected intermediate and long-term changes in caregiver, child, and family outcomes.

A theoretical basis for understanding the potential effectiveness of peer support has been offered in the literature to a limited extent. One theory is Festinger’s Social Comparison Theory . This theory postulates that individuals self-evaluate based on the comparison of their own beliefs and desires against those of another person’s [24]. It proposes that individuals seek to improve their self-esteem and enhance themselves by making comparisons with others [25]. Within the context of peer support, vulnerable or at-risk individuals work with peers who have made successful changes, thereby encouraging comparison and positive behavior change [26]. Moreover, people are more likely to compare themselves to another when they perceive the person to be similar to themselves. Parent peers may be perceived by individuals to be more similar than a traditional clinician, due to their shared lived experience. This shared connection may provide common ground between the two individuals upon which to change [26].

A second theory which may provide a theoretical rationale for the value of peer support is Bandura’s Social Learning Theory . This theory posits that behavior is learned from the environment through the process of observational learning [27]. In other words, desirable behaviors are modeled and the effects of these behaviors can be determined in the process of observational learning. These observed and newly learned behaviors can then serve as a guide for future action [26]. Within the context of peer support, parents have the opportunity to observe new behaviors through role modeling from a parent peer [28], which may enhance the caregiver’s confidence, perceived empowerment and sense of personal agency.

Rogers’ Diffusion of Innovation theory [29] has also been offered as an explanatory framework for peer support. This theory explains how an idea or new behavior gains momentum and is “adopted” by others. Adoption of new or innovative behaviors relies on the perception that they are superior to current behavior, that they align with one’s values, and that there are opportunities to observe what happens when others adopt the new behaviors. Although specific to youth peers, an Australian study that aimed to identify the key features, impacts, and outcomes associated with peer-based programs draws on this theory to explain how, in a group peer program, long-standing or negative attitudes or beliefs can change through exposure to positive coping strategies adopted by credible and positive peer role models. New innovative and acceptable behaviors that were adopted in their youth peer-based program included improved help-seeking behavior, pro-social behaviors, and alternatives to risk behaviors [30].

Aside from specific theories, key components that are responsible for the positive impacts of peer support have been identified in the literature. Because of their personal experience, parent peers have credibility and are able to engender trust. Shared experiences also enable parent peers to adopt a nonjudgmental attitude [31]. In the case of parent peer programs, these trusting relationships can assist caregivers in becoming more actively engaged in their child’s services [32,33,34,35,36,37]. In this same way, parent peers are often seen as authentic because they can relate to common challenges and have found their way to support their child and family to move forward in positive ways. This lived-experience helps the families be hopeful that things can get better.

Research Evidence

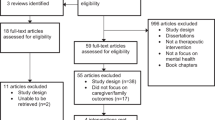

The diversity of roles and settings in which parent peers work is reflected in the research about these models. A synthesis of this literature identifies four main foci: (1) the feasibility and acceptability of peer programs; (2) mental health services utilization, (3) caregiver and family processes, and, (4) symptoms and functioning.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Feasibility and acceptability studies primarily test innovative models in which the program is being delivered in a new setting or the role of the peer deviates from the typical services they offer. A consensus of these studies suggests that parent peer programs are highly feasible to deliver and perceived as being acceptable from the perspectives of caregivers and peers. For example, Acri et al. developed and tested a detection and outreach model in which parent peers screened caregivers for symptoms of depression, provided information about mental health and treatment, connected at-risk caregivers to mental health services for a formal assessment, and using an evidence-informed approach, taught caregivers how to be empowered participants in their treatment. This model was tested both in freestanding family support organizations, which serve caregivers of children with emotional and behavioral problems [38, 39], and in the child welfare system [15, 40]. In both studies, results showed the intervention was highly feasible to deliver, based upon metrics including number of sessions completed, fidelity to the intervention, and attendance, and acceptable from the perspectives of parent peers and caregivers in that peers felt comfortable delivering the intervention and caregivers viewed parent peers inquiring about their mental health favorably. Moreover, Butler and Titus [16] found a preventative peer-delivered parenting intervention delivered in primary care settings for families of preschool youth at risk for behavior problems was feasible for parent peers to deliver as measured by the number of physicians who referred caregivers to peers, the number of peers who completed the training and caregiver attendance. And, January et al. [5] found that a telephone intervention for caregivers of children at risk for behavioral or emotional problems was delivered with fidelity, which is an important criterion for assessing feasibility.

Mental Health Services Utilization

Peer-delivered services also appear to facilitate treatment utilization for caregivers. For example, caregivers at risk for depression who participated in Acri et al. [38, 39] detection and outreach model and reported a strong working alliance with their parent peer were also more likely to access mental health services and reported fewer perceived barriers to help seeking (Hamovitch et al., in press). This finding is consistent with results of Radigan et al. [41] study, which surveyed over 1200 caregivers across New York State who had accessed public mental health services and found that caregivers who worked with a parent peer attended more mental health sessions for themselves than caregivers who did not utilize parent peer services, and evidenced significantly greater satisfaction with services and overall satisfaction as well.

However, the evidence isn’t quite as clear for child service use. Specifically, Hoagwood et al. [14] reviewed two published studies that examined child treatment engagement: The first found the parent peer program, which aimed to facilitate treatment utilization prior to beginning Oregon’s Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment Program, was associated with the child’s initial engagement into treatment, but had no impact upon ongoing use of services or attendance [35]. The second study, which tested Parent Connectors, a telephone-based program for caregivers of children receiving special education and who had emotional problems, did not find any discernible impact of the peer program upon the child’s utilization of treatment [42].

Caregiver and Family Processes

Studies of caregiver and familial processes also vary. Specifically, Hoagwood et al. [43] Parent Empowerment Program, which aimed to train parent peers to empower and activate caregivers to engage their children into mental health services, found no impact upon caregiver strain or empowerment, while Kutash et al. [42] Parent Connectors found significant improvements from pre- to posttest on family empowerment, but only among those who were experiencing the high levels of strain. Further, Koroloff et al. [35] found that the EPSDT pretreatment program was associated with slight improvements in the caregiver’s sense of empowerment comparative to a matched comparison group. And, January et al. [5] found significant pre- to post-improvements in the caregiver’s perception of social and concrete (e.g., access to supports and resources) as a result of a peer parent support program delivered by phone.

Child and Caregiver Symptoms and Functioning

A synthesis of this literature suggests that peer models are associated with multiple, positive outcomes for children and their caregivers. Results of a recent randomized controlled trial of a parent peer-delivered educational and supportive group for ethnically and racially diverse families of children with autism spectrum disorder found that caregivers in the intervention condition exhibited significant improvements in knowledge about autism and reductions in caregiver stress in comparison to caregivers receiving treatment as usual (referrals to services in the community) [44].

Additionally, studies of peer-delivered parenting programs found several improvements in child and caregiver outcomes. In comparison to a waitlist control group, for example, caregivers who received a peer-delivered parenting program evidenced significant improvements in their concerns about their child and parenting, and their children showed significant improvements in behavior, although there was no difference between this group and a waitlist control group regarding parent stress [45]. Butler and Titus [16] found a peer-delivered parenting skills intervention was associated with significant improvements in parent-reported behavior problems and parenting stress and competence from pre- to posttest, although the frequency of their preschool child’s behavior problems was not significantly impacted. And, Chacko et al. [46] who examined a parent peer-delivered parenting program for families of children with ADHD found that the intervention, coupled with medication, was linked to improvements in child behavior symptoms and functioning as well as reductions in parenting stress and improved parenting behavior. However, neither Hoagwood et al. [43] nor Kutash et al. [42] found improvements in child behavior or emotional functioning due to the Parent Empowerment Program training or the Parent Connectors programs, although the primary targets for these interventions were caregiver empowerment, activation, and support, and not child emotional health or functioning.

Taken as a whole, the emerging research on parent peer models is favorable; peer-delivered interventions appear to be feasible to administer and acceptable to key stakeholders, facilitate service use by caregivers to address their own behavioral healthcare needs, increase caregiver knowledge, and improve child and caregiver emotional health and functioning. To this latter point, parenting skills programs appear to be the most effective for decreasing mental health symptoms, improving the child’s functioning, reducing caregiver stress, and enhancing parenting.

Future of Peer Programs

Peer-delivered services have expanded dramatically both in the United States and globally [47]. Peer parents assume a range of roles and are embedded in a variety of settings, most states have established credentialing requirements, and parent peer delivered services are, or will soon be, a billable service under Medicaid across the United States [16, 48]. The research on parent peer models is encouraging and shows several areas of growth, including detection and outreach models for caregivers at risk (e.g., Acri et al. [38, 39]), integrated and co-located models [16, 46], and preventive programs for at-risk youth [5]. Efforts such as these illustrate the growth and promise of parent peer models for families of children with mental health difficulties.

References

Data and statistics on children’s mental health. Retrieved from https://www.someaddress.com/full/url/.

Bellis MA, Lowey H, Leckenby N, et al. Adverse childhood experiences: retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviors and health outcomes in a UK population. J Public Health. 2013;36:81–91.

Costello EJ, Angold A, Keeler GP. Adolescent outcomes of childhood disorders: the consequences of severity and impairment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(2):121–8.

Washburn J, Teplin L, Voss L, et al. Psychiatric disorders among detained youths: a comparison of youths processed in juvenile court and adult criminal court. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:965–73.

January SAA, Hurley KD, Stevens AL, Kutash K, Duchnowski AJ, Pereda N. Evaluation of a community-based peer-to-peer support program for parents of at-risk youth with emotional and behavioral difficulties. J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25:836–44.

Shor R, Birnbaum M. Meeting unmet needs of families of persons with mental illness: evaluation of a family peer support hotline. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:482–8.

Addington J, McCleery A, Addington D. Three-year outcome of family work in an early psychosis program. Schizophr Res. 2005;79:107–16.

Angold A, Messer SC, Stangl D, Farmer EMZ, Costello EJ, Burns BJ. Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:75–80.

Bademli K, Duman L. Effects of a family-to-family support program on the mental health and coping strategies of caregivers of adults with mental illness: a randomized controlled study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28:392–8.

Chien WT. Effectiveness of psychoeducation and mutual support group program for family caregivers of Chinese people with schizophrenia. Open Nurs J. 2008;2:28–39.

Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, Lucksted A, Cohen M, Falloon I, et al. Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:903–10.

Wu P, Hoven CW, Bird HR, Moore RE, Cohen P, Alegria M, et al. Depressive and disruptive disorders and mental health service utilization in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:1081–90.

Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:504–15.

Hoagwood KE, Cavaleri MA, Olin SS, Burns BJ, Slaton E, Gruttadaro D, Hughes R. Family support in children’s mental health: a review and synthesis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13:1–45.

Acri M, Hamovitch E, Gopalan G, Lalayants, M. Examining the impact of a peer-delivered program for child welfare involved caregivers upon depression and engagement in mental health services. Under Review.

Butler AM, Titus C. Pilot and feasibility study of a parenting intervention delivered by parent peers. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2017;12:215–25.

Gopalan G, Lee SJ, Harris R, Acri MC, Munson M. Utilization of peers in services for youth with emotional and behavioral challenges: a scoping review. J Adolesc. 2017;55:88–115.

Davidson L, Bellamy C, Guy K, Miller R. Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry. 2012;11:123–8.

Oh H, Solomon P. Role-playing as a tool for hiring, training, and supervising peer providers. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2014;41:216–29.

National Certified Peer Specialist (NCPS) Certification. Downloaded August 29, 2019 from https://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/national-certified-peer-specialist-ncps-certification-get-certified.

Rodriguez J, Olin SS, Hoagwood KE, Shen S, Burton G, Radigan M, et al. The development and evaluation of a parent empowerment program for family peer advocates. J Child Fam Stud. 2011;20:397–405.

Families Together in New York State (FTNYS). FPA credentialing update report; 2019.

Trickey H. Peer support: how do we know what works? 2016. Retrieved from https://orca.cf.ac.uk/91931/3/Trickey%20Peer%20support.pdf.

Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat. 1954;7:117–40.

Wood JV. Theory and research concerning social comparisons of personal attributes. Psychol Bull. 1989;106:231.

Barton J, Henderson J. Peer support and youth recovery: a brief review of the theoretical underpinnings and evidence. Can J Family Youth. 2016;8:1–17.

Bandura A. Observational learning. In: Donsbach W, editor. The international encyclopedia of communication. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2008. p. 3359–61.

Miller PH. Theories of developmental psychology. New York, NY: Worth Publishers; 2010.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations: third edition. New York: The Free Press; 1983.

Hildebrand J, Lobo R, Hallett J, Brown G, Maycock B. My-peer toolkit: developing an online resource for planning and evaluating peer-based youth programs. Youth Stud Aust. 2002;31:53–61.

Mourra S, Sledge W, Sells D, Lawless M, Davidson L. Pushing, patience, and persistence: peer provider perspectives on supportive relationships. Am J Psychiatr Rehabil. 2014;17:307–28.

Gyamfi P, Walrath C, Burns BJ, Stephens RL, Geng Y, Stambaugh L. Family education and support services in systems of care. J Emot Behav Disord. 2010;18:14–26.

Hoagwood KE. Family-based services in children’s mental health: a research review and synthesis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46:670–713.

Koroloff NM, Elliott DJ, Koren PE, Friesen BJ. Connecting low-income families to mental health services: the role of the family associate. J Emot Behav Disord. 1994;2:240–6.

Koroloff NM, Elliott DJ, Koren PE, Friesen BJ. Linking low-income families to children’s mental health services: an outcome study. J Emot Behav Disord. 1996;4:2–11.

Osher T, Penn M, Spencer SA. Partnerships with families for family-driven systems of care. In: Stroul BA, Blau GM, editors. The system of care handbook: transforming mental health services for children, youth, and families. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing; 2008. p. 249–74.

Robbins V, Johnston J, Barnett H, Hobstetter W, Kutash K, Duchnowski AJ, et al. Parent to parent: a synthesis of the emerging literature. Tampa: University of South Florida, The Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, Department of Child & Family Studies; 2008.

Acri MC, Frank S, Olin SS, Burton G, Ball JL, Weaver J, Hoagwood KE. Examining the feasibility and acceptability of a screening and outreach model developed for a peer workforce. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24:341–50.

Acri M, Olin SS, Burton G, Herman RJ, Hoagwood KE. Innovations in the identification and referral of mothers at risk for depression: development of a peer-to-peer model. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23:837–43.

Hamovitch EK, Acri M, Gopalan G. Relationships between the working alliance, engagement in services, and barriers to treatment for female caregivers with depression. Child Welfare. In Press.

Radigan M, Wang R, Chen Y, Xiang J. Youth and caregiver access to peer advocates and satisfaction with mental health services. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50:915–21.

Kutash K, Duchnowski AJ, Lynn N. School-based mental health: an empirical guide for decision-makers. Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, Department of Child and Family Studies, Research and Training Center for Children’s Mental Health; 2006.

Hoagwood K, Rodriguez J, Burton G, Penn M, Olin S, Shorter P, et al. Parents as change agents: the Parent Empowerment Program for parent advisors in New York state. Paper presented at the 22nd Annual Research Conference: a system of care for children’s mental health: expanding the research base, Tampa, FL; 2009.

Jamison JM, Fourie E, Siper PM, Trelles MP, George-Jones J, Grice AB, et al. Examining the efficacy of a family peer advocate model for Black and Hispanic caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47:1314–22.

Day C, Michelson D, Thomson S, Penney C, Draper L. Evaluation of a peer led parenting intervention for disruptive behaviour problems in children: community based randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2012;344:605–8.

Chacko A, Hopkins K, Acri M, Mendelsohn A, Dreyer B. Connecting service delivery systems to expand ADHD service provision in urban socioeconomically disadvantaged communities: a proof of concept study. Under review.

Repper J, Carter T. A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. J Ment Health. 2011;20:392–411.

Nicholson J, Valentine A. Key informants specify core elements of peer supports for parents with serious mental illness. Front Psych. 2019;10:106–31.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Acri, M.C., Hamovitch, E., Kuppinger, A., Burger, S. (2021). Parent Peer Models for Families of Children with Mental Health Problems. In: Avery, J.D. (eds) Peer Support in Medicine. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58660-7_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58660-7_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-58659-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-58660-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)