Abstract

This paper examines firms’ decision of integrating production and post-production services to serve foreign markets. The author builds a model in which heterogeneous firms choose different locations to produce output, while employ local or send home managers from headquarters to provide post-production services. The model shows that the equilibrium decision of a firm depends on its own productivity level and the mobility of transferring home managers across borders. Using Korean firm- and affiliate-level data, empirical results show that firms choose production locations based on their productivity levels and transport costs, while firms’ choice of service managers depend on informal trade barriers across borders. These findings are consistent with the theoretical implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Firms go through different stages of activity to serve the market. For instance, firms produce intermediate inputs and assembly for final products. After production, firms maximize the value of final products by providing post-production services that include distribution of sales, marketing, and maintenance and repair services. When firms extend to serve foreign markets, they now face a rich array of choices on business activities. To produce final products, for instance, firms may perform different stages of production by themselves in different locations or outsource some of production process to other suppliers. Regarding post-production services, firms may choose to provide services by themselves through establishing service facilities abroad or make a contract with local providers.

Studying for firms’ various activities to serve foreign markets, prior trade literatures have focused on analyzing firms’ production location decisions and their determinants. Examining the effects of cross-border characteristics, traditional trade studies found that firms are likely to serve foreign markets by producing abroad via foreign direct investment (FDI) than exports in countries that incur large transport costs of shipping products from home or in countries that have large market sizes (Brainard 1993, 1997; Horstmann and Markusen 1992; Krugman 1983). On the other hand, recent trade studies began to analyze firms’ production location decisions stemming from the firm heterogeneity. In particular, examining the effects of firm productivity on firms’ foreign entry decisions, Helpman et al. (2004) showed that firms that are more productive than certain cut-off productivity level are profitable to serve foreign markets, where the most productive firms produce abroad via FDI, followed by firms that produce and export from home. Taking into account of multiple stages of production, Grossman et al. (2006) analyzed how firm productivity affects firms’ choice of different organizational forms to integrate producing intermediate goods and conducting final assembly operations in different locations. Developing three-country model that consists of two identical developed countries and a developing country, they showed that firms’ production location decisions to perform different stages of production depend on their productivity levels and the cost of shipping intermediate and final products across borders.

More recently, trade studies began to incorporate post-production services into firms’ entry decisions for serving foreign markets. In particular, a number of theoretical works have considered distribution of sales as post-production services and analyzed the determinants of firms’ choice of foreign market access. For instance, Ishikawa et al. (2010) studied the effects of trade and service liberalizations between countries on firms’ choice of providing services by themselves via FDI or by outsourcing. They showed that by reducing the tariff and the fixed cost of service FDI, the liberalization of both trade in goods and service FDI has positive effects on firms’ choice of FDI for providing services. Studying for firms’ incentives to form cross-border strategic alliances or engage in cross-border mergers, on the other hand, Qiu (2010) considered distribution cost as a main determinant of firms’ entry choices to provide services in foreign markets. In his two-country, multi-firm framework, when firms export products from home, they have a large incentive to form cross-border alliances or engage in cross-border mergers if distribution cost is high. Alternatively, when firms produce abroad via FDI, the choice between cross-border alliances and mergers additionally depends on the plant setup cost such that cross-border merger is likely to be chosen if distribution cost and plant setup cost are high.

In contrast to studying one aspect of firms’ business activities, this paper analyzes how firms choose optimal strategies to integrate production and post-production services for serving foreign markets. I modify Helpman et al. (2004) framework by including two main features. First, firms can produce final products in different locations. If firms produce and export from home, they incur transport costs of shipping products, while firms must bear plant setup costs when producing abroad via FDI. Second, firms provide post-production services by establishing their own facilities in the destination market. In the facilities, firms can provide services either by employing local or transferring home service managers from headquarters where transferring home service managers abroad involves inefficiency due to the informal trade barriers between countries. Using Korean firm- and affiliate-level data, I empirically investigate the determinants of firms’ production location and service decisions.

This paper makes two main contributions to the trade and FDI literatures. First, by incorporating post-production services into the heterogeneous firms trade model, this paper further discusses firms’ decision of providing services after locating production for serving foreign markets. While previous studies that use heterogeneous firms trade model were limited to focus on firms’ choice of production locations (Aw and Lee 2008; Helpman et al. 2004), this paper provides a simple theoretical framework that captures different stages of business activity in which firms practically undertake to serve foreign markets. By allowing heterogeneous firms to choose optimal production locations and different types of service managers, this paper shows that firms’ decision to serve foreign markets not only depends on their own productivity level, but also on country-specific characteristics.

Second, this paper provides an in-depth empirical analysis on firms’ choice of production locations and service managers studied from the theoretical model by using a rich set of affiliate-level data. This unique and unpublished benchmark dataset for Korean multinational firms link 4429 foreign affiliates that operate business worldwide with 2394 parent firms in 2011. While previous empirical studies that use firm-level dataset were limited to use aggregate FDI sales and export sales to analyze firms’ production location choices between home and abroad, this dataset provides quite detailed information on individual foreign affiliates. Critical for the analysis, it contains information on affiliates’ locations, sales and purchases made from different locations, and employment numbers divided by worker’s nationality and occupation. Using such information, this paper empirically analyzes how firms actually choose production locations and different types of service managers in regards to firm- and country-specific characteristics.

In the model, I study the case in which firms with different productivity levels make a decision on locating production and employing service managers to serve different foreign markets: high- and low-income countries, respective to the home country. Countries are different in factor prices and managerial efficiencies such that high-income countries have the most efficient managers but incur the largest cost of production, while low-income countries have the least efficient managers yet incur the smallest cost of production relative to home. The model shows that when serving high-income countries, firms’ production location choices are determined by their productivity levels and transport costs where more productive firms produce abroad by establishing production facilities in countries that incur high transport costs from home. Firms’ service managerial choices, on the other hand, are affected by the managerial efficiency where all firms find it profitable to employ local service managers than transfer home service managers from headquarters. When serving low-income countries, the model shows that firms choose production locations on the basis of their productivity levels where more productive firms produce abroad via FDI, while less productive firms produce and export from home. In contrast to high-income countries, firms’ service managerial choices are determined by the managerial efficiency and inefficiency involved in transferring home service managers across borders. For instance, firms find it profitable to employ local service managers in countries where people are lowly mobile, while they send home service managers to countries where people are highly mobile for transferring home service managers from headquarters.

I then estimate the model by using a sample of Korean firms that operate business abroad through FDI in 2011. Using information on the composition of production workers and service managers inside each foreign affiliate, I construct binary variables that represent firms’ choice of specific production locations with certain types of service managers and specify binary choice models to link firms’ choices with firm productivity and country-specific characteristics. The empirical findings are consistent with the theoretical implications. Inside high-income countries, for instance, firms with different productivity levels choose production locations conditional on the transport costs. Inside low-income countries, on the other hand, the results show that firms choose production locations on the basis of their own productivity level, while employ different types of service managers depending on the cultural distance between Korea and host countries and ethnic Korean population in host countries, which all represent country’s informal trade barriers that involve inefficiency of transferring Korean service managers from parent firms.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 develops a model that analyzes firms’ choice of production locations and different types of service managers for serving foreign markets. Section 3 illustrates Korean firm- and affiliate-level data and describes the variables for the empirical specification. Section 4 contains the empirical strategies and results. Section 5 concludes and proposes future work.

2 Theoretical framework

In this section, I modify Helpman et al. (2004) in which heterogeneous firms choose different locations to produce differentiated varieties and employ different types of service managers to provide post-production services of products. To examine firms’ decision for serving different types of foreign markets, I divide the analysis into two scenarios when firms serve high-income (North) and low-income countries (South), respective to home.

Consumers in all countries have following Dixit–Stiglitz preference over differentiated goods

where n is mass of varieties available to consumers, indexed by \(\omega\); \(x(\omega )\) is consumption of variety; and \(q(\omega )\) is service quality of variety \(\omega\), as perceived by the consumer; and \(\rho\) is a measure of substitutability. Hence, each variety is a Cobb–Douglas bundle of physical quantity and perceived service quality.Footnote 1 Consumers maximize utility function subject to budget constraints

where y is the exogenously given per capita income. Solving consumer’s maximization problem yields the following demand for variety \(\omega\)

where \(\sigma = 1/1-\rho > 1\) is the elasticity of substitution between varieties; \(R = Ny\) is a national income with N as exogenously given population of a country; and P is the ideal price index of the country.Footnote 2 To capture the role of service managers, I assume that consumer’s perceived service quality takes the following form

where \(\lambda \in (1, \infty )\) is the true service quality of variety and \(\alpha (z)\) is a function of exogenous expertise level (z) of service managers.Footnote 3 This form therefore indicates that consumer’s perceived service quality is affected by the true service quality of the product and the manager’s efficiency to produce better service quality for the product.Footnote 4

On the production side, a continuum of firms exists in the home country that differs in their productivity levels indexed by \(\theta\). A firm uses only labor to produce variety \(\omega\). Firm technology is represented by the constant marginal cost of production, which is assumed to be mobile internationally and can be replicated by its local subsidiary. The unit variable cost of firms with productivity level \(\theta\) that serves foreign markets by producing in country k is denoted by \(C_{k}\):

where \(w_{k}\) is the wage level of production workers in country k and \(t \ge 1\) is the melting-iceberg transport cost of shipping products.Footnote 5 Each country differs in factor prices such that I assume the wage level of workers to be the highest in the North (n), followed by Home (h), and the South (s) has the lowest: \(w_{n}> w_{h} > w_{s}\). In addition to the variable costs, firms that enter a foreign country via FDI incur the fixed plant setup cost.

To produce final outputs, firms can either produce at home and export or establish production facilities in the host country. Export incurs the transport cost of shipping products \((t > 1)\), but saves the fixed plant setup cost, while FDI would impose the fixed cost of establishing a production facility (f), but conserve the transport cost of shipping products from home \((t=1)\).Footnote 6 If cost differences across countries are the main determinant of firms’ production location decisions, proximity to consumer is a crucial element for firms needing to provide post-production services. To provide services of post-production outputs, therefore, all firms must establish service facilities in the destination market which incur the fixed plant setup cost (g). Firms then employ local managers or transfer home managers from headquarters, whose decision depends on the managerial efficiency to provide services. Following the idea from Nocke and Yeaple (2007), service managerial efficiency takes the following form

where \(\delta \in (0,1)\) is the degree of international mobility of home service managers, representing country’s informal trade barriers that hinder the efficiency of service managers to provide services abroad.Footnote 7 In regards to the managerial expertise, I assume that the North has the highest, followed by home, and the South has the lowest such that \(z_{n}> z_{h}> z_{s} > 1\).Footnote 8

Within an industry, profit of a firm i that serves foreign country is as follows

where \(F_{j}\) is the fixed entry costs of setting up facilities abroad, denoted by subscript \(j=f,g\) (f, for production facility; g, for service facility) and \(\omega (z)\) is the return to skills of a service manager endowed with expertise level z.Footnote 9 Solving for the firm’s profit maximization problem, the optimal price is a constant mark-up \((\sigma /\sigma -1 = 1/\rho )\) over marginal cost:

Using country’s demand level and optimal price, the profit of firm i producing variety to serve a foreign country can be written as a function of firm productivity level and service quality

where \(B = (1-\rho )R/(\rho P)^{1-\sigma }\). If firm i produces in the foreign country, for instance country k via FDI, then \(\overline{w} = w_{k}\). If firm i produces in the home country and export, then \(\overline{w} = w_{h}t\).

After production, each firm provides post-production services. For providing services, I assume that firms choose the level of service quality of products to maximize the profit in which higher service quality of products requires higher fixed costs. This captures well-established idea that improving the level of service quality requires additional activities such as establishing additional service centers, purchasing machinery equipments, marketing, and advertisement activities which are mainly fixed costs in nature. For expositional simplicity, I follow Crinò and Epifani (2009) by assuming that improving the service quality of products (\(\lambda\)) requires a fixed cost equal to \({\frac{1}{\eta }}\lambda ^{\eta }\), where \(\eta > 0\) is the elasticity of the fixed cost to service quality of the product.Footnote 10 Firms therefore solve the following problem:

Solving this problem yields optimal service quality, \(\lambda ^{*}\):

where \(\eta > 1\) by the second-order condition for a maximum. Optimal service quality of the product implies that, holding other factors constant, more productive firms improve the service quality of products by paying the additional fixed costs. Using optimal service quality \((\lambda ^{*})\) into firm’s profit yields:

Profit function suggests that for serving foreign markets, firms have four strategies from which to choose. Firms can produce and provide post-production services in the host country with either home or local service managers, implying that firms integrate all of business activities in the host country by establishing production and service facilities. This integration strategy would impose the highest fixed costs of establishing facilities \((f+g)\) and the cost of managing different types of service managers, but conserve the transport costs. Alternatively, firms can produce at home and provide post-production services in the host country with either home or local service managers, indicating that firms produce in the home country and export products to the service facilities in the destination market. This strategy imposes the fixed cost of setting up a service facility (g) and the cost of managing different types of service managers, and the transport costs.

In the following, I examine different strategies that firms can choose to serve high- and low-income countries, respective to home.

2.1 Firms serving high-income countries

When firms enter the North, the profit functions of four strategies are as follows:

Equations (13) and (14) represent firm’s profit from establishing production and service facilities in the North with home service managers and with local service managers, respectively. Equations (15) and (16) represent firm’s profit from establishing a service facility in the North with home service managers and with local service managers, respectively.Footnote 11

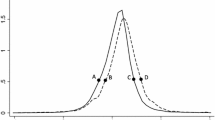

Comparing for the profits attainable for firms with different productivity levels, given that \(z_{n} > z_{h}\) and \(\delta \in (0,1)\), the profit from providing services through local service managers dominates the profit from transferring home service managers under the same production locations. Between two possible production location choices: home and host countries \((\Pi ^{HL}, \Pi ^{SL})\), which production location to choose depends not only on the firm productivity level, but also on the relative magnitudes of transport costs, fixed costs and relative wage. In particular, as long as transport cost is larger than the wage differentials between the North and Home, such that \(t > w_{n}/w_{h}\), producing in the North is more profitable than producing at home at every productivity level in the absence of fixed costs. Conditional on the fixed plant setup costs, it follows that

and

Therefore, there exist (unique) thresholds \(\theta ^{1}\) and \(\theta ^{2}\) such that firms with productivity \(\theta \in (0,\theta ^{1})\) do not enter the foreign market; firms with productivity \(\theta \in (\theta ^{1}, \theta ^{2})\) produce at home and export to service facilities abroad and provide services with local service managers; and firms with productivity \(\theta > \theta ^{2}\) produce in the host country and provide services with local service managers.Footnote 12

On the other hand, as long as transport cost is smaller than the wage differentials between the North and Home, such that \(t \in (1, w_{n}/w_{h})\), producing at home is more profitable than producing in the North at every productivity level. In particular, it follows that

and

In this case, a unique threshold \(\theta ^{3}\) exists such that firms with productivity \(\theta \in (0,\theta ^{3})\) do not enter the foreign market, whereas firms with productivity \(\theta > \theta ^{3}\) produce at home and export to service facilities abroad and provide services with local service managers. In other words, when serving countries that incur high production costs, yet relatively small transport costs, firms are better off to produce and export from home than produce abroad via FDI. In contrast to prior trade literature that analyze FDI flows between Northern countries or from North to South, this model shows that if FDI flows from South to North, firms’ production location choices are affected by the transport costs of shipping products from home.

2.2 Firms serving low-income countries

When firms enter the South, the profit functions of four strategies are as follows:

Consistent with the previous subsection, Eqs. (21) and (22) indicate firm’s profit from establishing production and service facilities in the South and providing services with home service managers and with local service managers, respectively. Equations (23) and (24) indicate firm’s profit from establishing a service facility in the South and providing services with home service managers and with local service managers, respectively.Footnote 13

In contrast to serving high-income countries, firms now have to make a decision on providing services with different types of managers. Depending on the degree of international mobility, it is clear that as long as the mobility is higher than the managerial expertise differentials between the South and Home, such that \(\delta \in (z_{s}/z_{h},1)\), firms find it more profitable to transfer home service managers from headquarters than employ local service managers under the same production locations. Alternatively, as long as the mobility is lower than the managerial expertise differentials between the South and Home, such that \(\delta \in (0, z_{s}/z_{h})\), the profit from providing services through local service managers dominates the profit from transferring home service managers from headquarters under the same production locations.

In regards to the production location choice, given that \(w_{h} > w_{s}\) and \(t > 1\), firms are better off to produce in the South than Home at every productivity level in the absence of fixed costs. Conditional on the fixed plant setup costs, it is straightforward to find that the most productive firms bear high fixed costs of establishing production and service facilities in the South and produce varieties with low production costs, whereas less productive firms produce at home and export to their service facilities in the South.

When firms serve low-income countries, the model shows that firms choose production locations on the basis of their productivity levels, such that more productive firms produce in the host country, while less productive firms export from home. For providing post-production services, firms’ service managerial choices depend on the degree to which home service managers are mobile between countries where firms are better off to employ local service managers in low-mobility countries, while transfer home service managers from headquarters to high-mobility countries. The sorting of strategies by firms’ productivity levels and country-specific characteristics provides the building block for the empirical specification presented in next sections.

3 Data

3.1 Data analysis

To test theoretical implications on firms’ choice of production locations with different types of service managers, this paper requires dataset that captures cross-border activities of firms at the affiliate level, specifically showing how firms serve foreign markets either by producing in the host country or by exporting products to their service affiliates, and how firms provide services through different types of service managers inside their affiliates. For the empirical analysis, this paper uses one of the few dataset that directly observes cross-border activities of firm at the micro level. Here, I use data on Korean FDI obtained from the Overseas Direct Investment Statistics from the Export–Import Bank of Korea.Footnote 14 This affiliate-level cross-sectional dataset includes the full list of Korean worldwide investment in 2011 where 4429 foreign affiliates are linked with 2394 parent firms that hold at least 10 % ownership.

Critical for the analysis, the dataset includes quite detailed information on affiliate’s location, sales and purchases, and the composition of employment.Footnote 15 For instance, the affiliate reports its sales and purchases divided by: (1) sales and purchases made from other affiliates sharing the same parent in the host country, (2) sales and purchases made from other unaffiliated agents in the host country, (3) sales and purchases made from the parent in Korea, (4) sales and purchases made from other unaffiliated agents in Korea, (5) sales and purchases made from other affiliates sharing the same parent in third countries, and (6) sales and purchases made from other unaffiliated agents in third countries. Also, the most interesting feature of the dataset is that it provides affiliate’s employment numbers that are divided by the worker’s nationality and occupation. Decomposed into employees from Korea and host country, their occupations are divided into top managers, middle managers, service managers, and production workers.Footnote 16 Using such information on affiliate’s sales and purchases made from different locations, and the composition of employment, I categorize firms’ choice of production locations with different types of service managers studied in the theoretical model. For instance, it is clear to find that affiliates that engage in local sales only with local service managers by making all of purchases from parents in Korea represent firms’ choice of producing and exporting from home to their service facilities abroad and providing services with local service managers in the theoretical model.

With regards to the parent firms, the affiliate-level dataset only provides firm identification number for each affiliate. Therefore, I match affiliates to their parent firms and use firm-level data from other source. Here, I link the affiliate-level dataset from the Export–Import Bank of Korea with a commercial database sold under the name of KISLINE from the NICE Information Services Ltd. This extensive dataset includes all Korean firms that are registered as a corporation and contains detailed information of interest, including balance sheets, profit and loss statements, domestic and export sales, and employment numbers. Each firm is classified by the five-digit Korean Standard Industrial Classification (KSIC), which is similar to commonly used International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) or the North America Industry Classification System (NAICS). Since firm-level dataset does not provide information on local subsidiaries abroad, I merge firm-level data from the KISLINE with affiliate-level data from the Export–Import Bank of Korea for the analysis.

For the empirical specification, I consider firms in five-digit KSIC manufacturing sectors that operate business abroad through their own affiliates. In particular, since firms in the theoretical model employ service managers in their foreign facilities to serve local markets, I include firms whose affiliates only make local sales in their location by employing service managers.Footnote 17 Using these affiliates, I construct four binary variables that represent firms’ choice of production locations with different types of service managers by observing the presence of production workers and the certain type of service managers inside the affiliate. First, manulocal is a binary variable equal to 1 if the affiliate includes production workers and local service managers, capturing firms’ choice of producing in the host country and employing local service managers. Second, servicelocal is a binary variable equal to 1 if the affiliate only includes local service managers and no production workers, capturing firms’ choice of producing and exporting from home and employing local service managers. Third, manuhome is a binary variable equal to 1 if the affiliate includes production workers and Korean service managers, capturing firms’ choice of producing in the host country and transferring home service managers from headquarters. Finally, servicehome is a binary variable equal to 1 if the affiliate only includes Korean service managers and no production workers, capturing firms’ choice of producing and exporting from home and transferring home service managers from headquarters.

The key explanatory variables used to analyze firms’ production location choices are firm productivity level and transport cost. To measure firm productivity, I use labor productivity (productivity).Footnote 18 As a measure of transport cost, I calculate a tariff rate by using data from UNCTAD-TRAINS and WITS (tariff). These data include information on tariff rates and trade data using the six-digit HS codes for 103 countries. Here, I compute unweighted averages using the five-digit ISIC level and map these figures into the five-digit KSIC industry level by using Trade Statistics provided by the Korea International Trade Association.Footnote 19

The key explanatory variable also includes the degree to which home service managers are mobile from home to the host country. In the model, the degree of mobility indicates country’s informal trade barriers that hinder the efficiency of home managers to provide post-production services in the foreign market. To capture informal trade barriers, I follow Kogut and Singh (1988) and Debaere et al. (2013) by using Hofstede (1980) seminal indices on culture distance between home and host countries (cultural distance), which is a composite index on the deviation between home and host countries along the four cultural dimensions; in particular, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity/femininity, and individualism.Footnote 20 For the robustness check, suggested by Rauch and Trindade (2002), I also use ethnic Korean population share (popshare) in the host country to capture coethnic Korean networks. Emphasized by Rauch and Casella (2003), coethnic networks are important business and social networks that can overcome informal trade barriers in international trade. For instance, it helps firms to facilitate distribution of products in the market or supply matching and referral services. Therefore, I expect host countries to be highly mobile of transferring Korean service managers as they have a small cultural distance from Korea or have a large ethnic Korean population.

To capture other firm characteristics that affect firms’ decisions, I add firm-specific assets. First, I use firm’s R&D intensity, computed as firm’s total R&D expenditures divided by total sales. Second, I use firm’s international experience, which is measured by the number of previous affiliates a firm had worldwide (experience), and the total employment (size). Broad international experience increases previous knowledge of local markets, connection to bureaucracy, and business culture which all facilitate multinational firms to invest abroad (Tekin-Koru 2012). Therefore, this previous knowledge may influence firm’s decision not only on production locations, but also on providing services. I expect positive signs on all of choices, even though the strength of this effect is ambiguous. Furthermore, using information on the establishment date of each affiliate, I construct a binary variable, newFDI, which is equal to 1 if a firm locates an affiliate abroad in 2011. It represents new firm entry to foreign markets and allows me to study the decision of new FDI firms.

For other country-specific characteristics, I include country’s market size and income level by using real GDP (GDP) and real GDP per capita (GDP per capita), respectively, and state of infrastructure by constructing an index using data on telephone, computer and internet usage (infra).Footnote 21 As a proxy for the managerial expertise level, I use the percentage of 20–29 year olds with a tertiary education (ISCED 5 and 6) in mathematics, sciences or technologies (education).Footnote 22 Finally, concerning the fact that firms’ strategic functions such as performing service activities could be highly sensitive to the legal environments (Defever 2006), I use an indicator of the quality of policy formulation and the credibility of the government’s commitments to such policies (gov’t effectiveness), which ranges from −2.5 to 2.5 where a higher number indicates more political stability. All of country-level data are obtained from the World Development Indicators and World Governance Indicators from the World Bank, and LABORSTA from the International Labour Organization. Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics of variables used for the empirical specifications.

Binary dependent variables that represent firms’ choices in Table 1 show that among Korean FDI firms whose foreign affiliates engage in local sales with service managers, most of firms appear to produce goods in the host country by investing in production affiliates that include production workers and provide services by employing local service managers, followed by firms that invest in service affiliates that do not include production workers and provide services by employing local service managers.Footnote 23 In regards to firms that invest in service affiliates from the table, they represent firms’ choice of producing at home and exporting to their service facilities abroad in the theoretical model. To evaluate whether these firms actually export goods to their service affiliates abroad, I use information on affiliate’s purchases made from different locations to compute for its share of purchases from the parent firm in Korea. Purchase share from HQ in the table is computed as affiliate’s purchases made from the parent firm in Korea divided by its total purchases and indicates intra-firm trade from the parent’s perspective. Purchase share from HQ for firms’ choices in the table shows that the average service affiliate imports more than 95 % of products from the parent firm in Korea, while the average production affiliate imports less than 15 % of products from the parent. This provides evidence that Korean FDI firms that invest in service affiliates to serve local markets actually export goods to their affiliates and represent firms’ choice of producing and exporting from home to service facilities abroad in the theoretical model. Also, with regards to country’s GDP per capita that is used to distinguish between more or less advanced host countries than Korea, the table shows that the average GDP per capita of less advanced countries is almost 1/5 of that of Korea, while the average GDP per capita of more advanced countries is almost a double than that of Korea. All of these statistics suggest that using Korean FDI firm data is appropriate to compare firms’ choice of production locations with different types of service managers for serving between high- and low-income countries in the theoretical model.

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Empirical strategy

Using binary choices as dependent variables, I use probit model to estimate the effects of firm- and country-specific characteristics on the likelihood of firms choosing specific production locations with certain type of service managers. A firm’s profit function for each choice is specified as

where \(\Phi (\cdot )\) is the standard normal cumulative distribution function, assuming that error terms are independent and normally distributed, and \(k = \{{manulocal, servicelocal, manuhome, servicehome }\}\) is firm’s choice of specific production locations with certain type of service managers. In particular, \(\Pi _{ijmanulocal}\) denotes firm i’s profit from country j by choosing to produce in the host country and employ local service managers, \(\Pi _{ijservicelocal}\) stands for firms that choose to produce and export from home to their service affiliates and employ local service managers, \(\Pi _{ijmanuhome}\) represents firm profit from choosing to produce in the host country and send home service managers from headquarters, and \(\Pi _{ijservicehome}\) represents firm profit from choosing to produce and export from home and send home service managers to their service affiliates. Vector \({\mathbf{X}}_{\mathrm{i}}\) denotes firm-specific characteristics such as firm productivity, size, and experience. Alternatively, \({\mathbf{Z}}_{\mathrm{j}}\) represents country-specific characteristics that include tariff rates, GDP per capita, cultural distance, ethnic Korean population share, education level, and government effectiveness.

For the robustness check, I also capture the dependency of firms’ choice of specific production locations with certain of service managers on firm- and country-specific characteristics as a simple linear function. Here, I specify linear probability model (LPM), which is simple to estimate and to interpret the effects of firm- and country-specific characteristics on firms’ choices. In particular, I specify

where \(Y_{ijk}\) is a binary outcome variable that represents whether firm i has chosen specific production locations with certain type of service managers (k) in country j, and \(X_{i}\) and \(Z_{j}\) denote firm- and country-specific characteristics respectively.

From these specifications, I expect firm- and country-specific variables to have different effects on firms’ choice of production locations with different types of service managers between high- and low-income countries. For instance, by adding an interaction term between firm productivity and tariff rates in each specification, I expect firm productivity to be positively associated with firms’ choice of producing abroad with either type of service managers as firms invest in high-income countries that impose high tariff rates on products shipped from Korea. For firms that invest in low-income countries, on the other hand, I expect cultural distance to have positive effects, while ethnic Korean population share to have negative effects on firms’ choice of employing local service managers within either type of affiliates.

4.2 Empirical results

Table 2 reports the results from estimating the effects of firm- and country-specific characteristics on the likelihood of firms’ choosing production locations with different types of service managers by using probit model. Five-digit KSIC industry sector dummies are included to control for industry-specific fixed effects and robust standard errors clustering for host countries are reported in the parentheses to account for the possible correlated shocks that might affect all foreign affiliates in the same host country. To make it consistent with the theoretical implications on firms’ choices for serving between high- and low-income countries, I divide sample of firms into more and less advanced host countries than Korea based on country’s real GDP per capita relative to that of Korea.

Using sample of firms that invest in and serve high-income countries, coefficient estimates on productivity and tariff in columns (1) through (4) show that firms are more likely to produce abroad and employ either type of service managers in countries that impose high tariff rates on products shipped from Korea or as firms are more productive. Alternatively, firms tend to produce at home and export to their service affiliates and employ either type of service managers in countries that impose small tariff rates or as firms are less productive. In particular, coefficients on the interaction term between productivity and tariff in columns (1) and (3) are positive and significant, implying that more productive firms are more likely to produce and provide services with either type of service managers in countries that incur large transport costs from Korea. On the other hand, coefficient estimates on cultural distance are positive and significant in columns (1) and (2), implying that firms are likely to employ local service managers within either type of affiliates in countries where culturally distant from Korea. However, firms’ choice of transferring Korean service managers appear to be irrelevant to cultural distance between home and host countries.

Examining firms that invest in and serve low-income countries, probit estimates of productivity in columns (5) through (8) show that firm productivity is positively associated with firms’ choice of investing in production affiliates and employing either type of service managers, while negatively associated with firms’ choice of investing in service affiliates and employing either type of service managers. These results imply that more productive firms are more likely to produce in the host country and employ either type of service managers, while less productive firms prefer to produce at home and export to service facilities abroad and employ either type of service managers for serving low-income countries. In contrast to firms that invest in high-income countries, however, coefficients on tariff and its interaction term with productivity are insignificant, implying that firms’ production location choices for serving low-income countries are mainly determined by their own productivity level.

Coefficient estimates on cultural distance in columns (5) through (8) are all significant and have different signs. Their signs imply that firms are more likely to employ local service managers within either type of affiliates in countries that are culturally distant from Korea, while transfer Korean service managers to either type of affiliates located in countries that share cultural similarities with Korea. Consistent with the theoretical implications, these results suggest that firms’ choice of service managers are significantly determined by country’s informal trade barriers. Also, coefficient estimates on education in columns (7) and (8) are significant, implying that country’s education level is critical for firms’ choice of transferring Korean service managers to either type of affiliates. Their signs indicate that firms favor transferring Korean service managers to countries with low education level, which is different from the results in high-income countries.

Turning to other covariates, it appears that firms’ production location and service decisions are affected by different variables between high- and low-income countries. For instance, coefficients on infra and GDP per capita in columns (1) through (8) show that country’s state of infrastructure affects firms’ choice of production locations for serving high-income countries, while country’s GDP per capita appears to have an influence on firms’ choice of service managers in low-income countries. Across high-income countries, coefficients indicate that firms are likely to produce abroad through production affiliates with either type of service managers in countries with poor infrastructure services. Across low-income countries, on the other hand, firms tend to employ local service managers within either type of affiliates in countries with high GDP per capita. Also, coefficients on gov’t effectiveness in columns (5) and (6) are positive and significant, implying that firms are more likely to employ local service managers within either type of affiliates in countries where politically stable. These results suggest that firms’ decision about employing different types of service managers are affected by country’s political and social factors in addition to the informal trade barriers when serving low-income countries.

For the robustness check, Table 3 reports the estimation results from using linear probability model, which is simple to estimate and to interpret the effects of firm- and country-specific characteristics on firms’ choice of production locations with different types of service managers. The estimates and significance of coefficients are approximately same as probit coefficients reported in Table 2. Inside high-income countries, for instance, the results show that firm productivity and tariff rates independently and jointly affect firms’ choice of production locations, regardless of service manager type. Coefficients on interaction term between productivity and tariff also imply that more productive firms are more likely to produce and employ either type of service managers in countries that incur large transport costs from Korea. Inside low-income countries, firms appear to choose production locations, regardless of service manager type, on the basis of their own productivity level such that more productive firms produce in the host country, while less productive firms produce at home and export products to their service affiliates abroad.

Examining the effects of cultural distance on firms’ decision for serving high-income countries, coefficient estimates in columns (1) and (2) are positive and significant, implying that firms’ choice of employing local service managers within either type of affiliates are positively associated with the cultural distance from Korea. Same coefficient estimates in columns (5) through (8), on the other hand, are all significant and have different signs. Their signs indicate that in low-income countries, firms have a propensity to employ local service managers within either type of affiliates in countries where culturally distant from Korea, while transfer home service managers to either type of affiliates in countries that share cultural similarities with Korea. For other control variables, coefficient estimates on education and gov’t effectiveness in columns (5) through (8) also suggest that firms’ choice of service managers for serving low-income countries depend on country’s education level and political stability. Their signs indicate that firms tend to employ local service managers within either type of affiliates in countries where politically stable, while send home service managers to either type of affiliates in countries with low eduction level.

Since labor productivity and cultural distance between home and host countries are used and shown as main determinants of firms’ choice of production locations with different types of service managers, I use alternative measures for the robustness check. Here, I use an approximate total factor productivity (ATFP) and ethnic Korean population share in the host country as alternative measures for firm productivity and country’s informal trade barriers. In particular, while TFP is widely used in economic literatures as an ideal measure for representing firm productivity, using cross-sectional data with limited information on production inputs, such as capital stocks and material inputs, make it impossible to estimate the true TFP for each firm in the sample. Therefore, I use ATFP only for a robustness check purpose.Footnote 24 Probit estimates from using alternative measures are presented in Table 4.Footnote 25

Examining firms that serve high-income countries, probit estimates in columns (1) and (3) show that firms’ choice of investing in production affiliates abroad and employing either type of service managers are significantly determined by their productivity levels and tariff rates. Coefficients on interaction term between ATFP and tariff also support previous results that more productive firms are more likely to produce and provide services with either type of service managers in countries that incur large transport costs from home. In contrast to the previous probit estimates, however, ATFP does not appear to have significant effects on firms’ choice of investing in service affiliates abroad and employing either type of service managers. On the other hand, coefficient estimates on popshare in columns (1) and (2) are negative and significant, indicating that firms tend to employ local service managers within either type of affiliates in countries where small Korean population are present. Along with the previous estimates on cultural distance between home and host countries, these results suggest that firms’ choice of employing local service managers in high-income countries are determined by country’s informal trade barriers.

Inside low-income countries, probit estimates of ATFP in columns (5) through (8) show that firms’ production location choices, regardless of service manager type, are significantly determined by their productivity levels. Their signs suggest that more productive firms produce abroad and employ either type of service managers, while less productive firms produce at home and export to service affiliates abroad and employ either type of service managers. Also, firms’ service managerial choices appear to be significantly associated with ethnic Korean population share. Coefficients on popshare in columns (5) through (8) show that firms are likely to employ local service managers within either type of affiliates in countries where small Korean population are present, while firms tend to transfer Korean service managers to either type of affiliates in countries where large Korean population are present. These results from using alternative measures for firm productivity and country’s informal trade barriers are consistent with the previous results and support the theoretical implications on firms’ decision of choosing production locations with different types of service managers with regards to firm- and country-specific characteristics for serving between high- and low-income countries.

In the previous specifications, I used information on the presence of production workers and the composition of service managers inside the affiliates to represent firms’ choice of specific production locations with certain type of service managers. Therefore, previous dependent variables include firms’ decision of choosing production locations and service managers for serving foreign markets. To test whether firms’ production location and service managerial choices are interrelated, I construct binary variables that each represents firms’ choice of production locations and service managers. For the robustness check, I then specify bivariate probit model to test for the possible interrelationship between these two choices and identify the determinants of each choice.Footnote 26

To capture firms’ decision of producing in the host country, I construct a binary variable, production, which is equal to 1 if the affiliate includes production workers and zero if the affiliate does not include production workers, capturing firms’ decision of producing and exporting from home to service affiliates abroad. To represent firms’ choice of employing local service managers, I construct a binary variable, local managers, which is equal to 1 if the affiliate includes local service managers and zero if it includes Korean service managers, capturing firms’ choice of transferring home service managers from headquarters.

Table 5 reports the results from estimating bivariate probit model. Consistent with the previous specifications, five-digit KSIC industry sector dummies are included and robust standard errors clustering for host countries are reported in the parentheses. The correlation coefficients (\(\rho\)) from using sample of firms that invest in high- and low-income countries are negative yet insignificant to reject that \(\rho = 0\), implying that a complementary relationship does not exist between firms’ decision to produce in the host country and to provide services by employing local service managers.

Examining the determinants of firms’ production location choices, coefficient estimates in the first column show that firm productivity and tariff rates are positively and significantly associated with firms’ decision to produce in the host country for serving high-income countries. The interaction term between productivity and tariff is also positive and significant, implying that more productive firms are more likely to produce in high-income countries that incur large transport costs from home. Alternatively, coefficient estimates in the third column show that firms’ production location choices for serving low-income countries are significantly associated with their own productivity level where more productive firms tend to produce abroad than to produce at home. In contrast to firms that invest in high-income countries, country’s tariff rate appears to have insignificant effects on firms’ production location choices independently and jointly with firm productivity in low-income countries.

To better understand how marginal effects of firm productivity level on the probability of producing in the host country interact with country’s tariff rate, I follow Ai and Norton (2003) and Greene (2010) by estimating univariate probit model and computing the average marginal effect of firm productivity on the success probability of producing in the host country based on different tariff rate levels, which are presented in Table 7 in the “Appendix”. The first column of Table 7 show that the marginal effect of firm productivity corresponds to upward direction in tariff rates. Basically, this implies that firm productivity level becomes more effective in enhancing the probability that a firm will choose to produce in high-income countries where tariff rates are higher. In other words, more productive firms are more likely to invest in production affiliates in countries that incur large transport costs from home. The marginal effect gains statistical significance at the 5 % level in all ranges of the tariff rates, implying that the positive effect is realized in all countries with different levels of tariff rates. Using sample of firms that serve low-income countries, on the other hand, coefficient estimates in the second column show that the magnitude of the marginal effect of firm productivity gradually decreases as the tariff rate increases. However, it does not hold the statistical significance in all ranges of the tariff rates, implying that firm productivity and tariff rates do not have significant interaction effects on firms’ production location choices in low-income countries.

Investigating firms’ service managerial choices, coefficients on cultural distance in columns (2) and (4) of Table 5 are positive and significant. It implies that firms are more likely to employ local service managers than transfer Korean service managers in high- or low-income countries that have large cultural distance from Korea. Also, consistent with the previous results, bivariate probit estimates in the fourth column show that country’s education level and political stability have significant impact on firms’ service managerial choices in which firms tend to employ local service managers than transfer home service managers in low-income countries with high education level or where politically stable.Footnote 27 All of these bivariate probit estimates support previous probit and LPM results that firms’ production location choices are associated with economic factors such as firm productivity and transport costs, while their service managerial choices are determined by country’s informal trade barriers and social factors such as country’s education level.

5 Conclusion and future work

In this paper, I study firm’s integration decision that involves producing final outputs and providing post-production services to serve foreign markets. In the theoretical model, consumers in all countries perceive the service quality of products based on the inner service value of products and the efficiency of service managers who are endowed with country-specific expertise level to demonstrate the service value of products. In order to provide post-production services, therefore, firms must establish their own facilities in the final consumption market and employ either local or home service managers, while they can produce outputs either in their home or host countries. Examining two scenarios when firms enter countries with higher- or lower-income levels relative to home, the model shows that the equilibrium decision of a firm on choosing production locations and different types of service managers depends on its own productivity level and country-specific characteristics.

By adding service quality differences into the heterogeneous firms trade model, this paper further discusses how heterogeneous firms provide post-production services after choosing optimal production locations for serving foreign markets. While previous studies that use heterogeneous firms trade model to examine firm’s decision to serve foreign markets were limited to study its production location choices, this paper provides a simple theoretical framework that captures different stages of business activity in which firms practically undertake to serve foreign markets. As a result, I introduce that a new pattern of FDI, a firm activity of investing in service facilities abroad to serve local markets with products imported from headquarters, appears as one of optimal strategies that firms can choose to serve foreign markets. To my knowledge, this has not been studied before.

Using affiliate- and firm-level data for Korean multinational firms in 2011, I empirically analyze firms’ decisions by constructing binary variables that represent firms’ choice of specific production locations with certain type of service managers. Using binary choice models, I obtain the estimation results consistent with the theoretical implications that firms’ production location choices are affected by their own productivity level, while their service managerial choices are determined by country’s informal trade barriers. Between high- and low-income countries, in particular, I find that firms’ choice of producing in high-income countries are jointly determined by firm productivity and transport costs of shipping products from Korea, while their choice of producing in low-income countries are determined by their own productivity level. On the other hand, country’s informal trade barriers measured by the cultural distance between home and host countries and ethnic Korean population share appear to have significant impact on firms’ choice of employing local service managers in high-income countries, while they have significant effects on firms’ choice of employing between local and Korean service managers in low-income countries.

These results provide important policy implications for developing countries by showing that FDI may create jobs not only for production workers, but also for skilled managers. While previous studies that examine firms’ FDI decisions were limited to consider developing countries as a production platform with no demand (Grossman et al. 2006), this study provides a framework where employment for local service managers can be created by considering low-income countries as a final consumption market. In particular, the results that country’s social and political factors, such as education level and political stability, significantly affect firms’ decision of employing service managers in low-income countries imply that government’s investment in social and human capital can increase foreign investment from outsider firms with a purpose of serving local markets and subsequently, create jobs for production as well as service sectors.

The main goal of this paper was to study firm’s integration decision to serve foreign markets by incorporating the decision on providing services after production. As such, a range of questions including other options in the firm’s decision are not addressed in this paper. I have not considered various possibilities to serve foreign markets that are important for a full account of firm strategies, such as outsourcing post-production services to local firms or engaging in cross-border mergers and acquisitions, or possibility of investing in physical product quality. Furthermore, given this paper’s focus on studying firm activities to serve foreign markets with different sizes, the analysis was limited to comparing firms’ choice of strategies to serve between high- and low-income countries relative to the home country.

Furthermore, one of primary interests in the present study is to examine the effects of service managers on firms’ choice of international organization forms. The basic premise of the model, therefore, is that the preference for the service quality of products by a consumer in all countries is affected by the managers’ efficiencies. Put differently, this assumption implies that consumer’s preference is homothetic with respect to per capita income. Indeed, prior trade literature have analyzed the non-homotheticity of demand for physical product quality and found that the relative demand for high-quality products is higher in high-income countries (Hallak 2006). For future research, therefore, it would be interesting to study how the non-homotheticity of demand for service quality affects firms’ decisions to serve global markets. Furthermore, including both service and product qualities in consumers’ preferences would also yield various implications on multinational firm activities. These questions are left for future research.

Notes

The same formulation is found in Manasse and Turrini (2001) who introduce a perceived product quality that depends on the skill of the entrepreneur in the model to show that in the presence of heterogeneity among entrepreneurs producing quality-differentiated goods, trade can spur within-group wage inequality. While I use their idea by adding perceived service quality in consumer’s preference, where consumers discriminate more among products by placing weight on their perceived service quality of the product, which is affected by the skills of service managers, main features are different in this context. For instance, while entrepreneurs in Manasse and Turrini (2001) model have different abilities to produce a single variety of a differentiated good and make a decision on whether to export or stay home, service managers in my model are endowed with country-specific managerial expertise level and employed by firms to demonstrate the service quality of post-production goods.

\(P = \left[ {\int _{0}^{n} q(w)p(w)^{1-\sigma } dw} \right] ^{{\frac{1}{1-\sigma }}}\).

\(\lambda\) implies inner service value of the product, for example, a 10-year service warranty or 24/7 roadside assistance for an automobile. Alternatively, the expertise level of service managers indicates manager’s ability to demonstrate and perform the service value of the product, such as communication skills or marketing expertise related to providing services.

By assuming that the managerial expertise, rather than per capita income, affects consumer’s preference for the service quality of products, I do not address the effects of differences in the income distribution on demands. See Crinò and Epifani (2009) and Fajgelbaum et al. (2011) for the analysis on the effects of product quality on the pattern of trade between countries based on non-homotheticity of preferences.

As in Melitz (2003), the marginal cost is inversely related to firm productivity level and is independent of service quality.

Since my primary interest is to study firms’ decision of serving countries that are richer or poorer relative to the home country by using two-country model, the possibility of firms’ producing outputs in third countries is excluded in this section. In the “Appendix”, however, I discuss for the possibility of firms to produce outputs in the third production location.

Indeed, Maurin et al. (2002) provide evidence that domestic firms are more competitive than foreign firms in marketing activities in their country. By assuming that service managerial efficiency takes the following form, it captures the idea that service managers are more effective in their home country than abroad due to country’s informal trade barriers, such as exotic business environment.

Since service managers demonstrate or perform the inner service value of post-production goods with their endowed expertise level, I assume that the return to skills of a service managers is proportional to the manager’s expertise level (z) by taking the following functional form, \(\omega (z)\) where \(\omega (z) > 0\), \(\omega '(z) > 0\).

Recent studies that analyze product quality as a source of firm heterogeneity assume that product quality is endogenous and requires additional fixed costs for the upgrading (Crinò and Epifani 2009; Hallak and Sivadasan 2009; Johnson 2012). Following their idea of endogenous quality, I assume that each firm improves the true service quality of the product after production by choosing the optimal level of service quality which requires the fixed costs for the upgrading. These fixed costs are different from the fixed costs of establishing service facilities abroad \((F_{g})\). While fixed costs for upgrading the service quality involve additional costs after entry, such as costs on R&D, marketing, and advertisement activities, the form of fixed costs of establishing service facilities abroad are additional administrative burden on the headquarters associated with managing foreign facilities. In particular, it includes general investment costs for forming a subsidiary, distribution, and servicing network in a foreign country as well as the duplicate overhead service costs.

In all equations, the first superscript denotes firms’ choice of specific FDI pattern. In particular, H denotes horizontal FDI, a firm activity of replicating its production to foreign country to serve the local market, and represents a firm’s choice of producing in the host country by establishing a production facility. S denotes service FDI, a firm activity of replicating its services to foreign country to serve the local market, and represents a firm’s choice of producing at home and exporting to its service facility in the host country. Second superscript, on the other hand, denotes a firms’ choice of certain type of service managers where H represents home service managers and L represents local service managers.

Because all profit functions are continuous with respect to the firm productivity level, I can also use the intermediate value theorem to prove that there exists unique threshold \(\overline{\theta }\) that cuts off two profit functions.

While the Export–Import Bank of Korea has collected data officially on Korean-owned affiliates abroad since 2002, these figures are restricted from the public by the Ministry of Strategy and Finance of Korea for confidentiality reasons.

In the dataset, 92 countries are reported to be the destination of Korean FDI flows in 2011. To make it consistent with the theoretical model on studying firms’ decisions of serving high- and low-income countries, relative to home, I distinguish between firms that invest in a country that is more or less advanced than Korea based on whether its GDP per capita is higher or lower than that of Korea. As a result, 28 countries are classified as more advanced countries, while 64 countries are classified as less advanced countries. The list of these countries is reported in Table 6 in the “Appendix”.

According to the Export–Import Bank of Korea, top managers are defined as managers delegated from headquarters to appoint the overall performance of affiliates, whereas middle managers are defined as managers in charge of supervising production workers and, specifically, in charge of contracting with local production workers. Service managers are defined as managers outside the production line who are in charge of sales and after-service of the products.

Restricting the analysis to consider local market-oriented FDI firms whose affiliates only engage in local sales and employ service managers results in a loss of 14.6 % of FDI firms in the dataset.

Following Aw and Lee (2008), I compute labor productivity as \([(ln Q - \overline{ln} Q) - (ln L - \overline{ln} L)]\) where \(\overline{ln} Q\) and \(\overline{ln} L\) are the industry mean levels of the log of total revenue plus net inventory change and log of total employment.

Since the dataset on transport cost is difficult to obtain, prior trade literature have turned to indirect measures of transport cost by using data constructed from the matched partner technique, such as distance and ad valorem shipping costs calculated as trade partners’ CIF/FOB ratio. However, recent trade studies show that using these measures to proxy transport cost is not useful to measure cross-commodity variation. See Keller (2002) and Hummels and Lugovskyy (2006) for more detail.

While there exist a large number of studies that use English or French as a common official language to measure cultural difference between countries (Blonigen and Piger 2014; MacGarvie 2005; Tong 2005), Korean is not a very common first or second language spoken worldwide. Instead of using a common language, therefore, I compute Hofstede (1980) index to measure cultural distance between Korea and host countries. Hofstede (1980) index can be constructed as \({\sum _{i=1}^{4} \{(I_{ij}-I_{ik})^{2}/V_{i}}\} / 4\), where \(I_{ij}\) stands for the index for the ith cultural dimension of jth country, \(V_{i}\) is the variance of the index of the ith dimension, and k represents home country (Korea). See Hofstede and Hofstede (2005) for more detail on constructing indices of cultural distance between countries.

In particular, country’s infrastructure index is constructed as an average of three indicators: fixed line and mobile subscribers, internet users, and computers per 100 habitants in 2011.

Using an education level to capture managerial efficiency is difficult and problematic since some cultural aspects play a critical role in managerial efficiency. However, in the light of discussion from the previous section, the choice of employing local managers could be more influenced by the efficiency of local human capital (Antràs et al. 2006; Defever 2006).

In regards to firms’ production location choices, nearly 60 % of firms appear to produce in the host country, while nearly 40 % of firms produce in Korea and export to their service affiliates abroad. For providing services, on the other hand, nearly 70 % of firms tend to employ local service managers, while nearly 30 % of firms send Korean service managers to their affiliates abroad.

Following Tomiura (2007), I compute ATFP for each firm as \(ATFP = {\text {ln}}{\frac{Q}{L}} - {\frac{1}{3}}{\text {ln}}{\frac{K}{L}}\), where Q is firm’s value-added, L is total employment, and K is tangible fixed asset.

With these alternative measures, I also estimate firms’ choice of production locations with different types of service managers by using linear probability model. The estimates and significance of coefficients are approximately same as probit coefficients reported in Table 4. To save space, however, I do not report LPM results in the paper. LPM estimates from using alternative measures are available upon request.

The bivariate probit model provides a test for the positive correlation between firm’s decision to locate production in the host country and to provide services through local service managers conditional on the vector of covariates including explanatory and control variables used in the previous specification.

For the robustness check, Table 8 in the “Appendix” presents bivariate probit estimates from using alternative measures for firm productivity and country’s informal trade barriers. The estimates and significance of coefficients are approximately same as bivariate probit coefficients in Table 5. In particular, coefficients on popshare in columns (2) and (4) show that firms’ service managerial choices are significantly determined by the ethnic Korean population share. It indicates that firms are more likely to employ local service managers than transfer Korean service managers in high- or low-income countries where small Korean population are present. This result also suggests that narrow coethnic Korean networks in host countries induce firms to employ local managers to provide services.

This assumption reduces the number of cases that must be considered. For example, firms will never use a third production location to serve the South since it is never profitable to have export sales from this location by bearing additional fixed investment cost and transport cost. Alternatively, if a third country incurs the high production cost (e.g. same as the cost for producing in the North or Home), firms have no reasons to produce and export from this location by incurring additional investment cost and transport cost.

Consistent with Eqs. (13)–(16) and (21)–(24) in Sects. 2.1 and 2.2, the first superscript in all equations represents firms’ choice of production locations in terms of FDI patterns where the first superscript E in Eqs. (32) and (33) denotes export platform FDI, a firm activity of investing in the host country to produce and export to other foreign markets. The second superscript denotes firms’ choice of service managers between home and local (North) managers.

References

Ai, C., & Norton, E. C. (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economic Letters, 80(1), 123–129.

Antràs, P., Garicano, L., & Rossi-Hansberg, E. (2006). Organizing offshoring: Middle managers and communication costs (NBER Working Paper 12196). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Aw, B. Y., & Lee, Y. (2008). Firm heterogeneity and location choice of Taiwanese multinationals. Journal of International Economics, 76(2), 403–415.

Blonigen, B. A., & Piger, J. (2014). Determinants of foreign direct investment. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique, 47(3), 775–812.

Brainard, S. L. (1993). A simple theory of multinational corporations and trade with a trade-off between proximity and concentration (NBER Working Paper 4269). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Brainard, S. L. (1997). An empirical assessment of the proximity-concentration trade-off between multinational sales and trade. American Economic Review, 87(4), 520–544.

Crinò, R., & Epifani, P. (2009). Export intensity and productivity (Development Working Papers 271) Centro Studi Luca d’Agliano. Milan: University of Milan.

Debaere, P., Lee, H., & Lee, J. (2013). Language, ethnicity and intrafirm trade. Journal of Development Economics, 103(C), 244–253.

Defever, F. (2006). Functional fragmentation and the location of multinational firms in the enlarged Europe. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 36(5), 658–677.

Fajgelbaum, P., Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (2011). Income distribution, product quality, and international trade. Journal of Political Economy, 119(4), 721–765.

Greene, W. (2010). Testing hypotheses about interaction terms in nonlinear models. Economics Letters, 107(2), 291–296.

Grossman, G. M., Helpman, E., & Szeidl, A. (2006). Optimal integration strategies for the multinational firm. Journal of International Economics, 70(1), 216–238.

Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V. (1994). Organizing for knowledge flows within MNCs. International Business Review, 3(4), 443–457.

Hallak, J. C. (2006). Product quality and the direction of trade. Journal of International Economics, 68(1), 238–265.

Hallak, J. C., & Sivadasan, J. (2009). Firms’ exporting behavior under quality constraints (NBER Working Paper 13928). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Harzing, A.-W., & Noorderhaven, N. (2006). Geographical distance and the role and management of subsidiaries: The case of subsidiaries down-under. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(2), 167–185.

Helpman, E., Melitz, M. J., & Yeaple, S. R. (2004). Export versus FDI with heterogeneous firms. The American Economic Review, 94(1), 300–316.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations. Software of the mind. New York: McGrawHill.

Horstmann, J., & Markusen, J. R. (1992). Endogenous international market structures in trade. Journal of International Economics, 32(1), 109–129.

Hummels, D., & Lugovskyy, V. (2006). Are matched partner trade statistics a usable measure of transportation costs? Review of International Economics, 14(1), 69–86.

Ishikawa, J., Morita, H., & Mukunoki, H. (2010). FDI in post-production services and product market competition. Journal of International Economics, 82(1), 73–84.

Johnson, R. C. (2012). Trade and prices with heterogeneous firms. Journal of International Economics, 86(1), 43–56.

Keller, W. (2002). Geographic localization of international technology diffusion. The American Economic Review, 92(1), 120–142.

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(Fall), 411–432.

Krugman, P. R. (1983). The new theories of international trade and the multinational enterprise. The Multinational Corporation in the 1980s. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

MacGarvie, M. (2005). The determinants of international knowledge diffusion as measured by patent citations. Economics Letters, 87(1), 121–126.

Manasse, P., & Turrini, A. (2001). Trade, wages, and ‘superstars’. Journal of International Economics, 54(1), 97–117.

Maurin, E., Thesmar, D., & Thoenig, M. (2002). Globalization and the demand for skill: An export based channel (CEPR Discussion Paper 3406). London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Nocke, V., & Yeaple, S. R. (2007). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions vs. greenfield foreign direct investment: The role of firm heterogeneity. Journal of International Economics, 72(2), 336–365.

Qiu, L. (2010). Cross-border mergers and strategic alliances. European Economic Review, 54(6), 818–831.

Rauch, J. E., & Casella, A. (2003). Overcoming informational barriers to international resource allocation: Prices and ties. The Economic Journal, 113(484), 21–42.