Abstract

Theory suggests that aversive social experiences generate emotional maladjustment because they prompt the development of a hypersensitivity to perceiving and overreacting to rejection. The primary aim of this study was to test hypothesized direct and indirect (via rejection sensitivity) links of overt/relational victimization and friendship conflict with early adolescents’ loneliness and depressive symptoms. Participants were 366 Australian early adolescents age 10–14 years (50.5 % girls). Using both a self-report and peer-report measure of rejection sensitivity, no difference was found when comparing the significant correlations of each measure with loneliness and depressive symptoms. Tests of direct and indirect associations with structural equation modeling showed that adolescents higher in relational victimization reported more loneliness and depressive symptoms and part of this association was by way of their greater self-reports of rejection sensitivity and their peers’ identification that they were higher in rejection sensitivity. Additionally, relational victimization was the only unique correlate of emotional maladjustment, and adolescents who reported more overt victimization were identified by their peers as higher in rejection sensitivity. Finally, gender and rejection sensitivity were tested as moderators. No gender moderation was found, but friendship conflict was associated more strongly with emotional maladjustment for adolescents low, rather than high, in rejection sensitivity. These findings identify relational victimization as particularly salient for emotional maladjustment both directly and indirectly via links with elevated rejection sensitivity. They show how rejection sensitivity and aversive experiences may contribute independently and jointly to emotional maladjustment for both boys and girls.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescents’ aversive experiences with classmates and friends, such as rejection and conflict, have unique roles in predicting emotional maladjustment (London et al. 2007; McDonald et al. 2010). Moreover, rejection sensitivity, defined as the tendency to anxiously or angrily expect, readily perceive and overreact to rejection can develop following aversive social experiences (Chango et al. 2012; Downey et al. 1998). Various cognitive models argue that rejection sensitivity and similar sociocognitive processing biases can help to explain why some children and adolescents exhibit more maladaptive responses to aversive social experiences and develop signs and symptoms of negative social and emotional adjustment (Abela and Hankin 2009; Downey et al. 1999). Thus, rejection sensitivity may be a mechanism that can account for why aversive social experiences coalesce in emotional maladjustment. The general aim of the present study was to test this rejection sensitivity model focusing only on early adolescents. We extend existing research by measuring rejection sensitivity with both the usual self-report measure and a new peer-report measure. This allowed us to examine associations of multiple forms of peer relationship problems with early adolescents’ emotional adjustment via both self-reported and peer-reported rejection sensitivity, while also focusing on gender moderation. Finally, we also examined whether rejection sensitivity may exacerbate the correlational effect of aversive peer experiences on early adolescents’ emotional maladjustment.

Peer-Reported Rejection Sensitivity

The first extension on previous research was the development and use of a new measure of rejection sensitivity based on peer reports. This allowed for tests of self-reported and peer-reported rejection sensitivity as mediators of associations between aversive peer experiences, on the one hand, and loneliness and depressive symptoms on the other hand. All of what currently is known about the role of rejection sensitivity in adolescents’ socioemotional maladjustment is based on self-reports of both the tendency to perceive and overreact to rejection, as well as self-reports of emotional and social problems. It follows that research efforts could be enhanced if multiple informants provide reports of rejection sensitivity. For example, this might reduce concerns about using self-reports when there is the possibility of enhanced recall of rejection (London et al. 2007) or overestimation of rejection (Zimmer-Gembeck et al. under review) among individuals higher in rejection sensitivity.

Students have been found to provide valid reports of many behavioral and emotional aspects of their peers at school (Swenson and Rose 2009; Weiss et al. 2002). In particular, students have been found to be good informants about emotional states, such as depressive symptoms, showing significant accuracy in their reports when contrasted with self-reports (Swenson and Rose 2009). It appears that young people are good observers of their peers’ behaviors, such as witnessing and reporting about withdrawing, being wary or displaying negative affect more often than others (Rubin et al. 2006), and they talk with their friends and other peers about feelings (Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011). They seem able to rely on these observations and interactions to make judgements about depressive or other symptoms. We expected that adolescents would also be good observers of behaviors that indicate rejection sensitivity, such as overreacting in social situations, and reacting with anxiety and anger quickly or excessively when there is a rejection threat or when actual rejection occurs. We expected also that collecting such information from a range of their peers would enhance accuracy because students often spend years having contact with the same agemates at their school, and they often spend a great deal of time together and talk frequently about both their friends and others in their wider peer networks (Adler and Adler1998; Pronk and Zimmer-Gembeck 2010). On this basis, researchers have recommended using both self and peer reports of important variables in studies of peer relationships and mental health (Nuijens et al. 2009; Swenson and Rose 2009).

Loneliness and Depressive Symptoms: Links to Aversive Peer Experiences

This study’s second extension on prior research was the testing of a path model to examine multiple measures of aversive peer experiences as correlates of rejection sensitivity at the same time as examining associations of rejection sensitivity with two aspects of emotional maladjustment, namely loneliness and depressive symptoms. Almost all of the past research on peer relationships, rejection sensitivity and emotional adjustment has focused only on dislike (rejection) by peers. In the present study, aversive peer social experiences included overt/physical-verbal victimization, relational victimization and friendship conflict. Hence, past research was extended by focusing on a range of important aversive peer social experiences as correlates of adolescents’ emotional maladjustment.

Aversive Peer Experiences and Emotional Adjustment

Overt and relational victimization were important to consider as correlates of socioemotional adjustment. Overt victimization involves harm through physical aggression, verbal threats or intimidation, whereas relational victimization refers to the experience of harm through damage and manipulation of peer relationships (e.g., spreading rumours and social exclusion; Crick and Grotpeter 1995). Peer victimization has been supported as a correlate and as an antecedent of loneliness and depression (Card and Hodges 2008; Woodhouse et al. 2012). However, recent research incorporating measures of both overt and relational victimization tends to show that relational victimization is more strongly associated with depressive symptoms and other socioemotional adjustment problems than overt victimization during late childhood and early adolescence, with findings emerging from the USA, Canada and China (Cole et al. 2010; Pepler et al. 2006; Sinclair et al. 2012; Yoshito et al. 2012). Hence, in the present study, we anticipated that relational victimization would be associated more strongly with depressive symptoms and loneliness than overt victimization. Although no previous research has examined overt and relational victimization as correlates of early adolescents’ rejection sensitivity, we also anticipated that relational victimization, in contrast to overt victimization, would have a stronger association with rejection sensitivity given the known associations of rejection sensitivity with depressive symptoms and loneliness.

In addition to victimization, we also considered friendship conflict. Conflict has been argued to be one aspect of friendship that is particularly important to examine when accounting for loneliness and depressive symptoms among adolescents (Rubin et al. 2006). In one study, even after accounting for other aspects of peer relationships, unique associations were reported between child and adolescent low friendship quality and greater loneliness and depressive symptoms (Nangle et al. 2003). Based on these previous findings, we expected that friendship conflict would have unique associations with rejection sensitivity, depressive symptoms, and loneliness after accounting for victimization.

Rejection Sensitivity as a Mediator

Rejection sensitivity has been described as a system of processing social information that develops from negative relational experiences and guides responses to current and future situations (Downey and Feldman 1996). For example, when negative social experiences occur, such as rejection or victimization, the course of development will include more negative views of relationships and greater expectations that others will not be accepting or will be rejecting (Downey et al. 1999; Downey and Feldman 1996). These expectations may create social problems that eventually coalesce as loneliness and depression, given the importance of intimate close relationships and belonging for avoiding these mental health problems (Baumeister and Leary 1995). Hence, theory suggests that rejection sensitivity may be a mediator that can account for why adolescents’ aversive social experiences are associated with socioemotional adjustment problems.

Despite the availability of this rejection sensitivity model, we could locate only six published studies of peer relationships and rejection sensitivity (Butler et al. 2007; Chango et al. 2012; London et al. 2007; McLachlan et al. 2010; Sandstrom et al. 2003; Wang et al. 2012), and not one examined rejection sensitivity as a mediator of associations between aversive peer experiences of victimization and friendship conflict and emotional adjustment outcomes of loneliness and depressive symptoms. Hence, guided by the rejection sensitivity model, we anticipated that early adolescents’ aversive peer experiences of victimization and friendship conflict would covary with elevated rejection sensitivity. In turn, rejection sensitivity, as reported by self and peers, was expected to covary with more emotional maladjustment in the forms of elevated loneliness and depressive symptoms. Associations were expected to be strongest for relational victimization, but we also expected some unique associations of physical victimization and friendship conflict.

Gender Differences

The third extension on previous research was the testing of gender moderation, but it was unclear what differences to anticipate. On the one hand, the mental health consequences of peer rejection and elevated rejection sensitivity have been found for boys and girls (Downey et al. 1998; London et al. 2007), and no significant gender differences have been found in three studies—two studies of early adolescents’ peer rejection, perceived social acceptance and depression (Bauman 2008; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2007) and one study of associations between early adolescents’ peer rejection and rejection sensitivity (McLachlan et al. 2010). However, on the other hand, most past studies of peer relationships, rejection sensitivity and emotional adjustment have focused on peer rejection only. Yet, gender differences in associations may be more likely when the focus is on victimization and friendship conflict. Victimization has been found to differ between boys and girls. Early adolescent boys are more overtly victimized than girls (Cullerton-Sen and Crick 2005). Moreover, some studies have found that early adolescent girls are reported by their peers to inflict slightly more relational victimization than boys (Crick and Grotpeter 1995), while others conclude relational victimization does not differ between adolescent boys and girls (Card et al. 2008).

Regarding friendship, gender differences have been found. In one study, the association between friendship conflict and greater emotional difficulties (e.g., depression, loneliness and helplessness) was stronger for girls than boys (Newman Kingery et al. 2011). Moreover, in theory, friendship is expected to be more strongly associated with girls’ than boys’ well-being (Rose and Rudolph 2006). Hence, there are also reasons to expect gender differences. Yet, overall, given the mixed findings and past evidence, we did not make a priori hypotheses regarding gender moderation of associations between victimization, rejection sensitivity, depressive symptoms, and loneliness. However, we tentatively anticipated that friendship conflict would be associated more strongly with depressive symptoms and loneliness for girls than for boys.

Rejection Sensitivity as a Moderator

The rejection sensitivity model (Chango et al. 2012; Downey et al. 1999) and other theories of the development of emotional problems (e.g., Abela and Hankin 2009) have raised the possibility that particular dispositional traits or states (such as high rejection sensitivity) and negative social experiences (such as a history of less peer acceptance) combine to be particularly problematic for emotional functioning (Chango et al. 2012; McLachlan et al. 2010). Consistent with these views, we tested whether rejection sensitivity would moderate (change) how aversive peer experiences were associated with depressive symptoms and loneliness. It was difficult to predict whether moderation would be found, however, because no previous study has examined rejection sensitivity in interaction with multiple aversive peer experiences as correlates of early adolescents’ depressive symptoms and loneliness. Nevertheless, given the widespread view that emotional problems are outcomes of individual dispositions interacting with social experiences, we expected that rejection sensitivity would moderate the association of aversive peer experiences with depressive symptoms and loneliness, with high rejection sensitivity exacerbating negative outcomes in the face of aversive peer experiences and low rejection sensitivity helping to protect young people from maladjustment outcomes.

Early Adolescents

A final extension on past research was the inclusion of only early adolescents in the present study. We focused on early adolescents for three reasons. First, almost all other studies have examined older adolescents’ peer relationships, rejection sensitivity and emotional adjustment exclusively or in combination with early adolescents. It is important for research to focus on early adolescents because overt, as well as relational, types of victimization during adolescence are prevalent and painful forms of rejection by peers, and are especially prevalent in early adolescence (Cross et al. 2009; Pellegrini and Long 2002). Second, peer group relationships and friendships become more prominent sources of support and social acceptance beginning in early adolescence (Rose and Rudolph 2006; Rubin et al. 2006). Likewise, victimization by peers and conflict with friends are common and particularly potent negative experiences for early adolescents. Finally, a third reason for the exclusive focus on early adolescents was the significant changes in cognitions about the self and others at this time of life. Such changes include the development of more complex conceptions of the self, which can be positive or negative and begin to stabilize (Harter 2012), which may be linked to rejection sensitivity and may be one reason that depressive symptoms escalate and become more stable into adolescence (Nolen-Hoeksema 2001; Sinclair et al. 2012). Early adolescence is clearly a distinct and important age period to examine peer relationships, rejection sensitivity, and emotional maladjustment.

Study Objectives and Hypotheses

In the present study, we examined if self-reported and a new peer-report measure of rejection sensitivity were each associated with aversive peer experiences and depressive symptoms and loneliness, and determined whether rejection sensitivity reported by peers had unique associations after considering self-reported rejection sensitivity. We expected that the associations between aversive peer social experiences and mental health outcomes would be partly indirect with rejection sensitivity (reported by self and peers) as an intermediary, as has been proposed in the rejection sensitivity model (Downey et al. 1999; London et al. 2007). Moreover, we expected that relational victimization, compared to overt victimization, would have stronger associations with rejection sensitivity and socioemotional adjustment, but that each of relational victimization, overt victimization and friendship conflict would play a unique role in rejection sensitivity and socioemotional adjustment. Because mediation (i.e., indirect associations) and moderation are two important processes that might explain how rejection sensitivity plays a role in the associations between peer relationship problems and adolescents’ emotional adjustment, we also tested rejection sensitivity as a moderator. In these analyses, we expected that high rejection sensitivity would enhance the impact of aversive peer social experiences on maladjustment and low rejection sensitivity would protect against maladjustment in the face of aversive social experiences. Further, gender differences in associations (i.e., gender moderation) were tested between aversive peer social experiences, rejection sensitivity, loneliness, and depressive symptoms. We expected friendship conflict to have stronger implication for girls’ rejection sensitivity and socioemotional adjustment than for boys’ rejection sensitivity and adjustment, but did not make a priori hypotheses about other associations.

Method

Participants

The participants were 366 early adolescents (age 10–14, M = 12.1 years, SD = 1.0 year) from two schools in an urban area of Australia. Overall, there were 181 boys (49.5 %) and 185 girls (50.5 %) who participated. They were in grades six (n = 129), seven (n = 125) or eight (n = 112). Both schools contained students from the low-middle to the high-middle range of socioeconomic status, and ethnicity represented the region from which the schools were selected, with approximately 90 % white/Australian or New Zealander, and 10 % Asian, Aboriginal Australian, Maori, Middle Eastern or from other sociocultural backgrounds. Participation in the study required parental consent and adolescent assent. The parental consent rate was 73 %, with most of the nonparticipants simply failing to return consent forms.

Measures

Loneliness

The Loneliness and Social Dissatisfaction Questionnaire (LSDQ; Cassidy and Asher 1992) was employed to measure loneliness. The 13 self-report items had response options ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 5 (very true). A sample item reads, “I feel alone”. Of the 13 items in the LSDQ, nine positively worded items were reversed to maintain consistent direction of responses. Averaging all responses created a total loneliness score, such that higher scores indicated higher levels of loneliness. Cronbach’s α for the current study was .91.

Depressive Symptoms

The short form (10 items) of the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) was used to assess depressive symptoms (Kovacs 1985). Participants selected one of three statements, graded in severity, that best described how they had been feeling and thinking over the preceding 2 weeks. Responses to five items were reversed to maintain scoring consistency. Participant responses to all items were averaged to provide a total score, with higher scores reflecting greater severity of depressive symptoms, Cronbach’s α = .80.

Rejection Sensitivity Self-Reports

Six items from the Children’s Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (CRSQ; Downey et al. 1998) measured anxious expectations of rejection. The CRSQ included written vignettes that implied the possibility of not being accepted or being overtly rejected. Vignettes involved teachers (3 vignettes) or peers (3 vignettes). Two responses to each vignette were used in this study to gauge children’s anxious expectations of rejection. An example reads, “Imagine that a famous person is coming to visit your school. Your teacher is going to pick five kids to meet this person. You wonder if she will choose YOU”. The first question assessed anxious responses by asking how nervous they would feel if they were in this situation. Responses to this item ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (yes/extremely). The second question assessed perception of the likelihood of an accepting versus rejecting response from the others portrayed in the vignettes. An example reads, “Do you think the teacher will choose YOU?”. Responses were 1 (NO!), 2(no, I don’t think so), 3 (maybe), 4 (yes, probably), and 5 (YES!). To calculate total rejection sensitivity scores, the response to the anxious item was multiplied by the response to the reversed expectation item. Averaging these scores across the six vignettes produced a single, total rejection sensitivity score. Higher scores represented greater levels of rejection sensitivity, Cronbach’s α was .79.

Rejection Sensitivity Peer-Report

For the current study a new scale was devised to measure rejection sensitivity in adolescents as reported by their peers. Based on rejection sensitivity theory and the definition of rejection sensitivity, scale items were created to measure what was likely to be observed in a child high in rejection sensitivity. Items were worded to focus on anxiety about rejection, expectation of rejection and overreaction to rejection. Six experts reviewed, discussed and modified the scale items. The items were piloted with five children in the age range of the research participants to ensure they were readable, comprehensible and within the age group ability level. The final scale comprised six items (see “Appendix”).

Students nominated up to three classmates for each rejection sensitivity item. Nominations received were summed for each participant, and totals for each item were standardized within classroom following procedures used for peer nominations developed in past research (Coie et al. 1982; Crick 1996). This resulted in six item scores that could be subjected to factor analysis to examine whether all items loaded on a single factor. Prior to conducting principle axis factoring, assumptions of this analysis were first investigated. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO) for the overall sample was good (.87). Bartlett’s test of Sphericity was significant, χ2(15) = 1,307.6, p < .001, providing evidence for an acceptable number of significant correlations between variables. A clear 1-factor solution was extracted that had a large eigenvalue of 4.0, with all other eigenvalues less than 1.0. Each of the six items had high factor loadings ranging from .67 to .85, with all but two loadings at .80 or higher. The six items accounted for 67 % of the variance in the factor. Hence, a total score for peer-reported rejection sensitivity was calculated by averaging the six item scores. Higher scores indicated more rejection sensitivity. Cronbach’s α was .90.

Peer Victimization

The Children’s Social Behavior Scale (Crick and Grotpeter 1995) was used to assess overt (3 items) and relational victimization (4 items). Overt victimization included harm through physical aggression, verbal threats or instrumental intimidation. Relational victimization included harm through damage and manipulation of peer relationships. An example of an overt victimization item was, “Kids threaten to or do push, shove or hit me”. An example of a relational victimization item was, “Kids leave me out on purpose”. Responses for each item ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). In the current study, total scores for overt victimisation and relational victimisation were calculated by averaging responses to each item, such that higher scores indicated greater victimization. In the current study, Cronbach’s α for the overt victimization items was .84 and Cronbach’s α was .75 for the relational victimization items.

Friendship Conflict

The 3-item conflict subscale from the Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI; Furman and Buhrmester 1985) was used to assess each child’s conflict with his or her very best friend. Responses for the three items ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a lot). An example item was, “How much do you and your friend disagree or argue with each other?”. Averaging the items formed a total conflict score, such that a higher score indicated greater friendship conflict, Cronbach’s α = .82.

Procedure

Approvals from the Human Subjects Review Committee of the University and the appropriate school administration bodies were attained prior to the commencement of the current study. Schools were visited to distribute parent information sheets and assent forms to students. Students took the forms home to their parents and returned them to the school on completion. Children with parental consent who also assented to participate were given questionnaire booklets during regular class hours within their normal classrooms. Questionnaires were completed in two sessions held 2 weeks apart to reduce student fatigue. Students without consent completed an alternate task. It took approximately 20 min for students to complete the items used in this study. Students were given the opportunity to debrief with a psychologist.

Results

Association Between Rejection Sensitivity Self-Reports and Rejection Sensitivity Peer-Reports

Correlations between all variables are shown in Table 1. Providing some support for the validity of the peer-report rejection sensitivity measure, there was a positive correlation between rejection sensitivity self-reports and rejection sensitivity peer reports, r = .26, p < .01. However, this effect size was quite modest, as has been found for reports from different respondents in past research measuring peer rejection (e.g., about .40 or less; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2007).

When the associations of rejection sensitivity self-reports and rejection sensitivity peer-reports with loneliness and depressive symptoms were compared, there were no significant differences. The association between rejection sensitivity self-reports and loneliness, r = .42, and rejection sensitivity peer-reports and loneliness, r = .43, did not differ, t = −0.18, p = .57. Also, no difference was found for the association between rejection sensitivity self-reports and depressive symptoms, r = .37, when compared to rejection sensitivity peer-reports and depressive symptoms, r = .29, t = 1.36, p = .09. Hence, although the association between rejection sensitivity self-reports and rejection sensitivity peer-reports was only modest, each measure had quite similar associations with loneliness and depressive symptoms.

Rejection sensitivity self-reports and peer-reports had similar correlations with relational victimization, t = −0.70, p = .48, and with friendship conflict, t = −0.16, p = .87. The positive association of rejection sensitivity peer-reports and overt victimization, r = .40, p < .01, was stronger than between rejection sensitivity self-reports and overt victimization, r = .22, p < .01, t = 3.05, p < .01.

Gender Differences

Means and standard deviations for all measures and comparisons of boys and girls are also shown in Table 1. Boys reported more overt victimization and friendship conflict than girls, but boys’ and girls’ reports of relational victimization did not differ. For rejection sensitivity, there was no gender difference in peer reports of rejection sensitivity, but girls self-reported more rejection sensitivity than boys. Loneliness and depressive symptoms did not differ between boys and girls.

Multivariate Associations

SEM was used to test the direct effects of peer aversive experience on rejection sensitivity and socioemotional adjustment (loneliness and depressive symptom) and to examine the indirect effects of peer aversive experience on adjustment via rejection sensitivity by adding paths from rejection sensitivity to depressive symptom and loneliness in a second model. Models were estimated using AMOS software with maximum likelihood estimation (IBM Corporation). Model fit was assessed with commonly used indices, including the χ2-test and associated level of significance, and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (Bentler and Bonett 1980). The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) (Browne and Cudeck 1993) provided an estimate of error due to approximate fit of the models.

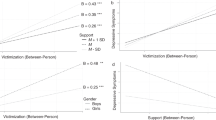

In these models, effects of friendship conflict on rejection sensitivity were not freed given that there were no significant bivariate associations. The fit of the first model testing only the direct associations of victimization with rejection sensitivity, and direct associations of victimization and friendship conflict with socioemotional outcomes, was poor, χ2(6) = 66.93, p < .001, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .166 (90 % CI .132–.203), p < .01. The significant paths are shown in Fig. 1. In this model, relational victimization was associated with greater rejection sensitivity (self-reports and peer-reports, .43 and .20, respectively) and worse adjustment (.43 for loneliness and .42 for depressive symptoms). In addition, overt victimization had a unique association with greater rejection sensitivity peer-reports (.27), and friendship conflict had a small but significant association with greater loneliness (.09). When the four paths that were not significant were removed, the fit of the model was similar, χ2(10) = 71.91, p < .001, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .130 (90 % CI .103–.159), p < .01; χ2-difference(4) = 4.98, p > .05.

Results of a structural equation model estimating direct correlational path coefficients from peer aversive experiences to rejection sensitivity and socioemotional adjustment. Note χ2(6) = 66.93, p < .001, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .166 (90 % CI .132–.203), p < .01. All shown paths were significant at p < .01 except where noted with *p < .05. The three other possible paths from overt victimization to other measures and the one other possible path from friendship conflict to depressive symptoms were also freed but are not shown here because they were not significantly different from 0. When these four paths were removed the model fit was χ2(10) = 71.91, p < .001, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .130 (90 % CI .103–.159), p < .01

In Model 2 (see Fig. 2), the freeing of paths from rejection sensitivity to socioemotional adjustment measures improved the fit of the model, χ2(6) = 6.36, p = .38, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .013 (90 % CI .000–.070), p = .80, χ2-difference(4) = 65.55, p < .01. All paths from rejection sensitivity to socioemotional adjustment were significant indicating that the adolescents who self-reported or were reported by their peers as higher in rejection sensitivity also reported greater loneliness and more elevated depressive symptoms. There were some differences, but also some surprising lack of difference, in paths from victimization to rejection sensitivity self-reports compared to rejection sensitivity peer-reports, and from the two measures of rejection sensitivity to socioemotional adjustment outcomes. In particular, the paths from relational victimization to rejection sensitivity self-reports and peer-reports were significant (.41 and .19, respectively), but the former association was stronger than the later. Similar findings emerged for the paths from rejection sensitivity self-reports and rejection sensitivity peer-report to depressive symptoms, with the path from rejection sensitivity self-reports to depressive symptoms (.21) larger than the path from rejection sensitivity peer-reports to depressive symptoms (.09). In contrast, the path from overt victimization to rejection sensitivity self-reports was not significant (−.03) but the path from overt victimization to rejection sensitivity peer-reports was significant (.28). Also, the paths from rejection sensitivity self-reports and rejection sensitivity peer-reports to loneliness did not appear to differ (.23, .24, respectively). Hence, for two measures (relational victimization and depressive symptoms) associations appeared to be stronger with rejection sensitivity self-reports than peer-reports, whereas for two other measures in the model (overt victimization and loneliness) this was not the case. Overall, this model accounted for 18 % of the variance in rejection sensitivity self-reports, 18 % of the variance in rejection sensitivity peer-reports, 38 % of the variance in loneliness, and 29 % of the variance in depressive symptoms.

Results of a structural equation model estimating direct and indirect (via rejection sensitivity) correlational path coefficients from peer aversive experiences to socioemotional adjustment. Note χ2(6) = 6.36, p = .38, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .013 (90 % CI .000–.070), p = .81. All paths were significant at p < .01 except where noted with a p = .07 or ns indicating p > .07

Bootstrapped estimates of the direct, indirect (via rejection sensitivity) and total effects of aversive peer experience on loneliness and depressive symptoms are shown in Table 2. As can be seen, relational victimization had both significant direct and indirect effects on loneliness and depressive symptoms, with large total effects (.45 and .47, respectively) and direct effects about 2–3 times larger than indirect effects. Hence, adolescents’ perception that they were relationally victimized was associated directly with reports of greater loneliness and depressive symptoms, but also victimization, in the forms of ostracism, gossip and exclusion, was associated with greater sensitivity to rejection, which in turn was associated with more loneliness and depressive symptoms. There were no significant direct or indirect effects of overt victimization and friendship conflict on loneliness and depressive symptoms in this model.

Gender Moderation

Two-group (Boy/Girl) models were estimated to examine whether the final model effects differed for boys and girls. The first model constrained all paths to be equal for boys and girls (equality constraint model). In the second model (gender-specific model), we maintained the equality-constrained intercorrelations between peer aversive behaviors, between rejection sensitivity measures, and between loneliness and depressive symptoms, but all hypothesized directional associations were allowed to differ between boys and girls. Both models had a good fit to the data, gender equality constraint model χ2(27) = 37.35, p = .17, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .032 (90 % CI .000–.056), p = .89; gender-specific model χ2(17) = 24.91, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .036 (90 % CI .000–.064), p = .77. Moreover, the fit of these two models did not differ, χ2-difference(10) = 12.4, p > .20. Hence, freeing these 10 pathways to estimate gender-specific coefficients did not significantly improve model fit. This suggests that no path significantly differed between girls and boys, and there was no support for the hypothesis that aversive peer experiences and loneliness would have more effect on girls’ symptoms than on boys’ symptoms.

Rejection Sensitivity as a Moderator

Our final study aim was to examine whether rejection sensitivity was a moderator of the negative associations of aversive peer experiences with depressive symptoms and loneliness. Because this involved testing 12 interactions, we tested each interaction one at a time using the SPSS macro, Process (Hayes 2013). Two of the 12 interactions were significant and both involved friendship conflict. The first significant interaction was between friendship conflict and peer-reports of rejection sensitivity when the dependent variable was depressive symptoms, Β = −.539, p = .013. The second significant interaction was between friendship conflict and self-reports of rejection sensitivity when the dependent variables was loneliness, Β = −.027, p = .006. All other interactions were not significant (p from .073 to .962).

The two significant interactions were explored further by plotting friendship conflict against predicted emotional maladjustment at low, moderate, and high levels of rejection sensitivity (see Figs. 3, 4). As can be seen in these figures, the associations between friendship conflict and depressive symptoms (Fig. 3) and between friendship conflict and loneliness (Fig. 4) were similar in pattern, with each association weaker when rejection sensitivity was high compared to low or moderate. This was primarily because adolescents with high rejection sensitivity were quite high in maladjustment, and their maladjustment was not as strongly associated with their level of friendship conflict. In comparison, friendship conflict was associated more strongly with emotional maladjustment when adolescents were low in rejection sensitivity. Hence, friendship conflict was more relevant for understanding depressive symptoms and loneliness in low and moderate rejection sensitivity adolescents.

Discussion

Aversive social experiences often generate emotional maladjustment among children and adolescents, but research on the identification of the cognitive, emotional or behavioral mechanisms that account for these associations is still in its infancy. The primary aim of this study was to test hypothesized direct and indirect (via rejection sensitivity) links of aversive peer experiences during early adolescence, including overt/relational victimization and friendship conflict, with loneliness and depressive symptoms. Overall, we had four aims in the current study. The first aim was to examine associations between aversive peer experiences (overt victimization, relational victimization and friendship conflict), rejection sensitivity, loneliness, and depressive symptoms. We expected that relational victimization would have the most prominent associations with early adolescents’ loneliness and depressive symptoms. The second study aim was to test a key aspect of rejection sensitivity theory, that there would be indirect associations of aversive peer experiences with depression symptoms and loneliness via rejection sensitivity, which was measured with self-reports and peer-reports (Downey et al. 1999). The third study aim was to investigate whether high rejection sensitivity moderated (i.e., strengthened) associations between aversive peer experiences and emotional maladjustment (depressive symptoms and loneliness). Finally, the fourth aim was to test for gender differences in associations between aversive peer experiences, rejection sensitivity, and emotional maladjustment.

In total, there were six key findings of the present study. First, as anticipated and consistent with previous research on aversive peer experiences and emotional adjustment among adolescents (Card and Hodges 2008; Cross et al. 2009; Zimmer-Gembeck and Pronk 2012), victimization—both overt and relational—and friendship conflict (peer aversive experiences) were associated with greater loneliness and more depressive symptoms when simple associations were examined. Two of the three measures of peer aversive experiences, overt and relational victimization but not friendship conflict, also were associated with both self-reported and peer-reported higher levels of rejection sensitivity, with adolescents who felt more victimized reporting more rejection sensitivity and reported by their peers to be higher in rejection sensitivity.

Second, when we fit multivariate models, the findings were in support of our hypothesis that relational victimization would have the most prominent associations with early adolescents’ loneliness and depressive symptoms. In fact, relational victimization stood out as the only unique direct correlate of loneliness and depressive symptoms, which we did not anticipate. Moreover, as expected, relational victimization had indirect associations with early adolescents’ emotional adjustment via greater self-reported and peer-reported rejection sensitivity. Adolescents who felt that they experienced more gossip, exclusion and other relationally harmful behaviors were more lonely and depressed, and relational victimization was both directly harmful to their socioemotional health, as well as harmful because of its link to greater sensitivity to rejection. These findings reveal the powerful role of relational victimization in socioemotional problems.

These findings extend past cross-sectional (Cole et al. 2010) and longitudinal (Sinclair et al. 2012) research that has identified the greater harm of relational compared to overt victimization for the formation of negative social cognitions, and for the emergence of socioemotional adjustment problems. Although rejection sensitivity was not measured in this past research, previous findings suggest that relational victimization is associated with beliefs in the social world as a threatening and rejecting place. The findings of the present study point to the strong association of relational victimization with socioemotional problems of early adolescents, and extends previous research to show its important link to excessive sensitivity and negative emotional reactions to rejection. Rejection sensitivity is another important social cognitive processing pattern that helps to explain why children exhibit depressive symptoms and feel lonelier relative to their peers.

A third finding was that there were no associations of friendship conflict with rejection sensitivity, even when bivariate associations were examined. Also, there were no significant unique direct associations of friendship conflict with socioemotional adjustment in the multivariate model. Hence, relational victimization was the only unique correlate of depressive symptoms and loneliness. Why might this be the case? As others have argued (see Sinclair et al. 2012), it could be that relational victimization, given its covert nature, is more resistant to intervention either by victims or by others. Relational victimization also might be easier to maintain and, hence, be more chronic than physical/overt victimization given its covert nature. Moreover, relational victimization might be more difficult for young people to understand, which could limit their capacities to implement cognitive or behavioral actions to aid optimum coping. We can add to this that early adolescents prefer self-management of bullying and victimization, but increasingly do want to seek support from peers, rather than from adults, for interpersonal stress at school (Zimmer-Gembeck and Skinner 2011). This could make relational victimization particularly difficult given that it is targeted toward damaging relationships, especially relationships with those who can provide the very support that early adolescents prefer. It also might be exceedingly difficult given the far-reaching threat to self-perceptions and social relationships, which together can exceed the limits of adolescents’ own social and cognitive capacity to change.

Similar arguments might be made about friendship conflict. Relational aggression and victimization can occur within friendship groups, with some victimized adolescents connected to popular or high status groups but others more isolated from their peers (Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2013). Friendship conflict has both positive and negative components. Friendship conflict is probably a normal part of many close friendships, but it may be that the most negative and distressing aspects of friendship conflict involve relational aggression and victimization. The short measure of friendship conflict used in the present study might have been insufficient to assess when conflict was highly aversive and implied rejection versus when it was a normal part of close friendships and was positively resolved or easily negotiated. In future research, friendship intimacy and conflict resolution might be taken into account.

The fourth finding was that rejection sensitivity did moderate the association between friendship conflict and emotional adjustment, but none of the other possible ten moderation effects were supported suggest the same. Hence, friendship conflict was associated with emotional maladjustment but this association differed depending on early adolescents’ level of rejection sensitivity. In particular, moderation was supported for friendship conflict by peer reports of rejection sensitivity when examining depressive symptoms, and was supported for friendship conflict by self-reports of rejection sensitivity when examining loneliness. Nevertheless, these findings of only two moderation effects out of the 12 tested suggest that moderation does not extend across different forms of peer relationship problems and may only occur with one or the other measure of rejection sensitivity used here.

Moreover, the two moderation effects that were found were not consistent with our expectations. Although we did find that adolescents with high rejection sensitivity and highly aversive social experiences were particularly high in emotional maladjustment, we did not find that aversive social experience was more strongly associated with depressive symptoms and loneliness in this high rejection sensitivity group. Instead, high rejection sensitivity seemed to identify young people with adjustment problems regardless of their level of aversive peer experiences (in this case, friendship conflict), and it was adolescents with low rejection sensitivity that seemed most affected by their social experiences. Although further research clearly is needed to confirm and expand upon these findings, this seems to suggest that dispositional factors that infuse the adolescent with negative views and expectations of rejection may overshadow any enhancement to adjustment that could come from positive social experiences. Also, when adolescents’ dispositions are more positive, social experiences deserve attention because they can have an enhanced impact on their adjustment. These findings are consistent with recent research that identifies the cost of negative self and relationship views for emotional functioning even when relationships are positive, but also the impact that negative social experiences can have when they are inconsistent with positive views of the self and others (Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2007).

A fifth finding was that overt victimization was associated with greater peer reports of rejection sensitivity, despite having no unique direct or indirect associations with emotional adjustment in the multivariate model. Hence, perceived overt victimization was relevant to peers’ observations of their classmates as more highly sensitive and reactive to rejection. This is the first study that has shown that rejection sensitivity, when the respondent is other than the self, can identify the negative impact of overt victimization on rejection sensitivity even after accounting for the strong effects of relational victimization.

The sixth finding was that we found no evidence of gender moderation of any associations in our multivariate model. Although some past research has found that victimization may be more strongly associated with depressive symptoms or loneliness or with self-conceptions for one gender or the other (Sinclair et al. 2012) and friendship conflict may be more damaging to the socioemotional adjustment of girls than boys (Newman Kingery et al. 2011), our findings better support the universal theoretical significance of aversive social experiences for a range of mental health disorders (Baumeister and Leary 1995). However, consistent with other research on the differences in levels of many of the variables measured in the present study (Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2005), we did find differences in levels of overt victimization and friendship conflict, with boys reporting more than girls. We also found that girls report more rejection sensitivity than boys.

Finally, another aspect of this study also deserves discussion. A unique extension on previous research was the development of a peer-report measure of rejection sensitivity, which was found to be correlated modestly with self-reported rejection sensitivity. Surprisingly, however, this correlation was stronger than was found in previous research focused on reports of internalizing behaviors within friendship dyads (Swenson and Rose 2009). Additionally, each measure had similar associations with depressive symptoms and loneliness, and similar associations with other measures when bivariate associations were compared, and most of these remained significant in the multivariate model. These are striking results for a peer-report measure given that the majority of past research considers self-views more predictive of mental health problems than views from other reporters (Graham et al. 2003; Zimmer-Gembeck et al. 2007). Future research to replicate and extend the understanding of peer-reported rejection sensitivity will be important for understanding how children make these judgements about rejection sensitivity, and whether peer-reported rejection sensitivity is associated with other problem symptoms and behaviors. This strongly suggests that adolescents do observe and can report some of the cognitive and affective patterns that are linked to overperceiving rejection and being more emotionally reactive when it is perceived. What adolescents particularly attend to in order to make these interpretations of others is a topic for future research.

In addition to the limited measure of friendship conflict, there are three other study limitations to mention. First, mostly white Australians participated, which limits generalizability. Second, all associations were concurrent. Hence, no conclusions about temporal associations or direction of effects can be made. However, the findings are consistent with other longitudinal research of conceptions of relationships and socioemotional adjustment. Yet, it is possible that depressive symptoms and loneliness also precede aversive peer relationships and rejection sensitivity (Tran et al. 2012) making associations bidirectional and reciprocal, or that loneliness may play a role in the development of depression over time (Epkins and Heckler 2011). Third, all measures were self-report except the peer-report of rejection sensitivity. This was intentionally done to examine how peer-reports of rejection sensitivity might be used to identify and predict self-perceived socioemotional adjustment. However, future research could benefit from gathering information about victimization from peers.

Conclusions

Previous research has recognised rejection sensitivity as an important correlate of social and emotional problems among adolescents and adults (Downey and Feldman 1996; Downey et al. 2004). Yet, the pathways linking multiple forms of aversive peer experiences (overt victimization, relational victimization, and friendship conflict) to depressive symptoms and loneliness via early adolescents’ rejection sensitivity had not been examined previously. Therefore, one new finding of the present study was the identification of relational victimization as a unique correlate of early adolescents’ loneliness and depressive symptoms, which is direct but also partly indirect via their rejection sensitivity. Additionally, by incorporating a peer-report measure of rejection sensitivity in addition to the commonly used self-report measure, it was shown that these associations extend beyond common method variance. Moreover, moderation also was tested, which showed the importance of examining early adolescents’ rejection sensitivity combined with their friendship conflict to understand their unique and interactive roles in depressive symptoms and loneliness. Taken together, these findings suggest a significant role of relational victimization in expectations and anxiety about rejection, which account for early adolescents’ greater loneliness and more elevated depressive symptoms. They also suggest that high rejection sensitivity is a particular concern given its link with elevated levels of emotional maladjustment even when adolescents report few aversive peer experiences, but findings also suggest the importance of aversive peer experiences especially among adolescents low or moderate in rejection sensitivity. Future research could extend the model tested here to include additional antecedents and outcomes of rejection sensitivity, when measured using multiple methods.

Investigating mediational pathways and interactions between individual characteristics (such as rejection sensitivity) and social histories have the potential to identify when and why the symptoms of depression and loneliness emerge and escalate over time (see also Rudolph and Asher 2000; Rudolph et al. 2000). Hence, the current findings also have applied implications. First, interventions focused on rejection sensitivity and a history of social problems or success might be required starting prior to early adolescence to have positive effects on adolescents’ emotional and social development. Second, practitioners should assess rejection sensitivity and social relationship experiences, preferably relying on multiple reporters, to determine what to address to reduce depressive symptoms and loneliness. For some young people, they may need more assistance with perceptual and processing biases, but other young people may benefit for a stronger emphasis on social intervention to practice forming new friendships and improve existing relationships with peers and others. Third, peers could be allies in these processes given their ability to report about the problems that may be occurring with others in their school. They may be able to provide information useful for identifying young people at risk and also be important participants in school-based interventions.

Overall, these results suggest the importance of focusing on aversive peer experiences, particularly relational victimization, as well as early adolescents’ tendency to overperceive and overreact to rejection, in order to understand the development of depression and loneliness. The findings also raise the possibility of focusing more intense efforts on interventions that address relational victimization and rejection sensitivity, also making a case for the roles of peers in identifying those at risk who may benefit from such interventions. Taken together, a focus on aversive peer experiences and rejection sensitivity is important for moving forward research to understand adolescents’ emerging symptoms of depression and feelings of loneliness and to intervene to improve their adjustment during adolescence and into adulthood.

References

Abela, J. R. Z., & Hankin, B. L. (2009). Cognitive vulnerability to depression in adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In S. Nolen-Hoeksema & L. M. Hilt (Eds.), Handbook of depression in adolescents (pp. 335–376). New York: Routledge.

Adler, P. A., & Adler, P. (1998). Peer power: Preadolescent culture and identity. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Bauman, S. (2008). The association between gender, age, and acculturation, and depression and overt and relational victimization among Mexican American elementary students. Journal of Early Adolescence, 28, 528–554. doi:10.1177/0272431608317609.

Baumeister, R. M., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness-of-fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Butler, J. C., Doherty, M. S., & Potter, R. M. (2007). Social antecedents and consequences of interpersonal rejection sensitivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1376–1385. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.006.

Card, N. A., & Hodges, E. V. E. (2008). Peer victimization among schoolchildren: Correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 451–461. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00562.x.

Card, N. A., Stucky, B. D., Sawalani, G. M., & Little, T. D. (2008). Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development, 79, 1185–1229. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x.

Cassidy, J., & Asher, S. R. (1992). Loneliness and peer relations in young children. Child Development, 63, 350–365. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01632.x.

Chango, J. M., McElhaney, K. B., Allen, J. P., Schad, M. M., & Marston, E. M. (2012). Relational stressors and depressive symptoms in late adolescence: Rejection sensitivity as a vulnerability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 369–379. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9570-y.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Coppotelli, H. (1982). Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18, 557–570. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.18.4.557.

Cole, D. A., Maxwell, M. A., Dukewich, T. L., & Yosick, R. (2010). Targeted peer victimization and the construction of positive and negative self-cognitions: Connections to depressive symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39, 421–435. doi:10.1080/15374411003691776.

Crick, N. R. (1996). The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Development, 67, 2317–2327.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66, 710–722. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x.

Cross, D., Shaw, T., Hearn, L., Epstein, M., Monks, H., Lester, L., & Thomas, L. (2009). Australian Covert Bullying Prevalence Study (ACBPS). Child Health Promotion Research Centre, Edith Cowan University, Perth. Retrieved from http://foi.deewr.gov.au/documents/australian-covert-bullying-prevalence-study-executive-summary.

Cullerton-Sen, C., & Crick, N. R. (2005). Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: The utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social-emotional adjustment. School Psychology Review, 34, 147–160.

Downey, G., Bonica, C., & Rincon, C. (1999). Rejection sensitivity and adolescent romantic relationships. In W. Furman, B. Bradford Brown, & C. Feiring (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 148–174). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Downey, G., & Feldman, S. I. (1996). Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 1327–1343. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1327.

Downey, G., Irwin, L., Ramsay, M., & Ayduk, O. (2004). Rejection sensitivity and girls’ aggression. In M. M. Moretti, C. L. Odgers, & M. A. Jackson (Eds.), Girls and aggression: Contributing factors and intervention principles (pp. 7–25). New York: Kluwer.

Downey, G., Lebolt, A., Rincon, C., & Freitas, A. L. (1998). Rejection sensitivity and children’s interpersonal difficulties. Child Development, 69, 1074–1091. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06161.x.

Epkins, C. C., & Heckler, D. R. (2011). Integrating etiological models of social anxiety and depression in youth: Evidence for a cumulative interpersonal risk model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 329–376. doi:10.1007/s10567-011-0101-8.

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016.

Graham, S., Bellmore, A., & Juvonen, J. (2003). Peer victimization in middle school. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 19, 117–137. doi:10.1300/J008v19n02_08.

Harter, S. (2012). The construction of the self: Developmental and sociocultural foundations (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Kovacs, M. (1985). The Child’s Depression Inventory (CDI). Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 21, 995–998.

London, B., Downey, G., & Bonica, C. (2007). Social causes and consequences of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 481–506. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00531.x.

McDonald, K. L., Bowker, J. C., Rubin, K. H., Laursen, B., & Duchene, M. S. (2010). Interactions between rejection sensitivity and supportive relationships in the prediction of adolescents’ internalizing difficulties. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 563–574. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9519-4.

McLachlan, J., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & McGregor, L. (2010). Rejection sensitivity in childhood and early adolescence: Peer rejection and protective effects of parents and friends. Journal of Relationships Research, 1, 31–40. doi:10.1375/jrr.1.1.31.

Nangle, D. W., Erdley, C. A., Newman, J. E., Mason, C. A., & Carpenter, E. M. (2003). Popularity, friendship quantity, and friendship quality: Interactive influences on children’s loneliness and depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 546–555. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_7.

Newman Kingery, J., Erdley, C. A., & Marshall, K. C. (2011). Peer acceptance and friendship as predictors of early adolescents’ adjustment across the middle school transition. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 57, 215–243. http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/mpq/vol57/iss3/2.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2001). Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 173–176. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00142.

Nuijens, K. L., Teglasi, H., & Hancock, G. R. (2009). Self-perceptions, discrepancies between self-and other-perceptions, and children’s self-reported emotions. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 27, 477–493. doi:10.1177/0734282909332290.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Long, J. D. (2002). A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 20, 259–280. doi:10.1348/026151002166442.

Pepler, D. J., Craig, W. M., Connolly, J. A., Yuile, A., McMaster, L., & Jiang, D. (2006). A developmental perspective on bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 376–384. doi:10.1002/ab.20136.

Pronk, R., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2010). It’s “mean”, but what does it mean to adolescents? Aggressors’ and victims’ understanding of relational aggression. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25, 175–204. doi:10.1177/0743558409350504.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). Review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98–131. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 3, Chapter 10). New York: Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470147658.

Rudolph, K. D., & Asher, S. R. (2000). Adaptation and maladaptation in the peer system: Developmental processes and outcomes. In A. J. Sameroff & M. Lewis (Eds.), Handbook of developmental psychopathology (2nd ed., pp. 157–175). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rudolph, K. D., Hammen, C., Burge, D., Lindberg, N., Herzberg, D., & Daley, S. E. (2000). Toward an interpersonal life-stress model of depression: The developmental context of stress generation. Development and Psychopathology, 12, 215–234.

Sandstrom, M. J., Cillessen, A. H., & Eisenhower, A. (2003). Children’s appraisal of peer rejection experiences: Impact on social and emotional adjustment. Social Development, 12, 530–550. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00247.

Sinclair, K. R., Cole, D. A., Dukewich, T., Felton, J., Weitlauf, A. S., Maxwell, M. A., et al. (2012). Impact of physical and relational peer victimization on depressive cognitions in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41, 570–583. doi:10.1080/15374416.2012.704841.

Swenson, L., & Rose, A. (2009). Friends’ knowledge of youth internalizing and externalizing adjustment: Accuracy, bias, and the influences of gender, grade, positive friendship quality, and self-disclosure. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 887–901. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9319-z.

Tran, C. V., Cole, D. A., & Weiss, B. (2012). Testing reciprocal longitudinal relations between peer victimization and depressive symptoms in young adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41, 353–360. doi:10.1080/15374416.2012.662674.

Wang, J., McDonald, K. L., Rubin, K. H., & Laursen, B. (2012). Peer rejection as a social antecedent to rejection sensitivity in youth: The role of relational valuation. Personality and Individual Differences, 53, 939–942. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.07.007.

Weiss, B., Harris, V., & Catron, T. (2002). Development and initial validation of the peer-report measure of internalizing and externalizing behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 285–294. doi:10.1023/A:1015158930705.

Woodhouse, S. S., Dykas, M. J., & Cassidy, J. (2012). Loneliness and peer relations in adolescence. Social Development, 21, 273–293. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2011.00611.x.

Yoshito, K., Tseng, W., Murray-Close, D., & Crick, N. R. (2012). Developmental trajectories of Chinese children’s relational and physical aggression: Associations with social-psychological adjustment problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 1087–1097. doi:10.1007/s10802-012-9633-8.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Geiger, T. C., & Crick, N. R. (2005). Relational and physical aggression, prosocial behavior, and peer relations: Gender moderation and bidirectional associations. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25, 421–452. doi:10.1177/0272431605279841.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Hunter, T., & Pronk, R. E. (2007). A model of behaviours, peer relations and depression: Perceived social acceptance as a mediator and the divergence of perceptions. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26, 273–285. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.3.273.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Nesdale, D., McGregor, L., Mastro, S., Goodwin, B., & Downey, G. Biased perception of peer rejection: Associations with rejection sensitivity, victimization, aggression, and friendship (under review).

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Pronk, R. E. (2012). Relation of depression and anxiety to self- and peer-reported relational aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 38, 16–30. doi:10.1002/ab.20416.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Pronk, R. E., Goodwin, B., Mastro, S., & Crick, N. R. (2013). Connected and isolated victims of relational aggression: Associations with peer group status and differences between girls and boys. Sex Roles, 68, 363–377. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0239-y.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Skinner, E. A. (2011). The development of coping across childhood and adolescence: An integrative review and critique of research. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35, 1–17. doi:10.1177/016502541038492.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere appreciation to Education Queensland, and the personnel and students from the participating schools. We also thank numerous undergraduate and graduate students for assistance with data collection. The Australian Research Council, DP1096183, provided funding for this project.

Author contributions

All authors made significant contributions to this study and manuscript. M.Z-G. conceived of the study, had primary responsibility for the all aspects of study coordination, conducted most analyses, and drafted the manuscript. S.T. assisted with study conception, data collection and analysis, literature review, and writing. Portions of this paper appear in S.T.’s honour’s thesis. D.N. and G.D. assisted with study conception and measurement development. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Peer Nomination Measure of Rejection Sensitivity

Appendix: Peer Nomination Measure of Rejection Sensitivity

-

Item 1. Who expects that other kids won’t like or accept them? (Factor loading = .80).

-

Item 2. Who worries that they will be left out of groups or activities? (Factor loading = .80).

-

Item 3. Who gets angry when they expect to be left out of groups or activities? (Factor loading = .67).

-

Item 4. Who expects to be left out of groups or activities? (Factor loading = .80).

-

Item 5. Who worries that others won’t like or accept them? (Factor loading = .85).

-

Item 6. Who overreacts when they think others won’t like or accept them (Factor loading = .71).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zimmer-Gembeck, M.J., Trevaskis, S., Nesdale, D. et al. Relational Victimization, Loneliness and Depressive Symptoms: Indirect Associations Via Self and Peer Reports of Rejection Sensitivity. J Youth Adolescence 43, 568–582 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9993-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9993-6