Abstract

The purpose of this study is to investigate a) longitudinal patterns of maternal postpartum alcohol use as well as its variation by maternal age at child birth and b) within maternal age groups, the association between other maternal characteristics and alcohol use patterns for the purposes of informed prevention design. Study sample consists of 3397 mothers from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study representing medium and large US urban areas. Maternal drinking and binge drinking were measured at child age 1, 3, and 5 years. We conducted separate longitudinal latent class analysis within each of the three pre-determined maternal age groups (ages 20–25, n = 1717; ages 26–35, n = 1367; ages 36+, n = 313). Results revealed different class structures for maternal age groups. While two classes (NB [non-binge]-drinkers and LL [low-level]-drinkers) were identified for mothers in each age group, a third class (binge drinkers) was separately distinguished for the two older age groups. Whereas binge drinking rates appear to remain stable over the 5 years postdelivery for mothers who gave birth in their early twenties, mothers ages 26 and older increasingly engaged in binge drinking over time, surpassing the binge drinking behavior of younger mothers. Depression significantly increases the odds of being a NB-drinker for the 20–25 age group and that of being a binge drinker for the 36+ age group, whereas smoking during pregnancy is associated with subsequent binge drinking only for mothers ages 20–25. Findings highlight the importance of distinguishing risk factors by maternal age groups for drinking while parenting a young child, to inform the design of intervention strategies tailored to mothers of particular ages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Alcohol use during pregnancy has been consistently found to be a leading cause of still birth, spontaneous abortion, and preterm delivery, as well as various child neurobehavioral problems, such as fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) and deficits in attention, memory, and IQ (Meyer-Leu et al. 2011). The fact that substance use during pregnancy increases the risks of adverse birth outcomes has inspired a growing body of research examining the patterns and risk factors of maternal perinatal alcohol consumption (Ethen et al. 2009). Ample epidemiological evidence about individual and environmental risk factors for substance use during pregnancy has led to the development of effective prevention programs, such as the Family-Nurse Partnership (Olds et al. 2002), as well as the implementation of state and federal legislations, such as the Title V of the Social Security Block Grants.

Following these prevention efforts during pregnancy and temporary declines in drinking (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2011), however, a significant proportion of new mothers resume alcohol consumption and even engage in binge drinking within a year postdelivery. Prevalence estimates of “any alcohol use” postpartum range from 30 % to nearly 50 %, and binge drinking range from 6 % to nearly 20 % (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007b; Laborde and Mair 2012; Muhuri and Gfroerer 2009). In addition to the well-established harmful effects of risky drinking (defined by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as consuming more than three drinks per occasion or more than seven per week for women) on mothers’ own health (Fan et al. 2008), two pathways have been suggested hypothesizing how mother’s alcohol use can pose a significant risk to the child’s well-being. Mothers may expose their child to alcohol through their breast milk. Such exposure has been shown to disrupt the infants’ sleep-wake patterns as well as motor development (Little et al. 1990). Postnatal excessive alcohol consumption, often accompanied by maternal distraction, neglect, unpredictable behavior, and other mental health issues, contributes to a deficient child rearing environment and poses risks to children during the first few years of life as they spend most of time with their mothers (Jester et al. 2000).

While it has been recognized that risky maternal drinking can be identified during pediatric visits (Jonas et al. 2012), prevention effort focusing on the period immediately after delivery (usually within a few months) has been found to be of limited effectivenss (Turnbull and Osborn 2012) or to have only short-term benefits (Fleming et al. 2008). Importantly, compared to mother’s drinking during pregnancy, only limited epidemiological data on alcohol use during the postpartem and early parenting periods is available to guide intervention efforts.

Pregnancy and child birth mark an important transition in a woman’s life characterized by psychosocial, economic, and logistical changes (Rutter 1996), and thus may facilitate a reduction in alcohol consumption through changing norms, expectations, and added responsibilities associated with being a parent (Fergusson et al. 2012; Staff et al. 2014). On the other hand, increased responsibilities and expectations associated with caring for a young child may also lead to stressful challenges in a woman’s life, which may reverse the initial protective effect of parenthood on drinking (Wolfe 2009). This indicates that maternal postpartum drinking patterns may be characterized by intra-individual differences in inter-individual change. However, to date, most empirical studies have measured maternal postpartum drinking information at a single point-in-time, usually short of 1 year postdelivery follow-up (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007b; Laborde and Mair 2012; McLeod et al. 2002), with some exceptions (Bailey et al. 2008; Wolfe 2009). To our knowledge, no study has assessed maternal drinking over the potentially stressful period of parenting until children enter kindergarten.

A further concern is that most studies of postpartum maternal drinking focus on mothers within a narrow age range, such as adolescence (Spears et al. 2010) and young adulthood (Bailey et al. 2008). Studies which included mothers from a wider age range (e.g. ages 18–48 in (Laborde and Mair 2012)), tended to model age as an exogenous variable. Consequently, pooling together such a wide age range may mask developmentally significant differences in patterns of postpartum drinking as well as the potentially differential effect of risk factors on these age-stratified drinking patterns. Life course theories have emphasized that the timing of transitional events matters. For example, off-time events may not have the same protective effect as on-time events (Rutter 1996). Following this logic, it would suggest that women who give birth outside the normative age range may not experience beneficial effects, such as reduction in substance use, to the same extent as those who gave birth within the normative age range. In addition, challenges involved with transitions to parenthood may vary for mothers in different age groups (McKee and Weinberger 2013). While normally considered “off-time” for pregnancy (Osterman et al. 2011), mothers older than 35 may benefit from socioeconomic factors, psychological hardiness, and some partner relationship characteristics that would facilitate the healthy transition to parenthood and may constitute protective factors for maternal mental and physical health outcomes (McMahon et al. 2011). Consequently, age-related characteristics may moderate the relationship between childbirth/parenting and health outcomes. Empirical evidence suggests that developmental patterns of perinatal alcohol consumption indeed vary as a function of maternal age at childbirth. For example, when compared to their younger counterparts, older mothers are more likely to drink during pregnancy (Meschke et al. 2008), but are less likely to drink alcohol within a short period after delivery (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007b). Limited evidence has found that age moderates the effect of risk factors on maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy. For example, marital status has a protective effect on the consumption of alcohol, but only for mothers who gave birth between age 20 and 25 (Meschke et al. 2013). In addition, research has found that maternal age at birth moderates the effect of maternal pregnancy drinking on child neurobehavioral outcomes. Specifically, the negative impact of binge drinking during pregnancy on child outcomes is greater among children of older mothers (Chiodo et al. 2010). It was speculated that older mothers are more likely to have been drinking over a longer time period and, due to a higher ratio of body fat to water in older mothers, both mother and fetus may be exposed to higher peak blood alcohol concentration.

Present Study

In sum, we have identified two important gaps in the literature on maternal postpartum alcohol consumption: 1) the majority of past studies examined postpartum drinking at a single point-in-time within a short period postdelivery and 2) most of studies focus either on mothers within a narrow age range or included mothers of a wider age range and simply examined age as a covariate, masking important age-related differences in patterns of postpartum drinking and different risk factors by maternal age interactions.

In an attempt to address these gaps, our analyses are conducted for three predefined maternal age groups (ages 20–25; ages 26–35; ages 36+), allowing for the detection of age-specific differences between the three groups. Our categorization of age is based on theoretical reasoning as well as the empirical distribution of the sample. It is also consistent with past studies on maternal substance use and reflects typical approaches of grouping age in pregnancy-related studies (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007b; Meschke et al. 2013; Turney 2012). Giving birth during emerging adulthood (ages 20–25) may coincide with education developments for some, and new and thus potentially less stable employment situations for others (Arnett 2000). Over 75 % of all births in the US are to women aged 20–34 (Osterman et al. 2011). In addition, consistent evidence showed that women over 35 have a higher risk of birth complications, such as low birth weight and premature delivery (Lisonkova et al. 2010). Thus, births to mothers ages 35 and older coincide with obstetric guidelines to undergo different tests, contributing to a cultural awareness that this is a different stage in reproductive life to be giving birth and impacting maternal behavioral choices. The authors have also considered several alternatives to this operation: a) using age merely as a covariate, b) using a finer categorization such as grouping age into 5-year categories. However, they were deemed less appropriate because using age as a covariate would mask the age-moderating effect (as discussed above), and a finer categorization of age would substantially reduce the sample sizes, thereby compromising the statistical power of the study.

Three research aims are proposed: (a) What are the population average patterns of drinking for the three groups of mothers who gave birth at different ages; (b) Are there distinct longitudinal trajectories of maternal postpartum drinking within these three age groups and do these trajectories of maternal postpartum drinking differ by age groups; and (c) Do individual characteristics before, during, or shortly after pregnancy predict these patterns differentially across the age groups? The finding of different patterns across the age groups will help identify which mothers are potentially at greater risk of problem drinking behavior. The finding of different risk factors’ association with maternal alcohol use for different age groups will determine the extent to which prevention programs have to be tailored to different age groups in order to address different individual needs and circumstances.

Methods

Sample

This study uses data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, a national survey that followed a cohort of mothers who gave birth between 1998 and 2000, representing births in all US cities with a population of 200,000 or more. A sample of 4898 new mothers from 20 citiesFootnote 1 were interviewed immediately after giving birth (baseline) and re-interviewed when their babies were 1, 3 and 5 years old. We initially included 4270 mothers who participated in the first follow-up interview. We excluded 100 cases with missing covariate information and 773 mothers who had not attained the US legal drinking age by the 1-year follow-up (i.e., age at delivery below 20 and age at year 1 interview below 21), as illegal alcohol use by mothers under the age of 21 might indicate other aspects of psychopathology, which would confound the assessment of drinking patterns among mothers 21 or older. Our final sample consists of 3397 mothers who gave birth at age 20 or older (see Table 1 for a description of the sample). To investigate variation in maternal drinking patterns across the adult reproductive years, the sample is segmented by maternal age at childbirth (1717 ages 20–25; 1367 ages 26–35; 313 ages 36+) based on reasons discussed above. Complex sampling design was accounted for by computing robust standard errors using a sandwich estimator (White 1980), and results are weighted to represent births in all US cities with a population of 200,000 or more between 1998 and 2000.

Latent Class Indicator Variables

At each of the three follow-up interviews, mothers were asked to report their drinking and binge drinking (defined as four or more drinks on a single occasion) during the past 12 months. Studies have shown that reports of postpartum behavior are less subject to the potential biases colored by awareness of the social desirability of alcohol use during pregnancy (Alvik et al. 2006). A three-level ordered categorical variable was created for each wave no alcohol (0); <4 drinks per occasion, i.e., drank but never binge drank (1); and 4+ drinks on occasion, i.e., ever binge drank (2).

Exogenous Variables

Studies of maternal drinking suggest that white, unmarried, higher income, and employed mothers are at greater risk for postpartum alcohol use (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007b; Muhuri and Gfroerer 2009). Maternal sociodemographic information and their substance use during pregnancy were collected at baseline, with categorization for this study consistent with other research. Mother’s race was coded as white (1) or non-white (0) (Ebrahim and Gfroerer 2003). Household income was constructed by dividing mother’s household income by poverty thresholds, dichotomized as greater (1) or less than (0) 185 % of the federal poverty threshold (Laraia et al. 2007). Mother’s education at baseline was dichotomized as college or graduate degree (1) or less than college degree (0) (Breslow et al. 2007). Baseline marital status was coded as married (1) or otherwise (0) (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007b). Past year employment status at baseline was dichotomized as employed (1) or not (0) (Tsai et al. 2007). In addition to these demographics, other risk factors commonly examined by past studies include postpartum depression (Homish et al. 2004), breastfeeding (Breslow et al. 2007; Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007a), and smoking during the perinatal period (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007a). At the 1 year follow-up, mother’s postpartum depression status was assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF), Section A (Kessler et al. 1998), the items therein being consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association 1994). Mothers who had depressive symptoms that lasted most of the day and occurred every day for at least two weeks met the diagnostic criteria for depression (coded 1) (Walters et al. 2002), consistent with other research (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007b). We also include smoking (coded 1) and alcohol use (coded 1) during pregnancy, queried at the baseline interview (Ethen et al. 2009), and whether they ever breastfed the child (coded 1) inquired at the 1-year interview (Giglia et al. 2007). While it is a common concern that women under-report their substance use during pregnancy, studies show that retrospective self-reports of pregnancy substance use (as in FFCW) are fairly valid and reliable (Alvik et al. 2006; Heath et al. 2003).

Analytic Plan

Longitudinal Latent Class Analysis

Longitudinal latent class analysis (LLCA), a method often used to study heterogeneity in development of substance use and related behavior (Feldman et al. 2009; Lanza and Collins 2006; Liu et al. 2013), was applied to examine the longitudinal pattern of maternal drinking/binge drinking in early parenthood. Similar to growth mixture modeling, LLCA uses a latent class variable to represent subpopulations of individuals that are similar with regard to their outcome patterns over time (see Fig. 1). However, unlike GMM, LLCA models do not place any functional form on the intra-individual change process across time within the latent classes. Instead, the latent classes are characterized directly by the item response probabilities for the repeated measures. The rationale for using LLCA to characterize alcohol consumption is that we believe the development of alcohol use at the individual level is unlikely to be described by a simple continuous function of time, even within latent classes, as would be assumed by the use of growth factors within class. LLCA, by not placing any constraints on the individual-level change patterns within class, has much greater flexibility to accommodate the discontinuous patterns of persistence, and desistence of use that are present in the data.

Class Enumeration and Regression Analysis

Deciding on the number of longitudinal latent classes is based on substantive evaluation of the classes as well as fit statistics for non-nested models, such as the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT; a significant p value indicates that the model with K-1 number of classes can be rejected in favor of the model with K number of classes) (Lo et al. 2001). BIC was given particular emphasis since it was found to outperform other criteria (Nylund et al. 2007). Upon finalizing class enumeration, we re-estimated the preferred LCA model and simultaneously regressed class on exogenous variables via multinomial logistic regression equations (Long and Cheng 2004). All covariates were included simultaneously in a multivariate model, and odds ratio for each covariate adjusting for the effects of other covariates was reported. Separate LLCA and regression models were carried out for each age group. All analyses were conducted using Mplus version 6.12 (Muthén and Muthén 1998-2012).

Missing Data

Missing data on the drinking measures were accounted for by using the widely accepted full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation method (Arbuckle 1996; Schafer and Graham 2002). In our sample, (n = 3,397 mothers), more than 80 % in each age group had valid data for all three drinking measures, and the bivariate coverageFootnote 2 was greater than 0.8 for each age group. Missing at random (MAR), i.e., missingness in alcohol measures can be related to observed measures but not to missing data (Schafer and Graham 2002), is assumed.

Results

Patterns of Alcohol Use Across Three Age Groups

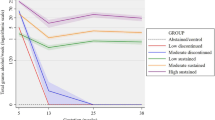

Table 1 presents the weighted distribution of alcohol consumption across the three age groups. Different patterns of drinking and binge drinking emerge when comparing these three age groups. Mothers ages 36 and older reported pregnancy drinking at more than twice the rate of mothers ages 26–35 and more than triple the rate of mothers ages 20–25. At 1 year after delivery, while older mothers are more likely to drink than younger mothers (22.1 % for age group 20–25, 33.4 % for age group 26–35; 37.5 % for age group 36+), younger mothers are more than twice as likely to engage in binge drinking (6.8 % for age group 20–25 vs. 3.3 % for age group 26–35 and 2.7 % for age group 36+). This pattern reversed given additional years postpartum. In particular, whereas binge drinking rates appear to remain stable (with a slight increase) over the 5-year post-delivery for mothers who gave birth in their early twenties (8.4 % in year 3 and 8.3 % in year five reported binge drinking), our estimates suggest that mothers ages 26 and older increasingly engaged in binge drinking over time, surpassing the binge drinking behavior of younger mothers (age group 26–35, 5.5 % in year 3 and 9.3 % in year 5; age group 36+, 18.4 % in year 3 and 26.6 % in year 5).

Deciding on the Number of Longitudinal Latent Classes

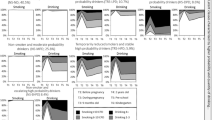

Fit indices for models with different numbers of classes are presented in Table 2. Based on statistical criteria as well as substantive considerations, a 2-class model was selected for age group 20–25 (LL = −3745.82 (13), BIC = 7588.46), and a 3-class model was selected for both age group 26–35 (LL = −2720.90 (20), BIC = 5586.22) and age group 36+ (LL = −639.89 (20), BIC = 1394.70). For each of the three age groups, we present graphs of the structure for each class, representing the three drinking categories (no alcohol, <4 drinks per occasion, 4+ drinks on occasion; see Fig. 2). A “LL (low-level)-drinkers” class was identified for all three age groups, with comparable class proportions (ages 20–25, 52.7 %; ages 26–35, 52.1 %; ages 36+, 45.9 %). LL-drinkers across the age groups have about 20 % or less probability of drinking throughout the study period. Also across age groups, a class of mothers was identified with a high probability of reported alcohol consumption, increasing over time, but a low probability of meeting the criteria for binge drinking during the specified period. This class is referred to as “NB (non-binge)-drinkers”. The NB-drinkers class encompassed 47.3 % of mothers who gave birth between ages 20 and 25. A similar proportion of mothers who gave birth between ages 26 and 35 were classified as NB-drinkers (43.2 %). For mothers who gave birth after age 36, the proportion of NB-drinkers is lower (32.1 %) than the comparison age groups.

For mothers ages 26 or older, a third class was found characterized by a high propensity for binge drinking behavior, albeit with variation in the pattern of binge drinking over the study period. Among mothers who gave birth between ages 26 and 35, 4.7 % displayed a steadily increasing probability of binge drinking over time, where the probability of no alcohol use is near zero after the first year of parenting, and the probability of binge drinking is over 0.8 by the five-year follow-up. Thus the “26–35 binge drinkers” are characterized by a relatively early onset of binge drinking behavior. By contrast, the “36+ binge drinkers,” a classification that encompassed as much as 22 % of this age group, featured a later onset of binge drinking risk after giving birth, followed by a sharp increase over the study period.

Covariate Effects for Three Age Groups

Table 3 presents the effect of covariates as an odds ratio on the probability of being in the “binge drinkers” class and the “NB-drinkers” class with the “LL-drinkers” class as the reference. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR), significance level, and 95 % confidence intervals for each effect estimated are presented, with an AOR greater than 1 representing increasing log odds of being assigned to a given class compared to the reference class (Long 1997). As shown in the table, the significance level and magnitude of these effects appear to be different across age groups. For example, while being married at the time of giving birth had a protective effect on drinking for the youngest age group by reducing the odds of drinking by nearly 80 % (AOR = 0.24; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.13, 0.47), such an effect failed to reach the 0.05 significance level for the other two age groups. Interestingly, while depression significantly increases the odds of regular drinking by over threefold for the youngest age group (AOR = 3.55; 95% CI = 1.12, 11.29) and significantly increases the odds of binge drinking by over 40-fold for the oldest age group (AOR = 41.18; 95% CI = 8.37, 202.65), it failed to have a significant impact on drinking for those mothers who gave birth between the age of 26 and 35. Drinking alcohol during pregnancy significantly increases the likelihood of NB-drinking for all age groups and binge drinking for mothers ages 26–35. Income was found to have a significant impact for the two lower age groups. Specifically, having a household income higher than 185 % poverty line increases the likelihood of being in the drinking class by fivefold (AOR = 5.22; 95 % CI = 3.00,9.06) and increases the odds of being in the binge drinking class by nearly 12 times (AOR = 11.73; 95% CI = 1.45,94.67).

Discussion

Maternal alcohol consumption during postpartum and early parenting periods poses a risk for maternal and child health. This study fills the void that we know little about maternal alcohol use beyond a few months immediately postdelivery, as a crucial first step for the development of effective prevention programs targeting this behavior. Using a sample representative of mothers in medium and large US cities, we examined the developmental patterns of maternal postpartum alcohol consumption in the context of maternal age during a potentially stressful period of parenting children until they enter kindergarten. Methodologically, this study illustrates the utility of stratifying analyses to capture differential effects of personal and social characteristics by maternal age and of capturing patterns extending for longer periods beyond childbirth. We found that mothers across age groups returned to increased drinking and/or binge drinking after delivery of a child (with some exceptions), consistent with the literature (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007b). The overall estimates of drinkers and binge drinkers are consistent with estimates in similar samples (Bailey et al. 2008; Laborde and Mair 2012). Furthermore, younger mothers were more likely to binge drink soon after their child was born—consistent with past findings (Laborde and Mair 2012)—but stabilized this behavior over time, whereas binge drinking among older mothers increased and subsequently exceeded that of the younger mothers over the early parenting period. Whether this behavioral pattern is related to the timing of the pregnancy in the mother’s reproductive career or to a cohort effect or missing confounder is not known. Nevertheless, this behavioral pattern has important prevention implications for family support and clinical care, in that greater attention is warranted for alcohol consumption among older mothers postpartum.

We found that postpartum depression was significantly associated with NB-drinking for mothers who gave birth between ages 20 and 25 and with binge drinking for those who gave birth after age 35. By contrast, the relationship was not significant for mothers ages 26 to 35. We speculate two reasons for this finding: First, mothers who give birth between ages 26–35 (as a more normative timing of pregnancy) have more social support (Landale and Oropesa 2001) that may serve as a buffer to prevent them from engaging in risky drinking and provide remedies to postpartum depression. Further, women of different ages differ in their decision to seek professional care for their depression (McIntosh 1993). Second, the frequency and persistence of postpartum depression varies by age (Horwitz et al. 2009), and future studies should examine how different aspects of depression, such as frequency of depression episodes, influence the consumption of alcohol.

Our age-stratified analyses revealed a strong association between pregnancy smoking and postpartum drinking only for mothers ages 20–25 (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007a; Laborde and Mair 2012). It is possible that smoking during pregnancy represents a lifestyle correlated with risky attitudes and behaviors for younger mothers more so than for their older counterparts. Several other determinants of maternal alcohol use were also found to be significantly associated with maternal postpartum drinking at least for some age groups. For example, consistent with other research (Jagodzinski and Fleming 2007a), we found that marriage offers a protective effect against NB-drinking postpartum for mothers ages 20–25, but is unrelated to NB-drinking or binge drinking for older mothers. Our data also indicates that higher income is a risk factor for NB-drinking by mothers ages 20–25 and for binge drinking by mothers ages 26–35. Thus, while past studies have documented a positive association between income and alcohol consumption (Ethen et al. 2009; Laborde and Mair 2012), our research suggests that this risk factor may be most relevant to mothers ages 20–35.

Limitations

We note several limitations. First, we have limited information on mothers’ alcohol-related attitudes and intentions which may predict drinking during pregnancy and postpartum drinking (Duncan et al. 2012). Second, the measure of depression in our study does not distinguish postpartum depression from depression measured at other timepoints, although a distinction is oftentimes drawn in both research and practice. However, postpartum depression is not recognized as an official diagnosis by DSM-IV-R, and evidence has shown that depression after childbirth does not differ qualitatively from occurrences at other times (Whiffen and Gotlib 1993). Third, given that the exact timing of subsequent pregnancies was not reported in the FFCW data, future research using other data is needed to distinguish to what extent subsequent pregnancies impact recent mother’s drinking behavior. In this study, we explored the effect of subsequent pregnancies in a sensitivity analysis. Results did not change substantially (available upon request). Last, our results are only representative of recent mothers in larger US urban areas.

Implications

Important prevention implication can be drawn from the results of this study. First, while alcohol consumption during pregnancy may indicate a lack of knowledge about the potential health consequences for mother and child, excessive postpartum alcohol consumption is likely to indicate poor parenting skills and/or a weak social support system to deal with new social expectations and stressors. Different prevention strategies need to be developed in order to tackle postpartum and early parenthood alcohol consumption by enhancing social support systems and promoting healthy ways of dealing with stressors associated with increased responsibilities of caring for a young child. For example, one possible approach to prevent ongoing maternal and child health risks due to excessive alcohol consumption, would be to adapt David Old’s Nurse and Family Partnership (NFP; an evidence-based program to reduce maternal prenatal substance use including alcohol), to target the general population of women, or women identified as trying to conceive and those caring for young children, in addition to the original prevention services for high risk pregnant women. Such prevention efforts represent a crucial step in the promotion of maternal and child physical and mental well-being outside of the commonly targeted 9-month pregnancy period. Second, distinctions in the risk factors for maternal postpartum drinking patterns by maternal age may be used to inform screening and targeting services for new mothers. Tobacco use during pregnancy and postpartum depression may be used for screening (McKee and Weinberger 2013) and coordinated treatment purposes among pregnant women and mothers who recently gave birth (Fowles et al. 2012). At least 10–15 % of mothers experience postpartum depression and, for recent mothers, untreated depression can lead to alcohol abuse (Toohey 2012). Although the prevalence of depression among recent mothers declines with age (Turney 2012), the strong association of depression and binge drinking among older mothers has important clinical implications. Finally, clinical prevention and treatment guidelines should reflect the increased risk of binge drinking for older mothers, who account for an increasing share of the national pregnancy rate (Ventura et al. 2012). This is important particularly given neurobehavioral problems associated with prenatal alcohol exposure for children born to older mothers (Chiodo et al. 2010).

Notes

Austin, TX; Baltimore, MD; Boston, MA; Chicago, IL; Corpus Christi, TX; Indianapolis, IN; Jacksonville, FL; Nashville, TN; New York, NY; Norfolk, VA; Philadelphia, PA; Pittsburgh, PA; Richmond, VA; San Antonio, TX; San Jose, CA; Toledo, OH; Detroit, MI; Milwaukee, WI; Newark, NJ; Oakland, CA; and Jacksonville, FL.

Bivariate coverage measures the coverage of the data points between two variables. For example, a bivariate coverage of 0.996 between drinking measured at year 1 and that measure at year 3 indicates that 99.6 % of the sample has valid measures of drinking at both time points. A bivariate coverage higher than 0.1 is necessary for efficient FIML estimation. In this sample, the bivariate coverage is greater than 0.8 for all three age groups, which indicates sufficiently high coverage.

References

Alvik, A., Haldorsen, T., Groholt, B., & Lindemann, R. (2006). Alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy comparing concurrent and retrospective reports. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 30, 510–515. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00055.x.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic criteria from DSM-IV. USA: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.

Arbuckle, J. L. (1996). Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In G. A. Marcoulides & R. E. Schumacker (Eds.), Advanced structural equation modeling: issues and techniques (pp. 243–277). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood—a theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Bailey, J. A., Hill, K. G., Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Abbott, R. D. (2008). Men’s and women’s patterns of substance use around pregnancy. Birth, 35, 50–59. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2007.00211.x.

Breslow, R. A., Falk, D. E., Fein, S. B., & Grummer-Strawn, L. M. (2007). Alcohol consumption among breastfeeding women. Breastfeeding Medicine, 2, 152–157.

Chiodo, L. M., Da Costa, D. E., Hannigan, J. H., Covington, C. Y., Sokol, R. J., Janisse, J., & Delaney-Black, V. (2010). The impact of maternal age on the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on attention. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 34, 1813–1821. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01269.x.

Duncan, E. M., Forbes-McKay, K. E., & Henderson, S. E. (2012). Alcohol use during pregnancy: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42, 1887–1903. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00923.x.

Ebrahim, S. H., & Gfroerer, J. (2003). Pregnancy-related substance use in the United States during 1996–1998. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 101, 374–379.

Ethen, M., Ramadhani, T., Scheuerle, A., Canfield, M., Wyszynski, D., Druschel, C., & Romitti, P. (2009). Alcohol consumption by women before and during pregnancy. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13, 274–285. doi:10.1007/s10995-008-0328-2.

Fan, A. Z., Russell, M., Naimi, T., Li, Y., Liao, Y., Jiles, R., & Mokdad, A. H. (2008). Patterns of alcohol consumption and the metabolic syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 93, 3833–3838. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-2788.

Feldman, B. J., Masyn, K. E., & Conger, R. D. (2009). New approaches to studying problem behaviors: a comparison of methods for modeling longitudinal, categorical adolescent drinking data. Developmental Psychology, 45, 652–676.

Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., & John Horwood, L. (2012). Transition to parenthood and substance use disorders: findings from a 30-year longitudinal study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 125, 295–300. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.03.003.

Fleming, M. F., Lund, M. R., Wilton, G., Landry, M., & Scheets, D. (2008). The Healthy Moms study: The efficacy of brief alcohol intervention in postpartum women. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 1600–1606. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00738.x.

Fowles, E. R., Cheng, H. R., & Mills, S. (2012). Postpartum health promotion interventions a systematic review. Nursing Research, 61, 269–282. doi:10.1097/NNR.0b013e3182556d29.

Giglia, R. C., Binns, C. W., Alfonso, H. S., & Zhan, Y. (2007). Which mothers smoke before, during and after pregnancy? Public Health, 121, 942–949. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2007.04.007.

Heath, A. C., Knopik, V. S., Madden, P. A., Neuman, R. J., Lynskey, M. J., Slutske, W. S., & Martin, N. G. (2003). Accuracy of mothers’ retrospective reports of smoking during pregnancy: comparison with twin sister informant ratings. Twin Research and Human Genetics, 6, 297–301.

Homish, G. G., Cornelius, J. R., Richardson, G. A., & Day, N. L. (2004). Antenatal risk factors associated with postpartum comorbid alcohol use and depressive symptomatology. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 28, 1242–1248. doi:10.1097/01.alc.0000134217.43967.97.

Horwitz, S. M., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., Storfer-lsser, A., & Carter, A. S. (2009). Persistence of maternal depressive symptoms throughout the early years of childhood. Journal of Women’s Health, 18, 637–645. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1229.

Jagodzinski, T., & Fleming, M. F. (2007a). Correlates of postpartum alcohol use. Wisconsin Medical Journal, 106, 319–325.

Jagodzinski, T., & Fleming, M. F. (2007b). Postpartum and alcohol-related factors associated with the relapse of risky drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68, 879–885.

Jester, J. M., Jacobson, S. W., Sokol, R. J., Tuttle, B. S., & Jacobson, J. L. (2000). The influence of maternal drinking and drug use on the quality of the home environment of school-aged children. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 24, 1187–1197. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02082.x.

Jonas, D. E., Garbutt, J. C., Amick, H. R., Brown, J. M., Brownley, K. A., Council, C. L., & Harris, R. P. (2012). Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the us preventive services task force. Annals of Internal Medicine, 157, 645–654.

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Mroczek, D., Ustun, B., & Wittchen, H. U. (1998). The world health organization composite international diagnostic interview short‐form (cidi‐sf). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7, 171–185.

Laborde, N., & Mair, C. (2012). Alcohol use patterns among postpartum women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16, 1810–1819. doi:10.1007/s10995-011-0925-3.

Landale, N. S., & Oropesa, R. S. (2001). Migration, social support and perinatal health: an origin-destination analysis of Puerto Rican women. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42, 166–183. doi:10.2307/3090176.

Lanza, S. T., & Collins, L. M. (2006). A mixture model of discontinuous development in heavy drinking from ages 18 to 30: the role of college enrollment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 67, 552–561.

Laraia, B., Messer, L., Evenson, K., & Kaufman, J. S. (2007). Neighborhood factors associated with physical activity and adequacy of weight gain during pregnancy. Journal of Urban Health-Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 84, 793–806. doi:10.1007/s11524-007-9217-z.

Lisonkova, S., Janssen, P. A., Sheps, S. B., Lee, S. K., & Dahlgren, L. (2010). The effect of maternal age on adverse birth outcomes: does parity matter? Journal of Obstet Gynaecol Canada, 32, 541–548.

Little, R. E., Lambert, M. D., & Worthington-Roberts, B. (1990). Drinking and smoking at 3 months postpartum by lactation history. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 4, 290–302. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.1990.tb00653.x.

Liu, W., Lynne-Landsman, S., Petras, H., Masyn, K., & Ialongo, N. (2013). The evaluation of two first-grade preventive interventions on childhood aggression and adolescent marijuana use: a latent transition longitudinal mixture model. Prevention Science, 14, 206–217. doi:10.1007/s11121-013-0375-9.

Lo, Y. T., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88, 767–778. doi:10.1093/biomet/88.3.767.

Long, J. S. (1997). Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables (Vol. 7). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Incorporated.

Long, J. S., & Cheng, S. (2004). Regression models for categorical outcomes. In M. Hardy & A. Bryman (Eds.), Handbook of data analysis (pp. 259–284). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd.

McIntosh, J. (1993). Postpartum depression: women's help-seeking behaviour and perceptions of cause. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 18, 178–184. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1993.18020178.x.

McKee, S. A., & Weinberger, A. H. (2013). How can we use our knowledge of alcohol-tobacco interactions to reduce alcohol use? Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 649–674. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185549.

McLeod, D., Pullon, S., Cookson, T., & Cornford, E. (2002). Factors influencing alcohol consumption during pregnancy and after giving birth. New Zealand Medical Journal, 115(1157), U29.

McMahon, C. A., Boivin, J., Gibson, F. L., Hammarberg, K., Wynter, K., Saunders, D., & Fisher, J. (2011). Age at first birth, mode of conception and psychological wellbeing in pregnancy: findings from the parental age and transition to parenthood Australia (PATPA) study. Human Reproduction, 26, 1389–1398. doi:10.1093/humrep/der076.

Meschke, L. L., Hellerstedt, W., Holl, J. A., & Messelt, S. (2008). Correlates of prenatal alcohol use. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 12, 442–451. doi:10.1007/s10995-007-0261-9.

Meschke, L. L., Holl, J., & Messelt, S. (2013). Older not wiser: risk of prenatal alcohol use by maternal age. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17, 147–155. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-0953-7.

Meyer-Leu, Y., Lemola, S., Daeppen, J.-B., Deriaz, O., & Gerber, S. (2011). Association of moderate alcohol use and binge drinking during pregnancy with neonatal health. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research, 35, 1669–1677. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01513.x.

Muhuri, P. K., & Gfroerer, J. C. (2009). Substance use among women: associations with pregnancy, parenting, and race/ethnicity. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 13, 376–385. doi:10.1007/s10995-008-0375-8.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus (Version 6.12). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14, 535–569. doi:10.1080/10705510701575396.

Olds, D. L., Robinson, J., O’Brien, R., Luckey, D. W., Pettitt, L. M., Henderson, C. R., & Hiatt, S. (2002). Home visiting by paraprofessionals and by nurses: a randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics, 110, 486–496.

Osterman, M. J., Martin, J. A., & Menacker, F. (2011). Expanded data from the new birth certificate, 2008. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Rutter, M. (1996). Transitions and turning points in developmental psychopathology: as applied to the age span between childhood and mid-adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 19, 603–626. doi:10.1177/016502549601900309.

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177.

Spears, G. V., Stein, J. A., & Koniak-Griffin, D. (2010). Latent growth trajectories of substance use among pregnant and parenting adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24, 322–332. doi:10.1037/a0018518.

Staff, J., Greene, K. M., Maggs, J. L., & Schoon, I. (2014). Family transitions and changes in drinking from adolescence through mid-life. Addiction, 109, 227–236. doi:10.1111/add.12394.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2011). Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k10NSDUH/2k10Results.pdf.

Toohey, J. (2012). Depression during pregnancy and postpartum. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 55, 788–797. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e318253b2b4.

Tsai, J., Floyd, R. L., Green, P. P., & Boyle, C. A. (2007). Patterns and average volume of alcohol use among women of childbearing age. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 11, 437–445.

Turnbull, C., & Osborn, D. A. (2012). Home visits during pregnancy and after birth for women with an alcohol or drug problem. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004456.pub3

Turney, K. (2012). Prevalence and correlates of stability and change in maternal depression: evidence from the fragile families and child wellbeing study. PLoS ONE, 7(9), e45709. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045709.

Ventura, S. J., Curtin, S. C., Abma, J. C., & Henshaw, S. K. (2012). Estimated pregnancy rates and rates of pregnancy outcomes for the United States, 1990–2008. National Vital Statistics Reports, 60(7), 1–21.

Walters, E. E., Kessler, R. C., Nelson, C. B., & Mroczek, D. (2002). Scoring the world health organization’s composite international diagnostic interview short form (CIDI-SF). Revised December 2002. Retrieved January 17, 2005, from http://www3.who.int/cidi/CIDISFScoringMemo12-03-02.pdf

Whiffen, V. E., & Gotlib, I. H. (1993). Comparison of postpartum and nonpostpartum depression: clinical presentation, psychiatric history, and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 485–494.

White, H. (1980). A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 48, 817–838.

Wolfe, J. D. (2009). Age at first birth and alcohol use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 395–409.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grant 1 R01 DA 030496-01A1, Social Ecology of Maternal Substance Use, to principal investigator Dr. Elizabeth A. Mumford). Our thanks to Kaitlyn Krivitzky, Emily F. White, and Hannah Joseph for reviewing the literature supporting this paper and preparing the tables and figures. We also appreciate the consultations provided by Dr. Pradip Muhuri, SAMHSA, regarding estimates of similar outcomes in the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, W., Mumford, E.A. & Petras, H. Maternal Patterns of Postpartum Alcohol Consumption by Age: A Longitudinal Analysis of Adult Urban Mothers. Prev Sci 16, 353–363 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-014-0522-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-014-0522-y