Abstract

This short-term longitudinal study examined the association between relational and physical victimization and subsequent depressive symptoms together with the roles of social cognitive processes (i.e., relational interdependence) and gender in this association. A total of 580 Japanese adolescents in the seventh and eighth grades (52 % girls; age range 12–14) participated in this study across an academic year. Results of structural equation modeling demonstrated that relational and physical victimization, which was assessed via self- and teacher- reports, was concurrently associated with greater depressive symptoms, regardless of the gender of the youth and the level of relational interdependence. Furthermore, after controlling for the stability and co-occurrence between each construct, relational victimization (not physical victimization) was predictive of elevated depressive symptoms only for boys who exhibited relatively higher relational interdependence. The findings are discussed from developmental, gender, and cultural perspectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Considerable changes occur in cognitive, emotional, and social development from childhood to adolescence. Relative to younger children, adolescents typically spend increasing amounts of their time with peers, tend to exhibit more awareness from peers, and experience greater peer pressure [1]. They also exhibit higher levels of peer-oriented antisocial and disruptive behaviors [2] and develop more interpersonal stress within peer groups and friendships [3]. In general, focus on peer groups as the primary places for socialization leads to positive outcomes (e.g., acquiring leadership skills, prosocial behavior, and social competence through observational learning). However, negative interactions (e.g., conflicts, disagreements, and even victimization) commonly occur within a peer setting, and become a serious stressor detrimental to adjustment for some youth. The complex nature of peer relationships has developmental implications for clinicians, educators, and researchers in terms of how peer victimization influences the way adolescents think, feel, and behave.

To date, an extensive body of studies have investigated interpersonal problems within a peer group and documented the link between peer victimization and a host of mental health problems, including aggression, anxiety, and depression [4]. Although physical victimization (e.g., being hit, kicked, and punched by peers) has been somewhat widely examined, relational victimization, a form of peer maltreatment in which interpersonal relationships are used as an agent of harm (e.g., being excluded, ignored, and being a target of malicious rumors) has gained increased attention. A large body of research on relational and physical victimization and adjustment problems has been conducted in the Western cultures [5]. Although these studies produce promising findings in the area of research, their application, practice, and translation is culturally limited. This gap in the literature may be important because culture is thought to be a larger social context of development [6]. Hong and Espelage [7] suggest that individual-level factors for peer victimization can be fully understood only by considering cultural aspects of development, including cultural norms, beliefs, and values. Interdependence of relationships, which is central to Asian cultures, may constitute an interpersonally-oriented risk factor for the peer-linked stressors, putting youth at a greater risk for developing depressive symptoms [5, 8]. Notably, interdependence of relationships is more pronounced in Asian cultures than in Western cultures [9]. Research incorporating relational interdependence as a cultural index gives us more knowledge about cultural influences on peer victimization and adjustment. If we gain a better understanding of how cultural values change peer victimization processes, it would help us design culturally sensitive intervention and prevention programs for victimized youth. This study examined the association between relational and physical forms of peer victimization and the display of subsequent depressive symptoms together with the moderation of relational interdependence among Japanese adolescents. Possible gender differences in the frequency of relational and physical victimization and the moderation of relational interdependence also were examined.

Relational and Physical Victimization and Depressive Symptoms

Youth who are exposed to peer victimization of all forms are at an increased risk for internalizing adjustment problems (depression) compared to non-victimized youth [10]. Adolescent depression, in turn, has been shown to be associated with peer difficulties, including low social status, peer rejection, and isolation [11]. Experiences of peer victimization and the presence of depression may hinder the opportunity to acquire social skills and behaviors required for forming healthy relationships. Our continued effort to examine victimization and depression is crucial as it boosts the understanding of how we can increase positive social learning and reduce peer-linked adjustment problems among youth. Previous studies show that early and increasing peer victimization uniquely contributes to heightened depressive symptoms above and beyond other covarying factors such as overt and relational aggression [12]. Similarly, being a victim of bullying during middle childhood increased the likelihood of exhibiting extreme emotional and depressive responses during adolescence [13]. Further, studies using meta-analytic methods reported that peer victimization was linked to higher levels of depressive symptoms concurrently and longitudinally [10, 14].

Temporal and prospective links between peer victimization and developmental maladjustment have been established; however, a number of studies in this area have distinguished forms of peer victimization in terms of whether it is physical or relational. This separation has occurred, in part, because of the belief that each of these two forms of peer victimization is thought to follow its shared, different, and unique processes to depressive symptoms. Theory and research suggest that depressive symptoms among adolescents are generated primarily by interpersonally-oriented stress resulting from peer-linked stressors [3]. In turn, relational victimization is more interpersonal than physical victimization, indicating that relational victimization may be a stronger risk factor for depressive symptoms. This view is consistent with findings of empirical studies. For example, relational victimization seemingly is associated with depressive symptoms above and beyond that attributed to physical victimization among early adolescents [15], and this association is shown to be stronger than that of physical victimization [16]. In a study with a cluster analysis, youth being exposed to relational and poly-victimization exhibited a higher level of depression, alcohol, and drug use compared to non-victimized or minimally victimized youth [17]. Taken together, peer victimization, particularly relational victimization may create a severe environmental context in which youth are more likely to acquire and develop adjustment problems, including depressive symptoms over time.

The unique and stronger effect of relational victimization reflects the view that the victimized youth may follow different social-cognitive processes, depending on a form of peer victimization. Relationally victimized youth tend to exhibit distinct and undesirable social-cognitive patterns, including depressive thoughts, feelings of insecurity, and social incompetence. However, physically victimized youth did not display the same pattern [18, 19]. In addition, relationally victimized youth seemingly show more rumination (i.e., excessively discussing victimization experiences), which leads to more depressive symptoms [20]. These findings suggest that youth may be more vulnerable to relational victimization as it poses a stronger relational threat when viewed as being more aversive, more appalling, and more emotionally taxing compared to physical victimization. Yet, a majority of studies examining the link between relational and physical victimization and adjustment problems have been conducted in Western cultures. The present study was designed to examine the unique effect of relational victimization among non-Western Japanese adolescents. We conducted this study based on the belief that explicit replications with demographically different groups are a scientific method to increase the generalizability and applicability of the existing studies cross-culturally [21].

The Moderating Role of Relational Interdependence

Although links between forms of peer maltreatment and depressive symptoms have been established, we know little about why some victimized youth develop more depressive symptoms than their peers. One possible mechanism is that the youth may feel, think of, and react to relational and physical victimization differently, depending on their social-cognitive processes or patterns to relational contexts (i.e., relational interdependence). Relational interdependence is defined as the degree to which individuals include significant others in the mental representation of the self or who they are [22]. Thus, the youth with higher relational interdependence are thought to exhibit more interdependence in their close relationships than those with lower relational interdependence. Highly interdependent individuals tend to view close relationships more positively and care about their partners’ needs, beliefs, and expectation more seriously [22], which leads to sociability, satisfaction, and well-being within the relationships [23]. Furthermore, Chinese youth who are supportive of groups as a norm (i.e., interdependence of peer groups) are less likely to use aggression as a strategy to deal with peer conflicts, whereas those who endorse independence of self, which is manifested among Japanese youth similarly, tend to show more aggression [24].

However, the story may be different when highly interdependent individuals are exposed to interpersonally-oriented stressors. That is, they may be more likely to develop adjustment problems in a close relationship after a stressful event attributed to the relationship. Kawabata et al. [5] propose a relational-interdependent vulnerability model for developmental processes of peer victimization and depressive symptoms. This model posits that peer-linked negative contexts (i.e., peer victimization) and personal vulnerability (i.e., relational interdependence) interact to influence the development of psychopathology. As we discussed earlier, relational victimization constitutes a significantly greater relational threat and generates elevated interpersonal stress within a peer group. In turn, relational interdependence may create an additive interpersonal stress for developing adjustment problems when it is combined with peer-related stressors. Hence, relational victimization and relational interdependence may be a double threat for developing depressive symptoms among youth.

The Present Study

The goal of the present study was to examine the prospective association between relational and physical victimization and subsequent depressive symptoms and the moderating roles of relational interdependence and gender in this association among non-Western Japanese adolescents. We theorized that peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, would be associated with later depressive symptoms, and that this association would be stronger for highly interdependent adolescents. Specifically, we hypothesized that youth who experience relational victimization and who exhibit relatively higher levels of relational interdependence would be more likely to display depressive symptoms compared to their peers who also experience relational victimization yet display relatively lower levels of relational interdependence.

Rose and Rudolph [25] documented that relative to boys, girls place more emphasis on interpersonal relationships, develop greater interdependence on their peers, and tend to suffer from peer-oriented problems. It stands to reason that girls may display a higher vulnerability to relational aggression and victimization, which is predictably associated with internalizing adjustment problems, than boys [26]. On the other hand, Japanese children, regardless of gender, are thought to form relationships that are relatively closer, and acquiring relational interdependence is culturally normative [27]. Hence, boys and girls may be equally sensitive to relational threat, suggesting gender differences in terms of relational vulnerability may be less pronounced in the Japanese culture. Due to these mixed views, no specific priori hypotheses about the effect of gender were generated.

Method

Participants

Participants were 580 seventh and eighth grade adolescents (ages 12–14 years) from the classrooms in two public middle schools in a large Japanese city. Of the participants, were 243 fifth graders and 332 eighth graders and 276 boys and 299 girls (information about gender and grade was not reported for 5 participants). The socioeconomic status of the participants’ families was estimated to be lower-middle to middle-middle class based on school demographic information (i.e., the percentage of youth who were eligible for governmental financial support ranged from 17 to 22 % in the districts in which participating schools are located with the average of all public middle schools throughout the nation of 15 %). Parent consent forms were not obtained, consistent with traditional cultural constraints, governing research in Japanese schools. We followed this rule in order to be culturally appropriate in our interactions with the schools, teachers, and students. However, we fully discussed the purpose and procedure of the study, voluntary participation, and confidentiality with the teachers and school principals before collecting the data. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the second author’s university.

Procedure

Relational and physical victimization, depressive symptoms, and relational interdependence were assessed at two time points during a year. The first assessment was conducted at the beginning of a new academic year. Among the original participants, 528 adolescents (91 %) continued through the second assessment. All main variables did not differ between the discontinued sample and the remaining sample, F(1, 466) = 2.79, n.s., F(1, 466) = .641, n.s., F(1, 502) = 1.94, n.s., F(1, 499) = 1.06, n.s., for relational victimization, physical victimization, depressive symptoms, and relational interdependence, respectively. The number of participants differed among the tests due to the differences in the missing cases of each variable.

At each time point, participating students took part in a 1-h data collection session in the classroom. They were asked to complete questionnaires about their peer victimization experiences, depressive symptoms, and relational interdependence. The order of the questionnaires was counterbalanced per classroom to avoid an order effect. Classroom teachers were asked to complete a questionnaire about participating students’ relational and physical victimization. The language used in the assessment was Japanese. Measures to assess forms of aggression, depressive symptoms, and relational interdependence were translated into Japanese by an English–Japanese bilingual speaker and back-translated into English by an English–Japanese bilingual speaker.

Measures

Relational and Physical Victimization

Students’ relational and physical victimization was assessed, using the Children’s Social Experiences Questionnaire (CSEQ [8, 28]). Participants rated how frequently they had negative interactions with their peers, using a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (all the time). Items reflected physical victimization (four items; e.g., “You are hit by another peer”) and relational victimization (five items; e.g., “You are excluded from other peers”). To reflect relational victimization that occurs somewhat commonly among adolescents in the Japanese classrooms [29], four items that describe a more covert peer exclusion were added (“You are ignored by other peers”, “You are avoided by other peers”, “Your peers keep you away from other peers”, and “Your peers do not share a secret”). No items were added to physical victimization. Participants’ responses to each item were summed and averaged across the number of items to yield total scores on relational victimization and physical victimization (score range 1–5 for each form of peer victimization). Data from this measure demonstrated acceptable reliability at Time 1 and Time 2 (Cronbach’s αs for relational victimization = .86 and .91 and Cronbach’s αs for physical victimization = .78 and .78). The content, construct, and predictive validity of CSEQ for Japanese children has been assessed and confirmed in previous studies [8].

Students’ relational and physical victimization also were assessed by the Children’s Social Experiences Questionnaire-Teacher Report (CSEQ-T [30, 31]). Teachers were asked to rate each student on a 5-point scale based on how true each statement was. The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (always true). Relational and physical victimization were measured by three items (e.g., “This student gets hit by another peer”, “This student gets ignored by another peer”). Teachers’ responses to each item were summed and averaged across the number of items to yield total scores for relational and physical victimization (score range 1–5 for each). Data from these measures exhibited acceptable reliability at Time 1 and Time 2 (Cronbach’s αs for relational victimization = .85 and .87; Cronbach’s αs for physical victimization = .90 and .92). Similar to CSEQ, the validity of CSEQ-T for Japanese children has been established [31].

Self-reported and teacher-reported relational and physical victimization were standardized at each time point and combined to generate composite scores. Composite scores were used to capture a broader pattern of each form of peer victimization. Teachers are able to observe peer victimization of each student in the class, but may be unable to assess peer victimization outside the classroom and school. In contrast, students may be better able to observe peer victimization within the peer group, which are predictably closed and exclusive in nature during adolescence, and outside the classroom and school. In fact, there are at most moderate correlations between student-reported scores and teacher-reported scores (r = .50, p < .001 at Time 1 for relational victimization and r = .26, p < .01 at Time 1 for physical victimization). Hence, teachers and students may view somewhat different facets of relational and physical victimization, suggesting that incorporating both observers’ information maximizes the description of peer victimization.

Depressive Symptoms

Students’ depressive symptoms were assessed using the short version of Children’s Depression Inventory [32]. For each item, students were asked to rate statements about their thoughts and feelings during the past 2 weeks (e.g., “I feel like crying”, “I am sad”, “I do not have friends”). Students’ responses to each item were scored on a scale from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (always true), with higher scores representing greater depressive symptoms. Scores for the 11 items were summed to generate total depression scores (score range 5–55). In the present sample, the S-CDI displayed high internal consistency at both time points (Cronbach’s αs = .88 and .91, for Time 1 and Time 2, respectively).

Relational Interdependence

Students’ relational interdependence was assessed using the Relational-Interdependent Self-Construals for Children (RISC-C [5]). This measure was developed from the one designed to assess adults’ relational interdependence [22]. Sample items were “My relationships with friends are an important part of myself”, “When I think about myself, I often think of my close friends”, and “I feel proud of myself when my friends do nice things for other peers”. This measure’s 11 items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 5 = very much). The total score of the all items was used in the data analysis (score range 5–55). The data from this measure demonstrated acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s αs = .83 and .88 for Time 1 and Time 2, respectively).

Analytical Approach

We first examined gender and age differences in the frequency and short-term stability of study variables (i.e., relational victimization, physical victimization, depressive symptoms, and relational interdependence). Then, we conducted a correlational analysis and investigated whether major variables are related to one another within one time point and between two time points. These cross-sectional and longitudinal correlations would be the basis of a subsequent analysis of structural equation modeling (SEM).

A multi-group SEM was conducted using Amos 18.0 to examine associations between relational and physical victimization at Time 1 and depressive symptoms at Time 2 together with the possible moderating roles of relational interdependence and gender. Missing cases were handled by maximum likelihood estimation. Model fit was evaluated based on traditional statistical indices, including Chi-square statistics (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). In general, a good model fit shows non-significant Chi-squares, CFIs greater than .90, and RMSEAs less than .05 [33].

A hypothesized model included relational victimization, physical victimization, and depressive symptoms at Time 1 and Time 2. These variables were allowed to be correlated with each other to consider their co-occurrence. The model was specified with the paths from relational victimization and physical victimization at Time 1 to depressive symptoms at Time 2 while controlling for the paths from each construct at Time 1 to the construct at Time 2 (i.e., stability). Four groups (boys with higher interdependence, boys with lower interdependence, girls with higher interdependence, and girls with lower interdependence) were created using the median split of relational interdependence (median = 34) and gender. The model with unconstrained paths and that with constrained paths were compared across the groups after setting all hypothesized paths and the correlations among study variables to be equal.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

A within-subject ANCOVA was used to examine the frequency and short-term stability of relational victimization, physical victimization, depressive symptoms, and relational interdependence. Gender and grade served as between-subject variables. The assessment of study variables was nested within individuals or time. Thus, these variables served as within-subject variables. Multivariate tests concerning between-subject variables showed a significant main effect of gender in physical victimization, F(1, 402) = 143.70, p < .001, η 2 p = .26, indicating that, relative to girls, boys experienced more physical victimization. The results also showed the main effect of gender and grade in relational interdependence, F(1, 447) = 84.81, p < .001, η 2 p = .01; F(1, 447) = 33.32, p < .05, η 2 p = .02, for gender and grade, respectively. Higher levels of relational interdependence were exhibited by girls than boys and by eighth grade students than seventh grade students. Furthermore, grade differences occurred in levels of depressive symptoms, F(1, 445) = 11.40, p < .001, η 2 p = .03, with eighth grade students exhibiting higher levels of depressive symptoms than seventh grade students.

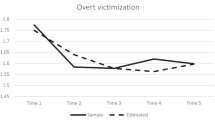

Multivariate tests regarding within-subject variables showed a significant interaction effect between time and gender on physical victimization, F(1, 402) = 4.83, p < .05, η 2 p = .01. Boys but not girls experienced more physical victimization at Time 1 than at Time 2. That is, between Time 1 and 2, the level of physical victimization decreased for boys only. No other significant effects were found. A lack of significant effect for relational victimization, depressive symptoms, and relational interdependence indicates that these variables did not change over time. The means and standard deviations are summarized in Table 1.

Correlational Analysis

Zero-order correlations are presented in Table 2. The relationships among the variables were small to moderate. For example, relational victimization at Time 1 was moderately related with depressive symptoms at Time 1 (r = .59, p < .001) and Time 2 (r = .34, p < .001), and physical victimization at Time 1 was somewhat related with depressive symptoms at Time 1 only (r = .20, p < .001). Moreover, the time-dependent stability of relational victimization, physical victimization, and depressive symptoms were moderate (rs = .44, .45, and .47, ps < .001, respectively). These findings supported the subsequent use of SEM.

The Model of Relational and Physical Victimization Predicting Depressive Symptoms and Moderating Roles of Relational Interdependence and Gender

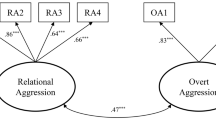

Results showed that the model with unconstrained paths fit the data adequately, χ2(16) = 32.529, p < .154, CFI = .978, RMSEA = .048 (90 % CI = .026–.070); however, the model with constrained paths fit the data less ideally, χ2(49) = 115.547, p < .001, CFI = .922, RMSEA = .052 (90 % CI = .040–.065). The deviance test of Chi-squares demonstrated that these models differed significantly from each other, Δχ2(33) = 81.018, p < .001, suggesting that the constrained paths differed across groups. A follow up pairwise comparison t test for each path of the group was conducted to determine which paths were statistically different. The path from physical victimization at Time 1 to physical victimization at Time 2 was stronger for boys with higher relational interdependence than boys with lower relational interdependence and girls with higher relational interdependence (t = 2.48, p < .01 and t = 3.14, p < .01, respectively). Additionally, the path from relational victimization at Time 1 to relational victimization at Time 2 (i.e., the stability of relational victimization) was stronger for boys with higher relational interdependence than girls with higher relational interdependence (t = 2.18, p < .05). Furthermore, the path from relational victimization at Time 1 to depressive symptoms at Time 2 differed statistically between boys with higher relational interdependence and other groups, including girls with higher relational interdependence, boys with lower relational interdependence, and girls with lower relational interdependence (t = 3.14, p < .01, t = 1.70, p < .10, and t = 1.62, p = .10, respectively). The path from physical victimization at Time 1 to depressive symptoms at Time 2 was significant for boys with lower relational interdependence only and the path estimates did not statistically differ among groups. Therefore, this finding was not interpreted. The results are summarized in Fig. 1.

The model predicting depressive symptoms from relational and physical victimization by relational interdependence and gender. Path coefficients are presented for boys with low relational interdependence, boys with high relational interdependence, girls with low relational interdependence, and girls with high relational interdependence in the order from left to right. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Discussion

The present study examined the associations between relational and physical peer victimization and subsequent depressive symptoms together with the moderation of relational interdependence and gender on these associations. After controlling for the stability and intercorrelations among study variables, relational victimization was found to predict depressive symptoms. This finding is consistent with previous Western studies showing that peer victimization, particularly relational victimization that poses a relational threat leads to developing depressive symptoms among youth. One possible explanation for this finding is that relational victimization is an interpersonally-oriented, stressful condition that allows young adolescents to form maladaptive social-cognitive processes about one’s self and others. Adolescents who suffer relational victimization tend to develop negative cognitive patterns, including depressive thoughts, feelings of inferiority, and hostile perceptions toward peers [18, 19]. In turn, biased cognitive processing can increase a risk for depression [34].

This study showed gender differences in physical victimization; that is, boys experienced higher levels of physical victimization than girls. This is consistent with the findings of previous studies which demonstrated the similar gender effect in Western cultures [25]. There may be a higher chance that boys become a target of physical aggression than girls in part because they are typically engaged in the same-gender peer groups associated with higher rates of physical aggression. Although relational aggression is thought to be typical of girls, gender differences in relational victimization were not found in this study. One possibility for this null finding is that relational aggression and victimization may commonly occur within the peer group regardless of gender, at least in Japan. Kitayama and Uskul [9] documented that people in Asian cultures are more relational-interdependent and less independent than those in Western cultures. Although Japanese culture becomes less traditional, it is still predominantly interdependently-oriented. Boys and girls are equally expected to place emphasis on peer groups and form friendships that are close and intimate, especially during adolescence. These relationships may be an unfavorable social context for acquiring relational aggression through observational learning and, in tandem, receiving relational victimization by peers for both genders.

There were gender and age differences in the level of relational interdependence. For example, girls showed higher levels of relational interdependence than boys. This finding is in line with the view that relative to boys, girls place more emphasis on interpersonal relationships, take into more consideration on significant others, and have more relationship-oriented goals [25]. These behavioral and social-cognitive patterns reflect the view that relationships are more central to the self among girls [25]. Moreover, older adolescents exhibited greater levels of relational interdependence than younger counterparts. This finding corresponds to the idea that adolescents become more independent from their parents and more dependent on their peers. They become affiliated with the peer group, which can be a “niche” that fits their interest, personality, and identity [1]. The focus on the peer group as a socializing milieu may increase adolescents’ relatedness to their peers, which contributes to the development of relational interdependence.

Age matters in the development of depressive symptoms. That is, children in the eighth grade showed higher levels of depressive symptoms than those in the seventh grade. Depressive symptoms are shown to be developed more severely in the context of interpersonal relationships, especially during adolescence [3]. In turn, peer groups and friendships can be developmentally more salient and become a stronger relational context for socialization [2]. This is in line with the finding that relative to younger counterparts, older adolescents exhibited more relational interdependence and more deeply mirrored close friends in the mental representation of the self. Higher relational interdependence may lead to more positive outcomes (e.g., happiness, satisfaction, well-being) along with high-quality relationships. However, when the quality of relationships is poor, the likelihood that the outcomes are undesirable (e.g., conflict, lack of support, interpersonal stress) is high. The combination of greater interpersonal stress and higher relational interdependence, which was revealed in this study, may heighten the feelings of depression during middle adolescence.

Further, the association between relational victimization and subsequent depressive symptoms was moderated by relational interdependence for boys only. That is, adolescent boys who experienced relational victimization and who exhibited relatively higher levels of relational interdependence were more likely to develop depressive symptoms than their same-gender peers with comparable levels of relational victimization and relatively lower levels of relational interdependence. This seems to be counterintuitive, given literature that suggests, relative to boys, girls are more vulnerable to developing internalizing symptoms when interpersonal problems in them occur [25]. However, this is the first study that showed the moderation effect of relational interdependence among adolescents. Replication in another population will make a more solid conclusion about the important role of relational interdependence. One possible mechanism is that adolescents, especially boys with higher levels of relational interdependence may be cognitively and emotionally more sensitive to experiences of peer victimization, especially relational victimization. For example, adolescent boys with higher relational interdependence and who are ignored, excluded, or treated as invisible by peers may be more likely to anticipate negative consequences of social interactions with peers, to degrade their self-evaluations, and to segregate themselves from the peer group. Relational victimization may occur even within close, dyadic relationships, including friendships independent of victimization by peers [35]. Highly interdependent boys may be more vulnerable than highly interdependent girls presumably because they may be more likely to view relational victimization by a close friend as conflictual, disloyal experiences and even to heighten feelings of betrayal and abandonment.

Another possible explanation is that highly interdependent boys may be viewed as being non-normative by their peers, given a lower rate of relational interdependence for boys. These interdependent boys may be subject to peer censure and become an easy target of relational aggression. This view is consistent with the finding that relational victimization (but not physical victimization) was more constant for boys with higher interdependence than girls with higher interdependence. Highly interdependent boys may be more likely to be stuck in a bully–victim relationship than interdependent girls. As a result, these at risk boys may suffer from aggressors in the same peer group. Overall, this finding suggests that although studies conducted in Western cultures document that girls are more vulnerable to relational aggression and victimization [26], boys also have the same risk when they are highly interdependent on their friends in Asian cultures such as Japan.

The finding regarding the negative effect of relational interdependence is novel. However, it may be debatable as to whether it is universal or context-specific. In other words, relational interdependence seemingly is associated with positive outcomes and yet the present study indicates that relational interdependence may predict depressive symptoms when it is coupled with relational victimization. These mixed views in fact suggest that relational interdependence can be either a protective or a risk factor, depending on the direction and quality of its associated social context. Interdependent adolescents may display optimal levels of adjustment when they form high-quality relationships. In contrast, they may follow maladaptive processes under interpersonal stress or threat such as relational victimization. Taken together, relational interdependence has differential influences on social and school adjustment problems, depending on the social context. It is advisable that parents, teachers, and practitioners understand the various roles of relational interdependence and pay special attention to the victims of relational aggression, especially when they are a boy and exhibit high levels of relational interdependence.

The present study informs that culturally and linguistically sensitive intervention and prevention programs can be considered to reduce relational victimization and its effect on depressive symptoms in a specific social context. Numerous intervention and prevention programs for bullying, aggression, and peer victimization have been designed and implemented in Western cultures [4]; however, cultural factors that may be unique to non-Western populations are rarely considered. In order to maximize the benefits of program implementation and minimize its costs, cultural processes and mechanisms for reducing aggression, victimization, and their effects on adjustment problems should be addressed. Based on the findings of this study, adolescents who develop a moderate level of relational interdependence and who keep a good balance between self and others show optimal development. In contrast, those who are overly dependent on their peers and who cannot act independently, when needed, may fail to achieve finest social, emotional, and educational outcomes. They would be mostly benefited from intervention and prevention programs. Future intervention programs for Japanese youth should include the assessment of relational interdependence and quality of relationships where it is formed.

Although this is beyond the scope of this study, academic pressure can be considered as a risk factor for peer victimization and depression. The literature suggests that youth are expected to attain high academic standards at school in respect to considerable parental and social pressure, particularly in Asian cultures [36]. Such academic pressure may be a serious threat to students who do not well on their academic performance. Students with lower achievement may be more likely to develop depressive symptoms if they experience peer victimization than their peers presumably because they find it difficult to go through a burden of double pressure (i.e., peer and academic pressure). On the other hand, students with high achievement may be less likely to exhibit depressive symptoms, if they suffer from peer victimization, as achievement serves as a buffer. A further investigation of how different types of stressors (social, cognitive, and academic) interact to predict depressive symptoms among youth is recommended.

Limitations

One limitation is the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings. Because this sample was drawn from urban, lower middle to middle class families, the results cannot be generalized to different socioeconomic statuses (extremely poor or upper-class families). Second, information regarding larger social contexts such as school districts, neighborhoods, and media was not gathered. This may be problematic because, based on Bandura’s social learning theory, social context may serve an important environment that facilitates or hinders the modeling effect of physically and relationally aggressive behaviors. Third, whereas the present study unraveled the interactive effects of relational victimization and relational interdependence, the long-term developmental processes behind these effects merit further investigation. Fourth, a wider range of age groups should be considered in a future study. Given that peer groups and friendships become more developmentally salient, the role of relational interdependence may be stronger for adolescents, compared to younger children. Fifth, the role of relational interdependence should be examined further cross-culturally. It is possible that the effect of relational interdependence may be more pronounced for adolescents in Asian cultures associated with greater emphasis on interdependence than those in Western cultures.

It is also important to note that there may be cross-informant variations in the ratings of relational victimization. The present study used a composite score of teacher-reported and adolescent-reported relational victimization. This approach is beneficial in part because the combined score may reflect a wider spectrum of relational victimization which is often subtle and indirect in nature. However, it may have a limitation in a statistical and analytical method. Using both scores together may cancel out the uniqueness of each informant’s rating. When the hypothesized model was analyzed by the informant, the only model specified by adolescent reports produced the statistical significance on the path from T1 relational victimization to T2 depressive symptoms, which was reported in the result section. Lack of a significant finding from a single teacher assessment implies an informant bias about the report of relational victimization. One possibility for this incongruity is that teachers’ observations of relational victimization may be limited to the classrooms, whereas adolescents’ observations include a broader range of relational victimization that may occur outside the schools. Non-classroom based relational victimization may be more frequent, more severe, and more stable in part because they mostly occur behind the teacher’s back. This type of relational victimization may be a stronger indicator of depressive symptoms than classroom-based relational victimization for adolescents, who typically spend more time with their peers after regular school hours (e.g., extracurricular activities, cram school). Overall, each informant may have a different statistical and practical implication and, thus, it would be advisable that the results are interpreted with caution.

Summary

Peer victimization is considered to be a risk factor for depressive symptoms. In particular, relational victimization seems to be more strongly linked to depressive symptoms than physical victimization [5]. This is presumably because relational victimization that is an origin of interpersonal stress coincides with the onset of depression among adolescents. Yet, relatively little is known about how and why this negative process occurs for Asian youth. This short-term longitudinal study addressed this gap in the literature and examined the association between relational and physical victimization and depressive symptoms together with the moderating roles of social cognitive processes (i.e., relational interdependence) and gender in this association among Japanese youth.

Results showed that relational and physical victimization was concurrently associated with greater levels of depressive symptoms for boys and girls. After controlling for the stability of each construct, relational victimization was predictive of elevated depressive symptoms only for boys with higher relational interdependence. This effect was not found for physical victimization regardless of gender. These findings suggest that peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, in the combination with relational interdependence may be a risk factor for developing depressive symptoms among Japanese boys.

References

Steinberg L (2009) Adolescent development and juvenile justice. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 5:459–485. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153603

Dishion TJ, Tipsord JM (2011) Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annu Rev Psychol 62:189–214. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100412

Rudolph KD (2008) Developmental influences on interpersonal stress generation in depressed youth. J Abnorm Psychol 117:673–679. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.673

Card NA, Hodges EE (2008) Peer victimization among schoolchildren: correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. Sch Psychol Q 23:451–461. doi:10.1037/a0012769

Kawabata Y, Tseng W-L, Crick NR (2014) Mechanisms and processes of relational and physical victimization, depressive symptoms, and children’s relational-interdependent self-construals: implications for peer relationships and psychopathology. Dev Psychopathol 26:619–634. doi:10.1017/S0954579414000273

Bronfenbrenner U (1979) The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Hong JS, Espelage DL (2012) A review of research on bullying and peer victimization in school: an ecological system analysis. Aggress Violent Behav 17:311–322

Kawabata Y, Crick NR, Hamaguchi Y (2013) The association of relational and physical victimization with hostile attribution bias, emotional distress, and depressive symptoms: a cross-cultural study. Asian J Soc Psychol 16:260–270. doi:10.1111/ajsp.12030

Kitayama S, Uskul AK (2011) Culture, mind, and the brain: current evidence and future directions. Annu Rev Psychol 62:419–449. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145357

Cook CR, Williams KR, Guerra NG, Kim TE, Sadek S (2010) Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic investigation. Sch Psychol Q 25:65–83. doi:10.1037/a0020149

Kochel KP, Ladd GW, Rudolph KD (2012) Longitudinal associations among youths’ depressive symptoms, peer victimization, and low peer acceptance: an interpersonal process perspective. Child Dev 83:637–650. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01722.x

Rudolph KD, Troop-Gordon W, Hessel ET, Schmidt JD (2011) A latent growth curve analysis of early and increasing peer victimization as predictors of mental health across elementary school. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 40:111–122. doi:10.1080/15374416.2011.533413

Zwierzynska K, Wolke D, Lereya TS (2013) Peer victimization in childhood and internalizing problems in adolescence: a prospective longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 41:309–323. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9678-8

Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ (2010) Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse Negl 34:244–252. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009

Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Trevaskis S, Nesdale D, Downey GA (2014) Relational victimization, loneliness and depressive symptoms: indirect associations via self and peer reports of rejection sensitivity. J Youth Adolesc 43:568–582. doi:10.1007/s10964-013-9993-6

Hoglund WL (2007) School functioning in early adolescence: gender-linked responses to peer victimization. J Educ Psychol 99:683–699. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.4.683

Espelage DL, Low S, De La Rue L (2012) Relations between peer victimization subtypes, family violence, and psychological outcomes during early adolescence. Psychol Violence 2:313–324

Cole DA, Dukewich TL, Roeder K, Sinclair KR, McMillan J, Will E et al (2014) Linking peer victimization to the development of depressive self-schemas in children and adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol 42:149–160. doi:10.1007/s10802-013-9769-1

Sinclair KR, Cole DA, Dukewich T, Felton J, Weitlauf AS, Maxwell MM et al (2012) Impact of physical and relational peer victimization on depressive cognitions in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 41:570–583. doi:10.1080/15374416.2012.704841

Mathieson LC, Klimes-Dougan B, Crick NR (2014) Dwelling on it may make it worse: the links between relational victimization, relational aggression, rumination, and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Dev Psychopathol 26:735–747. doi:10.1017/S0954579414000352

Duncan GJ, Engel M, Claessens A, Dowsett CJ (2014) Replication and robustness in developmental research. Dev Psychol 50:2417–2425. doi:10.1037/a0037996

Cross SE, Bacon PL, Morris ML (2000) The relational-interdependent self-construal and relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 78:791–808. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.791

Mattingly BA, Oswald DL, Clark EM (2011) An examination of relational-interdependent self-construal, communal strength, and pro-relationship behaviors in friendships. Pers Individ Dif 50:1243–1248. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.02.018

Li Y, Wang M, Wang C, Shi J (2010) Individualism, collectivism, and Chinese adolescents’ aggression: intracultural variations. Aggress Behav 36:187–194. doi:10.1002/ab.20341

Rose AJ, Rudolph KD (2006) A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychol Bull 132:98–131. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98

Crick NR, Zahn-Waxler C (2003) The development of psychopathology in females and males: current progress and future challenges. Dev Psychopathol 15:719–742

Rothbaum F, Pott M, Azuma H, Miyake K, Weisz J (2000) The development of close relationships in Japan and the United States: paths of symbiotic harmony and generative tension. Child Dev 71:1121–1142

Crick NR, Grotpeter JK (1996) Children’s treatment by peers: victims of relational and overt aggression. Dev Psychopathol 8:367–380

Sakurai Y, Kohama S, Arai K (2005) Relational aggression of tendency among preadolescents: conformity and students adjustment. Bull Tsukuba Dev Clin Psychol 17:39–44

Cullerton-Sen C, Crick NR (2005) Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: the utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social–emotional adjustment. Sch Psychol Rev 34:147–160

Kawabata Y, Crick NR, Hamaguchi Y (2010) Relational aggression, physical aggression, and social–psychological adjustment in a Japanese sample: the moderating role of positive and negative friendship quality. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38:471–484. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9386-1

Kovacs M (1985) The children’s depression inventory. Psychopharmacol Bull 21:995–998

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6:1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Gotlib IH, Joormann J (2010) Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 6:285–312. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305

Brendgen M, Girard A, Vitaro F, Dionne G, Boivin M (2015) The dark side of friends: a genetically informed study of victimization within early adolescents’ friendships. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 44:417–431. doi:10.1080/15374416.2013.873984

Tan JB, Yates S (2011) Academic expectations as sources of stress in Asian students. Soc Psychol Educ 14:389–407

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kawabata, Y., Onishi, A. Moderating Effects of Relational Interdependence on the Association Between Peer Victimization and Depressive Symptoms. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 48, 214–224 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0634-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0634-7