Abstract

Psychotic experiences (PEs) are robustly associated with subsequent non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicide attempts, but questions remain as to the temporal relation and underlying cause of this association. Most investigations have incorporated only two waves of data, and no study has comprehensively investigated mediating pathways. This study aimed to investigate both the PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt association, and their relevant mediators, across three waves of prospective data. Participants were from an Australian prospective longitudinal cohort of 1100 adolescents (12–17 years); data were collected at three time points over 2 years. NSSI and suicide attempts were measured using the Self-Harm Behaviour Questionnaire. Items from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children were used to assess four PE subtypes (auditory hallucinatory experiences [HEs] and three delusional experiences). Potential mediators of interest included: psychological distress, self-reported mental disorders, self-esteem, recent traumatic life events (e.g. bullying, sexual assault), emotion regulation, and impulsivity/other personality traits. Analyses were adjusted for sociodemographics and substance use. Auditory HEs were indirectly associated with future NSSI and suicide attempts via recent traumatic life events, high psychological distress, and low self-esteem, across three waves of data. Other PE subtypes were generally not associated with incident NSSI/suicide attempts at 1- and 2-year follow-up, either directly or indirectly. These findings highlight the importance of screening for auditory HEs when assessing a young person’s self-harm/suicide risk. Clinical assessment would be further enhanced by a comprehensive review of recent interpersonal traumatic events, as well as levels of self-esteem and distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psychotic experiences (PEs), including hallucinatory and delusional experiences, are common among adolescents [1, 2] and are associated with a broad range of adverse health and social outcomes including non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI; self-harm without suicidal intent) and suicidal thoughts and behaviours [3,4,5]. PEs prospectively predict NSSI [6, 7] and suicide attempts [8,9,10] among adolescents, with large effect sizes, and studies have reported dose–response relationships with regard to both number of PEs [11, 12] and lethality of suicidal behaviour [8, 13, 14]. Whilst the association between PEs and self-injurious behaviours (i.e. NSSI and suicide attempts) has been well-replicated, questions remain as to the temporal relation and underlying cause of these associations.

Most studies have restricted their examination of the PE-self injurious behaviour association to auditory hallucinations [8, 13] or collapsed all types of PEs into one variable [6, 15]. The few studies of adolescents that have investigated different types of PEs (e.g., hallucinatory, persecutory ideation, and bizarre experiences) have found differential strengths in the associations [12, 16], suggesting that some PEs are more likely to be associated with self-injurious outcomes than others. Hielscher et al. [4] investigated five different PE subtypes (auditory and visual hallucinatory experiences, and three delusional experiences) using a cross-sectional nationally representative sample of Australian adolescents. After comprehensive adjustment and consideration for relevant confounders and mediators, only auditory hallucinatory experiences were independently associated with NSSI and suicide attempts [4]. Longitudinal data are required to inform the temporal nature of these associations. To our knowledge, nearly all longitudinal studies to date investigating PE-NSSI or PE-suicide attempt associations have used two waves of data collection, which can be an unreliable source for understanding how two variables affect each other over time. Observing an event at “Time 1” and seeing its impact at “Time 2” offers more insight than a cross-sectional study, however, if one accepts the premise that a longitudinal design should enhance our understanding of relationships and how they change over time, longitudinal designs should ideally contain a minimum of three waves, to allow for more reliable observation of a relationship over time [17]. The first aim of this study was to investigate the association between different PE subtypes and future NSSI and suicide attempts among adolescents using a three-wave prospective cohort study.

Previous investigations of the PE-self injurious behaviour association have inconsistently adjusted for, or considered third variables (i.e. confounders, mediators, moderators). Hielscher et al. [18] reported that 30% of existing studies did not control or account for any third variables of interest. Honings et al.’s [19] meta-analysis found that adjusting for depression resulted in attenuation of the PE-self injurious behaviour association (including NSSI, deliberate self-harm, suicide attempts), which remained significant for all outcomes except deliberate self-harm. It is possible that the PE-self injurious behaviour association is explained entirely by mediators, but studies using structural equation modelling, and using three waves of longitudinal data [20] are needed to explore this possibility, allowing for distinction and quantification of the role of mediators versus confounders (and other third variables). Therefore, the second aim of this study was to investigate several potential mediators of the PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt association using this methodology.

Identifying and assessing the influence of mediators is important in understanding the mechanisms involved in the PE-self injurious behaviour association, which may in turn inform interventions to prevent self-injurious behaviour and suicide [8, 13]. Mediators help explain why the relationship between two variables exists (whereas moderators, for example, explain the strength of a relationship [21, 22]). In terms of key mediating variables of interest, a systematic review of the PE-self-injurious behaviour association [18] identified several clinical and psychosocial variables (e.g. common mental disorders, psychological distress) as potentially important explanatory variables, and Hielscher et al.’s [4] cross-sectional study of adolescents found major depressive disorder had the greatest explanatory power in all PE-NSSI/suicide attempt associations, followed by psychological distress and bullying. Low self-esteem was also a key explanatory variable in the delusional experience-self injurious behaviour association [4]. All these variables should be considered candidates for further examination as mediators of the association.

In addition to these key variables, broader negative and traumatic life events need to be considered in the PE-self-injurious behaviour association [8, 23], but to date have not been extensively investigated [18]. In DeVylder et al.’s [24, 25] fully adjusted models, bullying and childhood physical/sexual trauma attenuated the association with nearly all suicidal outcomes, and Gaweda et al.’s [26] cross-sectional study found PEs and depression mediated the childhood trauma-suicidal behaviour relationship. The roles of historical (childhood trauma) as well as more recent traumatic events (e.g. sexual assault, bullying) during adolescence need to be considered in the PE-self injurious behaviour association. Although emotion dysregulation is theorised to play a key role in the development of self-injury [27, 28], only two studies to date have adjusted for this in the PE-self injurious behaviour association [24, 29]. Finally, personality traits such as impulsivity and reward sensitivity have associations with NSSI and suicide attempts [30, 31], and have been identified as key third variables in the PE–NSSI [32] but not the PE-suicide attempt relationship [33].

We had the opportunity to address our study aims using a prospective longitudinal study of Australian adolescents from whom data were collected at three time points over 2 years. Specifically, we aimed to examine: (1) are baseline PE subtypes associated with future NSSI and suicide attempts over 24 months, and (2) what are the mediators of the association between PEs and NSSI/suicide attempts? Based on previous studies, it is hypothesised that mental health problems (psychological distress, mental disorders and low self-esteem) and exposure to traumatic events such as bullying will be key mediating factors of the PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt association.

Methods

Sample, attrition, and missing data

Participants were drawn from the HEALing Project (Helping to Enhance Adolescent Living), a longitudinal cohort study (three time points, 12 months apart) of Australian adolescents aged 12–17 years, previously described in detail elsewhere [6, 34]. The study was approved by Monash University and The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committees, with approval also obtained from relevant Catholic Education Archdioceses. Consent was provided by school principals, parents, and students. An information sheet and consent form were sent home to parents of 14,841 students from 41 secondary schools (23 Catholic, 18 independent), of which 3119 (21.0%) were returned, a participation rate consistent with previous Australian school-based studies of adolescents [35,36,37]. Of those with parental consent, 2640 (84.6%) students completed the survey at baseline (T0). Of these, 1975 (74.8%) completed the survey at 1-year follow-up (T1), and 1263 (47.8%) completed data at all three waves (T0–T2). Twenty-four participants were excluded because they were older than 17 years at one data collection point (T0 and/or T1 and/or T2), leaving a sample of 1239. See Fig. 1 for study flow chart.

Adolescents lost to follow-up (LTF; n = 1377, either at T1 [n = 665] or T2 [n = 712]; 52.2% of total sample) were older, more likely to be male, report PEs at baseline, and report having engaged in NSSI or suicide attempts at baseline. They were also more likely to report psychological distress, as well as score lower on the Emotion Regulation Questionniare (ERQ) Cognitive Reappraisal subscale and Behavioural Inhibition System (BIS) subscale, and score higher on Behavioural Activation System (BAS) Drive and Fun Seeking subscales (study variables described in detail below). All other variables were not associated with LTF (see Online Resource 1).

In terms of missing data (360 of 1239 participants), 139 participants did not respond to all key items (i.e. PEs, NSSI, suicide attempts) at baseline, T1 and T2, and another 221 did not respond to all mediating variable items. For all analyses, a final sample of n = 1100 was used, where participants had responded to all PE, NSSI, and suicide attempt items at all three time points (T0–T2)Footnote 1 (see Fig. 1; study flow chart). The exception was the mediation analyses (i.e. Aim 2 analyses), where we instead took the approach of pairwise deletion to handle missing data (sample size range = 1051–1211). The ten mediating variables of interest (see variables below) were incorporated for only one of the study’s aims, and too many cases would have been lost if listwise deletion (or complete case analysis) was used.

Key variables

Psychotic experiences PEs were captured using the revised version of The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-R [38]) Schizophrenia Section, including: lifetime auditory hallucinatory experiences (HEs) (‘Have you ever heard voices other people cannot hear?’), and three delusional experiences (DEs) of thoughts being read (‘Have other people ever read your thoughts?’), receiving special messages (‘Have you ever had messages sent just to you through the television or radio?’), and feeling spied upon (‘Have you ever thought that people are following you or spying on you?’). Participants responded to each item as either ‘no’, ‘yes, likely’ or ‘yes, definitely’. These four items have been used to screen for PEs in adolescents [14, 39] and have previously shown high concurrent validity with clinician-rated psychotic symptoms among adolescents, particularly hallucinatory DISC items [40]. Participants in the HEALing study were classified as endorsing PEs at baseline (T0) if they responded ‘yes, definitely’ to relevant DISC-R items. A ‘no’ response was classified if participants responded either ‘no’ or ‘yes, likely’, as consistent with previous studies [34]. Incident PEs at 1- (or 2-year) follow-up were coded if participants responded ‘no’ at T0, but ‘yes, definitely’ at T1 (or T2).

NSSI and suicide attempts NSSI and suicide attempts were assessed using the Self-Harm Behaviour Questionnaire [41]. NSSI was assessed using the item ‘Have you ever hurt yourself on purpose?’ (yes or no); which was preceded by the definition of ‘hurting yourself on purpose without trying to die’.Footnote 2 Incident NSSI 1 year later was coded if participants responded ‘no’ at T0 but ‘yes’ at T1, and incident NSSI 2 years later if participants responded ‘no’ at T0 and T1, but ‘yes’ at T2. Suicide attempts were assessed using the item ‘Did you ever try to end your life?’ (yes or no). Incident attempted suicide at 1- and 2-year follow-up were coded the same way as NSSI variables.

Potential mediators of interest

The choice of potentially mediating variables was guided by the wider literature, a systematic review of confounding and mediating factors of the PE-self injurious behaviour association [18], as well as by a previous cross-sectional study with adolescents [4] which examined the individual contribution of several different clinical and psychosocial variables to the PE-NSSI/suicide attempt relationship. This comprehensive analysis found depression, psychological distress, bullying and self-esteem were key third variables in PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt associations. Variables such as parental mental illness, disordered eating behaviour, and social isolation had negligible effects in nearly all PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt models [4] and therefore, their role was not considered in the current study.

Psychological distress Psychological distress was categorised using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) clinical cut-off. The GHQ-12 is a self-report screening measure extensively used to assess psychological distress over the past few weeks [42]. Although originally developed for adult populations, the GHQ-12 has subsequently been validated among adolescents [43]. Participants were classified according to sex-stratified clinical cut-offs previously reported in an Australian adolescent sample [44]. Males were classified as experiencing psychological distress if they scored ≥ 13, and females were classified if they scored ≥ 18.

Self-reported diagnosis of mental disorders Self-reported mental disorder diagnosis was based on responses to the item ‘Has a doctor ever told you that you have an emotional or behavioural problem?’ (yes or no). To better establish temporal relationships, incident mental disorders at T1 were coded if participants responded ‘no’ at baseline but ‘yes’ at 1-year follow-up (T1) (see ‘Statistical analysis’ section for more details) . Of those participants who reported onset of a mental disorder at T1 (6.7%, 95% CI 5.2–8.1), the most commonly reported diagnoses were depression (n = 29, 39.7%) and anxiety (n = 36, 49.3%; these were not mutually exclusive). No participant at T1 (or any other study time point) reported being diagnosed with schizophrenia or psychosis.

Self-esteem The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [45] is a widely used self-report instrument for measuring trait self-esteem. It is a 10-item Likert scale measuring both positive and negative feelings about the self. The scale has shown acceptable psychometric properties in adolescent samples [46], with satisfactory Cronbach’s alphas (0.89) in the current sample [47].

Traumatic life events in the past 12 months Several longitudinal studies have shown evidence of a bidirectional relationship where PEs predict subsequent traumatic events involving interpersonal harm (e.g. bullying, physical/sexual victimisation) and vice versa, even after adjustment for confounders [23, 48, 49]. Considering this, variables such as bullying and sexual assault should be treated as potentially mediating variables of the PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt associations. In the current study, a recent traumatic life event was coded if participants responded ‘yes within the past 12 months’ at T1 on the Adolescent Life Events Scale (ALES [50]; see Online Resource 2) to any of the following: been bullied at school, seriously physically abused, or forced to engage in sexual activities. In addition to these traumatic events with intent to harm, two additional ALES items with special consideration were included which pertain to recent (past 12 month) exposure to friend/family self-harm or suicide, considering the known phenomenon of social/familial transmission of self-harm and suicide in young people [51]. Supplementary analyses were conducted with and without self-harm/suicide exposure included in the traumatic life event variable. See Online Resource 2 for more details on the ALES measure and traumatic events of interest for this study.

Emotion regulation The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ [52]) is a 10-item, 7-point Likert scale used to assess individual differences in the habitual use of two emotion regulation strategies: Cognitive ReappraisalFootnote 3 (6 items) and Expressive Suppression (4 items). Both subscales have shown acceptable psychometric properties in adolescent samples [52, 54].

Behavioural Inhibition and Activation (BIS/BAS) Scales Gray [55] proposed that personality traits are influenced by two fundamental motivational systems: the Behavioural Inhibition System (BIS) and Behavioural Activation System (BAS). Both systems have been implicated in NSSI and suicide attempts [56, 57]. The BIS/BAS scale [58] is a 24-item Likert scale assessing dispositional behavioural inhibition and behavioural activation, including a global BIS score (7 items) and three separate BAS scores: Drive (4 items), Fun Seeking (4 items), and Reward Responsiveness (5 items). The BIS subscale correlates with measures of susceptibility to punishment and harm avoidance, while the BAS subscales correlate with measures of reward seeking and impulsivity [56]. All BIS/BAS subscales have shown sound psychometric properties in this sample (Cronbach’s alphas ≥ 0.64 [59]).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata/IC 14.

Preparatory analyses Associations between third variables of interest were explored (age, gender, substance use, psychological distress, mental disorders, self-esteem, traumatic life events, emotion regulation scales, behavioural inhibition/activation scales), where no correlation coefficient was above 0.5, indicating these were relatively distinct constructs. There was no multicollinearity as indicated by a variance inflation factor (VIF) of < 3.0 for all variables [60]. NSSI and suicide attempts were modelled separately in this study.

Regression modelling To address Aim 1, logistic regressions were used to examine the total effect of baseline PEs on incident NSSI and incident suicide attempts at T1 and T2; as well as to examine the total effect of T1 PEs on incident NSSI/suicide attempts at T2.

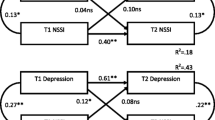

To address Aim 2 of the study (i.e. explanatory role of third variables), the direct and indirect effects of baseline PEs on incident NSSI/suicide attempts at T2 were explored using the Generalised Structural Equation Modelling (GSEM) function. Potential mediators of interest included: psychological distress; self-reported diagnosis of mental disorders; self-esteem; emotion regulation (ERQ Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression subscales); recent traumatic life events; and BIS/BAS subscales. For all these mediating variables, information collected at 1-year follow-up (T1) was used, to better establish temporal relationships between: PEs (captured at T0/baseline) → mediating variable/s (captured at T1/1-year follow-up) → incident self-injurious outcomes (captured at T2/2-year follow-up). Example PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt mediation pathways are outlined in Fig. 2, with psychological distress as the example mediating variable. These same pathways were investigated for all other potentially mediating variables (individually, as well as in a combined, parallel mediation model), for each PE subtype. For direct and indirect effects, we drew 1000 bootstrap samples to generate 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals [61, 62]. If the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval (BC 95% CI) of the indirect effect did not include zero, it was considered statistically significant mediation at the 5% level.

It is optimal to use a three-wave design to test for mediation [63]. However, considering the large amount of attrition across our three waves (52.2% of total sample), supplementary mediation models were conducted using only the first 2 waves of data; where only 25.2% of the sample was LTF. To achieve this, mediation models followed the two-wave approach of MacKinnon and colleagues [61, 64] which takes advantage of the temporal lag and longitudinal regression for both links in the proposed causal chain. See Online Resource 3 for further details.

Confounders Age (in years) and sex of participants were incorporated as confounders in all analyses. In addition, lifetime substance use (cannabis and other illicit substances) was also included as a confounder considering we were not able to separate out PEs occurring under the influence of alcohol or drugs [18]. Drug-related PEs can be differentiated from non-drug-related PEs in terms of a person’s level of functioning and were found to not be related to suicidal behaviour [65].

Results

Demographic characteristics, PEs and NSSI/suicide attempts

There were 1100 participants with complete data collected for all PE, NSSI, and suicide attempt items at baseline (T0), 1-year (T1), and 2-year follow-up (T2). At baseline, their mean age was 13.8 (SE = 0.03), and 75.9% were female. Table 1 shows endorsement of PEs, with 19.9% (95% CI 17.4–22.3) of the sample endorsing any PE at T0, 7.2% reporting incident PEs at T1, and 4.8% reporting incident PEs at T2.

Of the total sample, 93 (8.5%; 95% CI 6.8–10.1) reported NSSI at baseline, and 12 (1.1%; 95% CI 0.5–1.7) reported attempting suicide prior to baseline assessment. In terms of incident NSSI/suicide attempts between baseline and T1, 61 (5.5%, 95% CI 4.2–7.0) participants reported engaging in NSSI, and 9 (0.8%, 95% CI 0.3–1.4) reported incident suicide attempts. In terms of incident NSSI/suicide attempts between T1 and T2, 66 (6.0%, 95% CI 4.6–7.3) participants reported engaging in NSSI, and 19 (1.7%, 95% CI 1.0–2.6) attempted suicide for the first time.

Aim 1: associations between baseline PEs and incident NSSI/suicide attempts

As seen in Table 2, any PE at baseline was associated with NSSI (OR range = 1.78–2.24) and suicide attempts (OR = 2.19) in the following 1–2 years. However, when broken down by subtype, auditory HEs were the only subtype associated with both incident NSSI and suicide attempts, across both time points (except for T1 NSSI). There were wide confidence intervals, however, around estimates of the other PE subtypes (see Table 2).

Aim 2: mediators of the PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt associations

Considering the above, mediation analyses focused on baseline auditory HEs as the independent variable of interest (mediators of the other PE subtypes were also explored in supplementary analyses, see pg. 12).

Mediators of the PE-NSSI association In terms of NSSI, the direct effect of auditory HEs was significant (p < 0.05) in mental disorder, ERQ expressive suppression, and BAS subscale models; auditory HEs’ direct effect was non-significant in all other NSSI models. We found the auditory HE-NSSI association was significantly mediated by psychological distress (b = 0.60, SE = 0.33, BC 95% CI 0.08–1.39), low self-esteem (b = 0.29, SE = 0.11, BC 95% CI 0.12–0.54), recent traumatic life events (b = 1.03, SE = 0.42, BC 95% CI 0.34–1.98), and high BIS scores (b = 0.12, SE = 0.06, BC 95% CI 0.02–0.28) (see Online Resource 4).

Mediators of the PE-suicide attempt association The direct effect of auditory HEs was not significant in any of the suicide attempt models. We found the auditory HE-suicide attempt association was significantly mediated by distress (b = 1.01, SE = 0.56, BC 95% CI 0.16–2.52), low self-esteem (b = 0.49, SE = 0.20, BC 95% CI 0.18–0.97), recent traumatic life events (b = 1.09, SE = 0.66, BC 95% CI 0.20–2.84), and low ERQ cognitive reappraisal (b = 0.18, SE = 0.14, BC 95% CI 0.001–0.62). Mental disorders, ERQ expressive suppression, and most BIS/BAS scales were not significant mediators of the hallucinatory-NSSI nor -suicide attempt relationship; nor did these variables have significant direct effects, except for mental disorders and BAS(reward subscale) in relation to incident suicide attempts (see Online Resource 4).

Parallel mediation models When all key mediating variables (i.e. significant, single mediators) were included simultaneously in the same model (see Fig. 3 for parallel mediation models), traumatic life events in the past 12 months (as reported at T1) was the remaining significant mediator of the hallucinatory-NSSI (b = 0.83, SE = 0.37, BC 95% CI 0.17–1.72; Pathway a: OR = 2.08, 95% CI 1.22–3.55, Pathway b: OR = 3.10, 95% CI 1.78–5.40) and hallucinatory-suicide attempt relationship (b = 0.62, SE = 0.46, 95% CI 0.28–1.53); although the latter was no longer significant when confounders and bias-corrected bootstrapping were applied (b = 0.59, SE = 0.57, BC 95% CI − 0.12 to 2.12; Pathway a: OR = 2.21, 95% CI 1.30–3.74, Pathway b: OR = 2.13, 95% CI 0.76–5.92). In supplementary analyses (data not shown) where the two self-harm/suicide exposure variables were removed, NSSI findings remained consistent. Recent traumatic life events remained a significant mediator in both single and parallel HE-NSSI mediation models when only bullying, sexual assault, and physical abuse were included. This was not the case for suicide attempts, where recent traumatic events became a non-significant mediator (in both single and parallel mediation models) when self-harm/suicide exposure variables were removed. Of note, no single traumatic life event was a significant mediator of any of the associations.

a Parallel mediation model of key mediating variables in the auditory hallucinatory experience (HE)-non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) association (n = 1051) and b parallel mediation model of key mediating variables in the auditory HE-suicide attempt association (n = 1087). Unstandardised effects are reported; 95% confidence intervals are reported in brackets next to estimates; confounders (age, sex, substance use) not shown; AH_baseline auditory hallucinatory experiences at baseline; total_BIS_T1 total Behavioural Inhibition scores at 1-year follow-up (T1). In terms of recent (T1) traumatic life events, of the participants reporting both baseline auditory hallucinatory experiences and incident self-injurious behaviour at T2, 33.3% reported being bullied, 22.2% reported being sexual assaulted, 22.2% reported close friends or family had attempted suicide or deliberately harmed themselves, and 11.1% reported being physically abused at T1

Supplementary mediation models Using MacKinnon et al.'s (2008, 2009) two-wave mediation approach, we found largely consistent results with our three-wave mediation models (see Online Resource 3). Using the first 2 waves of data, we found psychological distress, self-esteem, and recent traumatic life events were all significant single mediators of the association between baseline auditory HEs and incident NSSI/suicide attempts at T1; except for traumatic life events, which was not a significant single mediator of the HE-incident suicide attempt association. In addition, BIS scores were not a significant mediator of the HE-NSSI association; whereas both ERQ cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression significantly mediated the HE-suicide attempt association. All other potentially mediating pathways were non-significant, as consistent with three-wave, single mediation results. Parallel mediation models using the first 2 waves of data found for NSSI models, recent traumatic events and low-self-esteem remained significant mediators of the PE-NSSI association. For suicide attempt models, psychological distress remained a significant mediator of the PE-suicide attempt association.

In terms of the other PE subtypes, their three-wave mediation findings were largely inconsistent with auditory HEs results (data not shown). There were no significant direct or indirect (i.e. mediating) pathways of the thoughts read-NSSI/suicide attempt association. For both special messages and feeling spied-upon, psychological distress and low self-esteem were significant single mediators of the -NSSI and -suicide attempt associations; however, in the parallel mediation models, there were no significant mediating pathways.

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate both the PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt association, and their relevant mediators, across three waves of data. Of all the PE subtypes, auditory HEs were consistently associated with incident NSSI and suicide attempts at the 1- and 2-year follow-up; although some estimates had wide confidence intervals indicating a lack of precision in the estimates, and a potential type II error (see Table 2). This is consistent with our previous results using a nationally representative sample of Australian adolescents [4], as well as the wider literature supporting the important and specific role of hallucinatory experiences in self-harm and suicidal behaviour [12, 16, 66].

Auditory HEs were indirectly associated with future NSSI via psychological distress, low self-esteem, recent traumatic life events, and high BIS scores. Similarly, the auditory HE-suicide attempt association was significantly mediated by distress, self-esteem, recent traumatic life events, and low ERQ cognitive reappraisal. These findings were supported by supplementary two-wave mediation analyses. These results are consistent with the rationale that experiencing PEs produces emotional and behavioural responses (e.g. high levels of distress and negative self-evaluation) that increases the likelihood of self-harming or attempting suicide [66,67,69]. Findings related to low cognitive reappraisal in suicide attempt models, i.e. a tendency to escape or avoid one’s own emotions [52, 70], and high BIS scores in NSSI models, i.e. a sensitivity to and avoidance of stimuli perceived as threatening or punishing [56, 57, 71] are consistent with the wider literature showing young people with PEs report difficulties with coping skills and emotion regulation [8, 14].

When all key mediating variables were included in parallel mediation models, recent traumatic life events remained a significant mediator of the auditory HE-NSSI association; but not the HE-suicide attempt association, albeit with relatively large point estimates (OR range 2.13–2.21; see Fig. 3b). Recent traumatic life experience was the main mediating variable of the auditory HE-NSSI/suicide attempt association, confirming previous proposals that the relation between these two phenomena is not direct, but rather is explained by traumatic life events, particularly interpersonal events with intent to harm [14, 24, 72, 73]. This HE → traumatic life event → NSSI/suicide attempt pathway has face validity as there is robust evidence for these types of traumatic life events (i.e. bullying, sexual assault) preceding self-harm or a suicide attempt among adolescents [73,74,76]. Experiencing auditory HEs, which in themselves are distressing [77], and are often characterised by threat-related content [78], could result in (1) a young person being more vulnerable to experiencing traumatic life events (e.g. increased vulnerability to subsequent victimisation, [49]), and/or (2) interpreting negative interactions with others in a more pessimistic/adverse manner and therefore may be more likely to label such experiences as bullying [23, 48]. It should be noted that the traumatic event variable also included exposure to friend or family self-harm/suicide, which was influential of the auditory HE-suicide attempt association (but not the auditory HE-NSSI association). Adolescents with PEs may live in social circumstances where they are more likely to be exposed to a friend or family member's self-harm/suicide [23]. This may affect a young person’s suicide risk due to the trauma experienced, as well as via other mechanisms such as social transmission of suicide [51]. The differing psychosocial/environmental mechanisms via which PEs are associated with non-suicidal and suicidal behaviours need to be further considered going forward.

Strengths

This cohort study was the first to investigate PE-NSSI and PE-suicide attempt associations across three waves. Most of the PE literature has not investigated NSSI, a critical but often overlooked self-injurious behaviour which is not a suicide attempt per se, but nevertheless increases the risk of suicide death among adolescents [79, 80]. The choice of mediators was driven by a comprehensive approach; including a previous investigation of the individual contribution of several potential mediators using a nationally representative adolescent sample [4]. There was clear establishment of the temporal sequence of events in the three-wave mediation models. This is not often achieved in mediation analyses, and many previous PE studies do not take baseline NSSI/suicide attempts into account when predicting future self-harm and suicide attempts.

Limitations

The sample size, whilst large (n = 1100), was still underpowered for examining low prevalence outcomes such as suicide attempts. This may have resulted in type II errors with true associations being reported as non-significant. Similar to other prospective suicide studies [34] some cell sizes were small, and we recommend caution when interpreting these results. Early child maltreatment could not be investigated using the current dataset, which should be included as a confounder in future studies for a more complete analysis of the PE-self injurious behaviour association. There are well-established links between childhood trauma and auditory HEs [26, 81], and studies have found childhood adversity and recent school life stressors have an interactive (or multiplicative) effect on predicting youth suicidality [82]. Biological and genetic factors were also not included; however, heritability estimates of hallucinations are low [83, 84] indicating the significance of early trauma and other environmental factors in their occurrence [84].

This was not a nationally representative sample of adolescents and generalisability was limited by the high rate of non-response from parents who did not return consent forms. Also, our sample was largely drawn from Catholic schools. We experienced attrition (52.2% of total sample) where those lost to follow-up reported more PEs, self-injurious behaviour, psychological distress, dysfunctional emotion regulation strategies and less behavioural inhibition at baseline, compared to those not lost to follow-up. However, supplementary mediation analyses using only the first 2 waves of data found largely consistent results with the three-wave mediation models (Online Resource 3). All variables were self-reported, with no clinical assessment, and thus prone to measurement error due to misinterpretation of the question and recall bias. Finally, the focus of this study was on the mediators of the association between PEs and self-injurious behaviour. It is of course plausible that traumatic life events precede auditory HEs which in turn could lead to NSSI/suicide attempts. This was beyond the scope of this study. This would be best investigated using a multi-wave dataset of recent measures of all phenomena (as opposed to lifetime measures at each timepoint), and by using particular modelling approaches such as cross-lagged regression [85], which allows for modelling of bidirectional relationships across multiple timepoints, but which has a strict set of assumptions [85,86,88].

Clinical implications

The current findings underscore the importance of screening for auditory HEs when assessing a young person’s self-harm/suicide risk. Other PE subtypes appear to be of less importance in terms of NSSI/suicide attempt risk, where most were not associated with incident NSSI or suicide attempts, either directly or indirectly; although some estimates had wide confidence intervals (Table 2). Clinical assessment of self-harm and suicide risk in young people with PEs would be further enhanced by asking about interpersonal stressors/traumatic events (e.g. bullied, physical or sexual abuse/assault, family/friend suicide), as well as self-esteem and levels of distress. Empathic inquiry about these with appropriate validation may assist in reducing self-harm and suicide risk. Fostering resilience, self-esteem, healthy emotion regulation and coping strategies, and help seeking behaviour among young people with PEs may assist in preventing self-harm and suicide.

Future research

Considering the limited generalisability, our findings require replication in larger, more representative adolescent samples. Future studies should also focus on investigating the potential influence of hallucinatory characteristics (e.g. voice omnipotence and intent), the explanatory value of self-harm/suicidal theories (e.g. Interpersonal Theory of Suicide) in the auditory HE-self injurious association [34], as well as the dynamic nature of the relationship. Previous studies have shown PEs that are more persistent in nature have more robust associations with NSSI and suicide attempts [7, 89], but this has yet to be investigated across three (or more) waves of data.

Conclusions

Auditory HEs were indirectly associated with future NSSI and suicide attempts via recent traumatic life events (being bullied, physically or sexually abused/assaulted, exposed to friend/family self-harm or suicide), high psychological distress, and low self-esteem, across three waves of data. Other PE subtypes were mostly not associated with incident NSSI/suicide attempts at 1- and 2-year follow-up, either directly or indirectly. By identifying relevant and modifiable targets for youth self-harm/suicide prevention and intervention efforts, this prospective cohort study has high clinical utility for young people with PEs.

Data availability

Data available upon request.

Notes

Complete case and imputed data were largely consistent, producing similar parameter estimates for all analyses. Complete case data were reported in the results section.

This item was further revised to include only direct self-injury methods as based on participant qualitative data (e.g. cutting, hitting, scratching).

The evidence favours reappraisal as a strategy for regulating emotions as opposed to suppression [53].

References

Kelleher I, Connor D, Clarke M, Devlin N, Harley M, Cannon M (2012) Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in childhood and adolescence: a systematic review and metaanalysis of population-based studies. Psychol Med 9:1–7

McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Bromet EJ, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-de-Almeida JM, Chiu WT, de Jonge P, Fayyad J, Florescu S, Gureje O, Haro JM, Hu C, Kovess-Masfety V, Lepine JP, Lim CC, Mora ME, Navarro-Mateu F, Ochoa S, Sampson N, Scott K, Viana MC, Kessler RC (2015) Psychotic experiences in the general population: a cross-national analysis based on 31,261 respondents from 18 countries. JAMA Psychiatry 72:697–705

Hielscher E, Connell M, Lawrence D, Zubrick SR, Hafekost J, Scott JG (2018) Prevalence and correlates of psychotic experiences in a nationally representative sample of Australian adolescents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 52:768–781

Hielscher E, Connell M, Lawrence D, Zubrick SR, Hafekost J, Scott JG (2019) Association between psychotic experiences and non-accidental self-injury: results from a nationally representative survey of adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 54:321–330

McGrath JJ, Saha S, Al-Hamzawi A, Andrade L, Benjet C, Bromet EJ, Browne MO, Caldas de Almeida JM, Chiu WT, Demyttenaere K, Fayyad J, Florescu S, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, Haro JM, Ten Have M, Hu C, Kovess-Masfety V, Lim CC, Navarro-Mateu F, Sampson N, Posada-Villa J, Kendler KS, Kessler RC (2016) The bidirectional associations between psychotic experiences and DSM-IV mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry 173:997–1006

Martin G, Thomas H, Andrews T, Hasking P, Scott JG (2015) Psychotic experiences and psychological distress predict contemporaneous and future non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in a sample of Australian school-based adolescents. Psychol Med 45:429–437

Rimvall MK, van Os J, Rask CU, Olsen EM, Skovgaard AM, Clemmensen L, Larsen JT, Verhulst F, Jeppesen P (2019) Psychotic experiences from preadolescence to adolescence: when should we be worried about adolescent risk behaviors? Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01439-w

Kelleher I, Corcoran P, Keeley H, Wigman JT, Devlin N, Ramsay H, Wasserman C, Carli V, Sarchiapone M, Hoven C, Wasserman D, Cannon M (2013) Psychotic symptoms and population risk for suicide attempt: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry 70:940–948

Sullivan SA, Lewis G, Gunnell D, Cannon M, Mars B, Zammit S (2015) The longitudinal association between psychotic experiences, depression and suicidal behaviour in a population sample of adolescents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50:1809–1817

Yates K, Lang U, Cederlof M, Boland F, Taylor P, Cannon M, McNicholas F, DeVylder J, Kelleher I (2019) Association of psychotic experiences with subsequent risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide deaths: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal population studies. JAMA Psychiatry 76:180–189

Cederlöf M, Kuja-Halkola R, Larsson H, Sjölander A, Östberg P, Lundström S, Kelleher I, Lichtenstein P (2017) Longitudinal study of adolescent psychotic experiences and later development of substance use disorder and suicidal behavior. Schizophr Res 181:13–16

Nishida A, Sasaki T, Nishimura Y, Tanii H, Hara N, Inoue K, Yamada T, Takami T, Shimodera S, Itokawa M, Asukai N, Okazaki Y (2010) Psychotic-like experiences are associated with suicidal feelings and deliberate self-harm behaviors in adolescents aged 12–15 years. Acta Psychiatr Scand 121:301–307

DeVylder JE, Hilimire MR (2015) Suicide risk, stress sensitivity, and self-esteem among young adults reporting auditory hallucinations. Health Soc Work 40:175–181

Kelleher I, Lynch F, Harley M, Molloy C, Roddy S, Fitzpatrick C, Cannon M (2012) Psychotic symptoms in adolescence index risk for suicidal behavior: findings from 2 population-based case-control clinical interview studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69:1277–1283

Nishida A, Shimodera S, Sasaki T, Richards M, Hatch SL, Yamasaki S, Usami S, Ando S, Asukai N, Okazaki Y (2014) Risk for suicidal problems in poor-help-seeking adolescents with psychotic-like experiences: findings from a cross-sectional survey of 16,131 adolescents. Schizophr Res 159:257–262

Capra C, Kavanagh DJ, Hides L, Scott JG (2015) Subtypes of psychotic-like experiences are differentially associated with suicidal ideation, plans and attempts in young adults. Psychiatry Res 228:894–898

Ployhart RE, MacKenzie WI (2015) Two waves of measurement do not a longitudinal study make. In: Vandenberg CELRJ (ed) More statistical and methodological myths and urban legends. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group, pp 85–99

Hielscher E, DeVylder JE, Saha S, Connell M, Scott JG (2018) Why are psychotic experiences associated with self-injurious thoughts and behaviours? A systematic review and critical appraisal of potential confounding and mediating factors. Psychol Med 48:1410–1426

Honings S, Drukker M, Groen R, van Os J (2016) Psychotic experiences and risk of self-injurious behaviour in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 46:237–251

Maxwell SE, Cole DA (2007) Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol Methods 12:23–44

Liu J, Ulrich C (2016) Mediation analysis in nursing research: a methodological review. Contemp Nurse 52:643–656

Fairchild AJ, McDaniel HL (2017) Best (but oft-forgotten) practices: mediation analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 105:1259–1271

Kelleher I, Keeley H, Corcoran P, Ramsay H, Wasserman C, Carli V, Sarchiapone M, Hoven C, Wasserman D, Cannon M (2013) Childhood trauma and psychosis in a prospective cohort study: cause, effect, and directionality. Am J Psychiatry 170:734–741

DeVylder JE, Jahn DR, Doherty T, Wilson CS, Wilcox HC, Schiffman J, Hilimire MR (2015) Social and psychological contributions to the co-occurrence of sub-threshold psychotic experiences and suicidal behavior. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 50:1819–1830

DeVylder J, Waldman K, Hielscher E, Scott J, Oh H (2020) Psychotic experiences and suicidal behavior: testing the influence of psycho-socioenvironmental factors. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01841-9

Gaweda L, Pionke R, Krezolek M, Frydecka D, Nelson B, Cechnicki A (2020) The interplay between childhood trauma, cognitive biases, psychotic-like experiences and depression and their additive impact on predicting lifetime suicidal behavior in young adults. Psychol Med 50:116–124

Klonsky ED (2007) The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev 27:226–239

Andover MS, Morris BW (2014) Expanding and clarifying the role of emotion regulation in nonsuicidal self-injury. Can J Psychiatry 59:569–575

Nishida A, Tanii H, Nishimura Y, Kajiki N, Inoue K, Okada M, Sasaki T, Okazaki Y (2008) Associations between psychotic-like experiences and mental health status and other psychopathologies among Japanese early teens. Schizophr Res 99:125–133

Lockwood J, Daley D, Townsend E, Sayal K (2017) Impulsivity and self-harm in adolescence: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 26:387–402

Gvion Y, Apter A (2011) Agression, impulsivity and suicide behavior: a review of the literature. Arch Suicide Res 15:93–112

Koyanagi A, Stickley A, Haro JM (2015) Psychotic-like experiences and nonsuicidal self-injury in england: results from a national survey. PLoS ONE 10:e0145533

Kelleher I, Ramsay H, DeVylder J (2017) Psychotic experiences and suicide attempt risk in common mental disorders and borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 135:212–218

Hielscher E, DeVylder J, Connell M, Hasking P, Martin G, Scott JG (2020) Investigating the role of hallucinatory experiences in the transition from suicidal thoughts to attempts. Acta Psychiatr Scand 141:241–253

Armando M, Nelson B, Yung AR, Ross M, Birchwood M, Girardi P, Fiori Nastro P (2010) Psychotic-like experiences and correlation with distress and depressive symptoms in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Schizophr Res 119:258–265

Yung AR, Buckby JA, Cotton SM, Cosgrave EM, Killackey EJ, Stanford C, Godfrey K, McGorry PD (2006) Psychotic-like experiences in non psychotic help-seekers: associations with distress, depression, and disability. Schizophr Bull 32:352–359

Yung AR, Buckby JA, Cosgrave EM, Killackey EJ, Baker K, Cotton SM, McGorry PD (2007) Association between psychotic experiences and depression in a clinical sample over 6 months. Schizophr Res 91:246–253

Shaffer D, Schwab-Stone M, Fisher P, Cohen P, Piacentini J, Davies M, Conners CK, Regier D (1993) The diagnostic interview schedule for children-revised version (DISC-R): I. Preparation, field testing, interrater reliability, and acceptability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 32:643–650

Poulton R, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Cannon M, Murray R, Harrington H (2000) Children's self-reported psychotic symptoms and adult schizophreniform disorder: a 15-year longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57:1053–1058

Kelleher I, Harley M, Murtagh A, Cannon M (2011) Are screening instruments valid for psychotic-like experiences? A validation study of screening questions for psychotic-like experiences using in-depth clinical interview. Schizophr Bull 37:362–369

Gutierrez PM, Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA (2001) Development and initial validation of the Self-harm Behavior Questionnaire. J Pers Assess 77:475–490

Goldberg DP, Oldehinkel T, Ormel J (1998) Why GHQ threshold varies from one place to another. Psychol Med 28:915–921

Siddique CM, D'Arcy C (1984) Adolescence, stress, and psychological well-being. J Youth Adolesc 13:459–473

Tait RJ, French DJ, Hulse GK (2003) Validity and psychometric properties of the General Health Questionnaire-12 in young Australian adolescents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 37:374–381

Rosenberg M (1965) Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Blascovich J, Tomaka J (1993) Measures of self esteem. In: Robinson JP (ed) Measures of Personality and social psychological attitudes, 3rd edn. Institute for Social Research, Ann Arbor, pp 115–160

Tatnell R, Kelada L, Hasking P, Martin G (2014) Longitudinal analysis of adolescent NSSI: the role of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. J Abnorm Child Psychol 42:885–896

Honings S, Drukker M, Ten Have M, de Graaf R, van Dorsselaer S, van Os J (2017) The interplay of psychosis and victimisation across the life course: a prospective study in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52:1363–1374

Bhavsar V, Dean K, Hatch SL, MacCabe JH, Hotopf M (2019) Psychiatric symptoms and risk of victimisation: a population-based study from Southeast London. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 28:168–178

Hawton K, Rodham K (2006) By their own young hand-deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideas in adolescents. Jessica-Kingsley, London

Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC (2012) Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet 379:2373–2382

Gross JJ, John OP (2003) Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 85:348–362

Butler EA, Egloff B, Wilhelm FH, Smith NC, Erickson EA, Gross, JJ (2003) The social consequences of expressive suppression. Emotion 3:48–67. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.48

Dawkins JC, Hasking PA, Boyes ME, Greene D, Passchier C (2019) Applying a cognitive-emotional model to nonsuicidal self-injury. Stress Health 35:39–48

Gray JA (1981) A critique of Eysenck's theory of personality. In: Eysenck HJ (ed) A model for personality. Springer, Berlin, pp 246–276

Ammerman BA, Kleiman EM, Jenkins AL, Berman ME, McCloskey MS (2017) Using propensity scores to examine the association between behavioral inhibition/activation and nonsuicidal and suicidal self-injury. Crisis 38:227–236

Cerutti R, Presaghi F, Manca M, Gratz KL (2012) Deliberate self-harm behavior among Italian young adults: correlations with clinical and nonclinical dimensions of personality. Am J Orthopsychiatry 82:298–308

Carver CS, White TL (1994) Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS Scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 67:319–333

Tanner A, Hasking P, Martin G (2016) Co-occurring non-suicidal self-injury and firesetting among at-risk adolescents: experiences of negative life events, mental health problems, substance use, and suicidality. Arch Suicide Res 20:233–249

Mertler CA, Vannatta RA (2013) Advanced and multivariate statistical methods: practical application and interpretation, 5th edn. Pyrczak, Glendale

MacKinnon DP (2008) Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Erlbaum, Mahwah

Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF (2007) Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav Res 42:185–227

Cole DA, Maxwell SE (2003) Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. J Abnorm Psychol 112:558–577

Mackinnon DP, Fairchild AJ (2009) Current directions in mediation analysis. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 18:16

DeVylder JE, Kelleher I (2016) Clinical significance of psychotic experiences in the context of sleep disturbance or substance use. Psychol Med 46:1761–1767

Thompson E, Spirito A, Frazier E, Thompson A, Hunt J, Wolff J (2020) Suicidal thoughts and behavior (STB) and psychosis-risk symptoms among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Schizophr Res 218:240–246

Fialko L, Freeman D, Bebbington PE, Kuipers E, Garety PA, Dunn G, Fowler D (2006) Understanding suicidal ideation in psychosis: findings from the psychological prevention of relapse in psychosis (PRP) trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand 114:177–186

Grano N, Salmijarvi L, Karjalainen M, Kallionpaa S, Roine M, Taylor P (2015) Early signs of worry: psychosis risk symptom visual distortions are independently associated with suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Res 225:263–267

Forman EM, Berk MS, Henriques GR, Brown GK, Beck AT (2004) History of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioral marker of severe psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry 161:437–443

Eftekhari A, Zoellner LA, Vigil SA (2009) Patterns of emotion regulation and psychopathology. Anxiety Stress Coping 22:571–586

Daniel SS, Goldston DB, Erkanli A, Franklin JC, Mayfield AM (2009) Trait anger, anger expression, and suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults: a prospective study. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 38:661–671

DeVylder JE (2018) Letter to the editor: cumulative trauma as a potential explanation for the elevated risk of suicide associated with psychotic experiences: commentary on Moriyama et al. ‘The association between psychotic experiences and traumatic life events’. Psychol Med 48:1915–1916

Narita Z, Wilcox HC, DeVylder J (2020) Psychotic experiences and suicidal outcomes in a general population sample. Schizophr Res 215:223–228

Guerreiro DF, Sampaio D, Figueira ML, Madge N (2017) Self-harm in adolescents: a self-report survey in schools from Lisbon, Portugal. Arch Suicide Res 21:83–99

Madge N, Hawton K, McMahon EM, Corcoran P, De Leo D, de Wilde EJ, Fekete S, van Heeringen K, Ystgaard M, Arensman E (2011) Psychological characteristics, stressful life events and deliberate self-harm: findings from the child and adolescent self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 20:499–508

Kaess M, Eppelmann L, Brunner R, Parzer P, Resch F, Carli V, Wasserman C, Sarchiapone M, Hoven CW, Apter A, Balazs J, Barzilay S, Bobes J, Cosman D, Horvath LO, Kahn JP, Keeley H, McMahon E, Podlogar T, Postuvan V, Saiz PA, Tubiana A, Varnik A, Wasserman D (2020) Life events predicting the first onset of adolescent direct self-injurious behavior-a prospective multicenter study. J Adolesc Health 66:195–201

Brett C, Heriot-Maitland C, McGuire P, Peters E (2014) Predictors of distress associated with psychotic-like anomalous experiences in clinical and non-clinical populations. Br J Clin Psychol 53:213–227

Freeman D (2007) Suspicious minds: the psychology of persecutory delusions. Clin Psychol Rev 27:425–457

Mars B, Heron J, Klonsky ED, Moran P, O'Connor RC, Tilling K, Wilkinson P, Gunnell D (2019) Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry 6:327–337

Grandclerc S, De Labrouhe D, Spodenkiewicz M, Lachal J, Moro MR (2016) Relations between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior in adolescence: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 11:e0153760

Daalman K, Diederen KM, Derks EM, van Lutterveld R, Kahn RS, Sommer IE (2012) Childhood trauma and auditory verbal hallucinations. Psychol Med 42:2475–2484

You Z, Chen M, Yang S, Zhou Z, Qin P (2014) Childhood adversity, recent life stressors and suicidal behavior in Chinese college students. PLoS ONE 9:e86672

Sieradzka D, Power RA, Freeman D, Cardno AG, Dudbridge F, Ronald A (2015) Heritability of individual psychotic experiences captured by common genetic variants in a community sample of adolescents. Behav Genet 45:493–502

Zavos HM, Freeman D, Haworth CM, McGuire P, Plomin R, Cardno AG, Ronald A (2014) Consistent etiology of severe, frequent psychotic experiences and milder, less frequent manifestations: a twin study of specific psychotic experiences in adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 71:1049–1057

Hernandez DC, Johnston CA (2016) Unidirectional or bidirectional relationships of behaviors: the importance of positive behavioral momentum. Am J Lifestyle Med 10:381–384

Mu W, Luo J, Rieger S, Trautwein U, Roberts B (2019) The relationship between self-esteem and depression when controlling for neuroticism. Collabra Psychol 5:1–13

Berry D, Willoughby MT (2017) On the practical interpretability of cross-lagged panel models: rethinking a developmental workhorse. Child Dev 88:1186–1206

Hamaker EL, Kuiper RM, Grasman RP (2015) A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychol Methods 20:102–116

Connell M, Betts K, McGrath JJ, Alati R, Najman J, Clavarino A, Mamun A, Williams G, Scott JG (2016) Hallucinations in adolescents and risk for mental disorders and suicidal behaviour in adulthood: prospective evidence from the MUSP birth cohort study. Schizophr Res 176:546–551

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the young people who participated in the survey.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Australian Research Council, Discovery Grant (project 0985470). EH is supported by the Dr F and Mrs ME Zaccari Scholarship, Australia. JGS is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship Grant (grant number 1105807).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by Monash University and The University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committees and has therefore been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Consent was provided by school principals, parents, and students.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hielscher, E., DeVylder, J., Hasking, P. et al. Mediators of the association between psychotic experiences and future non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts: results from a three-wave, prospective adolescent cohort study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30, 1351–1365 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01593-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01593-6