Abstract

Alcohol is a major contributor to the global burden of disease. In South Africa, alcohol abuse is hypothesized to correlate with women’s HIV status, mental health, and partner relationships over time. All pregnant women in 12 urban, low-income, Cape Town neighborhoods were interviewed at baseline, post-birth, and at 6, 12, 36, and 60 months following delivery with retention rates from 82.5 to 94%. Women were assessed for any alcohol use, problematic drinking, depression, intimate partner violence, and HIV status. Prior to pregnancy discovery and 5 years after giving birth, alcohol use was 25.8 and 24.7%, respectively. Most women decreased their alcohol use during pregnancy. Twenty-one percent reported alcohol use on two or more assessments, and only 15% of the mothers drinking alcohol at 5 years were also drinking at baseline. Mothers with depression had a higher likelihood of drinking alcohol compared to mothers who were not depressed only at baseline and 6 months post-birth. Mothers who experienced IPV had more than twice the likelihood of drinking alcohol compared to non-IPV mothers at all assessments. HIV positive mothers were more likely to drink alcohol compared to mothers without HIV prior to pregnancy discovery and at 5 years post-birth. These longitudinal trends in alcohol use among young women in South Africa represent a large economic, social, and health burden and must be addressed in a comprehensive manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Alcohol use has been recognized as a major contributor to the global burden of disease, with an even greater detrimental effect in low and middle income countries (LMICs) and people living in poverty [1, 2]. South Africa has one of the highest rates of alcohol consumption globally and alcohol consumption per capita has risen over the last 10 years [3, 4]. In South Africa, alcohol use plays a role in about half of all non-natural deaths [5]. It is involved in 75% of homicides; 60% of automobile accidents; and 24% of vehicular deaths and injuries [6, 7]. It is the third-largest contributor to death and disability after unsafe sex/sexually transmitted infections and interpersonal violence, both of which are themselves influenced by alcohol consumption as alcohol disinhibits sexual and violent behavior [2, 8]. In total, more than 13 million disability-adjusted life years, or 7% of the total disease burden in South Africa, is attributed to alcohol [9, 10].

Young people aged 15–29 years have the greatest burden of disease attributable to alcohol use [2]. Although, men generally use and abuse alcohol more frequently and experience a greater burden of disease than women [11], a significant proportion of young, black women in South Africa are also using alcohol [12, 13]. Women in disadvantaged communities with comparable alcohol use to men are significantly less likely to obtain treatment [14, 15]. Alcohol use in young women is associated with high rates of multiple comorbidities, including risky sexual practices, poor adherence to HIV medications, depression, and intimate partner violence (IPV) [16,17,18,19]. Alcohol use among mothers can have long-standing negative effects on their children and their ability to thrive given their homes are often less organized, routines are more chaotic and maternal adherence to health regimens suffer [20]. Furthermore, alcohol use in young women results in a large number of children in South Africa born with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). At first grade, some communities have a 9.5% rate of FASD [21].

HIV

In addition to alcohol consumption, HIV prevalence in South Africa are among the highest in the world [22]. With over 7 million people living with HIV and 270,000 new infections per year, the HIV epidemic in South Africa has led to the urgent development of HIV prevention programs. [23,24,25]. Alcohol use has continuously been shown to be associated with sexual risks for HIV and sexually transmitted infections [26,27,28]. As alcohol consumption increases, HIV prevalence also increases [29]. Furthermore, alcohol use has been shown to accelerate HIV disease progression [22].

Depression

Alcohol is a depressant. Alcohol use and major depressive disorders often co-occur, exacerbating the morbidity and mortality of each risk [30,31,32,33]. Individuals with depression and alcohol abuse have greater life dissatisfaction, functional impairment, and are at higher risk for suicide [34]. For women, the onset of new depression is highest during the perinatal period and women living in LMIC are at particularly high risk during this time [35, 36]. Rates of perinatal depression in South Africa have been found to be between 34 and 48% [37,38,39]. In addition to being correlated with alcohol use, depression in women during the perinatal period has been related to low income, poor partner support, and IPV [40,41,42,43,44,45].

Intimate Partner Violence

IPV against women is prevalent in South Africa, especially in low-income townships [46,47,48]. Approximately one in four South African women have been in an abusive relationship [48] and 30% of ever-partnered women have experienced IPV in their lifetime [49]. Being a victim of IPV is associated with physical trauma, including intimate partner femicide, higher risk of HIV, poor reproductive outcomes, challenges to mental health and suicide attempts [48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

Almost all research in LMIC on these risks is cross-sectional and typically research addresses risks individually (i.e. either alcohol or depression or IPV). This article examines alcohol use among South African mothers up to 5 years after giving birth and the relationships between alcohol use, HIV status, depression, and IPV. A population cohort of almost all pregnant women in 12 neighborhoods in Cape Town townships were recruited with a high percentage repeatedly reassessed over time.

Methods

The Institutional Review Boards of University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), and Stellenbosch University approved the study, whose methods have previously been published [55]. Three independent teams were involved: assessment (Stellenbosch University), intervention (Philani Programme [56]), and data analyses (UCLA). Participants completed all assessments between 2009 and 2016 and were included in the following analyses performed in 2017. This sample reflects the participants in the control condition of a randomized controlled trial.

Neighborhoods and Participants

Neighborhoods included in this evaluation (n = 12) were located in low-income, peri-urban areas outside Cape Town, South Africa. A total of 12 low-income, urban women were hired by Stellenbosch University for study recruitment. From May 2009 to September 2010. Each recruiter went house to house to identify all adult pregnant women who were aged ≥ 18 years to obtain consent to be contacted by the assessment team. Participation was refused by only 2% of pregnant women. Additional low-income, urban women were recruited, trained, and certified to serve as interviewers who entered participants’ responses to the assessment measures on mobile phones.

The sample size comprised 594 women who were randomized to the standard care or the neighborhood condition. Follow-up assessments were conducted and 94.1% of mothers were reassessed at two-weeks post-birth, 89.1% at 6 months, 91.3% at 18 months, 85.1% at 3 years, and 82.5% at 5 years post-birth. All assessments were completed by 58.1% of mothers; 8.9% (n = 53) completed no follow-up re-assessments. A total of six participants died over the 5 year course of the study. The flow of participants over time is available from the authors upon request.

Maternal Measures

Alcohol Use

At each assessment, the frequency and the quantity of alcohol use was reported. There were varying time frames for women’s alcohol use reports at each assessment. At recruitment, alcohol use prior to pregnancy discovery was reported; at the post-birth assessment, alcohol use in the month prior to birth was reported. At 6 months, mothers reported on alcohol use since the baby was born. Finally, at the 18 month, 3, and 5 year assessments, mothers reported alcohol use in the month prior to the assessment. Alcohol dependence was assessed using the Derived Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Consumption (Derived AUDIT-C) [57], a three-item scale, each rated 0–4 on intensity; in women, a score greater than two represents problematic drinking [58].

HIV Status

Women self-reported their HIV status at each assessment time point. Further, all children received at birth a government-issued Road-to-Health Card on which mothers’ HIV status could be confirmed.

Depression

Maternal depressed mood was reported at each assessment using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [59], which has 10 items on a 0-3 likert scale. A cut-off of > 13 indicates depressed mood [39].

Intimate Partner Violence

Women reported at each assessment time point (except 2 weeks post-birth) whether they had been slapped, pushed or shoved, and/or threated with a weapon by a current partner in the past 12 months. On three items, any positive response indicated IPV.

Data Analysis

Our analyses examined mothers’ reported alcohol use by depression, IPV, and maternal HIV status over time. Comparisons were performed separately for the any alcohol use and problematic drinking measures. Differences in alcohol use measures were assessed using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests for discrete variables at each time point. We used SAS 9.4 and Stata® SE software version 14.2 [60].

Results

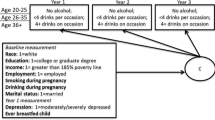

At the baseline assessment conducted during pregnancy, the average age of women in the study sample was 26.3 (standard deviation = 5.6) years. The average education level was slightly higher than 10th grade. There were 18% who were currently employed, 55% were married or lived with a partner, and 48% had a monthly household income greater than 2000 rand (151.44 USD). About 32% lived in formal housing with 55% having water on site, and 58 and 91% had a flush toilet and electricity on site, respectively. Fifty-one percent of women at baseline experienced food insecurity (i.e., hungry on more than 2 days in the past week) and 31% of previous children of the pregnant women experienced food insecurity.

The percentage of any alcohol use and problematic drinking over time is shown in Fig. 1. Prior to pregnancy discovery, there were very high rates of any alcohol use and problematic drinking. After discovery, there was a substantial drop in problematic drinking, documented by reports of alcohol use in the month prior to birth. Beginning at six-months post-birth, the rate of drinking began to rise and continued to increase to the rate reported prior to recognizing that they were pregnant. The rates of problematic drinking at 5 years post-birth exceeded the rates of problematic drinking prior to discovery of pregnancy. Over the 5 year study period, 63.3% of mothers did not report any alcohol use, 15.8% reported at on assessment point, and 20.9% reported two or more of the assessment periods. Similarly, 67.3% reported no problematic drinking, 17.0% reported at one assessment, and 15.7% reported problematic drinking at two or more assessments. Among the mothers reporting any alcohol use at 5 years, 15% had also reported drinking at baseline. Also, 11% of mothers who had problematic drinking at 5 years also reported problematic drinking at baseline.

Alcohol Use by Depression

Over the 5 year study period 56% of mothers reported experiencing depression for at least one time point. Depressed mothers had a significantly higher percentage of drinking any alcohol compared to non-depressed mothers when assessed prior to pregnancy discovery [χ2 (1, n = 500) = 6.85, p = 0.01; Odds Ratio (OR) 1.72]. There was a very large drop in any alcohol use during pregnancy reflected in reports in the month prior to birth, with rates similar across depressed and not depressed mothers. At six-months post-birth, depressed mothers were more than twice as likely to drink any alcohol compared to non-depressed mothers [χ2 (1, n = 487) = 9.67, p < 0.001; OR 2.63]. While rates of drinking any alcohol continued to rise through 5 years post-birth, there were no significant differences comparing depressed and non-depressed mothers. The pattern of the relationship between alcohol use and depression is very similar to that of problematic drinking. Therefore, the percentage of problematic drinking over time by depression status is shown in Fig. 2. Mothers’ problematic drinking followed a similar trend over time as those drinking any alcohol. Prior to knowledge of pregnancy, depressed mothers were more likely to have problematic drinking compared to non-depressed mothers [χ2 (1, n = 500) = 4.79, p = 0.03; OR 1.64]. Depressed mothers were also more than twice as likely to have problematic drinking compared to non-depressed mothers at six-months post-birth [χ2 (1, n = 487) = 7.13, p = 0.01; OR 2.51]. However, there were no significant differences at later time points.

Alcohol Use by IPV

Over the 5 year study period, 48% of mothers reported experiencing IPV during at least one time point. Any alcohol use was significantly associated with IPV at each time point: prior to pregnancy discovery [χ2 (1, n = 499) = 30.39, p < 0.001; OR 3.12], at 6 months post-birth [χ2 (1, n = 487) = 16.95, p < 0.001; OR 3.32], 18 months [χ2 (1, n = 483) = 43.29, p < 0.001; OR 6.06], 3 years [χ2 (1, n = 454) = 36.62, p < 0.001; OR 5.26], 5 years [χ2 (1, n = 442) = 28.85, p < 0.001; OR = 4.48]. Mothers who experienced IPV consistently had higher percentages of any alcohol use over time compared to those who did not experience violence. Similarly, there were significant differences in problematic drinking by IPV when assessed prior to pregnancy discovery [χ2 (1, n = 499) = 28.33, p < 0.001; OR 3.30], at 6 months [χ2 (1, n = 487) = 16.46, p < 0.001; OR 3.66], 18 months [χ2 (1, n = 483) = 33.59, p < 0.001; OR 5.63], 3 years [χ2 (1, n = 454) = 44.18, p < 0.001; OR 6.08], and 5 years [χ2 (1, n = 442) = 36.64, p < 0.001; OR 5.40] post-birth. The percentage of problematic drinking over time by IPV is shown in Fig. 3. Mothers who experienced IPV had greater than twice the likelihood of having problematic drinking (similar to any alcohol use) over time compared to non-IPV mothers.

Alcohol Use by HIV Status

HIV positive mothers had a significantly higher percentage of drinking any alcohol compared to HIV negative mothers when assessed prior to pregnancy discovery [χ2 (1, n = 460) = 4.12, p = 0.04; OR 1.56]. There was a very large drop in any alcohol use during pregnancy reflected in reports in the month prior to birth, with rates similar across mothers regardless of HIV status. Drinking rates began to rise from 6 months post-birth to 3 years post-birth and were similar between mothers. However, at 5 years post-birth, HIV positive mothers were significantly more likely to drink any alcohol compared to HIV negative mothers [χ2 (1, n = 439) = 10.23, p < 0.001; OR 2.05]. The pattern of the relationship between alcohol use and maternal HIV status is very similar to the pattern of problematic drinking and, therefore, the percentage of problematic drinking over time by maternal HIV status is shown in Fig. 4. Prior to knowledge of pregnancy, HIV positive mothers were more likely to have problematic drinking compared to HIV negative mothers [χ2 (1, n = 460) = 6.29, p = 0.01; OR 1.80]. A significant drop in problematic drinking in the month prior to birth occurred followed by an increase from 6 months post-birth to 3 years post-birth with rates similar between mothers regardless of HIV status. Similar to any alcohol use, HIV positive mothers were significantly more likely to have problematic drinking compared to HIV negative mothers at 5 years post-birth [χ2 (1, n = 439) = 7.82, p = 0.01; OR 1.92].

Discussion

This paper shows the longitudinal patterns of alcohol use and problematic drinking among poor women in peri-urban South African townships before pregnancy discovery through the first 5 years after giving birth. Our sample population has similar rates of alcohol use among women to those reported by other researchers, which have ranged from 17 to 42% [5, 12, 13, 61, 62]. Many women in our sample continued to drink during pregnancy, but there was an encouraging drop once women were aware of their pregnancy. We found this effect to be relatively stable when asked at the time of recruitment (9.2%) and when asked postpartum about the month before giving birth (7.2%). However, this may be in part due to false self-reporting, as previous studies of pregnant women have indicated that up to 20.2% continued to use alcohol while pregnant [13]. The utility of biomarkers in future studies may reduce the effect of self-report bias or social desirability bias. In the five-year post-partum period in our study, drinking behavior gradually returned to the high levels seen at baseline, prior to pregnancy discovery.

It is important to note, however, that of the study participants who were reporting any alcohol use and problematic drinking 5 years after giving birth were not the same study participants that reported these behaviors at baseline. The relatively small percentages of mothers using any alcohol or reporting problematic drinking at both baseline and five-years post-birth (15 and 11%, respectively) indicate that there is more going on than a simple return to drinking behavior. We have previously reported on the stability in drinking behavior seen over time in this study [63], but further research is needed to determine why some mothers return to drinking and some do not, and why some mothers begin drinking several years post-birth who were not drinking before. A more thorough understanding of what contributes to alcohol use among South African mothers is needed.

Parallel to previous research, HIV positive mothers in the current study had higher rates of drinking any alcohol compared to HIV negative mothers when assessed prior to pregnancy discovery and 5 years post birth [26, 27, 64]. Similarly, mothers with HIV were also more likely to engage in problematic drinking compared to HIV negative mothers at those time points. Alcohol use was similar among HIV positive and negative mothers during pregnancy, 6 months post birth, and 3 years post birth. The drop in alcohol consumption seen among all mothers upon pregnancy discovery and throughout pregnancy has been demonstrated in other studies [12, 65].

Depression was found to be extremely common among South African mothers. Our findings support previous research studies that have found high rates of depression in South African women ranging from 30 to 50%, with our rates even exceeding those reports [37, 38, 62]. Several other studies have demonstrated a correlation between alcohol use and depression [31, 66, 67]; however, our longitudinal study has shown that this may only be true during the more stressful and vulnerable antenatal and postnatal time periods [68].

In our sample, almost half of mothers reported having experienced IPV at some point during the study. This is similar to previously reported rates of IPV in other South African studies [69, 70]. Additionally, this five-year follow-up continues to report the strong correlation between IPV, alcohol use and problematic drinking in mothers. The negative impact associated with IPV which has been previously reported [63], persists to 60 months. It remains unclear whether this represents continued relationships with one violent partner or new partners engaging in IPV. In either scenario, the increased risk for alcohol use and problematic drinking appears to become more significant over time. The reported two-fold increase in risk for alcohol use among victims of IPV is consistent with previous studies [71].

Alcohol abuse in South Africa is an urgent public health priority, and the country has set a goal to reduce its per capita consumption 20% by 2020 [72]. With a shortage of medical professionals to address this problem and other chronic diseases, LMIC are increasingly using community health workers (CHWs) to implement interventions and improve quality of care [73, 74]. However, despite the multiple health challenges associated with poverty in LMIC, CHWs typically address only a single health challenge—for example, to reduce perinatal HIV transmission, low birth weight infants, or malnutrition [75,76,77,78,79,80]. Yet, a single modal approach to reducing alcohol use may not be effective in the context of multiple serious comorbidities that we demonstrated in this article: alcohol, HIV, depression, and IPV.

Conclusions

This study supports previous cross-sectional work showing the high rates of alcohol use and problematic drinking in women in of reproductive age in South Africa of reproductive age. However, cross sectional studies, which are common in LMIC, limit the ability to demonstrate the effect of an intervention and trends over time [81]. Following this cohort of mothers over 5 years after an initial pregnancy allows us to see both how persistent alcohol use is and the considerable discontinuity in use and abuse over time. Women who receive a preventative intervention during the prenatal period do reduce their alcohol use [82], but continued support, and recognition of other psychosocial factors, may be required to make a more lasting impact. These women re-initiated alcohol use post-pregnancy.

Previous studies focusing on single outcomes do not adequately reveal how alcohol contributes to women’s health and may not sufficiently characterize the influence of alcohol consumption on IPV, depression, and sexually transmitted infections [83,84,85]. Our study strongly supports the correlation between IPV and alcohol use overtime and contributes to the understanding of these two variables. However, depression, alcohol use and problematic drinking only appear linked in the peri-natal period. It is possible that other factors associated with depression, such as a lack of financial resources, no partner, and food insecurity [86], cause more stress and lead to more drinking, for mothers during these time periods and not in the years after birth. Conversely, the correlation between HIV and alcohol use is not seen during the peri-natal period. HIV+ mothers may receive greater counseling at clinics during this time period, or may be more careful about alcohol use when they are concerned about HIV transmission. Finding ways to extend this healthy choice beyond the peri-natal period is important.

An important consideration for future researchers is the impact that alcohol use, depression, and the maternal experience of IPV have on children [87]. These factors have been associated with children experiencing physical and emotional abuse by caregivers [38, 88, 89], and lead to increased alcohol use, mental health problems, and future IPV (both perpetration and victimization) as children become young adults [75, 90, 91]. Long term follow-up of the children of alcohol using, HIV+ or depressed mothers, and mothers who have experienced IPV could help identify additional harmful or protective factors.

References

World Health Organization. Alcohol in developing societies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–33.

World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2015. Geneva: Switzerland; 2015.

Parry CD. South Africa: alcohol today. Addiction. 2005;100(4):426–9.

Frontline Felowship. Alcohol Abuse in South Africa. 2007. http://www.frontline.org.za/index.php?option=com_content&id=466:alcohol-abuse-in-south-africa.

Peer N, Matzopoulos R, Myers JE. The number of motor vehicle crash deaths attributable to alcohol-impaired driving and its cost to the economy between 2002 and 2006 in South Africa. Cape Town: University of Cape Town; 2009.

Parry CD, Rehm J, Poznyak V, Room R. Alcohol and infectious diseases: an overlooked causal linkage? Addiction. 2009;104(3):331–42.

Bradshaw D, Groenewald P, Laubscher R, Nannan N, Nojilana B, Norman R, et al. Initial burden of disease estimates for South Africa, 2000. S Afr Med J. 2003;93(9):682–8.

Matzopoulos RG, Truen S, Bowman B, Corrigall J. The cost of harmful alcohol use in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2014;104(2):127–32.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA]. National HouseholdSurvey on Drug Abuse. 2005.

Desmond K, Milburn N, Richter L, Tomlinson M, Greco E, van Heerden A, et al. Alcohol consumption among HIV-positive pregnant women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: prevalence and correlates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1):113–8.

Vythilingum B, Roos A, Faure SC, Geerts L, Stein DJ. Risk factors for substance use in pregnant women in South Africa. Samj S Afr Med J. 2012;102(11):851–4.

Burnhams NH, Dada S, Myers B. Social service offices as a point of entry into substance abuse treatment for poor South Africans. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2012;7:22.

Myers B, Vythylingum B. Women and alcohol. Substance Use and Abuse in South Africa: Brain, Behavioural and Other Perspectives. Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press; 2012.

Morojele NK, Brook JS. Sociodemographic, sociocultural, and individual predictors of reported feelings of meaninglessness among South African adolescents. Psychol Rep. 2004;95(3 Pt 2):1271–8.

Naimi TS, Lipscomb LE, Brewer RD, Gilbert BC. Binge drinking in the preconception period and the risk of unintended pregnancy: implications for women and their children. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 2):1136–41.

Tomlinson M, Grimsrud AT, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Myer L. The epidemiology of major depression in South Africa: results from the South African stress and health study. S Afr Med J. 2009;99(5 Pt 2):367–73.

Rico E, Fenn B, Abramsky T, Watts C. Associations between maternal experiences of intimate partner violence and child nutrition and mortality: findings from Demographic and Health Surveys in Egypt, Honduras, Kenya, Malawi and Rwanda. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2011;65(4):360–7.

Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(2):180–202.

Li Q, Fisher WW, Peng CZ, Williams AD, Burd L. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a population based study of premature mortality rates in the mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(6):1332–7.

UNAIDS. UNAIDS DATA 2017. Switzerland; 2017.

Bhardwaj S, Barron P, Pillay Y, Treger-Slavin L, Robinson P, Goga A, et al. Elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in South Africa: rapid scale-up using quality improvement. S Afr Med J. 2014;104(3 Suppl 1):239–43.

Sherman GG, Lilian RR, Bhardwaj S, Candy S, Barron P. Laboratory information system data demonstrate successful implementation of the prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2014;104(3 Suppl 1):235–8.

UNAIDS. AIDS by the numbers Geneva, Switzerland UNAIDS; 2015. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/AIDS_by_the_numbers_2015_en.pdf.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8(2):141–51.

Russell BS, Eaton LA, Petersen-Williams P. Intersecting epidemics among pregnant women: alcohol use, interpersonal violence, and HIV infection in South Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(1):103–10.

Probst C, Simbayi LC, Parry CDH, Shuper PA, Rehm J. Alcohol use, socioeconomic status and risk of HIV infections. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1926–37.

NIAAA. Alcohol Alert. Rockville: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2002.

Schuckit MA. Comorbidity between substance use disorders and psychiatric conditions. Addiction. 2006;101(Suppl 1):76–88.

Boschloo L, Vogelzangs N, Smit JH, van den Brink W, Veltman DJ, Beekman AT, et al. Comorbidity and risk indicators for alcohol use disorders among persons with anxiety and/or depressive disorders: findings from the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Affect Disord. 2011;131(1–3):233–42.

Gadermann AM, Alonso J, Vilagut G, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Comorbidity and disease burden in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(9):797–806.

Blanco C, Alegria AA, Liu SM, Secades-Villa R, Sugaya L, Davies C, et al. Differences among major depressive disorder with and without co-occurring substance use disorders and substance-induced depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatr. 2012;73(6):865–73.

Briere FN, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Klein D, Lewinsohn PM. Comorbidity between major depression and alcohol use disorder from adolescence to adulthood. Compr Psychiatr. 2014;55(3):526–33.

Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2008;65(7):805–15.

Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, Einarson TR. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(4):698–709.

Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Landman M, Molteno C, Stein A, et al. Improving quality of mother-infant relationship and infant attachment in socioeconomically deprived community in South Africa: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b974.

Madu SN, Idemudia SE, Jegede AS. Perceived parental disorders as risk factors for child sexual, physical and emotional abuse among high school students in the Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. J Soc Sci. 2002;2:103–12.

Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Newell ML, Stein A. Detection of antenatal depression in rural HIV-affected populations with short and ultrashort versions of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(5):401–10.

Pajuloa M, Savonlahtia E, Sourandera A, Heleniusb H, Pihaa J. Antenatal depression, substance dependency and social support. J Affect Disord. 2001;65:9–17.

Tomlinson M, Swartz L, Cooper PJ, Molteno C. Social factors and postpartum depression in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. S Afr J Psychol. 2004;34(3):409–20.

Lovisi GM, Lopez JR, Coutinho ES, Patel V. Poverty, violence and depression during pregnancy: a survey of mothers attending a public hospital in Brazil. Psychol Med. 2005;35(10):1485–92.

Horrigan TJ, Schroeder AV, Schaffer RM. The triad of substance abuse, violence, and depression are interrelated in pregnancy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;18(1):55–8.

Patel V, Rodrigues M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: a study of mothers in Goa, India. Am J Psychiatr. 2002;159(1):43–7.

Ramchandani PG, Richter LM, Stein A, Norris SA. Predictors of postnatal depression in an urban South African cohort. J Affect Disord. 2009;113(3):279–84.

Devries KM, Child JC, Bacchus LJ, Mak J, Falder G, Graham K, et al. Intimate partner violence victimization and alcohol consumption in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2014;109(3):379–91.

Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):41–8.

Jewkes R, Levin J, Penn-Kekana L. Risk factors for domestic violence: findings from a South African cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(9):1603–17.

Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, Child JC, Falder G, Petzold M, et al. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10(5):e1001439.

Coker AL. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trauma Viol Abus. 2007;8(2):149–77.

Campbell C, Williams B, Gilgen D. Is social capital a useful conceptual tool for exploring community level influences on HIV infection? An exploratory case study from South Africa. Aids Care. 2002;14(1):41–54.

Bonomi AE, Thompson RS, Anderson M, Reid RJ, Carrell D, Dimer JA, et al. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical, mental, and social functioning. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(6):458–66.

Seedat S, Stein MB, Forde DR. Association between physical partner violence, posttraumatic stress, childhood trauma, and suicide attempts in a community sample of women. Viol Vict. 2005;20(1):87–98.

Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363(9419):1415–21.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Mbewu N, Comulada WS, le Roux K, et al. Philani Plus (+): a Mentor Mother community health worker home visiting program to improve maternal and infants’ outcomes. Prev Sci. 2011;12(4):372.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tomlinson M, le Roux IM, Harwood JM, Comulada S, O’Connor MJ, et al. A cluster randomised controlled effectiveness trial evaluating perinatal home visiting among South African Mothers/Infants. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e105934.

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791.

Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS. The AUDIT-C: screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the presence of other psychiatric disorders. Compr Psychiatr. 2005;46(6):405–16.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression—Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatr. 1987;150:782–6.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station: StataCorp LP.; 2015.

Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Jooste S, Mathiti V, Cain D, Cherry C. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV infection among men and women receiving sexually transmitted infection clinic services in Cape Town, South Africa. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(4):434–42.

Wong FY, Huang ZJ, DiGangi JA, Thompson EE, Smith BD. Gender differences in intimate partner violence on substance abuse, sexual risks, and depression among a sample of South Africans in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20(1):56–64.

Rotheram-Borus MD, Tomlinson M, Le Roux I, Stein JA. Alcohol use, partner violence, and depression a cluster randomized controlled trial among urban South African mothers over 3 years. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(5):715–25.

Choi KW, Abler LA, Watt MH, Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Skinner D, et al. Drinking before and after pregnancy recognition among South African women: the moderating role of traumatic experiences. BMC Preg Childbirth. 2014;14:97.

Urban MF, Olivier L, Louw JG, Lombard C, Viljoen DL, Scorgie F, et al. Changes in drinking patterns during and after pregnancy among mothers of children with fetal alcohol syndrome: a study in three districts of South Africa. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;168:13–21.

Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Alcohol and depression. Addiction. 2011;106(5):906–14.

Rubio DM, Kraemer KL, Farrell MH, Day NL. Factors associated with alcohol use, depression, and their co-occurrence during pregnancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(9):1543–51.

Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Barnighausen T, Newell ML, Stein A. The prevalence and clinical presentation of antenatal depression in rural South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2011;135(1–3):362–73.

World Health Organization. Understanding and addressing violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

Townsend L, Jewkes R, Mathews C, Johnston LG, Flisher AJ, Zembe Y, et al. HIV risk behaviours and their relationship to intimate partner violence (IPV) among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):132–41.

Gass JD, Stein DJ, Williams DR, Seedat S. Gender differences in risk for intimate partner violence among South African adults. J Interpers Viol. 2011;26(14):2764–89.

Mayosi BM, Lawn JE, van Niekerk A, Bradshaw D, Abdool Karim SS, Coovadia HM. Health in South Africa: changes and challenges since 2009. Lancet. 2012;380(9858):2029–43.

Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, Daniels K, Bosch-Capblanch X, van Wyk BE, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD004015.

Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370(9591):991–1005.

Alderman H. Improving nutrition through community growth promotion: longitudinal study of the nutrition and early child development program in Uganda. World Dev. 2007;35(8):1376–89.

Alderman H, Hoogeveen H, Rossi M. Preschool nutrition and subsequent schooling attainment: longitudinal evidence from Tanzania. Econ Dev Cult Change. 2009;57(2):239–60.

Alderman H, Ndiaye B, Linnemayr S, Ka A, Rokx C, Dieng K, et al. Effectiveness of a community-based intervention to improve nutrition in young children in Senegal: a difference in difference analysis. Public Health Nutrition. 2009;12(5):667–73.

le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, Harwood JM, O’Connor M, Worthman CM, Mbewu N, et al. Outcomes of home visits for pregnant mothers and their infants: a cluster randomised controlled trial. AIDS. 2013;27(9):1461.

Richter L, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Van Heerden A, Stein A, Tomlinson M, Harwood JM, et al. Pregnant women living with HIV (WLH) supported at clinics by peer WLH: a cluster randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):706–15.

Tyllekar T, Jackson D, Meda N, Engebretsen IM, Chopra M, Diallo AH, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding promotion by peer counsellors in sub-Saharan Africa (PROMISE-EBF): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):420–7.

Sedgwick P. Cross sectional studies: advantages and disadvantages. BMJ. 2014. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2276.

le Roux IM, le Roux K, Mbeutu K, Comulada WS, Desmond KA, Rotheram-Borus MJ. A randomized controlled trial of home visits by neighborhood mentor mothers to improve children’s nutrition in South Africa. Vulnerab Child Youth Stud. 2011;6(2):91–102.

Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC, Eaton LA, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, Skinner D. Gender-based violence and HIV sexual risk behavior: alcohol use and mental health problems as mediators among women in drinking venues, Cape Town. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(8):1417–25.

Shamu S, Abrahams N, Temmerman M, Musekiwa A, Zarowsky C. A systematic review of African studies on intimate partner violence against pregnant women: prevalence and risk factors. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(3):e17591.

Jina R, Jewkes R, Hoffman S, Dunkle KL, Nduna M, Shai NJ. Adverse mental health outcomes associated with emotional abuse in young rural South African women: a cross-sectional study. J Interpers Viol. 2012;27(5):862–80.

Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, Comulada S, Stewart J, Le Roux I, et al. Depressed mood in pregnancy: Prevalence and correlates in two Cape Town per-urban settlements. BMC Reproductive Health. 2011;8(1):9.

World Health Organization. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

Makoae M, Dawes A, Loffell J, Ward CL. Children’s court inquiries in the Western Cape. Western Cape: Human Sciences Research Council; 2008.

Meinck F, Cluver LD, Boyes ME, Ndhlovu LD. Risk and protective factors for physical and emotional abuse victimisation amongst vulnerable children in South Africa. Child Abuse Rev. 2015;24(3):182–97.

Widom CS, Hiller-Sturmhofel S. Alcohol abuse as a risk factor for and consequence of child abuse. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25(1):52–7.

Hoque M, Ghuman S. Do parents still matter regarding adolescents’ alcohol drinking? Experience from South Africa. Int J Env Res Pub He. 2012;9(1):110–22.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1R01AA017104), the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH109205), the UCLA Center for HIV Identification, Prevention and Treatment Services (P30MH58107), the UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (UL1TR000124), the UCLA Center for AIDS Research (P30AI028697), Ilifa Labantwana, the ELMA Foundation, the DG Murray Trust, and National Research Foundation (South Africa) and the Department for International Development (DfID-UK). ClinicalTrials.gov registration #NCT00972699.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, E.C., Rotheram-Borus, M.J., Weichle, T.W. et al. Patterns of Alcohol Abuse, Depression, and Intimate Partner Violence Among Township Mothers in South Africa Over 5 Years. AIDS Behav 21 (Suppl 2), 174–182 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1927-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1927-y