Abstract

Participants were 933 fathers participating in a large-scale household survey of parenting practices in Queensland Australia. Although the majority of fathers reported having few problems with their children, a significant minority reported behavioral and emotional problems and 5% reported that their child showed a potentially problematic level of oppositional and defiant behavior. Reports of child problems were associated with fathers’ levels of personal stress and socioeconomic disadvantage. Approximately half of all fathers reported the use of one or more coercive parenting strategies (shouting and yelling, hitting the child with their hand or with an object) with fathers’ use of hitting being associated with child behavior difficulties. Fathers reported low rates of help seeking or participation in parenting courses, with socially disadvantaged fathers being less likely to complete parenting programs than other fathers. Implications for research on increasing fathers’ participation rates in parenting programs are discussed and directions for future research highlighted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

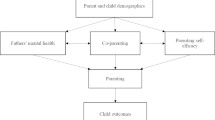

Behavioral family intervention (BFI) based on social learning principles [1] has been recommended as the first line approach for the treatment and prevention of disruptive behavior disorders in children [2, 3]. There is now an extensive evidence base that shows that BFI produces long-lasting improvements in conduct problems in children and in aspects of family functioning, including parenting styles and parental wellbeing [4, 5]. BFIs function by targeting those modifiable family risk and protective factors that have been shown to contribute to the development and maintenance of disruptive behavior in children, including coercive discipline practices, ineffective or inconsistent parenting strategies, parental adjustment, parenting confidence, and partner support in parenting [6–8].

Despite strong empirical support for the effectiveness of BFIs, the majority of trials do not include fathers [9, 10]. However, available research on fathers’ contribution to children’s behavioral development provides some key reasons why increased father involvement in BFI is likely to be beneficial [11, 12]. In particular, although there is growing evidence from studies of typically developing children that mothers and fathers influence their children in similar ways, evidence is also emerging that fathers make a unique contribution to their children’s behavioral and social development [12, 13].

For example, Isley et al. [14] found that fathers’ level of affect and control predicted children’s social adaptation with peers after maternal effects were controlled. Similarly, in a study of 994 families from the US National Survey of Families and Households, Amato and Rivera [15] found that fathers’ positive involvement, as reflected in shared activities (meals, play, homework) and supportive behavior (praise, physical affection), was associated with fewer behavior problems in children, independently of mothers’ parenting. Other longitudinal data indicate that paternal sensitivity contributes uniquely to young children’s behavioral and social competence outside the family, when maternal effects are accounted for [16].

Moreover, although far less attention is paid to fathers relative to mothers in the developmental psychopathology literature [10], there is building evidence that fathers influence child mental health outcomes, particularly in relation to externalising or disruptive behavior problems [13]. For example, cross sectional studies of fathering indicate that preschool behavior problems are associated with lower rates of parenting satisfaction, more overactive, less authoritative parenting strategies [17], a lower sense of parenting efficacy [18], greater use of corporal and verbal punishment [19], more negative interactions [20], less responsive interactions [17], and less positive involvement with their sons [21]. Conversely, longitudinal findings show that positive paternal behaviors, including observed proactive parenting and lack of reported hostility and anger are related to improved outcomes in preschool children at high risk of developing disruptive behavior problems [22].

Findings from a small number of studies also highlight other paternal risk factors for the development of disruptive behaviors in children. There is evidence to suggest that paternal psychological functioning, including depression and stress, is associated with externalising child behavior problems that can originate very early in development [23–26]. For example, a recent large-scale longitudinal population study in the UK found that children of fathers who were postnatally depressed had an increased risk of conduct problems and hyperactivity at age 3.5, even after controlling for maternal depression and socioeconomic factors [27]. There is also support from another longitudinal study in the US for bi-directional influences between paternal depression and child behavioral and emotional problems [28].

The association between less optimal marital or couple functioning and negative child outcomes is well-established [29, 30]. Marital conflict has been found to undermine effective parenting practices [31–33]. Parents are more likely to report difficult child behavior if there are low levels of partner support and high levels of disagreement reported by partners [34]. This relationship between marital relationship problems, parenting quality, and child behavior difficulties has been found for both mothers and fathers [35–37], with the spillover of marital discord into fathering difficulties being just as likely as it is for mothers [38].

Taken together, this evidence suggests that fathers play an important and potentially unique role in children’s behavioral development. However, much of this evidence is based on small, clinically referred samples and very few studies have provided a systematic investigation of the parenting experiences of an unselected population sample of fathers with a focus on those factors that are associated with disruptive behavior. There is clearly room for further large-scale research regarding fathering factors that contribute to the development of disruptive behavior disorders in children. Specifically, epidemiological research is needed to obtain information about father reports of the prevalence of targeted child behavior problems (e.g., disruptive behavior or conduct problems) as well as associated paternal risk (e.g., inconsistent or coercive parenting, paternal stress and depression) and protective factors (e.g., positive and effective parenting strategies, participation in parenting programs). Data of this kind can be used to inform decisions about the need to include fathers in research on BFIs and to identify the groups of fathers that would most benefit from this type of support.

The current study used data on fathers taken from a large population survey of child behavior problems and parenting practices that were obtained via computer assisted telephone interviews (CATI) of primary caregivers living in Queensland, Australia. This study aims to describe the parenting experiences of fathers by reporting: (1) the prevalence and severity of disruptive behavior problems, specifically symptoms of Oppositional Defiant Disorder; (2) the prevalence of the use of effective and ineffective parenting strategies; and (3) the prevalence of other modifiable risk (i.e., father stress and depression) and protective factors (i.e., partner support and agreement over parenting; father help-seeking behavior). We were also interested in identifying those factors, including perceptions of the parenting role and socio-demographic variables, that were associated with fathers’ reports of child behavior risk and the use of inappropriate discipline strategies.

Method

Participants

The participants were 933 males living in Queensland, Australia who self-identified as the primary caregiver of at least one child aged 0–12 years. As over 98% of the respondents were the target child’s biological or adoptive father, the term ‘parent’ or ‘father’ will be used instead of ‘caregiver’ for the remainder of this paper. Details of the exclusion criteria have been described elsewhere [39]. Briefly, fathers were not eligible to participate if they were less than 18 years of age; they did not have a child in the targeted age range; they did not speak English sufficiently well or had a mental or physical disability that precluded them from taking part in a telephone survey; or they were staying in the contacted household, but did not live there permanently. Fathers who had more than one child aged under 12 were asked to respond in relation to their eldest child and to answer all child-oriented questions in relation to this child only.

Measures

A structured interview was specifically designed for the survey to assess the following aspects of the parenting experience of fathers. Full details are provided in Sanders et al. [39].

Socio-Demographic Variables

To establish the extent to which parenting and child behavior problems were related to adverse socio-economic circumstances, a range of socio-demographic information was collected, including the age and sex of children and age of fathers, respondent’s employment status, respondent’s education levels, respondent’s marital status, whether the family resided in a metropolitan, urban or rural area, annual household income and respondent’s ethnic background. These socio-demographic items, chosen for inclusion by the Health Information Centre, are based on a standard set of socio-demographic questions used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Assessment of Child Behavioral and Emotional Problems

This was assessed by a series of questions that asked fathers to report on their perceptions of their child’s behavior. Fathers were asked whether they considered their child had any emotional or behavioral problems over the past 6 months (yes, no). Fathers were then asked to use a Likert scale to rate how difficult their child’s behavior had been over the past 6 months (1 = not at all, 2 = slightly, 3 = moderately, 4 = very, 5 = extremely). These questions constituted global measures of child functioning that had been used in the Western Australia Child Health Survey [40] and shown to be related to independent reports of behavior difficulties in children by teachers.

We were particularly interested in the extent of conduct-related problems. Parents with children aged 2 years or more were asked to indicate how often (1 = not at all, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, 4 = very often) their child had engaged in any of eight specific types of conduct problems over the last 6 months. These items were taken from the list of symptoms specified under Criteria A in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ [41] diagnostic criteria for ODD. Specifically, these behaviors were: losing temper; arguing with adults; defying/refusing to cooperate with adults; deliberately annoying people; blaming others for their mistakes; being touchy or easily annoyed by others; being angry or resentful; and being spiteful and vindictive. Internal consistency of this symptom checklist in the current sample of fathers was α = .68. Responses to these questions were used to gain an estimate of the prevalence of patterns of oppositional and defiant behavior in children in this sample. Children were classified as showing potential ODD when a father reported that their child had often or very often engaged in four or more of these behaviors in the last 6 months (as with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria) [46].

Assessment of Family Factors

Specific Parenting Practices

Fathers with children aged 2 years or more were asked about their use of parenting strategies for encouraging desirable behavior and dealing with misbehavior. The parenting strategies for encouraging desirable behavior included: praising the child by describing what was pleasing, giving a treat, reward or fun activity, or giving attention such as hug or wink when the child engaged in desirable behavior. Strategies for dealing with misbehavior were divided into two groups. The first set of five strategies have been shown to be effective in managing misbehavior, and included: ignore the problem behavior, tell the child to stop misbehaving, use a consequence that fits the situation, send the child to quiet time or timeout and call a family meeting to work out a solution. The second set of strategies have been associated with coercive or ineffective discipline, and included: single smack with hand, smack more than once with hand or with an object other than hand, and shout or become angry. These two measures of parenting strategies were derived from an extensive scientific body of research that has identified specific parenting practices related to pro-social and deviant outcomes for children [1].

With regard to encouraging desirable behavior, fathers were asked to consider how likely they were to use each of the three parenting strategies when their child behaves well or does things that please them. For each of the ten parenting strategies for managing misbehavior, fathers were asked to consider how likely they were to use each of the ten strategies when their child really misbehaves. A 5-point Likert scale was used for each parenting strategy (1 = very unlikely through to 5 = very likely).

Parents’ Perceptions of the Positive and Negative Aspects of Their Parenting Roles

We also examined fathers’ perceptions of some positive and negative aspects of the parenting experience. Fathers were asked to rate the extent to which they perceived parenting to be rewarding, fulfilling, demanding, stressful and depressing. Five-point Likert scales were used (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely).

Parental Adjustment

Fathers rated how stressed and how depressed they had felt over the 2-week period prior to the survey on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely).

Parental Self-Efficacy

Fathers were also asked how confident they had felt in the last 6 months to undertake their responsibilities as a parent to their child aged 12 years or less. This single item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). Parental self-efficacy was measured as it is a construct highlighted in the developmental psychology literature as a mediator of developmental outcomes in children [42, 43].

Help-Seeking Behavior and Participation in Parenting Programs

To assess the extent to which fathers seek professional assistance for behavioral and emotional problems in children, they were asked a series of questions about what parenting programs they had completed or professionals they had seen. These included whether they had seen a professional about their child’s behavior in the past 12 months (yes, no) and, if so, what sort of professional they had seen (open-ended response); and whether they had participated in any parent education program or parenting course in the 12 months prior to the survey (yes, no). These items were generated to represent indices of active parental coping strategies [44].

Parental Social Support

To assess the availability of practical and emotional support for fathers, respondents were asked whether they lived with a partner (yes, no). Those respondents living with a partner at the time of the survey were also asked: (1) the extent to which they and their partner agree about methods of disciplining their child (1 = not at all, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = usually, 5 = always); and (2) how supportive their partner had been towards them in their role as a parent in the last 6 months (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). These items were generated to represent indices of parental coping resources [44].

Survey Procedure

Full details of the survey methods are described in Sanders et al. [39]. The CATI methodology is used routinely by government agencies around the world, including Queensland Health, to collect surveillance data on health behaviors and practices in the community [45]. Interviews were conducted by trained telephone interviewers and a supervisor employed by Queensland Health using the Health Information Centre CATI system. To maintain consistency and ensure high quality interview standards, interviewers were instructed to read the questions exactly as seen on the computer screen and a random selection of calls were monitored. A random sample of private households in Queensland (a north-eastern state of Australia with approximately four million residents) was contacted. Interviewers asked to talk to the principal caregiver where a household was found to have at least one child aged 12 years or less. Brief information on the nature of the survey was then provided to fathers and verbal consent was obtained before beginning the interview. A simple random sample of listed private telephone numbers was drawn from a database of all listed private numbers in Queensland. This was supplemented with a random sample of non-listed (silent) numbers in the Brisbane and Gold Coast area of Queensland. The scheme produced a sample of telephone numbers that included, as a subset, a good approximation to a simple random sample of households with a fixed telephone. Around 4% small proportion of the target population was excluded from selection because their household did not have a fixed telephone.

Consistent with previous surveys of disciplinary practices [45], procedures to preserve the anonymity of respondents were implemented to eliminate response biases to questions that asked about potentially sensitive and high-risk parenting behaviors. With the exception of telephone numbers, no identifying information about fathers or their families was obtained or recorded. A separate database of telephone numbers, which was accessed only by trained CATI survey staff and not by the researchers, was kept so that fathers could be re-contacted in the event that they did not answer or were unable to talk at the time of the call. Numbers were purged from the system once contact was made so that numbers were not matched to individual sets of data at any point during the data collection process. Ethical approval was obtained for the project from the first author’s University Human Ethics Committee as well as the Queensland Health Department.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of Father Sample

A total of 933 fathers completed the parenting telephone interview, which represented a response rate of 82% of fathers who were eligible. Table 1 reports the demographic characteristics of the sample. Most fathers in the sample were the target child’s biological or adoptive parent, were aged between 30 and 49 years (mean age = 38.68 years), were married and worked full-time. The majority of fathers had completed a post-secondary school qualification, lived in a city or urban area, and had a combined household income between $25,000 and $100,000. Target children ranged in age from 0 to 12 years (mean age = 6.37 years), and 54% of the children were male.

Statistical Analyses

Participants with children aged less than 2 years of age (n = 133) were not asked questions about the extent of conduct-related problems or about their use of parenting strategies to encourage desirable behavior or respond to misbehavior. Consequently, analyses involving these variables were based only on those parents with children aged between 2 and 12 years. Similarly, analyses involving the extent of partner support or partner agreement about discipline included only those parents who indicated that they lived with a partner.

Because there was a negligible proportion of missing values (<1%) across each question, all cases with missing data were removed from the data set before analyses were conducted. The only exception to this listwise deletion of cases with missing data were the approximately 7% of respondents who did not know or were unwilling to report their household income. Thus, unless otherwise indicated, analyses on all children were based on N = 882, while analyses on children aged between 2 and 12 years involved N = 755.

A series of chi square analyses were conducted to assess bivariate associations between the categorical variables. Included in these analyses were the father and child demographic variables, child behavior variables, parenting perception variables, parental confidence, partner agreement and support, and father stress. To allow for the evaluation of odds ratios, all categorical variables were dichotomised. Details of dichotomisation are reported in the appropriate section below.

Multivariate logistic regression was then used to determine the optimal predictors of child behavior difficulty, potential ODD diagnosis, and coercive parenting strategies. Predictors that were significant at the bivariate level were entered into a standard logistic regression to determine their predictive power. A backward elimination procedure was then used to construct a ‘best’ or most parsimonious model. For all analyses, results are presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

An alpha level of .05 was used for all statistical tests. Actual p values have been reported to highlight interesting findings and trends [46]. However, given the number of outcome variables assessed and the increased probability of making a Type 1 error, caution should be exercised when interpreting the findings.

Child Behavior Difficulty

Most fathers reported that their child’s behavior over the past 6 months was not at all, slightly, or moderately difficult (97%), with just under 3% of fathers rating their child’s behavior as very or extremely difficult. Bivariate analyses indicated that fathers who thought that their child’s behavior was very or extremely difficult were less likely than those who thought that their child’s behavior was not at all, slightly, or moderately difficult to be in paid employment and to have completed secondary school (see Table 2). Fathers who reported having difficult children perceived parenting to be more demanding, stressful, and depressing, and less rewarding. These fathers were also more likely to report that they had been very or extremely stressed in the past 2 weeks.

The variables that were found to be significantly associated with father reports of child behavior difficulty at the bivariate level were entered simultaneously into a logistic regression analysis. Of those variables significant at a bivariate level, only employment status, education level, child behavior or emotional problems, potential ODD diagnosis, and father stress were significant multivariate predictors. When the logistic regression was repeated using these significant multivariate predictors, the optimal model for predicting difficulty of child behavior comprised employment status, child behavior or emotional problems, potential ODD diagnosis, and father stress (see Table 2).

Prevalence and Correlates of Oppositional Behavior Problems

Approximately a quarter of all fathers reported that their child had experienced a behavioral or emotional problem in the 6 months prior to the telephone survey. Most fathers (62%) reported that their child did not experience problems with any of the symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) over the past 6 months, while 21% reported that their child often or very often displayed one of these symptoms. Around 5% of these children showed elevated levels of ODD by father report, defined as ratings of often or very often on four or more ODD symptoms. For each of the eight symptoms of ODD, the proportion of fathers that reported that their child engaged in these behaviors often or very often is displayed in Fig. 1.

Bivariate analyses indicated that fathers who rated their child as having a potential ODD diagnosis were less likely to be in paid employment and were more likely to have a low household income (see Table 3). These fathers viewed parenting as less rewarding and more demanding and stressful, and had lower confidence in their parenting skills. Father-reported potential ODD diagnosis was also associated with lower levels of partner support for parenting and higher levels of stress and depression. Of these variables, only household income, child behavior difficulty, and parenting is demanding were significant in a logistic regression analysis. These variables also made up the best and simplest model (see Table 3).

Strategies for Encouraging Appropriate Behavior

Fathers of 2–12-year-old children were asked about their use of three strategies that have been shown to encourage desirable behavior. Figure 2 displays fathers’ use of strategies when their child behaved well. Fathers were highly likely to use these strategies, as 82% of fathers reported that they were likely or very likely to use all three strategies.

Strategies for Dealing with Misbehavior

Fathers whose target child was between the ages of two and 12 rated the likelihood that they would use a number of strategies for dealing with their child’s misbehavior. The likelihood that fathers would use each of the strategies is displayed in Fig. 2. Around 82% of fathers reported that they were likely or very likely to use two or more of the four strategies that have been shown to be effective in managing misbehavior. However, a large proportion of fathers reported also using less optimal strategies, including shouting or becoming angry, giving the child a single smack, and smacking the child more than once or with an object other than their hand. Approximately 43% of fathers reported using one of these less effective strategies, 29% reported using two, and just under 5% reported that they used all three strategies.

Chi square analyses were conducted to examine those child and father factors that were associated with fathers’ use of each of the less effective strategies (see Table 4). Fathers who stated that they were likely or very likely to shout or become angry at their child were more likely to have a child with a potential ODD diagnosis and to report low agreement with their partner over parenting issues. These fathers also rated parenting as being less rewarding and more demanding and stressful than fathers who did not use this strategy frequently. When these variables were entered into a simultaneous regression model, only the response that parenting is demanding was significantly related to the use of less effective parenting strategies.

The 42% of fathers who reported that they were likely or very likely to give their child a smack with their hand were more likely to have a child who was male and whom they rated as showing very or extremely difficult behavior (see Table 4). Fathers who reported smacking their child were more likely to perceive parenting as stressful and demanding, and to report low support from their partner. In multivariate analyses, child behavior difficulty was the only significant predictor of fathers’ use of a single smack as a discipline strategy.

Around 7% of fathers reported that they were likely or very likely to smack their child more than once or with an object other than their hand. Fathers’ use of this discipline strategy was associated with all three measures of problematic child behavior. Compared to fathers who reported that it was unlikely that they would use this strategy, these fathers were more likely to rate their child’s behavior as very or extremely difficult, to indicate that their child showed elevated levels of ODD symptoms, and to report that their child experienced a behavioral or emotional problem in the past 6 months (see Table 4). They also tended to view parenting as less rewarding and more demanding, stressful, and depressing. Multivariate regression analyses indicated that child behavior difficulty and parenting is stressful were the best predictors of fathers’ likelihood of smacking their child more than once or using an object.

Father Wellbeing

Fourteen percent of fathers reported that they were very or extremely stressed in the 2 weeks prior to the survey, with the remainder (86%) reporting that they were not at all, slightly, or moderately stressed. A small proportion of fathers (2%) reported that they were very or extremely depressed, with 98% reporting that they were not at all, slightly, or moderately depressed.

Relationship Adjustment

Most fathers (92%) indicated that they had a partner. Six percent of these fathers indicated their partner was not at all, slightly, or moderately supportive in their role as a parent and 7% reported that they and their partner not at all, rarely, or sometimes agreed about methods of disciplining their child.

For fathers, low levels of partner support were associated with the father not being in paid employment and having a child who was school-aged and male (see Table 5). Fathers reporting low levels of partner support were more likely to have a child with a behavioral or emotional problem or a potential ODD diagnosis. These fathers viewed parenting as less rewarding and fulfilling, and more stressful and depressing. Fathers reporting low levels of partner support were less confident in their parenting skills, tended to agree with their partner less over child discipline issues, and were more likely to be stressed and depressed. Similarly, low levels of partner agreement about child management was associated with father unemployment, low parenting confidence, child behavior or emotional problems, perceptions that parenting is stressful, not rewarding or fulfilling, and father depression.

Help Seeking

Around 6% of fathers reported that they had consulted a professional about their child’s behavior in the past 6 months. The most frequently consulted professionals included teachers, general practitioners, and psychologists. A slightly larger proportion (11%) of fathers had participated in a parent education program. Of those fathers who indicated that their child had experienced behavior or emotional problems in the past 6 months, 20% had sought professional help and 13% had completed a parenting program.

Fathers who had seen a professional in the past 6 months were less likely to be in paid employment, and more likely to be single and to have not completed secondary school (see Table 6). The children of fathers who had sought help from a professional tended to be at school and to be rated by their father as showing high levels of difficult behavior, having a behavioral or emotional problem, and having a potential diagnosis of ODD. These fathers viewed parenting as more stressful and depressing and less rewarding than fathers who had not sought outside professional help, and they also had higher levels of stress. Participation in a parent education program was associated with higher household income, completion of secondary school, more difficult child behavior, higher levels of partner support and greater stress (see Table 6).

Discussion

The present study provides descriptive information regarding the experiences of fathers in their parenting role. Overall, fathers found the parenting role a rewarding and enjoyable experience, considered themselves well supported by their partners, and the majority indicated their children did not have any major behavior or emotional problems. Notwithstanding the generally positive parenting experiences of the majority of fathers, a significant minority (25%) reported that their child had experienced behavioral and emotional problems in past 6 months, with 5% reporting their child showed potentially clinically elevated levels of ODD symptoms, and 3% of fathers considering their child’s behavior to be very or extremely difficult. These are slightly lower rates of clinically elevated symptoms of ODD than those obtained in community samples comprising both mothers and fathers [39, 47] but comparable to rates of ODD obtained in Australia’s National Mental Health Survey of Children and Adolescents [48].

The second aim of this study was to describe the prevalence of fathers’ use of strategies to promote desirable behavior and manage misbehavior. It was encouraging to note that the majority of fathers reported using positive parenting techniques such as giving positive attention, praising their children and giving physical affection to encourage appropriate behavior in their child. Moreover, fathers reported using strategies that have been identified as effective in managing misbehavior, with telling their child to stop the behavior and ignoring the problem behavior the two most commonly used strategies. Strategies such as these are recommended by most evidence-based parenting programs that aim to promote socially acceptable behavior and to reduce the occurrence of conduct problems in children [1, 6, 49]. However, a notable proportion of fathers (18%) were using only one or none of the effective discipline strategies that were included in the survey. Although the interview did not comprise an exhaustive list of effective discipline strategies (e.g., using a consequence that fits the situation was not included in the survey), it is concerning that a relatively large number of fathers had such a limited repertoire of effective strategies for dealing with misbehavior.

BFIs provide parents with alternatives to coercive discipline strategies because these types of strategies have been found to be associated with the development of conduct problems in children [7, 50]. The present study found that almost half of fathers reported using one or more coercive parenting strategies to deal with their child’s misbehavior. Corporal punishment strategies were notably prevalent. Forty-two percent of fathers reported that they were likely or very likely to give their child a single smack with their hand and 7% of fathers reported that they were likely to smack their child multiple times or with an object.

The current study also aimed to identify those factors that were associated with father reports of child behavior risk, along with those factors related to an increased likelihood of using coercive parenting strategies. Not surprisingly, this study found that child behavior risk and fathers’ use of coercive parenting strategies were significantly associated, which is consistent with past research that has found links between use of corporal punishment by fathers and preschool behavior problems [19]. In addition, fathers’ ratings of the difficulty of their child’s behavior were a unique predictor of smacking once or smacking multiple times or with an object. Fathers who used coercive parenting strategies also tended to view the parenting experience as demanding and stressful. The finding that the degree to which children’s behavior was difficult was linked to a greater likelihood of fathers smacking their children suggests that fathers dealing with severe child misbehavior would benefit from education about the ineffectiveness of this tactic, especially in the face of difficult and disruptive child behavior.

Consistent with previous research [23], father stress was a unique predictor of child behavior difficulty. Because we have reported cross-sectional data, we cannot determine whether fathers’ level of stress is a cause or an effect of the experience of managing the difficult behavior of their child, although it is likely that the association is bi-directional [28]. Nevertheless, father stress is a potentially important target in parenting interventions and highly stressed fathers may constitute a group of high-risk fathers who warrant specific attention. At the very least, the association between father stress and child behavior difficulty suggests that intervening with child behavior problems may have a positive impact on father stress levels.

Socio-demographic factors were important predictors of child behavior problems. Low combined household income was uniquely related to elevated levels of ODD symptoms, while not being in paid employment was independently associated with difficult child behavior. This finding is consistent with past research that has identified socioeconomic disadvantage as being associated with the development of disruptive behavior disorders in children [51] and as a contributing factor in the transition from ODD to conduct disorder [52].

We should be cautious, however, about interpreting this finding to mean that BFIs for disruptive behavior disorders should be targeted only at families of low socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic factors are distal predictors of child behavior difficulty [53], and it would be more informative to classify fathers as ‘high-risk’ on the basis of factors that are more proximally and directly related to child behavior outcomes, such as parental stress and depression and marital conflict. In addition, focusing only on fathers from low socioeconomic backgrounds is likely to have little impact on the problem of inappropriate and coercive parenting practices, given that the present study found that socioeconomic factors were unrelated to fathers’ use of each of the coercive parenting strategies. The finding that these practices occur in all socioeconomic groups provides support for universal programs that make parenting support and intervention accessible and available to all fathers.

The challenge, of course, is engaging fathers in parenting interventions. Consistent with research on father participation in trials of childhood interventions for behavioral and emotional problems [9, 10], few fathers in the current study had sought help from professionals or participated in parenting programs, even when they indicated that their child had experienced behavioral or emotional problems in the past 6 months. Interestingly, higher participation in parenting programs was related to social advantage (i.e., better educated, higher income, being in paid employment), whereas seeing a professional about child behavior problems was associated with social disadvantage (i.e., being single, less likely to be in paid employment, less likely to have completed high school). This finding suggests that when fathers living in lower socioeconomic circumstances seek help for child behavior problems, they do not necessarily seek support for parenting and/or are not being referred by their health practitioner or their child’s teacher to parenting programs. Lower rates of participation in parenting programs among disadvantaged fathers is likely to be linked to a combination of factors, including a lack of awareness of these services and/or their benefits, perceptions that the programs are unsuited to their needs, or incongruence between traditional means of accessing these services and father preferences and life circumstances [54]. This finding highlights the need for continued efforts to engage disadvantaged fathers in parenting services and programs, particularly since evidence from clinical trials indicates that low-income parents can do just as well as other parents in parenting programs if given the opportunity and means to complete them [55]. However, based on the low rates of participation across the entire sample of fathers coping with child behavior or emotional problems, it seems critical for research to be directed at strategies that enhance the engagement of all fathers and that highlight the importance of fathers’ parenting roles.

Since relationship conflict is associated with negative child outcomes for both mothers and fathers [38], it was encouraging that fathers in a relationship rated their partner as being supportive in their parenting role and reported that they and their partner tended to agree about parenting and discipline issues. A partner being supportive was associated with positive perceptions about parenting, positive child behavior outcomes, high parenting confidence, low father stress and depression, and higher participation in parenting programs. Similarly, fathers who agreed with their partner about child discipline had more confidence in their parenting skills, viewed parenting positively, and were less likely to be depressed and to have a child with a behavior or emotional problem. Thus, getting on well with a partner seemed to function as a protective factor for fathers’ own wellbeing and for the functioning of their child, which is consistent with previous research that has highlighted the impact of relationship conflict on parenting quality and child behavior [35–37].

Some limitations suggest caution in interpretation of these results. Firstly, the current study used a DSM symptom count to identify children with problematic levels of oppositional defiant behavior. Use of in-depth, standardized questionnaire and interview measures that collect impairment and developmental-appropriateness information would have allowed these child behavior patterns to be confirmed. The use of the CATI survey method precluded the collection of collateral information from mothers or teachers. Although fathers are obviously in the best position to comment on their own parenting experiences, corresponding information from mothers in particular would have allowed for comparisons to be drawn between mothers’ and fathers’ experiences and corroborating information to be obtained about the presence and severity of child behavior and emotional problems. An additional limitation relates to the lack of data about the number of hours spent working versus the number spent at home, which would provide a proxy measure of the impact of work on the parenting experiences of fathers. Balancing work and family responsibilities is likely to be a central issue for the majority of fathers. Finally, the use of a telephone survey may have resulted in an underrepresentation of indigenous and minority fathers. Despite these cautions, the size of the sample, rigor in data collection and congruence between different measures leads us to believe that these results provide an accurate and comprehensive picture of the experience of fathers.

As a significant minority of fathers experience problems with their children and engage in parenting practices that contribute to the development or maintenance of these problems, there is a need to develop parenting programs that attract and engage fathers. The relative absence of fathers in BFIs is likely to be due to a mix of factors related to present approaches to involving fathers in treatment, the design and delivery method of these interventions, and characteristics of the fathers targeted for treatment [54]. At present it is not clear whether fathers consider existing evidence-based parenting programs unsuited to or irrelevant to their needs or whether existing programs are sufficient and additional strategies are needed to increase awareness, motivation, and commitment. Research that clarifies fathers’ parenting needs and preferences will facilitate the design of more father-friendly programs, which in turn should improve participation rates. The effectiveness of specific strategies to engage fathers in BFIs should also be explored, such as media messages about positive parenting that emphasise the important role of fathers in child development, and targeting contexts relevant to fathers, including the workplace, sports events, and other activities or locations frequented by fathers. This line of research will have implications for the design of community-based prevention programs for emotional and behavioral disorders in children in terms of ensuring that parenting messages and programs are inclusive of the needs and preferences of both mothers and fathers.

Summary

The present study provided a snapshot of the day-to-day parenting experiences of fathers. Results from this study indicated that most fathers find parenting a generally positive experience, do not have any concerns about their child’s behavior, and feel well-supported by their partners in their role as fathers. However, a small but notable proportion of fathers reported potentially clinically significant levels of disruptive behavior in their child and reported engaging in more than one parenting strategy that is coercive and/or involves physical punishment. Despite fathers’ reported difficulties with child behavior and their use of less optimal parenting strategies, fathers reported low rates of participation in parenting programs, with even lower rates among socially disadvantaged fathers. Such findings suggest a need for further research regarding engagement of fathers in evidence-based parenting support, including an examination of practical, individual, and program-related factors that prevent fathers accessing support that is likely to be beneficial.

References

Patterson GR (1982) Coercive family process. Castalia, Eugene

Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR (2008) Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37(1):215–237

Prinz RJ, Dumas JE (2004) Prevention of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder in children and adolescents. In: Barrett P, Ollendick TH (eds) Handbook of interventions that work with children and adolescents: from prevention to treatment. Wiley, Chichester, pp 475–488

Serketich WJ, Dumas JE (1996) The effectiveness of behavioral parent training to modify antisocial behavior in children: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther 27:171–186

Prinz RJ, Jones TL (2003) Family-based interventions. In: Essau CA (ed) Conduct and oppositional defiant disorders: epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, pp 279–298

Sanders MR (2008) The triple P-Positive Parenting Program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting. J Fam Psychol 22(4):506–517

Snyder J, Reid J, Patterson G (2003) A social learning model of child and adolescent antisocial behavior. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A (eds) Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. Guilford Press, New York, pp 27–48

Taylor TK, Biglan A (1998) Behavioral family interventions for improving child-rearing: a review of the literature for clinicians and policy-makers. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 1:41–60

Lundahl BW, Tollefson D, Risser H, Lovejoy MC (2008) A meta-analysis of father involvement in parent training. Res Social Work Pract 18(2):97–106

Phares V, Lopez E, Fields S, Kamboukos D, Duhig AM (2005) Are fathers involved in pediatric psychology research and treatment? J Pediatr Psychol 30(8):631–643

Lamb ME (2004) The role of the father in child development, 4th edn. Wiley, Hoboken

Parke RD (2002) Fathers and families. In: Bornstein MH (ed) Handbook of parenting: vol 3: being and becoming a parent, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 27–73

Phares V (1996) Fathers and developmental psychopathology. Wiley, Oxford

Isley S, O’Neil R, Parke RD (1996) The relation of parental affect and control behaviors to children’s classroom acceptance: a concurrent and predictive analysis. Early Educ Dev 7:7–23

Amato PR, Rivera F (1999) Paternal involvement and children’s behavior problems. J Marriage Fam 61:375–384

NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2004) Fathers’ and mothers’ parenting behavior and beliefs as predictors of children’s social adjustment in the transition to school. J Fam Psychol 18:628–638

Keown LJ (2009) Fathering and mothering of preschool boys with hyperactivity. Manuscript submitted for publication

Baker BL, Heller TL (1996) Preschool children with externalizing behaviors: experience of fathers and mothers. J Abnorm Child Psychol 24:513–532

Burbach AD, Fox RA, Nicholson BC (2004) Challenging behaviors in young children: the father’s role. J Genet Psychol 165:169–183

Stormshak EA, Speltz ML, DeKlyen M, Greenberg MT (1997) Observed family interaction during clinical interviews: a comparison of families containing preschool boys with and without disruptive behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol 25:345–357

DeKlyen M, Biernbaum MA, Speltz ML, Greenberg MT (1998) Fathers and preschool behavior problems. Dev Psychol 34:264–275

Denham SA, Workman E, Cole PM, Weissbrod C, Kendziora KT, Zahn-Waxler C (2000) Prediction of externalizing behavior problems from early to middle childhood: the role of parental socialization and emotion expression. Dev Psychopathol 12:23–45

Calzada EJ, Eyberg SM, Rich B, Querido JG (2004) Parenting disruptive preschoolers: experiences of mothers and fathers. J Abnorm Child Psychol 32(2):203–213

Davé S, Sherr L, Senior R, Nazareth I (2008) Associations between paternal depression and behavior problems in children of 4–6 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17:306–315

Kane P, Garber J (2004) The relations among depression in fathers, children’s psychopathology, and father–child conflict: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 24:339–360

Marchand JF, Hock E (1998) The relation of problem behaviors in preschool children to depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers. J Genet Psychol 159(3):353–366

Ramchandi P, Stein A, Evans J, O’Conner T, The ALSPAC study team (2005) Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: a prospective population study. Lancet 365:2201–2205

Gross HE, Shaw DS, Moilanen KL, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN (2008) Reciprocal models of child behavior and depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers in a sample of children at risk for early conduct problems. J Fam Psychol 22(5):742–751

Cummings EM, Goeke-Morey MC, Papp LM (2001) Couple conflict, children, and families: it’s not just you and me, babe. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Clements M (eds) Couples in conflict. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Manwah

Grych JH, Fincham FD (1990) Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: a cognitive contextual framework. Psychol Bull 108:267–290

Fauber R, Long N (1991) Children in context: the role of the family in child psychopathology. J Consult Clin Psychol 59:813–820

Kerig PK, Cowan PA, Cowan CP (1993) Marital quality and gender differences in parent–child interaction. Dev Psychol 29(6):931–939

Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M (1999) Marital conflict management skills, parenting style, and early-onset conduct problems: processes and pathways. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(6):917–927

Mahoney A, Jouriles EN, Scavone J (1997) Marital adjustment, marital discord over childrearing, and child behavior problems: moderating effects of child age. J Clin Child Psychol 26(4):415–423

Goeke-Morey MC, Cummings EM (2007) Impact of father involvement: a closer look at indirect effects models involving marriage and child adjustment. Appl Dev Sci 11(4):221–225

Lee CM, Beauregard C, Bax KA (2005) Child-related disagreements, verbal aggression, and children’s internalising and externalising behavior problems. J Fam Psychol 19(2):237–245

O’Leary SG, Vidair HB (2005) Marital adjustment, child-rearing disagreements, and overreactive parenting: predicting child behavior problems. J Fam Psychol 19(2):208–216

Coiro MJ, Emery RE (1998) Do marriage problems affect fathering more than mothering? A quantitative and qualitative review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 1(1):23–40

Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Rinaldis M, Firman D, Baig N (2007) Using household survey data to inform policy decisions regarding the delivery of evidence-based parenting interventions. Child Care Health Dev 33:768–783

Zubrick SR, Silburn SR, Garton A, Burton P, Dalby R, Carlton J, Shephard C, Lawrence D (1995) Western Australia child health survey: developing health and well-being in the nineties. Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Institute for Child Health Research, Perth

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC

Bandura A (1977) Social learning theory. Prentice Hall, Oxford

Bandura A (1995) Self efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge University Press, New York

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer, New York

Theodore AD, Chang JJ, Runyan DK, Huner WH, Bangdiwala SI, Agans R (2005) Epidemiologic features of the physical and sexual maltreatment of children in the Carolinas. Pediatrics 115:e331–e337

Jaccard J, Guilamo-Ramos V (2002) Analysis of variance frameworks in clinical child and adolescent psychology: issues and recommendations. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 31(1):130–146

Lavigne JV, LeBailly SA, Hopkins J, Gouze KR, Binns HJ (2009) The prevalence of ADHD, ODD, depression and anxiety in a community sample of 4-year-olds. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 38(3):315–328

Sawyer MG, Arney FM, Baghurst PA, Clark JJ, Graetz BW, Kosky RJ, Nurcombe B, Patton GC, Prior MR, Raphael B, Rey J, Whaites LC, Zubrick SR (2000) The mental health of young people in Australia: child and adolescent component of the national survey of mental health and well-being. Mental Health and Special Programs Branch, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra

Webster-Stratton C (2005) The incredible years: a training series for the prevention and treatment of conduct problems in young children. In: Hibbs ED, Jensen PS (eds) Psychosocial treatment research of child and adolescent disorders. APA, Washington DC, pp 507–555

McKee L, Roland E, Coffelt N, Olson A, Forehand R, Massari C et al (2007) Harsh discipline and child problem behaviors: the roles of positive parenting and gender. J Fam Violence 22:187–196

Sanson A, Smart D, Prior M, Oberklaid F (1993) Precursors of hyperactivity and aggression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32(6):1207–1216

Loeber R, Green SM, Keenan K, Lahey BB (1995) Which boys will fare worse? Early predictors of the onset of conduct disorder in a six-year longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34(4):499–509

Prior M, Sanson A, Carroll R, Oberklaid F (1989) Social class differences in temperament ratings of preschool children. Merrill-Palmer Q 35:239–248

Fabiano G (2007) Father participation in behavioral parent training for ADHD: review and recommendations for increasing inclusion and engagement. J Fam Psychol 21(4):683–693

Zubrick SR, Ward KA, Silburn SR, Lawrence D, Williams AA, Blair E, Robertson D, Sanders M (2005) Prevention of child behavior problems through universal implementation of a group behavioral family intervention. Prev Sci 6(4):287–304

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0503-1.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanders, M.R., Dittman, C.K., Keown, L.J. et al. What are the Parenting Experiences of Fathers? The Use of Household Survey Data to Inform Decisions About the Delivery of Evidence-Based Parenting Interventions to Fathers. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 41, 562–581 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-010-0188-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-010-0188-z