Abstract

Affective and interpersonal instability, both core features of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), have been suggested to underlie non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is the method of choice when investigating dynamic processes. Previously no study addressed affective and interpersonal instability in daily life of adolescents engaging in NSSI. Female adolescents with NSSI (n = 26) and age- and sex-matched healthy controls (n = 20) carried e-diaries on 2 consecutive weekends and were prompted in hourly intervals to rate their momentary affective state and feelings of attachment towards their mother and best friend. The majority of participants in the NSSI group also fulfilled diagnostic criteria for BPD (73%). Squared successive differences were calculated to quantify instability. Adolescents with NSSI reported less positive affect, t (44) = 6.94, p < 0.01, lower levels of attachment to the mother, t (44) = 5.53, p < 0.01, and best friend, t (44) = 4.36, p < 0.01. Both affective, t (44) = −5.55, p < 0.01, and interpersonal instability, mother: t (44) = −4.10, p < 0.01; best friend: t (44) = −4.57, p < 0.01, were significantly greater in adolescents engaging in NSSI. In the NSSI group, the number of BPD criteria met was positively correlated with affective instability, r = 0.40, p < 0.05, and instability of attachment to the best friend, r = 0.42, p < 0.05, but not instability of attachment towards the mother, r = 0.06, p = 0.79. In line with previous work in adults, NSSI is associated with affective and interpersonal instability assessed by EMA in adolescents. Preliminary findings highlight the association of affective and interpersonal instability with diagnostic criteria for BPD. Clinical implications and avenues for further research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Among adolescents, 17.2% report engagement in non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI; i.e., the self-directed act of harming one’s own body tissue by cutting or burning etc. without suicidal intent; Swannell et al. 2014). The World Health Organization has recognized NSSI as one of the top five major health threats to adolescents (World Health Organization 2014). While reasons to engage in NSSI are manifold, functions of NSSI are best described as two-factorial, constituting of two conceptually distinguishable constructs, (1) intrapersonal functions (i.e., affect regulation), and (2) social functions (i.e., interpersonal influence) (Klonsky et al. 2015). This two-factor structure has been found across samples (i.e., adolescents, young adults, adults) and settings (i.e., university, clinical; Klonsky and Glenn 2008; Nock and Prinstein 2004), suggesting that it probably generalizes to diverse populations (Klonsky et al. 2015).

Regarding the intrapersonal functions of self-injury, NSSI is associated with difficulties in emotion regulation (Gratz and Roemer 2008) and youth engaging in NSSI report greater emotion reactivity (Nock et al. 2008). NSSI occurs during states of highest negative mood and is capable to (momentarily) reduce intense emotions (Kamphuis et al. 2007) supporting its overall function to reduce negative affect (Klonsky 2007). Positive affect following acts of NSSI may promote maintenance of NSSI and has been linked to more life-time acts of NSSI (Jenkins and Schmitz 2012).

With respect to the social functions of NSSI, self-injury is closely linked to insecure attachment to the mother (Bureau et al. 2010), the occurrence of interpersonal stressful life events (Burke et al. 2015), and perceived feelings of rejection (Nock et al. 2009). Adolescents engaging in NSSI report to be more interpersonally sensitive (Kim et al. 2015). Adolescents with high genetic susceptibility (related to the coding for the serotonin transporter) and environmental exposure to chronic interpersonal stress are at the greatest risk to report engagement in NSSI (Hankin et al. 2015). In return, the interpersonal model of NSSI proposes that social reinforcement of NSSI (i.e., increases of positive relationship quality or increased support and attention following NSSI) may support maintenance of NSSI in adolescents (Hilt et al. 2008).

Recurrent NSSI is a core feature of borderline personality disorder (BPD) (American Psychiatric Association 2013). BPD is characterized by a pervasive pattern of emotional instability, interpersonal dysfunction, impulsivity, and disturbed self-image (Lieb et al. 2004). The disorder usually emerges during adolescence and continues into adulthood (Kaess et al. 2014). It is regarded as both a dimensional construct and a disorder, and has recently been confirmed as a diagnosis for adolescents in the new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013). BPD is very common among female adolescent inpatients with repetitive NSSI (Nock et al. 2006). A recent study investigating the overlap of NSSI disorder and BPD among clinical adolescents revealed that BPD occurred in 52% of adolescents with NSSI (Glenn and Klonsky 2013). In addition, dimensional BPD pathology seems to underlie repetitive self-harm in a substantial proportion of adolescents (Kaess et al. 2016), and the number of BPD criteria met is predictive of whether or not an adolescent has engaged in NSSI (Jacobson et al. 2008). In turn, adolescent BPD is frequently characterized by an over representation of acute symptoms (Kaess et al. 2014), in particular risk-taking and self-harming behavior, that present important developmental trajectories to BPD (Nakar et al. 2016).

While the majority of adolescents with BPD engage in NSSI, not all adolescents engaging in NSSI fulfill diagnostic criteria for BPD. NSSI and BPD may represent either separate but often comorbid diagnostic entities (Glenn and Klonsky 2013), or different degrees of symptom severity lying on the same dimensional spectrum of pathology (Kaess et al. 2016). We propose that NSSI and BPD should share important underlying characteristics such as emotion dysregulation and interpersonal instability but to a different degree. In line with this view, a recent study in adults revealed that those with a history of NSSI and comorbid BPD report greater emotion dysregulation compared to those without comorbid BPD (Turner et al. 2015). However, differences in emotion dysregulation and even more differences in interpersonal regulation comparing adolescents engaging in NSSI with and without BPD have not been empirically addressed.

To summarize, both NSSI and BPD in adolescence seem associated with affective and interpersonal instability, but previous research has relied on self- or rater-based retrospective reports of perceived instability. However, it is questionable whether humans are capable to adequately report past dynamics. Empirical evidence shows that retrospective measures, such as interviews or questionnaires, are quite limited to reproduce the dynamics of experienced symptomatology (Solhan et al. 2009; Trull and Ebner-Priemer 2013). By enabling repeated assessments of momentary states, ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is well suited to track symptom dynamics and within-person processes over time in everyday life. Accordingly, EMA is suited for examining daily life experiences (Kahneman et al. 2004) and the favored assessment methodology to investigate unstable symptomatology (Ebner-Priemer et al. 2009; Santangelo et al. 2014a; Solhan et al. 2009; Trull and Ebner-Priemer 2013). EMA has been successfully used to examine NSSI in daily live, however almost exclusively in adults. In an adult sample, greater NSSI urges and higher rates of NSSI were reported on days with heightened levels of interpersonal conflict (Turner et al. 2016). Feelings of perceived rejection and isolation (Snir et al. 2015) as well as increased negative emotions (Armey et al. 2011) antecede episodes of NSSI in adults. EMA studies also identified affective instability as a significant predictor of NSSI in adults engaging in NSSI (Anestis et al. 2012; Selby et al. 2013). Only one EMA study examined NSSI in a mixed community based sample of adolescents and young adults who reported thoughts of NSSI (Nock et al. 2009). The study addressed the contexts in which acts of NSSI occurred and did not assess emotional or interpersonal instability underlying NSSI with or without comorbid BPD.

Hypotheses

Here we aimed to address momentary affective and interpersonal instability in the daily life of adolescents engaging in NSSI. Thus, the aim of the present study was to examine affective instability and instability of attachment to significant others in adolescents with NSSI compared to healthy controls. On the basis of clinical theories and diagnostic observations, it was hypothesized that affective and interpersonal instability are greater in adolescents engaging in NSSI compared to controls. Further, given the overlap of NSSI and BPD and the importance of affective instability and unstable interpersonal relationships for both, we aimed to explore the associations in these domains in adolescents with NSSI. It was hypothesized that the number of BPD criteria met is positively correlated to heightened affective and interpersonal instability among adolescents with NSSI.

Methods

General Procedures

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical Faculty, Heidelberg University, Germany (Study: ID S-448/2014) and carried out in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association 2013). Adolescents with DSM-5 (section 3) diagnoses of NSSI were recruited consecutively from the specialized outpatient clinic for risk-taking and self-harm behavior (AtRiSk; Ambulanz für Risikoverhalten & Selbstschädigung) at the Clinic for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Centre of Psychosocial Medicine, University of Heidelberg. Healthy controls matched for age and sex were recruited via public advertisements. Recruitment was restricted to female adolescents, given potential sex differences in the prevalence and underpinnings of NSSI (Brunner et al. 2014; Swannell et al. 2014). All participants and their legal guardians provided written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Sample

The sample comprised 26 adolescents with NSSI, reporting at least five incidents of NSSI during the past 12 months according to DSM-5 section 3 diagnostic criteria (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Patients with a history of psychosis or bipolar disorder were excluded from the study. For the healthy control group, individuals with any current or past self-injury, Axis I or Axis II disorder diagnoses were excluded.

Psychiatric Diagnoses

To assess NSSI, the German version of the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behavior Interview (SITBI-G, Fischer et al. 2014) was used. The respective parts of the German version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II (SCID-II, Fydrich et al. 1997) were used to assess BPD. In the NSSI group, Axis I disorders were assessed using the German version of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID 6.0, Sheehan et al. 2010), whereas in the healthy control group, the German version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Diagnoses/Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP, First et al. 2002) was administered to confirm the absence of any current or past psychiatric disorder. As depicted in Table 1, comorbidities were common in the NSSI group. The vast majority of participants in the NSSI group fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for BPD. Other frequent comorbid diagnoses included mood and anxiety disorders.

E-Diary Procedure

Data on momentary affective and interpersonal instability were collected during participants’ daily lives. After completing the diagnostic assessments, participants received a study smartphone with the movisensXS app (Movisens GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). The app allows the programming of the smartphones to function as an electronic diary. All participants were thoroughly instructed and trained regarding the use of the smartphone. The actual e-diary assessments started the following weekend. Participants carried the e-diary on two consecutive weekends (i.e., on a total of four days). Assessment days were solely on weekends, because participants attended school on weekdays where smartphone use was prohibited. The e-diary emitted a prompting signal according to a random time-sampling schedule on average once per hour (i.e., in 60 min intervals) with a target number of 12 assessments per person per day. The promptings started at 10 am and finished regularly at 10 pm up to 12 am, depending on completed prompts. The procedure was chosen to maximize participants’ compliance and to increase the probability to obtain 12 assessments per participant per day. Each response was automatically time-stamped by the app. Data were assessed, uploaded and stored anonymized, and encrypted on both devices and movisens servers. After completing the assessments on the second weekend, participants returned the smartphones, were debriefed and financially compensated. Participants received 12 Euros for taking part in the diagnostic interview and 1 Euro for every completed entry, given a minimum of 50% completed prompts.

E-Diary Assessments

At each prompt, participants were asked to rate their momentary affect and current attachment to significant others. To assess participants’ current affective states we used an adaption of the Multidimensional Mood Questionnaire designed for the usage in e-diary studies (Wilhelm and Schoebi 2007). Participants responded to the statement “at this moment I feel” by means of four bipolar items (two positively poled items: “unwell–well“,“agitated–calm“; and two negatively poled items: “content–discontent“,“relaxed–tense“). Participants rated each item on a visual analog scale ranging from 0 to 100. This scale has shown both very good psychometric properties and good sensitivity to change (Wilhelm and Schoebi 2007). To assess participants’ current interpersonal states we used four items regarding the momentary attachment to the participant’s mother and four items regarding the momentary attachment to the best friend (named in the first assessment during the introductory session). The wording of the items to assess momentary interpersonal states to the participant’s mother was as follows: (i) “How close do you feel to your mother right now?”; (ii) “How important is your mother to you right now?”; (iii) “What do you think, how close does your mother feel to you right now?”; (iv) “What do you think, how important are you for your mother right now?”. The same items were used to assess momentary attachment to the participant’s best friend whereby “mother” was replaced by “best friend”. Participants rated each item on visual analog scales ranging from 0 to 100.

Data Preprocessing

We created a composite affect score by inverse scoring the two negatively poled items and then calculating the mean value of the four affect items for each administration of the scale. Possible values of the mean scores range from 0 to 100, whereas a higher score corresponds to a positive affective state. Similar, we created the two attachment scores by calculating the mean value of the four attachment items regarding the momentary attachment to the mother and the momentary attachment to the best friend for each administration of the scale. Possible values of these mean scores range from 0 to 100, whereas higher scores correspond to greater levels of momentary attachment. Dynamic processes such as instability or the ebb and flow of symptom severity over time are best quantified using indices that take the temporal dependency of repeated measurements into account (Ebner-Priemer et al. 2009; Jahng et al. 2008; Trull et al. 2015). Calculating squared successive differences (SSDs) has shown adequacy in quantifying instability in various studies (Ebner-Priemer et al. 2007; Köhling et al. 2016; Santangelo et al. 2014b; Trull et al. 2008). In a first step, SSDs were calculated, i.e., differences of consecutive assessments of the momentary affect ratings and the momentary attachment ratings (mother and best friend) were determined and squared for all participants. We calculated SSDs for intervals ≤150 min between assessments. To account for positively skewed distributions of the SSDs we extracted the square root. Finally, the mean square rooted SSD (RMSSD) per person was determined by calculating an average over all SSDs of the respective outcome variable of each participant to quantify instability of affect, attachment to the mother and attachment to the best friend (i.e., the mean value of the square rooted SSDs of the four affect items, the mean value of the square rooted SSDs of the four items regarding the momentary attachment to the mother and the four items on the attachment to the best friend).

Statistical Analysis

Psychometrics of the affect and the two attachment scales were determined by calculating Omega coefficients (ω), i.e., the reliability of within-person changes over time, as proposed in the recent literature (Bolger and Laurenceau 2013). Differences between groups on sociodemographic and diagnostic variables were tested using two-sided independent-samples t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-Square (χ 2) tests for categorical variables. With regard to the e-diary assessments, the number of available responses was used to calculate the mean as analytic weights when testing the hypotheses. We chose this approach to account for missing data common in EMA studies due to the high number of repeated assessments (Fahrenberg et al. 2007). These weighting procedures account for differences of the accuracy of the estimation of the mean and variance due to the dependency on the number of ratings they are based on. Group differences on mean affect and attachment as well as instability (RMSSD) of affect and interpersonal instability were examined using t-tests, whereas each mean (RMSSD, respectively) was weighted by the number of assessments it was based on. Effect sizes for group difference were determined using Cohen’s d. According to Cohen’s conventional criteria a Cohen’s d = 0.80 constitutes a large, a Cohen’s d = 0.50 a medium and a Cohen’s d = 0.20 a small effect (Cohen 1992). To test the associations between affective instability and instability of attachment, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were also used to determine the relationships between instability and BPD symptom severity (i.e., total number of BPD criteria fulfilled). All analyses were performed using Stata/SE (Version 14.0; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, US) with alpha set to 0.05. The only exception was the use of MPlus (Version 7.4; Muthén and Muthén 2015) to calculate the reliability coefficients. Graphs were prepared using GraphPad Prism (version 6.0, GraphPad Software Inc., USA).

Results

A total of 46 female adolescents between 13 and 18 years of age (mean age 15.9 ± 1.25 years) were enrolled in the study. There were no differences regarding mean age, t (44) = −0.19, p = 0.85, and type of school visited, χ 2 (4) = 5.62, p = 0.23, between the two groups (Table 1). Overall compliance with the hourly assessments was good (82% completed prompts). In total, participants provided 1683 reports. Due to technical problems, five participants (NSSI: n = 3, controls: n = 2) were prompted only on one weekend and therefore missed two complete days of assessments. For three participants of the NSSI group, the e-diary assessments were interrupted due to technical problems. Thus, these participants missed one complete assessment day. As illustrated in Table 2, participants in the control group provided significantly more self-reports compared to participants in the NSSI group, t (44) = 2.73, p < 0.01. The reliability analyses revealed high reliability coefficients, ω affect = 0.84, ω attachment mother = 0.76, ω attachment best friend = 0.83, suggesting that the four item measures of affect, attachment to the mother and attachment to the best friend can assess within-person change over time reliably.

The ratings of momentary states of all participants are depicted in Fig. 1. Statistical analyses of the analytic weights confirmed the interpretation of the raw data.Footnote 1 Adolescents engaging in NSSI reported significantly less positive affect, t (44) = 6.94, p < 0.01, d = 1.88, and lower levels of attachment to the mother, t (44) = 5.53, p < 0.01, d = 1.50 as well as to the best friend, t (44) = 4.36, p < 0.01, d = 1.19 (Fig. 2a). Moreover, participants in the NSSI group reported significantly greater affective instability, t (44) = −5.55, p < 0.01, d = −1.60, greater interpersonal instability towards their mother, t (44) = −4.10, p < 0.01, d = −1.20, as well as significantly greater interpersonal instability towards their best friend, t (44) = −4.57, p < 0.01, d = −1.11, compared to healthy controls as illustrated in Fig. 2b.

Heat Map on (A) Affective and Interpersonal Instability ((B) Mother and (C) Best Friend) by Group. Note: color-coded ratings of momentary affect and attachment towards the mother and the best friend in adolescents engaging in NSSI (n = 26) and healthy controls (n = 20) over the four day assessment period. Each row represents a subject (NSSI = rows 1–26, controls = rows 27–46), and each square represents a self-report assessment in one hour intervals. The color of the squares denotes the momentary affective state (intensity of attachment to the mother and best friend, respectively) ranging from shades of red to shades of green. In Fig. 1a red represents negative and green represents positive momentary affect. In Fig. 1b, c red represents low and green high intensities of attachment to the mother and best friend. The lower part of all three figures is dominated by shades of green, which represents the positive affect ratings and ratings of high levels of attachment to mother and best friend in the controls group. In the upper part of the figures, shades of red, orange and yellow dominate, but shades of green are also represented. Thus, the NSSI patients’ ratings varied over the full range of intensities. The higher rate of color changes within lines (i.e., within subjects) indicates more affect changes (Fig. 1a) and more changes in the attachment to the mother and best friend (Fig. 1b, c) over time and thus depicts the heightened instability in the NSSI group. NSSI: non-suicidal self-injury; affect: affective instability; mother: interpersonal instability towards mother; best friend: interpersonal instability towards best friend

Differences on Affective and Interpersonal State and Affective and Interpersonal Instability by Group. Note: means (bars) and standard deviations (whiskers) in adolescents with NSSI (n = 26) and healthy controls (n = 20); NSSI: non-suicidal self-injury; mean: values reflect mean of assessments; RMSSD: root mean squared successive differences across assessments; affect: affective state; mother: interpersonal attachment towards mother; best friend: interpersonal attachment towards best friend; ***: indicates a significant difference p < .001; p-values derived from t-tests on weighted means

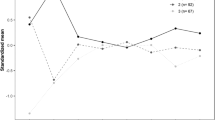

Affective and interpersonal instability were significantly correlated, mother: r = 0.76, p < 0.01; best friend: r = 0.69, p < 0.01, in the entire sample. Similar, interpersonal instability towards mother and towards the best friend were significantly correlated, r = 0.68, p < 0.01. In the NSSI group, the number of BPD criteria met was positively correlated with affective instability, r = 0.40, p < 0.05, and interpersonal instability towards the best friend, r = 0.42, p < 0.05. However, no significant correlation between the number of BPD criteria met and interpersonal instability towards the mother was found, r = 0.06, p = 0.79. Findings on the correlation of affective and interpersonal instability with the number of BPD criteria are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Association of Affective and Interpersonal Instability (Mother and Best Friend) with Criteria for Borderline Personality Disorder in NSSI Group. Note: # BPD criteria: number of BPD criteria fulfilled according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II; data in adolescents engaging in NSSI (n = 26) only; RMSSD: root mean squared successive differences across assessments; affect: affective state; mother: interpersonal attachment towards mother; best friend: interpersonal attachment towards best friend

Discussion

We examined affective and interpersonal instability in adolescents with NSSI and healthy controls by state-of-the-art methodology utilizing e-diaries with high-frequency sampling and a time-sensitive instability index. As hypothesized, adolescents engaging in NSSI reported substantially greater affective and interpersonal instability compared to controls. Findings from subsequent analyses emphasize the importance of comorbid BPD. As hypothesized, BPD symptom severity was positively correlated with affective instability as well as interpersonal instability towards the best friend among adolescents engaging in NSSI. Contrary to our hypotheses, BPD symptom severity was not correlated with interpersonal instability towards the mother.

First, the present results are in favor of current theories on core psychopathology in NSSI and BPD. Affective instability is one of the main characteristics of BPD and therapeutic target of its efficient psychotherapeutic treatment such as dialectic behavioral therapy (DBT; Linehan 1993). Further, it is suggested that core problems of BPD within the interpersonal domain are mediated through limited mentalizing capacity (Bateman and Fonagy 2010) that in turn, from a developmental perspective, is rooted in disorganized attachment (Levy 2005), and can be addressed by mentalization-based treatment (MBT). While theories on the importance of interpersonal instability in BPD are mainly supported by empirical findings in adults, here we provide empirical evidence using innovative methodology, supporting the role of these core pathological traits in adolescents with NSSI and BPD respectively. Second, the present findings illustrate a correlation between BPD symptom severity and greater affective instability and (partially) interpersonal instability among adolescents with NSSI. These results support the idea of a continuum of instability in line with a dimensional approach to personality disorders (American Psychiatric Association 2013). The finding that interpersonal instability to friends but not mothers distinguished between NSSI with and without BPD pathology deserves particular attention. One might speculate that while difficulties in the parent-child relationship are common in the development of NSSI (Bureau et al. 2010; Martin et al. 2011), a more generalized pattern of interpersonal instability, which encroaches on other important relationships, may primarily occur in those who develop BPD. This is in line with current definitions of BPD that require impairments in personality functioning to be consistent across settings and situations (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Indeed, our findings illustrate, that interpersonal instability in those with comorbid BPD extends beyond family functioning (that is affected in NSSI independent of BPD symptoms) to peer relationships (best friend). Studies have shown, that victimization by peers increases the risk of the development of BPD symptoms (Wolke et al. 2012), which may indicate a pattern of ongoing interpersonal difficulties in the development of BPD. Why we can only speculate on the exact reasons and consequences of interpersonal instability towards the best friend in adolescent NSSI, differentiating peer and family relationships in research on the BPD interpersonal style (Gunderson 2007), particular in adolescents, seems a promising avenue for future research.

The study has some limitations that need to be mentioned. We used e-diaries to investigate affective and interpersonal instability in participants’ everyday lives. The downside of this method is that the possibilities to control for potential confounding variables are limited. However, investigating dynamic and state-dependent symptoms in everyday life has the crucial advantage that they are examined in the context where they naturally occur. Thus, experimental symptom induction, a potential threat to validity itself (Fahrenberg et al. 2007; Horemans et al. 2005; Wilhelm and Grossman 2010), is avoided. Furthermore, e-diaries are the method of choice when investigating dynamic processes. By utilizing e-diary methods one can repeatedly assess the variable of interest and therefore actually track the ebb and flow of the dynamic symptom. Choosing the length of time intervals (i.e., the sampling rates) is a particularly important decision, since the sampling rate has to match the temporal dynamics of the underlying target process. Otherwise findings are prone to achieve misleading results (Ebner-Priemer et al. 2009). Notwithstanding its importance, empirically derived recommendations regarding the sampling frequency are rare. However, one study addressed the influence of different time intervals on affective instability (Ebner-Priemer and Sawitzki 2007), and our sampling frequency of once per hour is in line with these recommendations. Even though overall compliance was good, significant group differences with respect to completed prompts emerged. Adolescents engaging in NSSI showed a significantly lower compliance compared to controls. However, controls’ compliance was particularly high (over 90%) and NSSI patients’ compliance was still very good (75%) and above or comparable to the compliance rates in other studies (Höhn et al. 2013; Houben et al. 2016). Here we used analytic weights to account for differences in compliance between NSSI and HC – one of various methods to handle missing data that have been proposed (i.e., multiple imputation, full information maximum likelihood; see Enders 2010 for an overview). In addition, differences between patient group and control group regarding compliance have been reported in EMA studies before (Houben et al. 2016). This study was based on an exclusively female sample, which limits generalization to populations with mixed gender. However, the use of a pure female sample reduced heterogeneity. This may be useful given the literature on sex differences on affect (Fujita et al. 1991) and attachment (Armsden and Greenberg 1987) as well as NSSI prevalence rates (Brunner et al. 2014; Swannell et al. 2014). Our patient sample showed high rates of psychiatric comorbidity. This is in line with reports of high psychiatric comorbidity rates in adolescences engaging in NSSI (e.g., Auerbach et al. 2014) as well as adolescents with BPD (Chanen et al. 2007; Kaess et al. 2013). Thus, our NSSI sample with high rates of BPD and other types of comorbidity seems to be representative. However, we were unable to address the influence of different comorbid diagnosis on affective and interpersonal instability due to our restricted sample size. Studies including clinical controls (e.g., patients with depressive disorders not engaging in NSSI) are clearly needed to assess whether emotional and interpersonal instability are specific to NSSI or associated with underlying psychopathology other than BPD. A further limitation is that participants were prompted only on weekends. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings is constrained since the results may not be valid for weekdays; and replication of the findings is warranted.

The findings have several clinical implications and provide interesting avenues for future research. EMA provides great opportunities for the in-vivo diagnostic assessment of state-dependent symptoms in everyday life, and can help to support clinical diagnoses and decision-making. Further, the assessment of symptom severity – here in the domains of affective and interpersonal instability – on dimensional measures may provide additional information on the severity and time-dependency of symptoms, thus, allowing for a relative evaluation and grading of patients distress. Such approach seems fruitful also for the evaluation of therapeutic interventions such as DBT and MBT targeting these domains of instability. EMA presents a great tool for clinical research, addressing potential changes in affective and interpersonal instability by therapeutic interventions. It also seems promising for the early detection of acute crisis in adolescents with NSSI, BPD and related psychopathology in everyday life and a fruitful avenue for future research.

To summarize, we used e-diaries with high-frequency sampling and a time-sensitive instability index to examine affective and interpersonal instability in adolescents with NSSI and healthy controls. Our results indicate heightened affective instability and greater interpersonal instability in adolescents with NSSI in comparison to controls. Moreover, the results of subsequent analyses highlight the importance of comorbid BPD. The number of BPD criteria met was positively correlated with affective instability as well as instability of attachment to the best friend (but not instability of attachment to the mother). This may indicate a more generalized pattern of interpersonal instability in those with NSSI and BPD pathology. To conclude, using an innovative assessment method our study adds empirical evidence that both affective and interpersonal instability are important factors in adolescent NSSI, particularly in those with comorbid BPD where interpersonal instability seems to be more generalized.

Notes

we double-checked the results using the unweighted raw data, i.e. without weighting each mean (mean rooted squared successive difference, respectively) by the number of assessments it is based on. This procedure led to the same conclusion and results that are available upon request.

References

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Anestis, M. D., Silva, C., Lavender, J. M., Crosby, R. D., Wonderlich, S. A., Engel, S. G., & Joiner, T. E. (2012). Predicting nonsuicidal self-injury episodes over a discrete period of time in a sample of women diagnosed with bulimia nervosa: an analysis of self-reported trait and ecological momentary assessment based affective lability and previous suicide attempts. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45, 808–811. doi:10.1002/eat.20947.

Armey, M. F., Crowther, J. H., & Miller, I. W. (2011). Changes in ecological momentary assessment reported affect associated with episodes of nonsuicidal self-injury. Behavior Therapy, 42, 579–588. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2011.01.002.

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 427–454. doi:10.1007/BF02202939.

Auerbach, R. P., Kim, J. C., Chango, J. M., Spiro, W. J., Cha, C., Gold, J., et al. (2014). Adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: examining the role of child abuse, comorbidity, and disinhibition. Psychiatry Research, 220, 579–584. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.027.

Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2010). Mentalization based treatment for borderline personality disorder. World Psychiatry, 9, 11–15.

Bolger, N., & Laurenceau, J.-P. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: an introduction to diary and experience sampling research. New York: Guilford.

Brunner, R., Kaess, M., Parzer, P., Fischer, G., Carli, V., Hoven, C. W., et al. (2014). Life-time prevalence and psychosocial correlates of adolescent direct self-injurious behavior: a comparative study of findings in 11 European countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 55, 337–348. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12166.

Bureau, J.-F., Martin, J., Freynet, N., Poirier, A. A., Lafontaine, M.-F., & Cloutier, P. (2010). Perceived dimensions of parenting and non-suicidal self-injury in young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 484–494. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9470-4.

Burke, T. A., Hamilton, J. L., Abramson, L. Y., & Alloy, L. B. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury prospectively predicts interpersonal stressful life events and depressive symptoms among adolescent girls. Psychiatry Research, 228, 416–424. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.06.021.

Chanen, A. M., Jovev, M., & Jackson, H. J. (2007). Adaptive functioning and psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 68, 297–306.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

Ebner-Priemer, U. W., & Sawitzki, G. (2007). Ambulatory assessment of affective instability in borderline personality disorder: the effect of the sampling frequency. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 23, 238–247. doi:10.1027/1015-5759.23.4.238.

Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Kuo, J., Kleindienst, N., Welch, S. S., Reisch, T., Reinhard, I., et al. (2007). State affective instability in borderline personality disorder assessed by ambulatory monitoring. Psychological Medicine, 37, 961–970. doi:10.1017/S0033291706009706.

Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Eid, M., Kleindienst, N., Stabenow, S., & Trull, T. J. (2009). Analytic strategies for understanding affective (in)stability and other dynamic processes in psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 195–202. doi:10.1037/a0014868.

Enders, C. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Fahrenberg, J., Myrtek, M., Pawlik, K., & Perrez, M. (2007). Ambulatory assessment--monitoring behavior in daily life settings: a behavioral-scientific challenge for psychology. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 23, 206–213. doi:10.1027/1015-5759.23.4.206.

First, M., Spitzer, R., Gibbon, M., & Williams (2002). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/ NP). New-York: Biometrics Research.

Fischer, G., Ameis, N., Parzer, P., Plener, P. L., Groschwitz, R., Vonderlin, E., et al. (2014). The German version of the self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview (SITBI-G): a tool to assess non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior disorder. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 265. doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0265-0.

Fujita, F., Diener, E., & Sandvik, E. (1991). Gender differences in negative affect and well-being: the case for emotional intensity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 427–434.

Fydrich, T., Renneberg, B., Schmitz, B., & Wittchen, H. (1997). Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV Achse II: Persönlichkeitsstörungen (SKID-II). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Glenn, C. R., & Klonsky, E. D. (2013). Nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: an empirical investigation in adolescent psychiatric patients. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42, 496–507. doi:10.1080/15374416.2013.794699.

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2008). The relationship between emotion dysregulation and deliberate self-harm among female undergraduate students at an urban commuter university. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 37, 14–25. doi:10.1080/16506070701819524.

Gunderson, J. G. (2007). Disturbed relationships as a phenotype for borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(11), 1637–1640. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071125.

Hankin, B. L., Barrocas, A. L., Young, J. F., Haberstick, B., & Smolen, A. (2015). 5-HTTLPR × interpersonal stress interaction and nonsuicidal self-injury in general community sample of youth. Psychiatry Research, 225, 609–612. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.037.

Hilt, L. M., Nock, M. K., Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., & Prinstein, M. J. (2008). Longitudinal study of nonsuicidal self-injury among young adolescents: rates, correlates, and preliminary test of an interpersonal model. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 28, 455–469. doi:10.1177/0272431608316604.

Höhn, P., Menne-Lothmann, C., Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., Jacobs, N., Derom, C., et al. (2013). Moment-to-moment transfer of positive emotions in daily life predicts future course of depression in both general population and patient samples. PloS One, 8, e75655. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075655.

Horemans, H. L. D., Bussmann, J. B. J., Beelen, A., Stam, H. J., & Nollet, F. (2005). Walking in postpoliomyelitis syndrome: the relationships between time-scored tests, walking in daily life and perceived mobility problems. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 37, 142–146. doi:10.1080/16501970410021526.

Houben, M., Vansteelandt, K., Claes, L., Sienaert, P., Berens, A., Sleuwaegen, E., & Kuppens, P. (2016). Emotional switching in borderline personality disorder: a daily life study. Personality Disorders, 7, 50–60. doi:10.1037/per0000126.

Jacobson, C. M., Muehlenkamp, J. J., Miller, A. L., & Turner, J. B. (2008). Psychiatric impairment among adolescents engaging in different types of deliberate self-harm. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 363–375. doi:10.1080/15374410801955771.

Jahng, S., Wood, P. K., & Trull, T. J. (2008). Analysis of affective instability in ecological momentary assessment: indices using successive difference and group comparison via multilevel modeling. Psychological Methods, 13, 354–375. doi:10.1037/a0014173.

Jenkins, A. L., & Schmitz, M. F. (2012). The roles of affect dysregulation and positive affect in non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research, 16, 212–225. doi:10.1080/13811118.2012.695270.

Kaess, M., von Ceumern-Lindenstjerna, I.-A., Parzer, P., Chanen, A., Mundt, C., Resch, F., & Brunner, R. (2013). Axis I and II comorbidity and psychosocial functioning in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology, 46, 55–62. doi:10.1159/000338715.

Kaess, M., Brunner, R., & Chanen, A. (2014). Borderline personality disorder in adolescence. Pediatrics, 134, 782–793. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3677.

Kaess, M., Brunner, R., Parzer, P., Edanackaparampil, M., Schmidt, J., Kirisgil, M., et al. (2016). Association of adolescent dimensional borderline personality pathology with past and current nonsuicidal self-injury and lifetime suicidal behavior: a clinical multicenter study. Psychopathology. doi:10.1159/000448481.

Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D. A., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2004). A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: the day reconstruction method. Science, 306, 1776–1780. doi:10.1126/science.1103572.

Kamphuis, J. H., Ruyling, S. B. M., & Reijntjes, A. H. (2007). Testing the emotion regulation hypothesis among self-injuring females: evidence for differences across mood states. Journal of Nervous, 195, 912–918. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181593d89.

Kim, K. L., Cushman, G. K., Weissman, A. B., Puzia, M. E., Wegbreit, E., Tone, E. B., et al. (2015). Behavioral and emotional responses to interpersonal stress: a comparison of adolescents engaged in non-suicidal self-injury to adolescent suicide attempters. Psychiatry Research, 228, 899–906. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.001.

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 226–239. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002.

Klonsky, E. D., & Glenn, C. R. (2008). Assessing the functions of non-suicidal self-injury: psychometric properties of the inventory of statements about self-injury (ISAS). Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31, 215–219. doi:10.1007/s10862-008-9107-z.

Klonsky, E. D., Glenn, C. R., Styer, D. M., Olino, T. M., & Washburn, J. J. (2015). The functions of nonsuicidal self-injury: converging evidence for a two-factor structure. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9, 44. doi:10.1186/s13034-015-0073-4.

Köhling, J., Moessner, M., Ehrenthal, J. C., Bauer, S., Cierpka, M., Kämmerer, A., et al. (2016). Affective instability and reactivity in depressed patients with and without borderline pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 30, 776–795. doi:10.1521/pedi_2015_29_230.

Levy, K. N. (2005). The implications of attachment theory and research for understanding borderline personality disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 17, 959–986.

Lieb, K., Zanarini, M. C., Schmahl, C., Linehan, M. M., & Bohus, M. (2004). Borderline personality disorder. Lancet, 364, 453–461. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6.

Linehan, M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford.

Martin, J., Bureau, J.-F., Cloutier, P., & Lafontaine, M.-F. (2011). A comparison of invalidating family environment characteristics between university students engaging in self-injurious thoughts & actions and non-self-injuring university students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1477–1488. doi:10.1007/s10964-011-9643-9.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2015). Mplus User’s Guide (Seventh ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén and Muthén.

Nakar, O., Brunner, R., Schilling, O., Chanen, A., Fischer, G., Parzer, P., et al. (2016). Developmental trajectories of self-injurious behavior, suicidal behavior and substance misuse and their association with adolescent borderline personality pathology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 197, 231–238. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.029.

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 885–890. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885.

Nock, M. K., Joiner, T. E., Gordon, K. H., Lloyd-Richardson, E., & Prinstein, M. J. (2006). Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research, 144, 65–72. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010.

Nock, M. K., Wedig, M. M., Holmberg, E. B., & Hooley, J. M. (2008). The emotion reactivity scale: development, evaluation, and relation to self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Behavior Therapy, 39, 107–116. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2007.05.005.

Nock, M. K., Prinstein, M. J., & Sterba, S. K. (2009). Revealing the form and function of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors: a real-time ecological assessment study among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118, 816–827. doi:10.1037/a0016948.

Santangelo, P., Bohus, M., & Ebner-Priemer, U. W. (2014a). Ecological momentary assessment in borderline personality disorder: a review of recent findings and methodological challenges. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28, 555–576. doi:10.1521/pedi_2012_26_067.

Santangelo, P., Reinhard, I., Mussgay, L., Steil, R., Sawitzki, G., Klein, C., et al. (2014b). Specificity of affective instability in patients with borderline personality disorder compared to posttraumatic stress disorder, bulimia nervosa, and healthy controls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 258–272. doi:10.1037/a0035619.

Selby, E. A., Franklin, J., Carson-Wong, A., & Rizvi, S. L. (2013). Emotional cascades and self-injury: investigating instability of rumination and negative emotion. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 1213–1227. doi:10.1002/jclp.21966.

Sheehan, D. V., Sheehan, K. H., Shytle, R. D., Janavs, J., Bannon, Y., Rogers, J. E., et al. (2010). Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71, 313–326. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi.

Snir, A., Rafaeli, E., Gadassi, R., Berenson, K., & Downey, G. (2015). Explicit and inferred motives for nonsuicidal self-injurious acts and urges in borderline and avoidant personality disorders. Personality Disorders, 6, 267–277. doi:10.1037/per0000104.

Solhan, M. B., Trull, T. J., Jahng, S., & Wood, P. K. (2009). Clinical assessment of affective instability: comparing EMA indices, questionnaire reports, and retrospective recall. Psychological Assessment, 21, 425–436. doi:10.1037/a0016869.

Swannell, S. V., Martin, G. E., Page, A., Hasking, P., & St John, N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 44, 273–303. doi:10.1111/sltb.12070.

Trull, T. J., & Ebner-Priemer, U. (2013). Ambulatory assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 151–176. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185510.

Trull, T. J., Solhan, M. B., Tragesser, S. L., Jahng, S., Wood, P. K., Piasecki, T. M., & Watson, D. (2008). Affective instability: measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 647–661. doi:10.1037/a0012532.

Trull, T. J., Lane, S. P., Koval, P., & Ebner-Priemer, U. W. (2015). Affective dynamics in psychopathology. Emotion Review, 7, 355–361. doi:10.1177/1754073915590617.

Turner, B. J., Dixon-Gordon, K. L., Austin, S. B., Rodriguez, M. A., Zachary Rosenthal, M., & Chapman, A. L. (2015). Non-suicidal self-injury with and without borderline personality disorder: differences in self-injury and diagnostic comorbidity. Psychiatry Research, 230, 28–35. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.058.

Turner, B. J., Cobb, R. J., Gratz, K. L., & Chapman, A. L. (2016). The role of interpersonal conflict and perceived social support in nonsuicidal self-injury in daily life. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi:10.1037/abn0000141.

Wilhelm, F. H., & Grossman, P. (2010). Emotions beyond the laboratory: theoretical fundaments, study design, and analytic strategies for advanced ambulatory assessment. Biological Psychology, 84, 552–569. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.01.017.

Wilhelm, P., & Schoebi, D. (2007). Assessing mood in daily life: structural validity, sensitivity to change, and reliability of a short-scale to measure three basic dimensions of mood. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 23, 258–267. doi:10.1027/1015-5759.23.4.258.

Wolke, D., Schreier, A., Zanarini, M. C., & Winsper, C. (2012). Bullied by peers in childhood and borderline personality symptoms at 11 years of age: a prospective study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(8), 846–855. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02542.x.

World Health Organization. (2014). Health for the world’s adolescents: A second chance in the second decade, Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/files/1612_MNCAH_HWA_Executive_Summary.pdf.

World Medical Association (2013). World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310, 2191–2194. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281053.

Acknowledgements

Julian Koenig is supported by a Physician-Scientist Scholarship provided by the Medical Faculty, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Philip S. Santangelo and Julian Koenig equally contributed to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Santangelo, P.S., Koenig, J., Funke, V. et al. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Affective and Interpersonal Instability in Adolescent Non-Suicidal Self-Injury. J Abnorm Child Psychol 45, 1429–1438 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0249-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0249-2