Abstract

Prior work has demonstrated that religious beliefs and moral attitudes are often related to sexual functioning. The present work sought to examine another possibility: Do sexual attitudes and behaviors have a relationship with religious and spiritual functioning? More specifically, do pornography use and perceived addiction to Internet pornography predict the experience of religious and spiritual struggle? It was expected that feelings of perceived addiction to Internet pornography would indeed predict such struggles, both cross-sectionally and over time, but that actual pornography use would not. To test these ideas, two studies were conducted using a sample of undergraduate students (N = 1519) and a sample of adult Internet users in the U.S. (N = 713). Cross-sectional analyses in both samples found that elements of perceived addiction were related to the experience of religious and spiritual struggle. Additionally, longitudinal analyses over a 1-year time span with a subset of undergraduates (N = 156) and a subset of adult web users (N = 366) revealed that perceived addiction to Internet pornography predicted unique variance in struggle over time, even when baseline levels of struggle and other related variables were held constant. Collectively, these findings identify perceived addiction to Internet pornography as a reliable predictor of religious and spiritual struggle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Many Americans view pornography on a regular basis (Wright, 2013a, 2013b; Wright, Bae, & Funk, 2013), and some estimates place pornography use as 13 % of total Internet traffic (Ogas & Gaddam, 2011). Despite this popularity, Internet pornography use is a highly controversial topic. Researchers (e.g., Fisher & Barak, 2001), clinicians (e.g., Bergner & Bridges, 2002), and clergy (e.g., Anderson, 2007) have debated the merits of such use. Within academic circles, the central points of focus tend to be on the potential psychosocial benefits and costs of pornography use (e.g., Hald & Malamuth, 2008; Malamuth, Hald, & Koss, 2012). In popular media, by contrast, these debates often have a moral, if not openly religious, component to them (e.g., Stoeker & Arterburn, 2009). Popular religious books and magazines often expound upon the purportedly dangerously addictive nature of pornography use, the moral decline resultant from pornography use, and the negative effects of pornography use on religious and spiritual well-being (e.g., Driscoll, 2009).

Despite the focus of religious communities on the dangers of Internet pornography, there has been little research on the relationships between pornography use and religious and spiritual functioning. If pornography use actually is a threat to religious and spiritual well-being, this would be of obvious interest to religious professionals, but it may also be of concern to experts in the medical and mental health communities. Religious and spiritual well-being is a known predictor of positive mental and physical health outcomes over time (Pargament, Koenig, Tarakeshwar, & Hahn, 2004). Conversely, indicators of religious and spiritual distress are known predictors of negative physical, mental, emotional, and social outcomes, both concurrently and over time (for a review, see Exline, 2013). As such, the possibility of an association between pornography use and diminished religious and spiritual well-being should be of interest to a variety of professional communities concerned about health and well-being. To this end, the present studies were designed to examine the associations between pornography use and religious and spiritual struggle, to determine if these associations are related to pornography use itself or to feelings of perceived addiction, and to establish whether pornography use and related variables may be related to the experience of religious and spiritual struggles over time.

Internet Pornography Use and Perceived Addiction

With the rise in Internet use in the late 1990s and early 2000s, increasing academic attention was paid to the possibility of using the Internet for sexual purposes (e.g., Cooper, 1998). Much of this early attention was negative in nature, often citing the potential for users of online sexual media to become compulsive or addicted (Griffiths, 2000b). In subsequent years, many theoretical inquiries examined various aspects of addiction to Internet pornography (Young, 2008) and many case studies (e.g., Bostwick & Bucci, 2008; Griffiths, 2000a) documented individual examples of compulsive pornography consumption. Qualitative works (Cavaglion, 2008, 2009) and many self-report studies (Cooper, Delmonico, & Burg, 2000; Grubbs, Sessoms, Wheeler, & Volk, 2010) have found that many people think of themselves as pornography addicts.

Despite the body of research regarding pornography use, there is no consensus regarding the addictive nature of Internet pornography. Hypersexuality, considered for inclusion in the DSM-5, would have subsumed the notion of pornography addiction. However, the diagnosis was not included for a variety of reasons (Piquet-Pessôa, Ferreira, Melca, & Fontenelle, 2014; Steele, Staley, Fong, & Prause, 2013; Sungur & Gündüz, 2014). Additionally, many studies have cast doubt on the construct of pornography addiction in general, citing a lack of empirical evidence for the construct and the absence of a scientific consensus around its definition (for a review, see Ley, Prause, & Finn, 2014). As such, there is a notable trend in which individuals identify as having an addiction that is not officially recognized by any diagnostic standard. More simply, a number of pornography users seem to be experiencing a perceived addiction to sexual media (Grubbs, Exline, Pargament, Hook, & Carlisle, 2015a), even in the absence of an official diagnosis.

Perceived addiction to Internet pornography attempts to define the propensity of individuals to label themselves as addicted to pornography (Grubbs, Volk, Exline, & Pargament, 2015c). Although novel in regards to pornography use, perceived addiction has been studied regarding substance use for decades (e.g., Eiser, Van der Pligt, Raw, & Sutton, 1985; Okoli, Richardson, Ratner, & Johnson, 2009). Although self-perceived addiction is distinct from actual addictive behavioral patterns, the two often overlap substantially, and perceived addiction does predict greater addictive behavior over time (Okoli et al., 2009). Furthermore, a number of measures of pornography addiction and hypersexuality fully rely on individuals’ self-reported perceptions of their sexual behaviors, rather than any objective measurement of behavior (for reviews, see Hook, Hook, Davis, Worthington, & Penberthy, 2010; Wéry & Billieux, 2015; Womack, Hook, Ramos, Davis, & Penberthy, 2013). As such, much of the research related to hypersexual behavior and pornography addiction may actually be studying perceived addiction rather than an actual addiction or dependence. Even so, perceived addiction is likely a concern to health professionals, as perceptions of addiction to pornography have been linked to anxiety (Grubbs et al., 2015c), neuroticism (Egan & Parmar, 2013), hopelessness (Cavaglion, 2009), and general psychological distress over time (Grubbs, Stauner, Exline, Pargament, & Lindberg, 2015b). As such, understanding the factors related to perceived addiction is of importance. One such factor is religious belief.

Religion/Spirituality and Internet Pornography Use

When compared to the non-religious, religious people tend to have more conservative sexual values (Ahrold, Farmer, Trapnell, & Meston, 2011), tend to disapprove of pornography use (Grubbs et al., 2015a; Thomas, 2013), and are less likely to use pornography (Wright, 2013b). Yet, religious individuals do use pornography with some frequency (Edelman, 2009; MacInnis & Hodson, 2014). This use does not, however, appear to be without consequence. In comparison to religious individuals who do not use pornography, religious users of pornography report less happiness in life (Nelson, Padilla-Walker, & Carroll, 2010; Patterson & Price, 2012) and often report substantial guilt and shame over their use (Grubbs et al., 2010). Finally, religious individuals are much more likely to report feelings of perceived addiction to Internet pornography than their non-religious counterparts (Abell, Steenbergh, & Boivin, 2006; Grubbs et al., 2015a). This is likely due to the fact that religious individuals often find internet pornography use to be a violation of their personal sexual values or morals (Grubbs et al., 2015a), leading to profound dissonance between sexual values and sexual behaviors, a known risk factor for feelings of addiction to pornography or sexual behaviors (Hook et al., 2015).

This link between religious belief and perceived addiction is also evident within popular literature about pornography “addiction.” In 2014, a search of the term “pornography addiction” on the online book retail website, Amazon.com, revealed over 1900 results, with over 900 being in the “Religion and Spirituality” section of the bookstore (Grubbs, Exline, & Pargament, 2014). Notably, a number of these books are explicitly focused on the idea of pornography addiction—often emphasizing the way that such an addiction negatively impacts one’s religious and spiritual life (e.g., Driscoll, 2009; Tiede, 2012). More simply, much popular religious literature suggests that pornography use and associated addiction is a source of religious and spiritual struggle.

Religious and Spiritual Struggle

A growing body of research has documented the ability of religious and spiritual beliefs and practices to generate difficulty and conflicts in the spiritual domain, often referred to as religious and spiritual struggles (Exline, Pargament, Grubbs, & Yali, 2014). Recent research has shown that religious and spiritual struggles are common experiences that predict many indicators of poor mental and physical well-being (for a review, see Exline, 2013), such as anxiety and depression (Exline et al., 2014), suicidal tendencies (Rosmarin, Bigda-Peyton, Öngur, Pargament, & Björgvinsson, 2013), poor recovery from illness (Pargament, Koenig, Tarakeshwar, & Hahn, 2001; Pargament et al., 2004), and poor coping in the wake of trauma (Pirutinsky, Rosmarin, Pargament, & Miclarsky, 2011). Exline et al. described several domains of religious and spiritual struggle that can be readily assessed. Below, we describe three types of religious and spiritual struggle that may be particularly related to Internet pornography use and perceived addiction: divine struggles, moral struggles, and interpersonal struggles.

Divine Struggles

Divine struggles are those that people experience in relation to their conception of deity (Exline, 2013). These struggles may involve anger or disappointment toward God (Exline, Park, Smyth, & Carey, 2011), feelings of conflict with deity (Kane, Cheston, & Greer, 1993), seeing God as cruel or distant (Exline, Grubbs, & Homolka, 2015), or feelings of betrayal or punishment by God (Murray-Swank & Pargament, 2005).

Many popular religious books on pornography addiction note that a fractured relationship with deity is a likely result of pornography use and addiction (Driscoll, 2009; Stoeker & Arterburn, 2009; Tiede, 2012). Such claims are consistent with empirical work showing that individuals might experience divine struggles in the wake of a moral transgression they themselves committed (Grubbs & Exline, 2014). As such, we might expect to find that perceived addiction to internet pornography and pornography use are salient predictors of such struggles, particularly given that many religious individuals view pornography use as a transgression (Grubbs et al., 2015a).

Moral Struggles

Moral struggles involve perceived conflict between one’s behavior and core spiritual values. These struggles center around tensions between spiritual principles and actions, such as concern about violating moral principles, excessive guilt about perceived wrongdoing, or feeling torn between what is right versus wrong (Exline, 2013). Given the morally charged nature of pornography use for many religious individuals (e.g., Grubbs et al., 2015a; Thomas, 2013), it is not surprising to find that many popular religious books decry the consequences of pornography use (Driscoll, 2009; Stoeker & Arterburn, 2009; Wilson, 2007). Furthermore, since moral emotions are often a key part of self-perceived sexual addiction (Gilliland, South, Carpenter, & Hardy, 2011) and are known contributors to perceived addiction to pornography (Grubbs et al., 2015a), it is reasonable to assume that there may be a link between moral religious and spiritual struggles and perceived addiction to Internet pornography.

Interpersonal Struggles

Interpersonal religious and spiritual struggles often involve conflicts with others about religious and spiritual issues (Exline et al., 2014). These struggles are also described as a potential consequence of pornography use by a number of popular (although not empirical) works (Stoeker & Arterburn, 2009; Wilson, 2007). Despite these supposed links, no prior work has systematically examined associations between pornography use, perceived addiction, and interpersonal religious and spiritual struggles. Similarly, there is limited evidence to suggest that Internet pornography use is inherently dangerous to interpersonal well-being or social relationships (Ley et al., 2014), although there is much evidence suggesting that pornography consumption can be associated with more open sexual values (e.g., Wright, 2013b), greater propensities toward infidelity (Wright, Tokunaga, & Bae, 2014), and potentially concerning outcomes such as objectification of women (Peter & Valkenberg, 2009a) and diminished sexual satisfaction with partners (Peter & Valkenberg, 2009b). In short, the links between pornography use and interpersonal outcomes are somewhat mixed. As such, we sought to test the claims of popular religious writings warning of such associations. However, given the lack of empirical work in the area, we did not make the prediction that there would be a link between pornography use or perceived addiction and interpersonal religious and spiritual struggles.

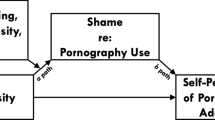

Building on the aforementioned notions, the present work sought to examine the relationships between pornography use, perceived addiction, and spiritual struggle. Similar to prior work (e.g., Grubbs et al., 2015a; Hook et al., 2015), we conceptualized perceived addiction as being related to religious or moral scruples around pornography use. In short, pornography use often leads religious individuals to experience dissonance between their values and their behaviors. Perceived addiction, then, is a logical result of this dissonance. It is also an indicator of the profound distress that certain individuals may feel as a result of pornography use. A logical consequence of this dissonance and distress would be religious and spiritual struggles. Although pornography use may predict religious and spiritual struggles, it seems that this association would most likely flow from perceived addiction, rather than from the use itself. Ultimately, we expected to find that individuals’ attitudes toward their own use would emerge as predictors of religious and spiritual struggle. From these conceptions then, the following hypotheses were formulated:

H1

Perceived addiction to Internet pornography will be related to the experience of specific religious and spiritual struggles (Divine, Interpersonal, and Moral).

H2

The relationships between perceived addiction and religious and spiritual struggle will be evident over a one-year time frame, even when controlling for baseline religious and spiritual struggle.

H3

Any association between actual levels of pornography use and religious and spiritual struggle will be accounted for by perceived addiction.

Study 1

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were undergraduate students in introductory psychology courses at three universities in the U.S.: a mid-sized private university in the Midwest, a large public university in the Midwest, and a mid-sized religiously affiliated university in the Southwest. Participants were offered partial course credit for completing a survey entitled “Religious and Spiritual Issues in College Life” that examined a variety of beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes. Data were collected over the course of 6 semesters.

Only those who reported viewing pornography within the past 6 months were included in analyses (T1; n = 1519; 67.2 % men, 32.5 % women, 0.2 % other; M age = 19.3, SD = 1.3). Ethnicities included White/Caucasian (71 %), Asian/Pacific Islander (15 %), African-American/Black (10 %), Latino/Hispanic (6 %), Native American/Alaska Native (2 %), Middle Eastern (2 %), and other/prefer not to say (2 %). Religious affiliations included Christian (65 %), no religious affiliation (28 %), Jewish (2 %), other (2 %), Muslim (1 %), and Hindu (1 %).

One year following the initial survey, 355 students from the first four semesters of data collection were contacted regarding a follow-up study (T2) entitled “Religious and Spiritual Issues in College Life: Year 2.” Of those contacted, 156 participated in the follow-up survey (Response rate = 44 %; 63 % men; M interval = 355.5, SD = 22.2). Those who participated in the follow-up survey were compensated with a $20.00 gift card to the online retailer Amazon.com. No systematic differences on any key variables at T1 were observed between those who did participate in the follow-up versus those who did not.

Measures

Unless otherwise indicated, all measures were scored by taking the average across items. Descriptive statistics for all included measures are shown in Table 1.

Pornography Variables

At T1, actual pornography use was assessed by a single item asking users to indicate how many hours, on average, they spent per day viewing pornography. Consistent with previous research regarding this topic, responses were on a scale of 0–12 h in increments of .1 (Bradley, Grubbs, Uzdavines, Exline, & Pargament, 2016; Grubbs et al., 2015a, b, c; Wilt, Cooper, Grubbs, Exline, & Pargament, 2016).

To assess perceived addiction to Internet pornography, the Cyber Pornography Use Inventory-9 (CPUI-9) was administered (Grubbs et al., 2015c). This inventory measures the aspects of perceived addiction to Internet pornography on three 3-item subscales: Perceived Compulsivity (“Even when I do not want to view pornography, I feel drawn to it”), Access Efforts (“At times, I rearrange my schedule in order to be alone to view pornography”), and Emotional Distress (“I feel depressed after viewing pornography”). Participants rate their agreement with each item on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). The scale may be used either as a total score reflecting the average of all 9 items, or as three facet scores reflecting the averages of the three 3-item subscales. For the present work, the total score was used.

Religious and Spiritual Struggles

At T1 and T2, three subscales of the Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale (RSS) (Exline et al., 2014) were administered. The three subscales were the 5-item Divine Struggles subscale (e.g., “felt angry at God”), the 4-item Interpersonal subscale (e.g., “had conflicts with other people about religious/spiritual matters”), and the 4-item Moral subscale (e.g., “felt guilty for not living up to my moral standards”). At both T1 and T2, participants rated their agreement with the aforementioned items in response to the prompt “Over the past few months, to what extent have you had each of the experiences listed below?” Participants responded on a scale of 1 (not at all/does not apply) to 5 (a great deal).

Personality Variables

The Neuroticism subscale of the Big Five Inventory-44 (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991) was included as a control variable, as prior work has linked it to both perceived addiction to internet pornography (e.g., Egan & Parmar, 2013) and religious and spiritual struggle (Ano & Pargament, 2013). This 8-item scale requires participants to rate their agreement with items such as “I can be tense,” on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

The 13-item version of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Reynolds, 1982) was also included, as previous work has suggested that socially desirable response styles may impact willingness to report both pornography use and religious and spiritual struggle (e.g., Exline et al., 2011; Grubbs et al., 2015c). Participants respond to 13 statements (e.g., “Sometimes, it is hard for me to go on with my work if I am not encouraged” and “I am always courteous, even to people who are disagreeable”) with an answer of either “True” or “False.” Socially desirable responses are assigned a value of 1. Responses were summed.

Results

Descriptive statistics for all included variables are shown in Table 1.

Time 1 Analyses

Correlational Analyses

Pearson correlations were conducted for all included variables (Table 2). Consistent with the hypotheses, perceived addiction was positively associated with the three religious and spiritual struggles. Similarly, small correlations were observed between daily pornography use and both divine and interpersonal struggles. We also noted that neuroticism, although related to the included religious and spiritual struggle measures, was largely unrelated to perceived addiction.

Hierarchical regressions were conducted for each of the included religious and spiritual struggle variables (three total regressions). In the first step of each regression, neuroticism, socially desirable responding, gender (dummy coded, male = 1; women/other = 0),Footnote 1 and average pornography use were entered. Subsequently, perceived addiction was entered (see Table 3).

For divine struggles, the first step with control variables accounted for 6 % of the variance. When perceived addiction was entered as a predictor in the subsequent step, it accounted for an additional 7 % of unique variance. Using the Rmediation package (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011) for R statistical software (R Development Core Team, 2015), we also tested for the potential of an indirect effect of daily pornography use on divine struggle. Using distribution of the product confidence limits for indirect effects (PRODCLIN) (Mackinnon, Fritz, Williams, Lockwood, & 2007), pornography use was found to have small indirect effect on divine struggle (Indirect Effect = .033, 95 % CI [.025, .043]).

For interpersonal struggles, the first step accounted for 4.9 % of total variance in the struggle. When perceived addiction was entered as a predictor in the subsequent step, it accounted for an additional 4.7 % of unique variance. In both steps of this regression, pornography use in hours was also a significant predictor of interpersonal struggle. Contrary to hypotheses, there was no evidence to suggest that perceived addiction fully mediated this relationship. Using distribution of the product confidence limits for indirect effects, pornography use was found to have small indirect effect on interpersonal struggle (Indirect Effect = .029, 95 % CI [.020, .038]).

For moral struggles, the first step accounted for 3 % of total variance. When perceived addiction was entered as a predictor in the subsequent step, it accounted for an additional 16 % of unique variance. Notably, when perceived addiction was entered into the regression, daily pornography use in hours emerged as an inverse predictor of moral struggles. Using PRODCLIN, pornography use was found to have small indirect effect on moral struggle through perceived addiction (Indirect Effect = .067, 95 % CI [.052, .084]).

In sum, across cross-sectional analyses, perceived addiction to internet pornography emerged as a consistent predictor of various religious and spiritual struggles. By contrast, pornography use itself was not directly related to all religious and spiritual struggles, instead demonstrating a positive relationship with interpersonal struggles alone and demonstrating an inverse direct relationship with moral struggles and a positive indirect relationship with moral struggles.Footnote 2 Even so, in each case, pornography use did maintain small indirect effects on struggle through perceived addiction.

Time 2 (1-year Interval) Analyses

To examine our hypotheses over a one-year time frame, we conducted Pearson correlations between T1 measures of pornography use, personality, religious and spiritual struggle, and T2 measures of religious and spiritual struggle (see Table 4). Results revealed moderate correlations between perceived addiction and all three religious and spiritual struggle measures at T2. Actual levels of pornography use at T1 had no significant relationship with religious and spiritual struggles at T2. Additionally, religious and spiritual struggle at T1 displayed rather strong associations with religious and spiritual struggle at T2, pointing to the stability of struggle over time.

Hierarchical regressions were conducted for each T2 struggle (three analyses in total). In the first step of the regression, T1 religious and spiritual struggles, gender, and pornography use at T1 were introduced to account for the role of baseline struggle in predicting T2 struggle. The introduction of these variables into the analysis makes this test extremely conservative, as there is a high degree of overlap between struggle at T1 and T2 (Table 4). In the second step, perceived addiction was introduced. These results are shown in Table 5.

For divine struggle, the first step including all control variables accounted for 37 % of the variance in struggle over time. In the subsequent step, perceived addiction did not emerge as a significant predictor. Given that there was no significant relationship between perceived addiction and divine struggles at T2, no tests of indirect effects were conducted.

For interpersonal struggles, the first step accounted for 41.4 % of variance in struggle over time. In the subsequent step, perceived addiction accounted for an additional 1.6 % of unique variance over time, above and beyond the role of baseline struggle, pornography use at T1, and other relevant control variables. This finding suggests that there was a unique, although modest-sized, relationship between perceived addiction and interpersonal struggles over time. Using PRODCLIN, we also tested for the possibility of an indirect effect of pornography use on struggle over time through perceived addiction, but found that the confidence interval for such an effect included 0 (indirect effect = .015, 95 % CI [−.025, .037]), indicating that there was not a significant indirect effect of use on interpersonal struggles.

For moral struggles, the first step accounted for 39.5 % of variance in struggle over time. In the subsequent step, perceived addiction accounted for an additional 4.4 % of unique variance over time, above and beyond the role of baseline struggle, pornography use at T1, and other relevant control variables. This finding strongly suggests that there is a unique relationship between perceived addiction and moral struggles over time. Using PRODCLIN, we also tested for the possibility of an indirect effect of pornography use on struggle over time through perceived addiction, but found that the confidence interval for such an effect included 0 (indirect effect = .014, 95 % CI [−.034, .022]), indicating that there was not a significant indirect effect of use on moral struggles.

In summary, cross-sectional results of Study 1 collectively supported the notion that perceived addiction to pornography was associated with religious and spiritual struggles. Simple correlations revealed associations between perceived addiction and divine, interpersonal, and moral religious and spiritual struggles. Pornography use itself was mildly, positively associated with both divine and interpersonal religious and spiritual struggles, but these associations were reduced to non-significance when the perceived addiction was introduced into the analyses. Pornography use also displayed a small but significant indirect effect on struggle through perceived addiction for all three struggles. Longitudinal analyses also provided preliminary support for our hypotheses. Hierarchical regressions revealed that for both interpersonal and moral struggles, perceived addiction at T1 was uniquely related to struggle at T2, 1 year later, even when T1 struggles, gender, pornography use, neuroticism, and social desirability were controlled. Pornography use displayed no significant indirect effects through perceived addiction for any struggle over time.

Study 2

To replicate and extend the findings of Study 1, we conducted a second study using identical measures in a community sample of web-using adults in the U.S.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were adult Internet users in the U.S., recruited through Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk Online Workforce Database (mTurk). Prior work has demonstrated that mTurk is suitable for a range of social science research (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011), including mental health and clinical applications (Shapiro, Chandler, & Mueller, 2013). An advertisement was placed on the mTurk website offering participants $3.00 for completing a survey entitled “Personality, Beliefs, and Behavior—Part 1.”

Given the focus of the present study, only those who acknowledged viewing pornography in the past year were included in analyses (N = 713; 338 women, 370 men, 5 other/prefer not to say; M age = 30.2, SD = 9.9). Ethnicities were as follows: Caucasian/White (78 %), African-American/Black (10 %), Latino/Hispanic (7 %), Asian/Pacific Islander (6 %), Native American/Alaska Native (4 %), Middle Eastern (1 %), and other/prefer not to say (1 %). The largest religious affiliation reported was Christian (46 %), with many participants also reporting no religious affiliation (45 %). Other affiliations included Jewish (2 %), Buddhist (2 %), Hindu (1 %), Muslim (1 %), and other (4 %).

One year after the initial survey, 672 participants included in analyses at T1 were contacted regarding participating in a second follow-up survey entitled “Personality, Beliefs, and Behavior–Part 2.” Of the 672 contacted, 366 (52 % men; 54 % response rate, M interval = 363.3 days, SD = 5.0) completed the second survey. Participants who completed the second survey were compensated $3.00. No systematic differences on any key variables at T1 were observed between those who participated in the follow-up versus those who did not.

Results

Time 1 Analyses

Consistent with the analytic strategy employed in Study 1, we initially tested our hypotheses using simple correlational analyses. The results of these analyses are shown below the diagonal in Table 2. Small-to-moderate correlations were observed between all pornography-related variables and both divine and moral struggles. Very small positive associations were also observed between interpersonal struggles perceived addiction. In general, these associations were consistent with Study 1.

Next, we conducted hierarchical regressions paralleling those from Study 1. For divine struggles, the first step with all control variables accounted for 6.8 % of the variance in divine struggle. When perceived addiction was entered into the subsequent step of the regression, it emerged as a unique predictor of divine struggle, accounting for an additional 4.1 % of variance, and in the second step, daily use of pornography did not remain a significant predictor of divine struggle. Using PRODCLIN, pornography use was found to have small indirect effect on divine struggle through perceived addiction (Indirect Effect = .022, 95 % CI [.011, .034]).

For interpersonal struggles, both neuroticism and daily use of pornography emerged as significant predictors of interpersonal struggle, accounting for 6.7 % of the variance. In the subsequent step, perceived addiction also emerged as a significant predictor of interpersonal struggle, accounting for an additional 0.5 % of unique variance. As in Study 1, pornography use again remained a significant predictor of interpersonal struggle. Using PRODCLIN, pornography use was found to have small indirect effect on interpersonal struggle through perceived addiction (Indirect Effect = .009, 95 % CI [.000, .020]).

Finally, for moral struggles, all control variables (neuroticism, social desirability, gender, and pornography use) emerged as significant predictors in the first step of the model, with the first step accounting for 9.8 % of the total variance in the struggle. In the subsequent step, perceived addiction emerged as a significant predictor of moral struggle, accounting for an additional 9.9 % of unique variance. Notably, in the second step of the model, pornography use and gender did not remain significant predictors of moral struggle. Using PRODCLIN, pornography use was found to have small indirect effect on interpersonal struggle through perceived addiction (Indirect Effect = .045, 95 % CI [.019, .073]).

Time 2 (1-year Interval) Analyses

Correlational analyses for simple main effects of T1 pornography variables on T2 (1 year later) struggle variables were computed (Table 6). Positive associations were noted between perceived addiction and all struggles at T2. No significant associations were observed between daily pornography use at T1 and struggles at T2.

As in Study 1, after analyses of simple correlations, hierarchical regressions using the same order as Study 1 were conducted. These results are shown in Table 7. Consistent with Study 1, no pornography-related variables emerged as predictors of divine struggle over time, thereby precluding the possibility of an indirect effect of pornography use on struggle through perceived addiction.

Also consistent with Study 1 results, perceived addiction, but not pornography use, emerged as a significant predictor of interpersonal struggle, accounting for 1.2 % of unique variance in such struggles above and beyond control variables. Using PRODCLIN, we also tested for the possibility of an indirect effect of pornography use on struggle over time through perceived addiction, but found that the confidence interval for such an effect included 0 (indirect effect = .007, 95 % CI [−.002, .018]), indicating that there was no significant indirect effect of use on moral struggles.

Finally, for moral struggles at T2, perceived addiction again emerged as unique predictor of such struggles over time, accounting for 2.2 % of unique variance over time, above and beyond control variables. Collectively, these findings paralleled the findings of Study 1. Using PRODCLIN, we found no significant indirect effect, as the confidence interval for such an effect included 0 (indirect effect = .011, 95 % CI [−.003, .029]).

Discussion

At the outset of the present work, we sought to examine the relationships between pornography use, perceived addiction, and religious and spiritual struggles. Below, we summarize our findings and provide suggestions about future examinations of these topics.

Internet Pornography Use, Perceived Addiction, and Spiritual Struggle

Given the morally—and often religiously—charged nature of pornography use and the debates surrounding it, it is likely that the domains of pornography use and religious functioning are deeply related. Furthermore, given links between perceived addiction and psychological distress and the growing body of literature linking religious and spiritual struggle to psychological distress, illuminating potential relationships between these domains is both theoretically and practically important. Cross-sectional analyses of a large sample of undergraduates and a large sample of adults revealed consistent relationships between perceived addiction and religious and spiritual struggles. All three relevant struggles—divine, interpersonal, and moral—were well predicted by perceived addiction. Although daily pornography use itself was also associated with many facets of religious and spiritual struggle, when perceived addiction was controlled statistically (in regressions), pornography use was only related to the concurrent experience of interpersonal struggle. Perceived addiction displayed consistently positive predictive relationships with religious and spiritual struggle, and pornography use itself displayed small indirect effects on struggle, through perceived addiction. These results persisted in both samples, even when relevant covariates (e.g., neuroticism socially desirable responding, and gender) were controlled.

The present work also represents one of the first examinations of the effects of pornography use and perceived addiction to Internet pornography over time. Over time, in both a general adult sample and an undergraduate sample, we found similar results: Perceived addiction consistently predicted several religious and spiritual struggles in both samples over a 1-year time frame, even when baseline struggles were controlled statistically. Analyses of indirect effects did show that pornography use had a small and indirect effect on struggle through perceived addiction. However, given that these indirect associations were small and accomplished through perceived addiction, our findings strongly suggest that perceived addiction to Internet pornography is the more salient feature of the two variables in predicting the development and maintenance of certain religious and spiritual struggles. Furthermore, given the stability of struggles over time (e.g., correlations of .5 or greater between baseline struggle and struggle 1 year later for all struggles in both studies), the unique relationships between perceived addiction and struggle over time represent a particularly notable finding.

Implications

The present work does establish a link between pornography use and religious and spiritual struggle. However, contrary to the claims made by many religious writings, this relationship appears to have less to do with pornography use itself as it does with perceived addiction. Actual levels of pornography use were relatively unrelated to religious and spiritual struggle, both concurrently and over time (1 year later); however, feelings of addiction to pornography were clearly associated with religious and spiritual struggle, both concurrently and longitudinally. Having said this, it bears mentioning that the presence of perceived addiction was only relevant for individuals who had actually viewed pornography. Individuals who simply do not view pornography are likely to be relatively immune from these specific associations, as perceived addiction implies at least some (even if infrequent) use of pornography. In short, among pornography users, perceived addiction to internet pornography seems to be a better predictor of struggle than the amount of pornography use itself. This represents a notable divergence from research related to more “traditional” addictions, such as substance dependence. Although the perceived process of addiction is a relevant predictor of important outcomes for many addictive disorders, the sheer quantity of the addictive substance consumed and the time spent engaged with the substance are both key features of the addiction. By contrast, this research builds on prior work (Grubbs et al., 2015b) suggesting that the daily engagement in the purportedly addictive behavior (pornography use) may be of secondary importance in predicting salient outcomes, being overshadowed by the psychological perception of addiction.

These links between perceived addiction and struggle are noteworthy, as past research has strongly linked religious morality to perceived addiction (Grubbs et al., 2015a). Perceived addiction seems to largely be a function of religious belief and moral disapproval of pornography itself (Grubbs et al., 2015a). Therefore, it is possible that the links between perceived addiction and struggle are partially accounted for by religious beliefs and moral disapproval of pornography use. Some prior work has postulated that perceived addiction is likely the result of dissonance between one’s sexual values and one’s sexual behavior (Grubbs et al., 2015a; Hook et al., 2015). If these prior interpretations are applied to the present work, it would stand to reason that such dissonance could ultimately lead to struggle. Cognitive dissonance is a known predictor of psychological distress and, as such, it is reasonable to interpret these results as an indication of a religious and spiritual response to dissonance related to deeply held religious and spiritual values (i.e., sexual values).

The present findings also speak to the potentially cyclic nature of perceived addiction. Although many models for cycles of sexual addiction have been proposed (e.g., Carnes, 2001; Carnes & Adams, 2013; Young, 2008), the present study implies the possibility of a cycle of perceived addiction. Prior work has substantively shown the role of religiously based moral scruples in the maintenance of feelings of perceived addiction (Bradley et al., 2016; Grubbs et al., 2015a; Thomas, 2016; Volk et al., 2016). Dissonance between sexual moral standards and actual behavior is associated with greater perceived addiction (Hook et al., 2015). Furthermore, religious and spiritual struggles are known predictors of concurrent perceived hypersexuality (Giordano & Cecil, 2014). The present study demonstrated that perceived addiction itself may lead to greater experience of religious and spiritual struggles, including moral struggles, up to 1 year later. Taken together with past research, these findings point to a potential cycle in which perceived addiction could both fuel and be fueled by religious and spiritual struggles, particularly those of a moral nature. Furthermore, such a potentiality is consistent with prior work in which religious and spiritual struggles may be seen as either primary in the etiology of distress or pathology, secondary to such distress or pathology, or cyclical with distress or pathology (e.g., Pargament, 2009).

We are not suggesting that clinicians should attempt to change their client’s beliefs about sexual behavior or encourage them to abandon a faith that may lead to dissonance. However, it may be helpful for clinicians to be aware that religious and spiritual struggles may be another avenue by which perceived addiction could lead to distress. When confronted with clientele experiencing either of these issues (i.e., religious and spiritual struggles or perceived sexual addiction), it may be beneficial for clinicians to be open to exploring both domains. Given that both religious and spiritual struggle and perceived addiction are related to the experience of psychological distress over time and that they are related to each other, assessing both of these domains in a clinical setting could provide valuable insight for therapeutic foci. Finally, simply providing clientele with an avenue to discuss their sexual behaviors and their feelings of religious and spiritual struggle may within itself be therapeutic, as many individuals have trepidation about discussing religious and spiritual struggles with others (Exline & Grubbs, 2011) or an unwillingness to discuss their sexuality with their therapist (Farber & Hall, 2002).

Limitations and Future Directions

The present work assessed the notion of perceived addiction to internet pornography and daily levels of internet pornography use. However, addiction is more than the time spent on a certain activity. The proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for hypersexual disorder did include indicators such as time spent in the addictive activity, but it also included other criteria such as failed cessation attempts, impairment, and severe consequences. It is possible that more full assessment of such domains may find that such indicators are also predictors of religious and spiritual struggle in the same way as perceived addiction seems to be. Even so, the purpose of the present work was to contrast the relative influence of perceived addiction to internet pornography and the influence of actual use of pornography on religious and spiritual struggle. Future work should account for the full range of addictive symptoms, rather than just pornography use itself.

We also noted that the mean values of both religious and spiritual struggles and pornography-related variables were relatively low (e.g., below the midpoint of the scales). Although the size of our samples allowed for the appropriate use of our selected analyses (e.g., regression-based analyses), even with slightly skewed variables, we would caution that the data from the present study may not be representative of samples that score high in perceived addiction, in religious and spiritual struggles, or in both. Indeed, emerging work suggests that the relationships between religiousness, spirituality, and sexual behaviors present differently in clinical samples (e.g., Reid et al., 2016). As such, there is a clear and present need for research examining these relationships in samples with higher levels of each key variable.

Additionally, the results of these studies are based purely on self-report data, the limitations of which are well known (Chan, 2009). However, given that a key interest of these studies was self-perceived addiction to Internet pornography, self-report seems appropriate. Finally, although the longitudinal nature of our findings imply a causal link of perceived addiction on struggle, given that there were only two timepoints in both studies, definitive causal inferences cannot be made. There is a need for future research involving multiple timepoints that allow for more definitive analyses of growth or change over time. Finally, as was mentioned earlier, it is fully possible that there could be a cyclical relationship of sorts occurring in which perceived addiction drives religious and spiritual struggles, in turn, contributing to the perceived addiction. These possibilities should be examined in future work.

Notes

Given that only two participants identified with a gender of “other” and that prior work has linked male gender to pornography use (e.g., Grubbs et al., 2015a; Malamuth et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2010; Wright, 2013b), only male gender was coded in analyses, with women and “other” being grouped together.

Although not specifically hypothesized, additional analyses examining potential moderating effects of levels of use and of gender were conducted. In both cases, no moderation was found. As such, moderation was not considered in subsequent analyses.

References

Abell, J. W., Steenbergh, T. A., & Boivin, M. J. (2006). Cyberporn use in the context of religiosity. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 34, 165–171.

Ahrold, T. K., Farmer, M., Trapnell, P. D., & Meston, C. M. (2011). The relationship among sexual attitudes, sexual fantasy, and religiosity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 619–630.

Anderson, B. (2007). Breaking the silence: A pastor goes public about his battle with pornography. Pittsburgh, PA: Autumn House Press.

Ano, G. G., & Pargament, K. I. (2013). Predictors of spiritual struggles: An exploratory study. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16, 419–434.

Bergner, R. M., & Bridges, A. J. (2002). The significance of heavy pornography involvement for romantic partners: Research and clinical implications. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 28, 193–206.

Bostwick, J. M., & Bucci, J. A. (2008). Internet sex addiction treated with naltrexone. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 83, 226–230.

Bradley, D. F., Grubbs, J. B., Uzdavines, A., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2016). Perceived addiction to internet pornography among religious believers and non-believers. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. doi:10.1080/10720162.2016.1162237.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk a new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5.

Carnes, P. (2001). Out of the shadows: Understanding sexual addiction. Center City: Hazelden Publishing.

Carnes, P., & Adams, K. M. (2013). Clinical management of sex addiction. New York: Routledge.

Cavaglion, G. (2008). Narratives of self-help of cyberporn dependents. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 15, 195–216.

Cavaglion, G. (2009). Cyber-porn dependence: Voices of distress in an Italian internet self-help community. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7, 295–310.

Chan, D. (2009). So why ask me? Are self-report data really that bad. In C. E. Lance & R. J. Vandenberg (Eds.), Statistical and methodological myths and urban legends: Doctrine, verity and fable in the organizational and social sciences (pp. 309–336). New York: Routledge.

Cooper, A. (1998). Sexuality and the internet: Surfing into the new millennium. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1, 187–193.

Cooper, A., Delmonico, D. L., & Burg, R. (2000). Cybersex users, abusers, and compulsives: New findings and implications. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 7, 5–29.

Driscoll, M. (2009). Porn-again Christian. Seattle, WA: ReLit.

Edelman, B. (2009). Red light states: Who buys online adult entertainment? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23, 209–220.

Egan, V., & Parmar, R. (2013). Dirty habits? Online pornography use, personality, obsessionality, and compulsivity. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 39, 394–409.

Eiser, J. R., Van der Pligt, J., Raw, M., & Sutton, S. R. (1985). Trying to stop smoking: Effects of perceived addiction, attributions for failure, and expectancy of success. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 8, 321–341.

Exline, J. J. (2013). Religious and spiritual struggles. In K. I. Pargament, J. J. Exline, & J. W. Jones (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality, Vol. 1: Context, theory, and research (pp. 459–475). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Exline, J. J., & Grubbs, J. B. (2011). “If I tell others about my anger toward God, how will they respond?” Predictors, associated behaviors, and outcomes in an adult sample. Journal of Psychology and Theology., 39, 304–315.

Exline, J. J., Grubbs, J. B., & Homolka, S. J. (2015). Seeing God as cruel or distant: Links with divine struggles involving anger, doubt, and fear of God’s disapproval. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 25, 29–41.

Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Grubbs, J. B., & Yali, A. M. (2014). The Religious and Spiritual Struggles Scale: Development and initial validation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6, 208–222.

Exline, J. J., Park, C. L., Smyth, J. M., & Carey, M. P. (2011). Anger toward God: Social-cognitive predictors, prevalence, and links with adjustment to bereavement and cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 129–148.

Farber, B. A., & Hall, D. (2002). Disclosure to therapists: What is and is not discussed in psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 359–370.

Fisher, W. A., & Barak, A. (2001). Internet pornography: A social psychological perspective on Internet sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 38, 312–323.

Gilliland, R., South, M., Carpenter, B. N., & Hardy, S. A. (2011). The roles of shame and guilt in hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 18, 12–29.

Giordano, A. L., & Cecil, A. L. (2014). Religious coping, spirituality, and hypersexual behavior among college students. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 21, 225–239.

Griffiths, M. (2000a). Does Internet and computer” addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3, 211–218.

Griffiths, M. (2000b). Excessive Internet use: Implications for sexual behavior. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 3, 537–552.

Grubbs, J. B., & Exline, J. J. (2014). Why did god make me this way? Anger at god in the context of personal transgressions. Journal of Psychology & Theology, 42, 315–325.

Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2014, August). Religiosity as a robust predictor of perceived addiction to internet pornography. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC.

Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., Hook, J. N., & Carlisle, R. D. (2015a). Transgression as addiction: Religiosity and moral disapproval as predictors of perceived addiction to pornography. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 125–136.

Grubbs, J. B., Sessoms, J., Wheeler, D. M., & Volk, F. (2010). The Cyber-pornography Use Inventory: The development of a new assessment instrument. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17, 106–126.

Grubbs, J. B., Stauner, N., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., & Lindberg, M. J. (2015b). Perceived addiction to Internet pornography and psychological distress: Examining relationships concurrently and over time. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29, 1056–1067.

Grubbs, J. B., Volk, F., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2015c). Internet pornography use: Perceived addiction, psychological distress, and the validation of a brief measure. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 41, 83–106.

Hald, G. M., & Malamuth, N. M. (2008). Self-perceived effects of pornography consumption. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 614–625.

Hook, J. N., Farrell, J. E., Davis, D. E., Van Tongeren, D. R., Griffin, B. J., Grubbs, J., … Bedics, J. D. (2015). Self-forgiveness and hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 22, 59–70.

Hook, J. N., Hook, J. P., Davis, D. E., Worthington, E. L., & Penberthy, J. K. (2010). Measuring sexual addiction and compulsivity: A critical review of instruments. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 36, 227–260.

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The Big Five Inventory: Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley: Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California.

Kane, D., Cheston, S. E., & Greer, J. (1993). Perceptions of God by survivors of childhood sexual abuse: An exploratory study in an underresearched area. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 21, 228–237.

Ley, D., Prause, N., & Finn, P. (2014). The emperor has no clothes: A review of the ‘pornography addiction’ model. Current Sexual Health Reports, 6, 94–105.

MacInnis, C. C., & Hodson, G. (2014). Do American States with more religious or conservative populations search more for sexual content on Google? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 137–147.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fritz, M. S., Williams, J., & Lockwood, C. M. (2007). Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 384–389.

Malamuth, N. M., Hald, G. M., & Koss, M. (2012). Pornography, individual differences in risk and men’s acceptance of violence against women in a representative sample. Sex Roles, 66, 427–439.

Murray-Swank, N. A., & Pargament, K. I. (2005). God, where are you? Evaluating a spiritually-integrated intervention for sexual abuse. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 8, 191–203.

Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Carroll, J. S. (2010). “I believe it is wrong but I still do it”: A comparison of religious young men who do versus do not use pornography. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2, 136–147.

Ogas, O., & Gaddam, S. (2011). A billion wicked thoughts: What the world’s largest experiment reveals about human desire. New York: Penguin Group.

Okoli, C. T., Richardson, C. G., Ratner, P. A., & Johnson, J. L. (2009). Non-smoking youths’ “perceived” addiction to tobacco is associated with their susceptibility to future smoking. Addictive Behaviors, 34, 1010–1016.

Pargament, K. I. (2009, October). Wrestling with the angels: Religious struggles in the context of mental illness. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., Tarakeshwar, N., & Hahn, J. (2001). Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients: A 2-year longitudinal study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161, 1881–1885.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., Tarakeshwar, N., & Hahn, J. (2004). Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: A two-year longitudinal study. Journal of Health Psychology, 9, 713–730.

Patterson, R., & Price, J. (2012). Pornography, religion, and the happiness gap: Does pornography impact the actively religious differently? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51, 79–89.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2009a). Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit internet material and notions of women as sex objects: Assessing causality and underlying processes. Journal of Communication, 59, 407–433.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2009b). Adolescents’ exposure to sexually explicit internet material and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study. Human Communication Research, 35, 171–194.

Piquet-Pessôa, M., Ferreira, G. M., Melca, I. A., & Fontenelle, L. F. (2014). DSM-5 and the decision not to include sex, shopping or stealing as addictions. Current Addiction Reports, 1, 172–176.

Pirutinsky, S., Rosmarin, D. H., Pargament, K. I., & Midlarsky, E. (2011). Does negative religious coping accompany, precede, or follow depression among Orthodox Jews? Journal of Affective Disorders, 132, 401–405.

R Development Core Team. (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: the R Foundation for Statistical Computing. ISBN: 3-900051-07-0. Available online at http://www.R-project.org/.

Reid, R. C., Carpenter, B. N., & Hook, J. N. (2016). Investigating correlates of hypersexual behavior in religious patients. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. doi:10.1080/10720162.2015.1130002.

Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 119–125.

Rosmarin, D. H., Bigda-Peyton, J. S., Öngur, D., Pargament, K. I., & Björgvinsson, T. (2013). Religious coping among psychotic patients: Relevance to suicidality and treatment outcomes. Psychiatry Research, 210, 182–187.

Shapiro, D. N., Chandler, J., & Mueller, P. A. (2013). Using Mechanical Turk to study clinical populations. Clinical Psychological Science, 1, 213–220.

Steele, V. R., Staley, C., Fong, T., & Prause, N. (2013). Sexual desire, not hypersexuality, is related to neurophysiological responses elicited by sexual images. Socioaffective Neuroscience & Psychology, 3, 20770. doi:10.3402/snp.v3i0.20770.

Stoeker, F., & Arterburn, S. (2009). Every man’s battle: Winning the war on sexual temptation one victory at a time. Colorado Springs, CO: WaterBrook Press.

Sungur, M. Z., & Gündüz, A. (2014). A comparison of DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 definitions for sexual dysfunctions: Critiques and challenges. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11, 364–373.

Thomas, J. N. (2013). Outsourcing moral authority: The internal secularization of Evangelicals’ anti-pornography narratives. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 52, 457–475.

Thomas, J. N. (2016). The development and deployment of the idea of pornography addiction within American evangelicalism. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 23, 182–195.

Tiede, V. (2012). When your husband is addicted to pornography: Healing your wounded heart. Greensboro, NC: New Growth Press.

Tofighi, D., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2011). RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 692–700.

Volk, F., Thomas, J. C., Sosin, L. S., Jacob, V. L., & Moen, C. E. (2016). Religiosity developmental context and sexual shame in pornography users: A serial mediation model. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. doi:10.1080/10720162.2016.1151391.

Wéry, A., & Billieux, J. (2015). Problematic cybersex: Conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. Addictive Behaviors. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.007.

Wilson, M. (2007). Hope after betrayal: Healing when sexual addiction invades your marriage. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications.

Wilt, J. A., Cooper, E. B., Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2016). Associations of perceived addiction to internet pornography with religious/spiritual and psychological functioning. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 23, 260–278.

Womack, S. D., Hook, J. N., Ramos, M., Davis, D. E., & Penberthy, J. K. (2013). Measuring hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20, 65–78.

Wright, P. J. (2013a). Internet pornography exposure and women’s attitude towards extramarital sex: An exploratory study. Communication Studies, 64, 315–336.

Wright, P. J. (2013b). US males and pornography, 1973–2010: Consumption, predictors, correlates. Journal of Sex Research, 50, 60–71.

Wright, P. J., Bae, S., & Funk, M. (2013). United States women and pornography through four decades: Exposure, attitudes, behaviors, individual differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1131–1144.

Wright, P. J., Tokunaga, R. S., & Bae, S. (2014). More than a dalliance? Pornography consumption and extramarital sex attitudes among married US adults. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3, 97–109.

Young, K. S. (2008). Internet sex addiction risk factors, stages of development, and treatment. American Behavioral Scientist, 52, 21–37.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the John Templeton Foundation (Grant # 36094) in funding this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grubbs, J.B., Exline, J.J., Pargament, K.I. et al. Internet Pornography Use, Perceived Addiction, and Religious/Spiritual Struggles. Arch Sex Behav 46, 1733–1745 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0772-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0772-9