Abstract

We examined interactions among genetic, biological, and ecological variables predicting externalizing behaviors in preschool and middle childhood. Specifically, we examined prediction of externalizing behaviors from birth complications and negative emotionality, each moderated by genetic risk for aggression and ecological risk factors of insensitive parenting and low family income. At ages 4 and 5 years, 170 twin pairs and 5 triplet sets (N = 355 children) were tested; 166 of those children were tested again at middle childhood (M = 7.9 years). Multilevel linear modeling results showed generally that children at high genetic risk for aggression or from low-income families were likely to have high scores on externalizing, but for children not at high risk, those with increased birth complications or more negative emotionality had high scores on externalizing. This study underscores the importance of considering biological variables as moderated by both genetic and ecological variables as they predict externalizing behaviors across early childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Externalizing behaviors include antisocial acts, often targeted at others but sometimes targeted at oneself (Kauten and Barry 2020). Researchers have used a variety of definitions for externalizing behaviors; in this paper, we include aggression (e.g., hitting) and conduct problem behaviors (e.g., rule-breaking; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). There is clear evidence of biological influences on childhood externalizing problem behaviors (Dhamija et al. 2016). Much evidence also supports the pervasive negative impact that adverse experiences such as poor parenting practices (Pinquart 2017) and economic hardship (Letourneau et al. 2013; Nobile et al. 2007) have on the development of externalizing behavior in childhood through both environmental and genetic pathways, including correlations and interactions between environments and genes. The current study used a longitudinal, genetically informed design to investigate biological and ecological contributors to externalizing behaviors in childhood, including birth complications, child temperament, genetic risk, and observational parent measures. We additionally examined the interactive effects that these contributors have on externalizing behaviors at both preschool and middle childhood, as per the bioecological model (Bronfenbrenner and Morris 2006), thus shedding light on factors that may place young children at greater risk for externalizing problems across early development.

Biological bases of childhood externalizing problem behaviors

Externalizing behaviors have been shown to be related to several biological influences in early childhood. Genetic factors account for about 50% of the variance in children’s externalizing behaviors, with shared and nonshared environmental influences accounting for approximately 30% and 20%, respectively (Hicks et al. 2013; van der Valk et al. 2003). In addition, two other biologically based characteristics, birth complications and negative emotionality, are related to later externalizing behaviors.

Birth complications can occur during the perinatal period, which encompasses the last few weeks before birth, the birth itself, and several weeks post-birth. Birth complications include any condition or complication that causes stress to the developing fetus or newborn infant (Liu et al. 2009), such as preterm birth, low birth weight, preeclampsia, Caesarean section, and irregular fetal positions such as breech birth. Although the cause of the complication may be environmental (e.g., maternal smoking), the birth complication itself is the physical trauma that the infant experiences. Birth complications are associated with later behavioral problems such as aggression (LaPrairie et al. 2011), conduct problems (Marceau et al. 2019), negative emotionality (Bersted and DiLalla 2016), and externalizing behaviors (Liu 2004; Liu et al. 2009). Less is known about how these effects are moderated by other genetic and family variables, such as genetic risk for aggression, parenting, and family socioeconomic status (SES). Children who experience an early health risk may be more vulnerable than those without health risks to other adverse experiences, such as poor parenting or economic hardship (e.g., Jaekel et al. 2015), consistent with the diathesis-stress model, in which individuals with a biological risk experience more negative outcomes in negative environments compared to those without the biological risk. Similarly, the Early Health Risk Framework (EHRF; Liu 2011) postulates that early health risks, such as birth complications, occur as the result of early biological and psychosocial processes, which may place individuals at risk for negative behavioral problems later in life. This perspective underscores the need to investigate both independent and interactive effects of early health risks and family psychosocial adversity.

Temperament refers to biologically-based individual differences in activity, attention, self-regulation, and emotionality (Shiner et al. 2012). Children high on the temperamental trait of negative emotionality may be more likely to aggress against others or break rules (Eisenberg et al. 2009). A substantial proportion of the genetic factors underlying externalizing problems are shared by negative emotionality (Mikolajewski et al. 2013; Rhee et al. 2015; Singh and Waldman 2010). The effect of negative emotionality on externalizing behaviors appears to be partially mediated (Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al. 2008) and moderated (Bradley and Corwyn 2008) by aspects of the parenting environment. In 3-year-old children, maternal authoritative parenting behaviors (acceptance, consistency, induction, and responsiveness) partially mediated the association between negative emotionality and externalizing behaviors (Paulussen-Hoogeboom et al. 2008). Moderation has been demonstrated in that children with difficult temperaments exposed to high levels of maternal sensitivity and household enrichment showed a significant reduction in externalizing behaviors, but this was not shown for children with easy temperaments (Bradley and Corwyn 2008). Consistent with a diathesis-stress hypothesis, children who are high on negative emotionality should experience poor outcomes in conjunction with other stressors, such as insensitive parenting or lower socioeconomic households (Bradley and Corwyn 2008). Considering genetic and other biological influences on childhood externalizing behaviors is not only critical to understanding the manifestation of these behaviors, but also can inform future work on how to reduce or prevent the likelihood of their occurrence.

Ecological factors and childhood externalizing problem behaviors

Many studies support the detrimental impact that adverse environmental experiences such as family instability and unsupportive parenting (Coe et al. 2019), maternal insensitivity (Wang et al. 2013), and economic hardship (NICHD Research Network 2005) have on children’s behavioral development. The association between child externalizing behavior and parenting behaviors is well-supported. A meta-analysis concluded that parental warmth, authoritative parenting, and parent–child reciprocity are important predictors for decreased externalizing behaviors in childhood (Pinquart 2017), although the bidirectional nature of these associations must be acknowledged (Grusec 2011; Pinquart 2017). One twin study provided evidence for shared genes between insensitive parenting in early childhood and externalizing behaviors in early adolescence for boys but not girls (Boeldt et al. 2012); for girls, the measures were correlated via shared common environment. A monozygotic (MZ) twin differences study, which uses differences between MZ twins to control for genetic and shared environmental factors in order to examine nonshared environmental factors (Pike et al. 1996), showed that the nonshared environment plays an essential role in the relationship between harsh parenting and both child aggression and callous unemotional traits (Waller et al. 2018). Clearly, parenting is related to different types of externalizing behaviors, although much remains to be learned about the underlying mechanisms of transmission. Additionally, little is known about how parenting may moderate existing risks children may have for externalizing behaviors, such as birth complications or difficult temperament, especially for preschoolers.

As with parenting, a robust literature supports the negative influence that disadvantaged socioeconomic status (SES) has on childrearing environments (NICHD Research Network 2005), in addition to children’s biological and socioemotional development (Aber et al. 2012; Bradley and Corwyn 2002). The detrimental effect of poverty has been found within the United States (Peverill et al. 2021), in Japan (Hosokawa and Katsura 2018), and across varying cultural groups from countries of differing income levels (Lansford et al. 2019). Specifically, income loss has been associated with high externalizing behaviors across the U.S. (Miller and Votruba-Drzal 2017) and eight different countries (Lansford et al. 2019). Although the pervasive risk that disadvantaged SES poses to children and families is clear, less is known about how SES might interact with individual differences, like temperament, to affect externalizing behaviors.

Gene-environment interplay and externalizing behaviors

The combined effect of genes and environment plays a critical role in the development of externalizing behaviors (DiLalla 2002), which may occur in different ways. The negative effect of early health risks may have greater consequences in the presence of psychosocial adversity, as supported by a recent meta-analysis demonstrating that preterm birth indirectly predicted socioemotional outcomes in childhood via parent intrusiveness (Toscano et al. 2020). Relatedly, individual differences in childhood conduct problems have been shown to be largely influenced by the common family environment in high-risk contexts, whereas genetic factors were the primary influence in low-risk settings (Burt and Klump 2014; Hendriks et al. 2020). Unlike a diathesis-stress model, which emphasizes genetic vulnerabilities, these results support a bioecological gene-environment interaction model, indicating that some environments may be so adverse that genetic influences are effectively diminished.

Genes and environments exert changing influences across the lifespan, making it difficult to uncover specific influences at any given time (Briley et al. 2019). However, by employing a genetically informed longitudinal design, a more comprehensive study of the potential factors underlying behavioral development can be conducted. Incorporating ecological variables such as SES will provide critical information that may be generalizable to a larger population (Bellani et al. 2013). The current study follows these recommendations and examines the biological, genetic, and ecological influences of externalizing behaviors across development.

The present study

We utilized a longitudinal sample of twins tested from preschool through middle childhood to examine the effects of birth complications and temperament on child externalizing problem behaviors, with a consideration of the possible moderating effects of genetic risk for aggression as well as parenting and household income. By using a longitudinal sample, we were able to examine observed aggression and parenting at age 4 as they predicted externalizing behaviors at age 5 and middle childhood (6–11 years) without relying on retrospective reports. The genetically informed twin sample allowed us to calculate a genetic index of aggression at age 4, which was used as a potential predictor of externalizing problem behaviors.

First, we examined these relationships for 5-year-old externalizing behaviors. We hypothesized that birth complications and negative emotionality would be predictive of externalizing problems, and, further, that these relationships would be moderated by genetic risk for behaving aggressively and family risk (receiving less sensitive parenting or coming from a low-income home). That is, children with more birth complications or greater negative emotionality who also experience one of the moderating risks were expected to be at the highest risk for exhibiting externalizing behaviors.

Second, we examined these relationships for older children’s externalizing behaviors, thus considering externalizing longitudinally. After partialling out variance attributable to earlier externalizing, we hypothesized that children who had experienced more birth complications or who scored higher on negative emotionality would continue to exhibit more externalizing problem behaviors at middle childhood, and that these relationships would continue to be moderated by genetic risk for aggression and by family risk.

Methods

Participants

Participants included children from the longitudinal Southern Illinois Twins/Triplets and Siblings Study (SITSS; DiLalla et al. 2013; DiLalla and Jamnik 2019), an ongoing project examining young children’s social and cognitive development. Children with complete data at ages 4 and 5 were included, providing a sample of 355 children (55% girls). This sample includes 60 monozygotic (MZ) twin pairs, 67 same-sex dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs, 43 opposite-sex DZ twin pairs, and 5 triplet sets (1 MZ set, 3 DZ sets, and 1 mixed MZ/DZ set). All families lived within a 2-h drive of a rural, midwestern university. Participating families reported race/ethnicity as 91% Caucasian, 3% African American, 3% Asian, and 4% other. Maternal education ranged from no completed high school education (4.2%) to having an advanced degree (13.2%), with a median of 43.3% having a college degree. Family yearly income (adjusted to 2020 dollars) ranged from less than $5000 (0.6%) to greater than $90,000 (7.3%), with the median yearly income being $55,000–$60,000 (41.5%).

A subset of the present sample was tested once in one of several follow-up studies when they were older (N = 166 children) between ages 6 to 11 (M = 7.86, SD = 1.61), referred to as the middle childhood sample throughout this document. MANOVA comparison showed that children from the follow-up sample did not differ from those who did not participate at follow-up on any of the preschool study variables, F(4,350) = 0.37, p = .830. All parents gave informed consent prior to study participation, and older children gave assent. Studies were approved by the university Institutional Review Board prior to any data collection.

Procedure

Children were tested at a campus laboratory within one month of their fourth birthdays and within two months of their fifth birthdays. Families were mailed questionnaires that parents completed and brought with them to the test session. During testing, each child was tested individually, and then one parent and their children participated in a parent–child interaction task, which was video-recorded for later coding. Upon completing testing, each child was given a book and toys, and parents were mailed $50 after age 5 testing. Although follow-up studies varied, all included parental questionnaires with the same measure of child externalizing behaviors, which was the measure used for the current study.

Measures

Zygosity

Buccal cell data were collected from 95% of children during at least one test session. Parents swabbed children’s cheeks three times during testing (prior to testing, before parent–child interaction, and at the end of the test session) for 20 s to ensure an adequate DNA sample. Samples were labeled and frozen until they were sent out for analysis. These samples were used to classify pairs as monozygotic (MZ) or dizygotic (DZ). All same-sex pairs also were rated by parents and testers at every test session between the ages of 1 and 5 years on a questionnaire of phenotypic similarity (e.g., hair and eye characteristics) and whether parents, relatives, or others frequently confuse the twins (Nichols and Bilbro 1966). When compared to DNA samples, similarity rating measures have shown high accuracy (94%) in determining zygosity in this sample (DiLalla and Jamnik 2019).

Family demographics

Parents completed a demographic form providing information on race, parental education, and family income. Family income was rated using a 19-point scale, ranging from 1 = less than $5000, to 10 = $45,000–50,000, to 19 = over $90,000. Because these income data were collected over many years, income was adjusted to 2020 values so that income was comparable across families. Parental education, used only to describe the sample, was rated on a 5-point scale (1 = some high school to 5 = advanced degree beyond college education).

Birth complications

A birth complications record was completed by parents at their first testing session to assess the prenatal, perinatal, and neonatal environment (DiLalla et al. 2020). Parents provided information about children’s birth weight, predicted due date, actual birth date, length of hospitalization after birth, and maternal smoking habits. An open-ended question asked parents to list all problems or complications that occurred during birth or pregnancy for each child. A weighted coding scheme to score these variables was developed, informed by other birth complications measures (e.g., Hodgins et al. 2001), that assigns a weighted value to each problem or complication based on how much risk the condition is likely to pose to the infant. A score of 1 indicates the complication was likely not harmful (Mild Level 1), a score of 2 denotes the complication was more likely to cause harm (Moderate Level 2), and a score of 3 signifies the complication was potentially very harmful (Severe Level 3). The total number of weighted items was summed to create a total birth complications score. This coding scheme has shown high test-rest reliability and strong validity compared to hospital records (DiLalla et al. 2020).

Parenting insensitivity

At age 4, after individual testing and after parents and children were acclimated to the lab environment, one parent and both twins (or three triplets) were asked to play with puzzles in any way that they liked for 10 min in an otherwise empty room. They were told that the puzzles were difficult and they might not be able to complete them but they should try. Families were video-recorded; behaviors were later rated by trained, reliable coders using the Parent–Child Interaction Scheme (PCIS; DiLalla et al. 2013) to rate 10 parenting behaviors observed during the 10-min parent–child interaction task. Coders rated behaviors each minute, and a single score for each behavior was created by averaging across the 10 min. For this study, parent insensitivity was investigated. This was scored using a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 = attends quickly to child’s needs; many positive responses to children’s cues to 4 = ignores child or responds harshly to child. A different rater coded each child within a twin or triplet set to eliminate rater bias across siblings. The inter-rater reliability for this scale, calculated as a weighted kappa (Cohen 1968), which takes into account frequency of behavior response options, was good, kappa = .84. The insensitivity variable was significantly skewed, with most parents showing few insensitive behaviors, but sufficient variance existed to include this variable in analyses (range = 1 to 3.6). For 8 pairs, age 4 data were missing (families were not tested that year or there was equipment failure), so age 3 data were used instead. The correlation across the entire SITSS sample for age 3 and age 4 insensitivity was small but significant, r(261) = .15, p = .013.

Child aggression

Child behavior during the age 4 parent–child interaction was coded for a measure of child aggression, also from the PCIS. Children were coded as engaging in aggression if they grabbed a toy, kicked, pushed, pulled, or engaged in any action that was negative in affect and involved physical aggression toward a person or object. The number of times an act of aggression occurred was counted for each child. To minimize rater bias, a different rater coded each child within each twin or triplet set. Inter-rater reliability for this code was good; Cronbach’s weighted alpha = .94. As noted above, for 8 pairs, age 4 data were missing, so age 3 data were used instead. The correlation across the entire SITSS sample for age 3 and age 4 aggression was small but significant, r(266) = .36, p < .001.

Child negative emotionality

At age 5, parents rated children’s temperament using the Behavioral Style Questionnaire (BSQ; McDevitt and Carey 1978). The BSQ is a 100-item measure that provides scores across nine categories of temperament, including Activity Level, Rhythmicity, Adaptability, Approach/Withdrawal, Threshold, Intensity, Mood, Distractibility, and Persistence. The current study specifically focused on Negative Emotionality, created by averaging scores on the Adaptability, Intensity, and Mood scales (Bersted and DiLalla 2016). A 6-point scale, ranging from 1 = almost never to 6 = almost always, is used to rate each item; example items from each of these three scales, respectively, include: “The child is slow to adjust to changes in household rules,” “The child responds intensely to disapproval,” and “The child cries or whines when frustrated.” The three scales forming the Negative Emotionality factor show adequate validity and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .79) at age 5 (Bersted and DiLalla 2016).

Externalizing problems

The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001) was used to measure children’s externalizing problem behaviors at age 5 and again at the middle childhood follow-up studies. The CBCL is a standardized parent-report measure used for screening social, emotional, and behavioral problems. Parents rate their child on 113 items over the past 6 months using a 3-point scale (0 = never true, 1 = sometimes true, 2 = very/often true). For the present study, the higher order factor of externalizing problem behaviors, composed of rule breaking and aggression, was used for analyses. Raw scores were used for all analyses, as is appropriate for a non-clinical sample. The CBCL demonstrates adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas range from .78 to .97), high test–retest reliability (r’s ranging from .95 to 1.00), and high inter-rater reliability (r’s ranging from .93 to .96; Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). The externalizing problems factor displayed good internal consistency in the current sample, Cronbach’s α = .87 at age 5, .86 at middle childhood. This sample was representative of a non-clinical community sample; only 3% of girls and 6% of boys scored at the clinically significant level (T-score of 70 or greater) at age 5, and 0% of girls and 5% of boys scored at this level at middle childhood.

Analysis plan

Aggression genetic risk index

An aggression genetic risk index (AGRI) was created from the age 4 aggression scores coded during the parent–child interaction session, in a manner similar to Jaffee et al. (2005), but using continuous data as was done in DiLalla et al. (2015). Prior to creating a genetic index, the aggression scores were examined to determine whether there was a significant genetic component. Using umx version 3.6 (Bates et al. 2019), the best fitting model was an AE model, with additive genetic variance = .19, nonshared environmental variance = .81.

Eighty-six percent of children showed no aggression during the age 4 parent–child interaction; thus, the cut-off for aggression that was used to calculate the AGRI was one or more aggressive behaviors. The AGRI was calculated for each child as a function of the cotwin’s aggression and their genetic relatedness. MZ twins whose cotwin had an aggression score of 1 or greater were given an AGRI score of 3 because they are genetically most likely to be similar to their cotwin and therefore aggressive (5.9%). DZ twins with a cotwin who scored 1 or greater on aggression were given an AGRI score of 2 because they were genetically at risk of aggression but less so than MZ cotwins (8.4%). DZ twins whose cotwin showed no aggression were given an AGRI score of 1 (56.6%) because they are at decreased genetic risk of aggression compared to DZ twins whose co-twins are aggressive. Finally, MZ twins whose cotwin showed no aggression were given the lowest AGRI score of 0, as they were genetically the least at risk of aggression (29.1%).

Externalizing behaviors

Externalizing at middle childhood was assessed at different ages across families, ranging from 6 to 11 years. Therefore, scores for externalizing behaviors were residualized on age, following methods by McGue and Bouchard (1984), and this measure was used for analyses.

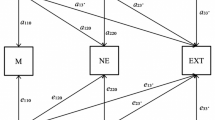

Multilevel linear modeling

Multilevel linear models (MLM), with children nested within families, were used to investigate effects of early biological and family environmental variables on child externalizing behaviors. Analyses were conducted first predicting 5-year-old externalizing behaviors. The independent variables were birth complications and negative emotionality. The moderators were aggression genetic risk index (AGRI), parent insensitivity, and family income. Sex of child was included as a covariate. The first MLM included the birth and genetic measures (birth complications, sex, and AGRI), the second model added age 5 child temperament, and the third model added the two family environment measures (parent insensitivity and family income). Finally, moderation was assessed by including interactions, one at a time, between the independent variables (birth complications and negative emotionality) and the moderators (AGRI, parent insensitivity, and family income). The best fitting model was the one with the lowest Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and most parsimonious fit as shown by a significant improvement in fit when comparing -2LL across models. Any significant interaction effects were probed using the Johnson–Neyman (JN) method (Carden et al. 2017), which works well for continuous moderator variables. The CAHOST Excel 2013 workbook was used (Carden et al. 2017), which provides a graph showing confidence bands. Where the bands are above zero, the effects of the moderator variable are significant.

The second hypothesis examined predictability of middle childhood externalizing, also tested with MLM. The first model included 5-year-old externalizing behaviors, to control for stability of this behavior, as well as the birth and genetic measures of sex, birth complications, and AGRI. The second model added negative emotionality measured at age 5. The third model added family environment (parent insensitivity at age 4 and family income). Interactions were tested one at a time between the independent variables (birth complications and negative emotionality) and the moderators (AGRI, parent insensitivity, and family income). The best fitting model was the one with the lowest Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) and most parsimonious fit as shown by a significant improvement in fit when comparing − 2LL across models. Again, significant interaction effects were probed using the Johnson–Neyman (JN) method (Carden et al. 2017).

Results

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. Externalizing behaviors at age 5 and middle childhood were positively skewed. Square root transformations completely eliminated the skew; these transformed variables were used in all analyses. The Spearman’s rho correlation between sex and 5-year-old externalizing was significant; t test showed a trend for boys to have higher externalizing scores than girls, t(353) = 1.92, p = .056. Thus, sex was included in all analyses.

Predicting 5-year-old externalizing problem behaviors

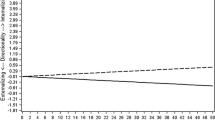

Multilevel linear modeling was used to assess predictors of 5-year-old externalizing behaviors (see Table 2). Analyses showed that birth complications significantly predicted increased externalizing behaviors in model 1, but this was no longer significant after negative emotionality was added in model 2. Model fit improved again in model 3 when parent insensitivity was added, but the best fitting model is presented in model 4, which includes the significant interaction of negative emotionality and family income. In this final model, boys showed more externalizing behaviors than girls, and children who experienced greater parental insensitivity were more likely to exhibit externalizing behaviors. There was a significant interaction between negative emotionality and family income, which was probed using the J–N method (Carden et al. 2017). This showed that as income decreased, children with greater negative emotionality were more at risk of being rated higher on externalizing behaviors (see Fig. 1). This was significant across all levels of family income.

a Johnson–Neyman figure of family income (centered) as moderator of negative emotionality (NE) predicting externalizing age 5 (square rooted). As income increases, NE becomes less predictive of externalizing behaviors. b Simple slope showing that with lower family income, children with higher NE have more externalizing behavior problems; this effect is less significant in families with higher income

Predicting middle childhood externalizing problem behaviors

MLM analyses were repeated, this time with middle childhood externalizing behaviors as the dependent variable, adding 5-year-old externalizing behaviors as an initial independent variable to control for stability of the behavior. Thus, these analyses examined predictors of 6- to 11-year-old externalizing behaviors that accounted for variance beyond what was accounted for by the 5-year-old behaviors. As shown in Table 3, externalizing is a fairly stable behavior; age 5 externalizing behaviors significantly predicted middle childhood externalizing behaviors. The other child and parenting variables did not account for additional variance except for family income, which was significant in model 3; however, that model provided a worse fit to the data compared to model 2. The best fitting model, though, was model 4, which included two interaction effects: negative emotionality by AGRI and birth complications by family income.

Both interactions were probed using the J–N method. For negative emotionality by AGRI (see Fig. 2), the significant interaction occurred for children with low genetic risk of aggression; for those children, as negative emotionality increased, so did externalizing behaviors. Children at high genetic risk for aggression showed a generally higher rate of externalizing behaviors regardless of their score on negative emotionality (see Fig. 2b). For the birth complications by family income interaction (Fig. 3), note that family income was centered, so the significant part of the interaction occurs for families with moderate to fairly high incomes. For children in those families, those with more birth complications were at risk for having higher externalizing behavior scores. Children from low family income homes were more at risk of having higher externalizing scores regardless of number of birth complications (see Fig. 3b).

a Johnson–Neyman simple slope of AGRI moderating negative emotionality (NE) on middle childhood externalizing (square-rooted). The significant area is only for children with low genetic risk for aggression. b Simple slope showing that with low genetic risk of aggression, more NE → more externalizing problems, but with high genetic risk, there is a steady higher rate of externalizing

a Johnson–Neyman simple slope of family income (shown here centered) moderating birth complications on middle childhood externalizing (square-rooted). The significant area is only for families above average for income, but not at the highest level of income. b Simple slopes showing that for families with lower income, externalizing tends to be higher regardless of birth complications. For families with higher incomes, more birth complications are related to increases in middle childhood externalizing problems

Discussion

We examined birth complications and negative emotionality as predictors of externalizing problem behaviors, taking into account potential interactions with a genetic risk for aggression and the ecological risks of parental insensitivity and family income. We found significant interactions showing that risk for externalizing problems was conferred by a complex constellation of biological factors and ecological factors. Results suggested a type of interaction in which high levels of a risk moderator variable are generally sufficient for the development of externalizing problems, but in the absence of this, a predisposing biological risk factor plays an influential role. This differs from diathesis-stress, as both diathesis and stress are not necessarily required for a negative outcome, but it does fit within a bioecological framework, highlighting the importance of both biological and ecological risk factors and their interactions in the development of externalizing behaviors in young children.

Effects of negative emotionality on externalizing behavior

Negative emotionality was a significant predictor of 5-year-old externalizing behaviors, but this effect was no longer independently influential by middle childhood. Negative emotionality clearly had a significant impact on preschool externalizing behaviors. However, for older children, the effects of negative emotionality on externalizing behaviors were significantly moderated by genotype. Specifically, children at high genetic risk for aggression had uniformly high externalizing problems. However, for children at low genetic risk for aggression, the negative effects of negative emotionality were expressed, such that children with high negative emotionality were significantly more likely to exhibit externalizing problems. It also is possible that genes that confer risk for aggression may interact with genes that confer risk for negative emotionality, similar to studies that have demonstrated overlapping genetic influences between negative emotionality and more generalized externalizing behavior (Mikolajewski et al. 2013; Rhee et al. 2015).

A similar pattern emerged in the interaction between negative emotionality and family income at age 5. Although much research has examined the relationship between negative emotionality (Eisenberg et al. 2000) and related constructs (e.g., negative affectivity; Wang et al. 2020) on externalizing behaviors, income in conjunction with negative emotionality has received far less attention. Our results showed that negative emotionality was related to externalizing problems in both low-income and high-income families. However, the slope was greater for children from low-income homes; consequently, income disparities may differentially impact children as a function of temperament.

Effects of birth complications on externalizing behavior

At age 5, birth complications were not significantly related to externalizing problems after negative emotionality was added to the model. It was expected that certain birth complications would lead to changes in neural development that engender externalizing problems in young children (Jones et al. 2019). Given our results, it is possible that negative emotionality has a mediating effect, causing the relationship between birth complications and externalizing to be indirect. Future research should explore this. Given that nearly any child can experience birth complications regardless of family factors or genetic risk, the reduction of birth complications through medical and other interventions may be important for prevention of externalizing problems, particularly in early childhood.

By middle childhood, birth complications were only predictive of externalizing behaviors for children from higher income families; for these children, having more birth complications resulted in higher externalizing scores, highlighting the harmful effect that adverse perinatal conditions can have in an environment that is relatively resource plentiful. Children from lower income families had high risk for externalizing scores regardless of their birth complication history, which underscores the risk that economic hardship poses for behavioral development. This is consistent with the effects of birth complications on cognitive development (Linsell et al. 2015) and with other research showing that birth complications have impacts on externalizing behaviors via their interactions with other moderators such as IQ and psychosocial diversity (Liu et al. 2009).

Summary of findings

Our results show that 5-year-old externalizing behaviors were higher for boys, children with high negative emotionality, children who experience insensitive parenting at age 4, and children from lower income homes. By middle childhood, the only significant effects beyond the stability from age 5 were interactive effects. These results suggest that a complicated pattern of health problems, genetic factors, temperament traits, and familial risk factors contribute to externalizing problems in early and middle childhood. The pattern of interactions that we saw of birth complications or negative emotionality having an effect only in the absence of a moderating risk factor may be more similar to a bioecological model than to a diathesis-stress model; a similar pattern has been shown for aggressive play in preschoolers (DiLalla et al. 2009). These factors appear to change across the transition from early to middle childhood, which further complicates the search for predictors of externalizing behavior. A developmental approach to externalizing behavior is warranted in order to understand the factors that continuously predict stability and change in externalizing behavior across the lifespan (Kjeldsen et al. 2021).

The complexity of these interactions as well as the developmental changes that affect stability and change in externalizing behaviors across ages highlight the “gloomy prospect” outlined by Briley et al. (2019), suggesting that a generalizable model may be difficult or impossible to attain. One reason that genetic effects have been difficult to find and replicate is that these effects differ across developmental and environmental contexts. Our results suggest that genetic studies that incorporate developmental and environmental contexts are critical for exposing genetic effects. These may be key to uncovering genes using Genome Wide Association (GWA) methods. Replication failures in GWA studies (e.g., Barr et al. 2020) may be partly due to developmental and environmental contexts that are not explored using typical genome-wide methods (Salvatore et al. 2015). Accounting for this complexity will likely lead to increased understanding of the genes involved in externalizing behavior as well as the pathways through which they impact externalizing behavior. Additional care taken in defining phenotypes as well as research questions will be essential for clarifying models of externalizing behaviors (Briley et al. 2019).

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This study has several strengths. The utilization of twins and triplets in the sample allowed for an examination of gene-environment interaction using a genetic risk index. It also allowed examination of multiple children within a family using multilevel modeling, simultaneously modeling within and between family variance. The study also used longitudinal data, providing information both on how variables predict future outcomes and on how the effects of different variables change throughout early development. This was a multi-trait, multi-method study, including parent questionnaires and behavioral coding; these differing forms of data collection decrease the threat of reporter bias, strengthening the results. Finally, the sample is a relatively rural one, including families from a wide range of incomes and education levels, providing some SES diversity.

One limitation of this study is that, given the relatively small sample size, the study is underpowered for detecting small effect sizes. Another limitation is that the sample was lacking in racial and ethnic diversity; participating families were primarily Caucasian. Additionally, although a major study strength, the use of a twin design may be a limitation, given that the experience of having multiples may differ from other familial dynamics. However, parenting styles of twins have recently been shown to be comparable to those of non-twin siblings (Monkediek et al. 2020).

Future research should further examine the genetic risk for negative emotionality to expand upon our results showing that for children at low genetic risk for aggression, negative emotionality was significantly related to externalizing problems. Because temperament is influenced by genetic factors, it is possible that genes that confer risk for aggression may interact with genes that confer risk for negative emotionality; this possible interaction should be explored. Finally, interventions aimed at increasing access to prenatal healthcare and efforts made to minimize the income gap may have important downstream effects, including the reduction of externalizing problems in children, although direct intervention studies are needed to empirically test this. Relatedly, it will be important to conduct similar investigations across various cultural contexts in order to examine the roles of birth complications and income in different ethnic and cultural groups.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated interactions among biological, genetic, and ecological variables that predicted externalizing behaviors in early and middle childhood. Specifically, children at high risk from a genetic risk for aggression or from low income were likely to have high scores on externalizing, but for children not at high risk, those with increased birth complications or more negative emotionality were at risk for high scores on externalizing. Although externalizing behaviors are fairly stable, future studies must consider the complexity of the interactions between and among genes and environments as they occur across development.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed for this study are not publicly available but are available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Syntax used for analyses is available upon request from the first author.

References

Aber L, Morris P, Raver C (2012) Children, families and poverty: definitions, trends, emerging science and implications for policy and commentaries. Soc Policy Rep 26(3):1–29

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families. ASEBA, Burlington

Barr PB, Salvatore JE, Wetherill L, Anokhin A, Chan G, Edenberg HJ, Kuperman S, Meyers J, Nurnberger J, Porjesz B, Schuckit M (2020) A family-based genome wide association study of externalizing behaviors. Behav Gen 50(3):175–183

Bates TC, Maes H, Neale MC (2019) umx: Twin and path-based structural equation modeling in R. Twin Res Hum Genet 22(1):27–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2019.2

Bellani M, Nobile M, Blanchi V, van Os J, Brambilla P (2013) Genotype by environment interaction and neurodevelopment III. Focus on the child’s broader social ecology. Epidemiol Psych Sci 22(2):125–129

Bersted KA, DiLalla LF (2016) The influence of DRD4 genotype and perinatal complications on preschoolers’ negative emotionality. J Appl Dev Psychol 42:71–79

Boeldt DL, Rhee SH, DiLalla LF, Mullineaux PY, Schulz-Heik RJ, Corley RP, Young SE, Hewitt JK (2012) The association between positive parenting and externalizing behaviour. Infant Child Dev 21(1):85–106

Bradley RH, Corwyn RF (2002) Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu Rev Psychol 53(1):371–399

Bradley RH, Corwyn RF (2008) Infant temperament, parenting, and externalizing behavior in first grade: a test of the differential susceptibility hypothesis. J Child Psychol Psych 49(2):124–131

Briley DA, Livengood J, Derringer J, Tucker-Drob EM, Fraley RC, Roberts BW (2019) Interpreting behavior genetic models: seven developmental processes to understand. Behav Genet 49:196–210

Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA (2006) The bioecological model of human development. In: Lerner RM, Damon W (eds) Handbook of child psychology: theoretical models of human development. Wiley, New York, pp 793–828

Burt SA, Klump KL (2014) Parent–child conflict as an etiological moderator of childhood conduct problems: an example of a ‘bioecological’ gene–environment interaction. Psych Med 44(5):1065–1076

Carden SW, Holtzman NS, Strube MJ (2017) CAHOST: an Excel workbook for facilitating the Johnson-Neyman technique for two-way interactions in multiple regression. Front Psych 8:1293. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01293

Coe JL, Davies PT, Hentges RF, Sturge-Apple ML (2019) Understanding the nature of associations between family instability, unsupportive parenting, and children’s externalizing symptoms. Dev Psychopathol 32(1):257–269

Cohen J (1968) Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psych Bull 70(4):213–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0026256

Dhamija D, Tuvblad C, Baker LA (2016) Behavioral genetics of the externalizing spectrum. In: Beauchaine TP, Hinshaw SP (eds) The Oxford handbook of externalizing spectrum disorders. Oxford University Press, pp 105–124

DiLalla LF (2002) Behavior genetics of aggression in children: review and future directions. Dev Rev 22:593–622

DiLalla LF, Jamnik MR (2019) The Southern Illinois Twins/Triplets and Siblings Study (SITSS): a longitudinal study of early child development. Twin Res Hum Genet 22(6):779–782

DiLalla LF, Elam KK, Smolen A (2009) Genetic and gene–environment interaction effects on preschoolers’ social behaviors. Dev Psychobiol 51(6):451–464

DiLalla LF, Gheyara S, Bersted K (2013) The Southern Illinois Twins and Siblings Study (SITSS): description and update. Twin Res Hum Genet 16(1):371–375

DiLalla LF, Bersted K, John SG (2015) Evidence of reactive gene-environment correlation in preschoolers’ prosocial play with unfamiliar peers. Dev Psychol 51(10):1464–1475

DiLalla LF, Trask MM, Casher GA, Long SS (2020) Evidence for reliability and validity of parent reports of twin children’s birth information. Early Child Res Q 51:267–274

Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Losoya S, Murphy B, Jones S, Poulin R, Reiser M (2000) Prediction of elementary school children’s externalizing problem behaviors from attentional and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Dev 71(5):1367–1382

Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, Zhou Q, Losoya SH (2009) Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Dev Psychol 45(4):988–1008

Grusec JE (2011) Socialization processes in the family: social and emotional development. Annu Rev Psychol 62:243–269

Hendriks AM, Finkenauer C, Nivard MG, Van Beijsterveldt CEM, Plomin RJ, Boomsma DI, Bartels M (2020) Comparing the genetic architecture of childhood behavioral problems across socioeconomic strata in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Eur Child Adolesc Psy 29(3):353–362

Hicks BM, Foster KT, Iacono WG, McGue M (2013) Genetic and environmental influences on the familial transmission of externalizing disorders in adoptive and twin offspring. JAMA Psychiat 70(10):1076–1083

Hodgins S, Kratzer L, McNeil TF (2001) Obstetric complications, parenting, and risk of criminal behavior. Arch Gen Psychiat 58(8):746–752

Hosokawa R, Katsura T (2018) Socioeconomic status, emotional/behavioral difficulties, and social competence among preschool children in Japan. J Child Fam Stud 27(12):4001–4014

Jaekel J, Pluess M, Belsky J, Wolke D (2015) Effects of maternal sensitivity on low birth weight children’s academic achievement: a test of differential susceptibility versus diathesis stress. J Child Psychol Psyc 56(6):693–701

Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Dodge KA, Rutter M, Taylor A, Tully LA (2005) Nature x nurture: genetic vulnerabilities interact with physical maltreatment to promote conduct problems. Dev Psychopathol 17(1):67–84

Jones SL, Dufoix R, Laplante DP, Elgbeili G, Patel R, Chakravarty MM, King S, Pruessner JC (2019) Larger amygdala volume mediates the association between prenatal maternal stress and higher levels of externalizing behaviors: sex specific effects in Project Ice Storm. Front Hum Neurosci 13:144

Kauten R, Barry CT (2020) Externalizing behavior. In: Zeigler-Hill V, Shackelford TK (eds) Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_894

Kjeldsen A, Nes RB, Sanson A, Ystrom E, Karevold EB (2021) Understanding trajectories of externalizing problems: stability and emergence of risk factors from infancy to middle adolescence. Dev Psychopathol 33(1):264–283

Lansford JE, Malone PS, Tapanya S, Tirado LMU, Zelli A, Alampay LP, Al-Hassan SM, Bacchini D, Bornstein MH, Chang L, Deater-Deckard K, Giunta LD, Dodge KA, Oburu P, Pastorelli C, Skinner AT, Sobring E, Steinberg L (2019) Household income predicts trajectories of child internalizing and externalizing behavior in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. Int J Behav Dev 43(1):74–79

LaPrairie JL, Schechter JC, Robinson BA, Brennan PA (2011) Perinatal risk factors in the development of aggression and violence. Adv Genet 75:215–253

Letourneau NL, Duffett-Leger L, Levac L, Watson B, Young-Morris C (2013) Socioeconomic status and child development: a meta-analysis. J Emot Behav Disord 21(3):211–224

Linsell L, Malouf R, Morris J, Kurinczuk JJ, Marlow N (2015) Prognostic factors for poor cognitive development in children born very preterm or with very low birth weight: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr 169(12):1162–1172

Liu J (2004) Childhood externalizing behavior: theory and implications. J Child Adol Psychiatr Nurs 17(3):93–103

Liu J (2011) Early health risk factors for violence: conceptualization, evidence, and implications. Aggress Violent Beh 16(1):63–73

Liu J, Raine A, Wuerker A, Venables PH, Mednick S (2009) The association of birth complications and externalizing behavior in early adolescents: direct and mediating effects. J Res Adolesc 19(1):93–111

Marceau K, Rolan E, Leve LD, Ganiban JM, Reiss D, Shaw DS, Natsuaki M, Egger H, Neiderhiser JM (2019) Parenting and prenatal risk as moderators of genetic influences on conduct problems during middle childhood. Dev Psychol 55(6):1164–1181

McDevitt SC, Carey WB (1978) The measurement of temperament in 3–7 year old children. J Child Psychol Psychiat 19:245–253

McGue M, Bouchard TJ (1984) Adjustment of twin data for the effects of age and sex. Behav Genet 14:325–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01080045

Mikolajewski AJ, Allan NP, Hart SA, Lonigan CJ, Taylor J (2013) Negative affect shares genetic and environmental influences with symptoms of childhood internalizing and externalizing disorders. J Abnorm Child Psych 41(3):411–423

Miller P, Votruba-Drzal E (2017) The role of family income dynamics in predicting trajectories of internalizing and externalizing problems. J Abnorm Child Psych 45(3):543–556

Monkediek B, Schulz W, Eichhorn H, Diewald M (2020) Is there something special about twin families? A comparison of parenting styles in twin and non-twin families. Soc Sci Res 90:102441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102441

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (2005) Duration and developmental timing of poverty and children’s cognitive and social development from birth through third grade. Child Dev 76(4):795–810

Nichols RC, Bilbro WC (1966) The diagnosis of twin zygosity. Acta Genet Stat Med 16:265–275

Nobile M, Giorda R, Marino C, Carlet O, Pastore V, Vanzin L, Bellina M, Molteni M, Battaglia M (2007) Socioeconomic status mediates the genetic contribution of the dopamine receptor D4 and serotonin transporter linked promoter region repeat polymorphisms to externalization in preadolescence. Dev Psychopathol 19(4):1147–1160

Paulussen-Hoogeboom MC, Stams GJJ, Hermanns JM, Peetsma TT (2008) Relations among child negative emotionality, parenting stress, and maternal sensitive responsiveness in early childhood. Parent-Sci Pract 8(1):1–16

Peverill M, Dirks MA, Narvaja T, Herts KL, Comer JS, McLaughlin KA (2021) Socioeconomic status and child psychopathology in the United States: a meta-analysis of population-based studies. Clin Psychol Rev 83:101933

Pike A, Reiss D, Hetherington EM, Plomin R (1996) Using MZ differences in the search for nonshared environmental effects. J Child Psych and Psych 37(6):695–704

Pinquart M (2017) Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: an updated meta-analysis. Dev Psychol 53(5):873

Rhee SH, Lahey BB, Waldman ID (2015) Comorbidity among dimensions of childhood psychopathology: converging evidence from behavior genetics. Child Dev Perspect 9(1):26–31

Salvatore JE, Aliev F, Bucholz K, Agrawal A, Hesselbrock V, Hesselbrock M, Bauer L, Kuperman S, Schuckit MA, Kramer JR, Edenberg HJ (2015) Polygenic risk for externalizing disorders: gene-by-development and gene-by-environment effects in adolescents and young adults. Clinical Psychol Sci 3(2):189–201

Shiner RL, Buss KA, McClowry SG, Putnam SP, Saudino KJ, Zentner M (2012) What is temperament now? Assessing progress in temperament research on the twenty-fifth anniversary of Goldsmith et al. (1987). Child Dev 6:436–444

Singh AL, Waldman ID (2010) The etiology of associations between negative emotionality and childhood externalizing disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 119(2):376–388

Toscano C, Soares I, Mesman J (2020) Controlling parenting behaviors in parents of children born preterm: a meta-analysis. J Dev Behav Pediatr 41(3):230–241

van der Valk JC, van den Oord EJCG, Verhulst FC, Boomsma DI (2003) Genetic and environmental contributions to stability and change in children’s internalizing and externalizing problems. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry 42:1212–1220

Waller R, Hyde LW, Klump KL, Burt SA (2018) Parenting is an environmental predictor of callous-unemotional traits and aggression: a monozygotic twin differences study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 57(12):955–963

Wang F, Christ SL, Mills-Koonce WR, Garrett-Peters P, Cox MJ (2013) Association between maternal sensitivity and externalizing behavior from preschool to preadolescence. J Appl Dev Psychol 34(2):89–100

Wang FL, Galán CA, Lemery-Chalfant K, Wilson MN, Shaw DS (2020) Evidence for two genetically distinct pathways to co-occurring internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence characterized by negative affectivity or behavioral inhibition. J Abnorm Psychol 129(6):633–645

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from Southern Illinois University School of Medicine Research Special Grants, from the SIU Center for Integrative Research-Cognitive Neuro Sciences (CIR-CNS), and from the Central Research Committee of Southern Illinois University to the first author. We gratefully thank the SITSS families for their years of participation and many research assistants for help with data collection. We also gratefully thank our reviewers for their careful and thoughtful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by Lisabeth DiLalla, Matthew Jamnik, and Riley Marshall. Analyses were performed by Lisabeth DiLalla. All authors contributed to the first draft of the manuscript and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Lisabeth Fisher DiLalla, Matthew R. Jamnik, Riley L. Marshall, Rachel Weisbecker, and Cheyenne Vazquezdeclare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

Studies were approved by the Southern Illinois University Institutional Review Board prior to any data collection.

Ethical approval

All research protocols were approved by the Southern Illinois University Institutional Review Board or the SIU School of Medicine Springfield Committee for Research Involving Human Subjects.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all parents prior to beginning testing.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DiLalla, L.F., Jamnik, M.R., Marshall, R.L. et al. Birth Complications and Negative Emotionality Predict Externalizing Behaviors in Young Twins: Moderations with Genetic and Family Risk Factors. Behav Genet 51, 463–475 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-021-10062-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-021-10062-y