Abstract

Current International Accountability Standards for sustainability reporting, such as The United Nations Global Compact and the Global Reporting Initiative are subject to criticism from two sides, researchers and practitioners. Through interviews with key persons from audit firms and a systematic literature review, we identify major deficiencies in current corporate sustainability reporting practices. Based on these findings, we derive five propositions which address the need for future improvements, i.e. we propose that a dynamic standard for corporate sustainability reporting must capture a firm’s longitudinal learning and development of intra- and inter-organizational sustainability capabilities by integrating them as leading indicators. We conclude the article with an outlook on future paths for an improved sustainability reporting framework focusing on intra- and inter-organizational capabilities and best practices which are proposed to have an impact on sustainability performance along the entire supply chain.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Sustainability reporting

- Best practices

- Sustainability capabilities

- Supply chain

- International Accountability Standards

1 Introduction

Corporate efforts in assuring sustainability activities have increased continuously during the last decades. In 2013 more than 90 % of the top 250 organizations listed on the Fortune Global 500 ranking used a sustainability report to display their sustainability undertakings (KPMG 2013). At the same time, the field of sustainability reporting has undergone a significant consolidation in which some major International Accountability Standards (IAS) have emerged. Among these reporting frameworks are the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC), the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the AccountAbility 1000 (AA1000), as well as the Social Accountability 8000 (SA8000).

Nonetheless, the trend towards increasing reporting practices has not implicitly caused more excellence in every aspect. Despite the positive effect of overall and particularly firms’ awareness of the need to strive for sustainability and to assure these activities, there is still a call for improvements of IAS from scholarly research and practice. Particularly two major areas for improvement can be identified.

On the one hand a wider integration of activities and factors which are lying beyond the direct impact of the corporation is needed. In its 2013 annual review, the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) pointed to this improvement gap and called organizations to provide evidence to show they are engaging with suppliers and customers to address material risks and opportunities identified along the supply chain (WBCSD 2013). This is in line with the fourth generation of the GRI guidelines (GRI4) for sustainability reporting which also emphasize the requirement to focus on supply chain aspects and presents an extended set of indicators for supply chain reporting compared to previous GRI guidelines. Since GRI4 has only recently been issued, corporations’ adoption is still very low, but these new reporting structures are bound to influence corporate reporting practice and potentially also corporations’ management of their sustainability practice in the future.

On the other hand a move away from lagging indicators towards a more capability-based view referring to leading indicators is often called for (e.g. Peloza 2009). Although achieving corporate sustainability is often a time intensive learning process (Kaptein and Wempe 1998) that requires organizational capabilities, this learning perspective is mostly neglected when it comes to sustainability performance and the reporting of its indicators. Consequently, corporations engaged in sustainability reporting primarily collect and disclose data for lagging indicators. The “work related injury rate” from the GRI framework for example shows only factual past performance and does not inform corporate management and stakeholders on the actual capabilities in this regard. On the contrary, practices like a written company policy on labor and risk and impact assessments in the area of labor from the UNGC framework can be perceived as leading indicators, potentially representing capabilities which are essential for corporate decision-making and the advancement of sustainability performance. Furthermore, focusing on leading indicators and capabilities enhances transparency within reporting processes and stakeholders will get an improved understanding of the sources for sustainability performance. Thus, in contrast to less successful attempts to design IAS analogous to financial reporting (Etzion and Ferraro 2010) relying mostly on lagging indicators, this articleFootnote 1 follows the direction of proposing a learning and capability focused framework for sustainability reporting building on best practices for sustainability performance.

By actively embracing an inter-organizational supply chain perspective within the context of sustainability reporting practices, we not only provide a remedy for the WBCSD gap mentioned above but also pave the way for a reporting framework that accounts for environmental and social performance along the entire supply chain. From this perspective, entangling supply chain management with sustainability reporting allows for a new interpretation of both. Sustainability reporting should be considered as a management instrument of sustainable supply chain management and no longer as a mere reporting of past performance.

The paper is structured as follows. In the next section, we briefly describe the applied research process, followed by our findings which result in the presentation of five propositions. Simultaneously, we focus on identifying best practices for sustainability reporting. The final sections provide a future outlook on the new framework and conclude this research note.

2 Research Process

In order to leverage the purposes described above, a research process with two major steps was applied. The first part of our research focuses on interviews with key informants from auditing firms, while the second part of our study provides a systematic literature review of supply chain related best practices with a positive effect on sustainability performance.

In order to gain a broader insight from corporate practice regarding the identification of deficiencies in current reporting practices, we chose to interview senior consultants specialized in sustainability reporting from three of the “Big Four” auditing firms. This choice was particularly motivated by two reasons. First, senior consultants in the area of sustainability assurance and auditing are by definition well-informed on current developments in the area of sustainability reporting and possess an extensive expertise and experience in that area. Second, these key informants advise their clients in IAS implementation processes and their audit firms are consulted on or directly involved in the development of both multi-stakeholder standards and industry-specific standards.

The three semi-structured interviews followed the same standardized approach. An interview guide was developed with a series of standard questions based on relevant topics, but the answers in one interview also led to additional questions in the following interview and the interviewers had the freedom to pose ad hoc questions during the interviews.

The key findings framed our approach to focus on sustainability best practices and served as input to the further research process, which was undertaken as a systematic literature review of scholarly articles published in the years 2005–2015. The sampling process was based on a keyword search in the databases ScienceDirect and EBSCO searching for articles that included combinations of the keywords such as “drivers”, “antecedents”, “practices”, or “factors” and variations and synonyms of “supply chain performance”. From the initial set of relevant articles we removed those published in journals with a rating of below 0.3 according to the “Handelsblatt Ranking BWL 2012”. We then screened the remaining papers and excluded articles of which the titles did not fit our research purposes. Subsequently, we eliminated articles with abstract that did not match our goals. The final set consisted of 38 scientific articles which were analyzed in-depth by two researchers independently with the goal of identifying potential supply chain related best practices. The identified best practices were discussed, clustered, and aggregated.

3 Findings

In this section we describe the results of our research process in detail. First, we provide a summary and overview of findings from the key informant interviews. These new insights are then linked to current IAS and reporting literature. A set of five propositions addresses the identified deficiencies and paves the road for a revised and improved framework for corporate sustainability reporting according to IAS, thereby integrating a broader supply chain context. As we particularly emphasize the capability-oriented logic as the most interesting and important characteristic of the proposed framework, which influences all other design issues, we extract best practices for sustainability performance from the academic literature in the second part of our result section.

3.1 Insights from Auditing Firms on IAS and Clients’ Adoption

In the following we outline the results of interviews with key sustainability professionals of three of the “Big Four” auditing firms. Table 1 illustrates the interviewees’ quotes for each of the topics raised during the interviews. In the subsequent part these different issues are analyzed in order to provide a basis for developing propositions towards a framework.

As a first perspective, we address the process of IAS adoption, which includes the view on how the interviewees and their clients perceive and use these standards. All sustainability audit professionals (SAPs) stated that most of their major clients use a version (3.0, 3.2 or 4) of the GRI guidelines which they all assess to be the most adopted IAS among their clients. Two of the SAPs stated that the UNGC is also widely followed among their clients, whereas SAP2 indicated a lower adoption rate for the UNGC.

Although the IAS adoption rate already indicates the extent to which corporate sustainability reporting is present in practice throughout different industries, determination of the quality of the reporting practice requires supplementary information with regard to how corporations perceive, prioritize, and apply IAS. SAP1 illustrated this aspect by stating that reporting according to the UNGC is a “side product” to the GRI reporting, disregarding the UNGC Advanced Level as generally not being the key focus of reporting for organizations. Even more, SAP3 suggested that the UNGC Advanced Level suits only a few publicly listed large companies, implying that most UNGC adopters rather report on the principle-based Active Level.

SAP2 elaborated in more detail on the complexity and intangibility of the UNGC as reasons for the lower adoption rate among his clients. In general, the SAPs consider the GRI as more tangible but at the same time as very comprehensive, resource demanding, and not unproblematic in terms of comparability and interpretation. This holds in particular for the GRI A+ application level, which is the highest reporting level in the GRI guidelines and the main target level of many major clients in SAP1’s audit firm. On the contrary, a smaller group of clients consider it less important to cover all indicators required to receive the A+ application level. Rather, they focus on indicators which are usually more material for stakeholders, according to SAP1. This trend towards materiality is also embedded in GRI 4 which incorporates a definition of materiality central to the framework for integrated reporting developed by the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC).

SAP1 recognized GRI 4 as a move away from the traditional ABC levels and suggested that an increased materiality focus might lead to more accurate and differentiated reporting based on actual stakeholder interests. SAP1 further predicted that supply chain sustainability would thus increasingly become a highly important topic that organizations will need to report on (Table 1).

During the interview with SAP1 the interviewee informed us that the GRI 4 aims to better address upstream supply chain tiers and that they currently contain some preparatory steps towards higher tiers. Although a supply chain perspective is not completely absent in previous GRI guidelines and despite the fact that supply chain related indicators can also be found in the UNGC Advanced Level, the progress towards greater specificity for more upstream tiers in GRI 4 can be considered a significant advancement which can provide stakeholders with new informative insights. GRI 4 thereby addresses an information gap as mentioned by SAP1. According to this interviewee, supply chain reporting can be framed as reporting of company or product performance emerging between several business partners. The interviewee further indicates that this kind of reporting will rarely be conducted by using multi-stakeholder standards such as the GRI or the UNGC. It is rather a matter of assessing suppliers’ sustainability performance based on a set of criteria defined by customers, according to SAP1.

However, reporting to company-specific criteria is highly challenging for suppliers that usually supply multiple focal companies. For this reason, SAP1’s audit firm works towards more industry-wide applicability of reporting practices. SAP2’s audit firm represents mainly clients in the mid-market that are often suppliers to focal companies. She stated that her clients generally adapt the industry’s specific standards because stakeholders often require it. Consequently, identifying standards relevant for clients and determining their importance for stakeholders remains a big challenge for SAP2’s firm. As a remedy, SAP2 said this problem could be addressed with a standard that is specific for a particular industry and at the same time compatible with the most relevant of other industry-specific standards. However, such an initiative will still be challenged by the fact that most of the clients only acknowledge a need to address tier 1 of their supply chain and do not recognize their responsibility for actions including more distinct suppliers. With regard to potential benefits of integrating supply chain perspectives into reporting, SAP3 commented that although guidelines, codes of conduct, and other monitoring and governance mechanisms might reduce reputation and quality risks, these issues remain difficult to measure and value for organizations. More directly, SAP1 questioned whether measuring supply chain indicators is relevant and feasible at all, adding that if this were the case, the measurement would need to encompass a longer time horizon in order to capture long-term effects.

3.2 Towards an Improved Framework for Sustainability Reporting

The interviews indicate that although both IAS, GRI and UNGC, show high adoption rates among firms, GRI is clearly the IAS priority in corporate reporting practice. Yet, the actual degree of corporate implementation of IAS seems to vary significantly. Despite the positive aspect of their diffusion, there is still a need for an integration of an extended supply chain perspective across IAS such as the GRI and UNGC. Consequently, scholars have stressed the need “to look outside an organization’s boundaries” when it comes to sustainability performance (Meehan and Bryde 2011, p. 95). Moreover, stakeholders have developed a distinctive awareness for these issues, hence nowadays firms, such as Nike, Apple and BP are often held liable for their supply chain partners when it comes to environmental and social incidents (Hartmann and Moeller 2014). Partly because of these developments, companies like Microsoft have started to actively embrace external partners in their supply chains by requiring annual sustainability reports. Thus, we suggest:

P1: A dynamic standard for corporate sustainability reporting must require accounts for sustainability issues both within the boundaries of the corporation and in the corporate supply chain.

Moreover, an increasing trend towards defining materiality within sustainability reporting practices was identified in conformance with the debates in the academic literature. Although materiality is a fundamental concept stemming from modern accounting (Messier et al. 2005), due to the increased call from practice and scholars, materiality has diffused into the field of sustainability, where it continuously gains relevance. Nonetheless, many scholars point out a lack of materiality considerations within sustainability reporting and a high potential to develop the field further in this regard (e.g. Kanzer 2010). Although the materiality concept is well-known and called for within IAS and the reporting literature, we adopt this critical aspect and hence propose:

P2: A dynamic standard for corporate sustainability reporting must integrate the concept of materiality, accounting for whether the reported information concerns core business activities within the supply chain, that are material to the society, the corporation, or both, in an integrative manner.

Labeling the UNGC as complex and not tangible is also reflected in the IAS-related literature, where some of the criticism focuses on the lack of precision (Bigge 2004; Nolan 2005) in the description of UNGC principles and their generality (Deva 2006). These issues make the UNGC hard to understand and apply for organizations. The GRI is perceived as more tangible, but also comprehensive, resource demanding and—despite a large number of quantitative indicators—at least to some degree incomparable. Particularly this last point of critique is also present in scholarly literature (Dingwerth and Eichinger 2010; Levy et al. 2010). The overall lack of comparability weakens the UNGC and GRI as potential frameworks for measuring and reporting sustainability performance. This is especially problematic as the concept of comparability is central for standards in general and for IAS in particular. Part of the problem (and the solution) is touched upon in the interviews, which question the value of quantitative indicators if information about the factors influencing the annual decrease or increase is not reported in a comparable and uniform way. For instance, the increase or decrease of a company’s energy consumption rate is influenced by external factors such as weather or demand and not only by its sustainability activities. Hence, certain aspects within sustainability reporting and measurement of sustainable performance require a differentiated view. Yet, these important issues are only scarcely discussed topics in the IAS literature, but have been known and debated in the accounting literature for decades under the concepts of “leading and lagging indicators”.

Epstein and Roy (2001) describe the common understanding of leading indicators as input or process indicators that connect more closely to operations. Hence, in order to link corporate activities with corporate strategic objectives, sustainability performance measures “must include leading indicators that give insight into the organization’s ability to improve its competitive position in the future and are predictors of future performance” (Epstein and Roy 2001, p. 600). This idea is in line with Peloza (2009, p. 1522) who identifies leading and lagging indicators as mediating metrics which are “those that capture the ‘mediating variable’ that generates business value” as opposed to intermediate or end state outcome metrics. Both leading and lagging indicators can be of a quantitative nature, but the important point is that considering a leading indicator as an organizational ability, means that it is most often a composite of a number of complementary corporate practices: best practices for sustainability performance.

Paradoxically, in 2010 the UNGC introduced the Differentiation Programme with an Advanced Level for reporting, based on corporate adherence to 100+ best practices, which allows for benchmarking and comparability on e.g. supply chain implementation of the UNGC principles. However, the adoption rate of this Advanced Level is relatively low, as it comprises a number of conceptual weaknesses. These weaknesses make the Advanced Level potentially subject to criticism, although its existence has been relatively undetected in the IAS literature which perceives the UNGC still as a solely principle-based IAS. Nevertheless, it is worth noticing that the best practices described in this framework do not differ much across the UNGC issues: Labor, Human Rights, Environment, and Anti-Corruption. This feature makes it interesting per se to have a closer look, particularly against the background of a need for a cross-industry standard as identified in the interviews. In other words, while some lagging indicators for sustainability performance will be more material in some industries than others, best practices as leading indicators will differ less across industries and be less subject to individual firms’ or industries’ materiality concerns. Taking buyer-supplier collaboration as a best practice in order to increase sustainability performance along the supply chain, the following example illustrates the advantage of capability approaches: The general characteristics of a focal company’s collaboration with its suppliers on a certain environmental issue like for instance the reduction of CO2-emissions will not differ much from the general characteristics of another company’s collaboration with a focus on labor issues such as working hours. However, the mere numbers of CO2-emissions and the amount of working hours of employees are in this case lagging indicators measured in very different ways. Traditional reporting practices just publish these numbers and leave stakeholders alone in interpreting it. This holds especially in situations where companies from different industries report on the same lagging indicators. It is self-evident that an IT provider will have lower numbers of CO2-emissions than a coal power station. But where is the line between sustainable or unsustainable performance drawn then? This leads us to propose that a standard for supply chains should better be based on best practices as factors that describe organizations’ capabilities for sustainability. Such a standard could overarch different industries and supplement industry standards, which use specific quantitative measures for lagging indicators. Thus, we postulate:

P3: A dynamic standard for corporate sustainability reporting must allow for industry-specific indicators as well as cross-industry applicability.

P4: A dynamic standard for corporate sustainability reporting must capture a firm’s longitudinal learning and development of intra- and inter-organizational sustainability capabilities by integrating them as leading indicators.

In the following we focus on this last proposition as the capability approach, which is the most important aspect and the most promising compared to deficiencies of current IAS.

3.3 Best Practices for Improving Sustainability Performance

Building on a systematic account of scholarly literature in the area of sustainable supply chain management, we are able to identify and aggregate several practices driving sustainability performance along the supply chain. Following Beske et al. (2014) who find best practices to be a resemblance of a firm’s capabilities, we consider the extracted practices to provide a first step towards an improved sustainability reporting framework which focuses on firms’ intra- and inter-organizational capabilities in enabling sustainability performance (Table 2).

In order to improve their sustainability performance, organizations must be aware of their sustainability impact along the supply chain (Beske and Seuring 2014). This can for example be done by measures such as integrated carbon management (e.g. Gopalakrishnan et al. 2012) or a general internal performance measurement system (e.g. Zhu et al. 2013). Furthermore, stakeholder management and regular consultations with external actors have been found to drive sustainability performance (e.g. Pagell and Wu 2009; Wu et al. 2014). Related to this, Beske et al. (2014) and Carter and Rogers (2008) emphasize that a focus should lie on proactive communication about sustainability related issues. These communication practices, internal as well as external, are considered to be a key factor driving sustainability performance (Beske et al. 2014).

Several authors highlight the ambivalence of both risks and opportunities associated with social and environmental issues along the supply chain (e.g. Foerstl et al. 2010; Hofmann et al. 2014); Leppelt et al. 2013. Hence, companies should carefully monitor and manage these risks and look for opportunities that emerge for example together with new environmental developments (e.g. Klassen and Vereecke 2012).

As organizational sustainability initially requires resources and sometimes investments, and needs to be spread throughout the entire organization, successful practices should rely on top management involvement (e.g. Seuring and Müller 2008; Zhu et al. 2008; Pagell and Wu 2009), an adapted organizational culture (e.g. Carter and Rogers 2008; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2012) and extensive internal environmental reporting (e.g. Zhu et al. 2013). Internally, trainings enhance worker sustainability competences and raise awareness (e.g. Zhu et al. 2007, 2013). Externally, open communication, transparency and supplier development with sustained long term relationships are considered to be essential (e.g. Seuring and Müller 2008; Beske and Seuring 2014).

Ensuring sustainability not only intraorganizationally but along the supply chain rests on organizations’ capabilities in buying goods and services that are already sustainable as in practices like green purchasing (e.g. Zhu et al. 2007, 2013). As purchasing departments account for the entire input part of a company, improving the overall sustainability performance starts with carefully selecting and consistently monitoring and evaluating suppliers (e.g. Klassen and Vereecke 2012). For these purposes sustainability criteria need to be clearly defined and included in supplier selection processes (Gold et al. 2010; Gopalakrishnan et al. 2012; Beske et al. 2014). Additionally, in order to manage these processes effectively, companies need to set clear goals and targets (e.g. Gopalakrishnan et al. 2012; Large and Gimenez Thomsen 2011) and communicate those across the supply chain, for example via policies and a (supplier) code of conduct (e.g. Jiang 2009; Schleper and Busse 2013). Moreover, besides these governance and control-based processes, close collaboration and information sharing with customers and suppliers can foster environmental and social initiatives as well as innovations (e.g. Seuring and Müller 2008; Zhu et al. 2008; Klassen and Vereecke 2012; Beske and Seuring 2014).

In general, scholars stress the importance and opportunities of innovation (Klassen and Vereecke 2012). Establishing a sustainable supply chain can lead to new product developments and other innovations (Beske and Seuring 2014) and increased adaption of products and processes (Gavronski et al. 2012), for instance in the context of eco-design paradigms (e.g. Zhu et al. 2008; Hoejmose et al. 2012).

In conclusion, there are many practices that foster the establishment of a sustainable supply chain. The degree to which an organization internalizes and implements these practices hints towards their true sustainability capabilities and hence their potential in performing sustainably. Thus, in addition to P4 we add:

P4*: A dynamic standard for corporate sustainability reporting must capture a firm’s intra- and inter-organizational sustainability capabilities by incorporating a saturated set of best practices which have been empirically found to have a positive impact on sustainability performance.

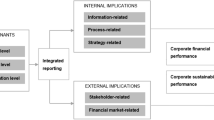

4 A Path for Future Improvement: Towards a New Framework

So far we presented five propositions as requirements for corporate sustainability reporting. In this section, we briefly describe how these propositions might be included in a new framework. The identification of a set of intra- and inter-organizational best practices that have empirically proven to be relevant in the enhancement of sustainability performance is an important first step, yet needs to be linked to theory.

An adequate candidate for one such theory could be the notion of absorptive capacity (ACAP) which concerns a firm’s ability to acquire, assimilate, transform, and apply external knowledge (Cohen and Levinthal 1990; Zahra and George 2002).

In times of dynamic markets and highly uncertain environments, knowledge is the dominant source for competitive advantage (Jansen et al. 2005) as learning mechanisms enable organizations to “create, extend or modify its resource base” (Helfat et al. 2007, p. 4) thereby equipping them with new routines to prepare for future uncertainties. Hence, a high ACAP can strongly influence the overall performance of firms and their long term survival as it describes a firm’s potential not only to analyze changes and turbulences in markets in which they operate but also to simultaneously process, internalize and use the newly acquired knowledge (Cohen and Levinthal 1990). Yet, particularly in the context of sustainability, there is still a lack of ACAP considerations within scholarly research, although it is a very complex topic and prone to a high uncertainty environment.

Applying the ACAP concept as a theoretical base offers a novel focus for exploring corporations’ implementation of IAS. In particular, this framework provides several aspects, which are requested in the above stated propositions. In the following, two of these aspects are characterized:

-

1.

Through its strong orientation towards the absorption of external sources of knowledge, ACAP emphasizes supply chain integration as a factor for potentially enabling sustainable competitive advantage. Raising this awareness within companies might also foster a closer collaboration between supply chain partners, thereby achieving certain specific goals like for instance boundary-spanning CO2-emission reductions (Ramanathan et al. 2014).

-

2.

Focusing on ACAP allows reporting firms to invest in building internal capabilities in the area of sustainability. Through these capabilities highly dynamic and uncertain environments, present when dealing with sustainability issues, become more manageable for companies. For instance, Lichtenthaler (2009) points out that learning processes linked to ACAP guide organizations’ innovative potentials; particularly if they align their internal combinative capabilities—systematization, coordination, and socialization of knowledge—with the absorbed new information.

To further utilize the ACAP concept we suggest structuring the best practices vertically along the four ACAP dimensions to include a progressive organizational capabilities and learning perspective. Yet, as extracted from the key informant interviews, the actual implementation of best practices among companies differs. Hence, an improved reporting guideline needs to allow for differentiation in this regard as this also enables measurability of sustainable performance and comparability across industries. Implementation levels that account for different degrees of effort in best practices allow for weighing the actual performance of organizations.

5 Conclusion

The emergence of various IAS following different approaches reflects the importance of sustainability reporting. However, current IAS suffer from several shortcomings which prevent communicating a firm’s real and holistic value and which often leave reporting disconnected from an organization’s actual operations. In this research note, we uncovered these deficiencies and provided five propositions which pave the road for an innovative and dynamic framework for corporate sustainability reporting.

A new standard should incorporate a firm’s entire supply chain and ensure reporting outside the firm-boundaries, thereby meeting environmental and social requirements. We follow an ongoing debate about lagging and leading sustainability performance indicators by proposing an approach that focuses on an organization’s intra- and inter-organizational capabilities. These capabilities can be best built and expressed by best practices that improve an organization’s sustainability performance along the entire supply chain. Since current standards further lack an objective scale to value the degree of capability implementation achieved to make reports more accurate and enable comparability, we outline the need to develop mechanisms that allow the new reporting standard to weigh and differentiate organizations’ efforts across industries. One theoretical basis for these features could be provided by utilizing the ACAP concept to structure the best practices we extracted from scholarly literature. However, much remains to be done to reduce complexity in the field and to ensure effective and efficient reporting for all stakeholders along the supply chain.

Notes

- 1.

This article is a scientific excerpt from an ongoing research project. We gratefully acknowledge that this project is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research, grant no. 01IC10L14A.

References

Beske P, Land A, Seuring S (2014) Sustainable supply chain management practices and dynamic capabilities in the food industry: a critical analysis of the literature. Int J Prod Econ 152:131–143

Beske P, Seuring S (2014) Putting sustainability into supply chain management. Supply Chain Manage Int J 19(3):322–331

Bigge DM (2004) Bring on the bluewash—a social constructivist argument against using Nike v. Kasky to attack the UN Global Compact. Int Legal Perspect 14(6):6–21

Carter CR, Easton PL (2011) Sustainable supply chain management: evolution and future directions. Int J Phys Distrib Logistics Manage 41(1):46–62

Carter CR, Rogers DS (2008) A framework of sustainable supply chain management: moving toward new theory. Int J Phys Distrib Logistics Manage 38(5):360–387

Cohen WM, Levinthal DA (1990) Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm Sci Q 35(1):128–152

Deva S (2006) Global compact: a critique of the UN’s “public-private” partnership for promoting corporate citizenship. Syracuse J Int Law Commun 34(1):107–151

Dingwerth K, Eichinger M (2010) Tamed transparency: how information disclosure under the global reporting initiative fails to empower. Global Environ Polit 10(3):74–96

Epstein MJ, Roy M-J (2001) Sustainability in action: identifying and measuring the key performance drivers. Long Range Plan 34(5):585–604

Etzion D, Ferraro F (2010) The role of analogy in the institutionalization of sustainability reporting. Organ Sci 21(5):1092–1107

Foerstl K, Reuter C, Hartmann E, Blome C (2010) Managing supplier sustainability risks in a dynamically changing environment—sustainable supplier management in the chemical industry. J Purchasing Supply Manage 16(2):118–130

Gavronski I, Klassen RD, Vachon S, Machado do Nascimento LF (2012) A learning and knowledge approach to sustainable operations. Int J Prod Econ 140(1):183–192

Gold S, Seuring S, Beske P (2010) Sustainable supply chain management and inter-organizational resources: a literature review. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 17(4):230–245

Gopalakrishnan K, Yusuf YY, Musa A, Abubakar T, Ambursa HM (2012) Sustainable supply chain management: a case study of British Aerospace (BAe) Systems. Int J Prod Econ 140(1):193–203

Hartmann J, Moeller S (2014) Chain liability in multitier supply chains? Responsibility attributions for unsustainable supplier behavior. J Oper Manage 32(5):281–294

Helfat C, Finkelstein S, Mitchell W, Peteraf M, Singh H, Teece D, Winter S (2007) Dynamic capabilities: understanding strategic change in organizations. Blackwell, Malden

Hofmann H, Busse C, Bode C, Henke M (2014) Sustainability-related supply chain risks: conceptualization and management. Bus Strategy Environ 23(3):160–172

Hoejmose S, Brammer S, Millington A (2012) “Green” supply chain management: the role of trust and top management in B2B and B2C markets. Ind Mark Manage 41(4):609–620

Jansen JJP, Van Den Bosch, FAJ, Volberda HW (2005) Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: how do organizational antecedents matter? Acad Manage J 48(6):999–1015

Jiang B (2009) The effects of interorganizational governance on supplier’s compliance with SCC: an empirical examination of compliant and non-compliant suppliers. J Oper Manage 27(4):267–280

Kanzer AM (2010) Toward a model for sustainable capital allocation. In: Eccles RG, Cheng B, Salzman D (eds) The landscape of integrated reporting. Reflections and next steps. Harvard Business School, Cambridge, MA

Kaptein M, Wempe J (1998) Twelve Gordian knots when developing an organizational code of ethics. J Bus Ethics 17(8):853–869

Klassen RD, Vereecke A (2012) Social issues in supply chains: capabilities link responsibility, risk (opportunity), and performance. Int J Prod Econ 140(1):103–115

Koplin J, Seuring S, Mesterharm M (2007) Incorporating sustainability into supply management in the automotive industry—the case of the Volkswagen AG. J Clean Prod 15(11):1053–1062

KPMG (2013) The KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting 2013. KPMG Special Services B.V, Netherlands

Large RO, Gimenez Thomsen C (2011) Drivers of green supply management performance: evidence from Germany. J Purchasing Supply Manage 17(3):176–184

Leppelt T, Foerstl K, Reuter C, Hartmann E (2013) Sustainability management beyond organizational boundaries—sustainable supplier relationship management in the chemical industry. J Clean Prod 56:94–102

Levy DL, Brown HS, Jong M (2010) The contested politics of corporate governance: the case of the Global reporting initiative. Business & Society 49(1):88–115

Lichtenthaler U (2009) Absorptive capacity, environmental turbulence, and the complementarity of organizational learning processes. Acad Manage J 52(4):822–846

Meehan J, Bryde D (2011) Sustainable procurement practice. Bus Strategy Environ 20(2):94–106

Messier WF Jr, Martinov-Bennie N, Eilifsen A (2005) A review and integration of empirical research on materiality: two decades later. Auditing J Practice Theor 24(2):153–187

Mollenkopf D, Stolze H, Tate L, Ueltschy M (2010) Green, lean, and global supply chains. Int J Phys Distrib Logistics Manage 40(1/2):14–41

Mueller MV, dos Santos VG, Seuring S (2009) The contribution of environmental and social standards towards ensuring legitimacy in supply chain governance. J Bus Ethics 89(4):509–523

Nolan J (2005) The United Nations’ compact with business: hindering or helping the protection of human rights? Univ Queensland Law J 24(2):445–466

Pagell M, Wu Z (2009) Building a more complete theory of sustainable supply chain management using case studies of 10 exemplars. J Supply Chain Manage 45(2):37–56

Peloza J (2009) The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance. J Manage 35(6):1518–1541

Ramanathan U, Bentley Y, Pang G (2014) The role of collaboration in the UK green supply chains: an exploratory study of the perspectives of suppliers, logistics and retailers. J Cleaner Prod 70:231–241

Sarkis J, Zhu Q, Lai K (2011) An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int J Prod Econ 130(1):1–15

Schleper MC, Busse C (2013) Toward a standardized supplier code of ethics: development of a design concept based on diffusion of innovation theory. Logistics Res 6(4):187–216

Seuring S, Müller M (2008) From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J Cleaner Prod 16(15):1699–1710

Srivastava SK (2007) Green supply-chain management: a state-of-the-art literature review. Int J Manag Rev 9(1):53–80

Vachon S, Klassen RD (2008) Environmental management and manufacturing performance: the role of collaboration in the supply chain. Int J Prod Econ 111(2):299–315

WBCSD (2013) Reporting matters. Improving the effectiveness of reporting. WBCSD Baseline Report 2013. Retrieved from: http://en.vbcsd.vn/upload/attach/WBCSD_Reporting_matters_2013_INT_PDF.pdf. Accessed 1 March 2015

Wu I-L, Chuang C-H, Hsu C-H (2014) Information sharing and collaborative behaviors in enabling supply chain performance: a social exchange perspective. Int J Prod Econ 148:122–132

Zahra SA, George G (2002) Absorptive capacity: a review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad Manage Rev 17(2):185–203

Zhu Q, Sarkis J, Cordeiro JJ, Lai K-H (2008) Firm-level correlates of emergent green supply chain management practices in the Chinese context. Omega 36(4):577–591

Zhu Q, Sarkis J, Lai K-H (2007) Green supply chain management: pressures, practices and performance within the Chinese automobile industry. J Cleaner Prod 15(11–12):1041–1052

Zhu Q, Sarkis J, Lai K-H (2013) Institutional-based antecedents and performance outcomes of internal and external green supply chain management practices. J Purchasing Supply Manage 19(2):106–117

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kjaergaard, T., Schleper, M.C., Schmidt, C.G. (2016). Current Deficiencies and Paths for Future Improvement in Corporate Sustainability Reporting. In: Zijm, H., Klumpp, M., Clausen, U., Hompel, M. (eds) Logistics and Supply Chain Innovation. Lecture Notes in Logistics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22288-2_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22288-2_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-22287-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-22288-2

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)