Abstract

We investigated the effect of early antiretroviral treatment (ART) initiation on HIV status disclosure and social support in a cluster-randomized, treatment-as-prevention (TasP) trial in rural South Africa. Individuals identified HIV-positive after home-based testing were referred to trial clinics where they were invited to initiate ART immediately irrespective of CD4 count (intervention arm) or following national guidelines (control arm). We used Poisson mixed effects models to assess the independent effects of (a) time since baseline clinical visit, (b) trial arm, and (c) ART initiation on HIV disclosure (n = 182) and social support (n = 152) among participants with a CD4 count > 500 cells/mm3 at baseline. Disclosure and social support significantly improved over follow-up in both arms. Disclosure was higher (incidence rate ratio [95% confidence interval]: 1.24 [1.04; 1.48]), and social support increased faster (1.22 [1.02; 1.46]) in the intervention arm than in the control arm. ART initiation improved both disclosure and social support (1.50 [1.28; 1.75] and 1.34 [1.12; 1.61], respectively), a stronger effect being seen in the intervention arm for social support (1.50 [1.12; 2.01]). Besides clinical benefits, early ART initiation may also improve psychosocial outcomes. This should further encourage countries to implement universal test-and-treat strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Early initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in people living with HIV (PLHIV) (i.e., ART initiation when CD4 count is high and before symptom onset) preserves immune function, reduces morbidity and increases life expectancy [1, 2]. It also increases viral suppression at 12 months [3], which reduces the risk of HIV transmission to sexual partners [4, 5].

Over the last 10 years, evidence for the clinical benefits of early ART initiation has led the World Health Organization (WHO) to update its treatment initiation recommendations: from a CD4 count of ≤ 350 cells/mm3 in 2010 [6] to ≤ 500 cells/mm3 in 2013 [7], to initiation irrespective of CD4 count in 2015 [8].

In addition, as suggested by modelling and observational studies [9,10,11], early ART may have the potential to decrease HIV incidence at the population level. In this context, several large-scale trials in HIV hyper-endemic areas, including the ANRS 12249 TasP trial in South Africa [12], have been implemented to assess whether adopting a universal test-and-treat (UTT) strategy (i.e., regular and wide-ranging universal testing campaigns with HIV treatment offered immediately after HIV diagnosis, irrespective of CD4 count) might led to reduced HIV incidence in the general population [13,14,15]. While recent results from these trials all showed an increase in the proportions of PLHIV with viral suppression, only two trials saw a reduction in HIV incidence at the population level [13, 16, 17]. Apart from reducing HIV incidence, the implementation of a UTT strategy also raises questions about the psychosocial implications of early ART initiation.

Data in the literature on the psychosocial effects of early ART initiation is scarce, both at the individual and community levels. Two psychosocial outcomes are of particular importance in this context: HIV disclosure and social support The latter can be defined as supportive acts by a partner(s) and loved ones which are either emotional (showing understanding, love and care), or instrumental (providing advice or material/financial help) [18, 19]. HIV disclosure to loved ones is itself associated with greater social support [18]. Both outcomes are predictors of higher ART adherence, improved clinical outcomes [18, 20] and quality of life [18, 21], as well as reduced stigma [22].

As ART initiation facilitates HIV status disclosure to partners [23, 24], which in turn is associated with disclosure to other loved ones [25], it is therefore possible that early ART initiation may accelerate disclosure and possibly social support [18]. However, because of the very limited time available before initiating treatment, it may also put greater pressure on PLHIV to promptly disclose their seropositivity, something which could possibly lead to stigma, conflict and domestic violence [3]. In addition, early ART initiation in PLHIV with high CD4 counts might enable them to remain asymptomatic, reducing their perceived need to disclose their HIV infection [26], especially in those at risk of experiencing stigma, conflict or domestic violence after disclosure. Evidence for these possible effects of early ART on psychosocial outcomes is still uncertain and they are under-documented [27].

Accordingly, this study aimed to explore the effects of early ART initiation on two critical psychosocial outcomes in PLHIV linked to care in a UTT setting with high HIV prevalence. More specifically, it investigated the effect of early ART initiation on HIV disclosure and on social support among asymptomatic PLHIV with CD4 counts > 500 cells/mm3 who were linked to HIV care in a trial clinic after home-based HIV testing as part of the UTT ANRS 12,249 TasP trial.

Materials and Methods

TasP Trial Design

ANRS 12,249 TasP is a phase 4, open-label, cluster-randomized trial conducted between March 2012 and June 2016 in communities of the Hlabisa subdistrict in rural KwaZulu-Natal, in South Africa, where adult HIV prevalence was estimated at approximately 30% [28]. The Hlabisa sub-district covers approximately 1400 km2 [29] and had a population of 71,925 as of 2011 [30]. The main objective of the trial was to investigate whether universal HIV testing of all the adult population, followed by referral to dedicated trial clinics for immediate ART initiation (irrespective of immunulogical status or clinical stage) of all those identified HIV-positive, would reduce HIV incidence in the area. The trial was implemented in 22 geographic clusters (11 control and 11 intervention clusters, randomly allocated), each comprising approximately 1000 adult residents.

In all clusters, home-based rapid HIV testing and counselling were offered every six months to all members of eligible households (i.e., residents aged ≥ 16 years). People identified HIV-positive (i.e., newly diagnosed or reporting a prior HIV-positive test result) were referred (or newly referred for those with a prior HIV-positive test result but not currently linked to HIV care) to the dedicated trial clinic for their cluster, usually located less than 5 km or a 45-min walk from their home.

The trial clinics in the intervention clusters offered ART immediately to all HIV-positive participants, irrespective of CD4 cell count and clinical stage. Instead, in the control cluster clinics, HIV-positive participants were offered ART according to the eligibility criteria set out in the 2013 South African guidelines: (i) CD4 cell count ≤ 350 cells/mm3; (ii) pregnancy; (iii) WHO stage 3 or 4 [31]. On 1 January 2015, these criteria were revised to include CD4 cell count ≤ 500 cells/mm3, hepatitis B coinfection and having an HIV-negative partner [32]. In all the trial clinics, participants on ART (for both the control and intervention arms) had monthly clinical follow-up visits, whereas pre-ART non-eligible participants in the control clusters were provided quarterly clinical follow-up. HIV care (including ART) was also provided by government (i.e., not trial-specific) clinics located in the trial area according to national guidelines. At their request, participants could transfer out from trial clinics to a government clinic, inside or outside the trial area.

Clinical data were collected by care providers at baseline (i.e., first trial clinic visit) and then at each follow-up visit using case report forms. In addition, socioeconomic and psychosocial information on HIV disclosure, social support, quality of life and relationship status (having a regular partner, relationship duration, break-ups) was obtained from face-to-face questionnaires administered to participants during their baseline clinic visit and every 6 months thereafter. Further details on the trial protocol are available elsewhere [27, 33].

The Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (BFC 104/11) and the South African Medicines Control Council approved the trial. All participants provided written informed consent.

Study Population

For the present study, we first selected participants meeting the following criteria at their baseline clinic visit: not ART-treated, WHO stage 1 or 2, CD4 count > 500 cells/mm3, and not pregnant. We chose a fixed CD4 threshold (> 500 cells/mm3) irrespective of the date of the baseline clinic visit, in order to include participants with similar characteristics. Accordingly, no participant was eligible for ART initiation according to South Africa’s 2013 and 2015 national guidelines. In the intervention arm, all participants were invited to immediately initiate ART: those who accepted therefore benefitted from early ART. Conversely, in the control arm, ART initiation was offered later in the follow-up, if and when a participant became eligible according to South Africa’s 2013 or 2015 guidelines: those who initiated treatment therefore benefitted from delayed ART. Then, for each analysis for the study’s two outcomes (HIV disclosure and social support), from the selected trial participants, we excluded those having fewer than two available measures for the study outcome during the 24-month follow-up period. This choice was justified by the fact that we aimed to assess the effect of early ART initiation on the evolution of psychosocial outcomes. Accordingly, two study populations were obtained, one for the HIV disclosure outcome, and one for the social support outcome.

Study Outcomes

The two study outcomes were HIV disclosure and social support scores. They were assessed using two questions asked at the baseline clinic visit and every 6 months thereafter in psychosocial questionnaires. The two questions were: “Have you disclosed to anyone that you are HIV-positive?” and “Does anyone provide you with social support to help you cope with your HIV infection?”. The HIV disclosure score (range: 0–5) was computed by attributing one point when HIV status was disclosed to each one of the following categories: (i) regular partner; (ii) family (male relatives, female relatives, children); (iii) friends; (iv) neighbors; (v) other people (employer, traditional healer, educational institution, anyone else). Similarly, the social support score (range: 0–4) was computed by attributing one point when the participant reported receiving social support from each one of the following categories: (i) regular partner; (ii) household members (other than the regular partner, if any); (iii) other family members; (iv) friends and neighbors. Scores were expected to increase over follow-up but to taper off as they reached their highest values.

Explanatory Variables

We assessed the effect of three key variables on psychosocial outcomes: (i) the trial arm (intervention versus control); (ii) time since the baseline clinic visit (in years), (iii) a time-varying variable entitled ‘having initiated ART’, taking the value 0 as long as the participant had not started ART in a trial clinic, and 1 from the moment (i.e., the follow-up visit) when the participant initiated ART. This variable took into account the exact timing of ART initiation, as a minority of patients did not initiate ART immediately when offered for a variety of reasons, both in the intervention and control arms.

Other explanatory variables included the following clinical, socioeconomic and psychosocial data, assessed at the baseline clinic visit and used as fixed variables in the analysis: sex, age, educational level, employment status, newly HIV diagnosed at referral (i.e., not reporting any prior HIV-positive diagnosis during the home-based testing, not registered as a HIV patient in a government clinic, and not currently or previously linked to HIV care in a government clinic), time to linkage to a trial clinic after referral (< 1 month, 1 to 6 months, > 6 months), and CD4 cell count. In addition, we used another time-varying variable entitled ‘having a regular partner’, to take into account potential changes in relationships over the follow-up period. We also used HIV prevalence in the geographical cluster of residence (< 30% or ≥ 30%) to account for potential effects related to the high prevalence setting.

Statistical Analysis

The two study populations’ baseline characteristics were described using numbers (percentages) for categorical variables and the median [interquartile range, IQR] for continuous variables. They were then compared between the two trial arms using the Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Using the same tests, we also compared the characteristics of the two study populations with those of the participants excluded because they had fewer than two measures for the corresponding study outcome.

All available values of the two outcomes, measured at baseline and every six months thereafter during the 24-month follow-up period, were included in the analyses. To describe the evolution of the outcomes over follow-up, we compared the medians of each of the two outcome scores between the two trial arms in cross-sectional analyses (i.e. at each 6-month time point during the follow-up period) using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Finally, we performed a longitudinal analysis using Poisson mixed-effects models which took into account the correlation between repeated measures, in order to estimate the effect of early ART on HIV disclosure and social support, after adjustment for other explanatory variables. To do this, we built four different models for each outcome: (i) in model 1, we introduced the two variables ‘time since baseline clinic visit’ and ‘trial arm’ to investigate, respectively, the evolution of outcomes over time and whether the intervention arm was associated with higher outcome scores; (ii) in model 2, we added an interaction between the variables ‘trial arm’ and ‘time since baseline’ to test whether the outcome scores increased faster in the intervention arm than in the control arm; (iii) in model 3, we introduced the variable ‘having initiated ART’ (in addition to the ‘trial arm’ and ‘time since baseline clinic visit’) to assess the effect of treatment initiation on the outcomes; (iv) in model 4, we added an interaction between the ‘trial arm’ and ‘having initiated ART’ variables to investigate the effect of treatment initiation according to the trial arm (early ART in the intervention arm versus delayed ART in the control arm). Each model was also adjusted for any explanatory variables significantly associated with the two outcomes.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software (version 14.2, StataCorp, College Station, Texas 77845 USA).

Results

Profiles of Two Study Populations

Among all the HIV-positive participants referred to the trial clinics over the trial period, 3014 visited a trial clinic at least once (Fig. 1). Of the latter, 1592 (52%) were not on ART at their baseline clinic visit, including 495 (271 and 224 in the control and intervention arms, respectively) who met the present study’s criteria (i.e., CD4 counts > 500 cells/mm3, WHO stage 1 or 2, and not pregnant). Of these pre-selected participants, we excluded 23 as their psychosocial questionnaires at baseline clinic visit were either unavailable or incomplete, leaving 472 potential participants. For the analysis on HIV disclosure, 290 of this group were secondarily excluded as they did not have two available measures for the HIV disclosure score. For the social support analysis, 320 of the 472 were secondarily excluded as they did not have two measures for the social support score. The two study populations therefore included 182 trial participants in the HIV disclosure analysis and 152 in the social support analysis. All those in the latter analysis were also included in the HIV disclosure analysis.

Comparison of the two study populations’ characteristics with those of trial participants who were excluded because they did not have two available measures for the study outcomes, suggested they had similar socioeconomic profiles (Appendices 1 and 2). However, a higher proportion of excluded participants were newly HIV diagnosed (19% versus 8%, p = 0.001 for the study population on HIV disclosure; 18% versus 9%, p = 0.018 for the study population on social support) and had only been linked to care more than six months after referral (33% versus 13%, p < 0.001 for the study population on HIV disclosure; 31% versus 13%, p < 0.001 for the study population on social support), while a lower proportion had previously received HIV care in government clinics (35% versus 52%, p = 0.001 for the study population on HIV disclosure; 39% versus 49%, p = 0.048 for the study population on social support). HIV disclosure and social support scores were not significantly different at baseline between the two study populations and excluded participants.

Characteristics of the 182 trial participants in the HIV disclosure analysis are presented in Table 1, overall and by arm. Most were women (84%), and median age was 32 [interquartile range (IQR): 25–48] years. At baseline, most (79%) reported having a regular partner, and 82% resided in a geographical cluster where HIV prevalence was > 30%. Overall, socioeconomic status was low, with 80% of participants being unemployed and almost half (46%) having primary school education or less. Approximately half (52%) were currently receiving or had already received HIV care in government clinics, and only 8% were newly HIV diagnosed. Almost two-thirds (61%) of the participants were linked to HIV care in a trial clinic within one month of referral. No significant difference was observed at baseline between both trial arms, except for the proportion of participants residing in a geographical cluster where HIV prevalence was ≥ 30% (90% in the intervention arm versus 75% in the control arm, p = 0.010). Median [IQR] time since baseline visit in a trial clinic was 13.2 [7.0–18.5] months. The proportions of participants having initiated ART at various time points over follow-up were as follows: one month after the baseline clinic visit, 8% had initiated ART in the control arm versus 48% in the intervention arm; these figures were 15% versus 92% after 3 months, 22% versus 97% after 6 months, and 29% versus 98% after 12 months, respectively.

Characteristics of the 152 study participants included in the social support analysis were similar to those for the HIV disclosure analysis (Appendix 3).

Evolution of Study Outcomes (HIV Disclosure and Social Support) Over Time

At baseline, the median [IQR] HIV disclosure score in the control and intervention arms was 1 [1–2] and 2 [1–2] (p = 0.72), respectively, while the median social support score was 2 [1–3] and 1 [1–2] (p = 0.12), respectively (Fig. 2). Both outcomes improved over time: 24 months after baseline, the median [IQR] HIV disclosure score was 4 [3–4] and 4 [3–5], respectively, while the median [IQR] social support score was 2 [1–3] and 3 [2–4] (p = 0.47), respectively (p = 0.25).

In addition, Fig. 3, which illustrates the distribution of both outcome scores (according to visit and trial arm), shows that the proportions of participants with an HIV disclosure score ≥ 3 increased in both arms over follow-up and were systematically higher in the intervention arm at all time points (i.e., M0 to M24). The largest differences between trial arms were observed 6 and 12 months after baseline, while differences tended to decrease after 18 months of follow-up. The proportions of participants with a social support score ≥ 3 also increased in both arms over follow-up but tended to increase faster in the intervention arm. More specifically, although a slightly higher proportion of participants had a score ≥ 3 in the control arm than in the intervention arm between baseline and 12 months, the proportions of participants with a score ≥ 3 were similar in both arms at 18 months, and after 24 months, they were slightly higher in the intervention arm.

The Effects of Time Since Baseline, Trial Arm and Having Initiated ART on Both Study Outcomes

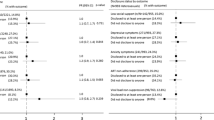

Results of the Poisson mixed effects models are presented in Table 2. Model 1 indicates a significant increase over time for both HIV disclosure and social support scores (adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR), 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.46 [1.35; 1.58], p < 0.001, and 1.33 [1.21; 1.46], p < 0.001, for each year of follow-up, respectively). In addition, model 1 shows that participants in the intervention arm disclosed to more categories of people than participants in the control arm (adjusted IRR [95% CI]: 1.26 [1.12; 1.41], p < 0.001). No difference was observed between arms for the social support score (1.03 [0.90; 1.17], p = 0.690). In model 2, the evolution over time of the HIV disclosure score was similar in both trial arms (1.02 [0.87; 1.19] for the interaction term between time since baseline and arm, p = 0.839). Conversely, a faster increase over time was observed for the social support score in the intervention arm (1.22 [1.02; 1.46] for the interaction term between time since baseline (in years) and arm, p = 0.032). In model 3, having initiated ART was associated with higher scores (1.50 [1.28; 1.75], p < 0.001, for HIV disclosure, and 1.34 [1.12; 1.61], p = 0.002, for social support). The principal effect of the intervention arm on the HIV disclosure score was no longer significant (1.05 [0.92; 1.20], p = 0.467) after adjustment for ART initiation. Model 4 showed that having initiated ART had a similar effect on the HIV disclosure score in both arms (1.15 [0.89; 1.48] for the interaction term between ART initiation and trial arm, p = 0.288). However, it had a stronger effect on the social support score in the intervention arm (1.50 [1.12; 2.01] for the interaction term between ART initiation and arm, p = 0.006).

Discussion

Our study highlighted two key findings. First, HIV disclosure and social support increased over time in both trial arms, independently of ART initiation. This may be explained by the fact that PLHIV are willing to disclose to more people over time as they come to accept their status and overcome feelings of shame [34]. Wider disclosure translates into more opportunities to receive HIV-related social support, and so the latter increases over time. Second, early ART initiation had no detrimental effect on the two study outcomes. On the contrary, it was associated with accelerated HIV disclosure and increased social support. More specifically, HIV disclosure was significantly higher in the intervention arm and was strongly correlated with ART initiation, as demonstrated by the significant effect of the ‘having initiated ART’ variable. In addition, when controlling for the latter, the effect of the trial arm variable was no longer significant, suggesting that early ART initiation offered in the intervention arm did not affect disclosure per se, but modified its timing: the sooner ART was initiated, the faster HIV disclosure occurred. With regard to social support, we observed that it increased significantly faster over time in the intervention arm. This may be explained by a ‘catch-up’ phenomenon, as the level of social support reported by participants tended to be lower at baseline in the intervention arm than in the control arm. However, given the relatively short follow-up period (median time since baseline was approximately 1 year), we were unable to observe whether social support would continue to increase in the intervention arm while remaining stable in the control arm. In addition, PLHIV who initiated ART benefited from greater social support, but only in the intervention arm, as indicated by the interaction term between ‘having initiated ART’ and trial arm, which was significantly associated with social support, while the main effect of ‘having initiated ART’ was no longer significant. This suggests that in a UTT setting, early ART initiation could result in greater social support than delayed ART.

The beneficial indirect (i.e., non-clinical) effects of ART initiation on psychosocial outcomes observed in our study are consistent with the literature [23, 35, 36]. As suggested by previous research, there are several possible reasons to explain why ART initiation encourages PLHIV to disclose their HIV-positive status, such as the desire to be open about taking daily medication or going to the clinic [37, 38] or a greater need for adherence support [23]. Counselling alongside ART initiation may be another reason for increased disclosure after ART initiation. Furthermore, information about the role of ART in maintaining good health and eliminating transmission risk may encourage PLHIV to disclose their status to their partner, which is a first step towards wider disclosure. Finally, reassurance provided by caregivers during counselling sessions alongside ART initiation could also reduce internalized stigma and fear of negative disclosure-related reactions, making patients more comfortable about disclosing their status with their partners. Our findings therefore suggest that delayed treatment initiation in turn delays the possibility of indirect beneficial effects of ART initiation on HIV disclosure.

According to the literature, the positive effect of ART initiation on social support may be partly due to the observed increase in disclosure following ART initiation, the former being at least partially dependent on the latter. Furthermore, the numerous constraints associated with lifelong ART treatment (e.g. transportation for check-ups, treatment reminders, etc.) provide PLHIV’s family members the opportunity to offer greater material, financial and moral support to their loved one once he/she has initiated treatment [20, 38]. In our study, the indirect beneficial effect of ART initiation on social support was observed only in the intervention arm. In Western settings, previous research suggested that HIV disease progression had negative effects on social networks and support, possibly because of changes in affect and cognition, or psychiatric disorders inducing social withdrawal or social selectivity [39, 40]. Although all the PLHIV in our study had high CD4 counts at baseline, our results may suggest that family members and friends may be more likely to provide social support to PLHIV who initiate ART early than when treatment is delayed. This may be explained by the more positive perception of early ART initiation in communities strongly affected by HIV [41].

Our findings showing the psychosocial benefits of early ART initiation are consistent with the results of another early ART initiation clinical trial in West Africa which highlighted that early ART had no adverse social consequences on either conjugal relationships or HIV-related discrimination [42]. Similarly, in another study conducted within the ANRS 12,249 TasP trial, the authors found no increase in sexual behavior risks [43]. The beneficial effects of early ART on the two study outcomes we explored (HIV disclosure and social support) may also have positive synergies with other outcomes which are key factors for the treatment success. This is especially the case with ART adherence, as suggested by another study conducted using data from the ANRS 12,234 TasP trial, which showed that higher CD4 counts at ART initiation were not associated with sub-optimal ART adherence in the first 12 months [44]. Besides individual benefits, earlier HIV disclosure and greater social support may also have potential benefits at the community level. Disclosure to partners could help to reduce HIV transmission through decreased risky sexual behaviors, increased condom negotiation and use [45,46,47,48,49], higher partner HIV testing [24], and better ART adherence [50]. As part of a UTT strategy, the potential benefits of HIV disclosure following early ART initiation may also contribute to better control HIV epidemics nationwide. Moreover, in the context of South Africa, where HIV is highly endemic in the general population, and not limited to excluded minorities, we found that social support increased as HIV disclosure increased. This suggests a positive social impact of HIV disclosure, which is consistent with previously published studies in South Africa describing greater social support from relatives following HIV disclosure [49, 51, 52].

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Our study brings added evidence for the positive effects of earlier ART initiation on two critical psychosocial outcomes in a UTT setting: HIV disclosure and social support. To provide a better understanding of these effects, we disentangled the respective effects of time, trial arm and ART initiation. The two-arm cluster-randomized design of the ANRS 12249 TasP allowed us to examine the causal effect of early ART on these outcomes.

Our study has limitations. Firstly, we excluded a large number of trial participants because they had fewer than two measures for each of the study outcomes (i.e., 290/495 and 320/495 for the HIV disclosure and social support analyses, respectively). Most of these excluded participants were included in the last year of the trial (in 2016) which explains why they did not have two measures for each outcome. Their characteristics were overall similar to those of the two study populations, except they were more likely to be newly HIV diagnosed and to have experienced a longer delay before linkage to care. Furthermore, their HIV disclosure and psychosocial support scores were not significantly different from those of the two study populations at baseline. Although we cannot completely exclude the risk of selection bias, these data suggest that if the trial’s follow-up period had been longer—enabling us to include those individuals—our present results would probably have been similar.

Secondly, the methodology used to measure disclosure and social support had several drawbacks. For a start, the maximum possible scores for disclosure and social support were automatically lower for participants with no regular partner, as one point was awarded for those disclosing to their regular partners. As the relatively small size of both study populations prevented us from performing a stratified analysis to distinguish those with from those without a regular partner, we addressed this limitation by adjusting all models for the variable ‘having a regular partner’ which was assessed at each time point. Moreover, the HIV disclosure score did not measure involuntary HIV disclosure by a third person, despite the fact that this is associated with more frequent adverse social consequences [53]. However, the parallel increase in both HIV disclosure and social support scores following ART initiation suggested that negative social implications of HIV disclosure were limited. In addition, we did not ask PLHIV why they disclosed their HIV status. Neither did we ask them in what specific ways they received social support to help them cope with the disease. Such information might have helped us to understand in greater detail the mechanisms underlying the effects of early ART initiation observed in this study.

Thirdly, given the limited study population size, we were not able to conduct a stratified analysis according to gender. Such an analysis would have been valuable, given that current evidence—despite being mixed—tends to suggest that patterns of HIV disclosure and seeking social support may be gender dependent (45).

Conclusion

The implementation of a universal test and treat strategy raises questions about the psychosocial implications of early ART initiation. Our findings, together with those from other recent studies, are reassuring as they suggest that early ART does not have detrimental effects on HIV disclosure or on social support. On the contrary, it tends to improve these two key outcomes. They also suggest that more time may be needed to see the beneficial effects of early ART on social support than on disclosure. This is to be expected, since social support is at least partially dependent on disclosure. Our findings should further encourage countries to implement UTT strategies.

References

Moir S, Buckner CM, Ho J, Wang W, Chen J, Waldner AJ, et al. B cells in early and chronic HIV infection: evidence for preservation of immune function associated with early initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Blood. 2010;116(25):5571–9.

Schuetz A, Deleage C, Sereti I, Rerknimitr R, Phanuphak N, Phuang-Ngern Y, et al. Initiation of ART during early acute HIV infection preserves mucosal Th17 function and reverses HIV-related immune activation. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10(12):e1004543.

Ford N, Migone C, Calmy A, Kerschberger B, Kanters S, Nsanzimana S, et al. Benefits and risks of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Lond Engl. 2018;32(1):17.

Donnell D, Baeten JM, Kiarie J, Thomas KK, Stevens W, Cohen CR, et al. Heterosexual HIV-1 transmission after initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a prospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2092–8.

Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505.

Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach—2010 revision [Internet]. [cité 5 mars 2019]. Disponible sur: https://apps-who-int.gate2.inist.fr/iris/handle/10665/44379

WHO | Consolidated ARV guidelines 2013 [Internet]. WHO. [cité 5 mars 2019]. Disponible sur: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/art/statartadolescents_rationale/en/

World Health Organization, World Health Organization, Department of HIV/AIDS. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. [Internet]. 2015 [cité 8 mars 2019]. Disponible sur: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK327115/

Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell M-L. High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Sci. 2013;339(6122):966–71.

Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):48–57.

Phillips AN, Cambiano V, Miners A, Lampe FC, Rodger A, Nakagawa F, et al. Potential impact on HIV incidence of higher HIV testing rates and earlier antiretroviral therapy initiation in MSM. AIDS Lond Engl. 2015;29(14):1855.

Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Larmarange J, Balestre E, Thiebaut R, Tanser F, et al. Universal test and treat and the HIV epidemic in rural South Africa: a phase 4, open-label, community cluster randomised trial. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(3):e116–25.

Hayes R, Ayles H, Beyers N, Sabapathy K, Floyd S, Shanaube K, et al. HPTN 071 (PopART): rationale and design of a cluster-randomised trial of the population impact of an HIV combination prevention intervention including universal testing and treatment–a study protocol for a cluster randomised trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):57.

Sustainable East Africa Research in Community Health—Tabular View—ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. [cité 5 mars 2019]. Disponible sur: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT01864603

Perriat D, Balzer L, Hayes R, Lockman S, Walsh F, Ayles H, et al. Comparative assessment of five trials of universal HIV testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(1):e25048.

Abdool-Karim SS. HIV-1 epidemic control—insights from test-and-treat trials. Mass Medical Soc. 2019;381:286–8.

Makhema J, Wirth KE, Pretorius Holme M, Gaolathe T, Mmalane M, Kadima E, et al. Universal testing, expanded treatment, and incidence of HIV infection in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(3):230–42.

Bekele T, Rourke SB, Tucker R, Greene S, Sobota M, Koornstra J, et al. Direct and indirect effects of perceived social support on health-related quality of life in persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2013;25(3):337–46.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41.

Khamarko K, Myers JJ, Organization WH. The Influence of social support on the lives of HIV-infected individuals in low-and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

Greeff M, Uys LR, Wantland D, Makoae L, Chirwa M, Dlamini P, et al. Perceived HIV stigma and life satisfaction among persons living with HIV infection in five African countries: a longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(4):475–86.

Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1266–75.

Haberlen SA, Nakigozi G, Gray RH, Brahmbhatt H, Ssekasanvu J, Serwadda D, et al. Antiretroviral therapy availability and HIV disclosure to spouse in Rakai, Uganda: a longitudinal population-based study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(2):241.

King R, Katuntu D, Lifshay J, Packel L, Batamwita R, Nakayiwa S, et al. Processes and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure to sexual partners among people living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav Mars. 2008;12(2):232–43.

Suzan-Monti M, Kouanfack C, Boyer S, Blanche J, Bonono R-C, Delaporte E, et al. Impact of HIV comprehensive care and treatment on serostatus disclosure among Cameroonian patients in rural district hospitals. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(1):e55225.

Petrak JA, Doyle A-M, Smith A, Skinner C, Hedge B. Factors associated with self-disclosure of HIV serostatus to significant others. Br J Health Psychol. 2001;6(1):69–79.

Orne-Gliemann J, Larmarange J, Boyer S, Iwuji C, McGrath N, Bärnighausen T, et al. Addressing social issues in a universal HIV test and treat intervention trial (ANRS 12249 TasP) in South Africa: methods for appraisal. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):209.

Zaidi J, Grapsa E, Tanser F, Newell M-L, Bärnighausen T. Dramatic increases in HIV prevalence after scale-up of antiretroviral treatment: a longitudinal population-based HIV surveillance study in rural kwazulu-natal. AIDS Lond Engl. 2013;27(14):2301.

Hlabisa case book in HIV & TB medicine. Dr Tom Heller; 152 p.

Hlabisa Local Municipality—Demographic. [cité 28 févr 2019]. Disponible sur: https://municipalities.co.za/demographic/1092/hlabisa-local-municipality

National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. The South African antiretroviral treatment guidelines. Pretoria: Department of Health, Republic of South Africa; 2013.

National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa. National consolidated guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. Pretoria: Department of Health, Republic of South Africa; 2015.

Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Tanser F, Boyer S, Lessells RJ, Lert F, et al. Evaluation of the impact of immediate versus WHO recommendations-guided antiretroviral therapy initiation on HIV incidence: the ANRS 12249 TasP (Treatment as Prevention) trial in Hlabisa sub-district, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14(1):230.

Gultie T, Genet M, Sebsibie G. Disclosure of HIV-positive status to sexual partner and associated factors among ART users in Mekelle hospital. HIVAIDS Auckl N Z. 2015;7:209.

Kouanda S, Yaméogo WME, Berthé A, Bila B, Yaya FB, Somda A, et al. Partage de l’information sur le statut sérologique VIH positif: facteurs associés et conséquences pour les personnes vivant avec le VIH/sida au Burkina Faso. Rev DÉpidémiologie Santé Publique. 2012;60(3):221–8.

Fitzgerald M, Collumbien M, Hosegood V. “No one can ask me ‘Why do you take that stuff?’”: men’s experiences of antiretroviral treatment in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010;22(3):355–60.

Pouvoir partager / Pouvoirs Partagés | Dévoilement. [cité 16 janv 2019]. Disponible sur: http://pouvoirpartager.uqam.ca/devoilement.html

Sow K. Partager l’information sur son statut sérologique VIH dans un contexte de polygamie au Sénégal: HIV disclosure in polygamous settings in Senegal. SAHARA-J J Soc Asp HIVAIDS. 2013;10(sup1):S28–36.

Miller GE, Cole SW. Social relationships and the progression of human immunodeficiency virus infection: a review of evidence and possible underlying mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 1998;20(3):181–9.

Kaplan RM, Patterson TL, Kerner D, Grant I. Social support: cause or consequence of poor health outcomes in men with HIV infection? In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR, editors. Sourcebook of social support and personality. New York: Plenum Press; 1997. p. 279–301.

Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Larmarange J, Okesola N, Tanser F, Thiebaut R, et al. Uptake of home-based HIV testing, linkage to care, and community attitudes about ART in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: descriptive results from the first phase of the ANRS 12249 TasP cluster-randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002107.

Jean K, Niangoran S, Danel C, Moh R, Kouamé GM, Badjé A, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy initiation in west Africa has no adverse social consequences: a 24-month prospective study. AIDS Lond Engl. 2016;30(10):1677–82.

Rolland M, McGrath N, Tiendrebeogo T, Larmarange J, Pillay D, Dabis F, et al. No effect of test and treat on sexual behaviours at population level in rural South Africa. AIDS. 2019;33(4):709–22.

Iwuji C, McGrath N, Calmy A, Dabis F, Pillay D, Newell M-L, et al. Universal test and treat is not associated with sub-optimal antiretroviral therapy adherence in rural South Africa: the ANRS 12249 TasP trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(6):e25112.

Obermeyer CM, Baijal P, Pegurri E. Facilitating HIV disclosure across diverse settings: a review. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(6):1011–23.

Loubiere S, Peretti-Watel P, Boyer S, Blanche J, Abega S-C, Spire B. HIV disclosure and unsafe sex among HIV-infected women in Cameroon: results from the ANRS-EVAL study. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(6):885–91.

Olley BO, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Self-disclosure of HIV serostatus in recently diagnosed patients with HIV in South Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2004;8:71–6.

Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Strebel A, Cloete A, Henda N, Mqeketo A. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners and sexual risk behaviours among HIV-positive men and women, Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83(1):29–34.

Wong LH, Van Rooyen H, Modiba P, Richter L, Gray G, McIntyre JA, et al. Test and tell: correlates and consequences of testing and disclosure of HIV status in South Africa (HPTN 043 Project Accept). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50(2):215.

Hodgson I, Plummer ML, Konopka SN, Colvin CJ, Jonas E, Albertini J, et al. A systematic review of individual and contextual factors affecting ART initiation, adherence, and retention for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e111421.

Skogmar S, Shakely D, Lans M, Danell J, Andersson R, Tshandu N, et al. Effect of antiretroviral treatment and counselling on disclosure of HIV-serostatus in Johannesburg. South Africa AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):725–30.

Skhosana NL, Struthers H, Gray GE, McIntyre JA. HIV disclosure and other factors that impact on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: the case of Soweto, South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res. 2006;5(1):17–26.

Lyimo RA, Stutterheim SE, Hospers HJ, de Glee T, van der Ven A, de Bruin M. Stigma, disclosure, coping, and medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS in Northern Tanzania. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2014;28(2):98–105.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks to the PLHIV and workers who participated into the TasP trial. This study was funded by the ANRS (France Recherche Nord & Sud Sida-HIV Hépatites; ANRS 12324). We also thank Jude Sweeney for revising and editing the English version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Baseline Characteristics Regarding HIV Disclosure for the Study Population on (n = 182) and for Participants Excluded Because Only One Measure of this Outcome was Available for the Whole Study Period (n = 290), ANRS 12,249 TasP trial

Covariates | Study population (n = 182) | Excluded participants (n = 290) | Total (n = 472) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics | ||||

Female gender, n (%) | 152(84%) | 240 (83%) | 392 (83%) | 0.831 |

Age (in years), median [IQR]* | 32 [25–48] | 30 [24–44] | 31 [25–45] | 0.155 |

Having a regular partner, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 144 (79%) | 235 (81%) | 379 (80%) | 0.611 |

HIV prevalence in the geographical cluster of residence, n (%) | ||||

≥ 30% | 150 (82%) | 211 (73%) | 361 (77%) | 0.016 |

Educational level#, n (%) | 0.162 | |||

Primary or less | 84 (46%) | 117 (41%) | 201 (43%) | |

Some secondary | 58 (32%) | 116 (41%) | 174 (37%) | |

At least completed secondary | 40 (22%) | 53 (19%) | 93 (20%) | |

Employment status§, n (%) | 0.788 | |||

Employed | 21 (12%) | 38 (13%) | 59 (13%) | |

Student | 14 (8%) | 19 (7%) | 33 (7%) | |

Inactive | 146 (81%) | 224 (80%) | 370 (80%) | |

Clinical characteristics | ||||

Having received HIV care in government clinics (currently or previously), n (%) | ||||

Yes | 94 (52%) | 105 (35%) | 199 (42%) | 0.001 |

Newly diagnosed, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 14 (8%) | 56 (19%) | 70 (15%) | 0.001 |

CD4 cell count/mm3, median [IQR] | 660 [568–816] | 665 [569–801] | 662 [569–807] | 0.566 |

Time to linkage to a trial clinic after referral, n (%) | 0 | |||

0–1 month | 111 (61%) | 143 (49%) | 254 (54%) | |

1–6 months | 47 (26%) | 51 (18%) | 98 (21%) | |

More than 6 months | 24 (13%) | 96 (33%) | 120 (25%) | |

HIV disclosure score, median [IQR] | 0.915 |

Appendix 2: Baseline Characteristics Regarding Social Support for the Study Population (n = 152) and of for Participants Excluded Because Only One Measure for This Outcome was Available for the Whole Study Period (n = 320), ANRS 12,249 TasP trial

Study population (n = 152) | Excluded participants (n = 320) | Total (n = 472) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics | ||||

Female gender, n (%) | 128 (84%) | 264 (83%) | 392 (83%) | 0.643 |

Age (in years), median [IQR]* | 32 [25–48] | 30 [24–44] | 31 [25–45] | 0.34 |

Having a regular partner, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 120 (79%) | 259 (81%) | 379 (80%) | 0.612 |

HIV prevalence in the geographical cluster of residence, n (%) | ||||

≥ 30% | 124 (82%) | 237 (74%) | 362 (77%) | 0.072 |

Educational level#, n (%) | 0.211 | |||

Primary or less | 70 (46%) | 131 (41%) | 201 (43%) | |

Some secondary | 48 (32%) | 126 (40%) | 174 (37%) | |

At least completed secondary | 34 (22%) | 59 (19%) | 93 (20%) | |

Employment status$, n (%) | 0.343 | |||

Employed | 15 (10%) | 44 (14%) | 59 (13%) | |

Student | 13 (9%) | 20 (6%) | 33 (7%) | |

Inactive | 123 (81%) | 247 (80%) | 371 (80%) | |

Clinical characteristics | ||||

Having received HIV care in government clinics (currently or previously), n (%) | ||||

Yes | 74 (49%) | 125 (39%) | 199 (42%) | 0.048 |

Newly diagnosed at referral, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 14 (9%) | 56 (18%) | 70 (15%) | 0.018 |

CD4 cell count/mm3, median [IQR] | 661 [572–824] | 663 [569–796] | 662 [569–807] | 0.938 |

Time to linkage to a trial clinic after referral, n (%) | 0 | |||

0–1 month | 94 (62%) | 160 (50%) | 254 (54%) | |

1–6 months | 38 (25%) | 60 (19%) | 98 (21%) | |

More than 6 months | 20 (13%) | 100 (31%) | 120 (25%) | |

Social support score, median [IQR] | 1 [1–2.5] | 1 [0–2] | 1 [1–2] | 0.265 |

Appendix 3: Characteristics of the Study Population Regarding the Outcome Social Support (n = 152), ANRS 12,249 TasP trial

Control (n = 75) | Intervention (n = 77) | Total (n = 152) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sociodemographic and economic characteristics at baseline (i.e. first clinic visit) | ||||

Female gender, n (%) | 63 (84%) | 65 (84%) | 128 (84%) | 0.944 |

Age (in years), median [IQR] | 32 [24–48] | 32 [25–47] | 32 [25–48] | 0.535 |

Having a regular partner, n (%) | ||||

Yes | 56 (75%) | 64 (83%) | 120 (79%) | 0.201 |

HIV prevalence in the geographical cluster of residence, n (%) | 0.004 | |||

≥ 30% | 68 (91%) | 56 (73%) | 124 (82%) | |

Educational level, n (%) | 0.556 | |||

Primary or less | 36 (48%) | 34 (44%) | 70 (46%) | |

Some secondary | 25 (33%) | 23 (30%) | 48 (32%) | |

At least completed secondary | 14 (19%) | 20 (26%) | 34 (22%) | |

Employment status$, n (%) | 0.379 | |||

Employed | 8 (11%) | 7 (9%) | 15 (10%) | |

Student | 4 (5%) | 9 (12%) | 13 (9%) | |

Inactive | 62 (84%) | 61 (79%) | 123 (81%) | |

Clinical characteristics | ||||

Having received HIV care in government clinics (currently or previously), n (%) | ||||

Yes | 41 (55%) | 33 (43%) | 74 (49%) | 0.145 |

Newly diagnosed at referral, n(%) | 7 (9%) | 7 (9%) | 14 (9%) | 0.959 |

Yes | ||||

CD4 cell count/mm3at baseline, median [IQR] | 687 [581–840] | 655 [551–815] | 661 [572–824] | 0.49 |

Time to linkage to a trial clinic after referral, n (%) | 0.851 | |||

0–1 month | 46 (61%) | 48 (62%) | 94 (62%) | |

1–6 months | 20 (27%) | 18 (23%) | 38 (25%) | |

More than 6 months | 9 (12%) | 11 (14%) | 20 (13%) | |

Time since baseline (in years), median [IQR] | 13.9 [7.3–19.8] | 15.1 [8.3–19.8] | 14.1 [7.8–19.8] | 0.804 |

Followed for at least 6 months, n(%) | 75 (100%) | 77 (100%) | 152 (100%) | |

Followed for at least 12 months, n(%) | 49 (65%) | 50 (65%) | 99 (65%) | 0.959 |

Followed for at least 18 months, n(%) | 27 (36%) | 32 (42%) | 59 (39%) | 0.482 |

Followed for at least 24 months, n(%) | 11 (15%) | 9 (12%) | 20 (13%) | 0.587 |

Having initiated ART in a trial clinic after baseline, n (%) | ||||

At the 6 month-visit | 9 (20%) | 62 (98%) | 71 (66%) | 0 |

At the 12 month-visit | 12 (31%) | 40 (98%) | 52 (65%) | 0 |

At the 18 month-visit | 13 (59%) | 31 (97%) | 44 (81%) | 0.001 |

At the 24 month-visit | 9 (82%) | 9 (100%) | 18 (90%) | 0.479 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fiorentino, M., Nishimwe, M., Protopopescu, C. et al. Early ART Initiation Improves HIV Status Disclosure and Social Support in People Living with HIV, Linked to Care Within a Universal Test and Treat Program in Rural South Africa (ANRS 12249 TasP Trial). AIDS Behav 25, 1306–1322 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03101-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03101-y