Abstract

This paper analyzes the location (at home or abroad) and the mode of organization (outsourcing versus integration) of intermediate inputs production, using data on a sample of Italian manufacturing companies and focusing on the role of firm heterogeneity. We find evidence of a productivity ordering where foreign integration is chosen by the most productive firms and domestic outsourcing is chosen by the least productive firms; firms with medium-high productivity choose domestic integration, firms with medium-low productivity choose foreign outsourcing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the last decades the strong growth of trade in intermediate inputs and the rise in foreign direct investment (FDI) have been major features of international trade. A useful conceptual framework to address these issues is the assumption that a firm which needs an intermediate input is faced with a two-dimensional choice: it has to decide where the good should be produced (at home or abroad) and how it should be produced (in-house or outsourced to another firm). The combination of these two choices yields four possibilities: an input can be produced in the home country, either in-house (domestic integration) or by outsourcing (domestic outsourcing), or it can be produced in a foreign country, again either in-house (foreign integration or FDI) or by outsourcing (foreign outsourcing). As argued by Helpman (2006a), “an understanding of what drives these choices is essential for an understanding of the recent trends in the world economy”.

Several theoretical models, at the crossroads of industrial organization and international trade, have been developed (Antràs 2003; Antràs and Helpman 2004, 2008; Grossman and Helpman 2004). Despite a rich set of predictions, the empirical literature is far from abundant and provides only partial and incomplete pictures of sourcing strategies. Using trade data, some studies look at intra-firm imports as a proxy of the preference for FDI over foreign outsourcing (Antràs 2003; Yeaple 2006; Nunn and Trefler 2008; Bernard et al. 2008). This literature, however, does not take into account domestic production (either by integration or outsourcing), as trade data do not record domestic transactions. Very few studies use firm-level data (Tomiura 2007; Defever and Toubal 2007), but they suffer from the same limitation, that is they do not provide any information on inputs purchased from domestic suppliers. Two related strands of literature look at the effects of imported intermediate inputs on productivity (Amiti and Konings 2007; Kasahara and Rodrigue 2008; Görg et al. 2008) or at importers’ productivity premia (Bernard et al. 2007; Castellani et al. 2008; Muuls and Pisu 2009), respectively. These studies, however, consider only the location of production, but not the organization of production: no distinction is made indeed between intra-firm and arm’s-length imports.

This paper contributes to the literature by simultaneously taking into account both the location and the organization of production of intermediate inputs. Using detailed information on the sourcing strategies adopted by a sample of Italian manufacturing firms, we are able to observe the four organizational forms mentioned above (domestic integration, domestic outsourcing, foreign integration and foreign outsourcing). The structure of our data closely matches the Antràs and Helpman (2004) model, allowing for a rigorous test of its predictions on the role of firm heterogeneity. Furthermore, our data on intermediate inputs only include inputs produced within a “subcontracting” relationship, i.e. according to the specifications of the buying company. Therefore, in contrast to the large majority of previous studies, our data exclude raw materials and standardized or “generic” inputs bought on a spot market. This is fully consistent with theory, which usually assumes that the supplier is required to undertake relationship-specific investments in order to produce the goods needed by the firm.

To our knowledge, this is the first paper which reports firm-level evidence for the four organizational forms at the same time. This goes exactly in the direction suggested, among others (Greenaway and Kneller 2007; Helpman 2006b), by Bernard et al. (2007, p. 128): “Further progress [...] will require explicit consideration of the boundaries of the firm, including the decisions about whether to insource or outsource stages of production, and whether such insourcing or outsourcing takes place within or across national boundaries”.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a review of related literature and Sect. 3 describes the data. Section 4 reports empirical results, while Sect. 5 concludes.

2 Related literature

Theories on the choice between integration and outsourcing are mainly based on the property rights approach (for surveys see Spencer 2005; Helpman 2006b; Antràs and Rossi-Hansberg 2008). Production of a final good requires two intermediate inputs, which are assumed to be specific for a particular production and cannot be used outside that production. One of the two inputs can only be provided by the final-good producer at home; as regards the other input, the producer decides where to locate its production (at home or abroad) and whether to make it in-house or buy it from an independent supplier. The supplier has to undertake a relationship-specific investment in order to specialize the production to the buyer’s needs. However, the level of investment cannot be specified in the contract between the supplier and the buyer. The assumption of incomplete contracting leads to a situation in which the provision of both inputs is below the level which would be attained if contracts were complete, because the threat of contractual breach reduces each party’s incentive to invest (hold-up problem). An efficient solution would generally imply that the party which contributes the most to the value of the relationship through its investment should own the residual rights of control. Integration arises when production is very intensive in the input provided by the final-good producer. By contrast, when the contribution of the other input is very significant, outsourcing the production of the input to the supplier will be optimal (Antràs 2003; Antràs and Helpman 2004).

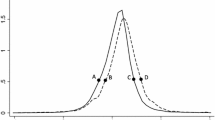

By introducing heterogeneous firms in this setting, predictions on how the choice of the organizational form is related to firms’ characteristics can be made. In the work of Melitz (2003), the assumption that exports require fixed costs determines a selection mechanism by which exporting is profitable only for the most productive firms. A similar reasoning leads to the assumption that participation in international activities (foreign integration or outsourcing) entails high fixed costs, and is thus viable only for the most productive firms. Starting from this assumption, and also supposing that fixed costs of integration are higher than fixed costs of outsourcing, Antràs and Helpman (2004) show that productivity ranking determines the firm’s choice: specifically, in sectors with high headquarter intensity, foreign integration is chosen by the most productive firms, while firms with medium-high productivity prefer foreign outsourcing, firms with medium-low productivity prefer domestic integration, and the least productive firms prefer domestic outsourcing. In sectors with low headquarter intensity, where producing the component abroad yields a larger advantage, only two organizational forms remain: foreign outsourcing (for less productive firms) and foreign integration (for more productive firms).

These findings, however, depend crucially on specific assumptions about fixed costs. For instance, Antràs and Helpman (2004) show that if the ordering of organizational fixed costs were inverted and outsourcing became more costly than integration, then the most productive firms would choose to outsource abroad, while less productive firms would opt for foreign integration; lower-productivity firms would outsource at home and domestic integration would be chosen by the least productive firms (Table 1). In the case of economies of scope in management, assuming lower fixed costs of integration is more appropriate, because a joint supervision of input production and other activities is more convenient; conversely, when there are significant costs related to managerial overload the assumption of lower fixed outsourcing costs seems more correct.

In a different setting, the relationship between organizational form and firm productivity is even more complex. Grossman and Helpman (2004) put forth a “managerial incentives” model of international organization of production. The production of a differentiated good by a principal requires a component or a service which can only be provided by a skilled agent. The agent may act as an independent supplier or as a “division” of the principal. There is a trade-off between the stronger incentives (in the case of an independent supplier) and the greater monitoring allowed by vertical integration. The authors find that foreign outsourcing is chosen by the most productive and the least productive firms, while intermediate-productivity firms choose to integrate. The intuition is that at the two ends of the productivity spectrum there is a greater need to induce a high level of effort in the agent, whose incentives will be stronger if he acts independently; in the middle range the ability to monitor the agent’s efforts weighs more in raising potential revenues.

Given the extent to which the various assumptions and models influence the predictions, empirical evidence is definitely needed to discriminate between them. Using industry-level data, Yeaple (2006) and Bernard et al. (2008) show that intra-firm trade is higher in industries with greater productivity dispersion. Nunn and Trefler (2008) confirm this finding, adding that the positive relationship between intra-firm and productivity is stronger for high values of headquarter intensity, as predicted by Antràs and Helpman (2004). Among firm-level studies, Tomiura (2005) analyzes a wide database on Japanese manufacturing firms and highlights a large heterogeneity: less than 3% of firms are involved in foreign outsourcing. He finds a positive correlation between the ratio of foreign outsourcing to sales, on the one hand, and productivity or size on the other. In a follow-up paper (Tomiura 2007), the analysis is extended to the choice between international outsourcing and FDI. The results show that organizational forms follow a productivity ordering which is consistent with the predictions of Antràs and Helpman (2004): the most productive firms engage in FDI, less productive firms choose international outsourcing and domestic firms are the least productive. This productivity ordering holds even when firm size, capital intensity and industry are controlled for. A reverse ranking, where more productive firms are less likely to source from affiliate suppliers, is found instead by Defever and Toubal (2007). Their sample (which includes only multinational firms, i.e. that control at least 50% of the equity capital of a foreign affiliate) might help explaining these findings. Footnote 1

3 Data

3.1 Sample

Our firm-level data come from the “Survey on Italian Manufacturing Firms”, conducted every 3 years by Mediocredito Capitalia (MCC). We use the 7th wave of the survey, carried out in 1998, in which information about firms’ sourcing strategies—the core of our analysis—was collected. Footnote 2 The survey covers the 3 years immediately prior (1995–1997), although some parts of the questionnaire only refer to 1997. Balance sheet data are available for the years 1989–1997. The sampling design includes all firms with a minimum of 500 employees. Firms whose employees range from 10 to 500 were selected according to three stratification criteria: geographical area, sector and firm size. In the 1998 survey the total number of firms is 4,497. After dropping the firms for which balance sheet data or other important variables were not available, we eventually had 3,976 observations (around 4% of the universe of Italian firms with a minimum of 10 employees, according to the 2001 census data). The coverage ratio, however, rises to 12.4% for firms with a minimum of 50 employees and 24.8% for firms with a minimum of 200 employees.

Table 2 shows that sample distribution in the various geographical areas and sectors is consistent with the distribution of reference population. Firms located in the North-West and firms operating in the “chemicals, rubber and plastic” sector are slightly over-represented in the sample, the inverse being true for firms located in the South and Islands, and for firms operating in the “textile, clothing and shoes” sector. In terms of firm size, the sample is somewhat unbalanced in favour of medium and large firms.

3.2 Subcontracting

The MCC database provides information on the incidence of subcontracting on total purchases of goods and services, as well as on the type of suppliers. In the Italian legal system, subcontracting is referred to as “a contract by which an entrepreneur engages itself on behalf of the buying company to carry out workings on semifinished products or raw materials, or to supply products or services to be incorporated or used in the buying company’s economic activity or in the production of a complex good, in conformity with the buying company’s projects, techniques, technologies, models or prototypes” (Law 192/1998, italics added). Our definition of subcontracting therefore excludes the purchase of standardized goods or raw materials, in line with the notion used in the theoretical literature.

The theoretical models assume indeed that the supplier must undertake relationship-specific investments in order to produce the goods needed by the firm. A quotation from Grossman and Helpman (2005, p. 136) is illustrative of the point: “To us, outsourcing means more than just the purchase of raw materials and standardized goods. It means finding a partner with which a firm can establish a bilateral relationship and having the partner undertake relationship-specific investments so that it becomes able to produce goods or services that fit the firm’s particular needs”. In fact, with the exception of Tomiura (2005, 2007), empirical literature has been forced by data limitations to use a wider definition of outsourcing, ranging from imports of all—intermediate and final—goods (Antràs 2003; Yeaple 2006; Nunn and Trefler 2008) to raw materials and components (Kurz 2006) or processing exports (Feenstra and Spencer 2005).

Using our firm-level data we are able to identify four types of suppliers (and, correspondingly, four organizational forms, indicated in brackets): affiliates located in Italy (domestic integration); affiliates located abroad (foreign integration); non-affiliates located in Italy (domestic outsourcing); non-affiliates located abroad (foreign outsourcing). These organizational match very closely those usually accounted for in the literature, allowing for a rigorous test of theoretical predictions. As a matter of fact, a fifth organizational form emerges from our data, that is to say when the incidence of subcontracting is zero. Although this could be interpreted as a form of domestic integration in which all transactions occur within the same firm, we think it preferable to consider it as a specific organizational scheme (no sourcing). There are two reasons for this: first, their number is quite high (about two thirds of the total amount of firms); second, no-sourcing firms are markedly different from domestic-integration firms, in terms of industry-level and firm-level characteristics.

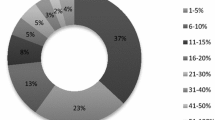

Table 3 shows that about 1.2% of firms in the sample purchased at least some inputs from foreign affiliates, while 6.8% of firms purchased at least some inputs from foreign non-affiliates. As a comparison, Tomiura (2007) finds that the number of foreign-outsourcing firms was equal to 2.7%. The difference is likely due to the bias in favour of medium-large firms of our sample. The usage of foreign inputs varies considerably across industries. Foreign integration is more widespread in the “chemicals, rubber and plastic” industry and in the “metals and mechanical” industry; the latter ranks high also as far as foreign and domestic outsourcing are concerned, followed by the “textile, clothing, shoes” industry. In terms of firm size, there seems to be a positive monotonic relationship, except for domestic outsourcing, which reaches its peak in the 200–499 employees category.

The recourse to mixed sourcing strategies (for instance, buying inputs simultaneously from affiliates and non-affiliates, or from domestic and foreign suppliers) is not infrequent. In particular, there is a strong correlation at the industry level between domestic outsourcing and foreign outsourcing: sectors with a high share of domestic outsourcing also tend to have a high share of foreign outsourcing. Grossman et al. (2005) maintain that this is the case with those industries where the fixed cost of outsourcing is very low.

3.3 Productivity

We compute several measures of firm-level productivity. This variable plays a crucial role in the study of within-industry heterogeneity and the fixed costs of the various organizational forms. Looking at several measures of productivity, we are able to check the robustness of our results to alternative methods and assumptions. We start with the simplest measure: the log of value added per worker (VA i /L i ). We then consider those measures which are based on the estimation of the production function. TFPi,OLS is computed as the residuals from an OLS estimation of a standard Cobb-Douglas, with labour and capital as factors. As an alternative measure, we run a fixed-effects estimation and get the (constant over time) residuals for each firm (TFPi,FE). Our fourth and final measure (TFPi,LP) tackles the simultaneity bias in OLS estimations of the production function estimation. The reason of simultaneity bias is the correlation between input levels and the (unobservable) productivity shock. A positive productivity shock leads the firm to increase output, thereby increasing input levels. As suggested by Levinsohn and Petrin (2003), we employ an observable proxy variable (intermediate inputs) that reacts to variations in the productivity level.

Table 4 displays the correlation matrix of the four productivity variables, together with two different size indicators (logs of value added and employment). Size indicators were added since their use as a proxy for productivity has not been infrequent in the literature (Helpman et al. 2004; Yeaple 2006). Despite the different methods used, productivity estimates are quite similar to each other. The correlation across observations of the four measures goes from a minimum of 0.56 to a maximum of 0.86. Size indicators are, instead, less strongly correlated with productivity measures, in line with the evidence reported by Head and Ries (2003).

4 Empirical evidence

4.1 Main results

The aim of our econometric analysis is to determine whether there are systematic productivity differences among firms depending on their sourcing strategy. We adapt the methodology used for the comparison between exporters and non-exporters in Bernard and Jensen (1999) and in many subsequent papers. We run OLS estimates of the following equation:

where Y i is an indicator of productivity for firm i, FI i , FO i and DI i are dummies for each sourcing strategy (relatively to the group of domestic-outsourcing firms, which is the baseline category). The regression includes a set of 2-digit industry dummies, area dummies and an export status dummy. The coefficients of interest are β1, β2 and β3 which give the average difference in firms’ characteristics between firms with a given sourcing strategy relatively to domestic-outsourcing firms, conditional on the other regressors. Footnote 3

As mentioned in the previous section, in our sample firms typically follow mixed strategies, for instance buying inputs from domestic and foreign suppliers at the same time. This behavior can be easily explained if we assume that firms usually need several inputs and choose the optimal organizational form for each input. Issues about the most appropriate way to deal with mixed strategies arise in our regression framework. We start by assigning firms to a given organizational form on the basis of the following schemes: firms buying domestic outsourcing inputs but no domestic-integration nor foreign outsourcing/integration inputs (DO, or baseline category); firms buying at least some domestic-integration inputs but no foreign outsourcing/integration inputs (DI); firms buying at least some foreign-outsourcing inputs but no foreign-integration inputs (FO); firms buying at least some foreign-integration inputs (FI). The advantage of this classification is that it allows for a more clear-cut identification of each organizational form, including FI (for which the number of active firms is relatively small and the incidence of mixed strategies is large). Our results are, however, robust also to an alternative classification method, as we will show later in this section.

By looking at Table 5, which reports the results obtained if we control for area, industry and export status, we may notice that all the coefficients on the three dummies (FI, FO and DI) are positive and significant at the 10% level. Foreign-integration, foreign-outsourcing and domestic-integration firms are thus larger and more productive than the baseline group of domestic-outsourcing firms. Size premia are larger than productivity premia, as it would be expected if larger firms tended to be more productive. The magnitude of the coefficients is highest for FI, lowest for FO, and it is at an intermediate level for DI. It should be noted that these results do not depend on industry composition, nor on firms’ export status, as we these variables are already controlled for. If they were not, size and productivity differences would be even higher. The next three rows show p-values of tests of equality between couples of coefficients on sourcing dummies. We always reject the hypothesis that foreign-outsourcing firms are as productive as foreign-integration firms and (with only one exception) the hypothesis that they are as productive as domestic-integration firms. In most cases we also reject the hypothesis that domestic-integration firms are as productive as foreign-integration firms. The goodness of fit of our model shows a large variability depending on the measure of size or productivity (see Görg et al. 2008 for similar evidence); for the most structural indicator (TFP à la Levinsohn and Petrin 2003), the R-squared is as high as .62.

These results are, to a large extent, consistent with the productivity ordering assumed by Antràs and Helpman (2004), where foreign-integration firms are at the top of the productivity distribution and domestic-outsourcing firms are at the bottom. In contrast to their assumptions, however, we find that foreign-outsourcing firms are less, and not more, productive than domestic-integration firms. These findings suggest that, for the firms of our sample, fixed costs of foreign sourcing are larger than fixed costs of domestic sourcing and fixed costs of integration are larger than fixed costs of outsourcing. The latter difference is quantitatively so noteworthy in our data, that it overcomes the difference in fixed costs of foreign sourcing.

4.2 Robustness analysis

This section assesses the robustness of our findings. As a first step, we control for several firm-level indicators of skills and innovation, which could have a positive impact on productivity. Our data allow us to build the following five variables: the share of non-production workers (White collars), the share of R&D expenditure on sales (R&D) and three dummies for investments in ICT hardware or software (ICT investments), introduction of new products (Product innovation) or new processes (Process innovation) over the previous 3 years. In Table 6 we include them among the explanatory variables.Footnote 4 As expected, the coefficients on these variables are almost always positive and sometimes statistically significant. The goodness of fit also increases noticeably. After introducing such variables, the coefficients on sourcing dummies are slightly smaller, but are still significantly different from zero in each specification (except for the foreign-outsourcing dummy in two out of six specifications).

Table 7 reports the results if firm size is included among the control variables. The variability of sourcing premia among TFP is now greatly reduced. The productivity differentials, however, keep being statistically significant and quantitatively large. Foreign-integration firms tend to be 18–27% more productive than domestic-outsourcing firms; the differential is around 11–17% for domestic-integration firms and 5–8% for foreign-outsourcing firms, always relatively to domestic-outsourcing firms. The results on equality tests are similar to the previous ones, except for the equality between FI and DI, which is not rejected.

In Table 8 we test the robustness of our results to two alternative assumptions. First, we include the set of no-sourcing firms, which now becomes the baseline category relative to which the productivity premia are computed. Second, we modify our sourcing dummies in order to allow for mixed strategies. Each sourcing dummy now equals one if firms buy at least a positive amount of inputs according to that sourcing strategy. Two or more sourcing dummies may then be simultaneously positive for the same firm. Controlling for area, industry and export status, the results are confirmed, as the coefficients on FI, DI and FO are significantly positive, with decreasing magnitude. There is, instead, no statistically significant difference in terms of size or productivity between domestic-outsourcing firms and no-sourcing firms. p-values on equality tests also provide further support to the previous findings.

Our evidence on productivity differentials is obtained as an average across all manufacturing sectors. It would be interesting to see whether different sectors exhibit different productivity rankings. This would be the case if the relative importance of forces leading to integration (e.g. economies of scope in management) and forces leading to outsourcing (e.g. managerial overload, suppliers’ incentives) varies across industries. We split the sample in two groups: industries producing traditional goods (identified on the basis of Pavitt classification) and other industries. Using finer classifications is unfortunately not feasible, given the size of the sample. Unreported estimates show that the productivity ranking is similar in both groups, while there are differences in the magnitude of productivity differentials. The coefficient on FI is indeed larger in traditional sectors than in the other sectors, while the opposite is observed for DI. This would seem to point to differences in the relative fixed cost of integration between the two sectors: firms in traditional sectors would face a higher fixed cost of integration abroad than firms in other sectors, but a lower fixed cost of integration at home. Further evidence, possibly based on larger samples, is however, needed in order to draw firm conclusions on this issue.

4.3 Endogeneity

Our results show that there are systematic patterns between firm productivity and sourcing strategies, but—being based on a cross-section—do not say anything on the direction of causality. This section provides a discussion of the potential channels of causation and presents further empirical evidence on the issue.

On the one hand, the direction of causality may run from firm productivity to sourcing strategies, as long as the latter imply different fixed costs and firms differ in their productivity levels. Firms would then self-select in a given organizational form, depending on their productivity level. If, for instance, fixed costs of foreign integration are very high, only the most productive firms will be able to bear them and choose to produce through foreign integration, while less productive firms will opt for less expensive organizational forms. This is analogous to the self-selection hypothesis in the literature on exporting and productivity.

On the other hand, the direction of causality may run the other way round, that is from sourcing strategies to firm productivity. In particular, foreign sourcing may lead to increased productivity in various ways. First, there could be a learning mechanism by which contacts with foreign suppliers allow firms to improve their products. Second, operating with foreign suppliers could give access to higher-quality inputs or to inputs which are simply not available from domestic suppliers. A third channel is suggested by Glass and Saggi (2001). In their model, foreign sourcing lowers marginal costs of production and increases profits, thus providing greater incentives for innovation. This in turn may lead to higher productivity for firms with foreign suppliers. These potential explanations are, however, only partially consistent with our findings, in which domestic-integration firms turn out to be more (and not less) productive than foreign-outsourcing firms.

There is an other channel by which sourcing strategy may have an impact on firm productivity. Firms might choose to outsource the production of non-core activities, in order to focus on those activities in which they have a competitive advantage. Then outsourcing would determine an increase in productivity. This explanation too is not consistent with our evidence, which suggests that outsourcing firms are less productive than integration firms.

The main point of this discussion is that, if causality runs from sourcing strategies to firm productivity, then we would expect a productivity ranking that is only partially consistent with what we actually observe in our data. On this basis the alternative interpretation, namely the self-selection hypothesis, would seem more likely.

For further insights on the causality issue it is necessary to turn to the empirical evidence. Unfortunately, data on sourcing strategies are only available on a cross-section basis. This prevents us from running the usual tests of causality based on time-series information on entry to or exit from a given organizational form. For almost two thirds of the firms in our sample, however, we have time-series information on productivity. We are able to compute the growth rate of productivity between 1992 and 1997 and regress it on the sourcing dummies in 1997. We also regress the productivity level in 1992 on the sourcing dummies in 1997 (similarly to Baldwin and Gu 2003 for export premia). The idea behind this test is that, if firms differ ex ante, then we should already see differences in productivity levels a few years before sourcing is observed. The learning channel implies instead that firms, starting with similar levels of productivity, experience different growth rates of productivity.Footnote 5

The upper panel of Table 9 shows that firms with different sourcing strategies in 1997 do not show any difference in terms of the growth rate of productivity over the previous 5 years. If we look instead at the level of productivity in 1992, sourcing dummies in 1997 become once again statistically significant in most specifications, showing a productivity ranking similar to our previous results.Footnote 6 These findings do not provide much support to the learning hypothesis, while they are somewhat more consistent with the self-selection hypothesis, showing persistent differences in productivity levels. This is also in line with the insights arising from the conceptual discussion. Much caution is warranted, however, given the data limitations which prevent us from carrying out a richer empirical analysis of the causality issue.

5 Concluding remarks

Using data on a sample of Italian manufacturing companies, this paper provides evidence on the choice between outsourcing and integration at home and abroad, focusing on the role of firm heterogeneity. We find evidence of statistically significant productivity differentials among firms with different sourcing strategies, controlling for industry, area and export status. Specifically, there seems to be a productivity ordering by which foreign-integration firms are the most productive ones, and domestic-outsourcing firms are the least productive ones, as assumed by Antràs and Helpman (2004). However, in contrast to their assumptions, we also find that foreign-outsourcing firms are less, and not more, productive than domestic-integration firms. This suggests a relatively high fixed cost of integration, which more than offsets the fixed cost of operating with foreign suppliers.

Two main caveats apply. The first is that we are not able to draw strong conclusions on whether productivity differentials reflect ex-ante selection or ex-post learning, although it is fair to say that this issue is common to much of the empirical literature on firm heterogeneity. The second is that these findings should not be taken as evidence that one organizational form is optimal while another organizational form is not optimal or less preferable. We believe nonetheless that our results provide valuable insights for the understanding of aggregate phenomena. For instance, they imply that the Italian manufacturing industry should show a preference for outsourcing over FDI, relatively to other EU countries’ industries, given Italian firms’ smaller average size. More generally, as argued by Antràs and Rossi-Hansberg (2008), firms’ organizational decisions often interact with technology or institutional factors, such as the quality of the legal environment, which lead to different economic outcomes. Although less investigated, their dynamic implications may also be potentially significant, in terms of the evolution of economic activity, skills and knowledge.

Notes

After completing this paper, I became aware of research by Kohler and Smolka (2009), who use firm-level data for Spain with a similar structure to our data. They find that higher-productivity firms are more likely to acquire inputs from a vertically integrated supplier. This effect is stronger for high levels of capital intensity.

Unfortunately, the following waves of MCC surveys did not include questions on firms’ sourcing strategies. Such information was generally missing in other firm-level databases too. The results reported in this paper cannot therefore be taken as evidence on the most recent trends of the Italian economy.

The regression should not be thought of as a structural model, in which productivity is actually caused by explanatory variables. It should rather be interpreted as a way to get conditional means, i.e. the average productivity premia (or discounts) for firms following a given organizational form, relatively to other firms and conditional on a set of factors. The reader is referred to Sect. 4.3 for a discussion of endogeneity issues.

Data on skills and innovation are not available for 9.0% of firms in our sample (119 out 1,316 firms).

Unfortunately there is no information on productivity after 1997 in our data.

The results are robust to changes in the period over which the growth rate of productivity and its lagged level are measured.

References

Amiti M, Konings J (2007) Trade liberalization, intermediate inputs and productivity: evidence from Indonesia. Am Econ Rev 97(5):1611–1638

Antràs P (2003) Firms, contracts and trade structure. Q J Econ 118:1375–1418

Antràs P, Helpman E (2004) Global sourcing. J Polit Econ 112:552–580

Antràs P, Helpman E (2008) Contractual frictions and global sourcing. In: Helpman E, Marin D, Verdier T (eds) The organization of firms in a global economy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Antràs P, Rossi-Hansberg E (2008) Organizations and trade. NBER Working Paper, no. 14262

Baldwin JR, Gu W (2003) Export-market participation and productivity performance in Canadian manufacturing. Can J Econ 36(3):634–657

Bernard AB, Jensen JB (1999) Exceptional exporter performance: cause, effect or both? J Int Econ 47:1–25

Bernard AB, Jensen JB, Redding SJ, Schott PK (2007) Firms in international trade. J Econ Perspect 21(3):105–130

Bernard AB, Jensen JB, Redding SJ, Schott PK (2008) Intra-firm trade and product contractibility. Unpublished paper

Castellani D, Serti F, Tomasi C (2008) Firms in international trade: importers and exporters heterogeneity in the Italian manufacturing industry. LEM Working Paper, no. 4

Defever F, Toubal F (2007) Productivity and the sourcing modes of multinational firms: evidence from French firm-level data. CEP Discussion Paper, no. 842

Feenstra RC, Spencer BJ (2005) Contractual versus generic outsourcing: the role of proximity. NBER Working Paper, no. 11885

Glass AJ, Saggi K (2001) Innovation and wage effects of international outsourcing. Eur Econ Rev 45:67–86

Görg H, Hanley A, Strobl E (2008) Productivity effects of international outsourcing: evidence from plant-level data. Can J Econ 41(2):670–688

Greenaway D, Kneller R (2007) Firm heterogeneity, exporting and foreign direct investment. Econ J 117:F134–161

Grossman G, Helpman E (2004) Managerial incentives and the international organization of production. J Int Econ 63:237–262

Grossman G, Helpman E (2005) Outsourcing in a global economy. Rev Econ Stud 72:135–159

Grossman G, Helpman E, Szeidl A (2005) Complementarities between outsourcing and foreign sourcing. Am Econ Rev Papers Proc 95:19–24

Head K, Ries J (2003) Heterogeneity and the FDI versus export decision of Japanese manufacturers. J Jpn Int Econ 17:448–467

Helpman H (2006a) International organization of production and distribution, NBER Reporter: Research Summary, summer

Helpman H (2006b) Trade, FDI and the organization of firms. J Econ Lit 44:589–630

Helpman H, Melitz MJ, Yeaple SR (2004) Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. Am Econ Rev 94:300–316

Kasahara H, Rodrigue J (2008) Does the use of imported intermediates increase productivity? Plant-level evidence. J Dev Econ 87:106–118

Kohler W, Smolka M (2009) Global sourcing: evidence from Spanish firm-level data. Unpublished paper

Kurz CJ (2006) Outstanding outsourcers: a firm- and plant-level analysis of production sharing. Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Federal Reserve Board, no. 4

Levinsohn J, Petrin A (2003) Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Rev Econ Stud 70:317–341

Melitz M (2003) The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica 71(6):1695–1725

Muuls M, Pisu M (2009) Imports and exports at the level of the firm: evidence from Belgium. World Econ 32(5):692–734

Nunn N, Trefler D (2008) The boundaries of the multinational firm: an empirical analysis. In: Helpman E, Marin D, Verdier T (eds) The organization of firms in a global economy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Spencer B (2005) International outsourcing and incomplete contracts. Can J Econ 38(4):1107–1135

Tomiura E (2005) Foreign outsourcing and firm-level charachteristics: evidence from Japanese manufacturers. J Jpn Int Econ 19:255–271

Tomiura E (2007) Foreign outsourcing, exporting, and FDI: a productivity comparison at the firm level. J Int Econ 72:113–127

Yeaple SR (2006) Offshoring, foreign direct investment, and the structure of U.S. trade. J Eur Econ Assoc 4(2–3):602–611

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to an anonymous referee, Alfonso Rosolia, Luigi Federico Signorini, Marcel Smolka, Lucia Tajoli, Roberto Tedeschi, Davide Vannoni and participants to the 10th ETSG Conference in Warsaw, the 2nd FIW Research Conference “International Economics” in Vienna, the Centro Studi Luca d’Agliano Conference on “Innovation, Internationalization and Global Labor Markets” in Turin and the INFER Workshop on “Firm and Product Heterogeneity in International Trade” in Brussels for their useful comments. I am also grateful to Alessandra De Michele for editorial assistance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Federico, S. Outsourcing versus integration at home or abroad and firm heterogeneity. Empirica 37, 47–63 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-009-9118-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-009-9118-3