Abstract

Women who receive positive or uninformative BRCA1/2 test results face a number of decisions about how to manage their cancer risk. The purpose of this study was to prospectively examine the effect of receiving a positive versus uninformative BRCA1/2 genetic test result on the perceived pros and cons of risk-reducing mastectomy (RRM) and risk-reducing oophorectomy (RRO) and breast cancer screening. We further examined how perceived pros and cons of surgery predict intention for and uptake of surgery. 308 women (146 positive, 162 uninformative) were included in RRM and breast cancer screening analyses. 276 women were included in RRO analyses. Participants completed questionnaires at pre-disclosure baseline and 1-, 6-, and 12-months post-disclosure. We used linear multiple regression to assess whether test result contributed to change in pros and cons and logistic regression to predict intentions and surgery uptake. Receipt of a positive BRCA1/2 test result predicted stronger pros for RRM and RRO (P < 0.001), but not perceived cons of RRM and RRO. Pros of surgery predicted RRM and RRO intentions in carriers and RRO intentions in uninformatives. Cons predicted RRM intentions in carriers. Pros and cons predicted carriers’ RRO uptake in the year after testing (P < 0.001). Receipt of BRCA1/2 mutation test results impacts how carriers see the positive aspects of RRO and RRM and their surgical intentions. Both the positive and negative aspects predict uptake of surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

BRCA1/BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) gene testing increasingly has become part of routine clinical care for high-risk women. BRCA1/2 mutations confer a 40–66% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer and a 13–46% risk of ovarian cancer [1]. BRCA1/2 carriers with a previous breast cancer diagnosis have up to a 60% lifetime risk of a second contralateral breast cancer [2, 3]. Thus, women who learn that they carry a BRCA1/2 mutation are faced with difficult decisions about how to manage their cancer risk.

Current guidelines for breast cancer risk management for mutation carriers recommend enhanced breast cancer surveillance with annual mammography and breast magnetic resonance imaging beginning at age 25–30 and consideration of risk-reducing mastectomy (RRM) [4, 5]. Guidelines for ovarian cancer risk management recommend risk-reducing oophorectomy (RRO) at the completion of child-bearing or by age of 35–40 [4]. RRO also reduces breast cancer risk when performed before age 50 [6, 7].

In contrast to mutation carriers, for women who are first in their family to undergo testing (i.e., proband), but for whom a deleterious mutation is not detected, hereditary risk remains uncertain and cannot be ruled out due to the possibility of an undetected BRCA1/2 mutation or a mutation in another cancer susceptibility gene. This result is considered uninformative, accounting for the majority of results received by probands [8]. There are no standard professional guidelines for risk management among uninformatives. Women who do not carry a mutation previously detected in their family receive definitive negative results, with cancer risk and screening guidelines similar to the general population [9, 10].

Cancer risk management decisions can be difficult for women who receive positive or uninformative results, partially due to the competing risks, benefits, and limitations of each management option. Although RRM reduces the risk of breast cancer risk by about 90% in both unaffected and previously affected women [11–13], many women are reluctant to choose RRM due to concerns about body image, sexuality, quality of life, the irreversibility of the procedure, and the aggressive nature of removing healthy breasts. In contrast, breast cancer surveillance is non-invasive with few adverse effects, but does not reduce cancer risk. There is also limited evidence for the efficacy of enhanced surveillance among BRCA1/2 carriers [14]. Finally, while RRO reduces the risk of ovarian and breast cancer when performed pre-menopausally [6, 7, 15], it can lead to severe menopausal symptoms [16] and increased cardiovascular risks due to the loss of protective estrogen [17, 18]. Women from high-risk families who receive uninformative results often consider some or all of these options, but unlike carriers, do not have clear recommendations to guide their management decisions. They must base their decisions on qualitative risk estimates that are informed by their medical history and family pedigree. These estimates are heterogeneous and entail considerable uncertainty, complicating risk management decisions in this population [19].

To date, there has been little quantitative study of how the receipt of BRCA1/2 test results impacts women’s attitudes toward RRM and RRO and how these attitudes impact subsequent risk management decision making. Perceived benefits of RRO predict surgery intentions in women with a family history of the disease [20], and a recent retrospective study showed that attitudes about RRM and screening differed by test result and that these attitudes were related to the ultimate management option [21]. However, we are aware of no prospective studies that have examined the impact of genetic test results on changes in attitudes toward risk management and whether these attitudes impact intentions for and uptake of risk-reducing surgeries.

Therefore, we evaluated the effect of receiving a positive versus uninformative BRCA1/2 genetic test result on the pros and cons of RRM, RRO, and breast cancer screening. We further examined how pros and cons of RRM and RRO predict intention for and, in carriers, subsequent uptake of surgery. We predicted that positive BRCA1/2 test results would lead to more positive attitudes (increased pros and decreased cons) toward RRM and RRO, while these measures would not change significantly for uninformatives. We further predicted that these pros and cons would predict surgical intentions and, among carriers, uptake in the year after testing, adjusting for pre-testing attitudes.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from 2001 to 2005, a period predating the use of routine MRI for high-risk women [22], through the genetic testing research programs at the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and Englewood (NJ) Hospital and Medical Center. Data were collected as part of a randomized controlled trial of a CD-ROM-based decision aid intervention for women who received BRCA1/BRCA2 positive test results, with the aim of facilitating risk management decisions in this group [23].

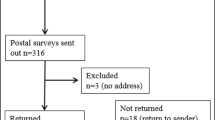

Of the 1223 individuals who contacted the clinical research programs across the sites, 1109 completed a pre-disclosure baseline telephone interview. However, since the pros and cons measures were not initially included in the interview, 603 female participants completed interviews that included the measures. Of these, 408 received either positive BRCA1/2 test results (N = 191) or uninformative results (N = 217). Among these, 31 were ineligible for the present analysis for the following reasons: prior bilateral mastectomy (N = 9); under age 25 (N = 3); or age 75 or older (N = 19). Age restrictions were chosen to coincide with breast cancer screening guidelines for high-risk women [4]. Of the remaining 377 eligible women, 47 (11.75%) did not complete the post-disclosure baseline interview, 18 (4.5%) did not complete the 6-month interview, and 4 (1.0%) did not complete the 12-month interview. Thus, the final sample of 308 represents 81.70% of eligible women.

For analyses focused on RRM and breast cancer screening, the full sample of 308 women (146 positive, 162 uninformative) was available for analysis. For analyses focused on RRO, we eliminated those with prior bilateral oophorectomy, yielding a smaller group (N = 276).

Procedure

All participants were self- or physician-referred to one of the participating genetic counseling programs. Prior to the initial genetic counseling appointment, eligible participants completed a baseline telephone interview and related informed consent to collect information on demographics, family cancer history, psychosocial variables, and attitudes toward risk management options. After providing written informed consent to receive genetic counseling, participants completed an initial genetic counseling session, and, if interested, provided DNA for genetic testing. Participants later completed a genetic counseling disclosure session, during which the test result was disclosed and its implications were discussed with the patient, including associated breast and ovarian cancer risks, options for breast and ovarian cancer prevention and surveillance, psychological issues related to disclosure, and referrals to other medical professionals for recommended follow-up. At 1-month post-disclosure of test results, we recontacted participants to complete follow-up telephone interviews. All genetic counseling and testing were provided free of charge.

With the exception of our behavioral outcomes (RRM/RRO) at 6 and 12 months post-disclosure, data were collected prior to randomization into the decision aid intervention, which was completed after the post-disclosure baseline interview. These participants received standard genetic counseling [24]. Briefly, this included the following topics: risk assessment, cancer risks associated with BRCA1/2 mutations, the process of BRCA1/2 testing and interpretation of results, options for cancer prevention and surveillance, and potential benefits and risks of testing. Participants received their results at a genetic counseling disclosure session during which the implications of their test result and management options were discussed. All carriers were provided with explicit recommendations for breast cancer surveillance, information about other management options, physician referrals, and a summary letter outlining all guidelines and recommendations. Approximately 2–4 weeks post-disclosure, participants were contacted for a brief telephone follow-up in which the genetic counselor answered new patient questions, discussed ongoing concerns, and made additional referrals if indicated.

Data for RRM/RRO outcomes in carriers combined both arms of the decision aid trial. In previous study, we reported that the two groups did not differ on uptake of RRM by 12 months post-disclosure [23]. Similarly, the overall rate of RRO did not differ between the groups at 12 months. Despite this, we included randomization status in our models of RRM/RRO uptake to be conservative.

Measures

Control variables

Sociodemographics

Participants provided the following, which were dichotomized as: age (≤50 vs. >50), race (Caucasian vs. other), marital status (married/partnered vs. other), education (college graduate vs. <college graduate), employment (full time vs. other), insurance status (yes vs. no), and religion (Jewish vs. other).

Medical/family history

Upon entry into the genetic counseling program, we assessed family and personal cancer history, screening behavior, and surgical history.

Pros/cons of risk management options

All pros/cons measures were rated on a 4-point Likert-style scale ranging from 1 (Not at all Important) to 4 (Very Important). In each case, separate pros and cons scales were computed by summing the pros items and cons items, then dividing by the number of items to create mean item scores that would be comparable across scales.

Pros/cons of RRM

We measured seven pros (Prophylactic mastectomy would reduce my worry about breast cancer) and nine cons (I am concerned about the risks of undergoing major surgery) of RRM at pre-disclosure baseline and 1-month post-disclosure. Reliability for pros (α = 0.80–0.81) and cons (α = 0.80–0.84) was excellent.

Pros/cons of RRO

We measured seven pro (To reduce my risk for developing ovarian cancer) and eight con (I am concerned that prophylactic oophorectomy does not eliminate my risk for ovarian cancer) items for RRO at pre-disclosure baseline and post-disclosure. Reliability for pros (α = 0.75–0.78) and cons (α = 0.76–0.77) was acceptable.

Pros/cons of breast screening

Finally, we measured the seven pro (To detect breast cancer early, when it is most treatable) and eight con (I would worry about the risk of mammography missing a cancer that is really present) items for breast screening at post-disclosure only. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76 for pros and 0.70 for cons.

Intentions for RRM and RRO

At pre-disclosure baseline and post-disclosure, we asked participants about their intentions for RRM and RRO. We measured intentions for RRM using two items. Participants were asked: Are you considering having any [additional] breast surgery? (Yes/No). Those who responded yes to this item were asked: What [additional] breast surgery are you considering? Response options included preventive removal of one breast (contralateral mastectomy), preventive removal of both breasts (Bilateral mastectomy), or other surgery (i.e., reconstruction). Responses were coded as Yes if either contralateral or bilateral RRM was being considered.

We measured intentions for RRO using the item, Are you considering having your ovaries removed for prevention? (Yes/No), at each timepoint.

Uptake of RRM and RRO

At the post-disclosure baseline and 6 and 12 months post-disclosure, participants completed a series of questions regarding whether they had received any (additional) breast surgery since the previous interview and, if so, the nature of this surgery. We also asked whether, since our last contact, they had had their ovaries removed, and if so, the reason for this surgery. Participants who received mastectomy or oophorectomy as part of cancer treatment during the follow-up period were not included in the analysis.

Statistical analyses

We used multivariate linear regression to examine whether test result predicted pros and cons of risk management strategies, adjusting for baseline pros and cons and covariates. We used multiple logistic regression to examine whether pros and cons of RRM and RRO at post-disclosure predicted intentions for RRM and RRO, controlling for affected status, baseline pros or cons, baseline intentions, and covariates. Data were analyzed using SPSS 17.0.

Results

Descriptive and bivariate analyses

Mean scores and percentages are shown in Table 1. Younger participants (<50) had stronger pros and cons and weaker intentions for each management option (Ps < 0.001). More-educated participants reported stronger cons for RRM than less-educated participants (t = 3.25, P < 0.001). Married participants had stronger pros (t = 2.24, P < 0.05) and intentions for RRO (χ2 = 4.12, P < 0.05) than unmarried participants. Perceived cons of RRM and RRO were inversely related to the number of lifetime biopsies (r = −0.20, P < 0.001; r = −0.19, P ≤ 0.001) and mammograms (r = −0.24 P < 0.001; r = −0.24, P ≤ 0.001). Jewish women were less likely to be considering RRM (χ2 = 8.78, P < 0.01). We adjusted for these covariates in subsequent models.

Pros and cons toward management options

We examined the association between test result (BRCA1/2 positive vs. uninformative) and change in pros and cons for risk management options, adjusting for baseline pros and cons, covariates, and affected status. Receipt of a positive test result was associated with more positive attitudes toward RRM relative to receipt of an uninformative test result (Fig. 1). Specifically, participants who tested positive reported increased perceived pros for RRM. Test result did not impact perceived cons of RRM. The pattern of results was identical for RRO (Fig. 2). RRO pros increased significantly for mutation carriers as compared to uninformatives. There was no association between test result and perceived RRO cons. As seen in Tables 2 and 3, there were a number of items that changed significantly following testing. For RRM, these primarily dealt with the risk-reducing benefits of surgery and the cons of concerns about the risks of surgery and changes to one’s appearance. The means of few items changed in the context of RRO, with these being concerns about the risks of surgery and concern about self-image. In multivariate linear regression models predicting post-disclosure pros and cons (Table 4), after adjusting for baseline pros and cons, covariates, and affected status, carriers held significantly stronger RRM and RRO pros. Test result did not significantly contribute for the models for cons of surgery.

Although we did not assess screening pros and cons longitudinally, there were significant differences at post-disclosure by test result for screening cons (t = 2.68, P < 0.01), with carriers reporting more negative views of screening (1.70) than uninformatives (1.52). There were not significant group differences for screening pros (3.08 vs. 3.00).

Pros predict intentions for RRM and RRO

Predicting RRM/RRO intentions in carriers, adjusting for affected status, pre-disclosure intentions, pre-disclosure pros or cons, and covariates of religion and education, stronger post-disclosure RRM pros (Table 5, OR = 8.45, 95%CI = 2.75–25.95, P < 0.001) and weaker cons (OR = 0.33, 95%CI = 0.12–0.89, P < 0.05) predicted RRM intentions at post-disclosure. Stronger RRO pros predicted RRO intentions (OR = 10.46, 95%CI = 1.95–56.09, P < 0.001).

In our sample, all uninformatives were cancer-affected. Due to this redundancy, we did not adjust for affected status in our models of intention. Among uninformatives, controlling for pre-disclosure intentions, pros or cons, and covariates of age and marital status, neither pros nor cons of RRM predicted intentions for this surgery. Stronger pros of RRO (OR = 6.97, 95%CI = 2.62–18.55, P < 0.001) predicted RRO intentions in this group.

Pros and cons of RRO predict uptake among carriers

Finally, we assessed whether RRM/RRO pros or cons predicted carriers’ uptake of RRM/RRO in the year post-testing. Nineteen carriers had RRM by 12 months post-testing; 47 carriers had RRO. Adjusting for pre-disclosure pros and cons, age and randomization status, higher pros (OR = 7.84, 95%CI = 2.43–25.25, P < 0.001) and lower cons (OR = 0.13, 95%CI = 0.05–0.37, P < 0.001) of RRO at post-disclosure predicted RRO uptake (Table 6). Intentions at post-disclosure strongly predicted RRM. Neither RRM pros nor cons predicted uptake of surgery.

Discussion

Most women who receive positive or uninformative BRCA1/2 mutation test results face complex and emotion-laden decisions about their breast and ovarian cancer risk management [25]. Given that carriers often do not receive definitive guidance on which risk management strategy is best for them and those with uninformative results do not have formal guidelines to assist their decision making, these decisions must be made based on individual preferences.

We examined whether the receipt of BRCA1/2 genetic test results changes individual preferences, which were measured as perceived pros and cons of risk management strategies. We further evaluated whether these perceived pros and cons predicted short-term intentions for and longer-term uptake of risk-reducing surgery. We found that patient preferences for risk-reducing surgery became more positive following receipt of a positive test result. Specifically, patients who learned that they carry a BRCA1/2 mutation exhibited an increase in the perceived RRM/RRO pros compared to those with uninformative test results. Perceived cons did not change. Further, perceived pros were significantly associated with intentions for RRM/RRO among BRCA1/2 carriers, as were perceived cons with intentions for RRM among carriers. Finally, pros and cons in carriers prospectively predicted uptake of RRO in the year post-testing.

It is unclear why the perceived pros of surgeries were more likely to change than the cons and to predict intentions. It may capture discussions had with both medical and genetic counseling providers, in which providers may counsel carriers about the advantages of RRO for this high-risk group. Also, early studies of attitudes toward RRM/RRO found that increased worry predicted surgical intentions [26–28], which is captured in our pros scale. Also, unfortunately, many of the disadvantages of the surgeries do not change—even in women inclined toward surgery, the importance of these risks does not seem to dissipate. Rather, it appears that the relative advantages of these surgeries in terms of risk-reduction may truly increase following a positive result. As a result, pros may come to outweigh cons. Our data also indicate that carriers view screening more negatively than uninformatives at post-disclosure. Thus, it may be that in considering risk management options following the receipt of a positive result, RRM pros (reducing future cancer risks) and screening cons (missing a cancer that is present) may become more pronounced, as might the related differences between prevention versus early detection.

Our study also showed the potential value of measuring preferences for risk-reducing surgery post-disclosure. Perceived pros and cons predicted subsequent uptake of RRO, even after controlling for post-disclosure RRO intentions. This suggests that for women who are initially ambivalent or undecided, those with the strongest preferences are most likely to ultimately proceed with RRO. This may also suggest that those with the strongest preferences may be most likely to obtain RRO in the year post-testing. Women who were more ambivalent, i.e., those who viewed the pros and cons of surgery as equivalent, may delay surgery. Longer-term data would be needed to examine these trends. It also suggests that when predicting actual behavior, the cons of surgery do enter into these decisions. Those who hold stronger reservations about surgery may still hesitate to move forward with this important decision.

Our low overall rate of RRM is consistent with previous reports documenting low RRM uptake in the year post-testing [29, 30]. This low rate of RRM may explain the lack of an association between pros/cons and RRM uptake. Recent studies suggest increasing use of RRM [31–33] and ongoing uptake of RRM after the first year following testing [23]. Likewise, guidelines now include enhanced screening [4, 5]. Since our data were collected from 2001 to 2005, the rates of RRM may be different if the data were collected today. Further, it is likely that more carriers opted for RRM in subsequent years. We did detect an association between pros/cons and intentions, though the strongest predictor of intentions for and uptake of RRM were previous intentions. It may be that women inclined toward surgery at pre-disclosure baseline remain so after the receipt of test results and that the receipt of a positive test result does not make women who are disinclined to RRM more amenable. A substantial literature shows how intentions relate to behaviors in terms of timing and behavioral context [34, 35]. Perhaps given the perceived aggressive nature of RRM, any changes in pros/cons of RRM may not be able to predict uptake of RRM above and beyond the contribution of intentions. However, behavioral outcomes for RRM should be evaluated in datasets that follow surgical outcomes for longer than 12 months post-testing to determine the longer-term relationships among these variables.

This study has several limitations. Although the overall sample size was large, few women received RRM in the year post-testing. Thus, we were unable to determine whether changes in pros and cons about RRM ultimately predicted behavior. In addition, all of our uninformatives were cancer-affected. We are unable to comment on potential results for unaffected women with these results or to look at the impact of affected status in models of intention for uninformatives. Also, we did not assess pros and cons of breast screening at pre-disclosure baseline. Therefore, we were unable to examine the change in these over time or to fully assess whether and how changes in pros and cons of screening and surgery relate. Also, because our data at 6 and 12 months post-disclosure were gathered in the context of a randomized trial, our measures of uptake must be considered in this context. Though we controlled to randomization status in our models for surgery uptake, the data for which were collected after randomization, we must consider that findings in purely clinical settings may vary. Also, there are certain aspects of our pros/cons measures that are weaknesses. The fact that our data were collected from 2001 to 2005, our screening measure does not capture more recent advances in screening that could potentially impact our findings. Also, while our cons of RRO reference menopausal symptoms, they do not specifically ask women about this important con. The time period of our data collection also limited our ability to examine rates of enhanced screening. Finally, the lack of diversity of the study sample limits the generalizability of these results. In particular, the vast majority of study participants were well-educated, employed and White. Thus, we do not know whether these results could be replicated in a sample of more racially and ethnically diverse or lower SES women. Also, our results may not generalize to community samples [36].

Despite these limitations, the present report demonstrates that the receipt of BRCA1/2 mutation test results impacts how mutation carriers see the positive aspects of RRO and RRM, and further that these positive aspects predict intentions for surgery. Pros and cons predict uptake of RRO in carriers. Future research should follow women further in time to better capture behavioral outcomes.

References

Chen S, Parmigiani G (2007) Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol 25:1329–1333

Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium (1999) Cancer risks in BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:136–1310

Metcalfe K, Lynch HT, Ghadirian P et al (2004) Contralateral breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol 22:2328–2335

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2009) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. v.1.2009. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/genetics_screening.pdf. Accessed 27 Jan 2010

Smith KL, Robson ME (2006) Update on hereditary breast cancer. Curr Oncol Rep 8:14–21

Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME et al (2002) Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med 346:1609–1615

Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL et al (2002) Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med 346:1616–1622

Vink GR, van Asperen CJ, Devilee P et al (2005) Unclassified variants in disease-causing genes: nonuniformity of genetic testing and counselling, a proposal for guidelines. Eur J Hum Genet 13:525–527

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2009) NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. v.1.2010. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/breast-screening.pdf. Accessed 27 Jan 2010

Domchek SM, Gaudet MM, Stopfer JE et al (2009) Breast cancer risks in individuals testing negative for a known family mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2. Breast Cancer Res Treat 119:409–414

Herrinton LJ, Barlow WE, Yu O et al (2005) Efficacy of prophylactic mastectomy in women with unilateral breast cancer: a cancer research network project. J Clin Oncol 23:4275–4286

McDonnell SK, Schaid DJ, Myers JL et al (2001) Efficacy of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in women with a personal and family history of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 19:3938–3943

Peralta EA, Ellenhorn JD, Wagman LD et al (2000) Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy improves the outcome of selected patients undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer. Am J Surg 180:439–445

Tilanus-Linthorst M, Verhoog L, Obdeijn IM et al (2002) A BRCA1/2 mutation, high breast density and prominent pushing margins of a tumor independently contribute to a frequent false-negative mammography. Int J Cancer 102:91–95

Rebbeck TR, Kauff ND, Domchek SM (2009) Meta-analysis of risk reduction estimates associated with risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:80–97

Madalinska JB, Hollenstein J, Bleiker E et al (2005) Quality-of-life effects of prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy versus gynecologic screening among women at increased risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:6890–6898

Parker WH, Jacoby V, Shoupe D et al (2009) Effect of bilateral oophorectomy on women’s long-term health. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 5:565–576

Verhoeven MO, van der Mooren MJ, Teerlink T et al (2009) The influence of physiological and surgical menopause on coronary heart disease risk markers. Menopause 16:37–49

Rini C, O’Neill SC, Valdimarsdottir H et al (2009) Cognitive and emotional factors predicting decisional conflict among high-risk breast cancer survivors who receive uninformative BRCA1/2 results. Health Psychol 28:569–578

Fang CY, Miller SM, Malick J et al (2003) Psychosocial correlates of intention to undergo prophylactic oophorectomy among women with a family history of ovarian cancer. Prev Med 37:424–431

Litton JK, Westin SN, Ready K et al (2009) Perception of screening and risk reduction surgeries in patients tested for a BRCA deleterious mutation. Cancer 115:1598–1604

Warner E, Messersmith H, Causer P et al (2008) Systematic review: using magnetic resonance imaging to screen women at high risk for breast cancer. Ann Intern Med 148:671–679

Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, DeMarco TA et al (2009) Randomized trial of a decision aid for BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: impact on measures of decision making and satisfaction. Health Psychol 28:11–19

Schwartz MD, Peshkin BN, Hughes C et al (2002) Impact of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation testing on psychologic distress in a clinic-based sample. J Clin Oncol 20:514–520

Schwartz MD, Peshkin BN, Tercyak KP et al (2005) Decision making and decision support for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer susceptibility. Health Psychol 24:S78–S84

Meiser B, Butow P, Barratt A et al (1999) Attitudes toward prophylactic oophorectomy and screening utilization in women at increased risk of developing hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 75:122–129

Meiser B, Butow P, Friedlander M et al (2000) Intention to undergo prophylactic bilateral mastectomy in women at increased risk of developing hereditary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 18:2250–2257

van Dijk S, Otten W, Zoeteweij MW et al (2003) Genetic counselling and the intention to undergo prophylactic mastectomy: effects of a breast cancer risk assessment. Br J Cancer 88:1675–1681

Botkin JR, Smith KR, Croyle RT et al (2003) Genetic testing for a BRCA1 mutation: prophylactic surgery and screening behavior in women 2 years post testing. Am J Med Genet A 118A:201–209

Peshkin BN, Schwartz MD, Isaacs C et al (2002) Utilization of breast cancer screening in a clinically based sample of women after BRCA1/2 testing. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11:1115–1118

Arrington AK, Jarosek SL, Virnig BA et al (2009) Patient and surgeon characteristics associated with increased use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy in patients with breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 16:2697–2704

Jones NB, Wilson J, Kotur L et al (2009) Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy for unilateral breast cancer: an increasing trend at a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol 16:2691–2696

McGuire KP, Santillan AA, Kaur P et al (2009) Are mastectomies on the rise? A 13-year trend analysis of the selection of mastectomy versus breast conservation therapy in 5865 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 16:2682–2690

Sheeran P (2002) Intention-behavior relations: a conceptual and empirical review. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 12:1–36

Fishbein M, Hennessy M, Kamb M et al (2001) Using intervention theory to model factors influencing behavior change. Project RESPECT. Eval Health Prof 24:363–384

Morgan D, Sylvester H, Lucas FL et al (2009) Cancer prevention and screening practices among women at risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer after genetic counseling in the community setting. Fam Cancer 8:277–287

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Cancer Institute Grant RO1 CA01846 (MDS). The authors would like to thank Michael Green and Lisa Moss for their contributions to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Neill, S.C., Valdimarsdottir, H.B., DeMarco, T.A. et al. BRCA1/2 test results impact risk management attitudes, intentions, and uptake. Breast Cancer Res Treat 124, 755–764 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-0881-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-0881-4