Abstract

To improve our understanding of the bright side and the dark side of political ties and determine the processes linking political ties to firm performance in emerging markets, we investigate the underlying mechanism of political ties’ effects from the perspective of dynamic capability theory and institutional theory. We posit that reduced market-focused innovation capability and strengthened legitimacy mediate the effect of political ties on firm performance. In addition, to capture the nature of the relationship between political ties and performance, we adopt a contingency perspective in our examination of the moderating roles of legal enforceability and competitive intensity. Specifically, we suggest that legal enforceability buffers the negative impact of political ties on market-focused innovation capability but mitigates the positive impact of political ties on firm legitimacy. Moreover, competitive intensity enhances the positive impact of market-focused innovation capability and firm legitimacy on firm performance. We test our hypotheses using a survey with 362 respondents in China. In conclusion, our findings provide important insights into how Chinese firms effectively utilize political ties to improve their performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Building political ties is a prevalent marketing strategy in emerging markets (Heirati & O’Cass, 2016; Ismail Jr et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2014). Many scholars have examined the use and results of this strategy by testing the impact of political ties on firm performance, and they have reached a consensus that political ties constitute a double-edged sword with respect to firm performance. That is, political ties have the potential to improve performance (Peng & Luo, 2000; Peng & Zhou, 2005; Zhou et al., 2014) but also run the risk of eroding performance (Chen & Wu, 2011; Hadani & Schuler, 2013; Li & Sheng, 2011; Li, Zhou, & Shao, 2009). To provide insights to help firms exploit political ties, scholars have further examined the boundary conditions of the impacts of political ties on firm performance. For example, Sheng, Zhou, and Li (2011) found that political ties lead to greater performance when government support is weak and technological turbulence is low, and Zhang, Tan, and Wong (2015) indicated that the effect of political ties on firm performance is contingent upon firms’ choice of innovation activities to pursue.

Understanding how political ties are connected to performance can also help firms effectively use these ties. With such an understanding, firms may use political ties more effectively by keeping a watchful eye on the mediators of the political ties-performance nexus. However, based on a comprehensive literature review (see Table 1), we find that research on the underlying mechanism of the link between political ties and performance is still nascent. Specifically, from the perspective of dynamic capability theory and transaction costs economics, research indicates that political ties facilitate performance by improving firms’ adaptive capability and reducing transaction costs (Gu, Hung, & Tse, 2008; Lu et al., 2010; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017), but there is no research (with the exception of Guo, Xu, & Jacobs, 2014) integrating institutional theory to test the mediating effect of legitimacy on the political ties-performance nexus. More importantly, most studies have focused on the mediators of the positive impact of political ties on performance but neglected the mediators that can explain why political ties erode firm performance.

To fill these research gaps, we investigate the underlying mechanism of both sides of the effect of political ties by integrating dynamic capability theory and institutional theory. Specifically, we simultaneously examine the mediating effects of market-focused innovation capability and legitimacy on the impacts of political ties on performance. We posit that on the one hand, political ties facilitate a firm’s legitimacy, which in turn increases its performance; on the other hand, political ties inhibit a firm’s market-focused innovation capability and erode its performance.

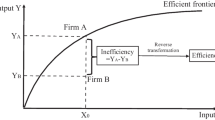

To fully map the dual effects of political ties, we also consider the moderating mediation of institutional and market factors. In particular, we posit that legal enforceability, which refers to the perceived legal protection of a company’s financial interests in a business transaction (Cai, Jun, & Yang, 2010; Luo, 2007; Zhou & Poppo, 2010; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017), buffers the negative effect of political ties on innovation capability but mitigates the positive effect of political ties on legitimacy. In addition, competitive intensity enhances the positive impacts of market-focused innovation capability and firm legitimacy on firm performance. Figure 1 shows the conceptual model. Based on a survey completed by 362 respondents in China, most of our hypotheses are supported.

Conceptual framework

Political ties refer to the extent to which managers cultivate interpersonal relations with government officials at various levels of administration and regulatory organizations, such as tax bureaus and commercial administration bureaus (Peng & Luo, 2000; Sheng, Zhou, & Li, 2011). In emerging economies such as China, underdeveloped legal frameworks and pervasive institutional transitions necessitate a strategy centered on developing political ties (Guo, Xu, & Jacobs, 2014; Ismail Jr et al., 2013; Li, Zhou, & Shao, 2009; Peng & Luo, 2000). However, in previous empirical works, the reported effects of political ties on firm performance are contradictory (Li, Poppo, & Zhou, 2008; Wang et al., 2013). To reconcile the mixed results, some researchers have suggested that the value of political ties may be contingent on important contextual factors (Wang et al., 2013; Wu & Chen, 2012; Zhou et al., 2014). For example, Li, Poppo, and Zhou (2008) found that political ties increase domestic firms’ performance but decrease the profitability of foreign firms in China. Peng and Luo (2000) pointed out that the impact of political ties on firm performance is stronger for firms in low-growth industries than for firms in high-growth industries. Sheng, Zhou, and Li (2011) suggested that government support negatively moderates the relationship between political ties and firm performance.

However, new advances in research on political ties suggest that political ties are not very likely to convert directly into performance. Converting mechanisms for explaining how managerial ties are materialized into performance have attracted increasing attention (Guo, Xu, & Jacobs, 2014; Wang et al., 2013; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017). For example, recently examined mediators include firm capabilities (Gu, Hung, & Tse, 2008; Lu et al., 2010; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017), resource acquisition (Wang et al., 2013), and institutional advantage (Li & Zhou, 2010). These reports enrich our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the relationship between political ties and performance but merely focus on the bright side of political ties. In fact, an increasing number of studies have pointed out that political ties are not always beneficial to firm performance (Gu, Hung, & Tse, 2008; Li, Poppo, & Zhou, 2008). For instance, some studies have indicated negative effects of political ties on innovation capability (Wu, 2011; Yu et al., 2016), but the mediating effect of innovation capability on the relationship between political ties and performance has seldom been examined in the extant literature.

Further, using institutional theory, scholars have provided insights into how political ties work to improve performance from the perspective of legitimacy (Guo, Xu, & Jacobs, 2014; Peng & Luo, 2000; Sheng, Zhou, & Li, 2011; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017). However, scant research examines the mediating effect of legitimacy on the political ties-performance nexus. Thus, to fill these gaps in the literature, we integrate dynamic capability theory and institutional theory to discuss the dual effect of political ties on performance.

The mediating effects of market-focused innovation capability

Innovation capability refers to a firm’s ability to integrate key capabilities and resources to successfully stimulate innovation, and it is a key driver of sustainable competitive advantage (Zhou, Gao, & Zhao, 2017). Innovation capability enables firms to cope with environmental changes and improve their performance during different phases of the business cycle, especially in today’s fast-changing environment (Jiménez-Jiménez & Sanz-Valle, 2011; Zhou, Gao, & Zhao, 2017). The innovation literature finds that innovation capability occurs in innovation processes, which include technique-focused innovation capability and market-focused innovation capability (Damanpour, Walker, & Avellaneda, 2009; Foroudi et al., 2016).

Market-focused innovation capability refers to the competence to apply collective knowledge, skills, and resources to innovation activities to adapt to changes in customer demand and create added value for customers (Hogan et al., 2011). Firms with higher market-focused innovation capability can more easily address the changing demands of their clients and are better able to exploit new market opportunities (Jansen, Bosch, & Volberda, 2006; Sorensen & Stuart, 2000). Consequently, market-focused innovation capability can help a firm attain superior performance by obtaining a greater market share and/or customer loyalty (Hogan et al., 2011; Ngo & O'Cass, 2013).

However, market-focused innovation capability may be negatively affected by political ties. First, firms benefiting from political ties are likely to lack incentives to develop market-focused innovation capability due to the path-dependence effect. For these firms, previous benefits from political ties enhance managers’ confidence in their political ties and encourage them to reinvest in building and maintaining their relationships with government officials rather than adapting to customers’ changing demand (Chen & Wu, 2011; Wu, 2011). A historical path usually also fosters a vested interest group that may include key firm managers (Greve & Seidel, 2015). They may block the transformation of their profit model from political ties to market demand because it may challenge the perceived benefits.

Second, firms relying on political ties are likely not to have an appropriate culture to foster market-focused innovation capability. Market orientation refers to an organizational culture facilitating market-focused innovation capability (Zhou, Yim, & Tse, 2005). A firm with market orientation can obtain the necessary intelligence from its target customers and competitors (which in turn leads to a better understanding of customer preference changes and competitor strategic moves) and thus foster its market-focused innovation capability (Laforet, 2008). However, firms relying on political ties prefer to accommodate or yield to the government’s goals. An orientation towards the government instead of towards the market impedes a firm’s efficiency in responding to market change and in turn suppresses the firm’s market-focused innovation capability.

Third, firms relying on political ties are likely to lack the necessary resources to develop market-focused innovation capability. Building and maintaining political ties likely consumes a firm’s internal resources. For example, a firm may spend time and financial resources to engage in fulfilling politically oriented goals (e.g., increasing employment levels) (Li, Zhou, & Shao, 2009; Sheng, Zhou, & Li, 2011). Even worse, firms must offer money or other forms of compensation to obtain key resources and favorable treatment from their government (Li, Zhou, & Shao, 2009; Wu, 2011). Thus, in a limited resource setting, efforts devoted to developing political ties compete with time and resources devoted to tracking market demand (Zhang, Tan, & Wong, 2015) and in turn impede the improvement of market-focused innovation capability.

We therefore propose that political ties have a negative effect on firm performance by eroding market-focused innovation capability.

-

H1 Market-focused innovation capability has a negative mediating effect on the link between political ties and firm performance.

The mediating effects of legitimacy

Legitimacy is “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman, 1995). There are two elements of legitimacy that can influence the beholders’ support for a firm, namely, pragmatic legitimacy and moral legitimacy (Handelman & Arnold, 1999). Pragmatic legitimacy rests on the self-interested calculations of a firm’s direct stakeholders (Suchman, 1995), such as customers, suppliers, distributors, and shareholders. As long as firm stakeholders perceive that the firm’s actions increase their own welfare, the firm obtains pragmatic legitimacy (Handelman & Arnold, 1999). In return, a firm with pragmatic legitimacy has a greater market share and revenue because of customer satisfaction and identification, and it also has fewer financial, production and transaction costs since it obtains its partners’ trust and cooperation (Suchman, 1995; Wu, 2011).

Moral legitimacy refers to beholders’ positive normative evaluation of a firm based on the firm’s actions taken to increase the welfare of the community and society (Suchman, 1995), such as donations, environmental protection, and poverty relief. Unlike pragmatic legitimacy, moral legitimacy rests on a judgment derived from altruistic motivation, so a firm with moral legitimacy can obtain more word-of-mouth references and suffer fewer boycotts in the case of a critical incident. In general, legitimacy can improve firm performance by increasing revenue, cutting costs, and avoiding risk.

In terms of the type of beholder, Dacin, Oliver, and Roy (2007) distinguish legitimacy into four dimensions: relational legitimacy, social legitimacy, market legitimacy and investment legitimacy. “Firms that are perceived as attractive and capable partners accrue relational legitimacy” (Dacin, Oliver, & Roy, 2007). This means that a firm with higher relational legitimacy is regarded as a high-quality partner by other firms. Thus, relational legitimacy may improve firm performance by reducing transaction costs with other firms. Social legitimacy is linked to corporate social responsibility. Firms with social legitimacy are expected to conform to societal rules, such as providing quality-assured and safe products and employing resource-conserving and environmentally friendly strategies. Therefore, firms with social legitimacy may perform well because of their high moral legitimacy. Market legitimacy can be established through acquiring rights or qualifications to operate in a specific market and by ensuring endorsement and receptiveness from the government, customers, or suppliers (Dacin, Oliver, & Roy, 2007). This implies that a firm with market legitimacy should have legitimate operation licenses and a wealth of business experience in a specific market. A firm with higher market legitimacy is likely to enter more markets or to have the ability to obtain more orders, which results in higher performance. Investment legitimacy refers to “the worthiness of a firm’s business activities and strategic decision in the eyes of corporate investors, such as the parent firms’ board of directors, executives, venture capitalists and shareholders” (Dacin, Oliver, & Roy, 2007, P177, 3rd paragraph). With more confidence in a firm and its business activities, investors are more likely to reinvest in working capital and/or fixed assets; meanwhile, the recognition of strategic decisions by the board of directors and executives reduces firm decision costs. Lower financial costs and decision costs are both important factors for firm performance.

A firm can acquire legitimacy by networking with the government (Li et al., 2014; Peng & Luo, 2000) because political ties send beholders a signal that the firm has the ability and the motivation to satisfy their pragmatic and moral expectations. First, as mentioned, political ties can provide firms with access to scarce resources, information and preferential treatment (Li et al., 2014; Zhou & Li, 2007). Firms with these advantages are more likely to develop the ability to provide quality products and services at reasonable prices, which is consistent with customer welfare and satisfies customers’ pragmatic expectations. Second, for a firm’s investors, suppliers and distributors, political ties imply that the focal firm will likely help them obtain a superior return on their investment or avoid risk by means of key resources obtained from and protection by the government. The signal of improved welfare meets the pragmatic expectations of firm partners.

Third, improving the welfare of the community and society is an important task of the government, and the government often needs the help of firms to achieve these objectives. A firm with political ties usually has to accommodate the government’s demands, so the firm is more likely to participate in activities that benefit the public, thus satisfying its beholders’ moral expectations. For example, a firm with high levels of government ownership is expected to pursue corporate social responsibility in accordance with government policy, such as infrastructure development and the resolution of unemployment challenges (Li & Zhang, 2010).

In summary, due to the role the government plays in economic and social activities, political ties can enhance firm legitimacy by sending authoritative signals to beholders (including consumers, partners and the general public), which helps improve firm performance. Thus, H2 states the following:

-

H2 Legitimacy has a positive mediating effect on the link between political ties and firm performance.

Political ties have both a negative effect and a positive effect on firm performance through eroding innovation capability and fostering legitimacy, respectively; however, these dual effects depend on institutional and market contexts (Sheng, Zhou, & Li, 2011; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017). Thus, to enrich our understanding of the political ties-performance nexus and the mediating effects of innovation capability and legitimacy, we consider the contingent effects of institutional and market factors on the mediation.

Moderating effects of legal enforceability

Legal enforceability, which refers to the perceived legal protection of a company’s financial interests in a business transaction, is a reflection of the formality of laws and regulations, independent law enforcement, and the public’s cultural tradition and attitudes towards laws (Child, Chung, & Davies, 2003; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017). The problem of uneven legal enforceability between different regions is one of the most prominent features of emerging markets (Qian et al., 2017). Specifically, in China, where legal institutions are inadequate, firms find it difficult or expensive to follow normal legal processes to gain protection against ineffective punishments and unlawful or unfair competitive behaviors; thus, weak legal enforceability disrupts the economic order and fails to give firms adequate legal protection (Sheng, Zhou, & Li, 2011; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017).

We posit that weak legal enforceability increases the restraining effect of political ties on market-focused innovation capability for the following reasons. First, weak legal enforceability leads to an increase in government power in protecting a firm’s activities (Li, Zhou, & Shao, 2009; Zhou & Poppo, 2010). Under these circumstances, the pivotal role of political ties in helping firms attain adequate support, favorable policies and privileges that shelter them from unlawful behavior is strengthened (Peng & Luo, 2000; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017), which in turn reassures managers of their political ties. As a result, firms prefer to (re)invest more money or other resources in building and maintaining their relationship with the government rather than developing their market-focused innovation capability (Wu, 2011). At the same time, leveraging the political power of government officials enables firms to more easily safeguard potential victims of unlawful and unethical behaviors (Li et al., 2012), again reinforcing managers’ commitment to the status quo (Geletkanycz & Black, 2001). Thus, decision makers are more willing to forego investing in market-focused innovation capability in favor of strengthening their political ties with the government.

Second, government interventions in a business’s operations may decrease the costs of legal actions against unlawful behaviors in an environment with weak legal enforceability (Zhou, Gao, & Zhao, 2017; Zhou & Poppo, 2010). Thus, the greater their dependency on the government to gain access to supporting transactions and preventing unlawful competition, the more pressure firms face from the government (Chen & Wu, 2011; Warren, Dunfee, & Li, 2004). As a result, firms’ strategies are more likely to follow the commands and goals of the government, such as increased employment, fiscal health, regional development, and social stability. When political orientation rather than market orientation is likely to become a dominant culture, firms are challenged in developing their market-focused innovation capability. Consequently, we posit H3 as follows:

-

H3 The greater the degree of legal enforceability is, the weaker the negative effect of political ties on innovation capability.

Legal enforceability also decreases the positive impact of political ties on a firm’s legitimacy. Logically, legal enforceability relates to the degree to which the legal system can protect individual and organizational rights and how well it supports the effectiveness of contract enforcement (Peng & Zhou, 2005; Qian et al., 2017). When legal enforceability is high, it is not necessary for firms to obtain government protection with the aid of political ties. In general, legal enforceability depreciates political ties. Thus, in an environment with a high degree of legal enforceability, a firm’s direct stakeholders are less likely to believe that a firm with political ties is more competent in increasing their welfare; thus, political ties are not a major cause of pragmatic legitimacy.

In addition, efficient formal institutions limit government intervention in firm operations, even in a firm with political ties (Zhou, Gao, & Zhao, 2017). In deciding whether to engage in activities that benefit the public, a firm operating in an efficient formal institutional environment is likely to act based on its own judgment rather than based on pressure from the government (Peng, 2003). Thus, if formal institutions are well developed, political ties no longer positively influence the normative evaluation of a firm by beholders, and a firm does not obtain moral legitimacy due to its relationship with the government.

In contrast, if formal institutions are not well developed, beholders (including customers, investors, partners, and the public) value political ties and in turn endow firms that have political ties with more legitimacy. Thus, we offer the following hypothesis:

-

H4 The greater the degree of legal enforceability is, the weaker the positive effect of political ties on legitimacy.

Moderating effects of competitive intensity

Competitive intensity refers to the degree to which customers have alternative supply sources, which in turn influences whether they are less dependent on a particular supplier (Cannon & Perreault, 1999). Emerging markets usually experience an increase in private enterprises during an economic transition from a centrally planned economy to a market economy, which renders competitive intensity one of most fundamental variables reflecting the task environment. Consequently, we consider competitive intensity a moderator and argue that it can enhance the impact of market-focused innovation capability and firm legitimacy on firm performance.

As one of the most important dynamic capabilities, market-focused innovation capability represents the extent to which a firm introduces new products, new processes, and new systems required for adapting to changing markets, technologies and modes of competition (Dougherty & Hardy, 1996). Intense competition elevates consumers’ power in the market, which implies that customer satisfaction becomes imperative for improving performance (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993; Murray, Gao, & Kotabe, 2011). Market-focused innovation capability enables firms to better satisfy customers’ changing needs, so the importance of market-focused innovation capability is more salient in highly competitive markets than in minimally competitive markets. Intense competition erodes firm performance due to greater rivalry, which often leads to imitation (Chen, Lin, & Michel, 2010), price wars, promotion competition, and higher advertising costs (Auh & Menguc, 2005; Cui, Griffith, & Cavusgil, 2005). Market-focused innovation capability enables firms to build differentiation advantages through product and service innovation and reduce the cost of operations through process and management innovation, which in turn protects firm performance from aggressive competition.

In addition, competitive intensity accelerates market dynamism, which often results in market performance becoming nonlinear and less predictable (Eisenhardt, 1989). In such a market environment, firm performance relies much less on existing knowledge and much more on rapidly creating situation-specific new knowledge. Existing knowledge can even be a disadvantage if managers overgeneralize from past situations (Argote, 1999). A firm with greater market-focused innovation capability is likely to acquire and exploit new technology and knowledge to improve its performance in a dynamic market.

In sum, firms with high market-focused innovation capability can better translate competitive threats into beneficial opportunities; thus, intense competition in markets often results in firms placing a premium on innovation (Sirmon, Hitt, & Ireland, 2007). We therefore predict the following:

-

H5 The greater the level of competitive intensity is, the stronger the positive effect of market-focused innovation capability on performance.

As mentioned, legitimacy brings more revenue and lower costs to a firm through customer satisfaction, partner trust and cooperation, and public word-of-mouth. However, when competitive intensity is low in the industry, a firm that lacks sufficient legitimacy may perform well if its customers have no alternative options to satisfy their needs and wants, i.e., “customers are stuck with the organization’s products and services” (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993).

Competitive intensity not only reduces customer dependence on a particular supplier but also leads to perceived equalization regarding the quality of the products and services of different suppliers. This equalization then complicates differentiation based on aspects related to a firm’s core offering. In such cases, legitimacy, especially moral legitimacy, may be a useful tool to differentiate a firm from its rivals (Ven & Jeurissen, 2005), and a firm with more legitimacy has a competitive advantage. We therefore predict the following:

-

H6 The greater the level of competitive intensity is, the stronger the positive effect of legitimacy on performance.

Methods

Sample and data collection procedures

We obtained data for this study through a survey in central-western China and southeastern China. An English-language version of the questionnaire was prepared first and then translated into Chinese through a double back-translation process (Hoskisson et al., 2000; Li, Poppo, & Zhou, 2008). We controlled survey quality in the following ways. First, we promised each respondent about USD $1.5 for each valid questionnaire as an incentive. Second, to ensure that respondents were qualified, they were required to report their job position (e.g., general staff, junior manager, middle manager, and senior manager) in the firm. Since our questionnaire was related to the firm’s strategic activities, we excluded general staff from the sample. Furthermore, some respondents were excluded based on their answer to the question “Which business activities are you familiar with in the company?”

Since all questionnaire measures except the scales for legitimacy were drawn from previous studies, data were collected in two phases. The data from first phase was used to conduct exploratory factor analysis (EFA) for legitimacy and the data from second phase was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for all reflective scales and hypotheses testing. During the first phase, in-depth interviews were used to generate an initial item pool. With the help of the alumni association of a large university in China, we received 58 valid questionnaires from top managers. In the second phase, a formal questionnaire including legitimacy (13 items) and other constructs in our research were sent to the MBA Alumni Community of a university in China, and we asked alumni working in company managerial positions to provide information. Ultimately, 362 valid questionnaires were collected. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the samples.

Measures

Legitimacy

Following rigorous methods (Gerbing & Anderson, 1988), we developed a measurement for legitimacy. In the first stage, in-depth interviews with five experienced entrepreneurs and three professors in marketing were used to generate an initial pool of 22 items and an assessment of content validity. After that, we asked 80 top managers to evaluate their companies by completing the 22-item questionnaire. Based on 58 valid questionnaires, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .797, suggesting that factor analysis was appropriate. In the third step, an EFA was undertaken, and the analysis generated five factors with eigenvalues greater than one (together explaining 73.306% of the total variance; see Table 3). The items in the first four factors had a clear meaning, so according to the legitimacy definition of Dacin, Oliver, and Roy (2007), we could easily categorize them as relational legitimacy, social legitimacy, market legitimacy, and investment legitimacy. However, three items belonging to the last factor had different meanings, which meant that it was difficult to categorize the last factor. Given that this factor explained only 5.928% of the total variance, we deleted the unnamed factor from the formal scale. In addition, we removed six items from the measurement model due to weak loading or cross loading (Hogan et al., 2011). Table 3 shows the formal scale including the 13 items.

To further assess the factor structure of the legitimacy scale, a CFA was conducted. Specifically, the second-order construct operationalization with four first-order factors (relational legitimacy, investment legitimacy, social legitimacy and market legitimacy) was tested using 13 items of legitimacy. Table 4 shows that the measurement model fit the data satisfactorily.

Political ties and performance

The measures of political ties and performance are both four-item structures and adopted from Sheng, Zhou, and Li (2011). The measure of political ties captures the interpersonal relationship between managers and officials at various levels of government and regulatory organizations, such as tax bureaus, state banks, and commercial administration bureaus, and the scale also reflects substantial resources invested by firms in building relationships with government officials. The scales of performance consist of four items: sales growth rate, market share growth, profit growth rate, and return on investment compared to major firm competitors over the past year.

Legal enforceability and competitive intensity

Legal enforceability, reflecting the extent to which the legal system can protect firms’ business interests, was assessed based on a four-item scale from Zhou et al. (2010). Competitive intensity, as a traditional environmental factor, was captured by a mature five-item scale from Jaworski and Kohli (1993).

Market-focused innovation capability

Market-focused innovation capability refers to the ability to satisfy a market’s changing demand (Damanpour, Walker, & Avellaneda, 2009), which includes the ability to provide clients with new services and products (or the ability to solve clients’ problems in innovative ways) and the ability to implement innovative marketing programs. Drawing on Hogan et al., (2011), we used a nine-item scale to capture the extent of firms’ ability in client-based innovation activities and marketing-based innovation activities.

Control variables

To isolate potential confounding effects, we controlled for the following variables. 1) Firm age, which has an effect on the relationship between innovation and performance (Chen et al., 2014). We used the logarithm of the number of years the firm has been in operation to run a regression model. 2) Firm size, as measured by the natural logarithm of the number of firm employees (Sheng, Zhou, & Li, 2011). 3) Subsidiary, as defined by the answer to the question “Is the firm part of a larger firm?” because a subsidiary is likely to suffer interference from firm headquarters, which may affect firm performance (Birkinshaw, Hood, & Young, 2005). 4) The amount spent by the firm on research and development activities in the last three years, which affects future firm performance (Wu, 2011). 5) Export intensity (the percentage of export business to total sales) because firms with high levels of export intensity are more likely to attain legitimacy by adopting positive environmental strategies (Wu & Ma, 2016) and achieve better performance by improving their innovation capability (Smith, 2014).

Construct reliability and validity

We conducted a CFA to assess the reliability and validity of the reflective measure. Given the limited sample size, we divided the set of scales into two subgroups (Hewett & Bearden, 2001). The first measurement model included only legitimacy. The second measurement model included the remaining five factors: political ties, market-focused innovation capability, legal enforceability, competitive intensity, and firm performance. The first measurement models fit the data satisfactorily (χ2 (61) =182.966, p < .01; TLI = .964; CFI = .972; SRMR = .038; RMSEA = .074). The second measurement models also fit the data satisfactorily (χ2 (290) =564.221, p < .01; CFI = .969; TLI = .965; SRMR = .033; RMSEA = .051). All factor loadings for each construct were significant (p < .01). The composite reliability and AVE from all focal constructs (see Table 3 and Appendix) exceeded the .70 and .50 benchmarks, respectively. Thus, the measures demonstrated adequate reliability and convergent validity.

We assessed the discriminant validity of the measures in two ways. First, the AVE of each construct exceeded the squared correlation between construct pairs, demonstrating discriminant validity between the latent factors (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Second, according to chi-square difference tests for all paired constructs, the restricted model (correlation fixed at 1) was significantly worse than the freely estimated model (correlation estimated freely). Specifically, minimum Δχ2 (1) =8.30, p = .00, in support of discriminant validity.

Common method bias

In addition to implementing procedural controls for the survey, such as anonymous submission and minimization of the ambiguity of the measurement items, we conducted a test of common method variance by using the marker variable assessment technique approach recommended by Lindell and Whitney (2001). We added a variable regarding the geographical distance between the company and the province capital as the MV marker, which had no significant relation with the variables in our study (Lindell & Whitney, 2001). None of the significant correlations became insignificant after adjustment among the important constructs (see Table 5). Therefore, common method bias was unlikely to be a serious concern.

Results

We used bias-corrected bootstrapping (5000 samples taken from the data set) to test the mediating effects of innovation capability and legitimacy (Preacher & Hayes, 2008) (Table 6). We found that the indirect effect of political ties on performance via market-focused innovation capability was significant (supporting H1), with a point estimate of −.051 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of (−.096, −.015), which excludes zero. Likewise, the indirect effect of political ties on firm performance via legitimacy was significant (providing support for H2), with a point estimate of .030, 95% CI (.007 to .066).

In H3, we predicted that the direct effect of political ties on market-focused innovation capability would be moderated by legal enforceability. We found that the indirect effect of political ties on performance via market-focused innovation capability was significantly moderated by legal enforceability: the index of moderated mediation was .020, with a 95% CI (.001 to .043), which excluded zero (Table 7). Meanwhile, the results of Model 3 (Table 8) indicate that the coefficient of political ties × legal enforceability was significant and positive (β = .051, p < .05), and as indicated by the results of Model 2 (Table 8), the coefficient of political ties was significant and negative (β = −.320, p < .01). Figure 2 indicates that political ties were less negatively related to market-focused innovation capability with high legal enforceability (“high” defined as one standard deviation (s.d.) above the mean) than with low legal enforceability (defined as one s.d. below the mean). Thus, we found support for H3.

H4 predicted that the direct effect of political ties on legitimacy would be moderated by legal enforceability. As shown in Table 7, we found that the indirect effect of political ties on performance via firm legitimacy was significantly moderated by legal enforceability, with a moderated mediation index value of −.017 and a 95% CI (−.035 to −.005), which excluded zero. We also found (Model 6 in Table 8) that the coefficient of political ties × legal enforceability was significant and negative (β = −.039, p < .05) and that the coefficient of political ties was significant and positive (Model 5 in Table 8; β = .194, p < .01), thus supporting H4. This result is confirmed in Fig. 3: political ties were less positively related to legitimacy when legal enforceability was high (1 s.d. above the mean) than when legal enforceability was low (1 s.d. below the mean).

H5 predicted that the impact of market-focused innovation capability on firm performance would be moderated by competitive intensity. We found that the indirect effect of political ties on performance via market-focused innovation capability was significantly moderated by competitive intensity (Table 7), with a moderated mediation index value of −.007, 95% CI (−.018 to −.001), which excludes zero. As indicated by our results for Model 6 in Table 9, the coefficients of market-focused innovation capability × competitive intensity were significant and positive (β = .054, p < .01). Figure 4 shows the moderated effect of competitive intensity on the market-focused innovation capability-performance nexus; specifically, market-focused innovation capability was more positively related to performance when competitive intensity was high (1 s.d. above the mean) than when competitive intensity was low (1 s.d. below the mean). Hence, we found support for H5.

H6 predicted that the impact of legitimacy on firm performance would be moderated by competitive intensity. As shown in Table 7, we found that the indirect effect of political ties on performance via legitimacy was not significantly moderated by competitive intensity, with a moderated mediation index of .001 and a 95% CI (−.005 to .009), which included zero. We also found (Model 6 in Table 9) that the coefficient of legitimacy × competitive intensity was not significant (β = .008, p > .100); thus, we did not find support for H6. This may be because competitive intensity has opposite impacts on the implied performance of customer satisfaction and customer identification as induced by firm legitimacy. Specifically, intense competition exposes customers more frequently to more competitive offerings, which may result in customers revising their expectations (Mehta, Chen, & Narasimhan, 2008). Thus, satisfied customers in a more competitive market are less willing to pay than customers in a less competitive market. In contrast, competitive intensity may enhance the impact of customers’ identification on their willingness to pay. Previous research has offered support for this suggestion. For example, Haumann et al. (2014) found that customer identification reflects the extent to which a customer perceives overlap between his or her identity and that of an organization (Bhattacharya & Sen, 2003); thus, highly identified customers confronted with a high level of competitive advertising, to maintain self-consistency, are likely to accentuate the advantages of the offerings of the focal company with which they identify and devalue the competitive offerings.

Discussion and conclusion

Drawing on dynamic capability theory and institutional theory, we investigated how political ties play dual roles in an emerging market. Our results suggest that political ties have a metaphorical double-edged sword effect on firm performance in emerging economies; political ties can erode performance by inhibiting market-focused innovation capability, but they can also facilitate performance by enhancing firm legitimacy. In addition, we found that this dual effect is conditional on the institutional environment (legal enforceability buffers the negative impact of political ties on market-focused innovation capability but mitigates the positive impact of political ties on firm legitimacy), and the market environment, i.e., competitive intensity, is an important market factor that enhances the impact of market-focused innovation capability on firm performance.

Theoretical contributions

Our results contribute to the existing scholarly literature on political ties in the following ways. First, our study explored the political ties-performance nexus by examining the intermediate role of market-focused innovation capability and legitimacy. Unlike studies that shed light on only the positive underlying mechanism of the political ties-performance nexus (Guo, Xu, & Jacobs, 2014; Zhu, Su, & Shou, 2017), we provide insight into the bright side and the dark side of political ties simultaneously.

Second, we provide information on fundamental mediating mechanisms by testing the mediating effect of legitimacy in the relationship between political ties and performance. Extant research has provided insights into how political ties work to improve performance from the perspective of legitimacy (Peng & Luo, 2000; Sheng, Zhou, & Li, 2011). However, little if any research has examined the mediating effect of legitimacy on the political ties-performance nexus. We found that political ties can facilitate firm performance by sending beholders a signal that the firm has the ability and motivation to satisfy their pragmatic and moral expectations; consequently, our work constitutes a meaningful attempt to explain how political ties translate into firm performance from the perspective of institutional theory.

Third, our results suggest that the mediating effect of market-focused innovation capability and legitimacy depends on the institutional and market contexts. Thus, from a process-based perspective, our findings contribute to an enriched understanding of the relationship between political ties and performance. For example, we can explain why the impact of political ties on firm performance decreases with the improvement of legal enforceability; our results suggest that this occurs because legal enforceability buffers the erosion of political ties on innovation capability but mitigates the positive impact of political ties on legitimacy. In addition, we found that the impact of market-focused innovation capability on performance is positively associated with competitive intensity, which also explains why the positive impact of political ties on firm performance is not salient in a highly competitive market (Li, Poppo, & Zhou, 2008).

Furthermore, we developed a multi-dimensional measurement for legitimacy based on the insight of Dacin, Oliver, and Roy (2007). Specifically, we measured legitimacy from four dimensions: relational legitimacy, social legitimacy, market legitimacy and investment legitimacy. Compared with previous literature, the scale of legitimacy in our study provided a more detailed and insightful reconceptualization of the legitimacy construct.

Managerial implications

Our work has important implications for managers conducting business in emerging economies. First, we found that while political ties increase firm performance by fostering firm legitimacy, they erode firm performance by limiting market-focused innovation capability. This finding suggests that managers should be cautious in building political ties; specifically, seeking political ties would be an appropriate strategy for a firm without enough legitimacy (e.g., a foreign firm) but not a good choice for a firm that operates in an intensive competitive market because competitive intensity values market-focused innovation capability.

Second, we showed that legal enforceability decreases the negative influence of political ties on market-focused innovation capability but mitigates the positive impact of political ties on legitimacy. This result suggests that when formal institutions exist, a firm hoping to exploit political ties should keep an eye on its market-focused innovation capability in order to prevent those political ties from eroding its market-focused innovation capability.

Limitations and future research

Our results are subject to certain limitations that also suggest directions for further research. First, our results are context specific; thus, a natural extension would be to examine the roles of political ties in other transition economies. Second, we examined only legal enforceability and competitive intensity to determine the dominant mediator between political ties and performance. Additional studies should be conducted examining other factors, such as information verifiability, market uncertainty and organizational learning.

References

Argote, L. (1999). Organizational learning: Creating, retaining, and transferring knowledge: Kluwer academic publishers.

Auh, S., & Menguc, B. 2005. Top management team diversity and innovativeness: The moderating role of interfunctional coordination. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(3): 249–261.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. 2003. Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2): 76–88.

Birkinshaw, J., Hood, N., & Young, S. 2005. Subsidiary entrepreneurship, internal and external competitive forces, and subsidiary performance. International Business Review, 14(2): 227–248.

Boubakri, N., Cosset, J. C., & Saffar, W. 2008. Political connections of newly privatized firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(5): 654–673.

Cai, S., Jun, M., & Yang, Z. 2010. Implementing supply chain information integration in China: The role of institutional forces and trust. Journal of Operations Management, 28(3): 257–268.

Cannon, J. P., & Perreault, W. D. 1999. Buyer-seller relationships in business markets. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(4): 439–460.

Chen, M. J., Lin, H. C., & Michel, J. G. 2010. Navigating in a hypercompetitive environment: The roles of action aggressiveness and TMT integration. Strategic Management Journal, 31(13): 1410–1430.

Chen, V. Z., Li, J., Shapiro, D. M., & Zhang, X. 2014. Ownership structure and innovation: An emerging market perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(1): 1–24.

Chen, X., & Wu, J. 2011. Do different guanxi types affect capability building differently? A contingency view. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(4): 581–592.

Child, J., Chung, L., & Davies, H. 2003. The performance of cross-border units in China: A test of natural selection, strategic choice and contingency theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(3): 242–254.

Chung, H. F. L. 2011. Market orientation, guanxi, and business performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(4): 522–533.

Cui, A. S., Griffith, D. A., & Cavusgil, S. T. 2005. The influence of competitive intensity and market dynamism on knowledge management capabilities of multinational corporation subsidiaries. Journal of International Marketing, 13(3): 32–53.

Dacin, M. T., Oliver, C., & Roy, J. P. 2007. The legitimacy of strategic alliances: An institutional perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 28(2): 169–187.

Damanpour, F., Walker, R. M., & Avellaneda, C. N. 2009. Combinative effects of innovation types and organizational performance: A longitudinal study of service organizations. Journal of Management Studies, 46(4): 650–675.

Dougherty, D., & Hardy, C. 1996. Sustained product innovation in large, mature organizations: Overcoming innovation-to-organization problems. Academy of Management Journal, 39(5): 1120–1153.

Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal, 32(3): 543–576.

Fan, J. P. H., Wong, T. J., & Zhang, T. 2007. Politically connected ceos, corporate governance, and the post-ipo performance of china's partially privatized firms. Journal of Finance Economics, 84(2): 330–357.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. 1981. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1): 39–50.

Foroudi, P., Jin, Z., Gupta, S., Melewar, T. C., & Foroudi, M. M. 2016. Influence of innovation capability and customer experience on reputation and loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 69(11): 4882–4889.

Geletkanycz, M. A., & Black, S. S. 2001. Bound by the past? Experience-based effects on commitment to the strategic status quo. Journal of Management, 27(1): 3–21.

Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. 1988. An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating Unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research, 25(2): 186–192.

Greve, H. R., & Seidel, M. D. L. 2015. The thin red line between success and failure: Path dependence in the diffusion of innovative production technologies. Strategic Management Journal, 36(4): 475–496.

Gu, F. F., Hung, K., & Tse, D. K. 2008. When does Guanxi matter? Issues of capitalization and its dark sides. Journal of Marketing, 72(4): 12–28.

Guo, H., Xu, E., & Jacobs, M. 2014. Managerial political ties and firm performance during institutional transitions: An analysis of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Business Research, 67(2): 116–127.

Hadani, M., & Schuler, D. A. 2013. In search of El Dorado: The elusive financial returns on corporate political investments. Strategic Management Journal, 34(2): 165–181.

Handelman, J. M., & Arnold, S. J. 1999. The role of marketing actions with a social dimension: Appeals to the institutional environment. Journal of Marketing, 63(3): 33–48.

Haumann, T., Quaiser, B., Wieseke, J., & Rese, M. 2014. Footprints in the sands of time: A comparative analysis of the effectiveness of customer satisfaction and customer–company identification over time. Journal of Marketing, 78(6): 78–102.

Heirati, N., & O’Cass, A. 2016. Supporting new product commercialization through managerial social ties and market knowledge development in an emerging economy. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(2): 411–433.

Hewett, A. F., & Bearden, H. W. O. 2001. Dependence, trust, and relational behavior on the part of foreign subsidiary marketing operations: Implications for managing global marketing operations. Journal of Marketing, 65(4): 51–66.

Hillman, A. J., Zardkoohi, A., & Bierman, L. 1999. Corporate political strategies and firm performance: Indications of firm-specific benefits from personal service in the u.s. government. Strategic Management Journal, 20(1): 67–81.

Hogan, S. J., Soutar, G. N., Mccoll-Kennedy, J. R., & Sweeney, J. C. 2011. Reconceptualizing professional service firm innovation capability: Scale development. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(8): 1264–1273.

Hoskisson, R. E., Eden, L., Lau, C. M., & Wright, M. 2000. Strategy in emerging economies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3): 249–267.

Ismail Jr., K. M., Ford, D., Wu, Q., & Peng, M. W. 2013. Managerial ties, strategic initiatives, and firm performance in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30(2): 433–446.

Jansen, J. J. P., Bosch, F. A. J. V. D., & Volberda, H. W. 2006. Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science, 52(11): 1661–1674.

Jaworski, B. J., & Kohli, A. K. 1993. Market orientation: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Marketing, 57(3): 53–71.

Jiménez-Jiménez, D., & Sanz-Valle, R. 2011. Innovation, organizational learning, and performance. Journal of Business Research, 64(4): 408–417.

Laforet, S. 2008. Size, strategic, and market orientation affects on innovation. Journal of Business Research, 61(7): 753–764.

Li, J. J., Poppo, L., & Zhou, K. Z. 2008. Do managerial ties in China always produce value? Competition, uncertainty, and domestic vs. Foreign Firms. Strategic Management Journal, 29(4): 383–400.

Li, J. J., & Sheng, S. 2011. When does guanxi bolster or damage firm profitability? The contingent effects of firm- and market-level characteristics. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(4): 561–568.

Li, J. J., & Zhou, K. Z. 2010. How foreign firms achieve competitive advantage in the Chinese emerging economy: Managerial ties and market orientation. Journal of Business Research, 63(8): 856–862.

Li, J. J., Zhou, K. Z., & Shao, A. T. 2009. Competitive position, managerial ties, and profitability of foreign firms in China: An interactive perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(2): 339–352.

Li, W., He, A., Lan, H., & Yiu, D. 2012. Political connections and corporate diversification in emerging economies: Evidence from China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(3): 799–818.

Li, W., & Zhang, R. 2010. Corporate social responsibility, ownership structure, and political interference: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(4): 631–645.

Li, Y., Chen, H., Liu, Y., & Peng, M. W. 2014. Managerial ties, organizational learning, and opportunity capture: A social capital perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(1): 271–291.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. 2001. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1): 114–121.

Lu, Y., Zhou, L., Bruton, G., & Li, W. 2010. Capabilities as a mediator linking resources and the international performance of entrepreneurial firms in an emerging economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(3): 419–436.

Luo, Y. 2007. Are joint venture partners more opportunistic in a more volatile environment? Strategic Management Journal, 28(1): 39–60.

Mehta, N., Chen, X., & Narasimhan, O. 2008. Informing, transforming, and persuading: Disentangling the multiple effects of advertising on brand choice decisions. Marketing Science, 27(3): 334–355.

Murray, J. Y., Gao, G. Y., & Kotabe, M. 2011. Market orientation and performance of export ventures: The process through marketing capabilities and competitive advantages. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(2): 252–269.

Ngo, L. V., & O'Cass, A. 2013. Innovation and business success: The mediating role of customer participation. Journal of Business Research, 66(8): 1134–1142.

Peng, M. W. 2003. Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Academy of Management Review, 28(2): 275–296.

Peng, M. W., & Luo, Y. 2000. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3): 486–501.

Peng, M. W., & Zhou, J. Q. 2005. How network strategies and institutional transitions evolve in Asia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 22(4): 321–336.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3): 879–891.

Qian, C., Wang, H., Geng, X., & Yu, Y. 2017. Rent appropriation of knowledge-based assets and firm performance when institutions are weak: A study of Chinese publicly listed firms. Strategic Management Journal, 38(4): 892–911.

Sheng, S., Zhou, K. Z., & Li, J. J. 2011. The effects of business and political ties on firm performance: Evidence from China. Journal of Marketing, 75(1): 1–15.

Sirmon, D. G., Hitt, M. A., & Ireland, R. D. 2007. Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the Black box. Academy of Management Review, 32(1): 273–292.

Smith, S. W. 2014. Follow me to the innovation frontier? Leaders, laggards, and the differential effects of imports and exports on technological innovation. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(3): 248–274.

Sorensen, J. B., & Stuart, T. E. 2000. Aging, obsolescence, and organizational innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(1): 81–112.

Suchman, M. C. 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3): 571–610.

Ven, B. V. D., & Jeurissen, R. 2005. Competing responsibly. Business Ethics Quarterly, 15(2): 299–317.

Wang, G., Jiang, X., Yuan, C. H., & Yi, Y. Q. 2013. Managerial ties and firm performance in an emerging economy: Tests of the mediating and moderating effects. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30(2): 537–559.

Warren, D. E., Dunfee, T. W., & Li, N. 2004. Social exchange in China: The double-edged sword of Guanxi. Journal of Business Ethics, 55(4): 353–370.

Wu, J. 2011. Asymmetric roles of business ties and political ties in product innovation. Journal of Business Research, 64(11): 1151–1156.

Wu, J., & Chen, X. 2012. Leaders’ social ties, knowledge acquisition capability and firm competitive advantage. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(2): 331–350.

Wu, J., & Ma, Z. 2016. Export intensity and MNE customers’ environmental requirements: Effects on local Chinese suppliers’ environment strategies. Journal of Business Ethics, 135(2): 327–339.

Yan, J. Z., & Chang, S. J. 2018. The contingent effects of political strategies on firm performance: A political network perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 39(8): 2152–2177.

Yu, G., Shu, C., Xu, J., Gao, S., & Page, A. L. 2016. Managerial ties and product innovation: The moderating roles of macro- and micro-institutional environments. Long Range Planning, 50(2): 168–183.

Zhang, J., Tan, J., & Wong, P. K. 2015. When does investment in political ties improve firm performance? The contingent effect of innovation activities. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(2): 363–387.

Zheng, W., Singh, K., & Mitchell, W. 2015. Buffering and enabling: The impact of interlocking political ties on firm survival and sales growth. Strategic Management Journal, 36(11): 1615–1636.

Zhou, K. Z., Gao, G. Y., & Zhao, H. 2017. State ownership and firm innovation in China: An integrated view of institutional and efficiency logics. Administrative Science Quarterly, 62(2): 375–404.

Zhou, K. Z., & Li, C. B. 2007. How does strategic orientation matter in Chinese firms? Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(4): 447–466.

Zhou, K. Z., Li, J. J., Sheng, S., & Shao, A. T. 2014. The evolving role of managerial ties and firm capabilities in an emerging economy: Evidence from China. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(6): 581–595.

Zhou, K. Z., & Poppo, L. 2010. Exchange hazards, relational reliability, and contracts in China: The contingent role of legal enforceability. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(5): 861–881.

Zhou, K. Z., Yim, C. K., & Tse, D. K. 2005. The effects of strategic orientations on technology- and market-based breakthrough innovations. Journal of Marketing, 69(2): 42–60.

Zhu, W., Su, S., & Shou, Z. 2017. Social ties and firm performance. The mediating effect of adaptive capability and supplier opportunism. Journal of Business Research, 78(10): 226–232.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors and the reviewers for their insightful comments on the earlier versions of this manuscript. The authors also acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No.71532011 and 71872133) and the support from Philosophy and Social Sciences Research, Ministry of Education of P. R. China (Grants No. 14JZD017 and 18YJA630093).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Zhang, T. & Shou, Z. The double-edged sword effect of political ties on performance in emerging markets: The mediation of innovation capability and legitimacy. Asia Pac J Manag 38, 1003–1030 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-019-09686-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-019-09686-w