Abstract

The present study examined developmental changes in forms of peer victimization and longitudinal associations between forms of peer victimization and internalizing problems among Japanese adolescents. Participants were 271 students (Time 1 M age = 12.72, SD = 0.45, 50% girls) from 9 classrooms and 2 public middle schools in Japan. Data were collected at five time points from 7th to 9th grade. Growth curve modeling (GCM) of mean changes indicated that relational victimization and internalizing problems decreased over three school years. Overt victimization first decreased and then remained relatively constant toward the end of the assessment. In addition, the results of the Random Intercept Cross-Lagged Panel Model (RI-CLPM) indicated that the random intercept of relational victimization was positively and strongly correlated with that of internalizing problems. Although the random intercept of overt victimization was positively correlated with that of internalizing problems, the effect size was small to moderate. In general, there were no significant within-person changes between relational and overt victimization and internalizing problems. However, some exceptions were noted towards the end of middle school, such that higher relational victimization was associated with increases in internalizing problems, which in turn led to more relational victimization. There were no gender differences in the above trajectories or in the transactional models. The findings regarding at-risk youth who are vulnerable to relational and overt victimization are discussed from clinical, cultural, and developmental perspectives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multiple changes occur during the transition from late childhood to adolescence, including becoming more independent from parents, expanding social activities and networks, and increasing time spent in school (Smetana et al., 2015). In particular, adolescents spend more time with their peers than younger children. Peer interactions often provide a positive socializing context for adolescents to acquire social information and skills necessary to form healthy peer relationships (Smetana et al., 2015). However, negative interpersonal experiences and stress, such as overt and relational victimization, can result from hostile interactions with peers. Overt victimization is defined as the experience of physical and verbal aggression (e.g., being hit, kicked, or called names). Relational victimization is the experience of relationally aggressive acts intended to harm an individual’s relationships (e.g., being ignored, excluded from social activities, and treated as invisible; Casper & Card 2017; Ostrov & Kamper 2015). Overt and relational victimization have been shown to be detrimental to adolescents’ mental health. Overt victimization is predictive of overt aggression, and relational victimization is more strongly associated with internalizing adjustment problems (Casper & Card 2017).

Despite the evidence supporting the correlates and consequences of overt and relational victimization, much more research is needed in this area. According to Casper and Card (2017), there is much more knowledge about peer aggression than peer victimization among children and adolescents. This view is partially supported by Orpinas et al.’s (2015) review, which indicates that many more studies have been published on relational aggression than on relational victimization. Historically, peer victimization has not been differentiated based on its form. As a result, the majority of studies in this area have primarily examined physical, verbal, overt (i.e., the combination of physical and verbal victimization), or composite peer victimization (i.e., all forms of physical, verbal, and relational victimization). To date, however, a growing number of studies have examined the unique role of relational victimization either by itself or in contrast to other forms of victimization (e.g., Cho et al., 2022; Giesbrecht et al., 2011; Marsh et al., 2016; Ostrov & Godleski 2013; Tampke et al., 2019). This trend is promising. Relational victimization has been shown to be conceptually distinct from overt victimization (Kawabata 2020) and linked to biological, physiological, cognitive, emotional, and social factors above and beyond overt victimization (Calhoun et al., 2014; Williford et al., 2019). For example, in a meta-analytic study, Casper and Card (2017) found that relational victimization, but not overt victimization, was associated with higher internalizing problems and lower peer support. This finding suggests that different pathways lead from forms of peer victimization to social-psychological adjustment.

Furthermore, research on peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, has been conducted in Western societies, potentially leaving a gap in the literature regarding the important role of cultural context in relational victimization (Kawabata 2018). This limitation has been echoed by leading scholars who advocate for the inclusion of sociocultural context in the study of peer victimization (Ostrov & Kamper 2015) and psychopathology (Causadias 2013). Extending the study of forms of peer victimization to non-Western populations strengthens cross-cultural perspectives on child and adolescent psychopathology. It also confirms the scientific rigor of existing studies and, at the same time, increases the significance of diversity science in psychology (Syed & Kathawalla 2022). Indeed, our knowledge of developmental changes in overt and relational victimization and the bidirectional, transactional associations with internalizing problems in non-Western adolescents is largely lacking. The present study was conducted to address this gap in the literature and to advance cross-cultural understanding of forms of peer victimization and their adjustment problems.

Developmental Changes of Forms of Peer Victimization

The majority of studies in this area of research, conducted in Western cultures, have examined the developmental changes or trajectories of overt and relational aggression (perpetrators of aggression) during adolescence. A longitudinal study by Farrell et al. (2018) showed that along with physical aggression, relational aggression decreased in each grade of middle school (sixth, seventh, and eighth grades). Similarly, Orpinas et al. (2015) found three trajectories of relational aggression (low, moderate, and high decreasing) and that levels of relational aggression decreased across all trajectories. Only a few studies of overt and relational victimization conducted in Western cultures showed that peer victimization, which includes both physical and relational forms, decreased for each grade of middle school (Farrell et al., 2018). Likewise, similar to relational aggression, Orpinas et al. (2015) demonstrated three trajectories of relational victimization (low, moderate, and high decreasing), all of which showed a decline in relational victimization from grades 6 to 12. These findings suggest the possibility that levels of overt and relational victimization may decrease over the course of development.

This view is largely consistent with a review by Meeus (2016), who suggests that social, cognitive, and behavioral changes from middle adolescence onward are normative and that the changes may be partly due to maturation. These changes include personality and identity development, caring and support from friends, a stable peer group, and decreased behavioral problems such as aggression and delinquency (Meeus 2016). Interestingly, however, Meeus’s review notes that social anxiety and depressive symptoms increase from adolescence to adulthood. This is partly because older children and adolescents are required to think about their peer groups, friendships, and even romantic relationships as a whole. The complexity of interpersonal relationships and an expanded social network may provide the negative socializing context for increased social anxiety and depressive symptoms for some adolescents. Overall, given Meeus’ view, it is possible that relational and overt victimization may decrease during adolescence. In contrast, internalizing problems may increase over the course of development.

The Association between Forms of Peer Victimization and Internalizing Problems

Older children and adolescents place greater emphasis on relationships. Negative experiences, such as overt and relational peer victimization, can lead to poor self-evaluations that result in adjustment difficulties and pose developmental risks (Crick & Bigbee 1998). Thus, their vulnerability to negative peer experiences and internalizing problems may be heightened during this developmental period (Prinstein & Giletta 2020). The interpersonal vulnerability model of internalizing problems, such as depressive symptoms, posits that disruptions or difficulties in relationships (e.g., relational victimization) may increase the risk of such internalizing problems. In turn, the presence of internalizing problems weakens interpersonal functioning, leading to the development of internalizing problems (Hankin et al., 2010; Rudolph et al., 2008). Such transactional vulnerability parallels the biological changes that are salient for adolescents. Adolescents tend to be vulnerable or hypervigilant to peer adversity and stress, especially social exclusion, which is part of relational victimization and often activates different regions of the brain in the face of threat (Pagliaccio et al., 2023; Will et al., 2016).

Collective evidence supports the bidirectional, transactional model of forms of peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, and internalizing problems, including anxiety and depression. In a study examining the reciprocal longitudinal association between peer victimization and depression in American adolescents, depressive symptoms predicted changes in both relational and physical victimization, but these forms of peer victimization did not predict changes in depressive symptoms (Tran et al., 2012). The results of this study support a symptom-driven model of peer victimization, which posits that the behavior of individuals with internalizing symptoms increases the likelihood of peer victimization by eliciting negative reactions from others (Tran et al., 2012; Sentse et al., 2017). However, a new, larger longitudinal study by Cho et al. (2022) provides additional, unique information about the bidirectional associations between relational victimization and depressive symptoms among ethnically diverse youth. Results of the study showed that relational victimization predicted future depressive symptoms, and at the same time, depressive symptoms predicted changes in relational victimization. A recent meta-analytic study confirmed the reciprocal relationships between forms of peer victimization and internalizing problems, although the effect sizes were rather small (rs ranged from.18 to.19; Christina et al., 2021). Overt victimization has also been found to predict internalizing problems such as depressive symptoms, but more strongly with behavioral problems such as aggression and substance use (Casper & Card 2017; Fite et al., 2016).

The Context of Japanese Culture

Japan may be a unique sociocultural context in which to study peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, and mental health problems. Contemporary Japanese culture is more Westernized than it used to be, but it is still predominantly a group-oriented society (Hamamura 2012). In such a culture, individuals prioritize maintaining harmony within their groups, which creates solidarity among them (Davies & Ikeno 2002). Given the group orientation of Japanese culture, peer victimization, especially relational victimization, may be detrimental to students’ mental health (Kawabata 2018). Such mental health problems may be exacerbated, especially in Japanese middle schools, which are more socially and academically demanding than elementary schools, which are more protective (Le Tendre & Fukuzawa, 2001). According to Toda (2016), ijime (similar to the term “bullying”) has been a major problem in schools since the 1980s and is an act carried out collectively by a group of students to target another student. Ijime is typically embedded in peer relationships. It often takes indirect and relational forms (e.g., being ignored and isolated from the peer group), resulting in more psychological than physical harm to victims (Murayama et al., 2015). Over the past decades, the number of studies examining the nature (e.g., frequency and severity) of ijime has increased rapidly (Osuka et al., 2019; Toda 2016). However, the understanding of a specific form of peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, and its correlates and consequences for youth remains limited in Japan (Kawabata 2018).

The cultural values that Japanese individuals typically endorse may, in part, influence how relationally victimized adolescents exhibit internalizing problems. Japan consists of many interdependent groups characterized by a conscious understanding of each other without words (Davies & Ikeno 2002). People in Japan typically use concepts to categorize others in relation to themselves, such as uchi, which includes individuals with whom they share a conscious understanding, and soto, which includes individuals who do not share this common understanding and are treated as outsiders (Davies & Ikeno 2002). Relational victimization may lead Japanese students to view themselves as outsiders and prevent them from developing an appropriate self-concept, well-being, and healthy friendships (Kawabata et al., 2010). Being viewed as an outsider by peers in the classroom (i.e., relational victimization) may be detrimental to adolescents’ social and school adjustment, especially for students in a culture where the interdependence of relationships is developmentally important (Kawabata et al., 2014).

Such interpersonal vulnerability to relational victimization and internalizing problems among non-Western youth has been examined in previous studies. In a cross-cultural, cross-sectional study of relational victimization and depressive symptoms among European American and Japanese children (n = 272, ages 9–10), the relationship between relational victimization and internalizing problems, such as depressive symptoms, was significant only for Japanese children (Kawabata 2018). In addition, Kawabata et al. (2014) found that relational victimization, but not physical victimization, predicted relative increases in internalizing problems, such as depressive symptoms, only for children with high levels of relational interdependence in Taiwan. Specifically, this study showed that relational interdependence-the degree to which children view their friends as themselves-moderated the association between relational victimization and depressive symptoms. Highly interdependent children are thought to care about their friends and are more likely to respond to peer evaluations, whether positive or negative. Relational victimization reflects negative peer evaluation, and these children may be vigilant or sensitive to it at school, making them psychologically vulnerable when they experience aversive peer interactions (Kawabata 2018).

The Present Study

Previous studies have demonstrated developmental changes in forms of peer victimization and their associations with internalizing problems largely in Western populations. However, our knowledge of adolescent peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, in a non-Western cultural context remains quite limited. More studies, particularly larger longitudinal studies, in this area of research are needed to fully understand the developmental changes and long-term consequences of relational victimization among youth living in non-Western cultures. A relatively large number of studies have examined bullying or ijime, which includes all forms of peer victimization, in Japan. The results of these studies indicate the prevalence of bullying in Japanese middle schools, which is promising. However, they may obscure the differences among forms of peer victimization and their associations with social psychological adjustment problems, such as internalizing problems. Knowledge gained from the present study will provide useful information that can make parents, school professionals, and practitioners aware of the differential changes and influences of forms of peer victimization. Using three-year longitudinal data and advanced statistical tools (growth curve modeling and random intercept cross-lagged panel model), we examined 1) developmental changes in overt and relational victimization and internalizing problems, and 2) the longitudinal, bidirectional associations between overt and relational victimization and internalizing problems.

Based on the literature review, we hypothesized that overt and relational victimization, along with internalizing problems, would change or most likely decrease over the course of development. We also hypothesized that after controlling for gender, peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, would co-occur with internalizing problems. That is, peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, would be associated with higher internalizing problems at all time points across years. In addition, we hypothesized that peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, would be associated with changes in internalizing problems and that higher internalizing problems would precede more relational victimization.

Gender should also be considered in the study of relational and overt victimization. Previous studies with Western samples show gender differences in the frequency of forms of peer victimization. Girls are more exposed to relational victimization than boys, and boys tend to experience more overt victimization than girls (Orpinas et al., 2015; Rose & Rudolph 2006). However, a meta-analytic study found no gender differences in relational victimization (Casper & Card 2017). Despite the mixed findings, the collective evidence points to the critical role of gender in relational and overt victimization. The present study examined gender differences in mean changes in the study variables and the bidirectional associations between forms of peer victimization and internalizing problems.

Method

Participants

Participants were 271 students (Time 1 M age = 12.72, SD = 0.45, 50% girls) recruited from 9 classrooms and 2 public middle schools in a large city in west-central Japan. Data were collected at five time points from grade 7 to grade 9 (Time 1, G7 winter; Time 2, G8 summer; Time 3, G8 winter; Time 4, G9 summer; Time 5, G9 winter). The socioeconomic status (SES) of the participant’s family was estimated to be lower middle class to middle class based on available demographic information. The average number of residents in the city who received the supplemental government welfare plan was three times higher than the national average (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare 2020).

Measures

Relational Victimization

Participants’ relational victimization was assessed using Umezu et al.’s (2012) relational victimization scale, which was developed to measure relational victimization among Japanese adolescents. Four relational victimization items (being left out, being ignored, being the target of rumors, and silent treatment) that Japanese middle school students often experience at school were used in the present study. In selecting the four items, we referred to existing scales of relational victimization (The Social Experience Questionnaire-Self Report Form-SEQ-S; Crick & Grotpeter 1996; The Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire-RPEQ; Prinstein et al., 2001). We then ensured that the meanings of each of the four relational victimization experiences for adolescents in Japan were equivalent to those in the United States. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true). Sample items included “A teen ignored me,” “A teen left me out of the peer group,” and “A teen did not talk to me on purpose”.) Item scores were summed and divided by the number of items to obtain a mean score. The measure was found to be internally consistent in the current samples of adolescents, with alphas ranging from 0.72 to 0.82 across five time points (Table 1). Longitudinal confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the four-item, one-factor model of relational victimization was a good fit across five time points (see Fig. S1 and Table S1).

Overt Victimization

Participants’ overt victimization was assessed using the Self-report of Behaviors in Bullying (2 items; Pozzoli & Gini 2010). Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true). Items included “I was hit or pushed by my peers” and “I was called mean names.”) Item scores were summed and divided by the number of items to obtain an average score. The measure was found to be internally consistent in the current samples of adolescents, with alphas ranging from 0.64 to 0.90 across five time points (Table 1). Longitudinal confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the two-item, one-factor model of overt victimization was an adequate fit (see Fig. S1).

Internalizing Problems

Participants’ internalizing problems (anxiety and depressive symptoms) were assessed using the Japanese version of the Youth Self-Report of the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (Achenbach & Rescorla 2001). Among a full set of items, several items (e.g., suicidality) were removed due to cultural constraints; that is, the schools requested that the items be removed because they felt that the items were extremely sensitive. 11 items were used in the present study. Responses were rated on a 3-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all true) to 2 (very true). Item scores were summed and divided by the number of items to obtain the mean, which was used for the analysis. The measure was found to be internally consistent in the current samples of adolescents, with alphas ranging from 0.79 to 0.84 across five time points (Table 1). Scores on internalizing problems have been correlated with clinical diagnoses of major depression in both community and clinical samples (Achenbach 2019; Funabiki & Murai 2017).

Procedure

Two middle schools were randomly selected from several school districts in the urban area. After these schools agreed to participate, the researchers visited these schools and explained to the principals the importance of the study, confidentiality, voluntariness, and ethical considerations such as the protection of privacy and personal information. With the consent of the school principals, the parents of the students were given a brief meeting to inform them of the study and to obtain their consent. They were also provided with a summary of the study and ethical considerations to solicit their participation. In the assessment phrase, classroom teachers were asked to read the cover letter, assent form, and debriefing form, which included the nature of the study, student confidentiality, and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. These forms also included the researchers’ contact information and the availability of free psychological services if the survey caused participants emotional or mental distress. There was no more than minimal risk involved in the study. After assent was obtained from the students, the questionnaires were distributed during class time. The data collected were stored on a password-protected computer, and only researchers had access to them. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Konan University, Japan.

Data Analysis Plan

Prior to the main analysis, we conducted a missing data analysis to ensure that the missing cases were at random. We first used Little’s MCAR test (Little 1988) to analyze missing data. Missing cases ranged from 1.2% to 9.6% across study variables and time points (see Table 1). Their randomness across time points was assessed using Little’s MCAR test, χ2 = 47.19, p = 0.305; χ2 = 64.34, p = 0.10; χ2 = 47.52, p = 0.294, for relational victimization, overt victimization, and internalizing problems, respectively. The results suggest that missing cases at all time points are likely to be completely at random (Little 1988).

We also created two groups with respect to missing cases: a group with missing cases and a group without missing cases based on the Time 1 data. We then conducted a series of t-tests to examine whether the means of the study variables differed between these two groups at Time 2, Time 3, Time 4, and Time 5. Results for internalizing problems showed no group differences at any time point [Time 2 (t = −0.23, p = 0.822), Time 3 (t = 0.03, p = 0.975), Time 4 (t = 0.67, p = 0.512), and Time 5 (t = 0.51, p = 0.619)]. Results for relational victimization showed the same results - no group differences at any time point [Time 2 (t = 0.25, p = 0.808), Time 3 (t = −0.56, p = 0.585), Time 4 (t = 0.44, p = 0.665), and Time 5 (t = 0.45, p = 0.658)]. Again, there were no group differences for overt victimization [Time 2 (t = −0.20, p = 0.842), Time 3 (t = 0.12, p = 0.906), Time 4 (t = −0.33, p = 0.741), and Time 5 (t = −0.92, p = 0.362)]. The results established the premise that in the current study, maximum likelihood estimation (ML) can be used to handle missing cases.

To address the first goal of the present study, or to examine the developmental trajectories of relational victimization, overt victimization, and internalizing problems over the course of three academic years, we used growth curve modeling (GCM). To further examine whether the trajectories of these study variables differ or are similar between boys and girls, we conducted multi-group growth curve modeling with the intercepts and slopes of the trajectories constrained to be equal between boys and girls. Because the first and second models are nested, the chi square deviance test was used to compare the model fit of the two models. If the changes in model fit are statistically significant, it indicates that the multi-group model is better than the initial model. Thus, we can interpret that there are gender differences in the trajectory of the variable and report different intercepts and slopes for boys and girls. If the changes are not statistically significant, this suggests that there are no gender differences in the trajectory of the variable. In this case, the results of the initial model are interpreted and reported in this manuscript.

We also conducted a random intercept cross-lagged panel model (RI-CLPM) to address the second goal of the present study, or to assess the stability of the study variables and the cross-lagged, transactional associations between them. We tested a model that included an observed variable of relational victimization from Time 1 to Time 5, observed variables of internalizing problems from Time 1 to Time 5, and gender as a covariate. Specifically, we assessed the stability of relational victimization and internalizing problems (e.g., the path between relational victimization at Time 1 and relational victimization at Time 2) and the within-person cross-lagged paths between relational victimization and internalizing problems (e.g., the path from relational victimization at Time 1 to internalizing problems at Time 2, and the path from internalizing problems at Time 1 to relational victimization at Time 2). The within-time covariances between relational victimization and internalizing problems were freely estimated. We also considered the same model for overt victimization. To examine gender differences, we conducted a multigroup RI-CLPM. Again, we used the chi square deviance test to compare the two nested models.

To evaluate model fit, we used Hu and Bentler’s (1999) guidelines: closer to or greater than 0.95 for the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), 0.06 or less for the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and 0.05 or less for Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). Observed means of all variables were used in all analyses. Analysis of missing data was performed using the SPSS, and the analyses of GCMs and RI-CLPMs were performed using Mplus 8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017). To interpret effect sizes, we followed Cohen’s conventional guidelines, which recommend r = 0.10, r = 0.30, and r = 0.50 for weak, moderate, and strong correlations, respectively (Cohen 2016).

Results

Correlational Analysis

Results of the correlational analysis indicated that relational victimization was positively, consistently, and robustly correlated with internalizing problems within and across five time points. Overt victimization was also positively correlated with internalizing problems. However, these correlations were not consistent across time points, and in fact, some of the correlations were not significant. Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics and correlations with statistical significance among all study variables.

Growth Curve Modeling (GCM)

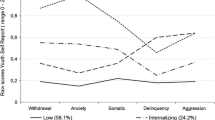

Relational Victimization

We first estimated the growth curve model with intercept and slope (linear) of relational victimization. This model fit the data adequately, χ2 (10) = 15.96, p > 0.10, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.05, N = 271. The estimates of the intercept and slope were significant, β = 2.93, p < 0.001, β = −0.30, p < 0.01, for intercept and slope, respectively. This suggests that the initial level of relational victimization was different from zero and steadily decreased over the course of three academic years (Fig. 1). To further examine whether the trajectories of relational victimization differed between boys and girls, a multi-group growth curve model was run. The model fit the data still adequately, χ2 (20) = 30.86, p < 0.10, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.06, N = 271. The Chi-square deviance test was performed to ensure that the first model was not better than the second, multi-group model. The results confirmed a non-significant change in the fit of the second model, χ2∆ (10) = 14.09, p > 0.10. Thus, there were no gender differences in the above trajectories.

Overt Victimization

Similar to relational victimization, we first estimated the growth curve model with intercept and slope (linear) of overt victimization. This model fit the data less well than we expected, χ2 (10) = 37.02, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.10, SRMR = 0.07, N = 271. Based on the observed mean differences, the changes did not appear to be linear. A quadratic term was then added to the model. The fit of the second model was better, χ2 (6) = 16.68, p < 0.05, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.06, N = 271. The estimates of the intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope were significant, β = 2.40, p < 0.001, β = −0.33, p < 0.05, and β = 0.21, p < 0.05, for the intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope, respectively. Given the better model fit and the significant higher order term, the quadratic model was interpreted as the final model. Levels of overt victimization appeared to initially decrease and then stabilize over the course of the remaining academic years (Fig. 1). The multigroup model fit was found to be good, χ2 (12) = 21.89, p < 0.05, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.07, N = 271. The Chi-square deviance test showed no significant change in the fit of the second model, χ2∆ (6) = 5.21, p > 0.50, indicating no gender differences in overt victimization.

Internalizing Problems

We again estimated the growth curve model with intercept and slope (linear) of internalizing problems. The model fit was good, χ2 (10) = 17.34, p < 0.10, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.03, N = 271. The estimates of the intercept and slope were significant, β = 2.32, p < 0.001, β = −0.29, p < 0.01, for intercept and slope, respectively. This suggests that, similar to relational victimization, levels of internalizing problems decreased over time (Fig. 1). A follow-up analysis indicated that the fit of this second model remained adequate, χ2 (20) = 24.52, p > 0.10, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.04, N = 271. The Chi-square deviance test indeed confirmed a non-significant change, χ2∆ (10) = 7.19, p > 0.50. Thus, the trajectories of internalizing problems did not differ between boys and girls.

Random-Intercept Cross-Lagged Panel Model (RI-CLPM)

Relational Victimization

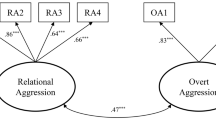

The model for relational victimization and internalizing problems showed a good fit, χ2 (23) = 56.00, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.04, N = 271 (Fig. 2). The random intercept with strong factor loadings (βs = 0.62–0.69) or between-person correlation between relational victimization and internalizing problems was significant, and its effect size was robust (β = 0.52, p < 0.001). After accounting for random intercepts, the within-person stability or autoregressive effects of relational victimization were mostly significant (i.e., they were found to be low to moderate, βs = 0.19–0.29). Interestingly, the within-person stability or autoregressive effects of internalizing problems were significant only between Time 4 and Time 5 (Grade 8). The within-person correlations between relational victimization and internalizing problems were significant across time points, and the effect sizes were also moderate (βs = 0.22–0.41). In terms of within-person change, relational victimization at Time 3 predicted increased internalizing problems at Time 4 (β = 0.28, p < 0.01), which in turn predicted increased relational victimization at Time 5 (β = 0.25, p < 0.05). However, these effects were time-specific, as they only occurred between Time 3 and Time 5. To further examine whether the RI-CLPM of relational victimization differed between boys and girls, a multi-group analysis was conducted. This model fit the data well, χ2 (42) = 68.93, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05, N = 271. The Chi-square deviance test confirmed that there was no significant decrease in the model fit, χ2∆ (19) = 12.93, p > 0.75. This suggests no gender differences in this model.

Overt Victimization

The model for overt victimization and internalizing problems showed a good fit, χ2 (23) = 50.33, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.93, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05, N = 271 (Fig. 3). The random intercept with strong factor loadings (βs = 0.53–0.58) or between-person correlation between overt victimization and internalizing problems was significant (β = 0.32, p < 0.001). After controlling for the random intercept, the within-person stability of overt victimization was found to be small to moderate (βs = 0.05–0.31). The within-person correlation between overt victimization and internalizing problems was not consistently significant; that is, it was significant at Time 4 (β = 0.33, p < 0.001), but not at other times. Unexpectedly, internalizing problems at Time 1 predicted decreases in overt victimization at Time 2 (β = −0.18, p < 0.05); however, none of the other cross-pathways were significant. In addition, a multi-group analysis indicated that the second model fit the data well, χ2 (42) = 64.44, p < 0.05, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.06, N = 271. The Chi-square deviance test verified that there was no significant change in the model fit, χ2∆ (19) = 14.11, p > 0.75, indicating no gender differences in this model.

Discussion

The present study examined developmental changes in forms of peer victimization and internalizing problems and the transactional relations between forms of peer victimization and internalizing problems among Japanese adolescents. Results of GCMs indicated that levels of relational victimization and internalizing problems decreased steadily over time. Overt victimization decreased rapidly and remained relatively constant after this change. The results of the RI-CLPMs further indicated that the random intercepts or between-person correlations between forms of peer victimization and internalizing problems were significant, with a stronger effect size found for relational victimization. The within-person stability and within-person correlations between relational victimization and internalizing problems were more robust and consistent than those for overt victimization. Within-person relational victimization was not longitudinally (across some time periods) associated with internalizing problems, with some exceptions. Relational victimization at Time 3 predicted increases in internalizing problems at Time 4, which in turn led to increases in relational victimization at Time 5. No gender differences were found in the above trajectories and in the transactional models.

Developmental Changes

The developmental changes observed in the present study are largely consistent with a review by Meeus (2016). Meeus (2016) discussed that as children and adolescents grow older, they show substantial positive changes in their social, cognitive, and behavioral development. According to Meeus (2016), these changes are normative and occur in part due to maturation. Adolescents typically develop their personalities and solidify their sense of self and identity, and are therefore more likely to picture who they are compared to younger children. They also tend to think more consciously about their peers and make an effort to interact harmoniously with them. These cognitive and social changes may lead to a decrease in behavioral problems, such as aggression and victimization (Meeus, 2016). Interestingly, however, Meeus’ review states that the majority of studies in this area have shown that social anxiety and depressive symptoms increase from adolescence to adulthood. This latter finding differs from the results of the present study.

These changes may be plausible given the many changes that students face as they transition from elementary to middle school in Japan. When students first enter middle school, they are still adjusting to a different school lifestyle, which is typically referred to as the “intense years” in the Japanese school system (Le Tendre & Fukuzawa, 2001). Students in Japanese middle schools are expected to follow strict rules and obligations while coping with academic pressure from their parents and teachers. Thus, stress may increase with the biological, cognitive, and social changes of puberty. Peer groups are also changing dynamically and expanding into other social contexts, such as after-school academic or sports clubs or juku (private schools that are advanced or complementary to regular public schools). There, students may need to form new peer relationships or restructure them to better fit into their niche peer group. Students facing these challenges may be very anxious about their future school life (Le Tendre & Fukuzawa, 2001). However, as the school year progresses, they may gradually build stable peer relationships (Meeus, 2016) and focus more on academic life. For example, they usually begin to think seriously about getting better grades and letters of recommendation to prepare for high school entrance exams toward graduation while adjusting to the school environment.

The Associations between Relational and Overt Victimization and Internalizing Problems

Although levels of relational victimization decreased over time, they remained detrimental to internalizing problems across five time points. The random intercept of relational victimization was positively correlated with that of internalizing problems, and the effect size was relatively strong. That is, relational victimization was associated with higher levels of internalizing problems at all time points. This finding is consistent with previous research showing a similar pattern (Casper & Card 2017). In a large cross-sectional study of Japanese students in grades 4–9, Murayama et al. (2015) also reported that children who were victims of bullying, primarily relational victimization, were more depressed and at higher risk for self-harm than children who did not experience such victimization. The current study extended previous findings by demonstrating that the negative correlates of relational victimization persisted across three school years.

Results from the RI-CLPM also provided specific information about the stability or stable characteristics of relational victimization and internalizing problems and within-person change in these factors. Specifically, the within-person stability of relational victimization was found to be significant even after the effect of the random intercept (between-person change) was partitioned. This finding suggests that, relative to their own experiences, adolescents who experienced relational victimization were more likely to experience relational victimization at the next time point. However, internalizing problems did not become stable until the end of middle school. The lack of autoregressive effects suggests that middle school students in Japan tended to fluctuate in their levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms, and social withdrawal until they reached 9th grade. Alternatively, the lack of stability in internalizing problems may be partly due to the fact that the random intercept has already been partitioned. Highly depressed adolescents may continue to show high levels of depressive symptoms, perhaps because they have high levels of depressive symptoms to begin with.

Most of the within-person changes between relational victimization and internalizing problems were null. However, some associations were still found to be significant, such that within-person relational victimization, but not within-person overt victimization, predicted relative increases in within-person internalizing problems between Time 3 and Time 4, which in turn predicted relational victimization at Time 5. The sequence of paths from relational victimization to internalizing problems to relational victimization supports the view that relational victimization predicts future relational victimization, in part, through increases in internalizing problems. Specifically, students who experience relational victimization, but not overt victimization may show increased social anxiety, depressive symptoms, and withdrawal, and these inhibited behaviors may lead to later relational victimization. These findings are consistent with prior research. One possible explanation for these time-dependent findings is a lack of within-person stability in internalizing problems between Time 3 and Time 4 and in relational victimization between Time 4 and Time 5. This lack of stability suggests that there is within-person variation in these variables even after the random intercept portion is removed, which may leave some room for the change found in the study. It should be noted, however, that these views are speculative and should be confirmed in a future study.

It is also noted that the random intercept for overt victimization was significant, although its effect size was relatively small to moderate. In other words, overt victimization was positively correlated with internalizing problems at the between-person level. This is consistent with the findings of some studies showing that both overt and relational victimization independently and uniquely predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms in an American youth sample (Williford et al., 2019). However, within-person overt victimization, which splits the variance from the random intercept, was not associated with internalizing problems except at one time interval. The lack of consistent within-person associations for overt victimization mirrors the finding of the meta-analytic study showing that relational victimization, but not overt victimization, was more strongly associated with internalizing problems (Casper & Card, 2017). Given the group orientation of Japanese culture and the relational interdependence of Japanese youth, it is conceivable that both forms of peer victimization, but particularly relational victimization, may be detrimental to internalizing problems.

Gender Differences

We also examined gender differences in developmental change and transactional models. The results of the present study showed no gender differences in any of the analyses. These findings contrast with previous Western studies that found gender differences in relational victimization and internalizing problems (Rose & Rudolph 2006). Specifically, Rose and Rudolph (2006) discussed gender differences in peer relationship styles, stress exposure and response, and relationship provisioning. In terms of relationship style, compared to boys, girls share more concern for, awareness of, and investment in their relationship. While girls tend to be more sensitive to relationships, they are also more exposed to and responsive to interpersonal stress, which may exacerbate the levels of stress resulting from their negative peer experiences (e.g., relational aggression and victimization). It is possible that potential gender differences in the aforementioned relational styles, responses, and coping may be confounded by the cultural orientation of Japanese children. Specifically, it is believed that Japanese children, regardless of gender, are typically concerned with interpersonal relationships due to their high relational interdependence (Kawabata 2018). This strong focus on relational interdependence may minimize gender differences in the ways in how children receive forms of peer victimization and how they respond to such peer adversity (i.e., exhibit internalizing problems).

Limitations

Although the sample size was adequate, the results may not be generalizable or applicable to all Japanese adolescents. There may be within-cultural or regional differences in patterns of relational victimization and social-psychological adjustment. The present study used self-report questionnaires, which may result in shared method variance or self-report bias. Because multiple changes, including biological and social changes, occur during adolescence, the lack of assessment of variables that reflect such changes limits the understanding of relational victimization and its correlates and consequences. For example, stress-related biological factors (e.g., pubertal timing, cortisol) could be considered in future research. Finally, although the present study is longitudinal, it is still correlational. Because correlation does not imply causation, there is no way to interpret the present findings as causal relationships.

Clinical and Educational Implications

The findings regarding the robust associations between relational victimization and internalizing problems suggest the need to find a way to reduce such victimization. One way to reduce peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, is to change the nature of Japanese classrooms. In the current Japanese education system, middle school students rarely move from one classroom to another during the school year and thus spend most of their schooling with the same classmates for at least a year. Due to the closed nature of the classroom, students may have to stay in the same peer group regardless of their wishes, and it may be difficult for them to change peer groups even if they experience relational victimization by their peers. To prevent victims of relational aggression from isolating themselves in the classroom, it may be effective to increase students’ access to other peers. It is important for teachers and school personnel to consider creating frequent opportunities for students to interact with classmates outside of their own peer group by incorporating group activities with different members during class. Observing students from multiple perspectives, including outside volunteers, can also be effective in identifying relational victimization, which is difficult for teachers to observe due to its subtle and indirect nature. Using information from multiple informants, including community members, teachers, and school counselors, we may be able to identify relational victimization early and prevent youth from developing mental health problems.

Data Availability

Data are available upon request.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (2019). International findings with the Achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA): Applications to clinical services, research, and training. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-019-0291-2

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-age Forms & Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

Calhoun, C. D., Helms, S. W., Heilbron, N., Rudolph, K. D., Hastings, P. D., & Prinstein, M. J. (2014). Relational victimization, friendship, and adolescents’ hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis responses to an in vivo social stressor. Development and Psychopathology, 26(3), 605–618. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000261

Casper, D. M., & Card, N. A. (2017). Overt and relational victimization: A meta-analytic review of their overlap and associations with social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 88(2), 466–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12621

Causadias, J. M. (2013). A roadmap for the integration of culture into developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4), 1375–1398. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000679

Cho, D., Zatto, B. R. L., & Hoglund, W. L. G. (2022). Forms of peer victimization in adolescence: Covariation with symptoms of depression. Developmental Psychology, 58(2), 392–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001300

Christina, S., Magson, N. R., Kakar, V., & Rapee, R. M. (2021). The bidirectional relationships between peer victimization and internalizing problems in school-aged children: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 85, 101979. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101979

Cohen, J. (2016). A power primer. In A. E. Kazdin (Ed.), Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research (pp. 279–284). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14805-018

Crick, N. R., & Bigbee, M. A. (1998). Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multiinformant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66(2), 337–347. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.66.2.337

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1996). Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 8(2), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400007148

Davies, R. J., & Ikeno, O. (2002). The Japanese mind: Understanding contemporary Japanese culture. Tuttle Pub.

Farrell, A. D., Goncy, E. A., Sullivan, T. N., & Thompson, E. L. (2018). Victimization, aggression, and other problem behaviors: Trajectories of change within and across middle school grades. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(2), 438–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12346

Fite, P. J., Gabrielli, J., Cooley, J. L., Rubens, S. L., Pederson, C. A., & Vernberg, E. M. (2016). Associations between physical and relational forms of peer aggression and victimization and risk for substance use among elementary school-age youths. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 25(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/1067828X.2013.872589

Funabiki, Y., & Murai, T. (2017). Standardization of a Japanese version of the youth self-report for school ages 11-18. Japanese journal of child and adolescent. Psychiatry, 58(5), 730–741. https://doi.org/10.20615/jscap.58.5_730

Giesbrecht, G. F., Leadbeater, B. J., & MacDonald, S. W. (2011). Child and context characteristics in trajectories of physical and relational victimization among early elementary school children. Development and Psychopathology, 23(1), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000763

Hamamura, T. (2012). Are cultures becoming individualistic? A cross-temporal comparison of individualism–collectivism in the United States and Japan. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311411587

Hankin, B. L., Stone, L., & Wright, P. A. (2010). Corumination, interpersonal stress generation, and internalizing symptoms: Accumulating effects and transactional influences in a multiwave study of adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 217–235. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990368

Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Kawabata, Y. (2018). Cultural contexts of relational aggression. In S. M. Coyne & J. M. Ostrov (Eds.), The development of relational aggression (pp. 265–280). Oxford University Press.

Kawabata, Y. (2020). Measurement of peer and friend relational and physical victimization among early adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 82(1), 82–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.05.004

Kawabata, Y., Crick, N. R., & Hamaguchi, Y. (2010). Forms of aggression, social-psychological adjustment, and peer victimization in a Japanese sample: The moderating role of positive and negative friendship quality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(4), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9386-1

Kawabata, Y., Tseng, W. L., & Crick, N. R. (2014). Mechanisms and processes of relational and physical victimization, depressive symptoms, and children's relational-interdependent self-construals: Implications for peer relationships and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 26(3), 619–634. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579414000273

Le Tendre, G. K., & Fukuzawa, R. E. (2001). Intense years: How Japanese adolescents balance school, family and friends. Routledge.

Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

Marsh, H. W., Craven, R. G., Parker, P. D., Parada, R. H., Guo, J., Dicke, T., & Abduljabbar, A. S. (2016). Temporal ordering effects of adolescent depression, relational aggression, and victimization over six waves: Fully latent reciprocal effects models. Developmental Psychology, 52(12), 1994. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000241

Meeus, W. (2016). Adolescent psychosocial development: A review of longitudinal models and research. Developmental Psychology, 52(12), 1969–1993. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000243

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2020). Considering social security and work styles in Reiwa [White paper]. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000735866.pdf

Murayama, Y., Ito, H., Hamada, M., Nakajima, S., Noda, W., Katagiri, M., Takayanagi, N., Tanaka, Y., & Tsujii, M. (2015). Relationships of bullying behaviors and peer victimization with internalizing/externalizing problems. The Japanese Journal of Developmental Psychology, 26, 13–22.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (1998-2017). Mplus User’s Guide. Muthén & Muthén.

Orpinas, P., McNicholas, C., & Nahapetyan, L. (2015). Gender differences in trajectories of relational aggression perpetration and victimization from middle to high school. Aggressive Behavior, 41(5), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21563

Ostrov, J. M., & Godleski, S. A. (2013). Relational aggression, victimization, and adjustment during middle childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 25(3), 801–815. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000187

Ostrov, J. M., & Kamper, K. E. (2015). Future directions for research on the development of relational and physical peer victimization. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44(3), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1012723

Osuka, Y., Nishimura, T., Wakuta, M., Takei, N., & Tsuchiya, K. J. (2019). Reliability and validity of the Japan Ijime scale and estimated prevalence of bullying among fourth through ninth graders: A large-scale school-based survey. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 73(9), 551–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12864

Pagliaccio, D., Kumar, P., Kamath, R. A., Pizzagalli, D. A., & Auerbach, R. P. (2023). Neural sensitivity to peer feedback and depression symptoms in adolescents: A 2-year multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 64(2), 254–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13690

Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2010). Active defending and passive bystanding behavior in bullying: The role of personal characteristics and perceived peer pressure. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(6), 815–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9399-9

Prinstein, M. J., & Giletta, M. (2020). Future directions in peer relations research. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 49(4), 556–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1756299

Prinstein, M. J., Boergers, J., & Vernberg, E. M. (2001). Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social–psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 30(4), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98

Rudolph, K. D., Flynn, M., & Abaied, J. L. (2008). A developmental perspective on interpersonal theories of youth depression. In J. R. Z. Abela & B. L. Hankin (Eds.), Handbook of depression in children and adolescents (pp. 79–102). The Guilford Press.

Sentse, M., Prinzie, P., & Salmivalli, C. (2017). Testing the direction of longitudinal paths between victimization, peer rejection, and different types of internalizing problems in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45(5), 1013–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0216-y

Smetana, J. G., Robinson, J., & Rote, W. M. (2015). Socialization in adolescence. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 60–84). The Guilford Press.

Syed, M., & Kathawalla, U. K. (2022). Cultural psychology, diversity, and representation in open science. In K. C. McLean (Ed.), Cultural methods in psychology: Describing and transforming cultures (pp. 427–454). Oxford University Press.

Tampke, E. C., Blossom, J. B., & Fite, P. J. (2019). The role of sleep quality in associations between peer victimization and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 41, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9700-8

Toda, Y. (2016). Bullying (Ijime) and related problems in Japan: History and research. In P. K. Smith, K. Kwak, & Y. Toda (Eds.), School bullying in different cultures: Eastern and Western perspectives (pp. 73–92). Cambridge University Press.

Tran, C. V., Cole, D. A., & Weiss, B. (2012). Testing reciprocal longitudinal relations between peer victimization and depressive symptoms in young adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41(3), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.662674

Umezu, N., Arai, K., & Hamaguchi, Y. (2012). The relationships between relational aggression, cognitive characteristics and adjustment in Japanese junior-high school students: Focusing on hostile attribution. Tsukuba Psychological Research, 44, 69–78.

Will, G. J., van Lier, P. A., Crone, E. A., & Güroğlu, B. (2016). Chronic childhood peer rejection is associated with heightened neural responses to social exclusion during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-9983-0

Williford, A., Fite, P. J., Isen, D., & Poquiz, J. (2019). Associations between peer victimization and school climate: The impact of form and the moderating role of gender. Psychology in the Schools, 56(8), 1301–1317. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22278

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the present study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (16 K17323).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by Konan University’s Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent

Informed consent or assent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Parental consent was sought under the guidance of schools. Consent from school principals was also obtained. This procedure was approved by the authors’ IRB.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

Figure S1, S2 and Table S1 (DOCX 290 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawabata, Y., Kinoshita, M. & Onishi, A. A Longitudinal Study of Forms of Peer Victimization and Internalizing Problems in Adolescence. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol 52, 983–996 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-023-01155-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-023-01155-9