Abstract

The Southeast has high rates of church attendance and HIV infection rates. We evaluated the relationship between church attendance and HIV viremia in a Southeastern US, HIV-infected cohort. Viremia (viral load ≥200 copies/ml) was analyzed 12 months after initiation of care. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models were fit for variables potentially related to viremia. Of 382 patients, 74 % were virally suppressed at 12 months. Protective variables included church attendance (AOR 0.5; 95 % CI 0.2, 0.9), being on antiretroviral therapy (AOR 0.01; 95 % CI 0.004, 0.04), CD4+ T lymphocyte count 200–350 cells/mm3 at care entry (AOR 0.3; 95 % 0.1, 0.9), and education (AOR 0.5; 95 % CI 0.2, 0.9). Variables predicting viremia included black race (AOR 3.2; 95 % CI 1.4, 7.4) and selective disclosure of HIV status (AOR 2.7; 95 % CI 1.2, 5.6). Church attendance may provide needed support for patients entering HIV care for the first time.

Resumen

El Sur Este de los Estados Unidos tiene tasas altas de visitas a iglesias y de infección por VIH. Evaluamos la relación entre visitas a iglesias y viremia por VIH en una cohorte de pacientes infectados con VIH en el Sur Este de los EEUU. La viremia (carga viral ≥ 200 copias/ml) fue analizada a los 12 meses de iniciar el cuidado médico. Los modelos de regresión logística univariado y multivariado fueron ajustados para variables potencialmente relacionadas a viremia. De 382 pacientes, 75 % tuvieron supresión virológica a los 12 meses. Variables que ofrecieron protección fueron visitas a iglesias (AOR 0.5; IC95 % 0.2-0.9), recibir terapia antiretroviral (AOR 0.01; IC95 % 0.004,0.04), recuento de linfocitos T CD4 + 200-350 al iniciar cuidado médico (AOR 0.3; IC95 % 0.1,09), y educación (AOR 0.5; IC95 % 0.2,0.9). Las variables que predijeron viremia incluyeron raza negra (AOR 3.2; IC95 % 1.4,7.4) y la comunicación selectiva del diagnóstico de VIH a otras personas (AOR 2.7; 95 % IC 1.2, 5.6). El asistir a iglesias puede proveer un suporte a los pacientes que inician cuidado médico por infección por VIH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spirituality and religion are thought to play important, yet potentially conflicting, roles in the health and health-seeking behaviors of persons living with HIV [1]. For some individuals with HIV, spirituality and religion may provide a source of support and coping, contributing to improved psychological and even physical health [1–6]. Yet for others, spirituality and religion may contribute to stress, particularly if the individual with HIV perceives that her/his religious group stigmatizes HIV or denounces the behaviors associated with HIV acquisition [7, 8]. Religious stigmatization of HIV and the behaviors associated with its acquisition, whether real or perceived, may contribute to reduced engagement in HIV screening, HIV-related medical care and antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence [1, 7, 9, 10].

The most religious region in the US is the southeast, which also represents the region most disproportionately affected by HIV [11, 12]. Our work focuses on understanding the interplay between religion and HIV in the Southeast. Previously we reported a relationship between sexual behavior, church attendance and the timing of HIV diagnosis and presentation for care. Men who acknowledged sex with men (MSM) and who reported church attendance were more likely to present with lower CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts at entry to care than MSM who did not report church attendance. This association was not found for either men who reported sex with only women (MSW) or women who reported sex with men (WSM) when stratified by church attendance [13]. Misalignment between sexual behaviors and religiously held beliefs may have hindered engagement in HIV-related screening and healthcare.

The HIV care continuum provides a framework to understand the steps of HIV care from diagnosis to the ultimate goal of HIV viral load suppression [14, 15]. With HIV viral load suppression comes preservation of the health of people living with HIV and also their reduced risk of transmission of HIV to others [16–18]. As the culmination of the HIV care continuum, we chose to evaluate the relationship between HIV viral load suppression and religious participation. Using church attendance as a marker of religious involvement, we evaluated the relationship between reported church attendance at the time of entry into HIV care and HIV viremia 12 months after initiation of HIV care.

Methods

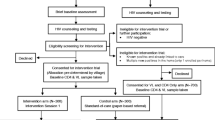

Study Design and Participants

We analyzed data from a cohort of HIV-infected persons presenting for the first time for HIV-related care at a university-based HIV Clinic (1917 Clinic). This population has been described previously [13, 19]. Patients entering HIV primary care at the clinic complete an orientation visit prior to their first medical appointment known as Project Client-Oriented New Patient Navigation to Encourage Connection to Treatment (CONNECT). Project CONNECT is an intervention where recently diagnosed HIV patients have a scheduled orientation visit within 5 days of their initial call to the clinic. During this orientation visit, the Project CONNECT facilitator builds rapport with the new patient. The patient undergoes a semi-structured interview, completes a psychosocial questionnaire, and undergoes baseline laboratory testing. The information gathered through this screening is used to identify each patient’s unique needs and address them to ensure successful engagement in HIV care [20, 21]. This visit includes a self-administered questionnaire. Domains include socio-demographic characteristics, including church attendance, as well as identification of physical and emotional resources for and barriers to sustained engagement in care [20].

We included data from patients 19 years of age and older who: did not report prior history of HIV outpatient medical care; were entering care between 2007 and 2012 and; had an HIV viral load evaluated on entry to care and 12 months ± 90 days after their first clinic visit. This study was approved by the University of Alabama Institutional Review Board.

Outcome Variable

The primary outcome was viral load 12 months ± 90 days from the time of entry into HIV care for the first time. HIV viral load was categorized as a 2-level variable: suppressed and detectable viremia. The threshold for suppressed HIV viral load was set at <200 copies/ml. This value was chosen to allow for modest elevations in viral load that can be observed even in ART adherent patients [22].

Independent Variables

Church attendance was the principal independent variable of interest. All patients are asked, “Do you currently attend a church, synagogue, or mosque?” Participants may answer (1) yes, current attendance, (2) no, but past attendance, or (3) no, never attended. Church attendance was analyzed as a 2-level variable: current church attendance compared to past church attendance or never attending church. By combining groups in this manner we were able to compare current church attendance to current nonattendance. The rationale for this dichotomy was our belief that the influences (social, spiritual, organizational, etc.) that religion may have on viral load suppression would be greatest for persons actively engaged in religious activity. Participants who answered yes to this question were almost exclusively affiliated with Christian religions. Church attendance was evaluated in the context of other variables shown to associate with viremia [13, 19, 23–25]. These included: race (Black American, Caucasian, and other); age (continuous), sex and sexual behavior (MSM, MSW, WSM); CD4+ T lymphocyte count ± 90 days of entry into care (>350, 200–350, <200 cells/mm3); initiation of ART within 12 months of their first primary care visit (yes, no); education (diploma/GED or less, some college or more); and insurance status (private, none, public). Because engagement in care is closely linked to ART adherence and viral load suppression, we also included consistent care as an independent variable [26]. Consistent care was defined as no gaps of >180 days between primary care visits. In addition, living arrangement (alone, with family, with a partner/spouse/significant other (SO), friends/other) and disclosure of HIV status at the time of entry into care (no one, one disclosure group, more than one disclosure group) were included in models based on our recent work demonstrating a relationship between HIV disclosure and consistent engagement in HIV care [27].

Statistical Analysis

Independent variables were summarized using frequencies and percent for categorical variables and medians, with lower and upper quartiles, for continuous variables. Logistic regression models modeling viral load at 12 months were fit with detectable as the event. Univariate models were first fit and variables with p-values less than 0.10 as well as variables of particular interest were considered for multivariable models. Adjusted odds ratios along with their corresponding 95 % confidence intervals are reported. Models including church attendance by sexual behavior interaction term were also fit to evaluate the potential interaction between church attendance and sexual behavior. All analyses were performed using SAS v9.3 (Cary, NC).

Results

Population Characteristics

A total of 382 patients entered HIV care for the first time, completed a Project CONNECT visit, and had an HIV viral load available 12 months ± 90 days from the time of entry into HIV care. Median age of participants was 35 years. The majority was African American (60 %), male (84 %) and reported same sex sexual behavior as their HIV risk factor (65 %). Fifty-seven percent of the study population reported current church attendance. Most had some college education (60 %). A total of 89 % reported disclosing their HIV status to someone. The majority lived with someone (76 %) and most often with family (35 %) (Table 1).

CD4+ T lymphocyte counts <200 and <350 cells/mm3 were observed in 35 and 57 % of participants at the time of entry into care, respectively. The majority of patients were started on ART during the 1-year study period (87 %) and remained in continuous care during the 12 months following their first primary HIV care visit (81 %).

Church Attendance and Viremia

At 12 months, 74 % of patients had a suppressed HIV viral load while 26 % had detectable viremia. Church attendance was associated with reduced odds of viremia (AOR 0.5; 95 % CI 0.2, 0.9) (Table 2). Previously, we described an interaction between church attendance and sex/sexual behavior on timing of entry into HIV care [13]. No similar interaction was observed between church attendance and sex/sexual behavior and HIV viral load at 12 months (data not shown). Sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the association between church attendance and HIV viremia in the subset of patients who initiated ART during their first 12 months of care and also in the subset of those with consistent care. A significant and reduced odds of viremia in church attenders was observed in these analyses (data not shown).

Factors Associated with HIV Viremia and HIV Suppression 12 Months After Initiation of HIV Care

Other variables associated with reduced odds of HIV viremia included initiation of ART (AOR 0.01; 95 % CI 0.004, 0.04), more education (AOR 0.5; 95 % CI 0.2, 0.9), and a CD4+ T lymphocyte count at the time of entry into care between 200 and 350 cells/mm3 (AOR 0.3; 95 % CI 0.1, 0.9).

Variables associated with increased odds for HIV viremia 12 months after initiation of HIV care included African American race (AOR 3.2; 95 % CI 1.4, 7.4) and disclosure of HIV to only one group (i.e. either family, friends, or a significant other/spouse/partner) when compared to disclosure to more than one group (AOR 2.7; 95 % CI 1.2, 5.6).

Discussion

Our goal is to understand the influence of religion on the HIV experience of people living in the Southeastern US. Using the HIV care continuum as our model, we previously evaluated the relationship between church attendance and timing of HIV testing and linkage to care. We reported that HIV-infected MSM who attended church were more likely to present to HIV care with lower CD4+ T lymphocyte counts than those who did not attend church [13]. In this study, we focused on the relationship between church attendance at the time of entry into care and the final phase of the HIV-care continuum, HIV viral load suppression. We observed that persons who reported church attendance at the time of entry into HIV care had a reduced likelihood of HIV viremia 12 months later.

Our findings are congruent with other work suggesting that religion and spirituality can better the HIV experience. Early after diagnosis, religion and spirituality have been shown to serve as a source of strength and provide meaning to having HIV [6]. Subsequently, and for those who feel empowered by God to actively engage in HIV care and adhere to ART, religion and spirituality may contribute to medication adherence, HIV viral load suppression and improved health [9, 28–30]. In research on long-term survival with HIV, people with HIV often reported an increase in spirituality after HIV diagnosis, which was associated with slower disease progression [2, 31]. However, these favorable associations are mirrored by other reports of detrimental associations between religion, spirituality and HIV health. Several studies have shown lower ART adherence in persons who perceived God as in control of one’s health [32, 33]. In one cohort, those who regularly attended religious services and who reported using prayer and meditation to connect with God were also less adherent to ART [33].

Further adding to the complexity of the relationship between religion and spirituality and HIV health is the view by some religions that the behaviors associated with HIV acquisition are sinful and HIV is the punishment. Those with HIV who belong to religions that hold such beliefs (and are often internalized by the HIV positive individual) may suffer worse HIV-related health outcomes [2, 9, 34, 35]. In such cases, the religious stigmatization of HIV is likely layered on other religiously stigmatized characteristics associated with HIV such as route of HIV transmission (i.e. same sex sexual behavior and intravenous drug use) [7, 36]. This religiously introduced HIV-related stigma may compromise successful adherence to ART [36].

Our current findings, in the context of our previous work, support the belief that church attendance and by extension religion may relate to HIV in disparate ways and within the same population. As explanation, our findings may represent an evolving association between church attendance and HIV within the same individual over time. Perhaps, church attending MSM whose religion views HIV and/or same sex behavior negatively may avoid HIV screening to prevent their suffering from religious stigmatization of HIV and/or same sex behavior resulting in later presentation to care. Yet after diagnosis, as religious beliefs, religious affiliation, and level of religious engagement evolve, these same individuals may find that religion positively contributes to HIV health including HIV viral load suppression [31]. As an alternate explanation, we may have measured consistent relationships (both positive and negative) between church attendance and HIV-health within specific subgroups of our population over time. Unfortunately, our study was too small to perform subset analyses to look for such interactions. Future work will use a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to test for these possible explanations.

Our work along with the work of others suggests that the relationship one holds with his/her religion is likely complex, person-specific, and potentially plastic. Open communication between provider and patient about religious involvement as well as religiously held beliefs about HIV may lead to the provider’s better understanding of whether religion could be a facilitator or barrier to HIV-health. This may have particular relevance for practitioners who care for persons with HIV in highly religious regions such as the Southeastern US.

Our analysis also included other factors thought to potentially influence HIV viremia. Consistent with previous reports, Black Americans had higher odds of viremia than Caucasian Americans while initiation of ART and more education associated with lower odds of viremia [26, 37–39]. Reduced viremia was observed among persons with initial CD4+ T lymphocyte counts between 200 and 350 cells/mm3. This likely reflects previous HIV treatment guidelines that overlap with the study period and that supported initiation of ART at a lower CD4+ T lymphocyte count than currently recommended [40]. We also observed an association between viremia and HIV status disclosure. Although further work is needed to understand the relationship between HIV disclosure and viral load suppression, our findings are congruent with other reports that suggest that greater disclosure of HIV to supportive people may be linked to better engagement in HIV care, retention in care and receipt of ART [27, 41–44].

Our study has several limitations. Church attendance is a rudimentary measure of the complex concepts of religion and spirituality and caution is needed when interpreting our findings. We did not have information about religious affiliation, frequency of church attendance, or continuation of church attendance after baseline. Nor were we able to dissect whether religious community support and/or religious beliefs are responsible for the observed association. Further, attending church regularly may reflect greater life stability and organization, characteristics that also favor medication adherence, rather than a positive coping mechanism. Despite the limitations of this measure, asking about church attendance early in a person’s care followed by an exploration of the patient’s spiritual and religious beliefs may have practical benefit for understanding possible facilitators and barriers to HIV health.

As a retrospective study, our findings do not establish a causal relationship between independent variables and viremia. Cross-sectional measures of viremia are well established but are unlikely to fully capture viremia. Viremia copy-years, a cumulative measure of viremia over time, may provide a more accurate representation and provide improved prognostic value [44]. This study was designed to include only those patients who had a viral load available at 12 months and does not address those who fell out of care or those without a viral load available at 12 months.

Despite these limitations, our findings offer insight into the relationship between church attendance and HIV viremia at 12 months in a Southeastern US cohort. They further expose the complex relationship that religion and spirituality have with HIV health and the need for further investigation.

References

Szaflarski M. Spirituality and religion among HIV-infected individuals. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(4):324–32.

Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Fletcher MA. An increase in religiousness/spirituality occurs after HIV diagnosis and predicts slower disease progression over 4 years in people with HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 5):S62–8.

Trevino KM, Pargament KI, Cotton S, Leonard AC, Hahn J, Caprini-Faigin CA, et al. Religious coping and physiological, psychological, social, and spiritual outcomes in patients with HIV/AIDS: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):379–89.

Tsevat J, Leonard AC, Szaflarski M, Sherman SN, Cotton S, Mrus JM, et al. Change in quality of life after being diagnosed with HIV: a multicenter longitudinal study. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23(11):931–7.

Bluthenthal RN, Palar K, Mendel P, Kanouse DE, Corbin DE, Derose KP. Attitudes and beliefs related to HIV/AIDS in urban religious congregations: barriers and opportunities for HIV-related interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(10):1520–7.

Martinez J, Lemos D, Hosek S, Adolescent Medicine Trials Network. Stressors and sources of support: the perceptions and experiences of newly diagnosed Latino youth living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(5):281–90.

Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J. Homonegativity, religiosity, and the intersecting identities of young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2016; 20(1):51–64.

Balaji AB, Oster AM, Viall AH, Heffelfinger JD, Mena LA, Toledo CA. Role flexing: how community, religion, and family shape the experiences of young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(12):730–7.

Parsons SK, Cruise PL, Davenport WM, Jones V. Religious beliefs, practices and treatment adherence among individuals with HIV in the southern United States. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20(2):97–111.

Foster ML, Arnold E, Rebchook G, Kegeles SM. `It’s my inner strength’: spirituality, religion and HIV in the lives of young African American men who have sex with men. Cult Health Sex. 2011;13(9):1103–17.

Prevention CfDCa. HIV and AIDS in the United States by Geographic Distribution Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/basics/geographicdistribution.html. Updated 25 Apr 2013; cited 5 Mar 2015.

Newport F. Mississippi is most religious U.S. State www.gallup.com2012. 2012. http://www.gallup.com/poll/153479/mississippi-religious-state.aspx. Updated 27 Mar 2012; cited 5 Mar 2015].

Van Wagoner N, Mugavero M, Westfall A, Hollimon J, Slater LZ, Burkholder G, et al. Church attendance in men who have sex with men diagnosed with HIV is associated with later presentation for HIV care. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(2):295–9.

Cheever LW. Engaging HIV-infected patients in care: their lives depend on it. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(11):1500–2.

Mugavero MJ, Norton WE, Saag MS. Health care system and policy factors influencing engagement in HIV medical care: piecing together the fragments of a fractured health care delivery system. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(Suppl 2):S238–46.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Collaboration H-C, Ray M, Logan R, Sterne JA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM, et al. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24(1):123–37.

Skarbinski J, Rosenberg E, Paz-Bailey G, Hall HI, Rose CE, Viall AH, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus transmission at each step of the care continuum in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):588–96.

Elopre L, Westfall AO, Mugavero MJ, Zinski A, Burkholder G, Hook EW, et al. Predictors of HIV disclosure in infected persons presenting to establish care. AIDS Behav. 2016; 20(1):147–54.

Mugavero MJ. Improving engagement in HIV care: what can we do? Top HIV Med. 2008;16(5):156–61.

Bimringham UoAa. Becoming a new patient: UAB; [cited 2015 12/22/15]. Project CONNect site].

Garcia-Gasco P, Maida I, Blanco F, Barreiro P, Martin-Carbonero L, Vispo E, et al. Episodes of low-level viral rebound in HIV-infected patients on antiretroviral therapy: frequency, predictors and outcome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(3):699–704.

Kong MC, Nahata MC, Lacombe VA, Seiber EE, Balkrishnan R. Association between race, depression, and antiretroviral therapy adherence in a low-income population with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(9):1159–64.

Chesney MA. Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl 2):S171–6.

Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Publ Health. 2013;13:482.

Cohen SM, Hu X, Sweeney P, Johnson AS, Hall HI. HIV viral suppression among persons with varying levels of engagement in HIV medical care, 19 US jurisdictions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;67(5):519–27.

Elopre LW, Westfall AO, Mugavero M., Zinski A, Burkholder G, Hook E, Van Wagoner N, editors. The role of HIV status disclosure in retention in care and viral-load suppression. Conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections. Seatle: International Antiviral Society-USA; 2015.

Holt CL, Clark EM, Kreuter MW, Rubio DM. Spiritual health locus of control and breast cancer beliefs among urban African American women. Health Psychol. 2003;22(3):294–9.

Konkle-Parker DJ, Erlen JA, Dubbert PM. Barriers and facilitators to medication adherence in a southern minority population with HIV disease. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2008;19(2):98–104.

Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: a review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):227–45.

Kremer H, Ironson G, Kaplan L, Stuetzele R, Baker N, Fletcher MA. Spiritual coping predicts CD4-cell preservation and undetectable viral load over four years. AIDS Care. 2015;27(1):71–9.

Finocchario-Kessler S, Catley D, Berkley-Patton J, Gerkovich M, Williams K, Banderas J, et al. Baseline predictors of ninety percent or higher antiretroviral therapy adherence in a diverse urban sample: the role of patient autonomy and fatalistic religious beliefs. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25(2):103–11.

Vyas KJ, Limneos J, Qin H, Mathews WC. Assessing baseline religious practices and beliefs to predict adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons. AIDS Care. 2014;26(8):983–7.

Kremer H, Ironson G, Kaplan L. The fork in the road: HIV as a potential positive turning point and the role of spirituality. AIDS Care. 2009;21(3):368–77.

Yi MS, Mrus JM, Wade TJ, Ho ML, Hornung RW, Cotton S, et al. Religion, spirituality, and depressive symptoms in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 5):S21–7.

Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, Psaros C, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18640.

Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, Holtgrave DR, Furlow-Parmley C, Tang T, et al. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(14):1337–44.

Katz IT, Leister E, Kacanek D, Hughes MD, Bardeguez A, Livingston E, et al. Factors associated with lack of viral suppression at delivery among highly active antiretroviral therapy-naive women with HIV: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):90–9.

Shacham E, Nurutdinova D, Onen N, Stamm K, Overton ET. The interplay of sociodemographic factors on virologic suppression among a U.S. outpatient HIV clinic population. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24(4):229–35.

Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Cahn P, Montaner JS, Rizzardini G, Telenti A, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2010;304(3):321–33.

Ostermann J, Pence B, Whetten K, Yao J, Itemba D, Maro V, et al. HIV serostatus disclosure in the treatment cascade: evidence from Northern Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2015;27(Suppl 1):59–64.

Edwards LV. Perceived social support and HIV/AIDS medication adherence among African American women. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(5):679–91.

Hult JR, Wrubel J, Branstrom R, Acree M, Moskowitz JT. Disclosure and nondisclosure among people newly diagnosed with HIV: an analysis from a stress and coping perspective. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26(3):181–90.

Mugavero MJ, Napravnik S, Cole SR, Eron JJ, Lau B, Crane HM, et al. Viremia copy-years predicts mortality among treatment-naive HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(9):927–35.

Funding

Support: N.J. Van Wagoner: National Institutes of Health, 1K2323A1097267.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Van Wagoner, N., Elopre, L., Westfall, A.O. et al. Reported Church Attendance at the Time of Entry into HIV Care is Associated with Viral Load Suppression at 12 Months. AIDS Behav 20, 1706–1712 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1347-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1347-4