Abstract

While recent studies have increasingly suggested leadership as a major precursor to corporate social responsibility (CSR), empirical studies that examine the impact of various leader aspects such as style and ethics on CSR and unravel the mechanism through which leadership exerts its influence on CSR are scant. Ironically, paucity of research on this theme is more prevalent in the sphere of social enterprises where it is of utmost importance. With the aim of addressing these gaps, this research empirically examines the interaction between ethical leadership and CSR and, in addition, investigates organic organizational cultures (clan culture and adhocracy culture) as mediators in the above interaction. To this end, a model was developed and tested on the sample of 350 middle- and top-level managers associated with 28 Indian healthcare social enterprises, using Structural Equation Modeling Analysis, Bootstrapping and PROCESS. Results reveal that ethical leadership both directly and indirectly influences CSR practices. The indirect influence of ethical leadership involves nurturing clan and adhocracy cultures, which in turn influence CSR. These findings are significant for social enterprise leaders seeking to encourage their organizations’ socially responsible behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, academics have shown considerable interest in examining corporate social responsibility (CSR); much of the initial thrust for research into the social responsibility of organizations came from the corporate sector against the backdrop of major scandals, such as the Enron and WorldCom. More specifically, research has concentrated on consolidating the aspects of corporate leadership that foster ethical and socially responsible behavior on the part of organizations (Angus-Leppan et al. 2010; Groves and LaRocca 2011; Swanson 2008; Waldman et al. 2006a, b; Waldman and Siegel 2008; Wu et al. 2015). Amidst the turmoil created by these scandals, it is ironic that the traditional CSR research has overlooked the prevalence of CSR in a very important sector, the social enterprise sector comprised of social enterprises engaged in commercial activities to accomplish social ends (Dart 2004; Di Domenico et al. 2010). The effectiveness of social enterprises depends upon catering to the expectations of diverse stakeholders (Balser and McClusky 2005; Herman and Renz 1997), and hence the prevalence of CSR practice in these organizations is a subject matter of further enquiry (Cornelius et al. 2008).

This paper has two key objectives. First, it examines the interaction between ethical leadership [the leadership style most eminent in the social enterprise context (De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2008)] and CSR in social enterprises; specifically, it attends to ethical leadership at the level of the CEO in congruence with literature that acknowledges top executives as the prime individuals who can influence CSR initiatives (Swanson 2008; Waldman et al. 2006a, b; Wu et al. 2015). Second, it elaborates on the contribution of the two types of organic organizational cultures, the clan culture and the adhocracy culture, in the link between ethical leadership and CSR in social enterprises. These objectives are significant as they address two key concerns in CSR research: first is a lack of empirical studies that examine the impact of leader aspects such as style and ethics on CSR; and second is a lack of understanding of the underlying mechanisms linking leadership with CSR (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Angus-Leppan et al. 2010; Christensen et al. 2014; Groves and LaRocca 2011; Morgeson et al. 2013). In order to substantiate these objectives, India, which harbors the largest number of social enterprises in the world (Bhalla 2014), is taken up as the apt context for this study.

This work contributes to the extant literature in following ways. Carried out in the sphere of social enterprises, the study contributes to the debate on CSR in social enterprises. Additionally, by examining the role of leader behavior as a precursor to CSR, it heeds to calls for research on the microfoundations of CSR (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Christensen et al. 2014). Specifically, it makes a value-added contribution toward recognizing the potential that ethical leadership holds in advancing scholarship on leadership and CSR, both (Angus-Leppan et al. 2010; Christensen et al. 2014; Groves and LaRocca 2011; Morgeson et al. 2013). Furthermore, this study widens the applicability of organic organizational cultures by demonstrating their role in facilitating an in depth understanding of leadership–CSR association. In the attempt to relate leadership and organizational culture to CSR, it attends to important questions revolving around the role of these two in research on CSR; specifically, questions such as “How is CSR related to effective leadership and the characteristics of top executives?” and “What is the relationship between organizational culture/climate and CSR?” have encouraged research into the liaison between Organizational Behavior (OB) and CSR (Morgeson et al. 2013, p. 820). Therefore, by adopting an OB lens to facilitate a better understanding of CSR, this work contributes to research on the confluence of CSR with two popular OB domains, namely, ‘leadership influences’ and ‘work motivation and attitudes’ (Cascio and Aguinis 2008). Finally, this study contributes to the social work literature encompassing the role of leadership in maximizing social impact.

The rest of this article is structured as follows. The subsequent section pertains to the development of study hypotheses grounded on a review of the related literature. Next, the methodology applied and the results obtained from it are elaborated. The findings are discussed. Then, the implications and future research avenues are offered, followed by the conclusion.

Theory and Hypotheses Development

CSR: An Overview

In the academic literature, the concept of CSR has its roots in the seminal work of Bowen (1953), Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, where social responsibility was first defined as “the obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society” (p. 6). Further, Davis (1960) outlined social responsibility as “businessmen’s decisions and actions taken for reasons at least partially beyond the firm’s direct economic or technical interest” (p. 70). In 1979, Carroll conceptualized CSR (Carroll 1979), and later in 1991 introduced the pyramid of CSR (Carroll 1991, p. 42), which encompasses a spectrum of four kinds of responsibilities, namely, the economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities, the fulfillment of which constitutes the social responsibility of business. Additionally, Carroll elaborated CSR taking into account the perspective of moral management of organization’s stakeholders (shareholders, employees, customers, and the local community) (Carroll 1991). Since then, the field has developed significantly and today houses a great proliferation of approaches/conceptualizations (Aguinis 2011; Carroll 1999; Waddock 2004; Waldman et al. 2006b), each capturing important aspects related to the concept.

This study uses the conceptualization of CSR offered by Aguinis (2011, p. 855): “context-specific organizational actions and policies that take into account stakeholders’ expectations and the triple bottom line of economic, social, and environmental performance.” Underpinning this definition is the notion of the ‘triple bottom line’ within the doctrine of which several mainstream organizations, predominantly the social enterprises, today operate. In essence, it describes the very nature of social enterprises, drives the social mission of these organizations, and motivates social enterprise activity (Chell 2007; Cornelius et al. 2008; Ridley-Duff 2008). Defined around the concept of the ‘triple bottom line’ demarcates social enterprises from economic enterprises (Chell 2007); in reality, it entails “greater complexity at the managerial level for ensuring sustainability” (Chell et al. 2010, p. 488). Therefore, managers in social enterprises need to be increasingly savvy about enacting apt leadership behaviors that may be effective within the context of CSR. Unfortunately, the study and understanding of the relationship of leader behavior to social responsibility with specificity to the social enterprise is still in its infancy. The ensuing write up within this section thus draws upon the extant literature to situate particularly the impact of ethical leadership behavior on CSR in the social enterprise.

Ethical Leadership: A Precursor to CSR

Over the past few years, ethical business practices on the part of managers have gained widespread attention from the international community (Brown et al. 2005; Treviño et al. 2006); consequentially, the term ethical leadership has today become a catchword in business and academic circles. In their work on ethical leadership, Treviño et al. (2000) identified two aspects, the moral person and the moral manager, that leaders ought to exhibit in order to be recognized as ethical leaders. Moral persons hold attributes such as honesty, integrity, and trustworthiness; they engage in ethical behavior and carry out decision making in adherence to ethical principles. Moral managers foster the salience of ethics in the organization by serving as role models for ethical conduct, communicating about ethics, and employing reinforcement systems to hold individuals accountable for apt conduct (Treviño et al. 2000). Although various other leadership styles such as transformational leadership (Bass 1985; Burns 1978), spiritual leadership (Fry 2003) and authentic leadership (Gardner et al. 2005) all capture the moral person aspect in some way, the moral manager aspect in ensuring that leaders do not undermine ethical standards in their quest for achievement of short-term ends, sets ethical leadership apart from these styles (Brown et al. 2005; Brown and Treviño 2006). Incorporating these aspects, Brown et al. (2005) offered a constitutive definition of ethical leadership: “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (p. 120). Prior research recognizes the contribution of ethical leadership toward promoting an extensive range of follower attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (Avey et al. 2011; Brown and Treviño 2006; Brown et al. 2005; De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2008; Mayer et al. 2012; Piccolo et al. 2010; Resick et al. 2013; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Surprisingly, it overlooks the influence of ethical leaders on organizational policies and practices, particularly CSR.

The current effort adopts Brown et al.’s (2005) ethical leadership conceptualization and predicts ethical leadership to encourage CSR practices, for various reasons. First, ethical leadership is characterized by altruism (Kanungo and Mendonca 1996; Resick et al. 2006). Ethical leaders have a broad ethical awareness in that they are concerned about (a) serving the greater good, (b) means, not just ends, (c) long-term, not just the short-term, and (d) multiple stakeholders’ perspectives (Treviño et al. 2003, p. 19). They possess a high ethical orientation, identify the significance of proactively prioritizing ethics, and carry out decision making taking into consideration the long-term interests of the organization and all its stakeholders, and hence demonstrate responsible leadership behavior (Maak and Pless 2006; Treviño et al. 2000; Yukl 2001). Prior research posits that grounded on the stakeholder perspective, ethical leaders in their endeavor to meet stakeholder expectations may chalk out ways to improve the organization’s environmental, social, and ethical performance, and hence promote the pursuit of ethical and socially responsible business practices (Groves and LaRocca 2011; Zhu et al. 2014). Second, recent studies (Brown and Treviño 2006; Jordan et al. 2013; Treviño et al. 2000, 2003) suggest that ethical leaders reflect high levels of moral development, practice values-based management, convey ethical standards to employees to follow, and advance clear sets of ethical policies and programs, which are associated with greater CSR activity in the organization (Valentine and Fleischman 2008). Third, ethical leaders express their fundamental beliefs, and call attention to the ethical consequences and long-term risks associated with decisions that go against the interests of various stakeholders; in doing so, they bring into underway role-modeling and a learning process (Bandura 1977; Brown et al. 2005) that gives an impetus to the pursuit of social responsibility initiatives by individuals in the organization. They imbue in the organizational members ambitions that are in accord with the demands of various stakeholders, and motivate followers to act responsibly and rise above their self-interests for the wider interests of the organization and its stakeholders (Bass and Steidlmeier 1999; Kanungo and Mendonca 1996; Resick et al. 2006). Ethical leaders endorse a broad stakeholder-centric view of the organization; they thus hold importance, specifically in the current context of the social enterprise as they would ensure that practices undertaken attend to the enterprise’s primary objective of stakeholder value maximization. Fourth, ethical leadership is significantly and positively associated with the intellectual stimulation component of transformational leadership (Bedi et al. 2016; Toor and Ofori 2009), which is positively related to CSR practices (Waldman et al. 2006b). Overall, the above arguments suggest that ethical leadership positively affects the organization’s CSR practices.

Hypothesis H1

Ethical leadership has a positive effect on CSR practices.

Ethical Leadership, Organic Organizational Cultures, CSR

Organizational culture represents “a collective phenomenon emerging from members’ beliefs and social interactions (Schneider 1987; Trice and Beyer 1993), containing shared values, mutual understandings, patterns of beliefs, and behavioral expectations (Rousseau 1990) that tie individuals in an organization together over time (Schein 2004)” (Giberson et al. 2009, p. 124). It manifests in different layers within the organization; the most commonly referred layer is that of shared values (Ott 1989; Rousseau 1990; Schein 2004; Trice and Beyer 1993). Shared values “serve the normative or moral function of guiding members… in how to deal with certain key situations” (Schein 2004, p. 29) and can be a “source of identity and core mission” (Schein 2004, p. 30). Rousseau (1990) suggested that values are deep-seated in the layered formation of culture and ought to be examined in order to gain insights into the organization’s culture. Also, it is believed that values (e.g., ethicality, concern for people, and excellence) are endorsed primarily by the organization’s leadership (Schein 2004). The present study thus in line with its stated objectives examines organizational culture through the values shared among individuals in the organization.

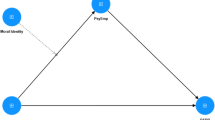

Although the importance of organizational culture in facilitating an understanding of diverse management processes has been abundantly demonstrated, for instance, in terms of achievement of outcomes such as organizational innovativeness (Deshpandé et al. 1993), competitive advantage (Barney 1986), and organizational effectiveness (Denison 1990), the attention accorded to organizational culture in research on CSR is meager. The current research contributes to this line of inquiry by investigating into the crucial role of organizational culture in the liaison between leadership and CSR. Just recently, the academic literature has identified organizational culture as a mediator between leadership and organizational outcomes (Berson et al. 2008). This perspective argues that organizational culture is a reflection of upper echelon leadership (Giberson et al. 2009, p. 125) and explains how leaders influence certain key outcomes. Consistent with this perspective, the current study proposes a model in which ethical leadership influences organic organizational cultures, which in turn are related to CSR practices (see Fig. 1). The model builds on the upper echelons theorization (Hambrick and Mason 1984) as the conceptual foundation for examining the proposed mediation.

Organic organizational cultures, namely clan and adhocracy, are pervasive in organizations in the emerging countries (Appiah-Adu and Blankson 1998; Cameron and Quinn 2006; Wei et al. 2014). Due to their emphasis on flexibility, organic cultures are effective in the rapidly changing and unpredictable environments in such countries (Alvesson and Lindkvist 1993; Burns and Stalker 1961; Ouchi 1980; Covin and Slevin 1989). Since India is an emerging country (International Monetary Fund 2014), the organizations here face volatile environments resulting into the dominance of organic cultures. Additionally, the primacy of collectivistic values and low scores on uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede et al. 2010) evince the importance of these cultures in Indian organizations. Specifically, insights into India’s social enterprise sector communicate its propensity for placing emphasis on the worth of human resource development and innovation so as to remain responsive to the unpredictable market scenario (Intellecap 2012). This study thus attends to organic organizational cultures in the examination of social enterprises in the country. Henceforth, the subsequent paragraphs in this section pertain to the proposed relationships among ethical leadership, the clan and adhocracy organizational cultures, and CSR.

Effect of Ethical Leadership on Clan Culture

The clan culture places a premium on internal maintenance and flexibility; it is characterized by trust, participation, cohesiveness and cooperation, and fosters development of a friendly workplace (Cameron and Quinn 2006). Employee empowerment and commitment are considered key contributors to organizational success, and customers are viewed as partners (Cameron and Quinn 2006). Shared values and goals, and a sense of synergy permeate clan-type organizations; also, such organizations favor leadership styles that embody a concern for people (Cameron and Quinn 2006).

The present work suggests that in order to promote CSR, an ethical leader may encourage clan culture in the organization. Research on leadership and organizational culture postulates that establishing an apt organizational culture is a fundamental task of leaders (Bennis 1986; Davis 1984; Giberson et al. 2009; Tsui et al. 2006). By definition, ethical leaders are altruistically motivated, people-oriented, cooperative, caring, and concerned about maintaining positive relationships with others (Brown and Treviño 2006; Brown et al. 2005; Kanungo 2001; Treviño et al. 2000; Treviño et al. 2003), so, they hold preference for supportive, cohesive and sociable organizational cultures (Brown et al. 2005; Mayer et al. 2012; Pastoriza et al. 2008). Owing to virtues of honesty, trustworthiness, integrity, and fairness, ethical leaders seek to promote trust and loyalty within the organization (Treviño et al. 2000, 2003; Zhu et al. 2004). In addition, ethical leadership has been associated with employees’ organizational commitment (Brown and Treviño 2006; Zhu et al. 2004). For instance, Khuntia and Suar (2004) found that ethical leadership of Indian private and public sector managers empowered subordinates, and enhanced subordinates’ job performance, job involvement, and affective commitment. Prior empirical studies further suggest that ethical leaders have preferences for participative organizational cultures wherein employees have a say in decision making (De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2008). Ethical leaders strive to foster work cultures with high employee morale. For example, De Hoogh and Den Hartog (2008) found that CEO ethical leadership was positively related to top management team (TMT) dynamics that were characterized by higher levels of optimism and effectiveness; members of an effective top management team have a clear understanding of the organization’s mission, and work coherently toward accomplishing it. Overall, ethical leadership seems likely to foster clan culture in the organization.

Hypothesis H2

Ethical leadership favors the development of clan culture.

Effect of Ethical Leadership on Adhocracy Culture

The adhocracy culture emphasizes flexibility and is externally oriented; it is characterized by risk taking, creativity, innovation and adaptability, and fosters development of a dynamic and entrepreneurial workplace (Cameron and Quinn 2006). “Innovative and pioneering initiatives are what lead to success, organizations are mainly in the business of developing new products and services and preparing for the future, and the major task of management is to foster entrepreneurship, creativity, and activity on the cutting edge” (Cameron and Quinn 2006, p. 43). A commitment to experimentation pervades organizations dominated by adhocracy culture. Additionally, such organizations favor visionary and risk-oriented leadership styles (Cameron and Quinn 2006).

The current study posits that ethical leaders may encourage adhocracy culture in the organization in their endeavor to foster CSR. Prior research shows that “leaders with strong ethical commitments who regularly demonstrate ethically normative behavior” (Piccolo et al. 2010, p. 259) tend to build work environments that offer organizational members high levels of autonomy, thereby encouraging members to exhibit productive behaviors at work (Brown et al. 2005; Brown and Treviño 2006; De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2008; Piccolo et al. 2010; Toor and Ofori 2009). Characterized by virtues of: accountability, and a collective orientation for the organization and the society (Resick et al. 2006, 2011), ethical leadership is likely to inspire members to act responsibly to the constantly evolving needs of the organization and the society (Wu et al. 2015), and so create cultures with an external orientation. Owing to high personal moral standards, and preferences for transparency and openness in information sharing (Brown et al. 2005; Treviño et al. 2003), ethical leaders strive to promote high levels of psychological safety and risk taking within the organization (Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). In addition, ethical leadership has been positively associated with employees’ willingness to report problems to management, employee voice, and employee initiative (Brown et al. 2005; De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2008; Kalshoven et al. 2013; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Being primarily people-focused (Treviño et al. 2003), ethical leadership expresses itself in the pursuit of empowerment strategies which encompass developing employees and encourage them for innovation and realization of organizational vision; hence, it seeks to enhance employee self-efficacy (Khuntia and Suar 2004). Workplaces with high self-efficacy among employees tend to be creativity and innovation intensive (Amabile et al. 2004; Kumar and Uzkurt 2011; Hsu et al. 2011; Tierney and Farmer 2002). Also, several studies have emphasized the direct and indirect influence of ethical leadership on employee creativity and innovativeness (Chughtai 2014; Ma et al. 2013; Yidong and Xinxin 2013). More specifically in terms of organizational culture, Toor and Ofori (2009) found that ethical leadership was positively related to transformational culture (Bass and Avolio 1993), which provides a supportive context for innovation. Based on the above argumentation, it seems that ethical leadership fosters adhocracy culture in the organization.

Hypothesis H3

Ethical leadership favors the development of adhocracy culture.

Clan Culture and Adhocracy Culture as Mediators in the Ethical Leadership-CSR Relationship

An organization’s culture affects its CSR policies and practices (Galbreath 2010; Wood 1991; Yu and Choi 2016). In organizations with clan culture, emphasis is laid on the maintenance of cordial relationships; members are expected to be cooperative and other-oriented (Cameron and Quinn 2006). According to Galbreath (2010, p. 515), members’ other orientation in organizations with humanistic cultures is likely to extend beyond the needs and interests of immediate internal members to those of external stakeholders. So they are expected to endeavor to act in response to stakeholder demands for CSR; hence, such cultures are predicted to have a positive effect on the organization’s ability to demonstrate CSR. Furthermore, clan organizations per se value decentralized decision making, open communication, and transparency, collaborate with customers (Cameron and Quinn 2006), and tend to adopt a firm stand on issues of business ethics (Linnenluecke and Griffiths 2010). These attributes promote effective organization-wide information sharing and processing, which in turn enables such organizations to promptly respond to the ever-evolving needs of customers (Wei et al. 2014). Therefore, it appears that clan culture positively affects the organization’s CSR practices.

Hypothesis H4

Clan culture has a positive effect on CSR practices.

Organizations enriched with an adhocracy culture, per se value creativity and innovation, and hold an external orientation (Cameron and Quinn 2006), which motivates them to go beyond the existing standards and devise novel alternative solutions in response to the external dynamism (Lumpkin and Dess 1996; Wei et al. 2014). They show a strong propensity for proactiveness, risk taking, experimentation, and innovation (Cameron and Quinn 2006). Such an entrepreneurial orientation enables the adhocracy organization to seize new opportunities and devote its resources to pursuits that respond to these opportunities, and simultaneously offers the organization the key to broader stakeholder satisfaction (Lumpkin and Dess 1996). In addition, adhocracy organizations encourage the formation of solution-focused ad hoc task teams to address complex challenges (Cameron and Quinn 2006); this approach ensures that environmental, social, and economic considerations are taken into account in management and decision making, and thus promotes the implementation of social responsibility (Zilberg and Galli 2012, p. 213). Moreover, such organizations are mainly involved in introducing new and improved products, processes, and services. Earlier research (Padgett and Galán 2010) has shown that high intensity of these activities positively affects the organization’s prowess to exhibit CSR. Therefore, it appears that adhocracy culture positively affects the organization’s CSR practices.

Hypothesis H5

Adhocracy culture has a positive effect on CSR practices.

Since, hypotheses H2 and H4 suggest that ethical leadership favors the development of clan culture, and clan culture positively affects the organization’s CSR practices, it is expected that ethical leadership has an indirect effect on CSR practices through the clan culture. Empirical studies have substantiated the mediating effect of organizational culture on the ethical leadership–CSR relationship (Wu et al. 2015). Therefore, it is hypothesized:

Hypothesis H6

Clan culture mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and CSR practices.

This mediation hypothesis is theoretically novel and needed for completeness of the model so as to fill the gap in focus. Hence, it is a necessary part of the hypotheses.

As hypotheses H3 and H5 suggest that ethical leadership favors the development of adhocracy culture, and adhocracy culture positively affects the organization’s CSR practices, it is expected that:

Hypothesis H7

Adhocracy culture mediates the relationship between ethical leadership and CSR practices.

All the above-formulated hypotheses are shown in Fig. 1.

Methodology

Sample

The sample for this study was comprised of organizations constituting the health care sector of the Indian social enterprise sphere. Of late, this sector has emerged as a tremendously growing segment within the multi-sectoral social enterprise spectrum (Intellecap 2013). Organizations in this sector are performing yeomen service aimed at catering to the needs of individuals deprived of decent health standards. Further, the awe inspiring leadership in these enterprises is credited with promotion of ethics and adoption of strategies that facilitate optimization of the available talent and technology with the aim of ensuring social responsiveness (Intellecap 2013).

For the purpose of this study, select healthcare organizations were taken up from the social enterprise database available at the Web site of the Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India (List of registered NGO 2014). These organizations are registered as per the registration laws governing social enterprises in India and are situated in the Northern region of the country. In order to ensure the efficacy of the questionnaire, a pilot study was first conducted, eliciting responses from 102 individuals occupying managerial positions (middle and top levels) in these organizations. Subsequent to this, the final data collection was carried out in the time period January, 2015 to June, 2015, through a questionnaire survey, the respondents for which were each organization’s middle- and top-level managers. Given that managers at these levels work in close proximity to the organization’s Chief Executive, they are regarded apt informants of the executive’s leadership behavior (Tsui et al. 2006). Also, keeping in view the designation of these managers, it is surmised that they can provide an insightful analysis of the organization’s culture and CSR. A survey packet was comprised of a cover letter (consisting of the study objectives, the confidentiality certitude, and the request for participation), and the questionnaire was handed over to each participant. This on-site administration of questionnaires facilitated by face-to-face interaction aided elimination of the possibility of inaccurate responses. The respondents provided information regarding: their demographics, the CEO’s ethical leadership behavior, and the organization’s culture and CSR practices.

A total of 32 organizations were approached, out of which 28 were enthusiastic about the study and extended their cooperation in data collection. In total, 410 questionnaires were distributed in these 28 organizations. Out of the 410 questionnaires, 362 were returned, resulting into an 88.29% response rate. Each organization had multiple respondents ranging from ten to fifteen. Twelve incomplete responses were removed. Hence, 350 usable responses were subjected to analysis. Table 1 provides a comprehensive view of the respondents’ demographic information.

Measures

For the study measures, standard scales as furnished by the existing literature were employed. Items constituting these measures were anchored along a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. Brown et al.’s (2005) ten-item instrument, the ethical leadership scale (ELS) was used to measure ethical leadership. The measures, clan culture and adhocracy culture, each included six items based on Cameron and Quinn’s (2006) Organizational Culture Assessment Instrument (OCAI). These culture types are expounded on the basis of the organization’s characteristics, organizational leadership, management of employees, organizational glue, strategic emphasis, and the criteria of success (Cameron and Quinn 2006). The measure, corporate social responsibility, was assessed using eighteen items. These items are based on the work of Torugsa et al. (2013), that employed a twenty-seven item CSR construct. In concordance with the suggestions of ten experts (five industry experts and five subject experts), out of the twenty-seven items, eighteen items were retained as most appropriate for the current study. Table 3 presents an elaborated view of the items corresponding to all of the above measures. Additionally, organization size and age, the most commonly studied contextual variables, were incorporated in the model so as to control for their potential effects on CSR. Organization size was measured by the logarithm of the number of employees, and years of establishment of the organization provided the organization age.

Empirical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 20 and AMOS version 21. At the outset, the data were subjected to an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA). Then, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) (Anderson and Gerbing 1988) comprised of: Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) for validating the basic structure of the constructs in the proposed model, and path analysis for examining the study hypotheses illustrated in the model, was utilized as the analytic approach. That is, the approach encompassed: (a) the measurement model evaluation and (b) the structural model evaluation (Schreiber et al. 2006).

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Factor Identification

The EFA results reported a .920 Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, which being above 0.6 is not only acceptable, but is also excellent as per Kaiser’s recommendations (Hair et al. 2010; Kaiser 1974); also, the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was ascertained to be significant at p < 0.001. Principal component analysis in unison with varimax rotation resulted into identification of four components with Eigen values greater than 1, and reported a 73.662% cumulative variance explained (Hair et al. 2010; Kaiser 1974). The rotated component matrix as well yielded four components comprised of items with factor loadings above .7 (Hair et al. 2010) (see Table 3).

Common Method Bias Check

To control for the common method variance problem that might arise due to data collection using same-source self-reports, the Harman’s one-factor test was employed (Podsakoff and Organ 1986). The first factor exhibited 43.432% variance (<50%). Thus, common method bias was elucidated as not an issue in the current work.

Measurement Model Evaluation

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 conveys the means, standard deviations and correlations of the study constructs. Means and standard deviations of the constructs ranged from 4.3908 to 5.0553 and 1.23543 to 1.67821, respectively. With regard to correlations between the constructs, the correlation coefficients revealed that all taken up constructs are distinct and the highest correlation exists between clan culture and CSR (r = .631, p < 0.01).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

Before proceeding to the testing of study hypotheses, CFA was employed to examine the model fit and assess the reliability, convergent validity and discriminant validity of the multi-item constructs.

Assessment of Measurement Model Fit

Maximum likelihood estimation was utilized for testing each construct’s measurement model. The standardized factor loadings of items constituting various constructs were found to be significant and greater than 0.70. Model fitness was determined using the ensuing fit indices: χ 2/degrees of freedom; goodness-of-fit index (GFI); root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA); adjusted GFI (AGFI); normed fit index (NFI); comparative fit index (CFI); parsimony goodness-of-fit index (PGFI); parsimonious normed fit index (PNFI). Values obtained corresponding to the indices related to individual construct’s measurement model met the statistical standards recommended in the literature (Bagozzi and Yi 1988; Bentler and Bonett 1980; Hu and Bentler 1995; Jöreskog and Sörbom 1984). The overall measurement model capturing all of the study constructs also very well met the goodness-of-fit norms as indicated by its fit indices (χ 2/df = 2.286, GFI = .82, RMSEA = .073, AGFI = .78, NFI = .895, CFI = .933, PGFI = .674, PNFI = .798).

Assessment of Reliability

Examining the statistical scale reliability of all constructs is essential for determining the quality of the internal structure of the proposed model. The criteria for establishing scale reliability involve inspecting: (a) the factor loadings of individual items of each construct (≥0.7), (b) CR, i.e., the composite reliability of each construct (≥0.6), and (c) C-α, i.e., the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of each construct (≥0.6) (Bagozzi and Yi 1988; Fornell and Larcker 1981; Hair et al. 2010). Table 3 evinces the satisfaction of these criteria in that (a) the factor loadings of all items ranged from .712 to .908 and were statistically significant (p < 0.001), (b) the Composite Reliabilities of all constructs ranged from 0.915 to 0.978, and (c) the values of Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of all constructs ranged from 0.914 to 0.978.

Assessment of Validity

Results provided in Table 4 indicate the convergent and discriminant validity of the taken up constructs.

Convergent Validity

The above-mentioned reliability analysis that exhibits significant factor loadings of individual items and satisfactory values of construct reliabilities endorses the convergent validity of the constructs (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Bagozzi and Yi 1988). Furthermore, in accordance with the approach of Fornell and Larcker (1981) and Hair et al. (2010), the convergent validity of the constructs was established by their Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values, which ranged from 0.645 to 0.715 and were found to be higher than the threshold value of 0.5 and lower than their CR values.

Discriminant Validity

The correction coefficients among the study constructs (ranged from 0.210 to 0.603) were lower than the squared root of the AVE value of each of the constructs (the squared root of the AVE of the constructs ranged from 0.803 to 0.846); also the Average Shared Variance (ASV) and Maximum Shared Variance (MSV) values of each construct were lower than its AVE value; this being commensurate with the discriminant validity criteria put forth by Fornell and Larcker (1981) and Hair et al. (2010) established the constructs’ discriminant validity.

Structural Model Evaluation

Having accomplished the validation of the measurement model, the structural model was estimated using path analysis to evaluate the hypothesized relationships among the constructs in the study model.

Assessment of Structural Model Fit

The structural path model (see Fig. 2) contains hypothesized paths among ethical leadership, clan culture, adhocracy culture, and CSR. It shows the values of the path estimates. The fit indices obtained corresponding to this model (χ 2/df = 2.291, GFI = .872, RMSEA = .069, AGFI = .831, NFI = .90, CFI = .95, PGFI = .694, PNFI = .814) meet the model fit benchmarks mentioned in the preceding subsection and demonstrate the path model’s satisfactory fit to the data.

Assessment of the Hypothesized Paths

Tables 5 and 6 report the results of the SEM analysis applied to examine the study hypotheses. These are elaborated below:

Evaluation of direct effects (see Table 5): The SEM results substantiated the significant and positive impact of ethical leadership on CSR as is demonstrated by β = .276 at p < 0.001. Hence, hypothesis H1 was supported. Next, hypothesis H2 is concerned with the association between ethical leadership and clan culture. It was supported in its entirety as ethical leadership was shown to have a significant and positive impact on clan culture (β = .22, p < 0.001). Hypothesis H3 concerned with the association between ethical leadership and adhocracy culture was supported as ethical leadership was shown to have a significant and positive impact on adhocracy culture (β = .37, p < 0.001). In the hypothesis H4, it is postulated that clan culture positively relates to CSR. Full support was found for this hypothesis. In cognizance with β = .58, p < 0.001, a strong and significant association between clan culture and CSR was established. The hypothesis H5 proposed that adhocracy culture positively relates to CSR. As shown in Table 5, adhocracy culture has a strong and significant association with CSR (β = .29, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis H5.

Evaluation of indirect effects (see Table 6): It involved performing the mediation analysis in accordance with the approach recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986). This approach suggests that the independent variable must be associated with the dependent variable, the independent variable must be associated with the mediator, the mediator must be associated with the dependent variable, and inclusion of the mediator should either lower (partial mediation) or lend insignificance to (full mediation) the prior direct association of the independent variable with the dependent variable.

Hypotheses H6 and H7 deal with the impact of ethical leadership on CSR via the clan culture and the adhocracy culture, respectively. In line with Baron and Kenny’s recommendations, support to hypotheses H1, H2, H3, H4 and H5 substantiated the first three conditions. The next key step was to examine the impact of inclusion of clan culture and adhocracy culture on the relationship between ethical leadership and CSR.

On introducing clan culture and controlling for the effect of adhocracy culture, a decrease in the value of the path estimate corresponding to the impact of ethical leadership on CSR was observed, however it remains significant (β = .15, p < 0.001). This implies that there is a reduction in the direct influence of ethical leadership on CSR in the presence of clan culture, and demonstrates the partially mediating role of clan culture in the ethical leadership–CSR linkage. Next, on introducing adhocracy culture and controlling for the effect of clan culture, a decrease in the value of the path estimate corresponding to the impact of ethical leadership on CSR was observed, however it remains significant (β = .13, p < 0.001). This implies that there is a reduction in the direct influence of ethical leadership on CSR in the presence of adhocracy culture, and demonstrates the partially mediating role of adhocracy culture in the ethical leadership–CSR linkage.

An added endeavor consisting of an analysis of the simultaneous impact of clan and adhocracy cultures on the ethical leadership–CSR linkage was made. The structural model depicting this is shown in Fig. 2.

Since on introduction of the mediating variables, a reduction in the effect of ethical leadership on CSR was observed, it is deduced that clan culture and adhocracy culture partially mediate the impact of ethical leadership on CSR. Thus, hypotheses H6 and H7 were empirically endorsed. Finally, the impact of control variables on the dependent variable proved insignificant, therefore, they were not included in the results.

Furthermore, to ensure robustness of mediation, Bootstrap analysis using AMOS was performed with 95% CI (confidence interval). Estimate obtained corresponding to the direct impact of ethical leadership on CSR was .276; estimate obtained corresponding to the indirect impact of ethical leadership on CSR via clan culture was .159; estimate obtained corresponding to the indirect impact of ethical leadership on CSR via adhocracy culture was .264. Thus, the Bootstrap results (see Table 7) comprising of direct, indirect, and total effects substantiated the deduction made above with regard to the partial mediating effect of the two organic cultures.

In addition to the above analysis, application of the SPSS macro, PROCESS (Hayes 2013) for examining the indirect effect of ethical leadership on CSR provided significant information. Table 8 presents the results obtained on analyzing the hypothesized relationships via PROCESS. The numbers obtained were highly convincing with regards to the partial mediation of the two cultures between ethical leadership and CSR. This backed hypotheses H6 and H7.

Hence, ethical leadership significantly influences CSR directly, as well as indirectly through its influence on the clan culture and the adhocracy culture, both of which in turn influence CSR.

Discussion

This empirical study adds to our understanding of the association of ethical leadership with CSR, and the potential mechanisms underlying this association. In consistency with the upper echelons theory, it establishes that organic organizational cultures serve as mediators in the ethical leadership–CSR linkage. The study results offered support for all hypotheses depicted in the proposed model. They demonstrate that the direct effect of ethical leadership on CSR is significant, and so is the indirect effect of ethical leadership on CSR via organic cultures. Findings pertaining to the indirect effect of ethical leadership through clan and adhocracy cultures yield deeper insights into the relationship between ethical leadership and CSR. Both, the internally oriented clan culture and the externally oriented adhocracy culture were found to partially mediate the ethical leadership–CSR relationship. This mediating role of organizational culture reiterates the upper echelons theorization, that is, organizational culture contributes significantly toward bridging leadership and organizational outcomes (Berson et al. 2008). The study findings can be grounded on the rationalization that the behavior of ethical leaders is inclined toward a concern for both internal and external stakeholders (Treviño et al. 2000), and by the same token, internal and external orientation is reflected by the clan and adhocracy cultures, respectively (Cameron and Quinn 2006).

Importantly, this study elaborates on the interaction among ethical leadership, organic organizational cultures, and CSR, specifically in the context of social enterprise, an earlier unexplored sector. It offers initial corroboration of the key role of organic cultures in augmenting the prowess of ethical leadership as a driver of CSR in social enterprises. In doing so, it intends to benefit social enterprise leaders by enhancing their understanding on the type of cultures that are crucial and need to be encouraged in order to manage the organization’s responsiveness to its stakeholders, and so facilitate organizational effectiveness. Besides this, the study extends understanding of the non-existence of mutual exclusiveness between different forms of organic cultures (Deshpandé et al. 1993; Hartnell et al. 2011). By demonstrating the co-existence of organic clan and adhocracy cultures as supportive in the ethical leadership–CSR link, it emphasizes that the complementarity of cultures is crucial for the realization of desirable organizational outcomes.

Additionally, the study results are consistent with previous studies linking leadership and CSR (Waldman and Siegel 2008; Waldman et al. 2006b, Wu et al. 2015; Yukl 2001). Specifically, they empirically support Siegel’s perspective on values-driven CSR in demonstrating ethical leadership marked by the leader’s morality as instrumental in driving CSR (Waldman and Siegel 2008). The present research holds that this driving effect is pronounced in social enterprises, since leaders in these organizations are primarily accountable to the wide array of stakeholders and are concerned with achievement of the organization’s social mission. Hence, in accordance with prior studies, an organization’s leadership does impact organizational outcomes in the form of CSR. Extending this, the research maintains that organizational culture is instrumental in this impact, since in accordance with the findings, the leader’s behavior determines the organization’s culture which in turn determines the organization’s CSR.

Implications

Looking at the pertinence of CSR in terms of effectiveness of social enterprises, this study has major implications for such organizations. As per the study results, social enterprise leaders aspiring for the realization of organizational effectiveness through social responsiveness are encouraged to follow an ethical course of action, since ethical leadership behavior is found to be associated with the organization’s high propensity to engage in CSR activities. Having and communicating a code of ethics is something customary in the social enterprise scenario; what matters is that enterprise leaders need to walk the talk (Ciulla 1999) by themselves resorting to ethical and pro social behavior. This walk the talk of ethics by the upper echelon leaders would facilitate successful management of responsiveness, and would progressively channelize their efforts to guide their organizations to socially productive outcomes; since when executives on account of their cordial characteristics and ethical values exhibit ethical behavior, they are able to subsequently nurture humane and enterprising cultures, which give an impetus to CSR practices and hence are of great import in leveraging the organization’s resources toward the attainment of its social objective.

Furthermore, in accordance with the current study findings, there is high likelihood of demonstration of CSR by organizations wherein clan and adhocracy cultures are encouraged. Therefore, social enterprise leaders in their endeavors to enhance social impact should pay attention to their organizations’ culture, since culture could act as a key factor that may heighten the pursuit of socially responsible practices. It is crucial for them to comprehend the cultures of their organizations and work toward advancing cultures that are supportive of CSR.

Next, this study has implications with respect to the executive hiring criteria in social enterprises. Since top executives are mainly held responsible for the overall organizational success, organizations in the social enterprise ambit are encouraged to set quality hiring standards that take into account ethicality in addition to assessing other leadership qualities of prospective CEOs (Wu et al. 2015). Study findings point out that the effectiveness of managerial appointments in such organizations would depend on the assessment of individuals’ abilities to nurture CSR favorable organizational cultures so as to facilitate the creation of a CSR enabling environment, and further realization of the organization’s social objectives. By and by, key implications are offered to HR practitioners therein, as they are encouraged to include ethics as an indispensable element of the leadership appraisal and development processes (Groves and LaRocca 2011) so as to gravitate ethical individuals to executive appointments. Further, they are advised to embed social responsibility programs in the leadership development agenda, since doing so can develop individuals’ abilities to foster CSR supportive values in the organization. Also, this would have an added benefit in terms of a positive influence on employee performance and hence overall organizational performance, as found by a recent global study conducted by the Korn Ferry Hay Group (Basu 2016).

Implications with Regard to Recent Developments in India’s Social Enterprise Landscape

An examination of the current scenario prevailing in India’s Social Enterprise Landscape reveals a ‘bubble building’ situation constituted by a sharp drop in funding and impact investment (Karunakaran 2013). Such dire state of affairs envisages a situation where in social enterprise leaders would be entangled in commercial concerns, and social enterprises would be exposed to the risk of mission drift (Karunakaran 2013). Therefore, the current scenario has ramifications not only for social enterprises, but also the complete social setup of the country as it is deteriorating the capability of the social enterprise system to deliver social value. Amid tough financial conditions, social enterprise leaders have begun to face catch-22 situations demanding realization of competing objectives: maximizing returns and creating social impact. Social enterprises are coping with the mammoth challenge of sustaining their socially responsible stance. Adding to this, the internal ethos of these organizations is also being marred by the existing dynamics. Practices focused on employee development, employee participation in decision making, transparency are diminishing in terms of being managerial priorities (Dart 2004; Eikenberry 2009; Ohana et al. 2012). Effective management of social enterprises is becoming an uphill task. But, for dealing with the disorder prevailing in the social economy, sound social enterprise management is a sine qua non. Herein, the findings established by the present study are of worth for social enterprises.

Governance is a key facet of social enterprise management (Low 2006). Good governance is an absolute necessity to deal with the existing dynamics (Bakker et al. 2014). Ethical leadership as substantiated by the current study holds tremendous potential for ensuring that the socially responsible stand of the organization be nurtured and sustained, and hence warrants good governance for avoiding mission drift. Social enterprise leaders are therefore suggested to resort to ethical behavior; doing so, they can shape an organizational milieu that is conducive to the resolution of accountability issues arising from multifarious stakeholders’ expectations. By nurturing clan and adhocracy cultures in the organization, leaders in social enterprises can elicit positive outcomes in terms of social impact maximization. They can further these organic cultures by endorsing employee management practices such as participative decision making, autonomy, employee development, encouraging teamwork and employee voice. Such practices would enable the leader commit the available human and financial resources toward achievement of the enterprise’s mission. Since leaders by being ethical can provide a moral compass to the organization and succeed in taking the organization in the right direction, they can ensure the organization’s sustainability in the long run.

Thus, the study findings by facilitating an enhanced understanding on social enterprise management provide crucial inputs to practitioners in the country’s social sector. Since India is a developing economy, the authors opine that these findings and their implications hold importance for other developing economies as well.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The current study has some limitations. First, as it absolutely attends to the effect of organic cultures, studying the impact of mechanistic cultures on the leadership–CSR association is an important avenue for future research and will provide additional insights into when and how leadership influences the organization’s ability to demonstrate CSR.

Second limitation of this work is its cross-sectional research design restricting causal elucidation of the examined relationships among the key study variables. The inferred directionality of relationships is grounded on backing by the contemporary literature. Further, it might be that the predominance of a specific type of culture actuates a particular type of CSR practices which may either be socially concentrated, or economic, or environment related. It might as well be that cultural consensus around specific organizational values effects the leadership–outcomes relationship in unexpected ways (Jaskyte 2004). Therefore, the possibility of intricate causal relationships among the worked upon variables cannot be ruled out. To address this limitation, future studies utilizing a longitudinal research design are encouraged.

Third, this study utilized the same source, i.e., middle- and top-level managers for rating CEO ethical leadership, organic organizational cultures, and CSR. Ratings of organizational culture from the CEO, and those of CEO ethical leadership and CSR from multiple TMT members other than the CEO (Wu et al. 2015), i.e., data collection from multiple informants, would aid in enrichment of the validity of various findings. Additionally, it would be really interesting and value adding that a multilevel approach encompassing aggregation of data from one level to another be followed in subsequent research, for instance, by aggregating information at an organizational level such that it reflects the average assessment on CEOs ethical leadership and CSR.

Fourth, the current work is limited with regard to generalizability as it was carried out in the healthcare organizations constituting a particular category of social enterprises; also, the possibility of a selection bias cannot be ruled out since the participant organizations were those that were quite keen to provide their input for the study. Therefore, future studies may seek to substantiate the study findings on a wider sample.

Finally, the moderating effects of certain variables on the leadership–CSR association can be further studied. For instance, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is a single study that demonstrates moderation by exploring the role of managerial discretion as the moderator in the ‘ethical leadership–social responsibility’ relationship (Wu et al. 2015). The authors echo the call of Wu et al. (2015) to examine the role of boundary conditions of leadership (Mumford and Barrett 2012) that may have an impact on the organization’s CSR.

Conclusion

Putting in a nutshell, this empirical study elaborates on the mediation mechanism that sheds light on how ethical leadership influences CSR practices, which hold extreme importance in the light of effectiveness of particularly the social enterprises. It demonstrates that ethical leadership positively affects CSR; also, ethical leadership favors the development of clan and adhocracy organizational cultures, which in turn have a positive effect on CSR practices. Conclusively, it provides significant insights for social enterprises in their endeavors to become socially responsive and develop their potential for creating a positive social impact.

Change history

27 June 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

References

Aguinis, H. (2011). Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 855–879). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Alvesson, M., & Lindkvist, L. (1993). Transaction costs, clans and corporate culture. Journal of Management Studies, 30(3), 427–452.

Amabile, T. M., Schatzel, E. A., Moneta, G. B., & Kramer, S. J. (2004). Leader behaviors and the work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 5–32.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(5), 411–423.

Angus-Leppan, T., Metcalf, L., & Benn, S. (2010). Leadership styles and CSR practice: An examination of sensemaking, institutional drivers and CSR leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(2), 189–213.

Appiah-Adu, K., & Blankson, C. (1998). Business strategy, organizational culture, and market orientation. Thunderbird International Business Review, 40(3), 235–256.

Avey, J. B., Palanski, M. E., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2011). When leadership goes unnoticed: The moderating role of follower self-esteem on the relationship between ethical leadership and follower behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(4), 573–582.

Bagozzi, R., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94.

Bakker, A., Schaveling, J., & Nijhof, A. (2014). Governance and microfinance institutions. Corporate Governance, 14(5), 637–652.

Balser, D., & McClusky, J. (2005). Managing stakeholder relationships and nonprofit organization effectiveness. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 15(3), 295–315.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 656–665.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and performance beyond expectations. New York: Basic Books.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Administration Quarterly, 17(1), 112–121.

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181–217.

Basu, S. (2016, March 31). Social responsibility programs have positive impact: Study. The Economic Times. Retrieved from http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/jobs/social-responsibility-programs-have-positive-impact-study/articleshow/51630699.cms

Bedi, A., Alpaslan, C. M., & Green, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics, 139(3), 517–536.

Bennis, W. (1986). Leaders and visions: Orchestrating the corporate culture. In M. A. Berman (Ed.), Corporate culture and change. New York: The Conference Board Inc.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606.

Berson, Y., Oreg, S., & Dvir, T. (2008). CEO values, organizational culture and firm outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(5), 615–633.

Bhalla, N. (2014, April 10). Social entrepreneurs battle bureaucracy, need help to expand. Reuters. Retrieved from http://in.reuters.com/article/2014/04/10/india-entrepreneurs-idINDEEA3909420140410

Bowen, H. R. (1953). Social responsibilities of the businessman. New York: Harper & Row.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Burns, T., & Stalker, G. M. (1961). The management of innovation. London: Tavistock.

Cameron, K. S., & Quinn, R. E. (2006). Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework (Rev. ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34(4), 39–48.

Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business and Society, 38(3), 268–295.

Cascio, W. F., & Aguinis, H. (2008). Research in industrial and organizational psychology from 1963 to 2007: Changes, choices, and trends. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1062–1081.

Chell, E. (2007). Social enterprise and entrepreneurship. International Small Business Journal, 25(1), 5–26.

Chell, E., Nicolopoulou, K., & Karataş-Özkan, M. (2010). Social entrepreneurship and enterprise: International and innovation perspectives. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 22(6), 485–493.

Christensen, L. J., Mackey, A., & Whetten, D. (2014). Taking responsibility for corporate social responsibility: The role of leaders in creating, implementing, sustaining, or avoiding socially responsible firm behaviors. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(2), 164–178.

Chughtai, A. A. (2014). Can ethical leaders enhance their followers’ creativity? Leadership, 12(2), 230–249.

Ciulla, J. B. (1999). The importance of leadership in shaping business values. Long Range Planning, 32(2), 166–172.

Cornelius, N., Todres, M., Janjuha-Jivraj, S., Woods, A., & Wallace, J. (2008). Corporate social responsibility and the social enterprise. Journal of Business Ethics, 81(2), 355–370.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1989). Strategic management of small firms in hostile and benign environments. Strategic Management Journal, 10(1), 75–87.

Dart, R. (2004). The legitimacy of social enterprise. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 14(4), 411–424.

Davis, K. (1960). Can business afford to ignore social responsibilities? California Management Review, 2(3), 70–76.

Davis, S. M. (1984). Managing corporate culture. New York: Ballinger.

De Hoogh, A. H. B., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2008). Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader’s social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates’ optimism: A multi-method study. The Leadership Quarterly, 19(3), 297–311.

Denison, D. R. (1990). Corporate culture and organizational effectiveness. New York: Wiley.

Deshpandé, R., Farley, J. U., & Webster, F. E. (1993). Corporate culture, customer orientation, and innovativeness in Japanese firms: A quadrad analysis. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 23–37.

Di Domenico, M. L., Haugh, H., & Tracey, P. (2010). Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 681–703.

Eikenberry, A. (2009). Refusing the market: A democratic discourse for voluntary and nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(4), 582–596.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Fry, L. W. (2003). Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 14(6), 693–727.

Galbreath, J. (2010). Drivers of corporate social responsibility: The role of formal strategic planning and firm culture. British Journal of Management, 21(2), 511–525.

Gardner, W. L., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., May, D. R., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2005). “Can you see the real me?” A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 343–372.

Giberson, T. G., Resick, C. J., Dickson, M. W., Mitchelson, J. K., Randall, K. R., & Clark, M. A. (2009). Leadership and organizational culture: Linking CEO characteristics to cultural values. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24(2), 123–137.

Groves, K. S., & LaRocca, M. A. (2011). An empirical study of leader ethical values, transformational and transactional leadership, and follower attitudes toward corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 103(4), 511–528.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. (1984). Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9(2), 193–206.

Hartnell, C. A., Ou, A. Y., & Kinicki, A. (2011). Organizational culture and organizational effectiveness: A meta-analytic investigation of the competing values framework’s theoretical suppositions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(4), 677–694.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: Guilford Press.

Herman, R. D., & Renz, D. O. (1997). Multiple constituencies and the social construction of nonprofit organization effectiveness. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 26(2), 185–206.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hsu, A., Hou, S., & Fan, H. (2011). Creative self-efficacy and innovative behavior in a service setting: Optimism as a moderator. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 45(4), 258–272.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1995). Evaluating model fit. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 76–99). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Intellecap. (2012). Understanding human resource challenges in the indian social enterprise sector. Hyderabad: Intellecap.

Intellecap. (2013). Pathways to progress a sectoral study of indian social enterprises. Hyderabad: Intellecap.

International Monetary Fund. (2014, October). World Economic Outlook (WEO): legacies, clouds, uncertainties. Retrieved November 18, 2014, from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2014/02/pdf/text.pdf.

Jaskyte, K. (2004). Transformational leadership, organizational culture, and innovativeness in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 15(2), 153–168.

Jordan, J., Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Finkelstein, S. (2013). Someone to look up to: Executive-follower ethical reasoning and perceptions of ethical leadership. Journal of Management, 39(3), 660–683.

Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1984). Lisrel VI. Analysis of linear structural relationships by maximum likelihood, instrumental variables, and least squares methods. Mooresville, IN: Scientific Software.

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36.

Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D. N., & De Hoogh, A. H. B. (2013). Ethical leadership and followers’ helping and initiative: The role of demonstrated responsibility and job autonomy. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(2), 165–181.

Kanungo, R. N. (2001). Ethical values of transactional and transformational leaders. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 18(4), 257–265.

Kanungo, R. N., & Mendonca, M. (1996). Ethical dimensions of leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Karunakaran, N. (2013, July 23). Social Enterprises: Bubble building within the space, creating fissures in the sector. The Economic Times. Retrieved from http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2013-07-23/news/40749657_1_social-entrepreneurs-social-enterprises-social-sector

Khuntia, R., & Suar, D. (2004). A scale to assess ethical leadership of Indian private and public sector managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 49(1), 13–26.

Kumar, R., & Uzkurt, C. (2011). Investigating the effects of self efficacy on innovativeness and the moderating impact of cultural dimensions. Journal of International Business and Cultural Studies, 4(1), 1–15.

Linnenluecke, M. K., & Griffiths, A. (2010). Corporate sustainability and organizational culture. Journal of World Business, 45(4), 357–366.

List of registered NGO. (2014). In Department of empowerment of persons with disabilities. Retrieved November 20, 2014, from http://disabilityaffairs.gov.in/content/page/list-of-registered-ngo.php

Low, C. (2006). A framework for the governance of social enterprise. International Journal of Social Economics, 33(5/6), 376–385.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. G. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21(1), 135–172.

Ma, Y., Cheng, W., Ribbens, B. A., & Zhou, J. (2013). Linking ethical leadership to employee creativity: Knowledge sharing and self-efficacy as mediators. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41(9), 1409–1419.

Maak, T., & Pless, N. M. (2006). Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society—A relational perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 66(1), 99–115.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 151–171.

Morgeson, F. P., Aguinis, H., Waldman, D. A., & Siegel, D. S. (2013). Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 805–824.

Mumford, M. D., & Barrett, J. D. (2012). Leader effectiveness: Who really is the leader? In M. G. Rumsey (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of leadership. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195398793.013.0025.

Ohana, M., Meyer, M., & Swaton, S. (2012). Decision-making in social enterprises: Exploring the link between employee participation and organizational commitment. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(6), 1092–1110.

Ott, J. S. (1989). The organizational culture perspective. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks-Cole.

Ouchi, W. G. (1980). Markets, bureaucracies, and clans. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(1), 129–141.

Padgett, R. C., & Galán, J. I. (2010). The effect of R&D intensity on corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 93(3), 407–418.

Pastoriza, D., Ariño, M. A., & Ricart, J. E. (2008). Ethical managerial behavior as antecedent of organizational social capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(3), 329–341.

Piccolo, R. F., Greenbaum, R., Den Hartog, D. N., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(2–3), 259–278.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544.

Resick, C. J., Hanges, P. J., Dickson, M. W., & Mitchelson, J. K. (2006). A cross-cultural examination of the endorsement of ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(4), 345–359.

Resick, C. J., Hargis, M. B., Shao, P., & Dust, S. B. (2013). Ethical leadership, moral equity judgments, and discretionary workplace behavior. Human Relations, 66(7), 951–972.

Resick, C. J., Martin, G. S., Keating, M. A., Dickson, M. W., Kwan, H. K., & Peng, C. (2011). What ethical leadership means to me: Asian, American, and European perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 101(3), 435–457.

Ridley-Duff, R. (2008). Social enterprise as a socially rational business. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 14(5), 291–312.

Rousseau, D. M. (1990). Assessing organizational culture: The case for multiple methods. In B. Schneider (Ed.), Organizational climate and culture (pp. 153–192). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schein, E. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40(3), 437–453. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1987.tb00609.x.

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–337.

Swanson, D. L. (2008). Top managers as drivers for corporate social responsibility. In A. Crane et al. (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 227–248). Norfolk: Oxford University Press.

Tierney, P. A., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137–1148.

Toor, S., & Ofori, G. (2009). Ethical leadership: Examining the relationships with full range leadership model, employee outcomes, and organizational culture. Journal of Business Ethics, 90(4), 533–547. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0059-3.

Torugsa, N. A., O’Donohue, W., & Hecker, R. (2013). Proactive CSR: An empirical analysis of the role of its economic, social and environmental dimensions on the association between capabilities and performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(2), 383–402.

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56(1), 5–37.

Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P., & Brown, M. E. (2000). Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, 42(4), 128–142.

Treviño, L. K., Weaver, G. R., & Reynolds, S. J. (2006). Behavioral ethics in organizations: A review. Journal of Management, 32(6), 951–990. doi:10.1177/0149206306294258.

Trice, H. M., & Beyer, J. M. (1993). The cultures of work organizations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Tsui, A. S., Zhang, Z.-X., Want, H., Xin, K. R., & Wu, J. B. (2006). Unpacking the relationship between CEO leadership behavior and organizational culture. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(2), 113–137.

Valentine, S., & Fleischman, G. (2008). Professional ethical standards, corporate social responsibility, and the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(3), 657–666. doi:10.1007/s10551-007-9584-0.

Waddock, S. (2004). Parallel universes: Companies, academics, and the progress of corporate citizenship. Business and Society Review, 109(1), 5–42.

Waldman, D. A., de Luque, M. S., Washburn, N., House, R. J., et al. (2006a). Cultural and leadership predictors of corporate social responsibility values of top management: A GLOBE study of 15 countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 823–837.

Waldman, D. A., & Siegel, D. (2008). Defining the socially responsible leader. Leadership Quarterly, 19(1), 117–131.

Waldman, D. A., Siegel, D. S., & Javidan, M. (2006b). Components of CEO transformational leadership and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Management Studies, 43(8), 1703–1725.

Walumbwa, F. O., & Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and workgroup psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1275–1286.

Wei, Y., Samiee, S., & Lee, R. P. (2014). The influence of organic organizational cultures, market responsiveness, and product strategy on firm performance in an emerging market. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(1), 49–70. doi:10.1007/s11747-013-0337-6.

Wood, D. J. (1991). Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of Management Review, 16(4), 691–718.

Wu, L. Z., Ho, K. K., Yim, F. H., Chiu, R., & He, X. (2015). CEO ethical leadership and corporate social responsibility: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(4), 819–831. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2108-9.

Yidong, T., & Xinxin, L. (2013). How ethical leadership influence employees’ innovative work behavior: A perspective of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(2), 441–455.