Abstract

This paper addresses the issue of the influence of global governance institutions, particularly international sustainability standards, on a firm’s intra-organizational practices. More precisely, we provide an exploratory empirical view of the impact of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) on a multinational corporation’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) management practices. We investigate standard compliance by comparing the stated intention of the use of the GRI with its actual use and the consequent effects within the firm. Based on an in-depth case study, our findings illustrate the processes and consequences of the translation of the GRI within the organization. We show that substantive standard adoption can lead to unintended consequences on CSR management practices; specifically it can influence the management structure and CSR committee function; the choice of CSR activities, the relationships between subsidiaries, the temporal dimension of CSR management and the interpretation of CSR performance. We also highlight the need to look at the relationship dynamics (or lack of) between standards. Finally, we illustrate and discuss the role of reporting and its influence on management in order to better understand the internal issues arising from compliance with standards.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

How do corporations comply with international sustainability standards? The last two decades have witnessed a proliferation of new global governance institutions, characterised by non-legal forms of regulation, increasing the pressure on corporations to take into account their social and environmental impacts (Bartley 2007; Gilbert et al. 2011). Within this changing global landscape, a new set of standards [e.g., the UN Global Compact, the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)] have emerged to help corporations implement, manage and report their corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities (Waddock 2008). Those standards can basically be defined as voluntary, commonly used, and specific sets of rules (Brunsson et al. 2012). Firms face increasing societal pressures to adopt such standards and there are extant studies which have provided some empirical evidence on their extensive adoption across corporations (e.g., Arevalo et al. 2013; Delmas and Montes-Sanchos 2011). However, little is known about the trajectory of such standards within organizations and their influence on intra-organizational practices (Heras-Saizarbitoria and Boiral 2013). Recent research has shown that the adoption of standards does not necessarily lead to greater accountability (Behnam and MacLean 2011), as many firms receive certification despite not implementing the standards’ requirements (Aravind and Christmann 2011). Indeed, the voluntary nature of the emergent standards leaves corporations with some freedom to interpret and engage in certain practices (Clapp 2005). It is therefore interesting to examine how standards (in this case the GRI), are used in day-to-day activities by managers (Slager et al. 2012) to develop an understanding of their influence on intra-organizational management practices.

There is also a lack of research on the processes through which reporting influences CSR management (Adams and Frost 2008; Gond and Herrbach 2006). Recently, CSR reporting has become an increasingly important issue for both practitioners and academics. According to KPMG (2011, p. 6), 95 % of the 250 largest companies in the world (based on the Fortune Global 500 ranking) produced a CSR report in 2011, a 14 % increase from 2008. As CSR reporting is becoming effectively mandatory for large multinational corporations (MNCs), it has attracted a considerable amount of academic literature (e.g., Kolk 2008; Sotorrío and Sánchez 2010). Typically, many of these studies offer cross-national comparisons of CSR reporting (e.g., Fortanier et al. 2011; Maignan and Ralston, 2002). However, little attention has been paid to the internal dynamics of reporting and the influence of the GRI inside firms (Fortanier et al. 2011).

This study contributes to a growing literature on the standardisation of CSR (e.g., Haack et al. 2012; Perez-Batres et al. 2012; Slager et al. 2012), by providing an empirical view on the actual use of sustainability standards inside a firm with an emphasis on the micro-level processes of standard compliance. More precisely, we examine the effects of GRI adoption on an MNC’s management practices by comparing the intended and actual applications of the GRI guidelines and their consequent effects on organizational processes. Our analysis is based on a qualitative-embedded case study (Yin 2009) conducted in a North American MNC (North Co.Footnote 1). Our case study is derived from an 18-month investigation of the firm’s CSR practices during which we collected data from multiple primary and secondary sources including interviews, recorded observations of meetings and conference calls, internal documentation as well as the firm’s CSR reports. Our primary data were compared with the GRI guidelines in order to understand the discrepancies between their intended and actual use. In our analysis, we explore the question of: “how does a macro-level institution such as the GRI, influence micro-level CSR organizational practices?” In order to analyse the actual use of the GRI guidelines in an MNC, we draw on a range of literatures, including work on standardization (e.g., Behnam and MacLean 2011; Boiral 2012; Slager et al. 2012), CSR reporting (e.g., Adams and Frost 2008; Brown et al. 2009a, b; Fortanier et al. 2011), global governance and business regulation (e.g., Edelman and Talesh 2011; Scherer and Palazzo 2011), and institutional theory (e.g., Boxenbaum 2006a, b).

We theorize the translation of standards inside the organization by showing the processes and consequences of compliance with the GRI. We show that in this case study, organizational actors interpreted the GRI as: a taken-for-granted standard to use, an important stakeholder in the firm, a performance assessment tool and a provider of legitimacy. Through this interpretation process, organizational actors developed a CSR construct focused on reporting, which influenced their management practices. We argue that the GRI is, therefore, altering the definition of CSR and the way CSR is managed within the organization. We show that in North Co., substantive GRI adoption led to unintended consequences on CSR management practices, specifically it influenced: the management structure and CSR committee function; the choice of CSR activities, the relationships between subsidiaries, the temporal dimension of CSR management, and the interpretation of CSR performance. Through those changes in the CSR management practices, we suggest that the firm maintains its legitimacy by documenting its CSR activities and translating them into a report, rather than by assessing and improving the CSR activities. The emphasis is, therefore, placed on CSR representation rather than CSR performance. Thus, our research demonstrates the key role played by an international sustainability standard—the GRI—in shaping CSR in an MNC.

We make three main contributions. First, we contribute to the standardization literature by providing empirical insight into the internal dynamics of standard compliance. Our research sheds light onto the processes and consequences of standard adoption and reveals the need to take into account the intended versus actual use of standards inside firms. We show how substantive standard adoption can have unintended consequences on management practices as organizational actors construct the meaning of standard compliance. Second, we provide an account of the influence of CSR reporting in shaping organizational practices inside an MNC. As many standards encourage a form of reporting (e.g., Dow Jones Sustainability Index listing requires firms to complete an extensive questionnaire on their CSR practices), we demonstrate the need for research on the impact of reporting on organizational practices and more generally, on the role of reporting in the field of CSR. We highlight the opportunity for synergy between communication theory (in this case, we use the work of McLuhan 1964) and standardization research to discuss the role of reporting. Finally, our findings point to the need to examine the evolution of sustainability standards, as well as the dynamics (or absence of) between standards in order to better understand the influence of the new global governance infrastructure on firms’ CSR practices. This paper, therefore, lays foundations for research into the intra-organizational practices, structures and systems that arise from standard compliance.

The remainder of our paper is structured as follows. First, we provide an overview of the literature on new global governance with an account of the role of international sustainability standards, as well as an institutional perspective on standardization. We then provide an account of our theoretical framing device namely, translation. After a description of our research design, context, data collection and analysis strategies, we present our empirical findings. These are discussed in relation to the extant literature before we draw conclusions and suggest avenues for further research.

The New Global Governance Infrastructure and the Emergence of Standards

The global governance literature has illustrated the recent shift in the balance of power between governments, economic actors and civil society (Crane et al. 2008). Within this changing global landscape has emerged a new set of institutions of global governance, which involve actors such as corporations, international organizations and states (Moon et al. 2011). Scherer and Palazzo (2011) have noted a recent shift from ‘hard’ law (formal rules and sanctions) to ‘soft’ law (voluntary self-regulation). This new ‘soft governance’ infrastructure is characterised by non-legal forms of regulation at an international level (Djelic and Sahlin-Andersson 2006). More generally, Jacobsson and Sahlin-Andersson (2006) have identified three interrelated modes of transnational regulation: rule setting (through codes of conducts, guidelines, etc.), monitoring (from rankings, accreditation, audits, etc.) and agenda setting (in arenas and forums to disseminate ideas and recommendations).

Firms, and particularly MNCs, play a key role in this new global governance matrix (van Oosterhout 2010), as they are both influenced by, and influencing the new global context and rules (Scherer et al. 2006). The new ‘soft’ regulation infrastructure has thus succeeded in creating new expectations for businesses. For example, MNCs are now seen as both a part of the problem and as a solution to major societal concerns (e.g., climate change). MNCs take on different roles and responsibilities in this global environment where there are fewer distinctions between the public and private spheres (Kobrin 2008). This new regime is helping to promote greater accountability in corporations as firms voluntarily engage in self-regulation and transparency exercises. However, there are still many questions regarding the power, legitimacy and effectiveness of this new global governance infrastructure (Banerjee 2010). Furthermore, this ‘soft’ regulation of corporate conduct has often been criticized for being less effective than government regulation, particularly in developed countries (Vogel 2010).

There is a dearth of empirical research into the impact of global governance institutions on firms, as the literature is dominated by theoretical articles on the role of corporations in global governance issues (e.g., Hess 2007; Scherer et al. 2006; van Oosterhout 2010). However, the business regulation literature does offer an empirical perspective on the mechanisms of private ‘hard’ regulation (Edelman 1990; Parker and Nielsen 2011), discussing, inter alia, the ideas of ‘responsive regulation’ (Braithwaite 2011) and ‘regulatory capitalism’ (Levi-Faur and Jordana 2005). Such political science studies explore the new global order of regulation and its impact on practices. Research such as Edelman and Talesh (2011) has shown the interactions between the organizational (business community) and legal (global governance institutions) fields and reinforced the need for more research on the processes involved in compliance with regulation. Whereas previous research has offered empirical examples on the diffusion and translation of ‘hard’ laws in firms (Edelman 1992), our study investigates how firms enact ‘soft’ regulation, in particular, international sustainability standards.

Research on International Sustainability Standards

The field of CSR is a relevant context for studying standardization processes as the number of sustainability standards has multiplied in recent years forming ‘standards markets’, where standard organizations compete (and collaborate) for adoption (Reinecke et al. 2012). These new sustainability standards specifically address questions related to the social and environmental performance of firms (Gilbert et al. 2011). Standards provide a form of self-regulation, as corporations adopt voluntary standards that go beyond governmental regulation (Christmann and Taylor 2006), generally differing from firms’ codes of conduct, as they are developed through multi-stakeholder initiatives (Rasche 2009). In a summary, Slager et al. (2012) identified three characteristics that defined standards’ regulatory power: design (established set of common practices), legitimacy (authority based on multi-stakeholder nature) and monitoring (rule enforcement through monitoring of practices). Behnam and MacLean (2011, p. 48) classify these standards into three categories: principle-based standards (e.g., the UN Global Compact), certification-based standards (e.g., the SA8000) and reporting standards (e.g., the GRI). Slager et al. (2012) have also added financial indices (such as The FTSE4Good or the Dow Jones Sustainability Index) to this list.

Research (mainly large quantitative studies) has provided some empirical evidence on the widespread adoption of standards across corporations (e.g., Arevalo et al. 2013; Delmas and Montes-Sanchos 2011; Delmas and Toffel 2008). For example, Fortanier et al. (2011) have shown a link between adherence to international sustainability standards and the harmonization of CSR reports between corporations. However little is known about the ‘journey’ of such standards within organizations and their actual influence on organizational practices (Heras-Saizarbitoria and Boiral 2013).

Institutional Perspectives on Standardization

Institutional theory has been widely used to understand standard compliance (e.g., Aravind and Christmann 2011; Boiral 2007; Haack et al. 2012) and numerous studies have highlighted decoupling as a response to standard adoption, leading to ‘window dressing’ or ‘greenwashing’ practices (Behnam and MacLean 2011). The concept of decoupling was introduced by Meyer and Rowan (1977) and refers to discrepancies between policy and practice in organizations, leading to firms not fulfilling their commitments. Firms may ceremonially adopt practices but fail to implement activities and therefore decrease internal coordination and control. Fiss and Zajac (2006, p. 1175) defined such decoupling in organizations as “situations where compliance with external expectations may be merely symbolic rather than substantive, leaving the original relations within an organization largely unchanged”.

Simpson et al. (2012) argue that standards often fail to deliver as firms that adopt them do not have the technical capabilities to employ them fully, therefore creating a gap between the standards’ institutional requirements and the firms’ existing capabilities. In exploring the discrepancies between the rhetoric and reality in standard adoption, Christmann and Taylor (2006) have studied the determinants of standard compliance and shown that firms select their level of compliance based on stakeholder expectations and firm capabilities. However, Haack et al. (2012) have shown that decoupling could be a transitional state in the standardization processes.

Translation of Standards Inside the Firm

In order to study the processes involved in standard compliance, our research draws on Scandinavian institutionalism and particularly on the concept of translation (Czarniawska and Joerges 1996), which refers to “the modification that a practice or an idea undergoes when it is implemented in a new organisational context” (Boxenbaum and Strandgaard Pedersen 2009, p. 190). This branch of neo-institutionalism draws on social construction (Berger and Luckmann 1966) to study the dynamics of circulating ideas in different organizational settings (Sahlin and Wedlin 2008). This process type of research focuses on how and why new ideas become accepted and their consequences for day-to-day organizational practices (Sahlin and Wedlin 2008). On a macro level, we know that standards can ‘travel’ across organizations (Czarniawska and Joerges 1996; Frenkel 2005; Zilber 2006). As an example, Boxenbaum (2006a, b) has studied how business actors have translated a ‘foreign’ practice in their local context by developing an institutional hybrid, a construct in between the ‘foreign’ and familiar concepts. Research in this field helps us understand how organizational actors adapt new ideas and practices to their own organizational context. However, we know very little about the micro-level processes of translation of standards, which could, in this case, provide further insight into standard compliance and implementation issues.

CSR Reporting and the Case of the GRI

The GRI, a multi-stakeholder initiative, was established in 1997 as a joint project by the US Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies and the UN Environment Programme (Waddock 2007). Its stated goal is to encourage dialogue between corporations and stakeholders through firms’ disclosure of information on economic, social, governance and environmental performance (GRI 2011a). Firms need to report on: first, their profile (context information on profile, strategy and governance); second, their management approach (how they address relevant topics) and third, a series of performance indicators (comparable information on social, environmental and economic performance; GRI 2011c, p. 5). The GRI provides information on the scope and quality of reporting, not the actual performance of CSR. Thus it has developed reporting norms on what to report and how to report, without any binding requirements. It is a voluntary standard, and as Willis (2003, p. 235) stated “the Guidelines do not represent a code of conduct or a performance standard”. By providing reporting guidelines, the GRI aims at promoting organizational transparency and accountability as well as stakeholder engagement. The GRI also provides application-level information, as corporations can self-assess their reports (or get a third party assurance), based on the number of GRI indicators disclosed in their reports. Depending on their disclosure level, corporations are awarded a level A, B or C (GRI 2011b). This ‘grade’ can be included in a firm’s CSR report.Footnote 2

The recent proliferation of international sustainability standards has caused a certain degree of confusion, but the GRI is emerging as a dominant player in this field (Waddock 2008). Effectively, there is now no competition for the GRI, as it is the most widely used reporting standard (Etzion and Ferraro 2010), with 85 % of the world’s 250 largest corporations following its guidelines (KPMG 2011, p. 20). Consequently, the GRI has received a lot of attention in academic publications (e.g., Adams, 2004; Brown et al. 2009a, b; Levy et al. 2010; Nikolaeva and Bicho 2011; Waddock 2007). However, its influence inside firms has been largely ignored (Fortanier et al. 2011).

One of the major contributions of the GRI is its multi-stakeholder approach (Brown et al. 2009a, b; Waddock 2007), which includes a broad coalition of actors from the business, NGO, academic and governmental sectors. The GRI has institutionalized this multi-stakeholder discussion on reporting and, more broadly, on accountability. However, there is an uneven representation of companies in the GRI (Drori et al. 2006), as it is most followed by MNCs from developed Western countries. In addition, MNCs, major accountancy firms and large consultancies are the most influential actors in the GRI (MacLean and Rebernak 2007), with only a small contingent of NGOs, labour organizations, and small and medium enterprises (Brown et al. 2009a). Western MNCs are therefore helping set the agenda on reporting based on their own interests. According to Adams and McNicholas (2007, p. 484), the guidelines’ lack of universal applicability creates a “perceived unfairness inherent in imposing Western standards of social behaviour (and associated reporting practices)”. Another criticism of the GRI is related to the difficulties of internalizing its principles, as “[the GRI] promotes the construction of a set of indicators instead of instilling business with values to change their mentality so they can subscribe to the assumptions of [sustainable development]” (Moneva et al. 2006, p. 135).

Brown et al. (2009b) also noted that in standardizing reporting practices, the GRI is standardizing CSR as a business practice. Etzion and Ferraro (2010, p. 1102) found that although the GRI was intended to be a reporting guideline, “over time, GRI has placed greater emphasis on reporting principles and less on providing specific templates and metrics to be used in reports”. It is clear that the GRI is now providing more information about what to report (performance indicators), than how to report (protocol of reporting); placing importance on certain issues, such as materiality, stakeholder and social inclusiveness (Brown et al. 2009a; Etzion and Ferraro 2010). As a result, companies are integrating these issues into their business practices.

From an institutional perspective, DiMaggio and Powell (1983) and Meyer and Rowan (1977) suggest that organizations need legitimacy in order to survive. The GRI, by providing standardized CSR reporting guidelines, helps corporations achieve legitimacy. Research has already shown that firms adopt the GRI guidelines as a response to stakeholder pressures (Perez-Batres et al. 2012). According to Brown et al. (2009a), the reasons for joining the GRI are principally reputation management and brand protection. Thus companies joining the GRI aim at gaining credibility, without necessarily achieving certain levels of CSR performance (Fortanier et al. 2011). According to Levy and Kaplan (2007, p. 438), the GRI can therefore provide legitimacy at a low cost, as the standard requires firms to document managerial processes rather than assess their outcomes; and therefore “compliance can thus provide a degree of legitimacy without necessarily imposing substantial costs”. Over the years, the GRI has become a very successful institution, as “social reporting, and the associated language, concepts and assumptions, have rapidly become a taken for granted practice amongst large MNCs, and GRI has played a dominant role” (Brown et al. 2009a, p. 578). The GRI, therefore, reinforces the importance of CSR reporting as a business practice and provides corporations with the legitimacy needed to justify their CSR practices. Furthermore, the GRI has successfully institutionalized the reporting discourse, which has led to new norms and practices of corporate responsibility and accountability.

Given the extensive research on CSR reporting and the influence of the GRI, there has been surprisingly little research on the extent to which CSR reporting practices influence organizational practices within corporations, with only a few studies dealing with such issues (e.g., Adams and McNicholas 2007; Zambon and Del Bello 2005). Adams and Frost (2008) examined how CSR key performance indicators (KPIs) are used in decision-making and management practices in corporations. Adams and McNicholas (2007) investigated the integration of CSR reporting in some management practices, such as planning or decision-making. Gond and Herrbach (2006) offered a theoretical article on CSR reporting as an organizational learning tool. Studies on the influence of CSR reporting in corporations often demonstrate its particular effects on stakeholder management practices. It has been shown that reporting activities can become a way for corporations to interact with stakeholders and subsequently adjust their CSR activities (Zambon and Del Bello 2005). Brown et al. (2009a, b) have shown that CSR reporting has become a standardized practice through the institutionalization of the GRI, arguing therefore that the GRI has had an impact on the emergence of new firms’ behaviour. However, this study analysed the institutionalization of the GRI, rather than the standardization of CSR reporting practice inside firms.

Research Design

A considerable literature has emerged on the adoption of international sustainability standards across firms at the macro-level (e.g., Arevalo et al. 2013). It is, therefore, interesting to open the ‘black box’ and investigate the translation of a standard inside corporations. As the voluntary nature of the emergent standards leaves corporations with freedom to interpret and engage in certain practices (Behnam and MacLean 2011; Clapp 2005), it is useful to examine exactly how sustainability standards are operationalized within the organization (Heras-Saizarbitoria and Boiral 2013) and their influence on organizational routines and practices. Although the GRI has already been widely studied (e.g., Brown et al. 2009a; Toppinen and Korhonen-Kurki 2013), further research is needed on the ‘receiving end’ of its guidelines, to compare the stated intention of the use of the GRI with its actual use inside a firm. In order to do this, our exploratory study seeks answers to the research question: “how does a macro-level institution such as the GRI, influence micro-level CSR organizational practices?” Hence, we carried out an 18-month qualitative inductive case study seeking an in-depth understanding of internal organizational processes (Yin 2009). As the paper is based on a single case study, the specific processes and consequences of the GRI inside North Co., need to be regarded as preliminary and exploratory findings. They do, however, provide a first attempt at studying the intra-organizational dynamics of how sustainability standards are translated within a firm.

Research Context

North Co., is a global market leader in the business-to-business manufacturing sector with offices in around 30 countries and approximately 80,000 employees. CSR is managed through a CSR committee led by one of the firm’s senior vice presidents (from the corporate head office located in North America) and the committee includes other head office members as well as members from the two divisional headquarters (located in North America and Europe). These members are drawn from different divisions: communication, legal services, human resources, health and safety and government affairs, though most are from the communication and public affairs services. This committee elaborates the firm’s CSR strategy, divided into six key pillars (employees, responsible products, citizenship, governance, operations, suppliers) in a consultative mode. This CSR strategy is then globally integrated into the corporation. North Co.’s first CSR report was published in 2007 and since 2009 the reports have followed the GRI guidelines. In 2011, the report was verified by the GRI for the first time, and was awarded level B accreditation. The firm is, therefore, a relatively late mover into the sustainability reporting scene.

Data Collection

Our case study relies on four sources of information, collected between October 2011 and January 2013: (1) semi-structured interviews, mainly with members of the firm’s CSR committee, (2) digitally recorded longitudinal observation of internal CSR committee meetings, (3) documentation from the MNC (e.g., CSR reports and website) and (4) documentation from the GRI (e.g., G3 CSR reporting guidelines). We were granted access to interview employees and observe CSR committee meetings in three different offices (the corporate headquarters and two subsidiaries), located in North America and Europe. Table 1 describes the different sources of data collected for this study.

We conducted a total of 24 semi-structured interviews with employees involved in CSR management in different divisions, such as operations, supply chain, human resource management, legal counsel and communication. The areas of inquiry covered in the interviews included, amongst other things, the interviewee’s organizational role, their interpretation of CSR, the management of CSR, both in their division and throughout the MNC, the relations between the different divisions and the head office, as well as the CSR reporting process. We were also given access to the CSR committee weekly conference calls, where members of the divisions meet to discuss CSR management. We digitally recorded 27 weekly conference calls and 7 workshops (a total of approximately 26 h of non-participant observation). The observations, of both conference calls and meetings, provided ‘naturally occurring data’ (Silverman 2002, p. 159). The recorded observations quickly became the primary source of information because it proved to be a very rich and representative source of information on the corporation’s CSR management practices. The weekly conference calls provided an ongoing account of the negotiations around the implementation of the GRI, whereas the interviews offered a retrospective account of the standardization processes. All interview and meeting recordings were transcribed verbatim. The analysis of these primary sources of data was combined with the examination of all of the corporation’s CSR reports (from 2007 to 2011) in order to better understand the influence of the GRI over time. In addition, we examined documents from the GRI (G3 Sustainability Reporting Guidelines and GRI website). The primary data were compared with the GRI guidelines in order to better highlight and understand discrepancies between the stated intentions and the actual use of the guidelines at North Co.

Data Analysis

In our data analysis, we followed what has been named by Langley and Abdallah (2011), the ‘Gioia template’ of qualitative studies (see Gioia et al. 2013). Dennis Gioia’s work has been characterized by interpretive, single case study research that relies on narratives to produce process accounts of organizational phenomena and which introduces novel concepts to the literature (e.g., Corley and Gioia’s 2004 study of organizational identity changes and development of new aspects of identity ambiguity). Following Corley and Gioia’s (2004) interpretive process-based template, we conducted a three-stage data analysis process (see Table 2. Data Structure). First, we identified narratives associated with the CSR reporting and the GRI in the firm (named first order concepts). Second, we grouped those narratives into categories (second order themes), and finally we constructed two main findings (aggregate dimensions). This narrative approach helped us understand how the organizational actors perceived, made sense of, and used the GRI guidelines. This helped us deal with the complex and contextually embedded processes of standard adoption (Langley 1999). Following Rhodes and Brown (2005), and Humphreys and Brown (2008, p. 405) defined narratives as “specific, coherent, creative re-descriptions of the world, which are authored by participants who draw on the (generally broad, multiple and heterogeneous) discursive resources locally available to them”. The emergent narratives were used to identify and categorise the events, activities and choices that form the standardization processes.

Findings

This section identifies the key narratives associated with the GRI (and more generally with reporting) inside the MNC. These inform two main findings sub-sections. First, we examine the processes involved in the standardization of CSR inside the organization. The findings indicate that CSR reporting has become the main task of the CSR committee, and that the GRI stands out as the ultimate guideline on how to report. The study therefore suggests that the CSR committee developed a CSR construct focused on reporting and transparency. Second, we explore the unintended consequences of this new CSR construct on management practices. Table 2 details both the processes and consequences of standardization.

Processes of Standardization: Development of a CSR Construct Based on Transparency

In this section we illustrate the interpretive activities that shape the way CSR is perceived by the organizational actors at North Co. Table 3 provides illustrations of the different processes of standardization inside the firm. Overall, the findings demonstrate that the GRI is becoming institutionalized within the firm, as it becomes a taken-for-granted norm with which to comply and is therefore perceived as: an important stakeholder, a performance assessment tool and a provider of legitimacy.

A first indication of the effects of this process is provided by the chronology of CSR reporting by the MNC. North Co.’s first CSR report was published in 2007, and did not include a reference to the GRI guidelines. The following report in 2008 was much more robust in terms of data, but also did not follow the GRI guidelines. The 2009 report included a GRI ‘guideline table’ listing the different GRI indicators and the corresponding report sections. In 2010, the report contained a ‘GRI disclosure table’, which included the firm’s degree of compliance with each GRI indicator. The report also included a self-declared assessment of the report’s application level of disclosure (level B). In 2011, the report was verified by the GRI, who declared it to be level B. This shows that over the years, the GRI is taking a more prominent place in the corporation’s CSR report.

As mentioned in the literature review, the GRI is becoming a powerful player in the field of CSR generally (Brown et al. 2009a, b; Etzion and Ferraro 2010). In our case this was confirmed by initial interview data as members of the North Co.’s CSR committee were very clear about the necessity of following GRI guidelines:

we have an external obligation to produce the report […] we have an obligation to make this report GRI compliant (Head office employee)

Our findings show that the GRI is a key element in this process of improving reporting activities. Members of the committee often discuss the importance of following GRI guidelines, but never debate whether or not they should use the guidelines, as discussions are always centred on ‘how’ to use them. At times, committee members seem almost dependent on the GRI guidelines. The GRI guidelines are, therefore, becoming a taken-for-granted aspect of CSR reporting in the corporation, as the process of producing a CSR report is seen as a necessity, and the use of the guidelines is perceived as mandatory. The GRI is also perceived as an important stakeholder. Members of the CSR committee felt that one of the first needs of the report was to fulfil GRI requirements. Moreover, some employees felt that the report was addressed to the GRI and was excluding other stakeholders such as employees and customers.

The evidence from the case study also suggests that the GRI’s application level information (corporations get a level A, B or C of disclosure), is being used in the firm as a performance assessment tool that is shaping the design of CSR inside the firm. The importance of meeting GRI requirements is present in the firm’s CSR committee discussions. As one employee noted when discussing the production of the 2011 CSR report:

we have to work on GRI and develop new indicators following our objective to become more robust on a level B and finally be mature enough for the next level (Subsidiary B employee)

The goal of receiving a higher “grade” is therefore becoming the end result, influencing the processes necessary to achieve it. The GRI, which was intended as a reporting standard, is thus becoming a performance standard. It is clear that although the initial goal of the GRI was to provide information on CSR reporting, with the introduction of the level system, it is also producing a performance assessment tool. This emphasizes the corporation’s aim to improve their reporting practices, not their actual CSR performance. As an employee said:

we report a lot on effort but not on our performance (Head office manager)

The aim of the CSR committee is to increase their level of disclosure rather than the actual CSR performance. The GRI therefore influences the meaning of ‘performance’ in the firm, which shifts the focus from increasing CSR performance to increasing CSR disclosure. The GRI is also perceived as a provider of legitimacy. It provides validity to the report, granting it its ‘seal of approval’, as employees explained it. Organizational actors are also seeing the GRI as more legitimate than other reporting standards. In addition, it provides legitimacy to the CSR activities by offering a clear list of CSR indicators and therefore defining what can and cannot be included in the report. The GRI, therefore, provides validity to CSR activities as well as an accepted definition of the nature of CSR.

Unintended Consequences of Standardization: Reporting’s Influence on the CSR Management Practices

Overall, the organizational actors responded in a strategic way to the pressures of the GRI. They perceived pressures to engage in a transparency exercise through the report, and tried to make the report enhance their business strategy. They developed a CSR construct centred on reporting and representation and this is influencing the way they manage CSR. This section demonstrates that reporting (through the GRI guidelines) is having an impact on: the function of the CSR committee, the notion of CSR performance, the selection of CSR activities, the relationship between the divisions, the CSR management structure as well as the temporal dimension of CSR. Table 4 provides illustrative quotes for each unintended consequence of standardization.

One of the consequences of the standardization is a change in the nature of CSR in the firm. Many employees are unsure of the goals of the CSR committee and whether efforts should to be put on collecting information for the report or managing CSR projects. There is a feeling that CSR is retrospective rather than proactive because so much effort is placed on collecting data for the report. In our analysis, it became clear that CSR management in the firm is centred on the reporting activities. The CSR committee is mostly attended by communication and public affairs employees, reflecting this emphasis on reporting. The CSR committee holds weekly conference calls in order to discuss CSR management across the corporations, and those calls always revolve around the production of the CSR report and website. In the 27 observed conference calls, the discussions were centred on reporting processes (i.e., timeline to submit data, KPIs to be included in report, presentation of GRI tables, photographs to use in the report, etc.) rather than CSR activities. This new status of reporting also influences the meaning of the term ‘CSR performance’. Discussions in the CSR committee conference calls are centred on the improvement of reporting activities, not the actual CSR performance itself. The representation of CSR therefore takes centre stage.

Another consequence on the management of CSR is the choice of CSR activities being influenced by the reporting process. As an example, there were discussions in a weekly conference call about reporting on issues not included in the GRI guidelines. Employees discussed the issue of reporting on a government relations project, for which it was unclear under what GRI KPI it would fall. Here are quotes from this discussion:

Regarding the GRI’s KPI, it is important that we do not ignore the governmental agencies we are working with. The way the report is structured right now, how do we identify that we are on the [governmental agency] advisory board? (Subsidiary A employee)

The GRI wants us to report on industry relation, but where is the place for government relations. Is there some KPI on government relations? (Subsidiary A manager)

It is material for our business, so we should be looking at it. The questions is: do we have the time and capacity to do it? (Subsidiary A manager)

The CSR committee members debated how to report on an issue that is not a GRI indicator, how to track the information on it, or even, if they should report on it at all. In this corporation, the GRI guidelines have clearly become the ultimate guide on reporting, to a point where employees do not even question their usefulness. This provides a specific example of the influence of reporting on the choice of CSR activities, but CSR committee members often mentioned in interview the dichotomy between the reporting and operationalization of CSR inside the firm.

At North Co., CSR is managed by a committee made up of employees from the headquarters and two subsidiaries located in North America and Europe. In order to fulfil the GRI requirements and improve the reporting process, the subsidiaries need to communicate information and exchange ideas. Often during conference calls, CSR committee members from both subsidiaries exchanged information and advice related to the report. As an example, the North American office provided the European subsidiary with their official photo disclaimer (to use when including a photo of employees in the CSR report), hence the European subsidiary did not need to write a new one. The production of the CSR report, in this way, is perceived as bringing the different offices together by increasing communication and therefore enhancing transfer of practice. Indeed, it seems that this collaborative approach is unique within North Co., as a head office employee states:

What I find really interesting with the CSR committee is that we can see the duality of the approaches [of the different subsidiaries], but unlike in other sectors, people in the committee really share their ideas and input. They are very open to ideas from the other group, to see how the other group works. It’s really impressive (Head office employee)

CSR reporting is one of the corporation’s activities that are globally managed, as the goal of improving CSR reporting and consequently their GRI level is helping bring the subsidiaries together. In order to fulfil the reporting goals, the head office has become a coordinator of data collection and this entails a top-down global approach to CSR management.

The final consequence of the standardization of CSR is a change in timeframe of CSR management. This is scheduled around the annual reporting cycle (the firm publishes a CSR report every year in the Spring, generally at the same time as the annual financial report). Some projects, such as the stakeholder consultation, were shortened because they needed to be done within this timeframe. Additionally, this cycle hinders the firm’s capacity for creating a long-term strategy, as the CSR committee is always responding to the short term reporting demands. The employees acknowledge this as a downside of both reporting and fulfilling the GRI requirements. The reporting pressures not only limit the long-term planning of CSR, but also enhance the emphasis on the annual reporting cycle. We call this a change in the temporal dimension of CSR management.

Discussion

There are many different ways corporations can adopt standards, ranging from absolute compliance to a decoupled instrumental adoption of the guidelines. The literature on the GRI and more generally on CSR reporting is divided into two main schools of thought. On one side, authors such as Behnam and MacLean (2011) argue that corporations tend to adopt sustainability standards such as the GRI for strategic reasons and often fail to enact their commitments. At the other end of the spectrum, authors such as Adams and Frost (2008), Zambon and Del Bello (2005) and Gond and Herrbach (2006) view the process of CSR reporting as an organizational learning activity where corporations adopt new management practices based on the information acquired through the reporting process. However, our study shows that standard compliance is a more complex process than this binary portrayal. While North Co.’s CSR committee complied with the GRI principles, it also developed a CSR construct where responsibility equals transparency, which was not the intention of the GRI. This new construct influenced the firm’s CSR management practices, as the importance was on documenting CSR activities, rather than assessing their outcome and improving the activities (Levy and Kaplan 2007). Thus, viewing CSR as a transparency exercise had many unintended consequences inside the firm. The next sections discuss the processes and consequences of GRI compliance in order to better understand the role of international sustainability standards on intra-organizational practices.

Processes of Standardization: Internal Translation of the GRI Inside the Firm

Organizational actors interpret and translate practices to adjust them to their organizational context (Czarniawska and Joerges 1996). The concept of translation helps us understand the complex processes of standard compliance in a way that goes beyond the traditional binary view of standard adoption (i.e., adoption vs. non-adoption). Following Boxenbaum’s (2006a, b) research on the development of new CSR constructs by business actors, we analysed the influence of the GRI (as an institution) inside an MNC and its impact on the construction of the notion of CSR. In the findings section, we have identified the processes involved in the standardization of the GRI inside the firm, which led to the development of a CSR construct centred on reporting. We have shown how the organizational actors framed the GRI as an important stakeholder, a performance assessment tool and a provider of legitimacy. Thus, the GRI, intended as a reporting guideline, was translated in the firm as a management guideline. In the next section, in order to help us understand how and why reporting is influencing the management practices, we draw on communication theory and particularly the work of McLuhan (1964).

‘The medium is the message’: The Role of the CSR Report

In his 1964 book Understanding Media, McLuhan (1964, p. 7) famously wrote that “the medium is the message”. According to McLuhan, the medium should be the object of study, not the message it carries. In this case, the CSR performance (the message) enables us to notice the crucial role of the CSR report (the medium). The message cannot be separated from the medium, as the medium influences the way the message is perceived. As McLuhan (1964, p. 9) suggests, “it is the medium that shapes and controls the scale and form of human association and action. […] Indeed, it is only too typical that the ‘content’ of any medium blinds us to the character of the medium”. Following this logic, the CSR report is altering what CSR performance is for corporations, as the report becomes a translator of the CSR activities. In the same way that words can convey experiences, CSR reports can make CSR performance explicit. A corporation’s CSR report brings together countless activities happening every day in plants and offices across the world and translates them into a 50-page document. At North Co., it seems that this process has taken centre stage and the focus has shifted from improving CSR performance, to improving CSR representation. Hence in the MNC’s management practices the representation of CSR becomes central and obscures the actual CSR performance.

Outcomes of Standardization: Duality Between Intended and Actual Use of the Standard

The consequence of this overemphasis on representation is that the GRI is framed by the organizational actors as a management standard, rather than a reporting standard. According to the GRI, their guidelines provide a framework to measure and communicate CSR information, but it seems that by institutionalizing reporting language and norms (Brown et al. 2009b), the GRI also standardized certain forms of CSR management practice. Our research shows that there is a duality between the stated aims of the GRI and its actual use in corporations. Table 5 shows the many discrepancies between the intended and actual use of the standard guidelines inside the firm. The GRI’s general mission is to encourage responsible business practices through the disclosure of firms’ economic, social, environmental and governance performance. Our findings suggest that organizational actors actually use the reporting principles as management guidelines, by amongst other things, viewing the GRI as a CSR performance assessment tool.

Following Fiss and Zajac’s (2006) view on decoupling as a nuanced process rather than a binary choice (adoption vs. non-adoption), we highlight what happens in the grey zone of standard adoption, when firms adopt certain practices and language—but not completely. The research shows that North Co., does implement the reporting standard requirements, but not in the way it was intended by the GRI. This form of adoption, although considered as substantive in the typical decoupling literature (the firm does enact its commitment to report on CSR), leads to unintended consequences. In this case, the firm is complying with the standard requirements in terms of reporting, however, they are also using the guidelines as a management standard, which had many consequences on the nature of CSR inside the firm, such as changes to the management structure and CSR committee function; the choice of CSR activities, the relationships between subsidiaries, the temporal dimension of CSR management, and the interpretation of CSR performance. Research on decoupling in standard adoption points to many factors influencing the level of implementation, such as stakeholder expectations and firm capabilities (Christmann and Taylor 2006; Simpson et al. 2012). However, our findings emphasize the need for more nuanced accounts of standard compliance, which take into account the unintended consequences of substantive standard adoption.

Legitimacy from Reporting?

Corporate communication and reporting have clearly become important processes in the quest for enhanced legitimacy (Coupland 2005), as corporations feel the need to disclose information on their CSR engagement to forestall legitimacy concerns (Arvidsson 2010). Indeed, Palazzo and Scherer (2006) have described a shift towards more communication engagement between firms and society (Palazzo and Scherer 2006). At North Co., the CSR committee developed a CSR strategy focused on the disclosure of information. By doing so, they responded to social expectations while ‘evading’ implementation challenges, as they concentrated their efforts on CSR representation, rather than on actual CSR performance. Research has already shown that the GRI guidelines are often used to enhance external credibility and reputation at a relatively low cost (Levy and Kaplan 2007). It appears that corporations use the guidelines to increase their legitimacy, both internally and externally (Hedberg and von Malmborg 2003), as increasing the reporting standard is less expensive than increasing the actual CSR performance. Our research surfaces other benefits of using the GRI guidelines, particularly in terms of internal legitimacy. For example, in our case study the GRI offered not only a validation of their CSR practices, but also a source of justification for the new reporting construct, a response to transparency pressures, as well as structured guidelines and a defined schedule. All organizational actors inside the firm readily accepted the GRI, as it provided legitimate and useful guidelines for action. As a powerful CSR institution, it therefore legitimized a management approach centred on reporting thereby granting the firm its seal of approval, and supporting the overemphasis on transparency over performance.

This tendency towards the representation of CSR over the actual performance is aligned with Bondy et al.’s (2012) research, which showed that MNCs increasingly engage in a strategic and profit-led form of CSR, over a broader societal understanding of CSR. MNCs are an important stakeholder in the GRI, as they are, along with major accountancy firms and large consultancies, the most influential actors in the GRI structure (MacLean and Rebernak 2007). In helping construct GRI guidelines, MNCs are also setting an agenda on reporting based on their own interests. As Fortanier et al. (2011, p. 670) argue, “the reason why MNEs have been instrumental in developing and adhering to global CSR standards is because it creates new institutional arrangements that better fit their corporate context”. It is clear that companies profit from having GRI-approved CSR practices centred on reporting. This enables the corporation to maintain its legitimacy and license to operate by documenting its CSR activities and translating them into a report. Thus in illustrating how the GRI provided legitimacy to engage in CSR as a transparency exercise, we raise questions related to the role of reporting and CSR communication more generally, particularly in terms of corporate accountability.

Reconceptualising the Influence of Standards Inside Firms

Scherer and Palazzo (2011) have argued that governance levels have shifted from a national to a global level (by replacing national ‘hard’ law with international ‘soft’ law). Our research indicates the key role played by a global governance institution—the GRI—in shaping CSR in a MNC, as organizational actors develop their own interpretation of ‘soft’ regulation compliance.

Institutional perspectives on the diffusion of regulation in firms (Edelman 1990, 1992) have analysed the translation of ‘hard’ laws in firms. Edelman and Talesh (2011) have shown that firms construct the meaning of compliance to legal requirements and that this construction can become institutionalized and diffused across organizations, which in turn, can influence the law itself. Where Edelman and Talesh (2011) have conceptualized compliance to ‘hard’ law as a process on a macro-level, we have tried to establish the micro-level organizational processes of compliance to ‘soft’ regulation through standards. As firms adopt more and more sustainability standards, it is important to understand how they construct the meaning of compliance, especially as the standards’ potential to enhance corporate accountability has been questioned (Behnam and MacLean 2011).

Our findings suggest that the GRI, while explicitly promoting reporting standardization, is implicitly enabling a standardized approach to CSR management centred on reporting. As the firm developed its new CSR construct, the emphasis shifts to documenting CSR activities and translating them into a report, rather than assessing or improving their effectiveness. Although this was not the intention of the GRI, current guidelines allow firms to construct the meaning of compliance and strategically respond to the standard’s requirements. As ‘soft’ governance standards are particularly flexible (no binding requirements, self-assessment of compliance, etc.), it is relatively easy for firms to develop their own interpretation of compliance. We therefore raise questions regarding the construction of compliance with ‘soft’ regulation. Simpson et al. (2012) argued that the fit/misfit between the standards’ requirements and the firms’ existing capabilities could explain the adoption and effectiveness of standards. We add that before the standard integration stage, the interpretation of the standard requirements inside the firm influences the way it will be implemented. Firms act in a strategic way by constructing their own version of compliance.

Our work also raises questions regarding the role of reporting in sustainability standards. As many standards imply a form of reporting (for example, to be listed on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, firms need to fill an extensive questionnaire on their CSR practices), we question the impact of reporting on the management of CSR inside firms. Previous research has suggested an unambiguous relationship between global institutions such as the GRI and a standardization of CSR practices across national systems (Fortanier et al. 2011). The homogenization of institutional environments across national business systems has been shown by Matten and Moon (2008), who explained that self-regulatory institutions such as the GRI have acted as a coercive isomorphic draw towards a standardized ‘explicit’ form of CSR. Fortanier et al. (2011) also found that in complex and dynamic institutional environments, the adoption of global standards can help MNCs deal with the numerous, and sometimes conflicting, demands and yet maintain their legitimacy. We add to this thesis by arguing that the GRI is also implicitly promoting a standardization of CSR management inside corporations centred on reporting.

The Dynamics of Standardization

Our findings on the overwhelming influence of the GRI inside a firm highlight the need to examine the relationships (or lack of) between sustainability standards to better understand the influence of the new global governance infrastructure on firms’ CSR practices. As mentioned previously, the GRI has become a successful institution (Brown et al. 2009a; Etzion and Ferraro 2010), helping standardize CSR reporting as a business practice. This was clearly visible at North Co., where the GRI principles were becoming the taken-for-granted norms. The GRI has established itself as the dominant guideline in terms of CSR reporting. However, corporations also use the standard to guide their CSR management practices. As Brown et al. (2009b, p. 190) argue, the:

GRI did not aspire to define, certify or audit performance. Rather, its role would be to create a language which could be used by others to form judgements about the reported performance, and which could over time lead to the emergence of a societal consensus about what constitutes acceptable norms of behaviour with regard to sustainability.

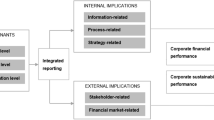

The GRI was intended as a reporting standard, to be used alongside other CSR standards, such as codes of conduct (UN Global Compact) or management standards (ISO 14001, ISO 26000) for example (see Fig. 1). However, at North Co., the GRI has assumed an overwhelming importance, influencing the CSR policy, management and reporting. Although the firm also uses other standards (such as the UN Global Compact), they do not have the same impact on CSR management practices.

Our research, therefore, highlights the importance of studying the dynamic relationships between standards. In this case, the firm concentrated their efforts on the adoption and implementation of one particular sustainability standard, the GRI. Our findings show that complying with one standard does not necessarily lead to greater corporate responsibility, as sustainability standards are intended to be used in collaboration with others (codes for CSR policy, management standards, certification of products, reporting standards, etc.), as each standard fulfil a specific role.

This enhances the need for standard organizations to better understand how their standard interacts with others, which could lead to better coordination between the various sustainability standards. In the specific field of reporting, this would mean greater harmonization between the GRI and other reporting organizations such as the International Integrated Reporting Committee, the Carbon Disclosure Project and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. More generally, we also need to take into account the relationships between reporting and management standards such as the ISO 26000.

To better understand the dynamics of standardization, it would also be interesting to understand the impact of the new GRI G4 guidelines on firms. As our findings pointed to the problems involved in the GRI’s (2013) application level, our study reinforces the need for the new G4 guidelines, launched in May 2013. With the departure of the application levels (A, B or C), the new G4 guidelines may strongly change the GRI’s influence on firms. In this light, it will be interesting to see if the G4 also addresses the other issues raised in the paper. For example, by removing the application level, firms will not be able to assess their disclosure performance in relation to other firms as easily (in a similar way to index and rankings where a hierarchy between firms is established). Future research can consider how this will impact the translation of the GRI inside firms. Our paper therefore emphasizes the need to better understand the interactions between emerging standards and their intra-organizational application. The field of sustainability standardization is therefore evolving, creating new opportunities to study the changing standards, but also the dynamics between standards.

Conclusion and Implications for Future Research

In recent years, CSR reporting has become a virtually mandatory practice in MNCs, and the GRI has evolved alongside this into a very powerful institution (Brown et al. 2009a, b; Etzion and Ferraro 2010). This has resulted in important changes in terms of CSR management inside MNCs, an area still under-researched (Fortanier et al. 2011). We have attempted to fill this gap by providing an exploratory empirical account of the influence of international sustainability standards, particularly the GRI, on an MNC’s organizational practices.

To summarize, the GRI is having a significant impact on an MNC’s practices, influencing both its CSR reporting and its management efforts (see Fig. 2). At an intra-organizational level, the outcome of this is an overemphasis on CSR representation over CSR performance which, in turn, is leading to unintended consequences on CSR management practices. Thus, our study sheds light on the influence of the global governance structure on intra-organizational CSR management, by conceptualizing and illustrating the actual influence of the GRI on a firm’s CSR practices.

Our research contributes to the field of standardization by enhancing the understanding of processes and consequences involved in the translation of standards within an organization. We have moved away from the traditional binary view on standard compliance where firms either adopt standards (reporting as an organizational learning tool) or do not (decoupling of policy and practice) to provide a more nuanced account of the unintended consequences of substance standard adoption. We also contribute to the global governance literature by highlighting the dynamic relationship between standards in order to understand how they contribute to corporate accountability. Finally, we have revealed the significance of reporting and its influence in shaping organizational practices inside an MNC and the construction CSR as a transparency exercise. An implication of these findings for practice is to highlight the need for greater coordination between the various sustainability standards in order to increase their potential to improve corporate accountability.

This paper, therefore, lays foundations for future research on the intra-organizational practices, structures and systems that are the result of standard compliance. A number of limitations need to be considered. First, the research is based on a single case study, therefore the findings might not be transferable to all other firms engaged in CSR activities. We have offered an exploratory account of standard compliance, which could now be enhanced by larger scale analysis of the actual influence of standards inside firms. Further research could expand sample size and refine the processes and consequences of standard translation in firms. With a larger data sample, research could, for example, compare early and late standard adopters.

Further research might also explore the impact of standards on management of CSR in MNCs at a subsidiary level. It would be interesting to study the differences in the influence of standards at the global and local level. The data collected for this study are formed from observations of CSR committee meetings and conference calls, as well as from interviews with employees engaged in the CSR committee. It would be interesting to investigate the management of CSR at a more local level (i.e., directly in the subsidiaries) and analyse the influence of CSR reporting and the GRI guidelines in those contexts. In addition, this paper offers an exploratory account of the influence of the GRI inside a firm, but it would be interesting to study the dynamics between the different sustainability standards and their combined (and isolated) impacts on intra-organizational practices. Furthermore, in the light of the recent changes of the GRI (2013) guidelines with the introduction of the G4 guidelines in May 2013, it would be interesting to study the evolution of the standard’s impact on firms. Future research could also include a critical investigation into the over-emphasis on transparency and what this means for CSR. It would also be interesting to study the implications of a CSR approach centred on transparency in order to answer questions such as: does reporting lead to greater firm accountability?

Notes

North Co. is a pseudonym.

This is the case in the GRI G3.1 guidelines, followed at the time of the research. The new G4 guidelines, launched in 2013 and not yet implemented in firms, have dropped the application level information.

References

Adams, C. A. (2004). The ethical, social and environmental reporting-performance portrayal gap. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 17(5), 731–757.

Adams, C. A., & Frost, G. R. (2008). Integrating sustainability reporting into management practices. Accounting Forum, 32(4), 288–302.

Adams, C., & McNicholas, P. (2007). Making a difference: Sustainability reporting, accountability and organisational change. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 20(3), 382–402.

Aravind, D., & Christmann, P. (2011). Decoupling of standard implementation from certification: Does quality of ISO 14001 implementation affect facilities’ environmental performance? Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(1), 73–102.

Arevalo, J. A., Aravind, D., Ayuso, S., & Roca, M. (2013). The Global Compact: An analysis of the motivations of adoption in the Spanish context. Business Ethics: A European Review, 22(1), 1–15.

Arvidsson, S. (2010). Communication of corporate social responsibility: A study of the views of management teams in large companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(3), 339–354.

Banerjee, B. S. (2010). Governing the global corporation: A critical perspective. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(2), 265–274.

Bartley, T. (2007). Institutional emergence in an era of globalization: The rise of transnational private regulation of labor and environmental conditions. American Journal of Sociology, 113(2), 297–351.

Behnam, M., & MacLean, T. L. (2011). Where is the accountability in international accountability standards?: A decoupling perspective. Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(1), 45–72.

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. New York: Anchor.

Boiral, O. (2007). Corporate greening through ISO 14001: A rational myth? Organization Science, 18(1), 127–146.

Boiral, O. (2012). ISO certificates as organizational degrees? Beyond the rational myths of the certification process. Organization Studies, 33(5–6), 633–654.

Bondy, K., Moon, J., & Matten, D. (2012). An institution of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in multi-national corporations (MNCs): Form and implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(2), 281–299.

Boxenbaum, E. (2006a). Corporate social responsibility as institutional hybrids. Journal of Business Strategies, 23(1), 45–63.

Boxenbaum, E. (2006b). Lost in translation. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(7), 939–948.

Boxenbaum, E., & Strandgaard Pedersen, J. (2009). Scandinavian institutionalism: A case of institutional work. In T. B. Lawrence, R. Suddaby, & B. Leca (Eds.), Institutional work: Actors and agency in institutional studies of organization (pp. 178–204). Cambridge, MA: University of Cambridge Press.

Braithwaite, J. (2011). The essence of responsive regulation. UBC Law Review, 44(3), 475–520.

Brown, H. S., de Jong, M., & Lessidrenska, T. (2009a). The rise of Global Reporting Initiative as a case of institutional entrepreneurship. Environmental Politics, 18(2), 182–200.

Brown, H. S., de Jong, M., & Levy, D. L. (2009b). Building institutions based on information disclosure: Lessons from GRI’s sustainability reporting. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(6), 571–580.

Brunsson, N., Rasche, A., & Seidl, D. (2012). The dynamics of standardization: Three perspectives on standards in organization studies. Organization Studies, 33(5–6), 613–632.

Christmann, P., & Taylor, G. (2006). Firm self-regulation through international certifiable standards: Determinants of symbolic versus substantive implementation. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 863–878.

Clapp, J. (2005). Global environmental governance for corporate responsibility and accountability. Global Environmental Politics, 5(3), 23–34.

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 173–208.

Coupland, C. (2005). Corporate social responsibility as argument on the web. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(4), 355–366.

Crane, A., Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). Corporations and citizenship. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Czarniawska, B., & Joerges, B. (1996). Travels of ideas. In B. Czarniawska & G. Sevón (Eds.), Translating organizational change (pp. 13–48). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Delmas, M. A., & Montes-Sancho, M. J. (2011). An institutional perspective of the diffusion of international management system standards: The case of the environmental management standard 14001. Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(1), 103–132.

Delmas, M. A., & Toffel, M. W. (2008). Organizational responses to environmental demands: Opening the black box. Strategic Management Journal, 29(10), 1027–1055.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Djelic, M.-L., & Sahlin-Andersson, K. (2006). Introduction: A world of governance: The rise of transnational regulation. In M.-L. Djelic & K. Sahlin-Andersson (Eds.), Transnational governance: Institutional dynamics of regulation (pp. 1–28). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Drori, G. S., Meyer, J. W., & Hwang, H. (2006). Globalization and organization: World society and organizational change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Edelman, L. B. (1990). Legal environments and organizational governance: The expansion of due process in the American workplace. American Journal of Sociology, 95(6), 1401–1440.

Edelman, L. B. (1992). Legal ambiguity and symbolic structures: Organizational mediation of civil rights law. American Journal of Sociology, 97(6), 1531–1576.

Edelman, L. B., & Talesh, S. A. (2011). To comply or not to comply—That isn’t the question: How organizations construct the meaning of compliance. In C. Parker & V. L. Nielsen (Eds.), Explaining compliance: Business responses to regulation (pp. 103–122). Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Etzion, D., & Ferraro, F. (2010). The role of analogy in the institutionalization of sustainability reporting. Organization Science, 21(5), 1092–1107.

Fiss, P. C., & Zajac, E. J. (2006). The symbolic management of strategic change: Sensegiving via framing and decoupling. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1173–1193.

Fortanier, F., Kolk, A., & Pinkse, J. (2011). Harmonization in CSR reporting. Management International Review, 51(5), 665–696.

Frenkel, M. (2005). The politics of translation: How state-level political relations affect the cross-national travel of management ideas. Organization, 12(2), 275–301.

Gilbert, D. U., Rasche, A., & Waddock, S. (2011). Accountability in a global economy: The emergence of international accountability standards. Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(1), 23–44.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31.

Gond, J.-P., & Herrbach, O. (2006). Social reporting as an organisational learning tool? A theoretical framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 65(4), 359–371.

GRI. (2011a). About GRI. https://www.globalreporting.org/information/about-gri/Pages/default.aspx.

GRI. (2011b). Application level information. https://www.globalreporting.org/reporting/reporting-framework-overview/application-level-information/Pages/default.aspx.

GRI. (2011c). Sustainability reporting guidelines G3.1. https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/G3.1-Guidelines-Incl-Technical-Protocol.pdf.

GRI. (2013). Sustainability reporting guidelines—G4. https://www.globalreporting.org/resourcelibrary/GRIG4-Part1-Reporting-Principles-and-Standard-Disclosures.pdf.

Haack, P., Schoeneborn, D., & Wickert, C. (2012). Talking the talk, moral entrapment, creeping commitment? Exploring narrative dynamics in corporate responsibility standardization. Organization Studies, 33(5–6), 815–845.

Hedberg, C.-J., & von Malmborg, F. (2003). The Global Reporting Initiative and corporate sustainability reporting in Swedish companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 10(3), 153–164.

Heras-Saizarbitoria, I., & Boiral, O. (2013). ISO 9001 and ISO 14001: Towards a research agenda on management system standards*. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(1), 47–65.

Hess, D. (2007). Social reporting and new governance regulation: The prospects of achieving corporate accountability through transparency. Business Ethics Quarterly, 17(3), 453–476.

Humphreys, M., & Brown, A. (2008). An analysis of corporate social responsibility at credit line: A narrative approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 80(3), 403–418.

Jacobsson, B., & Sahlin-Andersson, K. (2006). Dynamics of soft regulations. In M.-L. Djelic & K. Sahlin-Andersson (Eds.), Transnational governance: Institutional dynamics of regulation (pp. 247–265). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Kobrin, S. J. (2008). Globalization, transnational corporations and the future of global governance. In A. G. Scherer & G. Palazzo (Eds.), Handbook of research on global corporate citizenship (pp. 249–272). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Kolk, A. (2008). Sustainability, accountability and corporate governance: Exploring multinationals’ reporting practices. Business Strategy and the Environment, 17(1), 1–15.

KPMG. (2011). KPMG international survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2011. http://www.kpmg.com/Ca/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/Documents/CSR%20Survey%202011.pdf.

Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691–710.

Langley, A., & Abdallah, C. (2011). Templates and turns in qualitative studies of strategy and management. In D. D. Bergh & D. J. Ketchen (Eds.), Building methodological bridges. Research methodology in strategy and management (pp. 201–235). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Levi-Faur, D., & Jordana, J. (2005). Regulatory capitalism: Policy irritant and convergent divergence. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 598, 191–199.

Levy, D. L., Brown, H. S., & de Jong, M. (2010). The contested politics of corporate governance. Business and Society, 49(1), 88–115.

Levy, D. L., & Kaplan, R. (2007). CSR and theories of global governance: Strategic contestation in global issue arenas. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. Siegel (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of CSR (pp. 432–451). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MacLean, R., & Rebernak, K. (2007). Closing the credibility gap: The challenges of corporate responsibility reporting. Environmental Quality Management, 16(4), 1–6.

Maignan, I., & Ralston, D. A. (2002). Corporate social responsibility in Europe and the U.S.: Insights from businesses’ self-presentations. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3), 497–514.

Matten, D. & Moon, J. (2008). “Implicit” and “Explicit” CSR: A conceptual framework for a comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 404–424.

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media: The extensions of man. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. The American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363.

Moneva, J. M., Archel, P., & Correa, C. (2006). GRI and the camouflaging of corporate unsustainability. Accounting Forum, 30(2), 121–137.

Moon, J., Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2011). Corporations and citizenship in new institutions of global governance. In C. Crouch & C. Maclean (Eds.), The responsible corporation in a global economy (pp. 203–224). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nikolaeva, R., & Bicho, M. (2011). The role of institutional and reputational factors in the voluntary adoption of corporate social responsibility reporting standards. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 136–157.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2006). Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 66(1), 71–88.

Parker, C., & Nielsen, V. L. (2011). Explaining compliance: Business responses to regulation. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Perez-Batres, L., Doh, J., Miller, V., & Pisani, M. (2012). Stakeholder pressures as determinants of CSR strategic choice: Why do firms choose symbolic versus substantive self-regulatory codes of conduct? Journal of Business Ethics, 110(2), 157–172.

Rasche, A. (2009). Toward a model to compare and analyze accountability standards: The case of the UN Global Compact. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 16(4), 192–205.