Abstract

Survey (n = 161) and focus group (n = 15) methods were used to collect data from a community sample of New Zealand fathers about their knowledge and experience with parenting programs, and their preferences for program content, features, and delivery methods. The prevalence of perceived child behavioral and emotional difficulties, parenting risk and protective factors, fathers’ parenting confidence, and the family and personal correlates of father preferences were also examined. Survey results showed that fathers’ knowledge and experience of available parenting programs was low. The topics rated most highly by fathers to include in a program were building a positive parent–child relationship, increasing children’s confidence and social skills, and the importance of fathers to children’s development. Fathers’ most preferred program delivery methods were father only group programs, individually-tailored programs, and a range of low intensity options, including seminar, television series, and web-based. Program features most likely to influence father attendance were demonstrated program effectiveness, location of sessions, practitioner training, and that content addressed personally relevant issues. Fathers’ level of education, stress and depression, and perceptions of child behaviour difficulty were linked to program content and delivery preferences. New insights were gained from focus group participants about messages to include in program advertisements and program content to emphasise in order to engage fathers. Findings highlight a variety of program and delivery options that could be offered to meet a range of father parenting support needs, including concerns about coping with specific child behaviours and emotions, and managing personal and parenting stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Extensive evidence shows that parenting interventions based on social learning principles are an effective treatment for behavior problems in children (Dretzke et al. 2009; Eyberg et al. 2008). However, the majority of parents who have concerns about their children’s behavior or adjustment do not receive services, highlighting the need for a public health approach to the provision of evidence-based parenting intervention strategies (Sanders 2012). To reach as many people as possible, a public health approach has a focus on ensuring that parenting intervention strategies are widely available in easily accessible formats and delivery mechanisms (Metzler et al. 2012). This approach contrasts with the traditional clinical treatment model of parenting interventions based on highly intensive practitioner-delivered interventions to targeted individuals.

Fathers are one group of parents who have been identified by researchers and clinicians as experiencing barriers to participation in parenting interventions (Fabiano 2007). There are several key reasons why increased father involvement in parenting interventions is needed. First, a large body of research indicates that children with behavior problems early in life are at risk for a range of long-term negative outcomes (Knoster 2003). Furthermore, poor father child relationships have been found to precipitate delinquent behaviors in adolescents (Atwood et al. 1989), and low levels of father involvement have been found to affect children’s school achievement and aggression, and heighten the likelihood of engagement in risky behaviors (McLanahan and Teitler 1999). Second, behavior problems in young children are more likely to persist in the context of difficult parent–child relationships, highlighting the need for early parenting interventions, especially with fathers (Cowan and Cowan 2002). Third, current research on fathers’ unique contribution to children’s behavioral development suggests the possibility that increased father involvement in parenting programs is likely to be highly beneficial for young children with disruptive behavior problems (Bogels and Phares 2008; Fabiano 2007; Tiano and McNeil 2005). Finally, a growing body of research shows that when fathers are involved in parenting interventions outcomes are improved for children, mothers and fathers (Bagner and Eyberg 2003; Sanders et al. 2013; Webster-Stratton and Hammond 1997).

Despite the many potential benefits of father involvement in parenting programs, fathers generally have low participation rates and when fathers are included program adherence is often problematic, with low attendance and high attrition (Tiano and McNeil 2005). A variety of reasons have been suggested for low father participation, including the way programs are advertised and promoted to families, and aspects of program content and delivery (Addis and Mahalik 2003; Fabiano 2007). For example, parent training that is promoted in a way that could be interpreted as parents lacking a skill may deter fathers, as it has been suggested that men are unlikely to seek help if doing so means admitting there is a problem (Addis and Mahalik 2003; Fabiano 2007). In addition, most programs do not differentiate between the treatment role of mothers and fathers (Lee and Hunsley 2006) when the parenting tasks of each parent may differ greatly, and as a result the content of parenting programs may be viewed by fathers as being less relevant to their needs compared to mothers (Fabiano 2007). If fathers are not engaged or do not find the program content relevant they are less likely to implement the techniques, leading to decreased program effectiveness (Fabiano 2007). Other key barriers that have been identified to fathers accessing parenting programs and family services include a lack of information about the services available, fear of not knowing what the program will involve, and how fathers will be perceived by other men if they seek help (Anderson et al. 2002; Berlyn et al. 2008; Fabiano 2007).

To better understand why fathers are not involved in parenting interventions and to create programs that will better meet the needs of both fathers and mothers, it is important to obtain fathers’ perspectives. The use of consumer preference data to inform program development has been widely practiced across multiple disciplines, most notably marketing, and is beginning to be used in the development of psychological interventions (Kirby and Sanders 2012; Santucci et al. 2011). When program developers converse directly with a target group it is likely to improve the quality and relevance of the program to that specific group, and as a result increase participation and engagement (Kirby and Sanders 2012).

A small number of consumer research studies on family relationships and life skills services for fathers have provided insight into fathers’ reasons for accessing support. For example, survey and interview data from Australian men who participated in family and relationships services found that 37 % of the sample sought help in response to a relationship crisis, while 43 % were looking for advice or support. Many felt it was important that the service provider had experience working with men, but gender of the provider was not an influential factor in their participation (O’Brien and Rich 2003). This contrasts with findings reported in other studies of father consumers, program facilitators, and social workers, who argued that male facilitators are necessary to increase father engagement and involvement (Berlyn et al. 2008; Lazar et al. 1991). Other consumer research has offered insight into possible ways to attract and engage fathers in programs. In focus group work by Anderson et al. (2002), fathers who were previously or currently involved in a family service program suggested hosting father–child events to promote programs, and offering incentives to get fathers involved initially (Anderson et al. 2002). Other ideas for maximising engagement included increasing the visibility of programs, identifying specific needs of participants, and using the positive and constructive feelings that fathers have about their children to get them motivated and involved (Anderson et al. 2002). Both the O’Brien and the Anderson studies gathered information from men who were or had been actively involved in programs. Attaining the perspectives of fathers who have recently participated in programs is beneficial, however, community surveys are needed to gain a broader understanding of fathering support needs and preferences for program content and delivery and to identify barriers to participation.

Currently, there is limited father data available from community surveys. One study that does have father preference data comes from a UK web-based survey of 721 working parents, that investigated preferred features for a parenting program delivered in the workplace (Sanders et al. 2011a, b). Program features rated most important by both fathers and mothers were demonstrated program effectiveness, the program is conducted by trained practitioners, and the content addresses personally relevant issues (Sanders et al. 2011a, b).

These types of father surveys also need to obtain information about father reports of child behavior problems and the associated paternal risk and protective factors to identify fathers that would most benefit from participation in parenting interventions. To date, only a few studies provide this type of data (Dave’ et al. 2008; Sanders et al. 2010). For example, an epidemiological survey of 933 Australian fathers found that 3 % rated their child’s behavior as very or extremely difficult, and 14 % reported feeling very or extremely stressed (Sanders et al. 2010). Fathers with more difficult children were more likely to perceive parenting to be demanding, stressful, and depressing, and less rewarding. These fathers also reported high levels of personal stress and were less likely to have completed secondary school. Only 11 % of the fathers surveyed had participated in a parenting program in the previous 12 months. Those fathers who had previously participated in a parenting program were more likely to have higher income and education, and report higher levels of stress and child behavior difficulties (Sanders et al. 2010). These last findings are helpful for providing some insight into variables that may influence father participation. However, few if any studies have examined factors that may influence fathers’ program content and delivery preferences. Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact parents’ expectations and desires for their children’s development and the role parents see for themselves in achieving those outcomes (for a review see Hoff et al. 2002). Thus it is possible that parents’ program content choices may vary as a function of socioeconomic status.

The goal of the present study was to obtain an understanding of the fathering support needs and parenting program preferences among New Zealand fathers with a child aged 2–9 years. A survey of an unselected community sample of fathers was undertaken to identify: (a) fathers’ perceptions of child behavior problems; (b) the prevalence of modifiable parenting risk (father stress, depression, parenting confidence and perceptions of parenting) and protective factors (parenting support); (c) fathers’ knowledge of and experience with parenting programs; (d) what topics fathers considered important to include in a program; (e) program delivery methods that fathers would find useful; and (f) program features that would influence fathers to participate. Links between father-reported family and personal characteristics and fathers’ program content and delivery preferences were also explored. The second phase of the project involved a series of focus groups designed to elicit qualitative information regarding program content and delivery modality, along with ideas for recruitment and promotion strategies to attract and engage fathers. A mixed method approach was used given that survey methods are useful in gaining the perspectives of a large number of people within a target group with minimal time and resource costs. When supplemented by qualitative methods, such as focus groups, more in-depth insights may be obtained into barriers to participation and ways to tailor programs specifically to the needs and preferences of specific groups (Sanders and Kirby 2011).

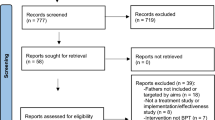

Method

Participants

Survey

A community sample of 161 New Zealand fathers with at least one child between the ages of 2–9 years (M = 57 months, SD = 27 months, 51 % female) completed the survey portion of the study. Ninety-nine percent of the respondents were the child’s biological father and two (1 %) were step fathers. The majority of participants were living with their child’s other biological parent (85 %) with a smaller number of single parent (10 %) and blended (5 %) families. The majority of fathers had between one and three children living in their household (M = 1.79, SD = 0.90). The fathers had a mean age of 37.82 years (SD = 7.30), and were predominantly New Zealand European (69 %), with smaller numbers from Māori (7 %), Pacific Island (3 %), Asian (4 %) and European (United Kingdom and Europe 11 %), North America (2 %), and South Africa (2 %) origins. Participants were from a range of socio-demographic backgrounds, although the majority had a post-secondary qualification (trade or technical college certificate 21 %; university qualification 36 %; advanced University degree 25 %), were employed full time (80 %) and received a moderately high income (19 % earning <NZ$50 000, 43 % earning NZ$50,000–100,000, and 38 % earning >NZ$100,000). (The median annual family income in New Zealand in 2010 was $64,272, Statistics New Zealand 2010).

Focus Groups

Focus group participants were 15 fathers who had between two and six children (M = 2.91, SD = 1.22) aged 2–9 years. They were of varying occupations (three stay-at-home fathers, six manual labourers, four professionals, and two self-employed business owners) and ethnic groups (European 60 %, Pacific Island 20 %, Māori 13 %, and Filipino 7 %) and the majority (93 %) were parenting with a partner.

Measures

The survey questions covered family background and personal information, including family composition, income and father education. Fathers were asked to report their perceptions of child behavior problems, and their confidence in dealing with these difficulties, as well as their parenting experience and feelings of stress and depression over the past 6-months. Fathers were asked about their knowledge of and participation in parenting programs and to rate their preferences for program content, features and delivery modes. These questions are explained in more detail in the following sections.

Child Behavior, Parenting Experiences, and Paternal Stress and Depression

Fathers’ perceptions of child behavior problems were assessed using questions from the strengths and difficulties (SDQ) impact supplement (Goodman and Gotlib 1999). The specific questions asked ‘do you think your child has any difficulties in the following areas, emotions, concentration, behavior or being able to get along with other people? For each of these four areas fathers were asked to indicate whether their youngest child between the ages of 2–9 years, had no difficulty, minor difficulties, definite difficulties or severe difficulties over the last 6 months. Questions of parenting confidence, experience, and stress and depression were drawn from Sanders et al. (2010). Fathers’ parenting confidence was based on ratings of how confident fathers felt in dealing with seven difficult child behaviors (e.g., how confident are you that you can successfully deal with your child if s/he constantly seeks attention), using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Fathers were also asked to rate their experience of parenting over the past month, specifically whether parenting was rewarding, demanding, stressful, fulfilling or depressing. Ratings were made on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). Fathers’ mental health was assessed with two items asking to what extent have you felt stressed/depressed over the past month on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely).

Knowledge and Experience of Parenting Programs

Fathers were provided with a list of eight parenting programs available in New Zealand. For each of the programs, fathers were asked to indicate if they had heard of the program or not, and whether they had ever attended the program (either in the past 12 months or more than 12 months ago). Those fathers who had previously attended a parenting program were asked to rate, on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all important) to 5 (extremely important), how important various factors (e.g., your partner suggested you attend the program) were in initially motivating them to attend the program, and an open-ended question about information they would like to have included in the program.

Program Content, Features, and Delivery Preferences

Fathers rated the importance of including 13 specified topics (see Table 2 for the list of topics) in a parenting program, such as managing difficult child behavior, and building a positive relationship, using 5-point Likert scales from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). These topics were developed specifically for this survey. Program delivery methods that fathers would find useful were explored using father ratings of 16 delivery modes (see Table 3 for the delivery options), such as delivery over the internet or in a group format. Ten of the items were based on a questionnaire used by Morawska et al. (2011). The remaining six items, such as father-only group and weekend intensive, were added given their potential relevance for fathers. Ratings were made on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all useful) to 10 (extremely useful). Lastly, fathers were asked to rate the extent to which seven specified program features (drawn from Sanders et al. 2011a, b), may influence their decision to participate (such as, participants are able to set their own goals). A further five items of potential relevance to fathers were added; program content is tailored specifically to fathers, a male practitioner conducts the program, the program is free or low cost, the program is held in a convenient location, and extended family are able to attend (see Table 4 for the full list of features). Ratings were made using 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1(no influence) to 5 (a lot of influence).

Focus Groups

Focus group discussion topics included content that fathers would like to have incorporated in parenting programs, whether specific program delivery features were likely to increase engagement (e.g., facilitator gender, being able to share personal experiences), and ideas for recruiting and retaining fathers in programs (e.g., the wording of advertisements that might attract fathers and incentives to maintain attendance at program sessions). The discussion questions about program and delivery content were used to supplement and build on the survey data.

Procedure

Ethical approval was simultaneously obtained for both the survey and focus group from the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (21/6/2010). Participants were recruited using print and online advertisements distributed to community outlets, such as early childhood education centres, libraries, and local newspapers.

The survey was completed anonymously either online or in hardcopy format. Three separate focus groups were conducted with five fathers in each; two with fathers who responded to an advertisement and one with fathers from a family support centre. The focus groups were conducted as part of a study investigating the acceptability of an existing parenting program, however only the data on father engagement is reported in this paper. At the end of the focus groups fathers were each given a $20 petrol voucher to thank them for their time.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented for father program preferences in Tables 2, 3, and 4. Between 10 and 15 % of the fathers did not answer all of the questions, so the N for each question varies and is shown in the tables. Spearman’s Rho correlations were used to identify relationships between father preference variables, family demographic factors, child behavior difficulties, parenting confidence and perceptions, level of parenting support, and paternal stress and depression, with missing data excluded list-wise. Due to the large number of comparisons, a Holm-Bonferroni method was used to control the risk of family-wise type one errors when determining the significance of correlations. For the purpose of the correlations, ratings of child difficulties across all four areas (behavior, emotions, concentration and social) were standardized into one variable representing fathers’ level of concern. The only exception was for the correlations with parenting confidence variables, where items relating to confidence handling conduct problems were examined in relation to father ratings of child behavior difficulties and items relating to confidence handling child emotional problems were examined in relation to father ratings of child emotional difficulties.

Focus group discussions were transcribed and analyzed using an inductive approach as outlined in Thomas (2006). The transcripts were read multiple times and meaningful statements were extracted and used to create categories (e.g., program delivery, engaging fathers), with similar statements grouped together in the same category. The statements within each category were then further defined into sub-themes (e.g., the use of humor, the use of father friendly messages), with some statements being classified into more than one theme. Clarity of the themes was established by a second coder reading through the transcript statements in each category and coding them into the pre-determined themes, resulting in inter-rater reliability of 99 % agreement.

Results

Father Ratings of Child Behavior, Parenting Confidence, Perception of Parenting Roles, Parent Adjustment, and Parent Support

Table 1 shows that between 41 and 68 % of fathers reported that their child had no difficulties in any of the four areas (behavior, emotions, concentration or social). A smaller number of fathers (between 28 and 54 %) reported that their child had minor difficulties, with 3–9 % reporting definite difficulties and 1–3 % reporting severe difficulties in one or more areas.

Although many fathers (between 61 and 75 %) expressed high levels of confidence when dealing with their child’s behavior and emotions, between 22 and 27 % of fathers reported only moderate levels of confidence in dealing with behaviors such as, whining, seeking attention and emotional problems. The areas in which fathers were least confident included dealing with their child when s/he was unhappy (11 % rated ‘not at all’ or ‘a little’ confident), anxious (8 % rated ‘not at all’ or ‘a little’ confident), refusing to do as they are told (8 % rated ‘not at all’ or ‘a little’ confident), or misbehaving in public (9 % rated ‘not at all’ or ‘a little’ confident).

With regards to perceptions of positive and negative aspects of their parenting role 82 % of fathers reported parenting as being very or extremely rewarding and fulfilling. Seventy-two percent rated parenting as being very or extremely demanding, while 22 % of fathers rated parenting as being very or extremely stressful and depressing. When asked about their own stress and feelings of depression, 19 % (n = 30) of fathers reported feeling very or extremely stressed during the past month, with a further 44 % (n = 68) experiencing moderate stress levels. A smaller number of fathers reported feeling depressed over the past month, with 4 % (n = 6) rating themselves as very or extremely and 18 % (n = 28) rating themselves as moderately depressed. The remaining fathers reported feeling either not at all, or slightly stressed and depressed. As stress and depression ratings were moderately correlated (r = .47, p < .001) a composite rating of paternal stress and depression was created using the average of the two scores, which was used in subsequent analyses.

Relationships Between Father Ratings of Child Behavior, Parenting Experiences, and Parent Stress and Depression

Fathers who reported behavior difficulties with their child were less confident in dealing with parenting situations such as whining (r = −.32, p < .001), non-compliance (r = −.30, p < .001), and misbehavior (r = −.26, p = .002). Fathers who reported emotional difficulties with their child were less confident in dealing with parenting situations, such as their child feeling sad (r = −.32, p < .001) and worried (r = −.25, p = .002). Fathers who reported that their child had difficulties in one or more area (behavioral, emotional and/or social difficulties) were also more likely to report more negative experiences of parenting, specifically in response to the question ‘parenting is depressing’ (r = .23, p = .004), and were more likely to have higher levels of stress and depression (r = .25, p = .002). Fathers who rated themselves as having increased stress and depression were also more likely to report lower levels of confidence when dealing with children’s emotions, being worried, sad, or anxious, (r = −.23, p = .005 to r = −.24, p = .003) and behaviors, such as whining, seeking attention, non-compliance, and misbehaving in public (r = −.17, p = 0.037 to r = −.30, p < .001). Fathers with higher levels of stress and depression also had more negative perceptions of parenting, (i.e. parenting is depressing (r = .41, p < .001), stressful (r = .45, p < .001), and demanding (r = .27, p < .001).

Knowledge and Experience of Parenting Programs

Fathers’ knowledge and experience with parenting programs was low, with only 13 % reporting that they had heard of at least one of the available programs and only 3 % having ever attended a program. The most important reasons given for having attended a program were: to improve the relationship with their child, to develop a new skill, to seek advice on a range of issues, and to effectively manage child behavior.

Fathers’ Program Topic Preferences

Table 2 shows mean father preference ratings for specific topics they considered important to include in a parenting program. The topics rated as most important were; building a positive parent–child relationship, increasing children’s confidence and social skills, and the importance of fathers to children’s development. Fathers with lower levels of education were more likely to teaching children financial skills (r = −.26, p = .002) as an important topic to include in a parenting program.

Discussions from two of the focus groups provided further insight into fathers’ preferences for program content. Eight out of ten fathers were in favour of focusing on parenting tasks that fathers are typically involved in such as bed time, bath time and discipline, and areas they felt less confident in, such as showing physical affection to their children. The views expressed by one focus group were that fathers needed more guidance than mothers about ways to demonstrate physical affection, as illustrated by the following quote: “I think women don’t have any trouble with touching, hugging, kissing kids, that’s probably something that should specifically be targeted at fathers, with the appropriate behavior there”. All five of the fathers in one group wanted to learn techniques for controlling their negative emotional responses, so that they could discipline their child in a calm and effective way. As one father said, “Equipping the parents with their own monitoring systems, it’s always about the kids focus but not about the parent actually not losing their rag”. Three out of five fathers in another group were interested in how to balance work and family. All fathers with partners thought it was important to include information about how to work together with their partner, how to model the correct behavior as parents and the importance of consistency between parents, such as “backing each other up and not contradicting”.

Fathers’ Program Delivery Preferences

As shown in Table 3, delivery methods considered most useful by fathers were seminar, father only group, television series, web-based, and individually-tailored instruction. Out of the 14 delivery options, 14 % of fathers rated eight or more of the options highly (7 or more out of 10), 21 % rated only one or two options highly, and 9 % rated none of the options highly. Fathers who reported higher levels of stress and depression were more likely to rate the delivery options of self-directed with (r = .24, p = .004), and without (r = .28, p < .001) telephone assistance, and individually-tailored (i.e. meeting individually with a clinician to tailor the program to their needs) (r = .26, p = .002) as being useful.

In contrast to the survey responses most (14/15) of the focus group fathers stated they would not participate in a web-based program, as it would be similar to their work environment, take too long, or would be less motivating than leaving the house to attend a program. When asked whether the fathers would prefer to attend a father-only program or a program together with their partner, all of the fathers who were parenting with a partner stated that they would prefer for both parents to attend the program. Three of these fathers were also interested in attending a father-only group, and highlighted limitations of two parents attending, such as finding childcare, perceptions that mothers would control the conversation and whether parents would be willing to share openly with their partner in the room.

Program Features Influencing Father Engagement

Table 4 illustrates ratings of how much influence specific program features would have on fathers’ decisions to participate in a parenting program. Demonstrated program effectiveness was the most influential program feature, followed by program location, having a trained practitioner run the program and having a program that addresses issues of relevance to them. Fathers with higher levels of education were less likely to value the option of having extended family attend (r = −.23, p = .005). Fathers who reported high levels of stress and depression were more likely to value programs that are tailored to individual needs (r = .29, p < .001). Both survey and focus group fathers did not view a male facilitator as a factor that would influence their attendance, however, all of the focus group fathers agreed that if it was a father only group, a male facilitator would be preferable. The fathers in one focus group discussed a preference for learning the material through practical activities, as one father said, “It has to be interactive it can’t just be one guy talking”. Fathers across all three groups stated that they would like the opportunity to share personal experiences with other parents within the group to normalise the situation (i.e., realise they are experiencing similar issues), create a more casual environment, and learn from others as well as pass on knowledge.

Fathers’ Opinions About Increasing Attendance and Involvement

Focus group fathers’ views on how a program could be advertised so they would find it interesting and engaging were categorised into five sub-themes; the use of humour; the use of father friendly messages, such as, “Supercharging the dad you are”; using the child’s mother or large organisations to spread the message; focus on enhancing the child, “If it was about my kid, so the hook is there, if there is something that someone can teach me about my kid but I am learning at the same time”; and not implying that the fathers are doing a bad job, “They don’t need to be made to feel like there is a problem that needs fixing to come along, because most people shy away from that”. Fathers in one group thought that advertisements describing the focus of each session and what parent participation involved would increase the likelihood of fathers attending the program. Finally, fathers were asked about possible incentives that would encourage them to keep attending the sessions each week. None of the fathers felt that a material incentive was necessary as the intrinsic motivation of doing something for their children was enough. A common view expressed was that a material incentive would take the focus away from the purpose of the program, as this quote illustrates, “If you have to entice someone, how much effort are they putting in”. Most fathers thought that it was essential to provide snacks and beverages during sessions.

Discussion

This study is one of only a few community surveys of fathers’ parenting support needs and preferences for parenting program features and delivery methods. The present study has several advantages over previous research. First, unique aspects of the survey findings include data on program content preferences, program features and delivery methods relevant to fathers, and fathers’ levels of confidence in dealing with specific child behaviors and emotions. New information is also provided about the influence of factors such as, father education, child behavior difficulty, and father stress and depression on fathers’ program content and delivery preferences. Finally, new insights were gained from focus group participants about messages to include in program advertisements and program content to emphasise in order to engage fathers.

The percentage of fathers reporting child behavior problems in this sample was higher than the rates reported by Sanders et al. (2010) in which 3 % of fathers said their child’s behavior was very or extremely difficult. This may be partly due to differences in the number and wording of the rating scale anchor points between the two studies. In the present study fathers were asked to make separate ratings about perceived child behavior and emotional problems, whereas in the study by Sanders et al. fathers’ perceptions of child emotional or behavioral problems were combined into one question. It was noteworthy, that 10 % of fathers in our study considered their child to have definite or severe emotional problems. As with previous research (Dave’ et al. 2008; Sanders et al. 2010) we found a positive relationship between father ratings of child behavior difficulties and father stress, as well as negative perceptions of parenting. However, unlike Sanders et al. (2010) we found no relation between father perceptions of child behavior problems and father education. The reason for this difference could be that compared to Sanders et al. our study had a much smaller sample size and the majority of fathers were well educated. The percentage of fathers reporting feeling very or extremely stressed in our study was slightly higher than that found by Sanders et al. (2010), which may have been due to differences in other sample characteristics across the two studies.

Our findings for preferred program features are similar to those obtained in the UK web-based survey of working parents by Sanders et al. (2011a, b) who also found the most preferred features for fathers were program effectiveness, trained practitioners and content being personally relevant. Thus, the results suggest that the desire for high quality, content relevant programs that work is common to fathers cross-nationally.

There are some similarities between program delivery preferences obtained for fathers in this study (seminar, father-only group, television series, and web-based delivery) and data collected from Australian parents from culturally-diverse backgrounds (Morawska et al. 2011) and from an ethnically-diverse sample of parents in the USA (Metzler et al. 2012). In all three studies, television and seminar were among the top four preferred delivery methods. Like parents in the Metzler et al. study, fathers in the current survey also ranked internet delivery among the top four most preferred delivery methods. However, Morawska et al. and Metzler et al. did not separate out findings for mothers and fathers. Thus direct comparisons with father data across the three studies were not possible. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with other research that indicates a preference for less intensive delivery methods (Metzler et al. 2012; Morawska et al. 2011). Such preferences could be due to fathers’ limited free time to attend programs, practical considerations of organising childcare, or the desire to keep their parenting concerns private. The web-based preference may reflect parents’ increasing use of the internet to find solutions to various parenting problems without the need for face-to-face interaction. Given the variability in preferences it is important to offer a diverse range of delivery options in order to cater to a range of father needs and reduce barriers to father involvement. Furthermore, based on the pattern of preference ratings found in this study, (i.e., some fathers rating many options highly and other fathers rating none of the options highly) further research should investigate other factors that may influence father program delivery preferences.

The findings from this study have a number of implications for promoting parenting programs to fathers and for tailoring program content to fathers’ interests. The survey results show that only a very small number of fathers were aware of available parenting programs and an even smaller number had attended a program in the past, which underscores the need for better program promotion. Our results suggest that possible ways to achieve this would be to give fathers more specific information in advertisements about what is involved in participation, to highlight program content likely to be of interest to fathers, and to mention that the program is run by trained practitioners. Advertisements should convey messages about optimising outcomes for children rather than fixing child behavior and family problems, or parental shortcomings. As many fathers were particularly interested in whether the program had a strong evidence base, this information could be included in advertisements to help parents differentiate between evidence-based techniques and other information that is widely available.

With regards to program content, our findings suggest that many fathers would like to learn about building positive relationships with their children, optimising their child’s development in areas such as self-confidence and social skills, and the contribution fathers make to their child’s development. The importance of fathers could be incorporated into a program by providing content based on empirical evidence in a way that is understandable to parents. An example of incorporating program content to increase children social skills is provided by Frank et al. (2014) who highlighted how fathers’ and mothers’ interactions with their children provide models for interactions with peers, and incorporated a practical example of teaching children problem-solving skills into program content. Finally the finding that between eight and 10 % fathers were not confident when dealing with their children’s unhappiness and anxiety suggests that the practitioners might need to incorporate program content for enabling some fathers to manage emotional as well as behavioral difficulties.

Many of the topics suggested by the focus group fathers are already covered in parenting programs based on social learning principles (e.g., how to deal with bedtime, discipline strategies, show affection, and the importance of consistency between parents) however, they do indicate a number of specific areas where extra content for fathers might be helpful. For example, Frank et al. (2014) incorporated focus group suggestions from this study into program content by providing a range of examples of how fathers and mothers could demonstrate physical affection (e.g., rough and tumble play, high fives), and various strategies that parents could use at home or in public to help them keep calm when disciplining their child. An emphasis on stress management techniques when managing child behavior also seems warranted given the high numbers of fathers in the study who reported that parenting is demanding and stressful, and given the relationship found between father perceptions of child behavior difficulties and father reported personal stress, lower levels of parenting confidence and negative perceptions of parenting. Including information on techniques for managing personal stress may also be important. For example, findings from Sanders et al. (2011a, b) found that program content that included helping parents cope with the concurrent demands of work and family life was associated with lower levels of personal distress.

Fathers who reported higher levels of stress and depression also showed a preference for programs being tailored to meet individual needs. Previous research has demonstrated that paternal depression is significantly related to more negative parenting behaviors, similar to that seen with mothers, and an even greater decrease in positive parenting behaviors for fathers compared to mothers (Wilson and Durbin 2010). This research, together with our findings that these fathers reported more negative perceptions of parenting and less parenting confidence, highlights the need to include fathers experiencing stress or depression in parenting interventions that specifically address parent mental health.

Focus group findings suggested that developers should examine program content to ensure that it is meeting the needs and interests of both parents, and focus on how parents can work together to use the same strategies in various parenting situations. Research has shown that conflict over parenting decreases effective parenting practices and is related to higher levels of child problem behavior, and that parenting programs that promote a more positive co-parenting relationship will be more effective than those that do not (Cowan et al. 2010; Lee and Hunsley 2006).

Our findings also suggest that lighter touch parenting programs may be beneficial for some fathers, given the numbers who had some minor concerns with their children’s behavior and who reported only moderate levels of confidence in dealing with specific child behaviors. One-off discussion groups focusing on specific issues, such as handling emotional problems or disobedience, may better meet the needs of these fathers than an 8 week intensive course (Morawska et al. 2011).

There is disagreement in previous research as to whether having a male facilitator may increase father engagement (Berlyn et al. 2008; O’Brien and Rich 2003). Both the survey and focus group data presented here suggests that facilitator gender would have little impact on fathers’ initial and continued program engagement.

One limitation of this study was that the survey was not specifically conducted with fathers of children with behavior difficulties, who are most often targeted for inclusion in parenting interventions. However, if the goal is to increase the reach of parenting interventions via a public health approach, information is needed on the needs of many father groups, including those with mild concerns about child behavior and those with clinically elevated levels of behavior problems. By adapting programs based on father preferences and offering support with varying levels of practitioner involvement and delivery methods, we are more likely to increase the number of fathers who are receiving parenting support at a level that meets their needs. Another limitation of the survey is the relatively small sample size and disproportionate representation of fathers from higher socioeconomic backgrounds.

Future research could sample a larger, more representative and diverse group of fathers, that includes different cultural groups and other groups of fathers present in society. The focus groups also highlighted some possible items for inclusion in future survey work with fathers. For example, further questions about the importance of program topics such as, dealing with bed time, how to keep cool when disciplining your child, the co-parenting relationship, and how fathers can show physical affection; and questions about how to word advertisements to attract fathers.

In summary, the present study provides some baseline data regarding fathers’ parenting support needs and program preferences that can be used as starting point for adapting program content and delivery to better meet the needs of different father groups. Findings highlight program content that could be emphasized to increase father engagement and the range of delivery options that could be offered to meet a variety of father parenting support needs, including mild to moderate concerns about their child’s behavior and how to deal with specific behaviors and emotions, and supporting fathers who are experiencing elevated levels of personal and parenting stress.

References

Addis, M. E., & Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist, 58, 5–14. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.5.

Anderson, E. A., Kohler, J. K., & Letiecq, L. (2002). Low-income fathers and “responsible fatherhood” programs: A qualitative investigation of participants’ experiences. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 51, 148–155. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00148.x.

Atwood, R., Gold, M., & Taylor, R. (1989). Two types of delinquents and their institutional adjustment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57, 68–75.

Bagner, D. M., & Eyberg, S. M. (2003). Father involvement in parent training: When does it matter? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 599–605.

Berlyn, C., Wise, S., & Soriano, G. (2008). Engaging fathers in child and family services. Family Matters, 80, 37–42.

Bogels, S., & Phares, V. (2008). Fathers’ role in the etiology, prevention and treatment of child anxiety: A review and new model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 539–558. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.07.011.

Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2002). Interventions as tests of family systems theories: Marital and family relationships in children’s development and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 731–759. doi:10.1017/S0954579402004054.

Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., & Knox, V. (2010). Marriage and fatherhood programs. The Future of Children, 20, 205–230. doi:10.1353/foc. 2010.0000.

Dave′, S., Nazareth, I., Senior, R., & Sherr, L. (2008). A comparison of father and mother report of child behaviour on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 39, 399–413. doi:10.1007/s10578-008-0097-6.

Dretzke, J., Davenport, C., Frew, E., Barlow, J., Stewart-Brown, S., Bayliss, S., et al. (2009). The clinical effectiveness of different parenting programmes for children with conduct problems: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 3, 7. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-3-7.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., & Boggs, S. R. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 215–237. doi:10.1080/15374410701820117.

Fabiano, G. A. (2007). Father participation in behavioral parent training for ADHD: Review and recommendations for increasing inclusion and engagement. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 683–693. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.683.

Frank, T., Keown, L., & Sanders, M. (2014). An RCT of Group Triple P for fathers and mothers of children with conduct problems. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Goodman, S. H., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106, 458–490. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.106.3.458.

Hoff, E., Laursen, B., & Tardif, T. (2002). Socioeconomic status and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting. Biology and ecology of parenting (Vol. 2, pp. 231–252). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kirby, J. N., & Sanders, M. R. (2012). Using consumer input to tailor evidence-based parenting interventions to the needs of grandparents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 626–636. doi:10.1007/s10826-011-9514-8.

Knoster, C. (2003). Implications of childhood externalizing problems for young adults. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(4), 1073–1080.

Lazar, A., Sagi, A., & Fraser, M. W. (1991). Involving fathers in social services. Children and Youth Services Review, 13, 287–300. doi:10.1016/0190-7409(91)90065-P.

Lee, C. M., & Hunsley, J. (2006). Addressing coparenting in the delivery of psychological services to children. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 13, 53–61. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2005.05.001.

McLanahan, S., & Teitler, J. (1999). The consequences of father absence. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), Parenting and child development in “non-traditional” families (pp. 83–102). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associate Publishers.

Metzler, C. W., Sanders, M. R., Rusby, J. C., & Crowley, R. N. (2012). Using consumer preference information to increase the reach and impact of media-based parenting interventions in a public health approach to parenting support. Behavior Therapy, 43, 257–270. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2011.05.004.

Morawska, A., Sanders, M., Goadby, E., Headley, C., Hodge, L., McAuliffe, C., et al. (2011). Is the Triple-P Positive Parenting Program acceptable to parents from culturally diverse backgrounds? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20, 614–622. doi:10.1007/s10826-010-9436-x.

O’Brien, C., & Rich, K. (2003). Evaluation of the Men and Family Relationships Initiative: Final report and supplementary report. Balmain, New South Wales: Department of Family and Community Services.

Sanders, M. R. (2012). Development, evaluation and multinational dissemination of the Triple P-Positve Parenting Program. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8, 345–379. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143104.

Sanders, M. R., Dittman, C. K., Keown, L. J., Farruggia, S., & Rose, D. (2010). What are the parenting experiences of fathers? The use of household survey data to inform decisions about the delivery of evidence-based parenting interventions to fathers. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41, 562–581. doi:10.1007/s10578-010-0188-z.

Sanders, M. R., Haslam, D. M., Calam, R., Southwell, C., & Stallman, H. M. (2011a). Designing effective interventions for working parents: A web-based survey of parents in the UK workforce. Journal of Children’s Services, 6, 186–200. doi:10.1108/17466661111176042.

Sanders, M. R., & Kirby, J. N. (2011). Consumer engagement and the development, evaluation, and dissemination of evidence-based parenting programs. Behavior Therapy, 43, 236–250. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.005.

Sanders, M., Kirby, J., Tellegen, C., & Day, J. (2013). Towards a Public Health approach to parenting support: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Submitted for Publication.

Sanders, M. R., Stallman, H. M., & McHale, M. (2011b). Workplace Triple P: A controlled evaluation of a parenting intervention for working parents. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 581–590. doi:10.1037/a0024148.

Santucci, L. C., McHugh, K. R., & Barlow, D. H. (2011). Direct to consumer marketing of evidence-based psychological interventions. Behavior Therapy, 43, 231–235. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2011.07.003.

Statistics New Zealand. (2010). New Zealand income survey: June 2010 quarter. Wellington, New Zealand: Statistics New Zealand.

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27, 237–246. doi:10.1177/1098214005283748.

Tiano, J. D., & McNeil, C. B. (2005). The inclusion of fathers in behavioral parent training: A critical evaluation. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 27, 1–28. doi:10.1300/J019v27n04_01.

Webster-Stratton, C., & Hammond, M. (1997). Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: A comparison of child and parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65, 93–109.

Wilson, S., & Durbin, E. C. (2010). Effects of paternal depression on fathers’ parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 167–180. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frank, T.J., Keown, L.J., Dittman, C.K. et al. Using Father Preference Data to Increase Father Engagement in Evidence-Based Parenting Programs. J Child Fam Stud 24, 937–947 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9904-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-9904-9