Abstract

This article investigates corporate social responsibility (CSR) as an institution within UK multi-national corporations (MNCs). In the context of the literature on the institutionalization of CSR and on critical CSR, it presents two main findings. First, it contributes to the CSR mainstream literature by confirming that CSR has not only become institutionalized in society but that a form of this institution is also present within MNCs. Secondly, it contributes to the critical CSR literature by suggesting that unlike broader notions of CSR shared between multiple stakeholders, MNCs practise a form of CSR that undermines the broader stakeholder concept. By increasingly focusing on strategic forms of CSR activity, MNCs are moving away from a societal understanding of CSR that focuses on redressing the impacts of their operations through stakeholder concerns, back to any activity that supports traditional business imperatives. The implications of this shift are considered using institutional theory to evaluate macro-institutional pressures for CSR activity and the agency of powerful incumbents in the contested field of CSR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) has become a taken-for-granted concept within the Western society. Governments, consumers, employees, suppliers and many other groups have shaped the concept of CSR through their expectation that corporations will act responsibly in the conduct of their operations. Although the specifics may be contested (Waddock 2004; Banerjee 2007; Matten and Moon 2008), at the broadest level, these expectations are based on the need to align the social, environmental and economic responsibilities of business (e.g. Elkington 1997; Garriga and Melé 2004; Norman and MacDonald 2004). In other words, CSR is predicated upon the idea that business does not have a sole financial purpose, but a set of three core imperatives—economic, social and environmental—which guide decisions and activity, and which are equally valid and necessary within business. This is different from the business case for CSR (henceforth called the business case), which seeks to demonstrate how consideration of social or environmental concerns contribute to the financial position of the business (e.g. Friedman 1970; Johnson 2006; Porter and Kramer 2006).

Described as an ‘almost truism’ (Norman and MacDonald 2004, p. 243), the status of CSR as a set of taken-for-granted ideas within society, or institution (e.g. DiMaggio and Powell 1991; Tolbert and Zucker 1996; Scott 2001), has received little attention within the literature. This is an important oversight because institutional theory provides a powerful lens for helping us to explain how we come to understand and accept different attitudes and practices in a particular social context (Powell and DiMaggio 1991). In the case of CSR, there has yet to be any clear evidence of the existence of an institution, and if so, its form. Given that it is a relatively new idea for business and that its specifics are contested by the wide range of stakeholder interests (Mitchell et al. 1997; Cragg and Greenbaum 2002; Parent and Deephouse 2007), identifying its form is crucial to understanding future iterations.

This article therefore uses interviews with 38 CSR professionals in 37 different multi-national corporations (MNCs) based in the UK to investigate the existence of an institution of CSR within MNCs and its implications. Our findings suggest that unlike broader notions of CSR shared between multiple stakeholders (Crane et al. 2008b), MNCs practise a form of CSR that undermines the broader stakeholder concept. By increasingly focusing on strategic forms of CSR activity, MNCs are moving away from a societal understanding of CSR, which focuses on redressing the impacts of their operations through stakeholder concerns, back to any activity that supports traditional business imperatives. In other words, instead of providing an alternative model of business centred on profit and responsible conduct as equally valid and necessary business outcomes (Elkington 1998), their practices are turning CSR into a business innovation used to support profit generation. Whilst perhaps not surprising, it suggests that CSR is failing to redress the negative systemic problems associated with the dominant market logic. It is therefore failing in its objective to make business more responsible and accountable to society.

The article therefore has two main contributions to the CSR literature. To the mainstream literature, it contributes evidence of an institution of CSR and some of its key characteristics. To the critical literature, it provides evidence of a subtle but significant shift in how CSR is practised, sufficient to potentially undermine CSR. Given the power of MNCs within most countries to influence business practice, our research raises important questions about how the form of CSR they practise has the potential to influence legitimate CSR activity in the future. We use institutional theory to critically investigate CSR practices within MNCs and discuss some of their resulting long-term implications.

An Institution of CSR?

The small but growing literature linking CSR and institutional theory focuses mainly in two areas: macro-institutional pressures that influence firms to engage in CSR, and evidence of institutionalization. Studies focusing on macro-institutional pressures tend to investigate broad societal pressures on corporate engagement in CSR, and use these to demonstrate how CSR varies in particular contexts. They illustrate the influence of such things as high-impact industries (Jackson and Apostolakou 2010), deletion from social indices (Doh et al. 2010), health of the economy (Campbell 2007), or features of particular stakeholders, such as communities (Marquis et al. 2007), activist groups (Den Hond and De Bakker 2007) and governments (Gond et al. 2011) on corporate engagement with CSR activities. These pressures are often compared across contexts, such as national boundaries (e.g. Boxenbaum 2006; Doh and Guay 2006; Matten and Moon 2008), to illustrate why CSR varies in these contexts.

In essence, these contributions highlight the different ways in which other institutions, such as financial systems or governments, shape CSR within business. Business, however, is generally not considered to be an active participant in creating these pressures. They are implicitly depicted as passive pawns (Tempel and Walgenbach 2007) or cultural dopes (Giddens 1984; Creed et al. 2002) which receive and then respond to pressures for particular CSR activities coming from outside the organization. Those making exceptions to this theorize that in the absence of strong external pressures, managers will either adopt certain CSR-like activities to enhance the firm’s reputation or ignore it altogether (Beliveau et al. 1994; Campbell 2007). And whilst mainstream CSR literature recognizes the values-based approach, where business engages in CSR based on the values of particular employees (e.g. Maignan and Ralston 2002; Windsor 2006; Aguilera et al. 2007), it is underrepresented in the literature linking CSR and institutional theory. Thus, the existing CSR and institutional theory literature suggests that CSR is done either by passive firms pressured by stakeholders, or because it improves profitability.

Alongside institutional pressures for CSR, there is a great deal of evidence to suggest that CSR is becoming institutionalized within society. Whilst an exhaustive discussion of this literature is outside the scope of this article, there are many examples of the institutionalization of CSR as a society-wide concept. For instance, accidents and incidents, fraud, scandals and even problems with the existing global economic system have all been linked back to the wider responsibilities of business to society. For instance, BP claiming that their response to the Deepwater Horizon spill was a model of CSR (Macalister 2010; Mason 2010), or making banks responsible for their financial, social and environmental responsibilities by taxing them to fund social initiatives (i.e. Robin Hood Tax) are just two examples among the many that suggest strong issue relevance of CSR within society.

Meyer and Rowan (1977, p. 347) further suggest that evidence of institutionalization is present in the development of trained professionals, modification of market tools, changes in public opinion and codification into law. For instance, there has been an explosion in ‘training’ such as practitioner workshops and seminars, specialized auditor training for awarding certifications, such as ISO14001, and specialist Master and PhD programs dedicated to CSR, including a body of literature on CSR education (e.g. Matten and Moon 2004; Moon and Orlitzky 2010). CSR has also become the focus of many market instruments such as reports (e.g. Owen and O’Dwyer 2008), shareholder resolutions (i.e. ECCR 2006) and investment activities (e.g. Consolandi et al. 2009). In terms of public opinion, salient CSR issues are becoming better known and receiving wide-spread support, such as the need for urgent action on climate change (e.g. Curry et al. 2007; European Commission 2008). Citizens are also becoming more involved in social change projects, as evidenced by a vast increase in the number of NGOs focused on social and environmental issues (e.g. Arenas et al. 2009). Codification of CSR into law is dramatically increasing with a number of countries putting in relevant legislation. Examples include the UK Companies Act (2006) and the Climate Change Act (2008), the Canadian Sustainable Development Act (2008), the US Sarbannes-Oxley Act (2002), the Government of Mauritius Finance Act (2009), non-financial reporting legislation across Europe, such as Green Accounts Act, Law no. 975 (1995) in Denmark, environmental and labour laws in most countries, and international standards on human rights and labour through bodies such as the UN and the ILO. Clearly, these practices demonstrate the institutionalization or ‘almost truism’ (Johnson 2006) of CSR within society.

This agreement on the existence of CSR also extends to how it is defined. Crane et al. (2008b, pp. 7–8) identify six core characteristics that are common across most definitions and studies of CSR. These are that one, CSR is primarily voluntary; two, it focuses on internalizing or managing externalitiesFootnote 1 of the product or service provided; three, it has a multiple stakeholder orientation which means that groups other than the business are important; four, there is a need for alignment of social, [environmental] and economic responsibilities in routine activities and decision-making; five, it must be embedded in both practices and values; and six, it is beyond philanthropy, focusing on operational considerations. These characteristics form the basis of a shared understanding between the multiple stakeholder groups represented in the literature, such as government, communities, employees, suppliers, NGOs, investors, religious groups, academics, etc. By identifying these six areas of consensus within the literature, Crane et al. (2008b) argue for a common and shared understanding of CSR at a societal level, such that when the term is used, some or all of these characteristics are implied.

Therefore, research linking CSR and institutional theory paints a very convincing picture of an institution of CSR, set around a shared definition, and created by a broad group of stakeholders at the societal level. However, if corporations are so powerful ‘that their decisions affect the welfare of entire states and nations’ (Stern and Barley 1996, pp. 147–148), then the form of CSR they practise is likely to have important implications for actors within and outside the marketplace. Therefore, institutional theory, besides helping us to explain the strong pressures to engage in CSR, can also help us shed light on powerful actors, such as MNCs, and their role within the contested field of CSR.

Institutions and Contested Practices

Institutional theory tells us that institutions are powerful patterns of social action that influence how we think and act in relevant social contexts (e.g. Meyer and Rowan 1977; Granovetter 1985; March and Olsen 1989; Scott 2001). According to DiMaggio and Powell (1983), there are three mechanisms by which attitudes and practices become increasingly homogenous within a social context: coercive, mimetic and normative isomorphic pressures. Coercive pressures result from both formal and informal influences on organizations to reflect the cultural expectations of society. These include codification of the law and other forms of regulative pressure, such as NGO campaigns, government policy and media coverage. Mimetic pressures stem from organizations working to model themselves or their practices on others. This is often due to uncertainties in their operating environment and can include such things as changes in consumer preferences, vague or absent government regulation, or negative publicity. Finally, normative pressures result primarily from the professionalization of certain disciplines. As members of a discipline come to standardize the skills and cognitive base required to be members of that profession, they create the ‘legitimacy for their occupational autonomy’ (p. 152). These three pressures help us increase homogeneity of meanings and practices associated with relevant institutions (e.g. Scott 2001) and are a key mechanism of the institutionalization process.

During institutionalization, a set of shared meanings are also established at the core of the institution. This is called a central logic and it acts as ‘a set of material practices and symbolic constructions—which constitutes organizing principles and which [are] available to organizations and individuals to elaborate’ (Friedland and Alford 1991, p. 248). Within the relevant social context, it is possible to identify distinct, often competing logics, as well as the dominant logic within the field (e.g. Bacharach et al. 1996; Lounsbury 2002; Thornton 2002). In the context of business, the dominant logic tends to be called the market logic and focuses on agency relationships that seek to optimize cost–benefit calculations of economic transactions with the goal of maximizing financial gains (Dijksterhuis et al. 1999; Thornton 2002; Glynn and Lounsbury 2005). This can be compared with alternative logics (such as those related to CSR) to illustrate fundamental differences in the philosophy underpinning relevant values and practices of business institutions.

Whilst these forces of constraint and conformity described above are strong {Scott 2001; Hoffman 2001; Meyer and Rowan 1977}, actors play an important role in the maintenance and change of institutions. It is increasingly recognized that markets and other forms of organizational activity are contested (Lounsbury 2001; Levy 2008a; King and Pearce 2010). Incumbents, around whom activity tends to revolve (McAdam and Scott 2005, p. 17), struggle with challengers (e.g. Beckert 1999) to construct the structures and processes of institutions (Levy 2008b). Incumbents seek to maintain the institutional structures that maintain their advantage, whilst challengers work to realign the structures to improve their position within the institution (Knight 1992). Both groups seek to advance their position through the use of available resources such as power or social skill (Fligstein 2001; Lounsbury and Crumley 2007; Levy 2008b). By collaborating and competing over different aspects of the field, actors constantly create and shape relevant institutions within a particular social context (Fiss and Zajac 2004). Thus, the resulting institution represents the outcome of ‘negotiations’ between interested parties (Fiss et al. 2011). Agency therefore takes a more central role in this area of the institutional theory literature, where actors not only compete for control over institutional structures and processes, but are also constrained by existing arrangements (Giddens 1984; Friedland and Alford 1991; Thornton and Ocasio 2008). Agents therefore perform a critical function within contested fields by constantly creating and recreating institutions in an attempt to improve their relevance within the social context (Fligstein 2001).

With regard to CSR, although a consensus exists on its definitional components (Crane et al. 2008b), there remain many highly contentious areas within the field, such as where corporate responsibility ends and individual or governmental responsibility begins (Dunning 1998; Matten et al. 2003; WBCSD 2005). Given this high level of contestation within CSR (Waddock 2004; Banerjee 2007; Matten and Moon 2008), we would expect both incumbents and challengers to be very active in shaping its structures and processes. Since institutional theory is able to explain the strong macro-institutional pressures resulting in the institutionalization of CSR, and also theorizes agency in contested fields, it is a particularly strong lens from which to investigate CSR practice within MNCs. However, given the concern of some CSR scholars as to whether we have ‘been spending our efforts promoting a strategy that is more likely to lead to business as usual, rather than attacking the more fundamental problems’ (Doane 2005, p. 28), it is necessary to employ a critical perspective in our investigation of CSR practice.

CSR: A Critical Perspective

A great deal of study has been done to investigate different aspects of CSR such as what it is (e.g. Carroll 1979; Wood 1991), how to do it (e.g. Nattrass and Altomare 1999; Cramer 2005), what factors affect its degree of integration within business (e.g. McWilliams and Siegel 2001), how to control it (e.g. Husted 2003), who should be involved (e.g. Donaldson and Preston 1995), how to communicate it (e.g. Morsing 2003), how to formalize it (e.g. Fransen and Kolk 2007), how it relates to the wider society (e.g. Donaldson and Dunfee 1994; Swanson 1999), and specific elements such as fair trade (Davies 2009).

Although popular, the business case for CSR (e.g. Schaltegger and Wagner 2006; Zadek 2006; Husted and Allen 2007) focuses on how consideration of social or environmental concerns contribute to the financial position of the business (e.g. Friedman 1970; Johnson 2006; Porter and Kramer 2006). Whilst these may result in positive outcomes for society, the main goal is to protect the corporation. A recent review of the business case literature emphasized CSR as creating value for business in four ways: reducing costs and risk, creating competitive advantage, building reputation and legitimacy, and generating win–win–win outcomes (Kurucz et al. 2008). Thus, the priority is on using CSR to create value as defined by the dominant market logic, such as improved competitive positioning or profitability. What separates the four types is the extent to which benefits for other groups are ancillary or designed into the outcome.

This is no different to traditional business practice where any issue, whether social/environmental, or something else such as engineering specifications, would be assessed according to how well it supports traditional business concerns such as profitability of the firm. Thus, the business case can therefore not be considered CSR because social and environmental issues are not aligned with economic in a triple bottom line (Elkington 1997). This distinction between CSR and the business case for CSR is important because it highlights substantially different underlying philosophies for business engagement with social and environmental issues. As this article will show, the differentiation in emphasis is crucial when applied in practice.

A growing sub-section of the CSR literature is raising concerns about mainstream ideas, pointing to a need for more reflexive, critical perspectives on CSR. This, according to Blowfield (2005, p. 173) is one of the core failings of CSR. He argues that having yet to develop the means for internal critique, the field of CSR is ‘unable to recognize its own assumptions, prejudices and limitations’ (p. 173). In response to these and other similar concerns, the critical CSR literature has advanced three core issues. The first seeks to redress the implicit Western bias in CSR research, where scholars challenged the universality of its foundational concepts by demonstrating different conceptualizations in different countries (Blowfield and Frynas 2005; Prieto-Carron et al. 2006; Scherer et al. 2009; Idemudia 2011). Supported by suggestions that ‘CSR tools’ used by business did not function effectively outside Western countries (Kaufman et al. 2004; Newell 2005), these contributions raise important questions about the meaning of CSR and its applicability in different cultural contexts.

Stemming from the first, the second core issue of critical CSR literature questions the role of business in society. As Bies et al. (2007, p. 788) point out, there is no disputing the fact that corporations sometimes act as agents of social change. However, concerns are mounting about the implications of corporations taking on the activities of governments or individuals, in their role as citizens (Matten and Crane 2005; Moon et al. 2005). Called ‘corporations as political actors’ (Scherer and Palazzo 2007; Detomasi 2008), the said research focuses primarily on instances of corporations acting as change agents, such as in the provision of healthcare (see for instance Academy of Management Review 32(3)) and conceptual work to identify a new theory of the firm that helps to explain corporations acting outside the marketplace (Matten et al. 2003; Scherer and Palazzo 2007).

A third issue has recently been indentified as vital to continued improvement of CSR research and application within business. Banerjee (2007, p. 167) and Devinney (2009, p. 54) have both emphasized the need for a much more critical investigation of specific CSR practices, their outcomes and the broader implications these have for society. They argue that focusing solely on CSR as a “‘good” alone’ (Devinney 2009, p. 54) is somewhat naïve and does not take into account the complexity of motivations and activities that constitute a commitment to CSR. Thus, critical explorations of practice are needed to create a more holistic picture of the reality of CSR as part of the daily activities of corporations.

Therefore, whilst it is becoming increasingly accepted that corporations are ‘part of the authoritative allocation of values and resources’ in society (Crane et al. 2008a, p. 1), the form and implications of these activities have yet to be fully explored (Moon 2002; Moon and Vogel 2008). This research therefore uses the frame of institutional theory to look critically at the specific practices of CSR conducted within MNCs. We investigate the extent to which these practices may or may not represent an institution, and the resulting implications of these findings for business claims about social responsibility.

Methods

Identifying the form of an institution within corporations requires speaking to actors involved in the institutionalization process to explore their interpretations of relevant values and practices. Adopting an exploratory, interpretive approach to investigate institutions is particularly appropriate given that institutions are by definition patterns of social action with high resilience, but are subject both to context and agent interpretations (e.g. Berger and Luckmann 1967; Burrell and Morgan 1979; Morgan 1980). It is also appropriate for the particular study as little is known about whether an institution of CSR exists and the role played by corporations.

To capture the experiences and interpretations of relevant actors, a semi-structured interview method was used (e.g. Holstein and Gubrium 1995; Strauss and Corbin 1998; Keats 2000). The purposive sample (e.g. Baker 2002; Saunders et al. 2007) consisted of 38 professionals responsible for the development and implementation of CSR strategy within their organizations. By targeting individuals with this expertise, it was possible to better understand how actors in a significant position to influence CSR within organizations perceive and practise CSR, and by comparing accounts, to determine areas of similarity and difference in the underlying philosophy and supporting structures. Thus, it was possible to identify the form of CSR as practised by business.

Sample

To ensure participants were knowledgeable in the practice of CSR, they were drawn from a list of the largest companies (according to sales revenue) in the UK according to the FAMEFootnote 2 database. We sorted companies according to annual sales revenue and then selected for companies who operated in more than three countries worldwide to ensure their MNC status, were headquartered in the UK to control for home country effects, and who were publicly traded on the London Stock Exchange to ensure the best possible availability of public information. Selecting the largest companies in the UK allowed us to identify professionals in companies large enough to have relatively mature CSR experience and practice (Langlois and Schlegelmilch 1990; Maignan and Ralston 2002), ensuring insight into a number of cycles of CSR activity and the history of its development within the organization. 67 letters were sent to companies fitting these criteria, with 24 positive responses, resulting in a response rate of 36%. During interviews, a snowball sampling technique was also used, resulting in an additional 14 responses for a total of 38 interviews within 37 different MNCs with professionals responsible for developing and implementing CSR strategy within their organizations. These companies represented a range of industries, being more heavily represented by natural resource and retail companies, but also by those in the construction, manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, tourism, telecommunications, public utilities and consulting industries. As illustrated in Table 1, these professionals came from a range of functions such as PR, security and investment. They also represented a range of backgrounds from engineering to biology to communications.

Before the interview, all publically available documents related to their CSR activities were read to provide additional information about how the company presented itself with regard to its CSR activities (Coupland and Brown 2004; Bondy et al. 2008). We focused on company-created documents including their website, company reports, press releases, codes of conduct/ethics, performance indicators, declarations of compliance, case studies, etc. These were used to prepare for interviews and to support interview data. 19 interviews were conducted in person and 19 by phone. The interviews lasted anywhere from 25 to 93 min, with an average of 56 min of discussion time. Only one interview lasted 25 min and two approximately 90 min. Participants were asked to discuss five broad topics: motivations/drivers for engaging in CSR, major implementation techniques used, impacts of organizational and other forms of culture on these processes, stakeholder feedback on development and implementation, and lessons learnt during implementation. These broad topics were used to direct the conversation on critical aspects of internal and external influences, tools involved in developing CSR within their organizations, conflicts and opportunities around CSR and how they were addressed, and how this informed their understandings of CSR as an organization. Issues of validity and reliability were addressed at the data collection stage by using digital recordings and notes taken directly following each interview that included non-verbal cues or other pertinent information on the interview process itself (e.g. Miles and Huberman 1998; Silverman 2001; Saunders et al. 2007). The sample is therefore broadly representative of CSR practices in the publicly traded MNCs in the UK.

Analysis

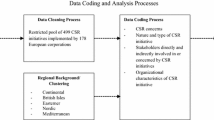

The constant comparative method was used to analyse the data (Gerson and Horowitz 2002; Langley 1999; Miles and Huberman 1998; Silverman 2001; Spiggle 1994; Strauss and Corbin 1998). Every word mentioned on transcripts, and every theme captured in notes went through three stages of coding to ensure that all data were incorporated, and that resulting conclusions represent the interpretation presented by participants. The transcripts were broken down into three main groups based on when the interviews were conducted. The first group consisted of 10 interviews, the second 15 and the final group of 13. All the interviews were conducted within 4 months, with no significant changes in the institutional environment within the UK such that there were no time-based effects on the analysis of data.

The first type of coding involved categorizing (open coding) (Spiggle 1994) the data into thematically relevant categories. Each transcript was coded based on the themes identified within. These themes and related text were pasted into an Excel spreadsheet. Every word uttered was given a theme and included in the spreadsheet in this way. For each subsequent transcript, the themes were identified within the transcript itself, and then compared (Lincoln and Guba 1985), resulting either in the maintenance of the thematic label and addition of new text, the modification of the thematic label to incorporate similar text, or the creation of a new thematic label signifying a fundamental difference in the nature of the theme being discussed (Glaser and Strauss 1967). Figure 1 presents a small selection of these spreadsheets with each shade representing a different group of transcripts so that information could be traced back to the original coding if necessary.

Two other overlapping forms of coding, abstraction and dimensionalization were employedFootnote 3 (Spiggle 1994; Strauss and Corbin 1998). Using abstraction, themes were grouped by similarity of ideas allowing movement from concrete to more general and theoretically useful themes. These higher-order themes were then further abstracted (using axial coding) to link categories together hierarchically so that more general themes included relevant sub-themes (Charmaz 2000). This resulted in fewer higher-order categories and their relevant sub-categories, upon which their dimensions could be identified and analysed. Also called the ‘charting technique’ (Ritchie and Spencer 2002), the two opposing end points of higher-order themes were identified and placed on a continuum. All relevant data were then used to populate the continuum so as to generate rich, thick characterizations of the properties of these categories (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Figure 4 illustrates an example of how concrete data at the categorization stage were then combined into categories and sub-categories to further abstract and dimensionalize the two higher-order concepts of ‘start of stakeholder dialogue’. This concept was then further abstracted into Phase 2 of the overall process of CSR engagement identified by participants and illustrated in Fig. 3.

Following categorization, abstraction and dimensionalization, the resulting group of hierarchical themes and their rich characterizations were then integrated to generate ‘complex, conceptually woven, integrated theory; theory which is discovered and formulated developmentally in close conjunction with intensive analysis of data’ (Strauss 1987, p. 23). Although this process began with abstraction and dimensionalization, these categories were further refined to result in a model representing the process by which MNCs develop and implement CSR strategy within their organizations.

Each of the three groups of transcripts underwent categorization, abstraction and dimensionalization separately and then together. At the end of each round of coding for these groups, they were also coded visually according to the ‘hierarchy’ or process that was identified in the analysis. For example, the first group of 10 interviews went through the three types of coding using an Excel spreadsheet (light grey colour on Fig. 1). Themes were identified and modified as necessary to accurately reflect all data. Once higher-order themes and their characterizations were identified in the first group, these themes were transferred to a visual coding system on flip chart paper to see how the themes fit into the overall process of CSR engagement as iteratively identified through the data. This pattern of coding themes in detail on Excel and then coding higher-order themes on paper continued for each of the three sets of transcripts until all data were included. The results of visual coding are represented in Fig. 2.

The analysis illustrated in Figs. 2, 3, 4 and Table 2 represents the process by which participants within their MNCs went about making sense of and implementing CSR. These patterns or practices therefore reflect the form of CSR within these organizations and hence a form of the institution of CSR as practised by them.

Results

The data demonstrate clear evidence of an institution of CSR as practised by MNCs. Rather interestingly, these companies indicated strong coercive and mimetic pressures to demonstrate some form of general CSR engagement, but did not find normative isomorphic pressures to be significant. They also demonstrated significant agency in determining how to respond to these pressures for CSR. By increasingly working to align CSR activities with core corporate strategy, these MNCs undermined the multi-stakeholder concept of CSR identified by Crane et al. (2008b). Starting with the characterization of an institution of CSR within MNCs, these results will be discussed in more detail in the remainder of this section.

Isomorphism in the Form of CSR Practices Within MNCs

Whilst not homogenous, there is a significant degree of similarity in approach and execution of the systems, processes and activities utilized by these organizations in the name of CSR. This level of isomorphism, as demonstrated in Fig. 2, provides evidence of the form of an institution of CSR within MNCs. In other words, this figure represents the sum total of discursive work within the MNCs to define CSR, their responses to institutional pressures and increasing institutionalization of CSR within society, as well as their own agenda related to CSR, reflected in their practice. Since institutions are observable through the structures and practices associated with them (Scott 2001; Zilber 2002; Hensmans 2003), Fig. 2 thus represents a form of the institution of CSR as practised by MNCs.

These practices, herein called the CSR institution, were found to occur primarily in phases of activity, where one tended to precede each other as work conducted in one phase was needed for the next. The CSR institution is therefore organized into six phases: one, research—where companies identified their existing CSR meanings and activities and looked into competitor activity; two, strategy development—where they designed the form of their CSR commitments including details on how it will be implemented; three, systems development—where they created or amended supporting organizational systems and relationships along with commitments made; four, rollout—where strategy and systems were presented to particular groups and full scale implementation began; five, embedding, administration and review—where most of the day-to-day implementation activities occured with an emphasis on the cycle of initial implementation to embedding to review of progress; and finally six, continual improvement—where the strategy and supporting structures are revised given the feedback as obtained in phase five. Each interview participant indicated organizational engagement in each of the six phases, demonstrating full agreement on the existence and importance of each phase in the figure. Differences occurred at the level of detail, such as the specific timing of the phase relative to others, the degree of overlap with other phases, and in the detail of how any particular phase was enacted. Examples of differences in detail are represented in Figs. 3 and 4 and will be discussed in more depth later in this section.

Referring to Fig. 2, some activity did not occur in any one phase, but was constant throughout more than one. These activities tended to act as support for the main body of work and included such things as changes to different aspects of governance or aligning institutional pressures for CSR activities with the specific context and agenda of the organization. These were separated to form two of three parallel processes (Rijnders and Boer 2004) that support the implementation of CSR activities within the MNCs.

The first and main supportive process is the Substantive Process, illustrating clusters of activity surrounding key decisions and actions within the phase. These are represented by light grey boxes which denote decisions and actions that are typically conducted at roughly the same time and in no particular order of completion. The second supportive parallel process, Process Management/Governance, is composed of supporting governance structures that run parallel to the core activities in the Substantive Process. They are depicted as arrows in the middle third of the figure, and appear roughly at the stage on the CSR institution in which their involvement becomes crucial. The third parallel process, Diffusion and Integration, refers to supporting activities to communicate and bring the activities in the Substantive Process in line with existing organizational practices. It is composed of lines along the bottom third of the figure.

Supporting each of the phases is a detailed set of activities and associated meanings that break each phase into its constituent parts. This more descriptive level details the key decisions, activities and sub-processes identified by participants, how they are utilized within the business and the purpose of these activities within the CSR strategy. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate this level of detail and similarity in approach to developing and implementing CSR strategy. With each additional level of specificity represented in these Figure and Table, the level of agreement on practices is lower. To illustrate the point, Fig. 3 focuses on the strategy development phase where most participants mentioned most of the bullet points listed but not all. For instance, each participant mentioned the need to identify why the organization was engaging in CSR, which for some was to act as an organizing principle, and for others to act as a moral compass. Some did not consult experts. In fact only 15 of 38 participants consulted outside experts, as many had hired expertise in-house. Also, Fig. 4 indicates that in starting stakeholder dialogue every participant discussed the importance of stakeholder dialogue, but not all participants mentioned reducing the knowledge gap. This particular theme was mentioned by eight of the 38 participants. Similarly, 24 mentioned concerns around creating realistic expectations with key stakeholders. However, each theme contributed to the cluster of activity, in this case the key aspects of designing a draft strategy, which were then aggregated in the institution of CSR (Fig. 2). Therefore, it is possible to say that every participant mentioned each item on Fig. 2 but with varying degrees of detail and importance associated with them.

Figures 2, 3 and 4 demonstrate clear evidence of the form of CSR within MNCs. Thus, these figures and Table answer the main research question: does an institution of CSR exist within MNCs, and if so, what are some of its key characteristics? Given the strong similarity in practices, they provide concrete evidence of the structures and activities supporting an institution of CSR within MNCs. This institution was found to be significantly influenced both by macro-institutional pressures and by agency.

Macro-Institutional Pressure for CSR Within MNCs

Macro-institutional pressures were significant in leading these MNCs to initially engage with CSR. In support of the macro-institutional literature on CSR discussed earlier, the data clearly suggest that this form of CSR has been influenced by two of the three types of isomorphic pressures identified by DiMaggio and Powell (1983): coercive and mimetic. Normative pressures were not found to be influential in the form of CSR practised within MNCs.

Coercive Isomorphic Pressure from Society

Whilst things such as industry (Jackson and Apostolakou 2010) or health of the economy (Campbell 2007) were found to influence business activity on CSR within the literature, these corporations were primarily influenced to engage in CSR because of coercive stakeholder pressure. Signals from core stakeholders indicated the importance and inevitability of responding to CSR. Three stakeholder groups were particularly influential: government, customers and investors (see Table 2). These illustrative quotes signify the importance of stakeholders in pressuring corporations to engage in CSR. Because these corporations faced similar pressures and what they felt was a lack of leadership in government (e.g. NR3, PS3, MF4, etc.), they relied heavily on each other to identify how to manage their CSR involvement.

Mimetic Isomorphic Pressure Resulting from Competition

Most MNCs were quite open about tracking the activity of their perceived ‘CSR competitors’Footnote 4 (e.g. NR4). These corporations observed the justifications and activities of their CSR competitors, to both map the CSR marketplace and identify activities to emulate. For some this was symbolic to ensure they did not fall behind the competition,

I constantly check [competitor]’s website to see what’s new and what’s in their reports. They are the leaders in our industry and we don’t want to be seen to fall too far behind…but our CSR activity mustn’t cost anything, it mustn’t commit the company to anything and it mustn’t expose the company to any risk…it mustn’t hold us hostage to making commitments that could then be thrown back at us and said “ah you failed on this” (TR1)

For most of the MNCs, this was to keep pace with competitors,

Some of it has been driven by my neighbour. My competitor is doing it and so I better be seen to be making the right strides (CN2)

For a few of them, this was to become CSR leaders themselves.

…but actually doing an awful lot more in terms of walking the talk, setting out to do good rather than just about not doing harm. And that’s been, a very very conscious effort…and I think the difference that that’s made is rather than just having an environmental policy which is what a lot of our competitors have, is that we’ve actually got an environmental and social diary that can demonstrate what we’ve done (SP1(P))

Every MNC in the research engaged in some degree of tracking their CSR competitors. Some did so through participation in collaborative or best-practice-sharing groups such as the Ethical Trade Initiative, UN Global Compact or industry bodies (e.g. NR3, NR6 and RT9). However, most focused on their competitors’ CSR reports and policies to identify changes in CSR activity so as to improve their own practice. For instance, mimicking or translating (Czarniawska and Joerges 1996; Creed et al. 2002; Zilber 2006) the reports of others was a way to reduce the uncertainty surrounding content of the report, and to minimize the learning curve that was necessary to get the report out in the minimum amount of time. TR1 for instance ‘constantly checked the reports for [CSR leader 1] and [CSR leader 2] to help guide the creation of our own report. It is a real time and money saver because we don’t have to pay a consultant to do it for us’.

Codes/policies were a far more interesting and competitive area amongst the corporations, demonstrating the extent to which they tracked each other’s practices. Most kept a very close eye on the content of their competitors’ codes to ensure that the commitments and wording of their own code put them in either a competitive or leadership position (e.g. PS1, RT4, NR4).

[there was] firstly a recognition that we needed a set of minimum ethical criteria, but also I think recognition that it was becoming best practice amongst large PLCs that you should have a written code of business conduct or similar. And actually, we were not particularly proud about these things. We took a number of other company’s documents and filleted the best out of them for us and then put one or two [MF2] pieces into it. But it’s quite unashamedly ripped off from similar companies (MF2)

This type of mimicry and translation occurred in a vast range of areas, such as in designing of online training schemes for employees, in identifying key stakeholders, in determining relative percentages of sales to charitable turnover, or in designing and implementing employee volunteering initiatives such as building a school. Through collaborations, reports and codes/policies, MNCs regularly scanned for perceived improvements in CSR practice in other corporations, and strove to include a variation within their own operations. In this way, justifications, structures and practices continued to converge on a similar form of CSR across MNCs.

Agency Effects on the Form of CSR Within MNCs

However, agency also played an important role. This was clear both in the justifications for engaging in CSR and for the continually changing shape of CSR activities within MNCs.

Where historically companies were happy to define their responsibility to society as largely philanthropic (e.g. Davis 1960; Sethi 1975; Brammer and Millington 2003), and based on stakeholder issues (Mitchell et al. 1997; Phillips 1997; Laplume et al. 2008), their definition was changing. These MNCs believed that win–win situations were possible by engaging in CSR and were working to ensure their CSR activities were based less on institutional pressure and more on strategic alignment. In other words, they felt and responded to institutional pressures for some form of CSR more generally, but were very much in charge of determining the specific CSR activities considered to be legitimate within their organizations. This allowed them to focus on investing in CSR issues relevant first for business concerns and secondly stakeholder issues. For instance, RT1 indicated that, in the past, their relationship with society had been based on donations, typically of money. However, as the meaning of CSR within society shifted towards an equal emphasis on social, environmental and economic considerations, RT1 also began to shift their own understanding of CSR so as to not only reflect these changes, but also to ensure alignment with the business agenda.

So now, why do we want to do this? Well if I’m talking to the finance director it’s because it’s cheaper and if I’m talking to [professors of business ethics], it’s because it’s the right thing for RT1 to do. So what drives us is a combination of the two of those things (RT1)

Therefore, not only did they begin to absorb broader institutional justifications for CSR, but made clear the importance of their own agenda in justifying CSR activities. They also went further to describe their rationale for selecting strategically relevant activities, when there was institutional pressure for something else.

…if you look at an oil company like Shell, they might be in the Philippines. Now there’s been this horrific mudslide, so you can understand why a company like Shell might want to be seen as being supportive, helpful to that particular tragedy. It’s more difficult to see why [RT1] should become involved because we don’t have any outlets in the Philippines, we don’t have a presence there. We might have one or two small suppliers but really we don’t have a footprint there…but if you look at [RT1], why is breast cancer our number one charity above anything else? Answer because 79% of the people who work for [RT1] are women, 83% of our customers are women and breast cancer is the thing that most concerns them, so therefore we are absolutely seen to be in line with their issues (RT1)

Therefore, whilst responding to changes in the CSR logic within society such as the need to ‘do the right thing’, RT1, like all other MNCs in the study, ensured that their business agenda was paramount in justifications for CSR activity, and in many cases overshadowed social and environmental considerations. By doing so, they contributed to a rhetoric that focuses increasingly on the importance of strategically aligned activities and thus economic priorities, but that downplayed other CSR attributes such as managing externalities or impacts.

Agency was also evident in the practices that MNCs used to engage in CSR. Corporations who wanted to become leaders in CSR recognized the power and opportunity available to them by differentiating themselves in the marketplace based on CSR issues.

Now I do work with a couple companies that have adopted external codes because they see them as something of a competitive advantage. They can set themselves apart as either a more sustainable company or ethical company through their adoption of those things. They are using it as a positioning tool to kind of say “the adoption of this is going to lead us to some big shift in how we operate and could even lead us to re focusing the company on a different path” (CN2)Footnote 5

With companies constantly tracking and translating each others practices, there was a substantial tension between differentiating oneself from competitors in a CSR sense, and wanting to signal to stakeholders that CSR activities were taking place. Focusing on strategically aligned CSR initiatives allowed MNCs to do both. They could claim they were responding to stakeholder pressure for CSR but could differentiate themselves by focusing on particular initiatives that were relevant to their key stakeholder groups, as opposed to operational impacts. They could then brand or market these initiatives as something different to their competitors but signal an overall emphasis on acting responsibly.

This however had the effect of moving CSR away from a relatively equal emphasis on social, environmental and economic imperatives to a business case approach where social and environmental issues are enacted only where they support more traditional business imperatives. In this way the social and environmental concerns were made subservient to financial issues, supporting a market but not a CSR logic.

Again codes/policies provide the clearest example of this type of strategic activity. Whilst many companies were investigating the possibility of developing a ‘global’ code within their organization (e.g. NR3, MF4, PS1), this was considered by many to be very difficult in practice, tantamount to the ‘holy grail’ (PS2). However, when NR4 claimed to achieve it in 2006, all eyes were on them to see whether the code would deliver on its stated worldwide application. In describing how the code was achieved, NR4 explained:

There were polices on these topics all over the globe in various forms, some of them in somebody’s desk. This is the first time these topics were explored on a global basis and made directly applicable to every employee no matter where they worked. So really it was new drafting and looking at what existed and taking what we wanted from that but really writing in a form that was understandable by employees. So as those policies were developed, as the code developed, it was really thinking through, what as the company, do we expect from our employees as minimum behaviour. It really is meant to be very clear for the first time in all of these areas what individual employees can do to actually help achieve these sort of broad group values that we talk about (NR4).

Therefore, they claimed to create a code where the content was specific enough to reflect the expectations of key stakeholders around CSR commitments, but that was vague enough as to be applicable to all employees in all operating locations worldwide. Other MNCs were suspicious of this claim, questioning the ability to develop a truly global policy. For instance, PS3 indicated that ‘I think [NR4] has finally managed to have a single code of business conduct [gives look indicating doubt]. So, maybe in time there may be an ability to have one but at the moment we need to have separate ones for [our businesses in other countries]’ (PS3). And whether suspicious of NR4s ability to create this type of code, other MNCs within their sector and/or wanting to take a leadership position on CSR, closely examined the contents of the code. Since then, a number of the larger MNCs have created similarly structured and worded codes (e.g. RT4, NR9, CT1), and NR4 was invited before the House of Lords to talk about their policy developments with a view to creating an industry standard (NR4). NR4’s practice related to the code therefore became the benchmark for the industry and other CSR leaders. Their activity shifted the way that MNCs thought about codes and their applicability, as well as how they were written and presented to employees.

Thus, where stakeholders contributed to a generalized coercive pressure to ‘do something’ with regard to CSR, they had little influence over specific CSR activities within the MNCs. As suggested by the stakeholder literature (Freeman 1984; Mitchell et al. 1997; Phillips 2003) MNCs were very much in control of determining which stakeholders to select. The data suggests that they were also in control of the specific activities they would undertake in the name of CSR. Being in control of selecting both relevant stakeholders and specific activities to redress stakeholder concerns further entrenched their power with regard to CSR and thus their position as field incumbents. In this way, they could protect the existing structures and processes associated with the market logic from which they generated their power and wealth. Changes they made for stakeholders, or challengers, could be (and often were) superficial and did not impact the central operating principles of the organization.

Therefore, the similarity in form of CSR practised within MNCs (Fig. 2) not only resulted from institutional pressures for CSR activity and agency designed to gain advantage from CSR differentiation, but also suggests a shift in broader notions of legitimate CSR from stakeholder-centric to strategy-centric activity.

Implications—Power and Politics of the CSR Agenda

Clearly, MNCs are shaping CSR through their practices. If we look back to the comment about the power of MNCs being so great as to influence entire nations (Stern and Barley 1996) it is possible to see how being field incumbents provides them with disproportionate control over how the institution is shaped (Friedland and Alford 1991; Knight 1992). As indicated above, in the absence of strong institutional pressures, managers will act opportunistically to either ignore or shape CSR in ways favourable to themselves (Beliveau et al. 1994; Campbell 2007; Bondy 2008). Since MNCs have the ability to select who their stakeholders are (e.g. Freeman 1984; Donaldson and Preston 1995; Phillips 1997), and the selection is not linked to the impact of their operations but to the power, urgency and legitimacy of the stakeholder claim (Mitchell et al. 1997), their influence in terms of specific CSR activity, can only be counteracted by similarly powerful stakeholders (Scherer and Palazzo 2007). Many might argue that governments are also field incumbents with sufficient power to counteract and control business. In the case of MNCs this is however made difficult by their transboundary nature (Linneroth-Bayer et al. 2001). In fact, their increasing involvement in the provision of services to citizens such as infrastructure development, ensures and enhances their access to societal resources (Crane et al. 2008a) and thus their power base within society. Therefore, whilst stakeholders are able to apply sufficient pressure to ensure corporate engagement with CSR as a business issue, few are sufficiently powerful to enforce a particular form of CSR on MNCs. MNCs are therefore in a unique position to shape CSR in ways beneficial to them. By ignoring stakeholders when it makes business sense to do so and therefore protecting their privileged position in the field, they risk violating key foundations of the CSR concept such as its stakeholder orientation and balance of social, environmental and economic impacts.

The nature of the practices is also telling. To implement their CSR strategies, these MNCs primarily used tools, frameworks and processes that already existed for many years within their businesses. Having been designed for the purposes of generating profits, these systems were then modified to include CSR. For instance, MNCs use the annual financial reporting system as the basis from which to generate reports on CSR performance. Using similar reporting styles, structures, types of measurements etc., CSR data are created to fit within the time frame and structure of financial reports. However, the suitability of this process for CSR is questionable given the differences in time horizons of financial and CSR data, and the difficulties involved in identifying social and environmental impacts, creating mitigation activities and measuring performance (e.g. Global Reporting Initiative 1999; Davenport 2000; Gray 2001). In essence, a financial reporting system is not well designed to capture and report on CSR data. But MNCs use these and other processes regardless of their appropriateness for incorporating CSR. Instead of developing new tools and practices suited to CSR activities, they largely co-opted (Selznick 1949) existing business practices to support CSR activities. Thus, the incumbents used their position of authority to determine how CSR would be incorporated.

The data therefore suggest the existence of an institution of CSR within MNCs and some of its observable characteristics. However, this institution represents a shift in meaning of CSR away from stakeholder concerns, operational impact and equal consideration of social, environmental and economic issues (Crane et al. 2008b) to the use of social or environmental activities to support strategic goals. Combine this with practicing CSR using tools that have been co-opted from other business activities, and the result is that CSR, in how it is practised by MNCs, has become more ‘business as usual’ instead of a mechanism for motivating fundamental changes in how business operates. Therefore, after an initial challenge from stakeholders, MNCs were able to control how CSR would be conducted within their organizations and used tools and other structures emanating from the market logic to do so.

The Future of CSR?

The research clearly shows an institution of CSR in MNCs that is influenced not only by institutional pressures (e.g. Boxenbaum 2006; Campbell 2007; Jackson and Apostolakou 2010) but by a significant degree of agency within and between MNCs. Although recognizing the importance of their impacts on stakeholders in their justifications and other discursive tools, the MNCs focused their activity on particular CSR practices that were strategically aligned with core operating strategy. They thus symbolically reflected (Jermier et al. 2006) the broader CSR logic whilst redefining it internally to be consistent with the market logic. In so doing, they ensured that whilst stakeholders were consulted, they were largely kept out of the decision making processes on specific activities. In this way, the incumbents were able to maintain control over the emerging field of CSR such that it did not impinge in any meaningful way on their pursuit of traditional business imperatives.

Therefore, whilst much of what we have come to understand as CSR is thought to have arisen through stakeholder pressures (Hoffman 2001; Phillips et al. 2003; Stevens et al. 2004), the form of CSR as currently practised by UK MNCs is as much the result of their own activities and agendas. This is not to say stakeholders have no influence, but to suggest that their ability to shape CSR within MNCs may be less important than how MNCs use the general concept of CSR in a strategic way to further business interests.

As this shift towards ‘strategic CSR’ in MNCs continues to be mimicked and translated by other companies, there is a likelihood that it will come to mean marketing the social/environmental, rather than strategies for aligning the social, environmental and the economic. Whilst we see no problem in CSR strategies serving broader business purposes, the fear is current practice will continue to undermine the core logic of CSR. Ironically perhaps, this recalls Friedman’s (1970) observation that whilst business investments in the community may generate business advantages, to describe such self-interested activities as socially responsible is mere ‘window-dressing’. We are not suggesting that the business case is necessarily anti-social. Our findings however suggest a danger that even the institutionalization of CSR can serve the precise problem that CSR was intended to address: the pursuit of economic goals at the expense of social and environmental responsibility.

Conclusion

This research contributes to both the mainstream and critical CSR literatures. First, by bringing together existing contributions to demonstrate an institution of CSR, and providing empirical evidence of a CSR institution within MNCs, it provides solid evidence of the existence of an institution of CSR, and how it is practised by some of its most influential players. It therefore adds to our understanding of CSR within the mainstream literature by describing one form of the institution within a particular institutional context (e.g. Boxenbaum 2006; Doh et al. 2010; Jackson and Apostolakou 2010). Second, an investigation of the specific practices of MNCs relative to CSR has identified a subtle but significant shift in the types of activities in which MNCs engage. By shifting their focus to specific CSR activities that have strong strategic importance, these companies place social and environmental considerations as subservient to economic concerns. By so doing, they undermine one of the core foundations of CSR that places all three considerations on equal footing. It therefore contributes to the growing body of critical CSR literature (e.g. Banerjee 2007; Bondy 2008; Matten and Moon 2008) that challenges mainstream assumptions about CSR within organizations. In particular, it looks at specific CSR practices to critically evaluate the implications of this activity for the field of CSR (Banerjee 2007; Devinney 2009). It therefore suggests that current practice of CSR in MNCs is increasingly turning it into a ‘business as usual’ practice instead of forming a foundational challenge to the current relationship between business and society (Doane 2005).

Notes

Externalities are costs that are borne by groups who are not party to a transaction and exist where markets fail to reflect the full costs to society of particular acts of production or consumption. For instance, when I fly, people other than the airline staff and me face the consequences of the pollution of that flight.

The FAME database provides detailed financial and business intelligence information on over seven million UK and Irish businesses with up to 10 years of history. This allowed us to identify the largest companies according to sales revenue in the UK.

Dimensionalization refers to taking a higher-order theme and placing it on a continuum or other similar analytic device to define the range of ‘dimensions’ that encompass the theme. This allows for detailed analysis of a specific theme, particularly where participants discuss the same theme in different ways.

CSR competitors were generally considered to be either good/service competitors, or were other MNCs who were seen to be leaders in preferred CSR aspects, such as community engagement strategies, code development or report writing.

In the case of consulting companies, the interviews consisted of discussing what the consultancy itself does with regard to CSR and any experience it may have with other MNCs with which it has worked.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multi-level theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 836–863.

Arenas, D., Lozano, J., & Albareda, L. (2009). The role of NGOs in CSR: Mutual perceptions among stakeholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 88, 175–197.

Bacharach, S., Bamberger, P., & Sonnenstuhl, W. (1996). The organizational transformation process: The micropolitics of dissonance reduction and the alignment of logics of action. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 477–506.

Baker, M. (2002). Research methods. The Marketing Review, 3, 167–193.

Banerjee, S. B. (2007). Corporate social responsibility: The good, the bad and the ugly. Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

Beckert, J. (1999). Agency, entrepreneurs, and institutional change. The role of strategic choice and institutionalized practices in organizations. Organization Studies, 20(5), 777–799.

Beliveau, B., Cottrill, M., & O’Neill, H. (1994). Predicting corporate social responsiveness: A model drawn from three perspectives. Journal of Business Ethics, 13(9), 731–738.

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1967). The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge. London: Penguin Press.

Bies, R., Bartunek, J., Fort, T., & Zald, M. (2007). Corporations as social change agents: Individual, interpersonal, institutional and environmental dynamics. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 788–793.

Blowfield, M. (2005). Corporate social responsibility: The failing discipline and why it matters for international relations. International Relations, 19(2), 173–191.

Blowfield, M., & Frynas, J. G. (2005). Setting new agendas: Critical perspectives on corporate social responsibility in the developing world. International Affairs, 81(3), 499–513.

Bondy, K. (2008). The paradox of power in CSR: A case study on implementation. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(2), 307–323.

Bondy, K., Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008). Multinational corporation codes of conduct: Governance tools for corporate social responsibility? Corporate Governance: An International Review, 16(4), 294–311.

Boxenbaum, E. (2006). Corporate social responsibility as institutional hybrids. Journal of Business Strategies, 23(1), 45–64.

Brammer, S., & Millington, A. (2003). The evolution of corporate charitable contributions in the UK between 1989 and 1999: Industry structure and stakeholder influences. Business Ethics: A European Review, 12(3), 216–228.

Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1979). Sociological paradigms and organisational analysis. England: Gower Publishing.

Campbell, J. (2007). Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 946–967.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three dimensional model of corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 4, 497–505.

Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Consolandi, C., Jaiswal-Dale, A., Poggiani, E., & Vercelli, A. (2009). Global standards and ethical stock indexes: The case of the Dow Jones Sustainability Stoxx index. Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 185–197.

Coupland, C., & Brown, A. D. (2004). Constructing organizational identities on the web: A case study of Royal Dutch/Shell. Journal of Management Studies, 41(8), 1325–1347.

Cragg, W., & Greenbaum, A. (2002). Reasoning about responsibilities: Mining company managers on what stakeholders are owed. Journal of Business Ethics, 39, 319–335.

Cramer, J. (2005). Experiences with structuring corporate social responsibility in Dutch industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 13, 583–592.

Crane, A., Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2008a). Corporations and citizenship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crane, A., Matten, D., & Spence, L. (2008b). Corporate social responsibility: in a global context. In A. Crane, D. Matten, & L. Spence (Eds.), Corporate social responsibility: Readings and cases in a global context (pp. 3–20). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Creed, D., Scully, M., & Austin, J. (2002). Clothes make the person? The tailoring of legitimating accounts and the social construction of identity. Organization Science, 13(5), 475–496.

Curry, T., Ansolabehere, S., & Herzog, H. (2007). A survey of public attitudes towards climate change and climate change mitigation technologies in the United States: Analysis of 2006 results.

Czarniawska, B., & Joerges, B. (1996). Travel of ideas. In B. Czarniawska & G. Sevon (Eds.), Translating the organizational change. New York: Walter De Gruyter.

Davenport, K. (2000). Corporate citizenship: A stakeholder approach for defining corporate social performance and identifying measures for assessing it. Business & Society, 39(2), 210–219.

Davies, I. A. (2009). Alliances and networks: Creating success in the UK fair trade market. Journal of Business Ethics, 86, 109–126.

Davis, K. (1960). Can business afford to ignore corporate social responsibilities? California Management Review, 2, 70–76.

Den Hond, F., & De Bakker, F. G. A. (2007). Ideologically motivated activism: How activist groups influence corporate social change activities. Academy of Management Review, 32, 901–924.

Detomasi, D. A. (2008). The political roots of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 807–819.

Devinney, T. (2009). Is the socially responsible corporation a myth? The good, the bad, and the ugly of Corporate Social Responsibility. Academy of Management Perspectives, 23(2), 44–56.

Dijksterhuis, M., Van den Bosch, F., & Volberda, H. (1999). Where do new organizational forms come from? Management logics as a source of coevolution. Organization Science, 10(5), 569–582.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 147–160.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. (1991). Introduction. In W. Powell & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Doane, D. (2005). The myth of CSR: The problem with assuming that companies can do well while also doing good is that markets don’t really work that way. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 3(fall), 22–29.

Doh, J. P., & Guay, T. R. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1), 47–73.

Doh, J., Howton, S., Howton, S., & Siegal, D. (2010). Does the market respond to an endorsement of social responsibility? The role of institutions, information and legitimacy. Journal of Management, 36(6), 1461–1485.

Donaldson, T., & Dunfee, T. W. (1994). Toward a unified conception of business ethics: Integrative social contracts theory. Academy of Management Review, 19, 252–284.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91.

Dunning, J. (1998). Reappraising the eclectic paradigm in an age of alliance capitalism. In M. Colombo (Ed.), The changing boundaries of the firm (pp. 29–59). London: Routledge.

ECCR. (2006). News release: Responsible investors back Shell shareholder resolution.

Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Oxford: Capstone Publishing Ltd.

Elkington, J. (1998). The ‘triple bottom line’ for twenty-first-century business. In J. V. Mitchell (Ed.), Companies in a world of conflict: NGOs, sanctions and corporate responsibility (pp. 32–69). London: The Royal Institute of International Affairs/Earthscan.

European Commission. (2008). Europeans’ attitudes towards climate change.

Fiss, P., Kennedy, M., & Davis, G. (2011). How golden parachutes unfolded: Diffusion and variation of a controversial practice. Organization Science, Articles in Advance, 1–23.

Fiss, P., & Zajac, E. (2004). The diffusion of ideas over contested terrain: The (non)adoption of a shareholder value orientation among German firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 501–534.

Fligstein, N. (2001). Social skill and the theory of fields. Sociological Theory, 19(2), 105–125.

Fransen, L. W., & Kolk, A. (2007). Global rule-setting for business: A critical analysis of multi-stakeholder standards. Organization, 14(5), 667–684.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management. A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Friedland, R., & Alford, R. (1991). Bringing society back in: Symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions. In W. Powell & P. DiMaggio (Eds.), The new institutionalism in organizational analysis (pp. 232–263). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.

Garriga, E., & Melé, D. (2004). Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. Journal of Business Ethics, 53(1–2), 51–71.

Gerson, K., & Horowitz, R. (2002). Observation and interviewing: Options and choices in qualitative research. In T. May (Ed.), Qualitative research in action. London: Sage.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. New York: Aldine.

Global Reporting Initiative. (1999). Sustainability reporting guidelines: Exposure draft for public comment and pilot-testing. In M. Bennett, P. James, & L. Klinkers (Eds.), Sustainable measures: Evaluation and reporting of environmental and social performance. Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf Publishing.

Glynn, M. A., & Lounsbury, M. (2005). From the critics’ corner: Logic blending, discursive change and authenticity in a cultural production system. Journal of Management Studies, 42(5), 1031–1055.

Gond, J.-P., Kang, N., & Moon, J. (2011). The government of self-regulation: On the comparative dynamics of corporate social responsibility. Economy and Society (forthcoming).

Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510.

Gray, R. (2001). Thirty years of social accounting, reporting and auditing: What (if anything) have we learnt? Business Ethics: A European Review, 10(1), 9–15.

Hensmans, M. (2003). Social movement organizations: A metaphone for strategic actors in institutional fields. Organization Studies, 24(3), 355–381.

Hoffman, A. J. (2001). From heresy to Dogma: An institutional history of corporate environmentalism. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Holstein, J., & Gubrium, J. (1995). The active interview. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Husted, B. W. (2003). Governance choices for corporate social responsibility: To contribute, collaborate or internalize? Long Range Planning, 36(5), 481–498.

Husted, B., & Allen, D. (2007). Strategic corporate social responsibility and value creation among large firms: Lessons from the Spanish experience. Long Range Planning, 40, 594–610.

Idemudia, U. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and developing countries: Moving the critical CSR research agenda in Africa forward. Progress in Development Studies, 11(1), 1–18.

Jackson, G., & Apostolakou, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility in Western Europe: An institutional mirror or substitute. Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 371–394.

Jermier, J. M., Forbes, L. C., Benn, S., & Orsato, R. J. (2006). The new corporate environmentalism and green politics. In S. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. Lawrence, & W. R. Nord (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organization studies (pp. 618–650). London: Sage.

Johnson, P. (2006). Whence democracy? A review and critique of the conceptual dimensions and implications of the business case for organizational democracy. Organization, 13(2), 245–274.

Kaufman, A., Tiantubtim, E., Pussayapibul, N., & Davids, P. (2004). Implementing voluntary labour standards and codes of conduct in the Thai garment industry. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 13, 91–99.

Keats, D. (2000). Interviewing: A practical guide for students and professionals. Buckingham: Open University Press.

King, B., & Pearce, N. (2010). The contentiousness of markets: Politics, social movements and institutional change in markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 249–267.

Knight, J. (1992). Institutions and social conflict. Cambridge, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Kurucz, E., Colbert, B., & Wheeler, D. (2008). The business case for corporate social responsibility. In A. Crane, A. McWilliams, D. Matten, J. Moon, & D. Siegal (Eds.), The oxford handbook of corporate social responsibility (pp. 83–112). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691–710.

Langlois, C. C., & Schlegelmilch, B. B. (1990). Do corporate codes of ethics reflect national character? Evidence from Europe and the United States. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(4), 519–539.

Laplume, A., Sonpar, K., & Litz, R. (2008). Stakeholder theory: Reviewing a theory that moves us. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1152–1189.

Levy, D. L. (2008). Political contestation in global production networks. Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 943–963.

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, Ca: Sage.

Linneroth-Bayer, J., Löfstedt, R., & Sjöstedt, G. (2001). Transboundary risk management. London: Earthscan.

Lounsbury, M. (2001). Institutional sources of practice variation: Staffing college and university recycling programs. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(1), 29–56.

Lounsbury, M. (2002). Institutional transformation and status mobility: The professionalization of the field of finance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 255–266.

Lounsbury, M., & Crumley, E. (2007). New practice creation: An institutional perspective on innovation. Organization Studies, 28(7), 993–1012.

Macalister, T. (2010). Tony Hayward’s parting shot: ‘I’m too busy to attend Senate hearing.