Abstract

In America, religiosity and conservatism are generally associated with opposition to non-traditional sexual behavior, but prominent political scandals and recent research suggest a paradoxical private attraction to sexual content on the political and religious right. We examined associations between state-level religiosity/conservatism and anonymized interest in searching for sexual content online using Google Trends (which calculates within-state search volumes for search terms). Across two separate years, and controlling for demographic variables, we observed moderate-to-large positive associations between: (1) greater proportions of state-level religiosity and general web searching for sexual content and (2) greater proportions of state-level conservatism and image-specific searching for sex. These findings were interpreted in terms of the paradoxical hypothesis that a greater preponderance of right-leaning ideologies is associated with greater preoccupation with sexual content in private internet activity. Alternative explanations (e.g., that opposition to non-traditional sex in right-leaning states leads liberals to rely on private internet sexual activity) are discussed, as are limitations to inference posed by aggregate data more generally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

American religiosity and conservatism generally discourage open and hedonistic sexuality in favor of more traditional sexual values (e.g., monogamous, married, heterosexual sex). For example, both religiosity and conservatism are associated with strong opposition to premarital sex (Altemeyer, 1996; Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001; Sakalh-Uğurlu & Glick, 2003), pornography (Carroll et al., 2008; Fisher, Cook, & Shirkey, 1994; Sherkat & Ellison, 1997), and homosexuality (Hunsberger & Jackson, 2005; Whitley, 1999). Despite espousing sexual conservatism, however, devoutly religious or conservative leaders are often exposed engaging in sexual behaviors that they publically oppose or campaign against. Consider George Rekers, the minister and anti-gay activist (and a clinical psychologist by training) discovered secretly vacationing with a male escort hired from rentboy.com (Nagrav, 2010) or David Vitter, the married Republican senator and advocate against premarital and extramarital sex uncovered as a regular client of a prostitution ring (Nossiter, 2007). There are, of course, prominent examples of sexual scandals on the political left, but the right advocates most strenuously against non-traditional sexual behavior, making such examples psychologically interesting. Might the ideological right in the U.S. be particularly preoccupied with or drawn to sex (e.g., Freud, 1936) where opposition to non-traditional sexuality paradoxically coincides with an actual interest in and attraction to sex/sexual content in private life?

Historically, theorists indeed specified “exaggerated concerns with ‘sexual goings-on’” (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950, p. 250) and sexual repression (Sidanius, 1985) as defining features of right-wing orientations. In contrast, contemporary researchers have typically operationalized conservatism and authoritarianism with regard to an adherence to conformity to tradition, respect for authority, and aggression against norm-violators (Altemeyer, 1996) or to the general acceptance of inequality and the status quo (Jost, Fitzsimmons, & Kay, 2004). Religious fundamentalism in turn is “viewed as a religious manifestation of right-wing authoritarianism” (Altemeyer, 1996, p. 161). Such theoretical positions have de-emphasized sexual preoccupation as a defining quality of the right, presumably due, in part, to the historical difficulty with assessing private sexual lives. But the notion that sexual interests and preoccupations are correlates of conservatism and religiosity holds theoretical appeal that can now be revisited with the advent of new internet-search technologies.

The notion that the ideological right is drawn to sex is an outgrowth of earlier psychoanalytic theories (e.g., Freud, 1936) where those advocating against or opposing lifestyles and behaviors are at some level drawn to those behaviors. Religiosity and conservatism, as noted above, are defined by the support of tradition and convention and are typically associated with opposition to non-traditional sexual attitudes and behaviors. However, according to psychoanalytic theories, sexual urges, even non-traditional sexual urges, are natural and instinctual. Resisting open sexuality, therefore, may be viewed as repressing or suppressing sexual desires. Theoretically, those living in relatively conservative environments publically suppress their sexual desires, in keeping with right-wing ideology, but may privately indulge them. Given our interest in the very private (and largely anonymous) sexual activity of people on the internet in conservative contexts, our focus concerns an examination of the preoccupation hypothesis at the state level. That is, we examine aggregated and anonymized personal internet activity searches, to determine whether these activities at the state level correlate with the prevalence of conservatism and religiosity at the state level.

Indeed, recent evidence supports this possibility. For example, higher teen birth-rates have been observed in U.S. states with higher levels of religiosity, even after controlling for abortion rates and income (Strayhorn & Strayhorn, 2009). At .73, the correlation between religiosity and teen birth-rate astonished even the researchers, with teens in more religious states paradoxically engaging in more premarital unprotected sex. Closer to our interests, Edelman (2009) found that in U.S. states with more traditional positions on sexuality, gender, and religion more subscriptions to online pornography services are purchased. Supporting a positive association between religiosity/conservatism and a preoccupation with sex, Edelman’s analysis was notably restricted to those willing to purchase pornography via credit card (an activity leaving a permanent data-trail on credit card statements). Yet, the majority of online sexual content is free of cost and can be searched for discreetly via internet search engines. Whereas credit card purchase measures are permanent and represent socially damning commitment to a product/service, basic internet searches for sexual content are conducted with relative privacy and with easy access, ideal for measuring a more natural (and “risk-free”) preoccupation with sex.

For this purpose, Google Trends represents a specialized tool allowing users to enter a particular search term and explore popular interest in the term by providing a numerical score representing Google search volume for the term. Internet use in the U.S. is now very common, with considerable access from home (65 %) or elsewhere (38 %) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010b) and with Google the most used search engine (Alexa Internet Inc., 2013). Individualized search records are not publically available, but Google Trends allows researchers to tap Americans’ natural interests in and proclivities toward sexual content at an anonymized, state-level of analysis. Thus, although searching for sex on the internet represents a relatively private, anonymous activity, this new tool provides unique and novel insights into the private lives of Americans, aggregated at the state level, in ways previously impossible. Such a tool allows insights into sex-relevant search behaviors in a way not possible historically.

We examined the prevalence of U.S. state-level religiosity and state-level conservatism as predictors of searches for sex online. We examined both general text and image searches for sex plus general searches for specific sexual content (e.g., porn, gay sex). In keeping with earlier conceptions of the political right (Adorno et al., 1950; Sidanius, 1985) and the preoccupation hypothesis in particular, we predicted that greater levels of state religiosity or conservatism would be associated with increased searches for sexual content aggregated at the state level (for privacy). To be clear, this research question represents an analysis at the aggregate-level. A caveat is in order regarding our use of aggregate-level data, given that aggregate-level correlations are not equivalent to individual-level correlations (Hofstede, 1980; Kingston & Malamuth, 2011; Robinson, 1950; Zimring, 2006). Correlations involving aggregate-level data can be independent of relations observed at the individual-level (Forbes, 1997, 2004; Robinson, 1950; Strayhorn & Strayhorn, 2009). As such, aggregate data should not be extrapolated to individual behavior, particularly in the field of sex research, where sensitive topics are often examined. Consider a situation where inaccurate conclusions are drawn about individuals (e.g., rape victims, sex offenders) from aggregate data (see Kingston & Malamuth, 2011), an error which could have serious consequences. Aggregate data are useful, however, in providing insights when individual-level data are not available and/or in the interest of examining higher-levels of analysis (Subramanian, Jones, Kaddour, & Krieger, 2009). Using analyses aggregated at the state-level provides insights into the preponderance of qualities (e.g., locations relatively higher or lower in conservatism) within contextual domains, such as when examining whether states characterized by greater conservatism have fewer patents granted (McCann, 2011a) or more state executions (McCann, 2008), or whether immigrants from more negatively-stigmatized nations commit more suicides in the new host country (Mullen & Smyth, 2004). In keeping with the cautions noted above, readers are encouraged to interpret the results of the current examination at the state- rather than individual- level. As such, these analyses reflect an understanding of whether higher proportions of conservatism or religiosity in a state correlate with individual internet search habits aggregated at the state level (given ethical and legal constraints concerning personal information).

Method

We obtained publically available measures of state religiosity, conservatism, and sex-related Google search volume, as well as potentially relevant control variables commonly used in studies examining aggregate data: state population, gross domestic product (GDP), poverty rate, and internet use (e.g., Edelman, 2009; Schaller & Murray, 2008; Strayhorn & Strayhorn, 2009). Based on these publically available data, each state was assigned a score on each variable. We examined zero-order correlations between (1) state religiosity and sex-related Google search volume and (2) state conservatism and sex-related Google search volume. We then examined partial correlations controlling for population, GDP, poverty rate, internet use, and finally, conservatism or religiosity, respectively.

Measures

Sex-Related Google Search Volume

Google Trends reports the relative volume of searches entered into Google, calculating the number of searches conducted for a particular term relative to the total number of Google searches conducted. Upon entering a search-term (e.g., sex), and specifying a time (e.g., 2011) and location (e.g., Connecticut), Google Trends calculates the volume of searches for the term during that particular interval in that particular location on a scale ranging from 0 (lowest search volume) to 100 (highest search volume). Thus, when considering state-level Google searches, this score is derived by computing the number of Google searches for a specific term within a given state during a given time period relative to all Google searches conducted in that specific state during that interval. This index is computed for all states; the state with the highest search index is assigned a score of 100, with all other states scored relative to this highest-scoring state. Critically, search volume scores from differing locations (e.g., states) can be directly compared because data are normalized based on total Google search traffic within a respective location (see http://support.google.com/trends/). Therefore, one can directly compare searches for a specific term in California (large state population) with that term in Rhode Island (relatively smaller population), given that the Google Trends index has normalized the data to accommodate for internet traffic within states. This tool represents a valid means of tapping and comparing public interest in particular search-terms (Schietle, 2011).

Using Google trends, we obtained the search volume of 7 sex-related terms within the 50 United States. Because Google Trends substantially improved its geo-location algorithms on January 1, 2011 (see http://support.google.com/trends/answer/1383240?hl=en), we began our search here, examining 2011 and 2012 searches for general web search terms “sex,” “gay sex,” “porn,” “xxx.”, “free porn,” “gay porn,” and the Image search term “sex” (i.e., searching for the term “sex” within the Google Image search subdomain, which returns only images as results).

Religiosity

The percentages of “very religious” individuals within each state in 2011 and the percentage of individuals within each state considering religion an important part of their daily lives in 2009 were obtained from Gallup (2013). Gallup conducts telephone surveys, randomly sampling from the U.S. population using random-digit-dialing. The percentage of very religious individuals within each state was obtained from a random sample of 353,492 U.S. adults and the percentage of individuals within each state considering religion an important part of their daily lives was obtained from a random sample of 355,334 U.S. adults. These two items (r = .96) were averaged into an index of state religiosity.

Conservatism

The percentage of self-identified conservative individuals within each state (i.e., those describing their political views as conservative) in 2011 was obtained from Gallup (2013). This item was obtained based on a random sample of 353,492 U.S. adults.

Population

State population (in 2010) came from the U.S. Census Bureau (2010a). The census involves the actual enumeration of people in the U.S., with people contacted by mail or in person. Details are provided at http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/wc_dec.xhtml.

GDP

The 2009 current-dollars GDP for each state came from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (2011). The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis employs an 8-step procedure to estimate GDP by state; a fuller description of the procedure is available at http://www.bea.gov/regional/docs/product/methods.cfm.

Poverty

The 2009 percentage of individuals within each state below the poverty level in the preceding 12 months came from the U.S. Census Bureau (2009). Specifically, data were obtained from the 2009 American Community Survey (ACS), administered by mail, by phone, or in person. The 2009 sample size for the ACS was 146,716. Details are provided at http://www.census.gov/acs/www/methodology/methodology_main/

Internet Use

The 2010 percentages of individuals within each state accessing the internet at home and outside the home were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau (2010b). Specifically, data were obtained from the 2010 Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS is administered by phone or in person. A probability sample of approximately 60,000 households is used. Details are provided at http://www.census.gov/cps/methodology/.

Results

Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1. It can be seen that a few outliers were present in the data. All correlations involving variables with an outlier were conducted with and without the outliers, with no significant differences in results observed, so results are reported with all cases included. As noted above, state population, GDP, poverty rate, and internet use were considered as control variables. Each of these control variables was associated with at least 5 of the 7 sex-related Google searches examined for each year (r s = |.28| to |.69|, p s < .05). Thus, these variables were determined to be reasonable covariates.

Associations Between State-Level Religiosity and Sex-Related Google Searches

At the zero-order level, increased state religiosity was associated with increased Google searching for sex, gay sex, and gay porn in 2011 (see Table 2). After controlling for demographic variables and internet use, state religiosity was significantly associated with increased 2011 Google searching for sex. When state conservatism was added as an additional covariate (given that religiosity and conservatism correlated at .80, p < .001), this association remained significant (r p = .33). The pattern was largely replicated for 2012: increased state religiosity was significantly associated with increased searches for sex, gay sex, porn, free porn, and gay porn at the zero-order level. After controlling for demographic variables and internet use, and after also controlling for state conservatism, state religiosity was still positively associated with searching for sex (r p = .36), but not with searching for gay sex, porn, free porn, or gay porn. Interestingly, the association between state religiosity and searching for sex images became significantly negative upon controlling for demographic variables, internet use, and state conservatism (see Table 2). Overall, a reliable positive association of moderate-to-large association size (Cohen, 1988, pp. 79–81) exists between state-level religiosity and searches for the term “sex.” Scatterplots depicting this relation for 2011 and 2012 (including state placement around regression line) are provided in Figs. 1 and 2.

Associations Between State-Level Conservatism and Sex-Related Google Searches

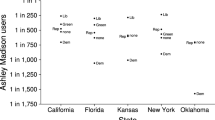

At the zero-order level, increased state conservatism was associated with increased Google searching for sex, gay sex, and sex images in 2011 (see Table 2). After controlling for demographic variables and internet use, these correlations remained significant, with the exception of the association between state conservatism and increased Google searching for gay sex. Upon adding state religiosity as a covariate, only the association between state conservatism and searching for sex images remained significant (r p = .55). These patterns replicated for 2012 Google searches: positive zero-order correlations were observed between state conservatism and searches for sex, gay sex, and sex images. After controlling for demographic variables and internet use, state conservatism was only significantly associated with searching for gay sex and searching for sex images, with the latter remaining significant after additionally controlling for state religiosity (r p = .45). Thus, whereas a reliable positive association exists between state religiosity and searches for sex as a general search term, a similarly reliable association between state conservatism and searches for sex images was observed and replicated across two time periods. Scatterplots depicting this relation for 2011 and 2012 (including state placement around regression line) are provided in Figs. 3 and 4.

Ancillary Analyses

As noted above, state religiosity and conservatism were highly correlated. Thus, in addition to the analyses reported above, we also examined associations between a state religiosity-conservatism composite score (obtained by computing the mean of the two variables) and sex-related Google searches. At the zero-order level, higher scores on the composite variable were associated with increased Google searching for sex, gay sex, and sex images in 2011 (see Table 2). After controlling for demographic variables and internet use, only the associations with Google searching for sex and sex images remained significant. For 2012 Google searches, higher scores on the composite variable were associated with increased Google searching for sex, gay sex, porn, free porn, gay porn, and sex images at the zero-order level. After controlling for demographic variables and internet use, the pattern observed for 2011 Google searches was replicated: only associations between state religiosity-conservatism and Google searching for sex and sex images remained significant.

Discussion

State-level religiosity was associated with increased general web searching for sex content, even after controlling for demographic variables. Specifically, American states with a greater proportion of those considering themselves very religious and considering religion an important factor in life demonstrated more active searches for sexual content (generally), representing a moderate association size (Cohen, 1988, pp. 79–81). The greater the proportion of conservatives per state, the increased image-specific sex searches, with partial-correlations ranging from .45 to .55. These results become particularly compelling when considered in terms of a binomial association size display: a .50 correlation, for instance, means that among states above the median (i.e., in the top half) in the proportion of conservatives per state, 75 % were also above the median in behaviorally searching for sex images online. Knowing a state’s proportion of conservative citizenry, therefore, is a very meaningful and strong predictor of the magnitude of searching for sexual images on the internet. These results, observed across two separate years, were consistent with the preoccupation hypothesis that American religiosity and conservatism are associated with an increased (not decreased) interest in sexual content. State-level religiosity was not associated with increased searching for non-traditional sex per se (e.g., sexual imagery, pornography), but rather searching for sex in general. It may be that these “sex” searches were conducted with the intention of delivering “traditional” sexual content (e.g., information regarding monogamous, married, heterosexual sex). Indeed, state-level religiosity was negatively associated with a more non-traditional search, the search for sexual imagery. On the other hand, state-level conservatism was associated with increased searching specifically for sexual images, representing an interest in actually viewing sexually explicit material (largely free of text or information). Thus, results pertaining to state-level conservatism were most consistent with the preoccupation hypothesis.

These internet search findings were consistent with a recent article in the New York Times (“Strip clubs in Tampa are ready to cash in on G.O.P. convention”) where a strip-club owners’ organization claimed that, during political conventions, those on the political right (vs. left) spend considerably more money ($150 vs. $50 per person) at exotic strip clubs (Alvarez, 2012). A recent documentary further elaborates this point (see de Guerre, 2013). For instance, Jim Kleinhans (president of 2001 Odyssey, one of Tampa’s most well-known and frequented strip clubs) observed that strip clubs generally yield three times more revenue during the Republican National Convention (RNC) than during the Super Bowl, an already high-grossing event.Footnote 1 During the RNC convention, escorts and exotic dancers apparently “flock” to the host city to capitalize on this increased demand for sexual entertainment. In the words of Layla Love, an exotic dancer at 2001 Odyssey, “Since the RNC has started, I have actually started to do 15 to 17 h shifts, every day, until the convention is over. So, for basically 7 days straight, I will be in the club, every day, day shift and night shift.” Of course, these anecdotal accounts may be influenced by political, economic or public relations motivations. Nonetheless, the current results were in accordance with these accounts as well as well-publicized prominent anecdotal examples (see “Introduction”). This analysis provides scientific evidence of reliable, moderate-to-large associations (Cohen, 1988, pp. 79–81) consistent with the hypothesis that there is enhanced interest in sexuality in locations with greater proportions of those on the right (vs. left).

It is important to keep in mind that these differences reflect relative (not absolute) differences. We do not imply that ideological liberalism is associated with a lack of interest in sex. On the contrary, the political left is associated with support for more non-traditional sexual values (e.g., Carroll et al., 2008; Sakalh-Uğurlu & Glick, 2003; Sherkat & Ellison, 1997), and prominent examples of sexuality and promiscuity on the left are evident (consider Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky). Our findings, however, were congruent with the preoccupation hypothesis: although characterized by an outward and vocal opposition to sexual freedom, regions characterized by stronger political right orientations were relatively associated with a greater underlying attraction to sexual content. Employing a novel methodology and focusing on the relatively private and anonymous seeking of sexual content online, our results were in keeping with scientific research in related domains (e.g., Edelman, 2009; Strayhorn & Strayhorn, 2009). Collectively, these findings run counter to lay conceptions about political ideology and sexual behavior and represent interesting, meaningful, and frequently replicated associations. Such contradictions provide unique and valuable insights into human nature generally. For instance, consider the reliable, positive associations between religious identification, extrinsic religiosity, or fundamentalism and increased racial prejudice (see the meta-analysis by Hall, Matz, & Wood, 2010). Clearly, people fail to “practice what they preach.” It is clear that, for socially-sensitive issues such as sexuality, behavioral measures are critical in order to tap real-life activity within a charged political context. This argument becomes all the more relevant to the extent that people find themselves in particularly conservative environments (as captured by our use of aggregate data). Exposing people to overheard conservative (vs. permissive) sexual norms, for instance, leads even university-aged participants to self-report more traditional sexual behaviors (e.g., older age of first sexual encounter; more monogamy) (see Fisher, 2009). Finding oneself in a context or region with more conservative social norms, therefore, appears to diminish admissions of sexual interests and behaviors, making relatively private behaviors, such as internet searches, particularly valuable and meaningful, particularly for our research question.

The use of internet search data offers very rich and meaningful insights into the largely private lives of Americans, revealing their natural interests. By necessity, the data were aggregated at the state level to ensure the very anonymity critical for addressing this “private life” question. We examined the private lives of the political left versus right at the state-level, satisfying a call by others to depart from focusing solely on individual-level associations and also examined research questions at higher levels of analysis (Subramanian et al., 2009). Of course, it would be ideal to examine these associations at both the individual and state-level, especially given that individual- and state-level associations can vary (e.g., see Forbes, 1997, 2004; Robinson, 1950). However, individual data on Google search volume are not available. Such data would compromise anonymity, a critical factor in this examination. Given current controversies surrounding individual data tracking (Greenwald & MacAskill, 2013), aggregate data represent a less threatening and more ethical means by which to examine these associations. These findings add to a growing literature employing region-level data to examine, for instance, associations between state-level conservatism and state laws pertaining to homosexuality (McCann, 2011b), state-level conservatism and state death penalty sentencing (McCann, 2008), and, outside of the ideology domain, associations between cultural differences (e.g., in personality factors such as openness or extraversion) and disease prevalence (Murray & Schaller, 2010; Schaller & Murray, 2008). Our findings also add to the growing interest in the “secret lives” of the political left versus right, such as examining bedrooms and work offices for the number of (and type of) books and music owned (Carney, Jost, Gosling, & Potter, 2008; Jost, Nosek, & Gosling, 2008).

Of course, our investigation had limitations. Our examination was limited to internet users, a very large but not complete sample of citizens (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010b). Further, our examination concerned religiosity/conservatism in the United States, a primarily Christian nation, with a highly polarized left–right political divide. It remains an open question whether similar associations exist outside of the American context. Finally, an alternative interpretation of our results exists: it is possible that liberal citizens living in states higher in religiosity or conservatism search more for sexual content due to living in a more sexually-restricted environment. Yet, our interpretation was consistent with first-hand accounts from those directly working in the sex-industry (see above).

To be clear, our interest concerns the seeking of, rather than consuming of, online sexual content (cf. Edelman, 2009). Internet searches reflect the purposeful seeking of and naturalistic interest in sexual content, particularly suiting our research objective. The observed associations between state-level religiosity or conservatism and seeking out online sexual content were psychologically interesting given conservative U.S. politicians’ recent calls, presumably bowing to constituent pressure, to ban/censor sexual material on the internet (e.g., see Owens, 2012). Such bans might paradoxically represent attempts to stifle or deny interest in sexually explicit material. At minimum, these internet-search data clearly demonstrate that those living in states with greater proportions of very religious or conservative citizenry nonetheless seek out and experience the forbidden fruit of sexuality in private settings. These paradoxical insights challenge commonly held assumptions and stereotypes, providing a springboard for research into the anonymized private lives of citizens as a function of political context.

Notes

Conservatives overwhelming vote (and identify themselves as) Republicans (Jost, 2006). Further, when examining associations between the percentage of self-identified Republicans in each state in 2011 (obtained from Gallup, 2013) and sex-related Google-searches, results were largely equivalent to those observed when associations with state-level conservatism were examined. Upon controlling for demographic variables and state-level religiosity, greater Republican citizenry was associated with increased searching for sex images in both 2011 (r = .60, p < .001) and 2012 (r = .50, p < .001).

References

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Harper.

Alexa Internet Inc. (2013). Statistics summary for google.com. Retrieved December 20, 2012, from http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/google.com.

Altemeyer, B. (1996). The authoritarian specter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Alvarez, L. (2012). Strip clubs in Tampa are ready to cash in on G.O.P. convention. The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2013, from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/27/us/strip-clubs-in-tampa-are-ready-to-cash-in-on-gop-convention.html?_r=0.

Carney, D. R., Jost, J. T., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2008). The secret lives of liberals and conservatives: Personality profiles, interaction styles, and the things they leave behind. Political Psychology, 29, 807–840. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00668.x.

Carroll, J. S., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Nelson, L. J., Olson, C. D., McNamara-Barry, C., & Madsen, S. D. (2008). Generation XXX: Pornography acceptance and use among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23, 6–30. doi:10.1177/0743558407306348.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

de Guerre, M. (Writer, Director, Producer, 2013).Why men cheat [Television series episode]. CBC Doczone. Ontario, Canada: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Available from http://www.cbc.ca/doczone/episode/why-men-cheat.html.

Edelman, B. (2009). Red light states: Who buys online adult entertainment? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23, 209–220. doi:10.1257/jep.23.1.209.

Fisher, T. D. (2009). The impact of socially conveyed norms on the reporting of sexual behavior and attitudes by men and women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 567–572. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.007.

Fisher, R. D., Cook, I. J., & Shirkey, E. C. (1994). Correlates of support for censorship of sexual, sexually violent, and violent media. Journal of Sex Research, 31, 229–240. doi:10.1080/00224499409551756.

Forbes, H. D. (1997). Ethic conflict: Commerce, culture, and the contact hypothesis. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Forbes, H. D. (2004). Ethnic conflict and the contact hypothesis. In Y. T. Lee, C. McAuley, F. Moghaddam, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The psychology of ethnic and cultural conflict (pp. 69–88). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Freud, A. (1936). The ego and mechanisms of defense. New York: Hogarth.

Gallup, Inc. (2013). State of the states. Retrieved January 28, 2013, from www.gallup.com/poll/125066/state-states.aspx.

Greenwald, G., & MacAskill, E. (2013). NSA Prism program taps into user data of Apple, Google, and others. The Guardian. Retrieved July 01, 2013, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/jun/06/us-tech-giants-nsa-data.

Hall, D. L., Matz, D. C., & Wood, W. (2010). Why don’t we practice what we preach? A meta-analytic review of religious racism. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14, 126–139. doi:10.1177/1088868309352179.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hunsberger, B., & Jackson, L. M. (2005). Religion, meaning, and prejudice. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 807–826. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00433.x.

Jost, J. T. (2006). The end of the end of ideology. American Psychologist, 61, 651–670. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.651.

Jost, J. T., Fitzsimons, G., & Kay, A. C. (2004). The ideological animal: A system justification view. In J. Greenberg, S. L. Koole, & T. Pyszczynski (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 263–282). New York: Guilford.

Jost, J. T., Nosek, B. A., & Gosling, S. D. (2008). Ideology: Its resurgence in social, personality, and political psychology. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 126–136. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00070.x.

Kingston, D. A., & Malamuth, N. M. (2011). Problems with aggregate data and the importance of individual differences in the study of pornography and sexual aggression: Comment on Diamond, Jozifkova, and Weiss (2010). Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 1045–1048. doi:10.1007/s10508-011-9743-3.

Koenig, H. G., McCullough, M. E., & Larson, D. B. (2001). (Eds.). Handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press.

McCann, S. J. H. (2008). Societal threat, authoritarianism, conservatism, and U.S. state death penalty sentencing (1977–2004). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 913–923. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.913.

McCann, S. J. H. (2011a). Conservatism, openness, and creativity: Patents granted to residents of American states. Creativity Research Journal, 23, 339–345. doi:10.1080/10400419.2011.621831.

McCann, S. J. H. (2011b). Do state laws concerning homosexuals reflect the pre-eminence of conservative-liberal individual differences? Journal of Social Psychology, 151, 227–239.

Mullen, B., & Smyth, J. M. (2004). Immigrants suicide rates as a function of ethnophaulisms: Hate speech predicts death. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66, 343–348. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000126197.59447.b3.

Murray, D. R., & Schaller, M. (2010). Historical prevalence of disease within 230 geopolitical regions: A tool for investigating origins of culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41, 99–108. doi:10.1177/0022022109349510.

Nagrav, N. (2010). Top anti-gay Christian activist and minister, George Alan Rekers, linked to gay escort. New York Daily News. Retrieved December 1, 2012, from http://www.nydailynews.com/news/national/top-anti-gay-christian-activist-minister-george-alan-rekers-linked-gay-escort-article-1.447171.

Nossiter, A. (2007). Senator apologizes again for prostitution link. The New York Times. Retrieved December 1, 2012, from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/17/us/17vitter.html.

Owens, L. (2012). Rick Santorum promises war on porn industry. The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 1, 2012, from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/16/rick-santorum-war-on-porn_n_1353383.html.

Robinson, W. S. (1950). Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. American Sociological Review, 15, 351–357. doi:10.2307/2087176.

Sakalh-Ugurlu, N., & Glick, P. (2003). Ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward women who engage in premarital sex in Turkey. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 296–302. doi:10.1080/00224490309552194.

Schaller, M., & Murray, D. M. (2008). Pathogens, personality, and culture: Disease prevalence predicts worldwide variability in sociosexuality, extraversion, and openness to experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 212–221. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.212.

Schietle, C. P. (2011). Google’s insights for search: A note evaluating the use of search engine data in social research. Social Science Quarterly, 92, 285–295. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00768.x.

Sherkat, D., & Ellison, C. (1997). The cognitive structure of a moral crusade: Conservative Protestantism and opposition to pornography. Social Forces, 75, 957–982. doi:10.2307/2580526.

Sidanius, J. (1985). Cognitive functioning and sociopolitical ideology revisited. Political Psychology, 6, 637–661. doi:10.2307/3791021.

Strayhorn, J. M., & Strayhorn, J. C. (2009). Religiosity and teen birth rate in the United States. Reproductive Health, 6(1), 14. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-6-14.

Subramanian, S. V., Jones, K., Kaddour, A., & Krieger, N. (2009). Revisiting Robinson: The perils of individualistic and ecologic fallacy. International Journal of Epidemiology, 38, 342–360. doi:10.1093/ije/dyn359.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. (2011). Gross domestic product by state. Retrieved January 28, 2013, from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/income_expenditures_poverty_wealth/gross_domestic_product_gdp.html.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2009). American community survey: Poverty status in the past 12 months by sex and age. Retrieved January 28, 2013, from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/income_expenditures_poverty_wealth/income_and_poverty-state_and_local_data.html.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010a). State resident population by age and sex: 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2013, from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/population/estimates_and_projections-states_metropolitan_areas_cities.html.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010b). Reported internet usage for individuals 3 years and older, by state: 2010. Retrieved January 28, 2013, from http://www.census.gov/hhes/computer/publications/2010.html.

Whitley, B. E. (1999). Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 126–134. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.126.

Zimring, F. E. (2006). The great American crime decline. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

MacInnis, C.C., Hodson, G. Do American States with More Religious or Conservative Populations Search More for Sexual Content on Google?. Arch Sex Behav 44, 137–147 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0361-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0361-8