Abstract

This study examines to what extent perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR) reduces employee cynicism, and whether trust plays a mediating role in the relationship between CSR and employee cynicism. Three distinct contributions beyond the existing literature are offered. First, the relationship between perceived CSR and employee cynicism is explored in greater detail than has previously been the case. Second, trust in the company leaders is positioned as a mediator of the relationship between CSR and employee cynicism. Third, we disaggregate the measure of CSR and explore the links between this and with employee cynicism. Our findings illustrate that the four distinct dimensions of CSR of Carroll (economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary) are indirectly linked to employee cynicism via organizational trust. In general terms, our findings will help company leaders to understand employees’ counterproductive reactions to an organization, the importance of CSR for internal stakeholders, and the need to engage in trust recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In March 2016, a French company called Isobat Experts was forced to close because its entire staff went on sick leave. No epidemics had occurred; this was merely a reflection of the malaise that the company’s employees were feeling due to their new working conditions, which they described as bullying.

As this example suggests, cynicism among employees has increased in recent years (Mustain 2014) and has a significant impact on companies’ performance (Chiaburu et al. 2013). There are three dimensions to organizational cynicism (Dean et al. 1998). The first is cognitive: employees think that the firm lacks integrity. The second is affective: employees develop negative feelings toward the firm. The third is behavioral: employees publicly criticize the firm (Dean et al. 1998). The behavioral dimension of cynicism may have a direct impact on the organization’s performance. When employees engage in bitter and accusatory discourse, this damages the company’s image and the atmosphere in the workplace, and it is frequently accompanied by a lack of personal investment on the employees’ part (Kanter and Mirvis 1989). Surprisingly, although the academic literature on cynicism is growing, scholars have focused on the cognitive and affective dimensions of employee cynicism (Ajzen 2001; Özler and Atalay 2011) and neglected the behavioral aspect—and yet it is key to understand this behavioral dimension if we are to help managers reduce such behavior.

In order for cynicism to be reduced, firms need to create a positive working environment. One pivotal tool in such efforts appears to be corporate social responsibility (CSR). CSR, the widely accepted concept that brings together economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary responsibility (Carroll 1979), has a significant positive effect on a variety of stakeholders (Fonseca et al. 2012; Luo and Bhattacharya 2006; Schuler and Cording 2006; Aguinis and Glavas 2012). Some studies have examined the effectiveness of CSR activities in influencing internal stakeholders (Rupp et al. 2006) or employees (Morgeson et al. 2013; Aguilera et al. 2007) and shown that CSR can increase positive employee behavior through organizational commitment (Brammer et al. 2007) or by reducing employee turnover intention (Hansen et al. 2011). CSR-related efforts increase employees’ positive behaviors. Though little scholarly attention has thus far been paid to whether CSR could potentially decrease negative or counterproductive employee behavior (Aguinis and Glavas 2012), it is not unreasonable to suggest that this may be the case. Furthermore, by corroborating this assumption, we could help managers to decrease deviant behaviors such as those stemming from employee cynicism.

Employees have become suspicious of their leaders and their ability to lead organizations properly (Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly 2003), and so the perception that CSR efforts are being undertaken is not always sufficient to secure a positive overall image of a given company in its employees’ eyes. In the absence of trust, CSR efforts may not be perceived positively at all. For this reason, trust may be a key mediator in the relationship between perceptions of CSR and the reduction of cynical behaviors. Trust is defined as “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor” (Mayer et al. 1995, p. 712). Employees who trust their company leaders will believe in their good intentions and perceive their CSR efforts positively. The converse also appears to be true: the PwC 17th Annual Global CEO Survey (Preston 2014) argues that one of the main business pillars for reducing a trust deficit in leaders is a genuine attempt to target a socially centered purpose. In addition, we know that trust emerges in an environment that employees deem to be trustworthy (Albrecht 2002). We argue that a socially responsible strategy on the part of a corporation can create such an environment.

This article seeks to investigate the impact of perceived CSR on the behavioral dimension of employee cynicism. This impact may be direct or indirect, and is also dependent upon a variable that has been shown to be an important outcome of CSR: trust (Pivato et al. 2008; Hansen et al. 2011).

Literature

A Social Exchange Relationship Between Employees and Their Organization

Social exchange theory is one of the main approaches to the employee–organization relationship and argues that employees’ relationship with an organization is shaped by social exchange processes (Blau 1964; Gouldner 1960; in Coyle-Shapiro and Conway 2004). Individuals develop specific behaviors as an exchange strategy to pay back the support they receive from the organization. In their relationship with the organization and the leaders, if they do not feel that they are trustworthy, they may consider withdrawal or negative behaviors as an acceptable exchange currency and a means of reinstating equity in the social exchange (Settoon et al. 1996).

When employees feel respected and perceive their firm to be attentive and honest, they will most likely feel obliged to act for the good of the firm and take care to not harm its interests (Settoon et al. 1996; Wayne et al. 1997). The firm, meanwhile, should feel an obligation to consider the well-being of its employees if it desires their trust and commitment (Eisenberger et al. 2001).

This type of link is particularly true in the case of CSR (El Akremi et al. 2015; Farooq et al. 2014; Glavas and Godwin 2013). CSR (or a lack of it) precedes employees’ behaviors. Rupp et al. (2006) show that in situations of organizational justice or injustice, employees react according to the principle of reciprocity: reactions are positive if employees feel a sense of justice, whereas they are vengeful if their sentiment is one of the injustices. Thus, CSR is conceptualized as an antecedent of employees’ behaviors (Rupp et al. 2006). Discussing their celebrated model of CSR, Aguilera et al. (2007) state: “When organizational authorities are trustworthy, unbiased, and honest, employees feel pride and affiliation and behave in ways that are beneficial to the organization” (Aguilera et al. 2007, p. 842). Employees react positively to positive CSR (El Akremi et al. 2015), and so CSR fosters positive employee behaviors as the consequence of an exchange process (Osveh et al. 2015, p. 176). For employees, the impression that company leaders are engaging in CSR leads to a general perception of justice, where all stakeholders are treated fairly; in other words, “these CSR perceptions shape the employees’ subsequent attitudes and behaviors toward their firm” (Aguilera et al. 2007, p. 840).

Extant theory clearly asserts that CSR increases positive social relationships and behaviors within organizations (Aguilera et al. 2007), but we do not yet know whether this link is direct or otherwise. Recent empirical research has confirmed that employees are attuned to their organization’s actions, which they use to assess the character of the organizational leaders behind them (Hansen et al. 2013). Social exchange is characterized by undetermined obligations and uncertainty about the future actions of both partners in the exchange. This relational uncertainty accords trust a key role in the process of establishing and developing social exchange (Cropanzano and Mitchell 2005).

Negative social exchange situations will decrease trust and generate counterproductive employee behaviors at work (Aryee et al. 2002; Mayer and Gavin 2005). It has been shown that “when individuals perceive an imbalance in the exchange and experience dissatisfaction, trust decreases” (Fulmer and Gelfand 2012, p. 1175); as a result of this, people feel insecure and invest energy in self-protective behaviors and in continually making provision for the possibility of opportunism on the part of others (Limerick and Cunnington 1993). In the absence of trust, “people are increasingly unwilling to take risks, demand greater protections against the possibility of betrayal and increasingly insist on costly sanctioning mechanisms to defend their interests” (Cummings and Bromiley 1996, p. 3–4). Employees are less devoted to working efficiently and become distrusted in their roles by engaging in counterproductive behavior, which is a way to minimize their vulnerability vis-à-vis the employer (Tschannen-Moran and Hoy 2000). Conversely, a favorable social exchange will create trust and encourage the employee to develop favorable reactions towards the organization (Flynn 2005).

Certain case studies have highlighted the role played by trust as a major social exchange mechanism and an antecedent of positive behaviors. In the early 1980s, the executives of Harley Davidson took ownership of the company in order to save it from decline and put in place a new method of management based on trust. The result was astonishing: between 1981 and 1987, annual revenues per employee doubled and productivity rose by 50%.Footnote 1

Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Cynicism

CSR, or a company’s dedication to improving the well-being of society through non-profitable business practices and resource contributions (Kotler and Lee 2005), conveys positive values and may therefore positively influence the general perception of company leaders in the eyes of the employees. This concept is framed around the question put forward by Bowen (1953): “To what extent does the interest of business in the long run merge with the interests of society?” (p. 5), to which he responds that businesspeople are expected to take their businesses forward in such a way that their decisions and policies are congruent with societal norms and customs.

CSR has received increasing attention in the academic literature in recent years. Carroll’s (1979) definition of CSR is one of the most comprehensive and widely accepted of past decades. According to Gond and Crane (2010), “the model of CSP [Corporate Social Performance] by Carroll (1979) appears as a real breakthrough because it purports to organize the coexistence of what were previously conceptualized as rival approaches to the same phenomenon (…) by incorporating economic responsibility as one level of CSR, Carroll’s model of CSP reconciles the debate between some economists’ narrow view of social involvement (Friedman 1970) and the advocates of a broader role for the firm” (p. 682).

Carroll’s model describes the four responsibilities that a business is expected to fulfill, namely economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary.

-

1.

Economic responsibility Society anticipates that a business will successfully generate profit from its goods and services and maintain a competitive position. The aim of establishing businesses was to create economic benefits, as well as products and services, for both shareholders and society. The notion of social responsibility was later incorporated into the execution of business. Managers are liable to adopt those strategies that could generate profit in order to satisfy shareholders. Furthermore, managers are accountable for taking steps toward expanding the business. All the other responsibilities are considered as extensions of economic responsibility, because without it, they have no meaning.

-

2.

Legal responsibility Building upon economic responsibility, a society wants business to follow the rules and regulations of behavior in a community. A business is expected to discharge its economic responsibility by meeting the legal obligations of society. Managers are expected to develop policies that do not violate the rules of that society. In order to comply with the social contract between firm and society, managers are expected to execute business operations within the framework of the law as defined by the state authorities. Legal responsibilities embody the concept of justice in the organization’s functioning. This responsibility is as fundamental to the existence of the business as economic responsibility.

-

3.

Ethical responsibility This type of responsibility denotes acts that are not enforced by the law but that comply with the ethical norms and customs of society. Although legal responsibility encompasses the notion of fairness in business operations, ethical responsibility takes into account those activities that are expected of a business but not enforced by the law. These cannot be described within a boundary, as they keep expanding alongside society’s expectations. This type of responsibility considers the adoption of organizational activities that comply with the norms or concerns of society, provided that shareholders deem them to be in accordance with their moral privileges. Firms find it difficult to deal with these aspects, as ethical responsibilities are usually under public discussion and so not properly defined. It is important to realize that for a company, ethical conduct is a step beyond simply complying with the legal issues.

-

4.

Discretionary responsibility All those self-volunteered acts that are directed towards the improvement of society and have a strategic value rather than having been implemented due to legal or ethical concerns fall under this type of responsibility. Discretionary responsibility encompasses those activities that a business willingly performs in the interests of society, for instance providing funding for students to study, or helping mothers to work by providing a free day-care center. A business should undertake tasks to promote the well-being of society. Discretionary aspects differ from ethical ones in the sense that discretionary acts are not considered in a moral or ethical light. The public has a desire for businesses to endow funds or other assets for the betterment of society, but a business is not judged as unethical if it does not act accordingly.

CSR perceptions influence internal stakeholders’ attitudes (Folger et al. 2005). As Hansen et al. (2011) have stated, “employees not only react to how they are treated by their organization, but also to how others (…) are treated (…). If an employee perceives that his or her organization behaves in a highly socially responsible manner—even toward those outside and apart from the organization, he or she will likely have positive attitudes about the company and work more productively on its behalf” (p. 31).

This might indicate that employees’ perceptions of CSR could potentially reduce undesirable and counterproductive behaviors in the workplace, including employee cynicism. Employee cynicism has greatly increased in recent decades (Mustain 2014), and modern-day organizational realities involve the presence of employee cynicism at work as a response to a violation of employees’ expectations regarding social exchange (Neves 2012), leading to a reduction of discretionary behaviors that go beyond the minimum required (Neves 2012). As illustrated by Motowidlo et al. (1997), extra-role or contextual behavior that goes beyond the minimum task-related required behavior is key to the performance of the organization, as it helps to maintain the positive social and psychological environment in which the ‘technical core’ must function. Therefore, reducing employee cynicism is key for organizations.

Conceptualizations of cynicism have moved beyond earlier trait- and emotion-based perspectives (Cook and Medley 1954) to focus on the construct as an attitude comprising the three dimensions to which we refer above: cognitive, affective, and behavioral (Eagly and Chaiken 1992; Dean et al. 1998): “Organizational cynicism is generally conceptualized as a state variable, distinct from trait-based dispositions such as negativity and trait cynicism” (Bommer et al. 2005, p. 736). Scholars acknowledge the role that dispositional cynicism can play in employee cynicism. For example, Cole et al. (2006) examine the links between psychological hardiness and emotions experienced on the one hand and organizational cynicism on the other, while Andersson (1996) argues that self-esteem and the locus of control may contribute to employee cynicism. Although the literature on cynicism is growing, most studies focus on the general idea of organizational cynicism as an attitude (Cutler 2000; Fleming and Spicer 2003), and on its cognitive dimension in particular (Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly 2003).

However, in addition to the cognitive and affective dimensions of employee cynicism (Dean et al. 1998), the behavioral dimension is an important aspect and has its own relationships with organizational outcomes. Chiaburu et al. (2013) find that, though individual characteristics such as negative affectivity or trait cynicism may enhance employee cynicism, contextual factors such as perceived organizational support, organizational justice, psychological contract violations, and perceived organizational politics are more accurate predictors of employee cynicism and explain its rise. A number of scholars stress the importance of this behavioral dimension of employee cynicism (O’Leary 2003; Naus et al. 2007), which is composed of cynical humor and cynical criticism (Brandes and Das 2006). Brandes and Das (2006) call for more scholarly attention to be paid to it; our aim here is to answer this call.

Dean et al. (1998) describe cynical employees as ones who level strong criticism at the company leaders in a cynical language and tone and decide to reduce discretionary behaviors that go beyond the minimum required (Neves 2012). They define employee cynicism as a tendency to engage in disparaging and critical behavior toward the organization in a way that is consistent with their belief that it lacks integrity. This behavior stems from a feeling of hopelessness and pessimism that spreads as a malaise within groups and undermines work relationships (Kanter and Mirvis 1989). Employees who are organizationally cynical may take a defensive stance, verbally opposing organizational action and mocking organizational initiatives publicly (Dean et al. 1998).

Management needs to intervene to reduce these behaviors at work, but since management is both the source and the target of cynicism, it must reestablish a climate of psychological security by indirect means (Dean et al. 1998; O’Leary 2003). Some scholars posit that certain organizational-level policies or actions can decrease employee cynicism, such as offering a supportive environment, demonstrating fairness, minimizing the violation of psychological contracts, and reducing organizational politics (Chiaburu et al. 2013). CSR can also act as a policy demonstrating the organization’s willingness to engage in socially responsible activity.

Research has shown that psychological contract violations increase cynicism (Pugh et al. 2003; Chrobot-Mason 2003). Individuals develop cynicism towards businesses based on the extent to which they perceive them to exhibit benevolence toward their employees (Bateman et al. 1992). In light of this, CSR may be seen as a factor that can reduce behavioral employee cynicism. By engaging in CSR, company leaders may generate a more positive image of the social exchange with their employees and thus decrease their behavioral tendency toward cynicism. If employees see that their organization is genuinely addressing its social obligations, its honest image will be restored in their eyes and, as a reciprocal response, they will decrease their cynical behavior. According to Carroll (1979), “to fully address the entire range of obligations business has to society, it must embody the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary categories of business performance” (p. 499). If all four dimensions of CSR are perceived to be in place, this could act as a signal of honesty on the company’s part. Each dimension of CSR may therefore have an impact on employees’ behavioral cynicism.

Economic responsibility remains the most important dimension of CSR for big companies (Konrad et al. 2006). A company’s primary goal is to generate a profit. If it does not do this, it can do nothing for its employees.

Compliance with the law may exert the same positive impact. The importance of the legal aspect of CSR has already been measured by Shum and Yam (2011), who compared the four components of Carroll’s construct and found that respondents placed more emphasis on this aspect than any other. This was true regardless of age or occupation; only marketing employees placed a little more focus on economic aspects than legal ones. Although compliance with the law seems an obvious requirement, let us for a moment consider what opinion employees may have of a company that does not exhibit it. Laws have the function of informing about the right behaviors. They stand for the “right thing to do.” For employees, compliance with the law may be perceived as a means of preventing unethical behavior. This is why respect for the law and the spirit of the law are a positive signal that could decrease employees’ cynicism.

The two other dimensions of CSR are voluntary. According to Aguilera et al. (2007), it is these voluntary actions that can actually be considered CSR, and these are probably also the ones that really matter to employees. Employees value the discretionary dimension because it goes beyond compliance with the law and societal expectations. Adams et al. (2001) showed that the ethical dimension is important to them also by revealing that employees of companies with codes of ethics perceive colleagues and superiors as more ethical and feel more supported than employees of companies without such codes.

Consequently, this study aims at answering the following research questions: does behavioral employee cynicism reduce when employees perceive company leaders to be engaging in CSR efforts? And do the four dimensions of CSR play a role in decreasing cynical behavior at work?

Accordingly, we posit the following hypotheses:

H1

The perception of CSR is negatively related to employee cynicism.

-

H1a The economic dimension of CSR is negatively related to employee cynicism.

-

H1b The legal dimension of CSR is negatively related to employee cynicism.

-

H1c The ethical dimension of CSR is negatively related to employee cynicism.

-

H1d The discretional dimension of CSR is negatively related to employee cynicism.

Corporate Social Responsibility, Organizational Trust, and Employee Cynicism

CSR generates the belief among employees that the company has positive intentions and meets the more or less implicit demands of society. From employees’ point of view, CSR conveys positive values and demonstrates a caring stance, thus generating the belief that the company is trustworthy. Prior research suggests that CSR perceptions impact a variety of employee attitudes and behaviors, including trust in organizational leadership (Hansen et al. 2011). CSR becomes a key factor in establishing, maintaining, or improving a good relationship between company leaders and their employees (Persais 2007, McWilliams and Siegel 2001). Meanwhile, Pivato et al. (2008, p. 3) identify trust as the “first result of a firm’s CSR activities.”

Aguilera et al. (2007) provide a theoretical model to explain why business organizations engage in CSR. One of the motives for this is relational: “Relational models show that justice conveys information about the quality of employees’ relationships with management and that these relationships have a strong impact on employees’ sense of identity and self-worth” (p. 842). Trust generation, or an increase in trust, is one of the benefits of CSR (Bustamante 2014).

Many definitions of trust generally present it as involving positive expectations of trustworthiness, a willingness to accept vulnerability, or both (Fulmer and Gelfand 2012). As reported by Rousseau et al. (1998), there is a consensus that risk and interdependence are two necessary conditions for trust to emerge and develop. Trust is the expectation that another individual or group will make an effort of good faith to behave in accordance with commitments (both explicit and implicit), to be honest, and not to take excessive advantage of others even when the opportunity exists (Cummings and Bromiley 1996).

Following Mayer et al. (1995), we define organizational trust as employees’ willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of their employer based on positive expectations about its intentions or behavior. In this definition, the organization is represented by both its top management and its procedures, norms, and decisions. Dirks and Ferrin (2002) consider top management and management in general as representatives of the organization. Since Levinson (1965), it has been acknowledged that employees tend to personify the acts of their organization. Organizational acts and management practices thus become a sign of potential support for and interest in the employees (Guerrero and Herrbach 2009). Employees who perceive the organizational leadership to be acting in its own best interests rather than in those of its employees will deem it to be less trustworthy due to a lack of benevolence (Mayer et al. 1995). As suggested by Fulmer and Gelfand (2012), we clearly identify the trust referent (which refers to the target of the trust) and the trust level (which refers to the level of analysis of the study): in this study, the trust referent is the organizational leadership as a whole (Robinson and Rousseau 1994), while the trust level is the individual’s degree of trust in that referent (Fulmer and Gelfand 2012).

It is difficult to conceive of an organization thriving without trust (Kramer 1999). Without trust, employees struggle to function effectively and cope with their interdependence on each other in a less hierarchical organization (Gilbert and Tang 1998). Trust is likely to influence employee behavior by improving job satisfaction and creativity and reducing anxiety (Cook and Wall 1980). It improves coordination between colleagues (McAllister 1995), allows their interactions to be more honest and freer, and significantly reduces the withholding of information (Zand 1972). Conversely, employees who do not trust their organizational leadership will tend to be defensive—to adopt behaviors that still conform to the organizational rules but that minimize any risk in the relationship.

Because a company that is perceived as socially responsible is generally seen as being honest, perceived CSR-related efforts should exert an impact on organizational trust. Meanwhile, because trust increases the commitment of employees, it may decrease undesirable behavior such as employee cynicism. Researchers have reported that negative attitudes at work, including employee cynicism, are the result of poor social exchange. Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly (2003) examine employee cynicism as a reaction to social exchange violations in the workplace and find that cynicism stems from a breach in or violation of trust, meaning either reneging on specific promises made to the employees or flouting more general expectations within the framework of trust (Andersson 1996; Andersson and Bateman 1997; Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly 2003).

By assuming that trust acts as a mediator between the exchange partners, our model not only observes the relationship between perceptions of CSR and the behavioral dimension of employee cynicism, but also provides an explanation of the psychological process underlying this relationship. This psychological process involves the reduction of negative behavior (employee cynicism) through a positive attitude (increased trust) as predicted by the organization’s application of CSR policies.

Based on the above, we hypothesize that the perception of CSR may impact trust, which, in turn, will decrease cynicism:

H2

Organizational trust mediates the relationship between CSR and employee cynicism.

-

H2a Organizational trust mediates the relationship between economic CSR and employee cynicism.

-

H2b Organizational trust mediates the relationship between legal CSR and employee cynicism.

-

H2c Organizational trust mediates the relationship between ethical CSR and employee cynicism.

-

H2d Organizational trust mediates the relationship between discretional CSR and employee cynicism.

Proposed Model

Method

Procedure and Participants

An online survey was sent to a sample of 620 in-company employees. The database used comprises all the personal and professional contacts of one of the authors. This author is in charge of an MBA programme at a major French university and most of the respondents (70%) are alumni with whom she periodically has contact. In order to obtain a high response rate, she sent a personal message to each of them explaining the importance of their response and that the responses would be anonymous. She also sent a reminder email to those who did not answer the first time. The method yielded a 65% response rate (N = 403) and covered a wide range of occupations. 70% of the participants were male and 30% female. 90% of the participants were European, 8% American, and 2% Asian. The majority of participants (60%) identified themselves as supervisors. Finally, the participants’ average age was 38 years and most of the respondents had worked for their company for between 2 and 5 years. There were no missing values in the data since the survey was administered online and the respondents were prompted for any questions which they did not answer. Cook’s and Leverage method was used to check for any multivariate outliers, which resulted in the removal of 59 observations.

Measures

Items of all measures were scored on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

All four dimensions of the CSR construct (economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary) were measured using the scales developed by Maignan et al. (1999) and adapted for the study. Studies report that this instrument has satisfactory psychometric properties, including its construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Maignan and Ferrell 2000). The four items for the economic dimension of CSR (α = 0.70) are “My company has a procedure in place to respond to every customer complaint,” “My company continually improves the quality of our products,” “My company uses customer satisfaction as an indicator of its business performance,” and “Top management establishes long-term strategies for our business.” The four items for the legal dimension of CSR (α = 0.75) are “Managers of my company are informed about the relevant environmental laws,” “All our products meet legal standards,” “Managers of my organization try to comply with the law,” and “My company seeks to comply with all laws regulating hiring and employee benefits.” The four items for the ethical dimension of CSR (α = 0.77) are “My company has a comprehensive code of conduct,” “Members of my organization follow professional standards,” “Top managers monitor the potential negative impacts of our activities on our community,” and “A confidential procedure is in place for employees to report any misconduct at work (such as stealing or sexual harassment).” The four items for the discretionary dimension of CSR (α = 0.81) are “My company encourages employees to join civic organizations that support our community,” “My company gives adequate contributions to charities,” “My company encourages partnerships with local business and schools,” and “My company supports local sports and cultural activities.”

Concerning organizational trust, responses were coded such that a high score would indicate a high degree of trust in one’s employer. Trust was measured using the four items that focus on trust in the organization of the Organizational Trust Inventory’s short form developed by Cummings and Bromiley (1996) and adapted for the present study. The four items (α = 0.93) are “I globally trust my company,” “I think that my company shows integrity,” “I feel I can definitely trust my company,” and “My company cares about the employees.”

Employee cynicism was measured using the behavioral dimension (cynical criticism) of the scale developed by Brandes et al. (1999). The behavioral component of employee cynicism relates to the practice of making harmful statements about the organization. The four items (α = 0.70) are all reverse-scored: “I do not complain about company matters,” “I do not find faults with what the company is doing,” “I do not make companyrelated problems bigger than they actually are,” and “I focus on the positive aspects of the company rather than just focusing on the negative aspects.”

We controlled for company size and demographic variables such as the respondents’ age and position, as these variables can function as potential individual antecedents to specific attitudes at work (Hess and Jepsen 2009; Peterson et al. 2001; Twenge and Campbell 2008).

After suppressing missing values and outliers, the sample comprised 366 respondents. To assess the discriminant validities, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for all six variables. Following this, we employed the approach of Henseler et al. (2015), who argue that other techniques such as the Fornell-Larcker criterion and the assessment of cross-loadings are less sensitive methods and unable to detect a lack of discriminant validity successfully. They suggest a more rigorous approach based on the comparison of heterotrait–heteromethod and monotrait–heteromethod (HTMT) correlations. Hence, we applied the HTMT criterion to all constructs and the Table 1 shows all values in the acceptable range—which should be < 0.85—as suggested by Henseler et al. (2015).

The results show that the six-factor model fits the data well (χ2 = 487.73, χ2/df = 2.06, RMSEA = 0.05, CFI = 0.94, TLI = 0.93 and SRMR = 0.05). CLI and TFI scores above 0.90 and SMRM and RMSEA scores below 0.07 are judged to confirm a good fitting model (Hair et al. 2010).

Both procedural and statistical methods were used to control for common method variance (CMV) (Spector 1994). First, since the data were collected through an online survey, a question randomization option was used that showed questions to each respondent in a shuffled manner. Second, Harman’s one-factor test was conducted with an unrotated factor solution. The test revealed an explained variance of 27.5%, well below the threshold of 50% suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003). Harman’s single factor was also run using CFA. According to Malhotra et al. (2006, p. 1867), “method biases are assumed to be substantial if the hypothesized model fits the data.” Our single-factor model showed a poor data fit (GFI = 0.704; AGFI = 0.648; NFI = 0.639; IFI = 0.685; TLI = 0.652; RMR = 0.104 and RMSEA = 0.113), which confirms the non-existence of CMV. Finally, we used a common latent factor (CLF) test and compared the standardized regression weights of all items for models with and without CLF. The differences in these regression weights were found to be very small (< 0.200) which confirmed that CMV is not a major issue in our data (Gaski 2017). Factor scores were saved for each of the six variables and were further used in path analysis for mediation.

Inspection of the variance inflation factor scores indicates that there are no instances of multicollinearity among any of the variables (the largest variance inflation factor is 2.2).

Analysis and Results

Table 2 reports the means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlation coefficients for each of the variables in this study. Cronbach’s alpha values are listed in the diagonal and range from 0.70 to 0.93.

Path analysis was run to test the direct and indirect effects of CSR dimensions on employee cynicism via trust. First, a path analysis model with direct relationships between CSR and employee cynicism was run. The results showed that two of the dimensions [economic (β = − 0.125; p = 0.034) and discretionary (β = − 0.167; p = 0.009) responsibility] of CSR had significant negative direct relationships with employee cynicism while the relationships of the other two dimensions [legal (β = − 0.087; p = 0.164) and ethical (β = − 0.119; p = 0.056) responsibility] were found to be insignificant. Table 3 represents the results of hypotheses H1a–H1d which shows that H1a and H1d were supported, whereas H1b and H1c were not supported.

Even though two of the direct paths were not found significant (legal and ethical) in our total effects model, these analyses were deemed appropriate. Considering that a simple regression equation for the total effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable (X → Y) may yield a non-significant effect, e.g., due to suppression and confounding effects (MacKinnon et al. 2000), researchers are not required to establish a significant total effect before proceeding with test of indirect effects (Hayes 2009).

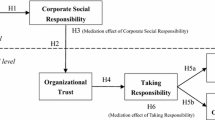

Therefore, a mediation model was run in which trust was incorporated as the mediating variable. To test the model, we used bootstrapping samples (Preacher and Hayes 2008). When trust was included in the model, none of the CSR dimensions had a direct effect on employee cynicism; therefore, we removed all the insignificant paths to reach an optimal model (shown in Fig. 1) with good fit indices.

Since two of the direct paths (economic and discretionary responsibilities) were found significant in the direct effects model, we compared the full mediation model to two alternative models. In the first alternative model (ALT1), a direct path from economic responsibility to cynicism was included, while in the second alternative model (ALT2) a direct path from discretionary responsibility to cynicism was included. The model fit indices of all compared models are presented in Table 4. The full mediation model fits the data well in comparison to the alternate models as no significant difference in the alternate models was found using Chi-square difference tests. Hair et al. (2010) suggest, for a model with a difference of 1 degree of freedom, a Δ χ2 of 3.84 or higher would be significant at 0.05 level. Hence, the full-mediation model was retained with only the significant paths. The following fit indices were used to determine model adequacy and were all in the acceptable range: CMIN/df = 1.547; Tucker–Lewis index = 0.986; comparative fit index = 0.996; root-mean square error of approximation: 0.040; standardized root-mean-square residual: 0.0276.

Based on the full mediation model, it can be concluded that all four CSR variables were found to have an indirect negative effect on employee cynicism mediated by employee trust—also referred as intervening variable.Footnote 2 More specifically, each indirect effect was significant as the lower level and upper level confidence interval did not include zero. A summary of the results is shown in Table 5.

H2, positing mediation, was tested with the bootstrapping resampling method. Following recommended procedures (Preacher and Hayes 2008; Cheung and Lau 2008), we used the bias-corrected bootstrapping method to create the resample using 95% confidence intervals. H2, proposing organizational trust as a mediator of the CSR–employee cynicism relationship, is supported for the four CSR dimensions. Thus, the negative relationship between CSR and employee cynicism is explained by employee trust in the organization. With regard to employee cynicism, the indirect effect of the economic dimension was − 0.055 (LL = − 0.09 to UL = − 0.01), that of the legal dimension was − 0.113 (LL = − 0.15 to UL = − 0.06), that of the ethical dimension was − 0.122 (LL = − 0.17 to UL = − 0.07), and that of the discretionary dimension was − 0.102 (LL = − 0.15 to UL = − 0.05). Overall, the explained variance for the dependent variable cynicism was found to be 20%.

Discussion

The objective of this paper was to test a model for how CSR influences employee cynicism via the mediating role of organizational trust. The study illustrates that perceived CSR activities decrease counterproductive behaviors such as employee cynicism with the help of trust. In line with previous research, our study shows that employees’ perceptions of their organization’s CSR and their organizational leaders’ commitment to it influence their behavior at work (Folger et al. 2005; Hansen et al. 2011; Rupp et al. 2006) and affect their level of cynicism in particular (Evans et al. 2011). We demonstrate that:

-

1.

Some dimensions of CSR are negatively related to employee cynicism.

-

2.

Each of the four dimensions of CSR significantly impact trust in the organization, which in turn reduces employee cynicism.

We identify the construct of employee cynicism as a negative behavior in organizations whereby employees tend to engage in disparaging and critical behavior consistent with the belief that the organization and its leaders lack integrity (Dean et al. 1998; Brandes and Das 2006). The belief that the organization lacks integrity (Andersson 1996; Dean et al. 1998; Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly 2003) and the perception of psychological contract violations (Pugh et al. 2003; Chrobot-Mason 2003; Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly 2003) are the main factors in employee cynicism. Our results suggest that if employees perceive CSR policies to be applied consistently at the organizational level, criticism and witticisms from organizationally cynical employees will be reduced, as such policies help them believe that their organization exhibits integrity. Perceived CSR policies thus help prevent employees from seeing the organization’s behavior as purely self-interested (Andersson 1996; Neves 2012).

The direct negative link between CSR perception and employee cynicism is validated for the economic and discretionary dimensions.

In our sample, the economic dimension has a significate negative impact on cynicism. This may be due to the fact that the generation of profits by companies directly benefits employees, through incentive bonuses and because their bargaining power increases with the company’s profit margins. More satisfied employees are less likely to be cynical. This result seems to contradict Herzberg’s (1987) motivation theory, according to which economic factors cannot satisfy employees. This may be due to the fact that our sample is French. In France, because the unemployment rate is high (9%), having a well-paid job may indeed be enough of a motivating factor to decrease cynical behavior.

The legal dimension has no direct impact on cynicism. In our sample, the respondents do not value strict compliance with the law. Since they are well aware of practices such as tax optimization, they know that being legal does not always mean being ethical.

The impact of the ethical dimension exists but its significance is very weak, which demonstrates that employees’ expectations of their organization and leaders go well beyond economic results and compliance with rules and procedures.

The discretionary dimension has a significate negative impact on cynicism. It shows that there is “no inherent contradiction between improving competitive context and making a sincere commitment to bettering society” (Porter and Kramer 2002, p. 16). On seeing their company’s commitment to the well-being of society, the employees in our sample decrease their potential counterproductive behaviors.

Another contribution of this paper is to emphasize the impact of perceived CSR through all four of its dimensions (economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary) on employees’ behavior via trust. This is consistent with Carroll’s (1979) primary aim, namely to reconcile businesses’ responsibility to make a profit, with its other responsibilities (to be law-abiding, ethically oriented, and socially supportive). This empirical result is new to the literature: although a link between economic performance and CSR had been theoretically identified by many scholars (Carroll 1979; Wartick and Cochran 1985), previous empirical findings reported a negative correlation between the economic dimension and all the other dimensions of responsibility (Aupperle et al. 1983). In our sample, employees feel a greater sense of trust in firms that are able to respond to their primary economic responsibility. Our empirical evidence may differ due to the current climate: since the economic crisis, respondents have required their organizations to perform well economically in order to sustain economic growth and employment while simultaneously taking care of the stakeholders weakened by the current crisis.

The impact of the legal dimension on organizational trust shows the extent to which individuals tend to assess what they consider to be fair and right in a subjective manner rather than by applying an objective principle of justice imposed by rules or institutions (James 1993). Compliance with procedures and rules can thus be viewed as a heuristic gauge that people use to evaluate the trustworthy nature of the company’s responsibility and leadership.

The impact of the ethical dimension on organizational trust, which is the most significant of the four, demonstrates employees infer information about their leaders’ ethics based on what they can observe, such as perceptions about CSR activity (Hansen et al. 2016). These results concur with those of Bews and Rossouw (2002), Brown et al. (2005) and Xu et al. (2016), which suggest that genuine ethical managerial conduct enhances managers’ trustworthiness, and with those of Mo and Shi (2017), who found that the relationships between ethical leadership and employees’ work outcome of deviant behavior were significantly mediated by trust in leaders.

Concerning the discretionary dimension, our study demonstrates that employees consider that a company supporting external stakeholders will potentially support internal ones (Rupp et al. 2006), and philanthropic expenditure may lead stakeholders (including internal ones) to form more positive impressions of an organization and its leaders’ integrity and trustworthiness (Brammer and Millington 2005).

Combining the literatures on CSR and trust offers a deeper understanding of the social exchange mechanisms at work as well as the motivational processes that push employees to engage in counterproductive behaviors. Employees see CSR activities as a sign of the organizational leadership intentions and use these to form an opinion about its trustworthiness. If the company is perceived as making a positive contribution to society (Gond and Crane 2010), employees will infer that its intentions are good and will therefore consider it to be trustworthy, as trust is a key attribute when determining employees’ perceptions of top management’s ethics (Brown et al. 2005). Their likelihood of being cynical will consequently decrease.

This result is consistent with several studies that find perceived measures of corporate citizenship to predict positive work-related attitudes such as organizational commitment (Peterson 2004) and organizational citizenship behavior (Hansen et al. 2011), while reducing employee turnover intentions (Hansen et al. 2011).

The results of our empirical study also confirm those in previous research that establish a link between organizational trust and reactions to the organization and its leaders (Aryee et al. 2002; Dirks and Ferrin 2002; Mayer and Gavin 2005). The impact of perceived CSR on organizational trust shows that CSR has a clear corporate-level benefit. In other words, taking collective interests as a target can generate benefits at the corporate level. In particular, we have confirmed that organizational trust plays a fully fledged mediating role between perceptions of CSR (in all four of its dimensions) and cynical behavior at work. Like former research that has shown that the implementation of a number of management practices such as employee participation practices, communication, empowerment, compensation, and justice is likely to encourage a sense of trust in the organizational leadership (Miles and Ritchie 1971; Nyhan 1999), this paper shows that CSR boosts the employees’ belief in their company’s trustworthiness, which in turn increases trust. This leads them to be more open to the prospect of appearing vulnerable to the company and to its leaders.

In addition, previous studies have shown that organizational trust acts as a partial mediator between employees’ perceptions of CSR and work-related outcomes (Hansen et al. 2011). Our findings show that all four dimensions of CSR (economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary) have an effect on employee cynicism and that this is fully mediated by organizational trust. The four dimensions of CSR seem to signal to the employees that the company and the leadership will treat internal stakeholders as fairly as they treat other external stakeholders, such as shareholders or local communities (Rupp et al. 2006). The mediation of trust is consistent with Hansen et al. (2011, p. 33), for whom “trust is the immediate or most proximate outcome of CSR activity.”

These findings are in line with the growing body of research about the impact of CSR on consumer trust and the intention to buy (Pivato et al. 2008; Castaldo et al. 2009; Du et al. 2011; Park et al. 2014; Swaen and Chumpitaz 2008). The basic contention of this body of research is that the primary outcome of CSR activities is to create trust among consumers and that this trust influences consumers’ buying intentions. We show that the same applies to employees: CSR directly influences trust, which in turn negatively influences cynicism.

To conclude, this study offers insights into the dynamics underlying internal value creation based on CSR. The results of the study show that leadership that visibly promotes and enacts CSR activities will impact employees’ behavior towards the company and its leadership.

Limitations and Future Directions

The study has explored the relationship between employees’ perceptions of CSR and their cynical behavior at work. Our research design involved a survey of a large sample of managers. This method may convey a respondent rationalization bias. Thus, future research should study whether employee cynicism can be reduced by an increased belief in corporate trustworthiness via CSR efforts using an experimental design that better captures respondents’ actual behavior.

As posited by Dean et al. (1998), employee cynicism is an attitude composed of the three attitudinal dimensions of cognition, emotion, and conation. Following research by Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly (2003), Naus et al. (2007), and Brandes and Das (2006), this study measured solely the conative dimension of the cynical attitude in order to focus exclusively on employee behavior. Future research should measure the overall attitude of cynicism, which would broaden our understanding of how perceived CSR affects employee reactions at work.

A number of lines of future research inquiry could complement this study. As we focused here on an organizational-level referent, future studies should explore the role of stakeholders in the employees’ immediate environment, such as supervisors, colleagues, and peers (Whitener et al. 1998). Lewicki et al. (2005) have shown, for instance, that trust in one’s supervisor plays a central role in mediating the effects of interactional justice on attitudes and behaviors at work.

Temporality (Barbalet 1996) is another variable that may play a significant role in a social exchange relationship linking trust with other variables. While this research presents a social exchange context that assumes a temporal dimension, it overlooks evidence of the duration of the employee–organization relationship.

The role of perceived external prestige should also be investigated (Herrbach et al. 2004). CSR activities may influence employees’ beliefs about how outsiders judge their organization’s status and image, meaning that such an external source of information could also impact their trust in the organization and their cynical behavior at work. Should employees receive negative information from the external environment about their organization, they might react to this by developing cynicism in order to align their assessment of the organization with that of outsiders (Frandsen 2012).

This being said, this study opens the door to a variety of organizational-level ways to reduce employee cynicism by pursuing different CSR activities in a genuine manner, which range from enhancing economic performance and complying with the law to developing an ethical posture and supporting the community, all of which increase organizational trust.

Notes

References

Adams, J., Tashchian, A., & Shore, T. (2001). Codes of ethics as signals for ethical behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(3), 199–211.

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38(4), 932–968.

Ajzen, I. (2001). Nature and operation of attitudes. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 27–58.

Albrecht, S. L. (2002). Perceptions of integrity, competence and trust in senior management as determinants of cynicism toward change. Public Administration & Management, 7(4), 320–343.

Andersson, L. (1996). Employee cynicism: An examination using a contract violation framework. Human Relations, 49(11), 1395–1418.

Andersson, L. M., & Bateman, T. S. (1997). Cynicism in the workplace: Some causes and effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 8(5), 449–469.

Aryee, S., Budhwar, P. S., & Chen, Z. X. (2002). Trust as a mediator of the relationship between organizational justice and work outcomes: Test of a social exchange model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(3), 267–285.

Aupperle, K., Hatfield, J., & Carroll, A. (1983). Instrument development and application in CSR. Academy of Management Proceedings, 369–373.

Barbalet, J. M. (1996). Social emotions: Confidence, trust and loyalty. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 16(9/10), 75–96.

Bateman, T., Sakano, T., & Fujita, M. (1992). Roger, me, and my attitude: Film propaganda and cynicism toward corporate leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 768–771.

Bews, N. F., & Rossouw, G. J. (2002). A role for business ethics in facilitating trustworthiness. Journal of Business Ethics, 39(4), 377–390.

Bommer, W. H., Rich, G. A., & Rubin, R. S. (2005). Changing attitudes about change: Longitudinal effects of transformational leader behavior on employee cynicism about organizational change. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(7), 733–753.

Bowen, H. R. (1953). Social responsibilities of the businessman. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2005). Corporate reputation and philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 61, 29–44.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporation social responsibility to organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701–1719.

Brandes, P., & Das, D. (2006). Locating behavioral cynicism at work: Construct issues and performance implications. In P. L. Perrewé & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Employee health, coping and methodologies (research in occupational stress and well-being) (Vol. 5, pp. 233–266). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Brandes, P., Dharwadkar, R., & Dean, J. W. (1999). Does organizational cynicism matter? Employee and supervisor perspectives on work outcomes. In Proceedings of the 36th annual meeting of the Eastern Academy of Management, Philadelphia.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Bustamante, S. (2014). CSR, trust and the employer brand, CSR trends. In J. Reichel (Ed.), Beyond business as usual. Łódź: CSR Impact.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Castaldo, S., Perrini, F., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2009). The missing link between corporate social responsibility and consumer trust: The case of fair trade products. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(19), 1–15.

Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2008). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 296–325.

Chiaburu, D. S., Peng, A. C., Oh, I., Banks, G. C., & Lomelie, L. C. (2013). Antecedents and consequences of employee organizational cynicism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(2), 181–197.

Chrobot-Mason, D. L. (2003). Keeping the promise: Psychological contract violations for minority employees. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(1), 22–45.

Cole, M. S., Bruch, H., & Vogel, B. (2006). Emotion as mediators of the relations between perceived supervisor support and psychological hardiness on employee cynicism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(4), 463–484.

Cook, J., & Wall, T. (1980). New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfilment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53(1), 39–52.

Cook, W. W., & Medley, D. M. (1954). Proposed hostility and pharisaic-virtue scales for the MMPI. Journal of Applied Psychology, 38, 414–448.

Coyle-Shapiro, J., & Conway, N. (2004). The employment relationship through the lens of social exchange. In J. Coyle-Shapiro, L. Shore, S. Taylor & L. Tetrick (Eds.), The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives (pp. 5–28). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900.

Cummings, L. L., & Bromiley, P. (1996). The occupational trust inventory (OTI): Development and validation. In R. Kramer & T. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organizations (pp. 302–330). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Cutler, I. (2000). The cynical manager. Management Learning, 31(3), 295–312.

Dean, J. W., Brandes, P., & Dharwadkar, R. (1998). Organizational cynicism. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 341–352.

Dirks, K., & Ferrin, D. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 611–628.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sankar, S. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: Overcoming the trust barrier. Management Science, 57(9), 1528–1545.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1992). The psychology of attitudes. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Janovich.

Eisenberger, R., Armeli, S., Rexwinkel, B., Lynch, B., & Rhoades, L. (2001). Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 42–51.

El Akremi, A., Gond, J.-P., Swaen, V., de Roeck, K., & Igalens, J. (2015). How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. Journal of Management, 0149206315569311.

Evans, W. R., Goodman, J. M., & Davis, D. D. (2011). The impact of perceived corporate citizenship on organizational cynicism, OCB, and employee deviance. Human Performance, 24, 79–97.

Farooq, M., Farooq, O., & Jasimuddin, S. M. (2014). Employees response to corporate social responsibility: Exploring the role of employees collectivist orientation. European Management Journal, 32, 916–927.

Fleming, P., & Spicer, A. (2003). Working at a cynical distance: Implications for the power, subjectivity and resistance. Organisation, 10(1), 157–179.

Flynn, F. J. (2005). Identity orientations and forms of social exchange in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 30(4), 737–750.

Folger, R., Cropanzano, R., & Goldman, B. (2005). What is the relationship between justice and morality? In J. Greenberg & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (pp. 215–245). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fonseca, L., Ramos, A., Rosa, Á, Braga, A. C., & Sampaio, P. (2012). Impact of social responsibility programmes in stakeholder satisfaction: An empirical study of portuguese managers’ perceptions. Journal of US-China Public Administration, 9(5), 586–590.

Frandsen, S. (2012). Organizational image, identification, and cynical distance: Prestigious professionals in a low-prestige organization. Management Communication Quarterly, 26, 351–376.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits (pp. 122–126). New York: New York Times.

Fulmer, C. A., & Gelfand, M. J. (2012). At what level (and in whom) we trust: Trust across multiple organizational levels. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1167–1230.

Gaski, J. (2017). Common latent factor: Confirmatory factory analysis. Accessed March 15, 2018, from http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com/index.php?title=Confirmatory_Factor_Analysis&redirect=no#Common_Latent_Factor.

Gilbert, J. A., & Tang, T. L. P. (1998). An examination of organizational trust antecedents. Public Personnel Management, 27(3), 321–338.

Glavas, A., & Godwin, L. (2013). Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. Journal Business Ethics, 114, 15–27.

Gond, J.-P., & Crane, A. (2010). Corporate social performance disoriented: Saving the lost paradigm? Business and Society, 49(4), 677–703.

Guerrero, S., & Herrbach, O. (2009). Organizational trust and social exchange: What if taking good care of employees were profitable? Industrial Relations, 64(1), 6–27.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010) Multivariate data analysis, 7th edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hansen, S. D., Alge, B. J., Brown, M. E., Jackson, C. L., & Dunford, B. B. (2013). Ethical leadership: Assessing the value of a multifoci social exchange perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 115, 435–449.

Hansen, S. D., Dunford, B. B., Alge, B. J., & Jackson, C. L. (2016). Corporate social responsibility, ethical leadership, and trust propensity: A multi-experience model of perceived ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 137, 649–662.

Hansen, S. D., Dunford, B. B., Boss, A. D., Boss, R. W., & Angermeier, I. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 29–45.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

Herrbach, O., Mignonac, K., & Gatignon, A. L. (2004). Exploring the role of perceived external prestige in managers’ turnover intentions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 15(8), 1390–1407.

Herzberg, F. (1987). One more time: How do you motivate employees? (pp. 5–16). Boston: Harvard Business Review.

Hess, N., & Jepsen, D. M. (2009). Career stage and generational differences in psychological contracts. Career Development International, 14(3), 261–283.

James, K. (1993). The social context of organizational justice: Cultural, intergroup, and structural effects on justice behaviors and perceptions. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace: Approaching fairness inhuman resources management (pp. 21–50). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Johnson, J., & O’Leary-Kelly, A. (2003). The effects of psychological contract breach and organizational cynicism: Not all social exchange violations are created equal. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 627–647.

Kanter, D., & Mirvis, P. (1989). The cynical Americans: Living and working in an age of discontent and disillusion. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Konrad, A., Steurer, R., Langer, M. E., & Martinuzzi, A. (2006). Empirical findings on business-society relations in Europe. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(1), 89–105.

Kotler, P., & Lee, N. (2005). Corporate social responsibility: Doing the most good for your company and your cause. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: Emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 569–598.

Levinson, H. (1965). Reciprocation: The relationship between man and organization. Administrative Science Quarterly, 9, 370–390.

Lewicki, R. J., Wiethoff, C., & Tomlinson, E. C. (2005). What is the role of trust in organizational justice? In Handbook of organizational justice (247–270). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Limerick, D., & Cunnington, B. (1993). Managing the new organisation: A blueprint for networks and strategic alliances. Chatswood: Business and Professional Publishing.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70, 1–18.

MacKinnon, D. P., Krull, J. L., & Lockwood, C. M. (2000). Equivalence of the mediation, confounding, and suppression effect. Prevention Science, 1, 173–181.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2000). Measuring corporate citizenship in two countries: The case of the United States and France. Journal of Business Ethics, 23(3), 283–297.

Maignan, I., Ferrell, O. C., & Hult, G. T. M. (1999). Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(4), 455–469.

Malhotra, N. K., Kim, S. S., & Patil, A. (2006). Common method variance in IS research: A comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Management Science, 52(12), 1865–1883.

Mathieu, J. E., & Taylor, S. R. (2006). Clarifying conditions and decision points for mediational type inferences in organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 1031–1056.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734.

Mayer, R. C., & Gavin, M. B. (2005). Trust in management and performance: Who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss? Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 874–888.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect-and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 24–59.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117–127.

Miles, R. E., & Ritchie, J. B. (1971). Participative management: Quality vs. quantity. California Management Review, 13, 48–56.

Mo, S., & Shi, J. (2017). Linking ethical leadership to employee burnout, workplace deviance and performance: Testing the mediating roles of trust in leader and surface acting. Journal of Business Ethics, 144, 293–303.

Morgeson, F. P., Aguinis, H., Waldman, D. A., Siegel, D. S. (2013). Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future. Personnel Psychology, 66, 805–824.

Motowidlo, S., Borman, W., & Schmit, M. (1997). A theory of individual differences in task and contextual performance. Human Performance, 10(2), 71–83.

Mustain, M. (2014). Overcoming cynicism: William James and the metaphysics of engagement. New York: Continuum Publishing Corporation.

Naus, F., Van Iterson, A., & Roe, R. (2007). Organizational cynicism: Extending the exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect model of employees’ responses to adverse conditions in the workplace. Human Relations, 60(5), 683–718.

Neves, P. (2012). Organizational cynicism: Spillover effects on supervisor–subordinate relationships and performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 23, 965–976.

Nyhan, R. C. (1999). Increasing affective organizational commitment in public organizations: The key role of interpersonal trust. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 19, 58–70.

O’Leary, M. (2003). From paternalism to cynicism: Narratives of a newspaper company. Human Relations, 56(6), 685–704.

Osveh, E., Singaravello, K., & Boerhannoeddin, A. (2015). Linkage between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Mediation effect of organizational identification. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 5(3), 174–190.

Özler, D. E., Atalay, C. (2011). A research to determine the relationship between organizational cynicism and burnout levels of employees in health sector. Business and Management Review, 1(4), 26–38.

Park, J., Lee, H., & Kim, C. (2014). Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. Journal of Business Research, 67(3), 295–302.

Persais, E. (2007). La RSE est-elle une question de convention? Revue Française de Gestion, 172(3), 79–97.

Peterson, D. (2004). The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Business and Society, 43(3), 296–319.

Peterson, D., Rhoads, A., & Vaught, B. C. (2001). Ethical beliefs of business professionals: A study of gender, age and external factors. Journal of Business, 31(3), 225–232.

Pivato, S., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2008). The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: The case of organic food. Business Ethics: A European Review, 17, 3–12.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2002). The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harvard Business Review, 80(12), 56–68.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Preston, M. (2014). Business success beyond the short term: CEO perspectives on sustainability. In 17th annual global CEO survey summary: sustainability, CEO survey insights.

Pugh, S. D., Skarlicki, D. P., & Passell, B. S. (2003). After the fall: Layoff victims’ trust and cynicism in re-employment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(2), 201–212.

Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(3), 245–259.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A crossdiscipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 393–404.

Rupp, D. E., Ganapathi, J., Aguilera, R. V., & Williams, C. A. (2006). Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 537–543.

Schuler, D. A., & Cording, M. (2006). A corporate social performance–corporate financial performance behavioral model for consumers. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 540–558.

Settoon, R. P., Bennett, N., & Liden, R. C. (1996). Social exchange in organizations: Perceived organizational support, leader-member exchange, and employee reciprocity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(3), 219–227.

Shum, P. K., & Yam, S. L. (2011). Ethics and law: Guiding the invisible hand to correct corporate social responsibility externalities. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(4), 549–571.

Spector, P. E. (1994). Using self-report questions in OB research: A comment on the use of a controversial method. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 385–392.

Swaen, V., & Chumpitaz, R. C. (2008). Impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust. Recherche et Applications en Marketing (English Edition), 23(4), 7–34.

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, W. K. (2000). A multidisciplinary analysis of the nature, meaning, and measurement of trust. Review of Educational Research, 70(4), 547–593.

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, S. M. (2008). Generational differences in psychological traits and their impact on the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(8), 862–877.

Wartick, S. L., & Cochran, P. L. (1985). The evolution of the corporate social performance model. Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 758–769.

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 40(1), 82–111.

Whitener, E. M., Brodt, S. E., Korsgaard, M. A., & Werner, J. M. (1998). Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 513–530.

Xu, A. J., Loi, R., & Ngo, H. (2016). Ethical leadership behavior and employee justice perceptions: The mediating role of trust in organization. Journal of Business Ethics, 134, 493–504.

Zand, D. E. (1972). Trust and managerial problem solving. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(2), 229–239.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author A declares that he/she has no conflict of interest. Author B declares that he/she has no conflict of interest. Author C declares that he/she has no conflict of interest. Author D declares that he/she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study that involved human participants were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Serrano Archimi, C., Reynaud, E., Yasin, H.M. et al. How Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility Affects Employee Cynicism: The Mediating Role of Organizational Trust. J Bus Ethics 151, 907–921 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3882-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3882-6