Abstract

Perceived addiction to Internet pornography is increasingly a focus of empirical attention. The present study examined the role that religious belief and moral disapproval of pornography use play in the experience of perceived addiction to Internet pornography. Results from two studies in undergraduate samples (Study 1, N = 331; Study 2, N = 97) indicated that there was a robust positive relationship between religiosity and perceived addiction to pornography and that this relationship was mediated by moral disapproval of pornography use. These results persisted even when actual use of pornography was controlled. Furthermore, although religiosity was negatively predictive of acknowledging any pornography use, among pornography users, religiosity was unrelated to actual levels of use. A structural equation model from a web-based sample of adults (Study 3, N = 208) revealed similar results. Specifically, religiosity was robustly predictive of perceived addiction, even when relevant covariates (e.g., trait self-control, socially desirable responding, neuroticism, use of pornography) were held constant. In sum, the present study indicated that religiosity and moral disapproval of pornography use were robust predictors of perceived addiction to Internet pornography while being unrelated to actual levels of use among pornography consumers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Researchers and clinicians have long noted the seemingly addictive nature of certain sexual behaviors and practices, such as pornography use (e.g., Griffiths, 2012; Kafka, 2001, 2010; Young, 2008). Similarly, an ever-increasing amount of research suggests that many individuals believe themselves to be addicted to Internet pornography (e.g., Cavaglion, 2008; Dunn, Seaburne-May, & Gatter, 2012; Grubbs, Volk, Exline, & Pargament, 2014). Despite this growing body of literature, there is no officially recognized diagnosis related to addictive use of Internet pornography. This diagnostic void is due, in part, to skepticism about the notion of pornography addiction specifically and hypersexual behavior more broadly (e.g., Giles, 2006; Giugliano, 2009; Halpern, 2011; Moser, 2011).

Despite these controversies, many studies continue to document the proclivity of certain individuals to self-identify as addicted to Internet pornography (Egan & Parmar, 2013; Grubbs, Sessoms, Wheeler, & Volk, 2010; Pyle & Bridges, 2012). Although such self-labels are not diagnostically grounded, they do speak to the propensity of individuals to see their own behaviors as pathological. Such labels also arguably represent an area in need of more research. However, the psychosocial influences that may cause individuals to view their use of Internet pornography as addictive are poorly understood. In designing the present study, we wanted to examine the factors that are related to pathological interpretations of Internet pornography use. Specifically, we sought to examine the role that one factor–religiosity–may play in the experience of perceived addiction to Internet pornography.

Perceived Addiction to Internet Pornography

Internet pornography use has become extremely common in many countries (e.g., Lo & Wei, 2005; Traeen, Nilsen, & Stigum, 2006), one of those being the U.S. (e.g., Ybarra & Mitchell, 2005). Because of this, an ever-growing body of research is concerned with the potential effects of widespread Internet pornography use (Carroll et al., 2008; Hald & Malamuth, 2008). The vast majority of this research has focused on the potentially negative consequences associated with pornography use (for reviews, see Döring, 2009; Short, Black, Smith, Wetterneck, & Wells, 2012), such as compulsivity or addiction (Cooper, Scherer, Boies, & Gordon, 1999; Green, Carnes, Carnes, & Weinman, 2012; for a review, see Griffiths, 2012).

Many empirical (for a review, see Winkler, Dörsing, Rief, Shen, & Glombiewski, 2012) and theoretical (e.g., Cooper, 1998; Young, 2008) works have argued that individuals who view Internet pornography can become compulsive in their use. Some have posited that this purported compulsivity represents a distinct psychological disorder (Shapira et al., 2003) whereas others have suggested that it is simply a subset of hypersexual tendencies more broadly (e.g., Kafka, 2001; Kaplan & Krueger, 2010). Building on this interest, various diagnostic instruments now assess for hypersexuality broadly and problematic use of Internet pornography more specifically (for reviews, see Hook, Hook, Davis, Worthington, & Penberthy, 2010; Womack, Hook, Ramos, Davis, & Penberthy, 2013) and various treatments for both have been developed (for a review, see Hook, Reid, Penberthy, Davis, & Jennings, 2013). Yet, despite this proliferation of research, there is no official diagnosis for hypersexuality, much less compulsive use of Internet pornography.

The lack of a specific diagnosis addressing compulsive use of Internet pornography has led to a variety of definitions of Internet pornography addiction (Short et al., 2012). Some of these definitions have focused on objective behavior (e.g., more than 11 h of pornography use per week) (Cooper et al., 1999). Most definitions, however, have focused on the subjective experience of the individual, such as the perceived cycle of use (Young, 2008) or factors such as efforts in obtaining pornography, perceived lack of control, and distress regarding use (Grubbs et al., 2014).

For the present work, we sought to examine perceived addiction to Internet pornography, focusing on the tendency of some individuals to view their own use of pornography as compulsive or addictive. This distinct focus on perceived addiction to Internet pornography separates the present work from prior examinations of this topic. Rather than assuming that self-perceived addiction to Internet pornography indicates actual addictive behavior, we examined the tendency of individuals to make such self-diagnoses. Furthermore, given that many signs of psychological distress, such as general compulsivity (Egan & Parmar, 2013), depression and despair (Cavaglion, 2008; Philaretou, Mahfouz, & Allen, 2005), and anxiety (Grubbs et al., 2014), are associated with perceived addiction, the clinical relevance of examining perceived addiction is salient. In designing the present study, we were specifically concerned with examining factors that may be associated with perceived addiction.

Many aspects of personality are associated with perceived addiction to Internet pornography. For example, neuroticism is positively associated with perceived addiction (Egan & Parmar, 2013; Grubbs et al., 2014). Conversely, trait self-control is negatively associated with perceived addiction (Grubbs et al., 2014). Personal beliefs also appear to be associated with perceived addiction, as religiosity appears to be associated with greater reported addiction to Internet pornography (Abell, Steenbergh, & Boivin, 2006; Levert, 2007; Sessoms, Grubbs, & Exline, 2011). In the present study, we sought to examine this final association more closely.

Religiosity, Morality, and Pornography Use

Religious beliefs impact sexual attitudes (Lefkowitz, Gillen, Shearer, & Boone, 2004), sexual fantasy (Ahrold, Farmer, Trapnell, & Meston, 2011), and sexual behavior (Farmer, Trapnell, & Meston, 2009). Most often, the effects of religiosity on sexuality are prohibitive or stigmatic in nature (Ahrold et al., 2011). The same is true of pornography use. Religious individuals tend to disapprove of pornography use and support pornography censorship (Lambe, 2004; Lottes, Weinberg, & Weller, 1993; Thomas, 2013). Religiosity also predicts unhappiness and depressive tendencies among pornography users (Patterson & Price, 2012). Not surprisingly then, pornography use is reportedly lower in religious populations than secular populations (Carroll et al., 2008; Poulsen, Busby, & Galovan, 2013; Wright, 2013; Wright, Bae, & Funk, 2013). Even so, analyses of pornography sales reveal that more religious areas tend to purchase more pornography than less religious areas (Edelman, 2009). Furthermore, quite a number of religious individuals acknowledge using pornography, despite moral convictions against such use (Nelson, Padilla-Walker, & Carroll, 2010).

In designing the present study, we sought to examine a specific aspect of the relationship between religiosity and pornography use—the association between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography. Religiosity is typically associated with lower levels of addictive behavior patterns such as substance abuse and gambling (Feigelman, Wallisch, & Lesieur, 1998). Religiosity is also negatively associated with the use and acceptance of pornography (Carroll et al., 2008). In theory, then, one might expect an inverse association between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography. However, a growing body of research suggests that this is not the case.

A simple search for the term “Pornography Addiction” on the Amazon bookseller’s website returned over 1,200 results on the topic. Over half of these results were found within the “Religion and Spirituality” section of the online bookstore (Grubbs, Exline, & Volk, 2012). Such a simple finding raises a question about the relationship between religiosity and attitudes toward pornography: Could there be an association between religious belief and the notion of Internet pornography addiction? In support of this idea, several studies have found that religiosity and religious values were positively associated with perceived addiction to Internet pornography (Abell et al., 2006; Grubbs et al., 2010; Levert, 2007; Sessoms et al., 2011). Although some have speculated that this association is a function of prohibitive and moralistic religious beliefs (e.g., Kwee, Dominguez, & Ferrell, 2007), there is little empirical work examining why religiosity is positively associated with greater perceived addiction to Internet pornography.

In designing the present study, we noted that many religious systems define certain sexual practices as permissible and others as problematic. It is a short jump to suppose that such religious teachings may influence adherents’ views of sexuality and sexual behavior. Arguably, moralistic influences could lead to pathological interpretations of otherwise normal behaviors (Clarkson & Kopaczewski, 2013). For example, highly religious therapists are more likely to diagnose sexual addiction in their clientele than their nonreligious counterparts (Hecker, Trepper, Wetchler, & Fontaine, 1995). Given that therapists are presumably trained in accurate and unbiased diagnostic procedures, it seems likely that this tendency would be even more evident in the general population. Furthermore, in religious populations, guilt and shame often accompany sexual expression, which can lead to the pathologizing of developmentally normal sexual behaviors (for a theoretical review, see Kwee et al., 2007). As such, it may be that religious individuals have a tendency to interpret a potentially non-pathological behavior, such as Internet pornography use, as pathological. More simply, due to the moral reactions to pornography in religious populations, thinking of pornography use as addictive is a possibility.

In designing the present study, we sought to explore the relationship between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography more closely. Primarily, we hypothesized that religiosity would predict greater perceived addiction to Internet pornography, even when actual levels of pornography use and other relevant variables were controlled. Also, we predicted that the relationship between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography would be mediated by moral disapproval of pornography. In sum, we expected to find that, to the extent that religiosity predicted negative moralistic attitudes toward pornography use, it would also predict perceived addiction to Internet pornography among users.

Overview of Studies

To test our hypotheses, we conducted two cross-sectional analyses using three samples in the U.S. Study 1 used a sample of undergraduate students from secular universities (N = 331). Study 2 used a sample of undergraduate students from a religiously affiliated university (N = 97). Finally, Study 3 used a web-based sample of adults (N = 208).

Study 1

In order to initially test our hypotheses that religiosity would predict perceived addiction to Internet pornography and that moral disapproval of pornography use would mediate this link, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis in an undergraduate samples.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Our sample was taken from undergraduates (N = 725) enrolled in introductory psychology courses at one of two universities in the Midwest–a midsized private university and a large public university. Participants were offered partial course credit in exchange for their participation in a web-based survey. Due to the nature of the study, only those who acknowledged intentionally viewing pornography within the past 6 months were directed to complete pornography related measures (N = 331; 228 men, 103 women; M age = 19.5, SD = 1.9; see below for inclusion criteria). Primary racial affiliations reported were White/Caucasian (67 %), Asian/Pacific Islander (14 %), African American/Black (10 %), Latino/Hispanic (6 %), Native American/Alaska Native (2 %), Middle Eastern/Arabic descent (1 %). Participants identified primarily as heterosexual (88 %), followed by homosexual (5 %), bisexual (5 %), and undisclosed (2 %). Primary religious affiliations reported were Protestant or Evangelical Christian (36 %), Catholic Christian (23 %), New Age or Pagan (4 %), Jewish (2 %), Muslim (2 %), and Buddhist (1 %). Notably, a large percentage of participants reported that they were religiously unaffiliated (32 %). This category included a variety of those that identified as religious “nones” (Dougherty, Johnson, & Polson, 2007; Lim, MacGregor, & Putnam, 2010), such as atheists, agnostics, spiritual but not religious, and religiously ambivalent.

Measures

Unless otherwise indicated, we scored all measures by taking the average score across items (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s αs for all measures).

Religiosity

We assessed religious belief salience using a 5-item inventory adapted from Blaine and Crocker (1995), omitting one item that was specifically focused on deity, as not all participants may believe in a specific deity. Participants responded to items such as “Being a religious/spiritual person is important to me” on a scale of 0 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree). We also assessed participation in religious activities using an adaptation of an existing 5-item measure (Exline, Yali, & Sanderson, 2000). Participants indicated weekly frequency of religious activities, such as prayer and reading of sacred texts, on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 5 (more than once per day). To assess religiosity, we standardized the items from both measures and aggregated them into a single index. This assessment strategy has been used successfully in prior studies (e.g., Exline, Park, Smyth, & Carey, 2011).

Pornography

Participants were asked how often they had intentionally viewed pornography in the past 6 months. Response options included 0 times (n 1 = 395, n 2 = 224), 1–3 times (n 1 = 89; n 2 = 34), 4–6 times (n 1 = 47; n 2 = 20), 7–9 times (n 1 = 25; n 2 = 8), and 10 or more times (n 1 = 170; n 2 = 35). Given that assessing perceived addiction would only be relevant for actual users of online pornography, only those who indicated initially viewing pornography at least once in the past 6 months completed the relevant perceived addiction measures (Options 2–5; N 1 = 331; N 2 = 97). Participants also reported their estimated average daily use of pornography in hours, ranging from 0 to 12 h.

We assessed perceived addiction to Internet pornography using the Cyber Pornography Use Inventory-9 (CPUI-9) (Grubbs et al., 2014). This 9-item scale measures perceived addiction to Internet pornography using three, three-item subscales: Perceived Compulsivity (e.g., “I believe I am addicted to Internet pornography”), Access Efforts (e.g., “At times, I try to arrange my schedule so that I will be able to be alone to view pornography”), and Emotional Distress (e.g., “I feel ashamed after viewing pornography online”). Participants rated their agreement with items on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). The entire measure is listed in Appendix.

We assessed participants’ moral disapproval of pornography use with four items developed for this study: “Viewing pornography online troubles my conscience,” “Viewing pornography online violates my religious beliefs,” “I believe that viewing pornography online is morally wrong,” and “I believe viewing pornography online is a sin.” Participants rated their agreement with the statement from 1 (not at all) to 7 (extremely). Analyses indicated good internal consistency across samples (Table 1). Given that the wording of Items 2 and 4 may presuppose religious beliefs, thereby artificially inflating the association between moral disapproval and religiosity, we also calculated a two-item index of moral disapproval simply using Items 1 and 3. Results indicated an extremely high degree of correlation between the four-item scale and the two-item scale (r = .97, p < .001). Subsequent analyses using the two-item scale revealed highly similar results to analyses using the full four-item scale. Given these findings, we determined that the two religiously worded items did not likely artificially inflate the relationship between the four-item moral disapproval scale and religiosity. As such, the full, four-item measure was used in subsequent analyses.

Results

Given past research demonstrating substantial gender differences in Internet pornography use (e.g., Hald, 2006; Paul & Shim, 2008), we conducted a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) based on gender to determine if there were any systematic differences between men and women on key variables (religiosity, moral attitudes, CPUI-9). Results indicated significant multivariate differences between men and women for these variables, F(1, 330) = 7.88, p < .001; Pillai’s Trace = .082. Subsequent t-tests revealed that there were significant differences between men (M = 2.8, SD = 2.0) and women (M = 2.2, SD = 1.8) for moral disapproval of pornography use, t(2, 329) = 2.2, p = .031. Results also revealed significant differences between men (M = 2.3, SD = 1.3) and women (M = 1.9, SD = 1.2) for the total CPUI-9 score, t(2, 329) = 3.0, p = .003. Finally, there were no significant differences between genders for religiosity.

We also conducted logistic regression analyses on all users to determine if religiosity would be associated with use in the total sample (N = 725). Results revealed that religiosity was significantly and negatively predictive of endorsing any pornography use in the past 6 months (β = −.32, p = .002). However, among those acknowledging pornography use in the past 6 months, Pearson correlations revealed that religiosity was unrelated to the number of hours of Internet pornography use. In sum, although religiosity predicted less use in the total sample, among users of Internet pornography, religiosity was wholly unrelated to actual amount of time spent viewing pornography online.

Our main hypotheses were that (1) religiosity would be positively related to perceived addiction to Internet pornography, (2) this association would hold even when controlling for actual pornography use, and (3) this association would be mediated by moral disapproval of pornography use. To examine the hypothesis that religiosity would be positively related to perceived addiction to Internet pornography, we conducted Pearson correlations between these variables (Table 2). Notably, we found positive associations between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography.

To examine the hypothesis that the association between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography would hold even when controlling for actual pornography use, we conducted a hierarchical regression (Table 3). In the first step of this analysis, we introduced use of pornography as a relevant control variable. In the second step, we introduced religiosity as a predictor (Table 3). Notably, in the first step, actual use of pornography was positively associated with perceived addiction. In the second step, religiosity emerged as a positive predictor of perceived addiction, accounting for substantial variance. Thus, religiosity was a robust predictor of perceived addiction to Internet pornography, even when the actual use of pornography was controlled.

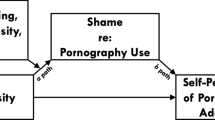

To examine the hypothesis that the relationship between perceived addiction and religiosity would be mediated by moral disapproval of pornography use, we conducted a mediation analysis. All mediation analyses were conducted using the Process Macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2013) and controlled for the number of hours viewing pornography. Consistent with hypotheses, we found that the relationship between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography was mediated by moral disapproval of pornography use (Fig. 1). Specifically, we found that moral disapproval mediated the relationship between religiosity and perceived addiction (Sobel’s z = 8.36; p < .001). We further found that religiosity had a substantial indirect effect (Preacher & Kelley, 2011) on perceived addiction to Internet pornography through moral disapproval (indirect effect = .63, 95 % CI = .45−.79). Collectively, these findings strongly supported our hypotheses that religiosity would be robustly predictive of perceived addiction to Internet pornography and that moral disapproval of Internet pornography would mediate this relationship.

Mediation model predicting perceived addiction to Internet pornography. Coefficients for Study 1 are reported before (to the left) of each slash. Coefficients for Study 2 are reported after (to the right) of each slash. Study 1, F(2, 329) = 72.9; R 2 = .43; p < .001; Study 2, F(2, 95) = 18.9; R 2 = .44; p < .001, to the right of slash. **p < .01 (two-tailed)

Study 2

Given that previous analyses have shown that samples derived from religiously affiliated institutions report higher levels of addiction to Internet pornography despite no indications of greater use (Sessoms et al., 2011), we sought to replicate our findings in Study 1 in a religious sample. To this end, we conducted a replication of Study 1 in a sample of undergraduates at a religiously affiliated university.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were undergraduates enrolled in introductory psychology courses at a Christian-affiliated university in the southern United States (N = 321). Students were offered partial course credit for their participation in a web-based survey. Only those who indicated intentionally viewing pornography within the past 6 months were directed to complete pornography related variables (N = 97, 49 men, 48 women; M age = 19.5 years, SD = 1.3). Primary racial affiliations reported were White/Caucasian (54 %), Latino/Hispanic (17 %), Asian/Pacific Islander (14 %), African American/Black (11 %), Middle Eastern/Arabic descent (2 %), Native American/Alaska Native (1 %). Participants identified primarily as heterosexual (89 %), followed by homosexual (6 %), bisexual (4 %), and undisclosed (1 %). Primary religious affiliations reported were Protestant or Evangelical Christian (55 %), religiously unaffiliated (26 %), Catholic Christian (18 %), and Buddhist (1 %).

Measures

The measures were identical to those described in Study 1 (Table 1).

Results

We examined gender differences on key variables (Religiosity, Moral Disapproval, CPUI-9) in this sample. MANOVA again revealed systematic differences between men and women on key variables, F(3, 93) = 3.5, p = .017. However, subsequent t-tests revealed no significant differences on any key variable individually. These results indicated that there were differences between genders, but that these differences were a function of multivariate variance, rather than specific differences between groups.

We again conducted logistic regression using the entire sample to determine if religiosity would be associated with use in the total sample (N = 321). Again, we found that religiosity was significantly and negatively predictive of endorsing any pornography use in the past 6 months (β = −.78, p < .001). Similar to Study 1, we again found that, among those acknowledging use in the past 6 months, religiosity was unrelated to the number of hours of Internet pornography use on a daily basis (Table 2).

To examine the hypothesis that religiosity would be positively related to perceived addiction to Internet pornography, we conducted Pearson correlations between these variables (Table 2). In keeping with our findings from Study 1, we again found positive associations between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography.

To examine the hypothesis that the association between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography would hold even when controlling for actual pornography use, we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis (Table 3). In a replication of the findings from Study 1, we again found that, in the first step, actual use of pornography was positively associated with perceived addiction. In the second step, religiosity emerged as a positive predictor of perceived addiction, accounting for substantial variance.

To examine the hypothesis that the relationship between perceived addiction and religiosity would be mediated by moral disapproval of pornography use, we conducted mediation analyses in each sample, again controlling for time spent viewing pornography. Again, consistent with findings from Study 1, we found that the relationship between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography was mediated by moral disapproval of pornography use (Fig. 1), Sobel’s z = 3.59, p < .001, and religiosity demonstrated a substantial indirect effect on perceived addiction (indirect effect = .42, 95 % CI = .22−.71). These findings again supported our hypotheses that religiosity would be robustly and indirectly predictive of perceived addiction to Internet pornography through moral disapproval of Internet pornography use.

Study 3

In our third study, we expanded upon the findings of Studies 1 and 2 to include known predictors of perceived addiction to Internet pornography, such as neuroticism, self-control, and socially desirable responding. We further sought to more rigorously examine the notion of perceived addiction to Internet pornography by assessing general levels of hypersexuality. Finally, we sought to extend these findings to a more general sample of adults in the U.S., rather than simply among college students.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants in the U.S. (N = 434) were recruited via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk workforce database, an online marketplace where individuals may contract to perform small tasks over the Internet for monetary compensation. Previous social science research has found that samples derived from this source are essentially equivalent to conventional sampling methods and suitable for cross-sectional research (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011). Participants were paid $1 for their participation in a brief survey entitled “Personality, Beliefs, and Transgression.” Pornography related measures were only administered to those adults who acknowledged viewing pornography online in the past month (N = 208; 136 men, 72 women; M age = 31.8 years, SD = 10.6). The predominant ethnicity reported was Caucasian or White (79 %), followed by Asian or Pacific Islander (8 %), African-American (6 %), Latino or Hispanic (5 %), and other (2 %). Participants identified primarily as heterosexual (79 %), followed by bisexual (10 %), homosexual (7 %), and undisclosed (4 %). Primary religious affiliations reported were Protestant or evangelical Christian (35 %), religiously unaffiliated (31 %), Catholic Christian (20 %), Hindu (5 %), New Age or Pagan (4 %), Buddhist (3 %), and Jewish (2 %).

Measures

Unless otherwise indicated, we scored measures by averaging across scale items (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s αs for all measures).

Religiosity

We assessed religiosity using the same method described in Study 1, calculating a standardized index reflecting both belief salience and religious activity.

Pornography

Perceived addiction to Internet pornography was assessed using the CPUI-9 (see Study 1). Pornography use was evaluated by directly asking participants how many hours on average they viewed pornography per day. Moral disapproval of pornography was assessed using the same method described in Study 1.

Hypersexuality

We included the Kalichman Sexual Compulsivity Scale (Kalichman & Rompa, 1995) as a broad measure of perceived levels of general hypersexuality. This 10-item scale requires participants to rate agreement on a scale of 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me) with items such as “I feel that sexual thoughts and feelings are stronger than I am,” “I have to struggle to control my sexual thoughts and behavior,” and “My sexual thoughts and behaviors are causing problems in my life.”

Neuroticism

We used the neuroticism subscale of the Big Five Inventory-44 (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991). Participants responded to the prompt “Do you agree that you are someone who:” by rating their agreement with descriptors such as, “worries a lot,” “can be moody,” and “gets nervous easily.” Responses were recorded on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Self-Control

We included the brief version of the Self-Control Scale (Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). Participants rated agreement with 13 items, such as “I refuse things that are bad for me,” “People would say that I have iron self-discipline,” and “I am good at resisting temptation.” Responses were recorded on a scale of 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (very much like me).

Social Desirability

We included the 13-item version of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Reynolds, 1982). Participants respond to items such as “Sometimes it is hard for me to go on with my work without encouragement,” “I’m always willing to admit it when I make a mistake,” and “I have never deliberately said something that hurt someone’s feelings.” Responses were recorded in a True/False format. The total score is calculated by summing socially desirable responses, with higher scores indicating greater levels of impression management.

Results and Discussion

In keeping with the analyses conducted in Studies 1 and 2, we conducted MANOVA to determine if there were systematic differences on key variables (Religiosity, Moral Disapproval, CPUI-9, and Sexual Compulsivity) by gender. Notably, MANOVA results indicated that there were no systematic differences for men and women, F(4, 203) = 1.7.

Consistent with the results of Studies 1 and 2, binary logistic regression analyses revealed that religiosity was negatively related to pornography use in the total sample (N = 434, β = −.27, p < .001), but wholly unrelated to pornography use among those who admitted viewing pornography online. Religious individuals were substantially less likely to report viewing pornography within the past month, but, among those that did, religiosity was not associated with actual amount of use.

Our main hypotheses were that (1) religiosity would be positively related to perceived addiction to Internet pornography, (2) this association would hold even when controlling for actual pornography use and other variables associated with perceived addiction to Internet pornography, and (3) this association would be mediated by moral disapproval of pornography use. To examine our hypothesis that religiosity would be positively associated with perceived addiction, we conducted Pearson correlations (Table 4). Consistent with the results of Study 1, we found that religiosity was positively associated with perceived addiction to Internet pornography.

To examine our hypotheses that religiosity would robustly predict perceived addiction to Internet pornography and that this relationship would be mediated by moral disapproval of pornography use, we conducted structural analyses. In keeping with previous research (e.g., Egan & Parmar, 2013), we conceptualized perceived addiction to Internet pornography as a latent variable. In so doing, we measured perceived addiction in a manner slightly differently than we did in Study 1. This latent variable Perceived Addiction was evidenced by three observed variables: the Perceived Compulsivity subscale of the CPUI-9, the Access Efforts subscale of the CPUI-9, and the Kalichman Sexual Compulsivity Scale. By defining perceived addiction in this manner, we sought to examine that aspect of perceived addiction that is associated with pathological interpretations of pornography use (Perceived Compulsivity), pornography-specific behaviors (Access Efforts), and general hypersexual tendencies (Kalichman Sexual Compulsivity Scale). To avoid any possibility of conceptual overlap between Moral disapproval (e.g., “Viewing pornography online troubles my conscience”) and emotional distress about pornography use (e.g., “I feel ashamed after viewing pornography online”), the Emotional Distress subscale of the CPUI-9 was omitted from this analysis.

Within the structural model, we included neuroticism, self-control, socially desirable responding, and daily use of pornography as relevant covariates of perceived addiction (Egan & Parmar, 2013; Grubbs et al., 2014). For the sake of clarity, these covariates were omitted from the structural diagram. We predicted that moral disapproval of pornography use would not only predict the latent variable Perceived Addiction (Fig. 2) but would also predict residual variance in the observed variable Perceived Compulsivity. Perceived Compulsivity is the most direct measure of pathological interpretations of pornography use (e.g., “I am addicted to Internet pornography.”). We thus expected to find that moral disapproval would predict both the aspect of perceived addiction associated with sexual compulsivity and actual access efforts, as well as the residual variance in perceptions of compulsivity. We further expected to find a significant indirect effect of religiosity on perceived addiction, through moral disapproval. Finally, we allowed for residual covariance between the observed variables Sexual Compulsivity and Access Efforts, as past work (Grubbs et al., 2014) and current correlations suggested moderate-to-strong relationships between the two.

Structural model predicting perceived internet pornography addiction, χ2 (16, N = 208) = 17.51, p = .28, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .02, p(RMSEA < .05) = .91, SRMR = .04. Note Self-Control (β = −.30, p = .001), Pornography Use in Hours (β = .57, p < .001), Neuroticism (β = −.04), and Social Desirability (β = −.07) were included in the model, but omitted from the structural diagram for the sake of clarity. *p < .05 (two-tailed); **p < .01 level (two-tailed)

All analyses were conducted using the Lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012) for R Statistical Software (R Development Core Team, 2008). Missing data were estimated using Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation. The results of our model are summarized in Fig. 2. Analysis of the original model revealed a good fit, χ2 (16, N = 208) = 17.51, p = .28, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .02, p(RMSEA < .05) = .91, SRMR = .04. Within this model, moral disapproval of pornography use positively predicted both the latent variable Perceived Addiction and residual variance in the observed variable Perceived Compulsivity. In both cases, a significant indirect effect of religiosity was observed. Although omitted from the structural diagram for clarity’s sake, we noted that actual use of pornography (β = .57, p < .001) and trait self-control (β = −.30, p = .001) both emerged as significant predictors of perceived addiction. Even so, religiosity and moral disapproval maintained significance in predicting perceived addiction. Collectively, these findings strongly support our hypothesis that religiosity would be broadly predictive of perceived addiction to Internet pornography. Finally, we noted that the predicted residual covariance between Sexual Compulsivity and Access Efforts was negative, contrary to expectations. When the shared variance of perceived addiction was controlled, the remaining relationship between general sexual compulsivity and efforts in obtaining pornography was negative. In sum, these results extended the findings of Studies 1 and 2 to a diverse sample of adults in the U.S. and demonstrated the robustness of these associations by controlling for a range of logical covariates.

General Discussion

At the outset of this study, we hypothesized that religiosity would be broadly predictive of greater perceived addiction to Internet pornography among pornography users. Across three studies, we consistently found support for this hypothesis. Religiosity predicted greater perceived addiction, although it did not predict greater levels of use among religious individuals who acknowledged using pornography. Actual use of pornography was also positively associated with perceived addiction, indicating that perceived addiction to Internet pornography is indeed associated with increased use. However, religiosity consistently predicted unique variance in perceived addiction, above and beyond the contribution made by actual use. This relationship persisted even when relevant variables such as neuroticism, self-control, and socially desirable responding were all controlled.

Religiosity and Moral Disapproval of Pornography

Consistent with hypotheses, the link between religiosity and perceived addiction to Internet pornography was reliably mediated by moral disapproval of pornography use. In two undergraduate samples (Studies 1 and 2), this mediation was clear. Religiosity predicted more negative moral attitudes about pornography use, which in turn predicted greater perceived addiction. In a broad-based sample of adults (Study 3), moral disapproval again mediated the link between religiosity and perceived addiction. Again, we found that the indirect effect of religiosity on perceived addiction was substantial and robust. These findings collectively suggest that the previously documented association between religiosity and perceived addiction is likely accomplished through the relationship that religiosity has with sexual values and moral disapproval of certain sexual behaviors.

Previously, there has been speculation that religiosity may be linked to greater levels of addiction to pornography as such an addiction provides an escape from the scruples of oppressive religious ideology, such as right wing authoritarianism (Levert, 2007). Although such an interpretation could be applied to the present work, we contend that an alternate explanation is more likely. Specifically, religious individuals often experience profound guilt over behaviors deemed transgressions (Abramowitz, Huppert, Cohen, Tolin, & Cahill, 2002; Grubbs et al., 2010; Kwee et al., 2007). Further research with religious individuals has found that events thought to be desecrations of sacred religious values are often associated with a wide range of negative interpretations and outcomes (Pargament, Magyar, Benore, & Mahoney, 2005). Should religious individuals view using pornography as a desecration of spiritual values, pathological interpretations of that use could arise. In essence, if the religious individual were to feel that pornography use desecrated a sacred religious value, (e.g., sexual purity), harsh reactions and pathological interpretations would be likely. Given that moral disapproval of pornography use seems to be a primary vehicle by which religiosity predicts perceived addiction, such an effect may be occurring here as well. Our findings strongly indicate that moralistic perceptions of pornography are strongly associated with individual perceptions of personal pornography use. Feelings of addiction could be seen as the religious individual’s pathological interpretation of a behavior deemed a transgression or a desecration of sexual purity. Such a possibility is speculative at this point, but it seems rational considering the nature of our findings. Furthermore, such a possibility illustrates an important possibility for future research examining the link between religious values and pathological interpretations of behavior.

The implications of the present work are multifaceted. Much prior research suggests that religiosity is related to negative attitudes toward pornography (Lambe, 2004; Thomas, 2013), reduced acceptance of pornography (Carroll et al., 2008), and less use of pornography (Wright, 2013). In keeping with that trend, we also found that religiosity was robustly and strongly related to moral disapproval of pornography use. These moral attitudes, in turn, were strongly associated with perceived addiction to Internet pornography. These findings are theoretically consistent with broader critiques of hypersexuality (e.g., Clarkson & Kopaczewski, 2013), in that moral disapproval predicted pathological interpretations of behaviors rather than pathological behaviors themselves. While religiosity was predictive of less pornography use in the general population, among pornography consumers, religiosity was not related levels of use, despite its profound relationship with pathological perceptions of use.

Finally, an overarching implication of our findings is related to future research in the domain of Internet pornography addiction. Our findings suggest that the evaluation of religiosity and moral attitudes toward sexual behavior may be an important aspect of assessing perceived addiction to Internet pornography. Given the extremely robust links between religiosity and perceived addiction, we contend that future research in this domain would benefit from controlling for religiosity and moral disapproval as potential covariates of these constructs.

Limitations and Future Directions

There were several limitations to the present study. Primarily, the data represented in the current work were exclusively self-report. Although socially desirable responding was controlled in Study 3, self-report data represent only one potential source of information in this type of research. Given that the focus of the present study was on the relationship between religiosity and individuals’ perceptions, self-report data about such perceptions was necessary. Even so, self-report data is limited in its ability to examine the nuances of human behavior. Including more objective criteria examining the relationship between religiosity and sexual behavior would benefit future work. Furthermore, the present study was limited to a series of samples in the US, primarily reflecting Christian religious affiliations. As such, it is yet to be determined if our findings are generalizable to other religious and cultural settings. We also noted sporadic gender differences in our studies on key variables. It is possible that such differences, although not consistent across studies, are indicative of greater differences between men and women regarding pornography use and moral disapproval. As a number of studies have shown that men and women differ in their use of pornography and attitudes toward pornography (Hald, 2006), future work should consider more explicitly the role that gender may play in the relationships described in this study. Finally, given that our findings were cross-sectional in nature, inferences about causation cannot be made. Although the described model implies that religiosity may cause pathological interpretations of behavior, such conclusions cannot be made authoritatively until more definitive, longitudinal research has been conducted.

References

Abell, J. W., Steenbergh, T. A., & Boivin, M. J. (2006). Cyberporn use in the context of religiosity. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 34, 165–171.

Abramowitz, J. S., Huppert, J. D., Cohen, A. B., Tolin, D. F., & Cahill, S. P. (2002). Religious obsessions and compulsions in a non-clinical sample: The Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity (PIOS). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 825–838.

Ahrold, T. K., Farmer, M., Trapnell, P. D., & Meston, C. M. (2011). The relationship among sexual attitudes, sexual fantasy, and religiosity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 619–630.

Blaine, B., & Crocker, J. (1995). Religiousness, race, and psychological well-being: Exploring social psychological mediators. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 1031–1041.

Buhrmester, M., Kwang, T., & Gosling, S. D. (2011). Amazon’s mechanical turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5.

Carroll, J. S., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Nelson, L. J., Olson, C. D., Barry, C. M., & Madsen, S. D. (2008). Generation XXX: Pornography acceptance and use among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23, 6–30.

Cavaglion, G. (2008). Narratives of self-help of cyberporn dependents. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 15, 195–216.

Clarkson, J., & Kopaczewski, S. (2013). Pornography addiction and the medicalization of free speech. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 37, 128–148.

Cooper, A. (1998). Sexuality and the Internet: Surfing into the new millennium. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 1, 187–193.

Cooper, A., Scherer, C. R., Boies, S. C., & Gordon, B. L. (1999). Sexuality on the Internet: From sexual exploration to pathological expression. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 30, 154–164.

Döring, N. M. (2009). The Internet’s impact on sexuality: A critical review of 15 years of research. Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 1089–1101.

Dougherty, K. D., Johnson, B. R., & Polson, E. C. (2007). Recovering the lost: Remeasuring US religious affiliation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 46, 483–499.

Dunn, N., Seaburne-May, M., & Gatter, P. (2012). Internet sex addiction: A licence to lust? Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 18, 270–277.

Edelman, B. (2009). Markets: Red light states: Who buys online adult entertainment? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23, 209–220.

Egan, V., & Parmar, R. (2013). Dirty habits? Online pornography use, personality, obsessionality, and compulsivity. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39, 394–409.

Exline, J. J., Park, C. L., Smyth, J. M., & Carey, M. P. (2011). Anger toward God: Social-cognitive predictors, prevalence, and links with adjustment to bereavement and cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100, 129–148.

Exline, J. J., Yali, A. M., & Sanderson, W. C. (2000). Guilt, discord, and alienation: The role of religious strain in depression and suicidality. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 1481–1496.

Farmer, M. A., Trapnell, P. D., & Meston, C. M. (2009). The relation between sexual behavior and religiosity subtypes: A test of the secularization hypothesis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 852–865.

Feigelman, W., Wallisch, L. S., & Lesieur, H. R. (1998). Problem gamblers, problem substance users, and dual-problem individuals: An epidemiological study. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 467–470.

Giles, J. (2006). No such thing as excessive levels of sexual behavior. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 641–642.

Giugliano, J. R. (2009). Sexual addiction: Diagnostic problems. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7, 283–294.

Green, B. A., Carnes, S., Carnes, P. J., & Weinman, E. A. (2012). Cybersex addiction patterns in a clinical sample of homosexual, heterosexual, and bisexual men and women. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 19, 77–98.

Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Internet sex addiction: A review of empirical research. Addiction Research & Theory, 20, 111–124.

Grubbs, J. B., Exline, J. J., and Volk, F. (2012, August). Internet pornography and spiritual struggle: A preliminary analysis. Presentation at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Orlando, FL.

Grubbs, J. B., Sessoms, J., Wheeler, D. M., & Volk, F. (2010). The Cyber-Pornography Use Inventory: The development of a new assessment instrument. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 17, 106–126.

Grubbs, J. B., Volk, F., Exline, J. J., & Pargament, K. I. (2014). Internet pornography use: Perceived addiction, psychological distress, and the validation of a brief measure. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2013.842192.

Hald, G. M. (2006). Gender differences in pornography consumption among young heterosexual Danish adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 577–585.

Hald, G. M., & Malamuth, N. M. (2008). Self-perceived effects of pornography consumption. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 614–625.

Halpern, A. L. (2011). The proposed diagnosis of hypersexual disorder for inclusion in DSM-5: Unnecessary and harmful [Letter to the Editor]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 487–488.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York, NY: Guilford.

Hecker, L. L., Trepper, T. S., Wetchler, J. L., & Fontaine, K. L. (1995). The influence of therapist values, religiosity and gender in the initial assessment of sexual addiction by family therapists. American Journal of Family Therapy, 23, 261–272.

Hook, J. N., Hook, J. P., Davis, D. E., Worthington, E. L., & Penberthy, J. K. (2010). Measuring sexual addiction and compulsivity: A critical review of instruments. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 36, 227–260.

Hook, J. N., Reid, R. C., Penberthy, J. K., Davis, D. E., & Jennings, D. J. (2013). Methodological review of treatments for non-paraphilic hypersexual behavior. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2012.751075.

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The Big Five Inventory: Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

Kafka, M. P. (2001). The paraphilia-related disorders: A proposal for a unified classification of nonparaphilic hypersexuality disorders. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 8, 227–239.

Kafka, M. P. (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 377–400.

Kalichman, S. C., & Rompa, D. (1995). Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: Reliability, validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65, 586–601.

Kaplan, M. S., & Krueger, R. B. (2010). Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of hypersexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 47, 181–198.

Kwee, A. W., Dominguez, A. W., & Ferrell, D. (2007). Sexual addiction and Christian college men: Conceptual, assessment, and treatment challenges. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 26, 3–13.

Lambe, J. L. (2004). Who wants to censor pornography and hate speech? Mass Communication & Society, 7, 279–299.

Lefkowitz, E. S., Gillen, M. M., Shearer, C. L., & Boone, T. L. (2004). Religiosity, sexual behaviors, and sexual attitudes during emerging adulthood. Journal of Sex Research, 41, 150–159.

Levert, N. P. (2007). A comparison of Christian and non-Christian males, authoritarianism, and their relationship to Internet pornography addiction/compulsion. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 14, 145–166.

Lim, C., MacGregor, C. A., & Putnam, R. D. (2010). Secular and liminal: Discovering heterogeneity among religious nones. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 49, 596–618.

Lo, V. H., & Wei, R. (2005). Exposure to Internet pornography and Taiwanese adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 49, 221–237.

Lottes, I., Weinberg, M., & Weller, I. (1993). Reactions to pornography on a college campus: For or against? Sex Roles, 29, 69–89.

Moser, C. (2011). Hypersexual disorder: Just more muddled thinking [Letter to the Editor]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 227–229.

Nelson, L. J., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Carroll, J. S. (2010). “I believe it is wrong but I still do it”: A comparison of religious young men who do versus do not use pornography. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 2, 136–147.

Pargament, K. I., Magyar, G. M., Benore, E., & Mahoney, A. (2005). Sacrilege: A study of sacred loss and desecration and their implications for health and well-being in a community sample. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 44, 59–78.

Patterson, R., & Price, J. (2012). Pornography, religion, and the happiness gap: Does pornography impact the actively religious differently? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51, 79–89.

Paul, B., & Shim, J. W. (2008). Gender, sexual affect, and motivations for Internet pornography use. International Journal of Sexual Health, 20, 187–199.

Philaretou, A. G., Mahfouz, A. Y., & Allen, K. R. (2005). Use of Internet pornography and men’s well-being. International Journal of Men’s Health, 4, 149–169.

Poulsen, F. O., Busby, D. M., & Galovan, A. M. (2013). Pornography use: Who uses it and how it is associated with couple outcomes. Journal of Sex Research, 50, 72–83.

Preacher, K. J., & Kelley, K. (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16, 93–115.

Pyle, T. M., & Bridges, A. J. (2012). Perceptions of relationship satisfaction and addictive behavior: Comparing pornography and marijuana use. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1, 171–179.

R Development Core Team. (2008). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Reynolds, W. M. (1982). Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38, 119–125.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48. Retrieved from http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02.

Sessoms, J., Grubbs, J. B., & Exline, J. J. (2011, April). The Cyber-Pornography Use Inventory: A comparison of a religious and secular sample. Poster presented at the Conference on Religion and Spirituality, Columbia, MD.

Shapira, N. A., Lessig, M. C., Goldsmith, T. D., Szabo, S. T., Lazoritz, M., Gold, M. S., et al. (2003). Problematic internet use: Proposed classification and diagnostic criteria. Depression and Anxiety, 17, 207–216.

Short, M. B., Black, L., Smith, A. H., Wetterneck, C. T., & Wells, D. E. (2012). A review of internet pornography use research: Methodology and content from the past 10 years. CyberPsychology, Behavior & Social Networking, 15, 13–23.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72, 271–324.

Thomas, J. N. (2013). Outsourcing moral authority: The internal secularization of Evangelicals’ anti-pornography narratives. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 52, 457–475.

Traeen, B., Nilsen, T. S. R., & Stigum, H. (2006). Use of pornography in traditional media and on the Internet in Norway. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 245–254.

Winkler, A., Dörsing, B., Rief, W., Shen, Y., & Glombiewski, J. A. (2013). Treatment of Internet addiction: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 317–329.

Womack, S. D., Hook, J. N., Ramos, M., Davis, D. E., & Penberthy, J. K. (2013). Measuring hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20, 65–78.

Wright, P. J. (2013). US males and pornography, 1973-2010: Consumption, predictors, correlates. Journal of Sex Research, 50, 60–71.

Wright, P. J., Bae, S., & Funk, M. (2013). United States women and pornography through four decades: Exposure, attitudes, behaviors, individual differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1131–1144.

Ybarra, M. L., & Mitchell, K. J. (2005). Exposure to Internet pornography among children and adolescents: A national survey. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 8, 473–486.

Young, K. S. (2008). Internet sex addiction risk factors, stages of development, and treatment. American Behavioral Scientist, 52, 21–37.

Acknowledgments

In funding Study 1, we gratefully acknowledge support from the John Templeton Foundation, Grant # 36094: Study 3 was funded by a Research Seed Award Grant awarded to the first author of this manuscript by the American Psychological Association’s Division 36 (The Society for the Psychology of Religion and Spirituality).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grubbs, J.B., Exline, J.J., Pargament, K.I. et al. Transgression as Addiction: Religiosity and Moral Disapproval as Predictors of Perceived Addiction to Pornography. Arch Sex Behav 44, 125–136 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0257-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0257-z