Abstract

Using multisource data and multilevel analysis, we propose that the ethical stance of supervisors influences subordinates’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) which in turn influences subordinates’ trust in the organization resulting in their taking increased personal social responsibility and engagement in organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB) oriented toward both the organization and other individuals. Using a multilevel model, we assessed the extent to which ethical leadership and CSR at the work unit level impacts subordinates’ behaviors mediated by organizational trust at the individual level. We employed a sample of 71 work unit supervisors and 308 subordinates from five businesses of a conglomerate company located in mainland China. Subordinates were asked to rate supervisory ethical leadership practices, CSR, and their extent of organizational trust. Supervisors were asked to rate the personal social responsibility taking and OCB of their respective subordinates. A multilevel path analysis revealed that ethical leadership has a positive effect on CSR at the work unit level and that CSR has a positive cross-level effect on organizational trust at the individual level, which in turn significantly and positively impacts OCB through the mediating effect of taking personal social responsibility. Results are discussed in the context of China’s manufacturing sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

China has experienced rapid industrialization and globalization over the last two decades with attendant challenges to the traditional social governance model (Xie et al. 2008). A model of corporate governance with higher moral and ethical standards has recently emerged (Lu 2014). The importance of ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility (CSR) for enhancing employee identification with and contribution to the organization in China is being recognized by scholars of China’s business practice (Newman et al. 2015; Xie et al. 2008). Furthermore, there is scholarly attention to ethical leadership and CSR as key drivers of organizational trust and valued outcomes such as organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (Guh et al. 2013; Lu 2014; Newman et al. 2015; Qi and Liu 2014; Wang et al. 2013). Consequently, we decided to locate our study in the manufacturing sector, the backbone of China’s economic growth and well-being. Enhanced productivity through enlightened management and corporate governance in the manufacturing sector can make a difference to the environment, communities, and well-being of employees.

Apart from a few exceptions (e.g., Hansen et al. 2011; Piccolo et al. 2010; Qi and Liu 2014), much of the research has focused on the direct effects of ethical leadership behavior and CSR on various attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (Brown and Treviño 2006; Newman et al. 2015). Consequently, little is known about the mechanisms through which such effects materialize. Ethical leadership and CSR are recognized as predictors of OCB (Lu 2014; Newman et al. 2015). The role of trust as an outcome of ethical leadership has been investigated from a cognitive, affective, and organizational perspective (Bulatova 2015; Dirks and Ferrin 2002; Lu 2014). The effects of ethical leadership and CSR on OCB were explored in relation to two main intermediary processes. First, the literature suggests that it is through the creation of organizational identification that ethical leadership (Qi and Liu 2014) and CSR (Evans and Davis 2014; Glavas and Godwin 2013) positively influence OCB among employees. Second, that trust might act either as a moderator (Qi and Liu 2014) or as a mediator of the effect of ethical leadership on OCB (Dirks and Ferrin 2002; Lu 2014), and as a mediator of the CSR–OCB relationship (Hansen et al. 2011). Organizational trust has also been proposed as a determinant of job attitudes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intention to quit (Dirks and Ferrin 2002). Further, organizational commitment was proposed as an antecedent of OCB (Guh et al. 2013).

While these findings are valuable in and of themselves, they do not offer a comprehensive picture of the dynamics of ethical leadership and its consequences as they unfold across levels in the organization. More specifically, we do not know how ethical leadership promotes CSR practices and how CSR, in turn, fosters the development of organizational trust among employees. We also do not know of possible sequential mediating effects of CSR and organizational trust on the ethical leadership–OCB relationship (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Glavas and Godwin 2013). Understanding the underlying process by which CSR influences employees is likely to bring sophistication to management theory and management practice leading to more effective organizational intervention (Glavas and Godwin 2013). It will also help us in the creation of more refined models of leadership that leverages CSR toward positive impact on employees (Glavas and Godwin 2013). More importantly, these influences permeate across levels, a process that has not yet been explored (Aguinis and Glavas 2012). While the literature documents the roles of ethical leadership, CSR, organizational trust, individual social responsibility, work attitudes, and OCB, it has failed to capture the complexity of the processes by which these entities influence each other across levels (Aguinis and Glavas 2012).

Ethical leadership at the managerial-level influences CSR actions of the organization (Hemingway and Maclagan 2004). CSR actions and policies in turn permeate across levels to affect employee attitudes and behavior (Aguinis and Glavas 2012). There is a cascading effect of managerial-level CSR on employee actions (Vlachos et al. 2014) and if one were to capture these cascading effects, one needs a multistage model, multisource data, and cross-level analysis to fully appreciate the impact of ethical leadership in organizations and sustain it through enlightened management. In making this claim, we agree with Aguinis and Glavas (2012) that the “first knowledge gap is the need to produce multilevel research” (p. 953). We believe that ethical leadership will bring about much valued OCBs from employees. We argue that such OCBs can be sustained only when employees develop trust in the organization and take personal responsibility toward moving the organization forward by engaging in OCBs. Management has to earn this trust. When an organization engages in socially responsible behavior in a consistent fashion toward all its stakeholders, employees take notice. Such CSR is motivated by and emanates from ethical leadership on the part of management. The purpose of this study is to shed light on the long chain of intermediary factors between ethical leadership and OCB by focusing on the development of shared perceptions of CSR, organizational trust, and responsibility taking behavior as sequential mediating factors.

For our study, we focus on both the supervisors of work units and their subordinates. Specifically, we look at the ethical leadership behavior of the supervisors and the OCB of their respective subordinates including OCBs directed toward one’s coworkers and others in the larger work unit (OCB-I) and OCBs directed toward the organization itself (OCB-O). We employ a multilevel model in which we test how ethical leadership behavior by the supervisor contributes to the development of shared perceptions of CSR among subordinates at the work unit level. We further analyze how such shared perceptions of CSR have a cross-level mediating effect between ethical leadership and individual-level organizational trust. We then explore the role of responsibility taking behavior as a mediator of the organizational trust–OCB relationship at the individual level.

Theory and Hypotheses

Ethical Leadership

Ethical leadership is defined as the demonstration of normatively appropriate behavior in both personal and interpersonal contexts and the active promotion of socially responsible behavior at all levels in the organization reinforcing a moral ethos through communication and ethical decision making (Brown et al. 2005; Snell 2000). Ethical leadership is rooted in the principles of respect, service, justice, honesty, and community (Beauchamp and Bowie 1988). Ethical leadership theory views the phenomenon as resulting from both individual characteristics that include moral reasoning (Ciulla 2005) and situational influences that include a moral context (Brown and Treviño 2006). That said, our interest is more in how ethical leadership plays out in the organization and influences organizational behavior (Hemingway and Maclagan 2004).

Ethical leadership theory suggests that ethical leaders take interactional justice seriously (Chiaburu and Lim 2008; Neubert et al. 2009) and ensure that both external and internal stakeholders are treated fairly and cared for in a consistent manner. This involves investing in the employees of the organization, ensuring their personal growth, engaging other stakeholders in a manner that generates a social consensus in the community, and communicating a sense of social responsibility. By doing so, ethical leaders are perceived as honest and trustworthy by the people they lead (Brown and Treviño 2006; Neubert et al. 2009). Such trust in the leader translates into greater motivation and positive attitudes, such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Neubert et al. 2009). Ethical leaders, being responsible for the welfare of their organization in general and for their followers, model such behavior on a consistent basis (Wood and Bandura 1989). This rubs off on their subordinates as social learning theory would suggest and elicits accountability (Brown and Treviño 2006). In exchange for the social responsibility demonstrated consistently by the leader, the subordinates respond by taking responsibility for organizational welfare, thus strengthening the consensus regarding mutual exchange and obligations (Anderson and Schalk 1998). A subtle form of goal alignment starts taking place as a result of ongoing moral management by the leader (Brown and Treviño 2006). This not only results in the generation of positive attitudes such as job satisfaction and higher commitment to the organization, but also motivates pro-social and extra-role behaviors (Neubert et al. 2009).

This theoretical framework sets the stage for our empirical model. While the theory is rather succinct about the process that links social responsibility to organizational citizenship behavior (Brown and Treviño 2006), we are interested in probing the dynamics of this process and unpacking the conceptual steps involved in how ethical leadership influences organizational citizenship behavior.

In what follows, we develop arguments that stretch out the theoretical arguments into an empirical model that puts forward specific hypotheses that are supported not only by our overarching theoretical framework but also by extant empirical research in parts. Our interest is to verify the theoretical tenets and to reveal the process that would eventually be helpful to design a management system that is driven by ethical leadership. As one can see, the processes of social exchange and social learning inform the substance of the linkages in the model we propose. While ethical leadership theory is not explicit about its reach across levels in the organization, its theoretical links to CSR at the organizational level and trust at the level of individual employees along with attendant attitudes and behaviors that follow justifies a multilevel model of the phenomenon. There is also some empirical evidence for a cascading effect of leadership across levels (Bass et al. 1987).

Ethical Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility

Ethical leadership often plays out through corporate actions that are viewed as socially responsible (Brown et al. 2005). Such actions elicit positive responses from employees because they perceive that they are fairly treated by their supervisors (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005). Ethical leadership is related to several constructive behavioral outcomes such as OCBs (Piccolo et al. 2010), a propensity to take more risks, such as voicing change that can potentially benefit the organization and so forth (LePine and Van Dyne 2001; Qi and Liu 2014). However, employees will be more likely to take risks and go beyond the call of duty when they believe that the organization will act in their best interests and actually see the organization engaging in behaviors that are respectful of its stakeholders. That is how CSR comes into play. As mentioned earlier, studies show that employee perceptions of CSR influence job attitudes, such as organizational commitment, intention to quit, and behavioral outcomes such as OCB (Carmeli et al. 2007; Newman et al. 2015; Rupp et al. 2013; Zhang et al. 2014). However, there is evidence that employees’ perceptions are shaped by their immediate supervisors’ attitudes and behavior (Vlachos et al. 2013; Wood and Bandura 1989). Thus, employees’ reactions to CSR are explained by social influence (Griffin 1983). Supervisors are seen as the most important direct social referents (Dirks and Ferrin 2002; Mayer et al. 2009). Consequently, subordinates will form judgments of CSR based on the information that is communicated by the observed behavior of their immediate supervisors. As a result, subordinates’ perceptions of CSR will be directly impacted by the ethical leadership behavior of their immediate supervisors (Hemingway and Maclagan 2004; Vlachos et al. 2013).

Ethical leadership theory suggests that demonstration of normative behavior in interpersonal relationships will reinforce reciprocal conduct among employees (Brown et al. 2005). We further know that subordinates tend to mimic the behavior of their supervisors (Wood and Bandura 1989). By setting a personal example, leaders model the values of the organization as their moral development renders them sensitive to CSR policies (Snell 2000). This is how ethical leadership shapes the perceptions of CSR and the OCB of employees. Empirical research supports this antecedence of leadership on CSR (Muller and Kolk 2010; Weaver et al. 1999). Aguinis and Glavas (2012) suggest that a sense of duty and justice among the leaders, indicators of ethical leadership, results in CSR behaviors which in turn strengthen employee–organization linkages thus entrenching value alignment. In this process, subordinates perceive themselves as being part of a social exchange with their supervisors and when they perceive the exchange as fair they will reciprocate by going beyond the call of duty to accomplish more (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005).

Hansen et al. (2011) argued that individual-level perceptions of CSR are more relevant for determining the impact of CSR on individual attitudes and behavior. However, the literature suggests that employees not only assess whether they are treated fairly but also make a cognitive evaluation as to how others are treated. So, we argue here that it is the shared perceptions of CSR among employees that contribute to the promotion of discretionary behavior that benefit others and the organization (Bartels et al. 2010). In their conceptual development of CSR, Basu and Palazzo (2008) suggested a process model of organizational sense-making in which the way managers cognitively process and discuss CSR and exemplify CSR through their actions provides information about how employees should respond to key stakeholders. Such process model offers a new perspective that differs from that of a content-based approach to CSR. It focuses on how CSR is enacted in organizations. The signals launched by managers about CSR guide CSR-related activities performed by those who can observe how managers act with respect to stakeholders (Minbaeva 2016). The behavior and discourse of managers shape the mental frames of subordinates in assessing CSR (Mitchell et al. 1997). Moreover, Ciulla (2005) proposed that the congruence between a leader’s discourse and behavior sets the ground for robust relationships characterized by trust and reciprocity. When subordinates receive consistent and clear signals from a supervisor, they are likely to develop common mental frames about CSR. This is more likely to happen when the supervisor is a trusted source as reflected by one’s intrinsic moral character (Ciulla 2005). This means that we should expect differences in perceptions of CSR across work units. The ethical leadership behavior of a supervisor will directly impact sense-making (Weick 1995) among subordinates in a work unit and the development of common mental frames by which subordinates will cognitively process information, think, and act toward stakeholders. Therefore, ethical leadership is essential in shaping positive and consistent perceptions of CSR in a work unit. However, we stress that it is through the shaping of shared perceptions of CSR among subordinates that supervisors elicit consistent constructive behavioral responses on the part of their subordinates. Thus, we offer:

Hypothesis 1

Supervisor’s ethical leadership behavior has a positive effect on shared perceptions of CSR at the work unit level.

Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Trust

CSR policies and guidelines are initiated at the organizational level and serve as key components of the broader institutional context that influences employee behavior (Greenwood and Van Buren 2010). Research shows that employees’ perceptions of CSR at the group-level influence their individual-level organizational identification (Carmeli et al. 2007), engagement (Glavas and Piderit 2009), and OCB (Jones 2010; Lin et al. 2010; Sully de Luque et al. 2008). Therefore, answering the call of Aguinis and Glavas (2012), we propose a cross-level relationship from work unit perceptions of CSR to individual-level organizational trust and attendant individual employee behavioral outcomes.

It should be noted that in our study, supervisors and their subordinates are from various work units from five businesses of a large manufacturing conglomerate company. These different work units involve a variety of industrial processes resulting in various levels of pollution to the environment. Therefore, supervisors who monitor the daily operations have an obligation to fulfill their CSR to various stakeholders. Although CSR policies and guidelines are issued from the top of the organization, supervisors have discretion in interpreting and making decisions with respect to CSR practices. Their leadership therefore shapes socially constructed and shared perceptions of CSR at the work unit level. In sum, it is necessary to study CSR as a group-level phenomenon because supervisors and their subordinates have significant impact on the implementation of CSR and its influence on various stakeholders. Furthermore, research reveals that perceptions of CSR at the work unit level influence individual employee responses and overall performance (Hunt and Jennings 1997).

At the individual level, trust refers to one’s willingness to accept vulnerability to another party based on positive expectations of that party’s actions (Mayer et al. 1995). When employees perceive the organization as socially responsible and benevolent, they are more likely to trust that the organization will treat them fairly. Therefore, employees will become more open to the organization based upon their assessments of the values and ethics of the organization. Therefore, we consider individual-level organizational trust as the most proximal outcome of CSR.

The conception of CSR has the potential to influence organizational trust. For subordinates, CSR provides information about what the organization stands for and what they can expect in terms of personal treatment. Consequently, the perceptions of CSR formed within a work unit communicate information about the responsibility the organization is willing to take vis-à-vis its stakeholders, including employees. CSR can lead to high-trust cultures that minimize transaction costs, bureaucratic control, and conflict (Shockley-Zalabak et al. 2000). When the organization is perceived as benevolent, it reduces uncertainty. The organization is perceived as predictable and as acting in good faith toward its stakeholders (Mayer et al. 1995). However, organizational trust is also influenced by the individual experiences a subordinate has had with the organization. As a trustor, an employee may have experienced violation of trust in the past. Moreover, the trustor may experience high or low value congruence with the organization (Mishra 1996; Shockley-Zalabak et al. 2000). Thus, organizational trust is influenced by CSR activities that are embedded in the cognitive and linguistic processes of stakeholders and by individual experiences with respect to CSR.

This brings attention to the importance of the level of analysis in the conceptualization of organizational trust (Schoorman et al. 2007). Organizational trust can be derived from the actions of leaders and employees’ perceptions of CSR. However, employees’ propensity to trust and identification with the organization play an important role in the development of organizational trust. Therefore, we offer that CSR is a group-level conception shared by a group of subordinates based on the observations of supervisory behavior with respect to CSR practices. Supervisory ethical leadership fosters a common understanding among subordinates as to what responsibility the organization is taking toward its stakeholders. As such, subordinates who work for a supervisor whom they consider an ethical leader are more likely to share consistent perceptions of CSR. This will in turn increase the likelihood that subordinates will trust the organization. However, propensity to trust, identification with the organization, and past experiences among others come into play in developing individual organizational trust. Thus, organizational trust is a complex and dynamic phenomenon that reflects individual differences both within and between work units. Consequently, we do expect that CSR at the work unit level will have an effect on organizational trust at the individual level. Thus, we offer:

Hypothesis 2

Work unit level perceptions of CSR directly and positively impact individual level organizational trust.

We further anticipate that shared perceptions of CSR at the work unit level play a mediating role between supervisory ethical leadership behavior and individual level organizational trust among subordinates. As specified above, supervisors have discretion over the implementation of CSR practices and can use their referent and expert power to influence subordinates who will tend to emulate their respective supervisor. CSR serves as the medium through which ethical leadership is interpreted on an ongoing basis. Supervisory CSR practices can be observed and cognitively processed by subordinates. As such, these CSR practices of a supervisor offer useful cues as to what the organization stands for and as to whether subordinates can expect fair treatment on the part of the organization. Consequently, ethical leadership in this particular context will impact individual-level organizational trust through CSR.

Hypothesis 3

Work unit level perceptions of CSR will mediate the relationship between supervisory ethical leadership behavior and individual level organizational trust.

Organizational Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Studies show that employee organizational trust is positively related to OCB (Dirks and Ferrin 2001; Guh et al. 2013; Hansen et al. 2011). As mentioned earlier, trust refers to one’s willingness to be vulnerable to another party while being cognizant of the fact that the actions and decisions of that other party cannot be monitored and controlled (Mayer et al. 1995). Thus, employees who trust the organization are likely to endorse the organization’s policies and are willing to take risks on behalf of the organization (Guh et al. 2013). Ethical leadership theory (Brown and Treviño 2005) suggests that both trust and job attitudes of employees are influenced by the moral management efforts of their respective leader. In particular, CSR practices oriented toward the well-being of employees build organizational trust (Farooq et al. 2014). We also know that organizational trust positively impacts the organizational commitment of employees (Farooq et al. 2014; Guh et al. 2013; Hansen et al. 2011). Furthermore, research shows that CSR has a positive impact on OCB through organizational trust (Hansen et al. 2011). CSR through the creation of shared meaning (Weick 1995), contributes to the development of a social identity (Tadjfel and Turner 1986), which in turn, influences organizational commitment that leads to OCBs toward one’s coworkers (OCB-I) and toward the employing organization (OCB-O) (Collier and Esteban 2007; Vlachos et al. 2014). However, such commitment is a direct consequence of organizational trust (Hansen et al. 2011). Thus, organizational trust becomes a key driver of both OCB-I and OCB-O.

The relationship between organizational trust and OCBs is conditioned by the extent to which employees are willing to take risks and accept responsibilities (Colquitt et al. 2007). By taking on more responsibilities, employees expose themselves to criticisms and increase their accountability to others. They are willing to do this because they trust the organization and identify with the organization. It is what we call individual social responsibility. Such reciprocity to CSR shows that the ethical leadership effect goes through CSR at the work unit level and organizational trust at the individual level (Bass et al. 1987; Vlachos et al. 2013). Therefore, we believe that organizational trust will engender responsibility taking behavior among subordinates and propose:

Hypothesis 4

Organizational trust has a direct positive impact on subordinate responsibility taking behavior.

Organizational citizenship behavior constitutes discretionary extra-role behavior that can promote the overall welfare of the organization (Organ 1988; Podsakoff et al. 2000). OCBs are directed toward one’s coworkers and other individuals in the organization (OCB-I) as well as toward the organization itself (OCB-O) (LePine et al. 2002). Active pursuit of interpersonal engagement with co-workers (OCB-I) with a view to contribute to the collective welfare of the organization and demonstrating behavior that is in the best interest of the organization (OCB-O) are more likely when employees believe that the organization is cognizant of their welfare and supportive of their efforts. This is what ethical leadership entails (Brown and Treviño 2005). Thus, organizational trust lays the foundations for the emergence of helping behavior in organizations. With trust comes responsibility and with responsibility comes the willingness to take risk. Thus, responsibility taking behavior becomes a mediator of the relationship between trust and OCB. When employees take responsibility above and beyond what is in their job description, they are more likely to engage in behaviors that help others (OCB-I) and that help the organization (OCB-O) (Glavas and Piderit 2009). In other words, taking additional responsibilities above and beyond the call of duty will result in organizational citizenship behaviors directed toward coworkers and the organization. Thus, we offer:

Hypothesis 5a

Taking responsibility has a direct positive effect on OCB-I.

Hypothesis 5b

Taking responsibility has a direct positive effect on OCB-O.

We further propose that organizational trust has an indirect effect on OCB-I and OCB-O through responsibility taking. Individual responsibility taking behavior constitutes a constructive and proactive response to CSR resulting from the ethical leadership behavior of supervisors engendering high organizational trust among subordinates. In the absence of organizational trust, subordinates are more likely to meet the minimum requirements as delineated in their job contract and avoid taking responsibility so as to reduce the likelihood of potential criticisms as a result of their initiative. As such, taking responsibility constitutes a first step toward a subordinate’s full engagement with the organization. When subordinates get involved beyond the call of duty, they become cognizant of the needs of the organization and co-workers and start to engage in pro-social behavior that can benefit the organization in the long run. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 6

The simultaneous effect of organizational trust on OCB-I and OCB-O is mediated by responsibility taking behavior.

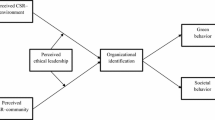

Figure 1 presents the illustration of the conceptual model.

Methods

Context

We contacted five businesses of a conglomerate manufacturing company located in southwest mainland China. The company has operations in various fields including de-sulfurization and de-nitrification, heavy-duty machinery, power transmission, solar grade silicon, industrial control devices, and chemical and maritime equipment.

Procedures

We contacted 150 work units from these five manufacturing businesses. In each unit, we obtained data from various business functions such as research and development, quality assurance, production and operation, administration, customer service, and sales and marketing. Under the support of the director of human resources, we invited one employee per unit to serve as survey coordinator and to collect data. The survey coordinators explained the objectives of the study to the participants and distributed questionnaires to supervisors and subordinates. During the data collection, we ensured the confidentiality of individual responses to increase respondents’ frankness and to decrease their apprehension about evaluation. One of the co-authors who is attached to the institutional research committee reviewed the research protocol in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration. All participants gave their informed consent and were fully informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any point in time.

Sample

Of the 150 work units contacted, 71 agreed to participate in the study. This yielded a total of 71 supervisors and 310 subordinates. After removing unusable data, we had a total of 308 subordinates. The average number of subordinates in each work unit was four. The smallest work unit was composed of three subordinates and the largest of 14 subordinates. The sample of subordinates was composed of 68% males. The average age was 33 years. In terms of education, 7% had completed high school, 31% had done technical college, 35% had an Associate degree, 24% had a Bachelor’s degree, and 3% had a Master’s degree or Doctoral degree. For 71 percent of them, organizational tenure totals more than 3 years. For the supervisors, 87% were males. The average age is 38 years. The level of education was overall higher with 24% with a technical college, 28% with an Associate degree, 41% with a Bachelor’s degree, and 7% with a Master’s degree or Doctoral degree.

The average length of the supervisor–subordinate relationship was 8 years. Subordinates provided ratings on the ethical leadership behavior of their respective supervisors, perceptions of CSR, and extent of organizational trust. Supervisors were asked to rate the responsibility taking behavior and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) of each subordinate.

Measures

The survey items, originally developed in English as part of a larger program of research, were administered in Chinese. We used the classic back-to-back translation procedure to ensure accuracy of meaning (Brislin 1980). We did a pilot test with the Chinese survey instrument after which a small number of items were reworded for clarity. A 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) was used for all items pertaining to the study variables.

Ethical Leadership

Ethical leadership was measured with a 10-item scale developed by Brown et al. (2005). Subordinates were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with provided statements about ethical leadership behavior. A sample item is: “My supervisor sets an example of how to do things in the right way in terms of ethics.” Cronbach alpha is 0.89.

Corporate Social Responsibility

We measured corporate social responsibility with a five-dimensional scale using 20 items from Turker (2009). This measure distinguishes five types of CSR initiatives according to the type of stakeholders targeted: CSR to customers, government and society, environment, employees, and philanthropy. We chose to use all five dimensions of Turker’s measure because we would like to access employees’ overall perceptions of CSR. This is particularly needed in the context of our study, where those manufacturing work units all have some levels of pollution to the environment and responsibilities to the community. Therefore, employees are not only passive members of a corporation, but they are also responsible for CSR practices and contribute to the value of the corporation (Rupp et al. 2013) and multiple stakeholders.

A sample item for socially responsible Human Resources is “Our Company provides a wide range of indirect benefits to improve the quality of employees’ lives.” A sample item for responsibility toward customers is: “Our Company respects consumer rights beyond the legal requirements.” A sample item for responsibility toward society is: “Our Company emphasizes the importance of its social responsibilities to society.” A sample item for responsibility toward the environment is: “Our Company makes investment to create a better life for future generations.” A sample item for philanthropy is: “Our Company makes sufficient monetary contributions to charities.” Cronbach alpha for corporate social responsibility is 0.89. For both ethical leadership behavior and CSR, the individual-level responses were aggregated at the group level by taking the average for each group. The procedure employed for testing the inter-rater agreement is explained below in the aggregation analysis section.

Organizational Trust

The perception of organizational trust was measured with seven items from Robinson (1996) developed after Gabarro and Athos (1976). The subordinates were asked to assess the extent to which they have trust in the organization. A sample item is: “I can expect my organization to treat me in a consistent and predictable fashion.” Cronbach alpha is 0.80.

Responsibility Taking

The 3-item scale from Wagner (1995) was used to measure the extent of responsibility taking behavior in team work. A sample item is “Is responsible for the productivity of the group”. Cronbach alpha is 0.87.

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

We measured OCB-I with seven items and OCB-O with six items from Williams and Anderson (1991). For OCB-I, a sample item is: “Goes out of his/her way to help new employees.” For OCB-O, a sample item is: “Conserves and protects organizational property.” Cronbach alphas were 0.89 and 0.76 for OCB-I and OCB-O, respectively.

Analytic Strategy

We used a multilevel theoretical model and employed nested data to test our model. As shown in Fig. 1, we propose that supervisory ethical leadership and CSR are at the group level while subordinates’ trust in the organization, taking responsibility behavior, and OCBs are at individual level of analysis. We analyzed the interrelationships among variables at both the individual and group levels of analysis. A multilevel path analysis was used to test our hypotheses, which not only offers conventional multilevel modeling procedures, but also allows simultaneous investigation of multiple paths at various levels. We further employed multisource data in order to minimize common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

We used Mplus 6.0 (Muthén and Muthén 2010) program to perform multilevel analysis. Following the procedures outlined by Muthén (1994) and Preacher et al. (2011), we first examined the proportion of between-level variance by computing Type I Intra-class Correlation Coefficients (Raudenbush and Bryk 2002). Then, we computed Rwg(j) statistic (James 1982; James et al. 1993) and ICC(2) to demonstrate acceptable within groups or inter-rater agreement (Klein and Kozlowski 2000). We tested the construct validity of our measures using multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) in order to analyze covariance matrices and factor structure at both within-level and between-level simultaneously (Hox 2002). Finally, multilevel path analysis (MPA) was used to test our hypotheses.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, reliability coefficients, and correlations for the study variables for both individuals and work units.

Aggregation Analyses

The results of one-way ANOVA with random effects show that the between-group variance among study variables was significant at the 0.01 level, which indicates significant between-group difference. The values of type I intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC1) were 0.17 for ethical leadership, and 0.12 for corporate social responsibility. These are considered acceptable according to James (1982). Then, we tested the reliability of group means using ICC(2) as recommended by Schnabel et al. (1998). The ICC(2) were 0.47 and 0.37 for ethical leadership and CSR, respectively. Moreover, the median Rwg(j) values were 0.84 for ethical leadership and 0.80 for CSR. These Rwg(j) values were above the conventionally acceptable Rwg(j) value of 0.70, indicating that work unit inter-rater agreement was strong (James et al. 1993). Taken together, these tests offer support for the aggregation of the data at the group level for both ethical leadership and CSR.

Validity of Measures

We conducted a multilevel confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) to verify the construct validity of the multilevel variables including ethical leadership and CSR. The MCFA was tested using the following steps: (1) conventional confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), (2) between-level variance, (3) within-level factor structure, (4) between-level factor structure, and (5) ML-CFA (Dyer et al. 2005; Muthén 1994). As shown in Table 2, the results of MCFA indicate that the measurement model is acceptable.

We also conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to verify the construct validity of the single-level variables including organizational trust, taking responsibility, OCB-I, and OCB-O. The results show that the measurement model is acceptable (χ2(101) = 357.04, TLI = 0.90, CFI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.09, SRMR = 0.05).

To test for the potential influence of common method variance, we created a latent variable to which OCB-I, OCB-O, and taking responsibility were related. The paths were constrained to be equal and the variance of the common factor constrained to be of a value of 1. The factor loadings for common latent factor were equal to 0.50 before standardization and the t value indicated significance. The common variance was estimated as the square of the common factor loading. The results suggest that there was no significant common method bias with a calculated variance of 24.7%, which is well below the threshold of 50% (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

We further did the zero-constrained test (Lindell and Whitney 2001). We conducted the Chi-square difference test with the constrained model (χ2 = 425.83; df = 91). The results show that the amount of shared variance across all variables was not significantly different from zero. Thus, there was no significant common method bias in the measurement of OCB-I, OCB-O, and taking responsibility.

Hypothesis Testing

We tested the hypothesized model using multilevel path analysis. All the path coefficients were estimated simultaneously. Results show that the model exhibits a satisfactory fit (χ2 = 136.04, df = 44, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.04[within], 0.08[between]).

As indicated in Table 3 and in Fig. 2, supervisory ethical leadership is positively related to the perceptions of CSR at the work unit level (β = 0.24, p < 0.00). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Hypotheses 2 stated that there will be a cross-level direct path between perceptions of CSR at the work unit level and organizational trust at the individual level. Results show a significant cross-level path (β = 0.36, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported. We further tested the cross-level mediation relation using the 95% confidence interval for the indirect effect. The indirect relation between ethical leadership and individual organizational trust via shared perceptions of CSR remains positive (0.09 [95% CI 0.06, 0.12]). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is supported. Table 3 presents the path coefficients and estimated indirect effects.

Hypothesis 4 proposed a direct effect of individual organizational trust on responsibility taking behavior. Results show that organizational trust is positively related to responsibility taking behavior (β = 0.19, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 4 is supported. Furthermore, Hypotheses 5a and 5b proposed that responsibility taking behavior will have a positive effect on OCB-I and OCB-O, respectively. Results reveal that both hypotheses are supported. The relationships between responsibility taking behavior and OCB-I (β = 0.73, p < 0.00) and OCB-O (β = 0.62, p < 0.00) are both significant. The indirect effect of organizational trust on OCB-I (0.14, 95% CI [0.001, 0.276]) and OCB-O (0.12, 90% CI [0.019, 0.215]) are significantly nonzero, thus providing evidence for the mediating effect of responsibility taking, thereby supporting Hypothesis 6.

Discussion

This study highlights the importance of ethical leadership in creating awareness of CSR among the led and shaping their perceptions. We found that perceptions of CSR at the work unit level directly impact organizational trust at the individual level. Moreover, we provided evidence suggesting that ethical leadership elicits organizational trust through shared awareness of CSR among work unit members. We also show that trust in the organization motivates employees to take on additional responsibilities and engage in OCBs.

These findings extend the existing literature in two important ways. The literature as it stands has done a comprehensive job of identifying the relationships among the different components of our model. But they were confined to one or two variables at a time or were mostly at one level of analysis. We first looked at the phenomenon as multifaceted, manifesting itself across levels involving multiple actors. We modeled the phenomenon such that the full impact of ethical leadership unfolded through CSR to creating trust and taking personal responsibility that manifested itself through OCBs. Multiple variables relevant to ethical leadership and CSR were combined in a theoretically robust fashion and tested using a multilevel analysis with multisource data. This inspires confidence toward investing in ethical leadership training for managers as it makes strategic sense. Second, we have broadened the scope of the research on ethical leadership, CSR, and OCB by locating it in China’s manufacturing sector where much of China’s economic well-being is determined.

Instead of measuring ethical leadership in the abstract, we focused on the ethical leadership of a direct referent, namely the supervisor of each participating work unit. This conditioned the respondent to focus on ethical leadership as displayed and practiced by his or her own supervisor, lending authenticity to the measurement. We used a character-based approach to analyze the leadership behavior of the supervisor and demonstrated that the integrity, dependability, and fairness of supervisors influenced the extent to which subordinates trust the organization. However, we noted that the influence of ethical leadership on subordinate trust is a mediated one. If subordinates collectively perceive that the organization supports CSR practices they are more likely to trust the organization. Thus, supervisors make subordinates develop expectations about the organization by modeling socially responsible behavior. When subordinates feel confident that the supervisor and the organization will treat them fairly and be a responsible corporate citizen, they may be more comfortable engaging in behaviors that might otherwise be considered risky. When the organization acts in a consistent and predictable way toward its external and internal stakeholders and invests in CSR practices, it signals to its employees that it is worth exerting extra efforts and to reciprocate by engaging in extra-role behavior. This affirms that the norm of reciprocity influences the way subordinates respond to the treatment they receive from the organization in the context of ethical leadership. In a collectivist culture like that of China, it is expected that the norm of reciprocity is stronger in its facilitation of social exchange. Consequently, trust in the organization displayed at the individual level sets the stage for a fruitful social exchange between the organization and its employees. This study demonstrates that employee’s organizational trust mediates the social exchange process.

Findings indicate that CSR influences the behavioral response of subordinates through organizational trust, which means that the shared perceptions of CSR, when positive, elicit constructive behavior from subordinates through the development of individual trust in the organization. This is in alignment with the tenets of identity theory, which proposes that employees are more likely to identify with the organization when it engages in CSR. This study also shows that subordinates will take on added responsibilities when they trust the organization. This results in their engaging in OCB-I and OCB-O. When employees identify with the organization, their interrelationships with others will be collaborative and supportive. We extend current literature by proposing that shared perceptions of CSR among subordinates influence individual OCB-I and OCB-O through the development of organizational trust and reciprocity. Such reciprocity is illustrated through subordinates taking responsibility when the organization invests in CSR. This corroborates existing literature on the role of organizational trust as a mediator between CSR and OCB. More importantly, our findings underscore the potential of ethical leadership for sustainable pan-organizational influence.

A major strength of this study pertains to its design. We employed multisource data to capture the voice of the participants at each level to ensure authenticity. We also controlled for common method variance using multisource data. We measured the variables at the level where it mattered most (Minbaeva 2016). We focused on ethical leadership and CSR at the group level and organizational trust and behavioral responses at the individual level. The multilevel model provided empirical evidence of a higher quality by controlling for variance at the group and individual levels simultaneously. We demonstrated that shared perceptions of supervisory ethical leadership practices and CSR at the group-level influence organizational trust at the individual level. Thus, we illustrate here that there is a significant cross-level path between-group-level CSR and individual-level organizational trust. By employing a multilevel path analysis, we were able to demonstrate the sequential mediation of group-level CSR, individual-level organizational trust, and taking responsibility, thereby elaborating the effect of supervisory ethical leadership practices on subordinates’ OCBs in much greater detail. Leaders have the power to shape the perceptions of their subordinates. When leaders act in a way that is ethical, they show to their subordinates that CSR is important. It is the development of shared perceptions of CSR that influences the extent to which each employee will be willing to invest in the organization. It is through shaping perceptions that leaders engender subordinates’ organizational trust and as a result, elicit constructive behavior on the part of subordinates.

This study makes an important contribution to the literature by elucidating the long-chain process between ethical leadership behavior at the group level and OCBs at the individual level. Rather than focusing on the job attitudes of subordinates as outcome variables of ethical leadership and CSR that are already well established in the literature, we focused on the group-level and individual-level mediators between ethical leadership and OCB. By shaping the collective perceptions of their subordinates, supervisors contribute to the development of trust in the organization among their subordinates through a positive social construction of CSR. We further propose that it is the shared positive perceptions of CSR that engender organizational trust and that such trust influences subordinates’ constructive behavioral responses. As subordinates take on more responsibilities, it gives rise to extra role behavior directed toward both the organization and coworkers. Taken together, our findings highlight the importance of studying the interrelationships among leadership behavior and OCB using explanatory factors at the group and individual level of analysis. We employed here shared perceptions of CSR at the group level and organizational trust at the individual level as explanatory factors that involve both cognitive and affective processes. Future research should unpack these cognitive and affective processes so as to shed light on how ethical leadership and CSR trigger change in employee behavior.

This study has some limitations. First, although we obtained significant results, a larger sample size would offer more robust findings. Second, the measure of CSR should integrate more HR practices of relevance for employee retention and job performance. Another limitation pertains to the cross-sectional data collection. A longitudinal study would provide more information as to how changes in organizational trust can be triggered by changes in CSR practices and explore possible reciprocal effects. In other words, studying changes in individual trajectories as a result of changes in leadership and CSR practices could yield additional interesting findings to uncover when and how employees invest in OCBs or withdraw their OCBs as leadership and CSR practices change. Researchers could also consider the potential moderating effect of the composition of group members and other characteristics of the group such as size and slack resources. Such factors could very well influence the extent to which employees exhibit OCBs. There is also a need to corroborate this cross-level path over time to see how consistent and enduring it may be as organizational changes get implemented. Nevertheless, the results presented here provide enough evidence to suggest that the cross-level path between CSR at the group level and organizational trust at the individual level is of relevance for understanding the process through which employees decide to take responsibility and engage in OCBs in the context of ethical leadership. Our focus on an emerging economy like China broadens the scope of theoretical guidance for future research on ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility.

In conclusion, we view this study not only as an empirical endorsement of ethical leadership theory as it stands but also as a commentary on the process by which it unfolds. We offer insights as to how ethical leadership plays a crucial role in the implementation of CSR practices, development of shared perceptions of CSR and organizational trust among subordinates in a work unit, and influences behavioral outcomes of relevance to the effectiveness of the organization. We also broaden the empirical base for ethical leadership theory by locating our study in the manufacturing sector in mainland China. We hope that our contribution would pave the way to refine the conceptualization of CSR as a dynamic process among actors in the organization that should be studied with a multilevel approach to unwrap its effect across organizational levels.

References

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research Agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Anderson, N., & Schalk, R. (1998). The psychological contract in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 637–647.

Bartels, J., Peters, O., de Jong, M., Pruyn, A., & van der Molen, M. (2010). Horizontal and vertical communication as determinants of professional and organisational identification. Personnel Review, 39(2), 210–226.

Bass, B. M., Waldman, D. A., Avolio, B. J., & Bebb, M. (1987). Transformational leadership and the falling dominoes effect. Group and Organization Studies, 12(1), 73–87.

Basu, K., & Palazzo, G. (2008). Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sensemaking. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 122–136.

Beauchamp, T. L., & Bowie, N. E. (1988). Ethical theory and business (3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Expanding the role of the interpreter to include multiple facets of intercultural communication. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 4(2), 137–148.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Bulatova, J. (2015). The role of leadership in creation of organisational trust. Journal of Business Management, 9, 28–33.

Carmeli, A., Gilat, G., & Waldman, D. A. (2007). The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment, and job performance. Journal of Management Studies, 44(6), 972–992.

Chiaburu, D. S., & Lim, A. S. (2008). Manager trustworthiness or interactional justice? Predicting organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(3), 453–467.

Ciulla, J. B. (2005). The state of leadership ethics and the work that lies before us. Business Ethics: A European Review, 14(4), 323–335.

Collier, J., & Esteban, R. (2007). Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16(1), 19–33.

Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 909–927.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2001). The role of trust in organizational settings. Organization Science, 12(4), 450–467.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 611–628.

Dyer, N. G., Hanges, P. J., & Hall, R. J. (2005). Applying multilevel confirmatory factor analysis techniques to the study of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(1), 149–167.

Evans, W. R., & Davis, W. (2014). Corporate citizenship and the employee: An organizational identification perspective. Human Performance, 27(2), 129–146.

Farooq, O., Payaud, M., Merunka, D., & Valette-Florence, P. (2014). The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 563–580.

Gabarro, J. J., & Athos, J. (1976). True North: Discover your authentic leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Glavas, A., & Godwin, L. N. (2013). Is the perception of “Goodness” good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(1), 15–27.

Glavas, A., & Piderit, S. K. (2009). How does doing good matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on employees. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 36, 51–70.

Greenwood, M., & Van Buren, H. J., III. (2010). Trust and stakeholder theory: Trustworthiness in the organisation-stakeholder relationship. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 425–438.

Griffin, R. W. (1983). Objective and social sources of information in task redesign: A field experiment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(2), 184–200.

Guh, W., Lin, S., Fan, C., & Yang, C. (2013). Effects of organizational justice on organizational citizenship behaviors: Mediating effects of institutional trust and affective commitment. Psychological Reports: Human Resources and Marketing, 112(3), 818–834.

Hansen, S. D., Dunford, B. B., Boss, A. D., Boss, R. W., & Angermeier, I. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(1), 29–45.

Hemingway, C. A., & Maclagan, P. W. (2004). Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 50(1), 33–44.

Hox, J. J. (2002). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Mahwah, NY: Erlbaum.

Hunt, T. G., & Jennings, D. F. (1997). Ethics and performance: A simulation analysis of team decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(2), 195–203.

James, L. R. (1982). Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67(2), 219–229.

James, L. R., Demaree, R. G., & Wolf, G. (1993). RWG: An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(2), 306–309.

Jones, M. J. (2010). Accounting for the environment: Towards a theoretical perspective for environmental accounting and reporting. Accounting Forum, 34(2), 123–138.

Klein, K. J., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2000). Multilevel theory, research and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

LePine, J. A., Erez, A., & Johnson, D. E. (2002). The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: A critical review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(1), 52–65.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 326–336.

Lin, C., Lyau, N., Tsai, Y., Chen, W., & Chiu, C. (2010). Modeling corporate citizenship and its relationship with organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 357–372.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121.

Lu, X. (2014). Ethical leadership and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating roles of cognitive and affective trust. Social Behavior and Personality, 42(3), 379–390.

Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. B. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108(1), 1–13.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

Minbaeva, D. (2016). Contextualizing the individual in international management research: Black boxes, comfort zones and a future research agenda. European Journal of International Management, 10(1), 95–104.

Mishra, A. K. (1996). Organizational responses to crisis: The centrality of trust. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 261–287). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mitchell, R. K., Agle, B. R., & Wood, D. J. (1997). Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: Defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review, 22(4), 853–886.

Muller, A., & Kolk, A. (2010). Extrinsic and intrinsic drivers of corporate social performance: Evidence from foreign and domestic firms in Mexico. Journal of Management Studies, 47(1), 1–26.

Muthén, B. O. (1994). Multilevel covariance structure analysis. Sociological Methods and Research, 22(3), 376–398.

Muthén, L., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén.

Neubert, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Roberts, J. A., & Chonko, L. B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(2), 157–170.

Newman, A., Nielsen, I., & Miao, Q. (2015). The impact of employee perceptions or organizational corporate social responsibility practices on job performance and organizational citizenship behavior: Evidence from the Chinese private sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26(9), 1226–1242.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lanham, MA: Lexington Book.

Piccolo, R. F., Greenbaum, R., Den Hartog, D. N., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(2–3), 259–278.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Paine, J. B., & Barach, D. G. (2000). Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. Journal of Management, 26(3), 513–563.

Preacher, K. J., Zhang, Z., & Zyphur, M. J. (2011). Alternative methods for assessing mediation in multilevel data: The advantages of multilevel SEM. Structural Equation Modeling, 18(2), 161–182.

Qi, Y., & Liu, M. (2014). Ethical leadership, organizational identification and employee voice: Examining moderated mediation process in the Chinese insurance industry. Asia Pacific Business Review, 20(2), 231–248.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(4), 574–599.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 895–933.

Schnabel, A., Beerli, P., Estoup, A., & Hillis, D. (1998). A guide to software packages for data analysis in molecular ecology. In G. Carvalho (Ed.), Advances in molecular ecology. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Davis, J. H. (2007). An integrative model of organizational trust: Past, present and future. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 344–354.

Shockley-Zalabak, P., Ellis, K., & Winograd, G. (2000). Organizational trust: What it means, why it matters? Organizational Development Journal, 18(4), 35–48.

Snell, R. S. (2000). Studying moral ethos using an adapted Kohlbergian model. Organization Studies, 21(1), 267–295.

Sully de Luque, M., Washburn, N. T., Waldman, D. A., & House, R. J. (2008). Unrequited profit: How stakeholder and economic values relate to subordinates’ perceptions of leadership and firm performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 53(4), 626–654.

Tadjfel, H., & Turner, J. E. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worschel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago, IL: Nelson Hall.

Turker, D. (2009). Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 411–427.

Vlachos, P., Panagopoulos, N. G., & Rapp, A. A. (2013). Feeling good by doing good: Employee CSR-induced attributions, job satisfaction, and the role of charismatic leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(3), 577–588.

Vlachos, P., Panagopoulos, N. G., & Rapp, A. A. (2014). Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi-study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(7), 990–1017.

Wagner, J. A., III. (1995). Studies of individualism-collectivism: Effects on cooperation in groups. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 152–173.

Wang, Y., Tsai, Y., & Lin, C. (2013). Modeling the relationship between perceived corporate citizenship and organizational commitment considering organizational trust as a moderator. Business Ethics: A European Review, 22(2), 218–233.

Weaver, G. R., Treviño, L. K., & Cochran, P. L. (1999). Corporate ethics programs as control systems: Influence of executive commitments and environmental factors. Academy of Management Journal, 42(1), 41–57.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601–617.

Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory of organizational management. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 361–384.

Xie, J. L., Schaubroeck, J., & Lam, S. S. K. (2008). Theories of job stress and the role of traditional values: A longitudinal study in China. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 831–848.

Zhang, M., Fan, D. D., & Zhu, C. J. (2014). High-performance work systems, corporate social performance and employee outcomes: Exploring the missing links. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(3), 423–435.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Animal Research

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this research involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tourigny, L., Han, J., Baba, V.V. et al. Ethical Leadership and Corporate Social Responsibility in China: A Multilevel Study of Their Effects on Trust and Organizational Citizenship Behavior. J Bus Ethics 158, 427–440 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3745-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3745-6