Abstract

Background

Long-term outcomes of children with nephrotic syndrome have not been well described in the literature.

Methods

Cross-sectional study data analysis of n = 43 patients with steroid-sensitive (SSNS) and n = 7 patients with steroid-resistant (SRNS) nephrotic syndrome were retrospectively collected; patients were clinically examined at a follow-up visit (FUV), on average 30 years after onset, there was the longest follow-up period to date.

Results

The mean age at FUV was 33.6 years (14.4–50.8 years, n = 41). The mean age of patients with SSNS at onset was 4.7 years (median 3.8 years (1.2–14.5 years), the mean number of relapses was 5.8 (0 to 29 relapses). Seven patients (16.3%) had no relapses. Eleven patients were “frequent relapsers” (25.6%) and four patients still had relapses beyond the age of 18 years. Except of cataracts and arterial hypertension, there were no negative long-term outcomes and only one patient was using immunosuppressant therapy at FUV. 55% of patients suffered from allergies and 47.5% had hypercholesterolemia. Two patients suffered a heart attack in adulthood. A younger age at onset (< 4 years) was a risk factor for frequent relapses. An early relapse (within 6 months after onset) was a risk factor and a low birth weight was not a significant risk factor for a complicated NS course. The mean age of patients with SRNS at onset was 4.6 ± 4.4 years and 27.5 ± 9.9 years at FUV. Three patients received kidney transplantations.

Conclusions

The positive long-term prognosis of SSNS can reduce the concern of parents about the probability of the child developing a chronic renal disease during the clinical course after onset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Nephrotic syndrome (NS) in childhood is characterized by macroproteinuria, hypoalbuminuria, edema, and hyperlipidemia [1, 2].

The annual incidence of idiopathic NS varies in some populations and is currently described to be 2–7/100,000 children [3]. According to our recently published ESPED study, the incidence of NS in Germany is 1.2–1.8 per 100,000 children ≤ 18 years [4].

The etiopathogenesis of primary idiopathic NS, affecting the majority of the patients (90%), is still unclear. The secondary and symptomatic form of NS is mostly due to drugs and toxins or presents itself as a part of a systemic disease [5].

NS is classified into steroid-sensitive (SSNS) and steroid-resistant (SRNS) nephrotic syndrome, depending on the response of national guideline-orientated steroid therapy [1]. SSNS is benign and mostly cured before adulthood, although the disease can represent itself at various timepoints over many years [6, 7].

SRNS has a considerably poorer prognosis than SSNS and often results in chronic kidney disease in the clinical course; 40% of SRNS patients may have chronic kidney disease 10 years after NS onset [8, 9]. The clinical course, complications, and the outcome of pediatric patients with NS in adulthood are not well known or analyzed. Caregivers are often worried about the long-term health outcomes for their children with NS due to the lack of knowledge about the long-term outcomes from NS.

A complicated course is characterized by a high number of relapses, frequent relapses, a high cumulative duration of onset, as well as, a high cumulative steroid dose or alternative immunosuppressant therapy.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the long-term outcome of patients diagnosed with childhood NS during the years 1957–1995 through a prospective follow-up visit (FUV). The FUV included clinical inspection, blood analysis, ultrasonography of the kidneys, and a health survey questionnaire to investigate kidney function, renal growth, cardiovascular disease (e.g. arterial hypertension or lipid metabolic disorders), bone metabolism, height and weight after long steroid therapy, fertility (particularly in males patients who received chlorambucil and cyclophosphamide therapy) or difficulties during pregnancy, and social outcomes of patients 10–45 years after the first NS onset. Furthermore, this retrospective data analysis served to record disease course in childhood, detection of comorbidities, and complication of disease (such as peritonitis, sepsis, nephrotic crisis, or thromboembolic occurrences) and disease course, and relapses in adulthood, as well as, to identify risk factors associated with complications or negative outcomes for patients.

Methods

NS in childhood is defined as a heavy proteinuria ≥ 40 mg/m2/h and hypalbuminuria ≤ 25 g/l [1, 2]. According to the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children (ISKDC) and German Society of Pediatric Nephrology, a remission is defined as a proteinuria < 4 mg/m2/h, albumin detection in a morning urine sample on 3 successive days. A partial remission is defined as serum albumin < 25 g/l with persistent proteinuria < 40 mg/m2/h (approx. 1 g/m2/day) or albumin detection in morning urine samples. Patients with SSNS who have less than two relapses within 6 months after positively responding to steroids are defined as “infrequent relapsers”. Patients with SSNS who have more than two relapses within 6 months or more than four relapses within 12 months after responding to steroid therapy are defined as “frequent relapsers” (Table 1).

Signs of osteoporosis were measured through bone-density measurements (DXA) and biochemical blood and urine samples. Biochemically, predictors for osteoporosis include an elevated bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (AP) in blood, elevated calcium and pyridinoline in urine or a bone-density measurement (BDT). Calcium and deoxypyridinoline were measured in a morning urine sample and recorded as a quotient based on the creatinine (calcium or DPD-creatinine quotient).

This is an analytical, cross-sectional and longitudinal study. All retrospectively and prospectively analyzed data involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-University, Bonn, Germany, and the study was assigned the human study registration number 081/05.

Retrospectively, patient records from patients diagnosed with primary NS and treated at the Department of General Pediatrics, University Children’s Hospital, Bonn, Germany were collected for this study. Inclusion criterion was the onset of primary NS before 31.01.1995 (for a minimal observation period of 10 years). Thereby, all patients with primary NS independently of the response of therapy and histological diagnoses were primarily enrolled in the study. Fifty-nine patients with the above inclusion criteria were treated in the years of 1957–2005 in our pediatric nephrology unit and were identified as being eligible, and efforts were made to contact them all. All patients who participated in the study provided written informed consent. Data extraction and analyses were performed pseudonymously. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

After providing written informed consent, the participants were invited to the children’s hospital for a FUV. Participants filled out a standardized physical examination sheet consisting questions on the clinical course after NS onset in childhood, kidney or other extrarenal diseases, current medical treatments, family, and social life. A physical examination, and urine and blood analyses were conducted, followed by an ultrasonography of the kidneys and the urinary tract, and the renal function was measured by eGFR by Schwartz formula. All results were then shared with the participants and their physicians.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS program 14.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Data are presented as mean and standard deviation or median with range or as absolute values with percentages. Comparisons between two groups were performed with Chi-square test. Exact test according to Fischer and t test for independent samples were completed with the Mann–Whitney U test. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Clinical course

A total of 59 patients were identified as being eligible and efforts were made to contact them all. In 50 of 59 eligible patients (84.5%) (Table 2), data from at least 10 years (range 10–45 years) after onset are available 43 patients with SSNS, 7 patients with SRNS (Fig. 3S). A total number of 34 patients attended the FUV (including clinical inspection, diagnostics, and survey). Further six patients provided their history through a telephone interview or by post. Through cooperation with the attending family doctor or nephrologists or during the FUV, information for seven patients was collected. Three patients were be retrospectively enrolled as data were available through their routine visits to our outpatient clinics. Eight patients were unable to attend the FUV due to a change of residence and one patient died as a result of a stroke.

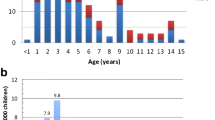

The mean age at onset was 4.7 years (1.2–14.5 years) (Fig. 1). The average age of the entire cohort at FUV was 33.6 years (14.4–50.8 years; n = 41). The mean age at FUV was 36.5 years (14.8–51.3 years, n = 47). Thus, the mean observation period was 29.0 years at FUV (10.6–45.0 years) and 35.4 years (10.6–45.0 years) at survey. The sex ratio was 2.3: 1 (males–females) (Table 3).

Nine subjects (21%, n = 43) had a florid infection of the airways at NS onset, twenty-seven patients (62.8%) had no infections, and no information was available for 7. Twelve patients (27.9%) had only one relapse, and thirty-one subjects (72.1%) had more than two relapses (n = 43).

The interval between NS onset and last relapse (or for patients without relapses, the duration of time since onset) was on average 6.3 years (range 11 days to 19 years). The mean age at the time of the last relapse was 10.9 years ± 5.9 (2–29.4 years) (Fig. 2).

Frequency of relapses, sex, and ethnicity

Males had an average of 6.7 relapses and females 3.8 relapses. The mean duration of initial manifestation (the duration of NS), and mean duration of relapse was 138.2 days for males and 88.9 days for females. Neither males nor females were predisposed for frequent relapses or for complicated courses. Thirty-seven of forty-three subjects with SSNS (86%) had German origins (patients born in Germany) and six (14%) subjects had other ethnic origins.

Young patients at onset and patients with the early relapse

Participants who were less than 4 years of age at NS onset had significantly more relapses (p = 0.042) and a higher cumulative dose of steroids (p = 0.004) (Table 4) than those older than 4 years of age at NS onset.

Participants with early relapses (within 6 months after onset) had significantly more frequent relapses (p = 0.001), a higher cumulative steroid intake (p = 0.001), a longer cumulative duration of onset and relapse (p = 0.007), and a longer duration of disease in years (p = 0.002), and were older at the time of the last relapse (p = 0.001) (Table 5).

Patients with frequent relapses

Eleven of the forty-three patients (25.6%) with SSNS were frequent relapsers (SSNS patients who had more than two relapses within 6 months or more than four relapses within 12 months after response on steroid therapy) and 74.7% had no relapses or were infrequent relapsers (SSNS patients who had less than two relapses within 6 months after positively response on steroids). Frequent relapsers were younger at the initial NS onset and were older at the time of the last relapse, had a longer cumulative duration of disease (p = 0.015), and had a higher number of relapses (p < 0.001) (Table 6). Four of forty-one patients (9.8%; missing information in n = 2) also suffered from relapses in adulthood (Table 7).

Renal morbidity

Kidney biopsies were performed in 12 of 43 patients (27.9%) with SSNS. In ten of these cases (93.3%), minimal change glomerulonephritis, in one patient, a membranous glomerulonephritis, and, in one patient, a focal segmental glomerulonephritis were observed. An ultrasonography of the kidneys (n = 25) showed age-appropriate renal volumes and a normal echogenicity in all patients. One patient had a slightly flared renal pelvis (12 mm on average). Two patients had unilateral duplex kidney conditions and two patients had a solitary cyst.

The renal function was evaluated via the parameters creatinine in serum, eGFR by Schwartz formula (calculated as GFR ml/min × 1.73m2 = k × length [cm]/creatinine in serum; k = 0.55 mg/dl for females > 12 age of years; k = 0.70 mg/dl for males > 12 age of years) cystatin C, beta-2-microglobulin, beta trace protein, and urea in serum in 37 patients (Table 8). One patient had a decreased eGFR (70 ml / min × 1.73 m2) at FUV, a slightly increased serum creatinine (1.22 mg/dl), and an increased phosphate in serum (2.99 mmol/l). This patient was still treated with cyclosporine A and steroids at the FUV. One patient had a significantly high proteinuria at FUV and was subsequently diagnosed with a relapse.

The protein excretion varied from < 50 up to 103 mg/l (n = 33). Two patients (n = 29) had microalbuminuria at the FUV (> 30 mg / l). Beta-2-microglobuline in urine was normal in 29 patients. Alpha-2-macroglobuline, IgG, and alpha-1-microglobuline were normal in all patients. The urine creatinine values varied between 64 and 298 mg/dl with a mean of 162 mg/dl.

Birth weight

The mean birth weight was 3418 g (n = 34). Three patients had a low birth weight (< 2500 g). Children with a birth weight ≤ 3000 g (n = 10) were younger at NS onset and experienced more complications, with a higher number of relapses, a higher cumulative steroids intake, and a prolonged duration of disease and relapses compared to children with a birthweight below 3000 g (n = 24).

Bone metabolism

Anamnestically, 3 of 43 patients who attended the FUV had osteopenia. In one patient with known osteopenia, no laboratory values were available concerning to the bone metabolism and the results of the BDT were not available at the FUV as it was performed by the family physician, who then shared the results with the study center. It is hypothesized that this patient has a steroid-induced osteopenia as a result of a yearlong steroid treatment (recent treatment dose: prednisolone 4 mg/48 h). In another patient with known osteopenia, the Z-score of the BDT of the right heel in the year 2002 was − 1.12, the T-score was − 2.17. The values of the AP, DPD creatinine, and calcium-creatinine quotient in urine were within the normal range. This patient was taking calcium and vitamin D3 at FUV. The cumulative steroid total dose was 884 mg/kg (in comparison, the mean of the steroid dose of all study patients is 753 mg/kg, n = 43). The third patient with osteopenia was 20 years old at FUV and was currently receiving Prednisolone (5 mg/day), ciclosporin A (170 mg/day), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) (1250 mg), and rocaltrol (1 µg/48 h). An X-ray of the left hand in the year 2003 showed osteopenia. The DPD-creatinine quotient was 14 nmol DPD/mmol Crea in Urine (the highest measured value in our study cohort). The AP was 22 µg/l (highest measured value in our cohort).

The bone-specific AP of the overall study participants was increased to values between 15.2 and 22.3 µg/l in 9 patients (36%), but was normal in 25 patients (4.5–14.5 µg/l). Urine calcium levels were between 0.71 and 11.23 mmol/l (n = 32) and the calcium-creatinine ratio in the urine was 0.0047–0.227 mg (n = 31). An increased DPD-creatinine ratio in the urine or an increased AP was not significantly correlated with a high steroid dose or a severe clinical course (number of relapses, duration of onset and of relapse). Radiographic signs of osteoporosis were detected in 8 (18.6%; n = 43) patients.

The mean cumulative steroid dose based on body weight is 1267 mg/kg in patients with elevated bone-specific AP and 597 mg/kg in patients with normal AP (not significant). The first morning urine sample contains an average of 62.6 (18.8–113 nmol/l; n = 30) deoxypyridinoline (DPD). The mean urine DPD-creatinine quotient was 5.5 nmol DPD/mmol Krea (3–14 nmol DPD/mmol Krea; n = 30).

According to the DPD values of the Society for Immune Chemistry and Immunobiology Hamburg, 33% of patients (10/30) had elevated urine DPD/mmol creatinine values. Parathormone (n = 29) was slightly below normal in two patients with 9 and 11 pg/ml (reference range: 12–65 pg/ml). 1.25-Dihydroxyvitamin D (n = 28) was high, ranging from 62.7 up to 75.3 pg/ml in 6 patients (reference range: 18–62 pg/ml). 25-hydroxy vitamin D (n = 29) was reduced to 7.2 and 8.7 ng/ml in 2 patients and was high (48.7 ng/ml) in one patient (reference range: 9.2–45.2 ng/ml).

Cardiovascular system and other comorbidities in childhood

Nineteen of the forty patients (47.5%) had hypercholesterolemia (only one patient was under treatment) at FUV. The concentration of triglycerides in 2 cases (7.4%, mean: 140 mg/dl, range: 37–711, SD: 130 mg/dl; n = 27), the cholesterol in 8 cases (25%;mean: 202 mg/dl, range: 121–325, SD: 44 mg/dl; n = 32), and the LDL cholesterol in 7 cases (25.9%; mean: 130 mg/dl, range: 58–216, SD 40 mg/dl; n = 27) were increased. The HDL/LDL quotient was decreased in 16 patients (59.3%; HDL cholesterol: mean 52 mg/dl, range: 30–111, SD 17 mg/dl; n = 27) and the lipoprotein (a) in serum was increased in ten patients (37%; mean: 359.22 mg/l, SD 551.89, n = 27). A comparison of means showed a higher cumulative dose of steroids (1035 versus 826 mg/kg or 937 compared versus 777 mg/kg) in patients with high LDL mean: 130 mg/dl, range: 58–216, SD 40 mg/dl, n = 27, or a low HDL/LDL quotient, respectively. Only one of the forty-three patients developed insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus during the sixth relapse of NS at 7 years of age. Blood sugar (n = 30) or HbA1c (n = 27) was normal in all the cases.

At NS onset, one patient, aged 3 years developed a left-side cerebral vascular thrombosis with hemiplegic symptoms under steroid treatment. At the FUV, this patient had a restriction of motion of the right upper limb. No patient was treated prophylactically with aspirin, heparin, or warfarin.

In total, 14 patients had the diagnosis of arterial hypertension (AH). Seven patients were treated with antihypertensive drugs, eight patients had elevated blood pressure values but were not treated. There was no significant correlation between AH and the number of relapses, cumulative steroid dose, or cumulative period of onset and relapse. In addition, there was no significant correlation between AH and hypercholesterolemia or increased lipoprotein (a). One patient died due to a stroke in adulthood. Two patients (4.7%) suffered from a heart attack, one at the age of 30 and one at 43 years of age.

Thirty-four of forty-three (79.1%) children developed a steroid-induced Cushing. Striae distensae were observed in 8 cases (18.6%) and AH was diagnosed in 5 of 43 (11.6%) children. Four of 5 patients with AH in childhood had also an AH in adulthood.

Hypertrichosis was observed in 3 children (5.9%). One patient developed hemorrhagic cystitis due to the cyclophosphamide treatment. Cataracts were diagnosed in 3 patients (7%), and hypertensive retinopathy in 2 cases (8%) (n = 25). There were no malignancies reported by the patients (Table 9S, supplemental material). In summary, the psychosocial outcomes were excellent. No patient was under a psychotherapeutic treatment or took any psychotropic drugs.

Immunology, allergy, and inflammation

Anamnestically, 22 of 40 patients (55%) reported to suffer from allergies. Immunoglobulin E (IgE) in serum (n = 30) was between 115 and 2950 IU/ml (Mean = 380 IU/ml) and increased in 13 cases (43%) (normally < 100 IU/ml). Elevated IgE values at FUV did not correlate with a complicated course of the disease (frequent relapses, high total number of relapses, disease duration or cumulative onset, and relapse period).

Growth and weight

The mean height of male patients ≥ 18 years at FUV was 1.78 m (1.68–1.90 m, n = 41) and of females was 1.67 m (1.56–1.84 m, n = 12). The difference of the calculated height to the genetic target size varied from − 11.3 to + 19 cm (Median: 1.3 cm; n = 37).

The mean body mass index (BMI) of males was 25.2 kg/m2 (17.1–33.0, n = 30) and of females was 26.3 kg/m2 (19.6–47.3, n = 13). One patient was underweight (BMI = 17.1 kg/m2), 22 subjects had a normal-weight (BMI = 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), 15 (12 males, 3 females) were overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2), and 5 (3 males, 2 females) had an obesity (BMI > 30.0 kg/m2).

Immunosuppressive therapy and family planning, fertility, and pregnancy

The number of steroids in n = 43 is, on average, 23,274 mg (range 1654–130,170 mg), based on the weight: 744 mg/kg (51–3795 mg/kg). The given dose of cyclophosphamide is, on average, dose of 6875.8 mg and 210 mg/kg (n = 11). For cyclosporine A, the average total dose is 384728.3 mg and 8105 mg/kg (n = 5), for chlorambucil 226.3 mg and 8.1 mg/kg (n = 6), and for MMF, it is 1,483,083 mg and 23,670 mg/kg (n = 3).

Eighteen of 41 patients > 18 years age (12 males) had a total of 31 biological children. None of these children have developed SSNS. Two males reported undesirable childlessness. One male patient had a fertility disorder—presumably due to the cytostatic treatment. Another patient had oligo- and asthenozoospermia [cyclophosphamide (2 mg/kg; cumulative dose: 3429 mg and 104 mg/kg) and chlorambucil (0.15 mg/kg; cumulative dose: 342 mg bzw. 9 mg/kg) intake over 8 weeks at the age 11–12 years]. Of the 9 males treated with cyclophosphamide, one had 2 and one had 3 children. They received the drugs at the age of 13 and 15 years, respectively, over one period of 9–10 weeks at doses of 0.8–5.3 mg/kg (50–250 mg/day; cumulative dose 13,050 mg/224 mg/kg and 13,700 mg/291 mg/kg). Six female patients had children (3 × 1 child, 2 × 2 children, 1 × 3 children). Pregnancy and birth were without any complications for five female patients.

Results of SRNS

Seven of 50 patients (14%) developed SRNS or were primarily steroid-resistant. The sex ratio was 1.3–1 (male–female). Five patients had German heritage; one patient had Polish heritage, and one Kazakhstani heritage. Histologically, the first renal biopsy in 3 cases showed minimal change nephrotic syndrome (MCNS). Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) was seen in 3 cases, and membranous nephropathy (MG) was present in one case. The mean age at onset was 4.6 ± 4.38 years and the mean age at FUV was 27.5 ± 9.9 years. Four of 7 patients of SRNS had a good outcome without a chronic kidney disease, and 3 of 7 patients had received a kidney transplantation. Three of four patients who did not require a kidney transplant had no more relapses in adulthood. One 14-year-old patient with MG still experienced relapses at the time of the FUV. The renal function parameters (either biochemical or sonographically) in all patients were within the normal ranges. Strikingly, a high proportion of patients had AH.

All transplanted patients histologically had FSGS. All patients that received transplants were hemodialyzed before transplantation for at least 1 or more year/s. One patient received a second transplant due to thrombosis 10 years after the first transplant. Transplanted patients also had several other diagnoses such as AH (n = 3) hypertensive retinopathy (I–III) (n = 3), osteoporosis (n = 2), renal growth failure (n = 1), and a labile depression (n = 1). An adequate renal function of the transplanted kidney was present in all the patients. In summary, no patient developed disease recurrence in the transplant.

Discussion

Clinical course of disease

SSNS in childhood has a good prognosis. The outcome of NS without recurrent relapses in adulthood is positive [7]. In our study, 12 patients (27.9%) were infrequent relapsers; 31 patients (72.1%) were frequent relapsers. Only 4 of 41 patients had relapses beyond the age of 18 years. Similar to the present study, Siegel et al. showed that 16.5% of their patients with NS had no relapses during the clinical course [10]. A few studies focusing on the long-term outcome of NS in adulthood have shown rates of relapses in adulthood is between 33 and 42.4% [11, 12]. However, we report that approximately 9.8% of our patients suffered from recurrent relapses in adulthood.

In the study by Trompeter et al., 5.5% of their study cohort diagnosed with NS before the age of 6 years still had SSNS relapses in adulthood [13], which is similar to our findings of 3.1%. Tarshish et al. also showed that 5–10% of patients had relapses in follow-up examinations, although only very few patients were “frequent relapsers” [7].

The necessity of cytostatic medications is a useful parameter to evaluate the severity of the disease processe. In our study, only 12 of 43 (27.9%) of patients received cytostatic medications; in comparison to other studies, 49% [11], 57% [12], or 72% [14] of patients received cytostatic medications.

In conjunction with the previous literature, 75% patients in this study with relapses in adulthood had also suffered from one relapse within the first 6 months after onset. However, the early relapses (within first 6 months after onset) are not described in the literature as a risk factor for the occurrence of relapses in adulthood [11, 12], but have been described as a risk factor for a serious clinical course. It was not possible to confirm if patients with relapses in adulthood exhibited a longer cumulative duration of NS since onset, more relapses, frequent relapses, or a cumulative amount of steroids or a more serious clinical course. Furthermore, renal function, cardiac diseases, and osteoporosis were not different between those who relapsed in adulthood and those that did not. Given the low number of patients who relapsed in adulthood, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Gender

The gender distribution of our patients with SSNS was 2.3–1 (male–female), and 1.3–1 for SRNS (male–female). The relationship between gender and a complicated clinical course is controversial. In the study by Lewis et al., a larger number of boys had significantly more relapses per year than girls, and in affected males, a tendential relationship was observed, showing that the frequency and duration of relapses were associated [14]. However, Schwartz et al. did not detect any correlation between the gender and prognosis [15]. Similarly, no significant correlation between gender and the frequency of relapses was observed in this study.

Birth Weight

Zidar and Sheu et al. showed a significant correlation between the intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) and unfavorable course of NS, primarily in children with MCNS [16, 17]. Other authors have also described that a low birth weight is correlated with a higher morbidity in adulthood. Specifically, the relationship between low birth weight and an increased risk for the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases, AH, and diabetes mellitus type II in adulthood was presented in these studies [18,19,20]. In the study by Sheu et al., the serum cholesterol and triglycerides in children with IUGR were significantly higher than in children without IUGR [17]. Several authors have shown that IUGR or a low birth weight (< 2500 g) may lead to a reduced number of nephrons [21,22,23]. There is a linear correlation between the number of nephrons and the birth weight [22]. In the present study, only the birth weight and not the gestational age were documented; therefore, it was not possible to draw conclusions about the IUGR in our study cohort. However, a tendency for an unfavorable clinical course in patients with a birth weight ≤ 3000 g was observed. However, a significant correlation between the birth weight and dyslipidemia and AH was not detected.

Renal function

Except for a slight reduction in one case, the renal function was not restricted in patients with SSNS. In previous studies of patients with idiopathic SSNS, the long-term kidney function has been shown to be normal [24, 25]. Koskimies et al. showed that all patients with primary NS with steroid treatment had no proteinuria within 8 weeks after therapy and had a normal kidney function in clinical course [26]. Fakhouri et al. showed that only 1 of 43 patients with relapses in adulthood developed an end-stage-renal disease [11]. Thus, the long-term renal function prognosis in children with SSNS is positive. These results are in contrast to those from a recent study by Calderon-Margalit et al., which examined the long-term risk associated with childhood kidney disease and a risk of future development of end-stage renal disease in a nationwide, population-based historical cohort of 1,521,501 Israeli adolescents over a 30-year period.

Conclusively, these patients with a history of kidney disease in childhood but with a normal renal function in adolescence were presented to have a significantly increased risk of ESRD [27].

Bone metabolism

Leonard et al. examined the bone density in children with SSNS and no link between diminished bone density and intermittent glucocorticoid treatment during childhood was shown [28]. In our study, bone-density measurement in two patients and elevated DPD values in urine and bone-specific AP in serum indicate a tendency to bone metabolic disorders. However, these parameters are not significantly correlated with a high steroid dose or a severe clinical course. Weng et al. detected lower 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in the serum in children with SSNS in remission. In contrast, most adult patients were in remission in the current study (95.3%). Only 6.9% of the cohort (2 of 29 patients) had a vitamin D deficiency (< 10 ng / ml) in contrast to 19.5% in the study by Weng et al. [29].

Cardiovascular system

Surprisingly, the proportion of patients with elevated cholesterol and lipoprotein (a) levels was high. These values are not significantly associated with a high-dose steroid therapy. Worldwide, childhood obesity is increasing, and, thus, associated lipid metabolic disorders are commonly more observed [30]. Dyslipidemia is also mostly observed during the disease period of NS. There are multiple clinical consequences of lipid metabolic disorders in children with nephrotic syndrome, e.g., atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and stroke, as well as, an increased risk in developing thromboembolisms [31]. The prevalence of dyslipidemia changed between 10.7 and 69.9% in children with obesity in different populations [32]. The study of Korsten-Reck et al. (2008) has even reported a dyslipidemia incidence of 45.8% in German children [33]. Mérouani et al. (2003) analyzed the plasma lipid profiles in their study cohort with NS at disease remission and the data were compared with an age-matched study population. The results showed that (total and LDL) cholesterol levels were over than the 95. percentile in 48% of cases, and 7 of 12 patients have even high apolipoprotein B and triglyceride levels which conclude that children suffering from frequently relapsing were more likely to have pathologic lipid profile levels during the remission period [34]. Kniazewska et al. showed that patients with SSNS had a significantly increased total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, homocysteine, as well as, apolipoprotein A1 and B after treatment. Moreover, a positive correlation between the number of relapses and ultrasonographically determined thickness of the intima media of the common carotid artery has previously been established [35].

Furthermore, the high proportion of patients in the present study with AH was remarkable (32.6%), but not related to the severity of the disease or the type of immunosuppressive therapy. In the study by Fakhouri et al., 3 of 43 patients with relapses in adulthood had AH [11]. In the study by Koskimies et al., all patients who had steroid therapy were free from proteinuria within 8 weeks after treatment and had normal blood pressure values from 5 to 14 years after onset at an FUV [26].

Height and BMI

The final height in this study was − 0.2 SDS (age range from 18 to 50 years), which is in line with the previous literature, showing that 179 patients with SSNS reached a mean final height of − 0.2 to − 0.5 SDS [36, 37]. None of the present cohort had short stature. However, in studies by Rüth et al. and by Fakhouri et al., respectively 1 of 42 (2.4%) and 6 of 36 (16%) patients with relapses in adulthood had a short stature.

In the present cohort, 15 of 43 patients (34.9%) were overweight (BMI ≥ 25 to 30 kg/m2) and 5 of 43 patients (11.6%) were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). In comparison, 8 of 42 patients were overweight and 1 of 42 patients obese in the study conducted by Rüth et al. [12], and 8 of 43 patients were obese in the study by Fakhouri et al. [11]. As in the study of Rüth et al., the present study did not show any significant correlation between BMI and the cumulative steroid dose or cumulative duration of onset and relapse [12]. Foster et al. analyzed the risk factors of a steroid-induced adiposity in children in patients with SSNS and detected a significant correlation between recent steroid intake and obesity [38]. In the current cohort, only 3 of 43 patients (7%) were under steroid therapy at FUV.

Allergies and IgE

SSNS is frequently associated with allergies, bronchial asthma, allergic rhinitis, or atopic dermatitis [39]. Atopy is seen in up to 30% of cases with idiopathic NS [40]. In the current-study population, more than 55% patients suffered from allergies, and 43% of patients with SSNS had an increased serum IgE. There was no correlation between increased IgE at the FUV and a complicated course of SSNS. In contrast, increased serum IgE values in children with NS were associated with a complicated clinical course shown in the study by Hu et al. (frequent relapses or poor response to steroid therapy) [41]. However, it is still unclear whether raised levels of IgE in children with idiopathic NS can be attributed to a pathogenic or coincident role [39]. It is likely that changes in the immune system in patients with SSNS may be a predisposition for allergies [42].

Steroid-induced cataracts

The long-term use of steroids in childhood NS is associated with ophthalmologic complications including cataract. Based on the data of the World Health Organization, cataracts are the leading cause of blindness, in which almost around 24 million people are affected [43]. The posterior subcapsular opacification is the classic location for steroid-induced lens changes. A similar percentage of patients in this study, 12.6% of patients developed a posterior subcapsular opacity. Brocklebank et al. showed no significant correlation between the cumulative steroids dose or the duration of therapy and developing of cataract [44].

Fertility and pregnancy

In the current cohort, 21 of 43 patients were married, 3 were divorced, and 19 patients were single. Eighteen of 41 patients > 18 years age (12 males) had a total of 31 biological children. Only 2 male patients reported an undesirable childlessness (one of these patients was treated with cyclophosphamide and chlorambucil in the past). Multiple studies have previously presented a link between the cytotoxic therapy effect in SSNS and impaired male fertility [45,46,47,48,49]. A cumulative dose of cyclophosphamide less than 20 g or 540 mg/kg is not associated with oligo- or azoospermia [45]. However, a cumulative dose of chlorambucil of 9 mg/kg is associated with a severe oligospermia [46]. Compared to studies that analyzed the correlation between the cumulative dose and fertility disorder, chlorambucil therapy could be the most likely reason of childlessness in our above-mentioned patient. Furthermore, Rüth et al. found a correlation between the cyclophosphamide therapy and childlessness, whereby, patients with two or more cycles of cytostatic therapy had a significantly higher risk of childlessness than patients with a single cycle [12].

Steroid-sparing immunosuppressants

In summary, NS in childhood is characterized by a frequent relapsing course and there is currently no uniform agreement about the precise stage at which a steroid-sparing agent should be introduced to control the disease. Many steroid-sparing immunosuppressants [e.g., calcineurin inhibitors, MMF and levamisole] are also common treatment alternatives for patients with frequently relapsing and steroid-dependent NS. One retrospective study showed that tacrolimus was more effective than MMF or levamisole in maintaining a survival without relapses, but MMF is also a safe and effective alternative to Tacrolimus in controlling the clinical course of frequently relapsing and steroid-dependent NS [50].

Limitations

The present study is a retrospective analysis with a subsequent follow-up examination and interview of patients who had childhood NS. In most retrospective analyses, there is an incomplete data set due to missing or inaccurate file entries. In addition, due to the long period of the first manifestation (1957–1995) and the changing therapy recommendations during this period, a heterogeneity of the therapeutic interventions has to be noted. In addition, the low patient number with a high heterogeneity, and thereby the limited reliability of data present the major limitation of the study.

Conclusion

The renal outcome in our study was very good and no patient with SSNS had chronic renal failure at time of FUV. Thus, one-third of patients with SSNS in childhood had elevated blood pressure values or were already under antihypertensive treatment. Other sequelae, possibly due to the therapy, are osteoporosis, obesity, and hyperlipoproteinemia. There was no correlation between the development of AH and a complicated course of NS; nor any correlation between AH and hypercholesterinemia or an increase in the lipoprotein (a). Despite the good prognosis, an early onset and males present a risk for a longer disease course and frequent relapses. A tendency to lipid metabolism disorders, AH, and a high prevalence of allergies, and an increased serum IgE were noticeable; however, there was no correlation with the severity of renal disease. The psychosocial outcomes were outstanding. At FUV, no patient was in psychotherapeutic treatment or under therapy with psychotropic drugs.

In summary, this novel study shows the long-term outcomes of patients diagnosed with SSNS in childhood during a follow-up period of up to 30 years. Primary nephrotic syndrome is a chronic, but benign disease with a good long-term prognosis. This study will be helpful to reduce the anxiety of parents when their child receives an NS diagnosis.

Availability of data and material

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from Dr. I. Franke/ Dr. R. Hagemann on reasonable request at Department of General Pediatrics, University Children’s Hospital Bonn, Germany, and will be shared with scientists/researcher upon request to Dr. I. Franke or Dr. R. Hagemann.

Abbreviations

- AH:

-

Arterial hypertension

- AP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DPD:

-

Deoxypyridinoline

- ESPED:

-

Erhebungseinheit für seltene pädiatrische Erkrankungen in Deutschland

- FSGS:

-

Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

- FUV:

-

Follow-up visit

- M:

-

Mean

- MCNS:

-

Minimal change nephrotic syndrome

- MG:

-

Membranous glomerulonephritis

- NS:

-

Nephrotic syndrome

- SSNS:

-

Steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome

- SRNS:

-

Steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome.

References

International Study of Kidney Disease in Children/ISKDC. The primary nephrotic syndrome in children. Identification of patients with minimal change nephrotic syndrome from initial response to prednisone. J Pediatr. 1981;98:561–4.

Nash MA, Edelmann CM Jr, Bernstein J, Barnett HL. Minimal change nephrotic syndrome, diffuse mesangial hypercellularity and focal glomerulosclerosis. In: Edelmann CM Jr, editor. Pediatric kidney disease. 2nd ed. Boston: Little, Brown; 1992. pp. 1267–90.

Hussain N, Zello JA, Vasilevska-Ritovska J, Banh TM, Patel VP, Patel P, et al. The rationale and design of Insight into Nephrotic Syndrome: Investigating Genes, Health and Therapeutics (INSIGHT): a prospective cohort study of childhood nephrotic syndrome. BMC Nephrology. 2013;14:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2369-14-25.

Franke I, Aydin M, Llamas Lopez CE, Kurylowicz L, Ganschow R, et al. The incidence of the nephrotic syndrome in childhood in Germany. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018;22(1):126–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-017-1433-6.

Bagga A, Mantan M. Nephrotic syndrome in children. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:13–28.

International Study of Kidney Disease in Children/ISKDC. Early identification of frequent relapsers among children with minimal change nephrotic syndrome. J Pediatr. 1982;101:514–8.

Tarshish P, Tobin JN, Bernstein J, Edelmann CM Jr. Prognostic significance of the early course of minimal change nephrotic syndrome: report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:769–76.

Broyer M, Meyrier A, Niaudet P, Habib R. Minimal changes and focal segmental glomerular sclerosis. In: Davison AM, editor. Oxford textbook of clinical nephrology. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford university Press; 1998. pp. 493–535.

Gipson DS, Chin H, Presler TP, et al. Differential risk of remission and ESRD in childhood FSGS. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:344–9.

Siegel NJ, Goldberg B, Krassner LS, Hayslett JP. Long-term follow-up of children with steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome. J Pediatr. 1972;81:251–8.

Fakhouri F, Bocquet N, Taupin P, Presne C, Gagnadoux MF, Landais P, Lesavre P, Chauveau D, Knebelmann B, Broyer M, Grünfeld JP, Niaudet P. Steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome: from childhood to adulthood. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41:550–7.

Rüth EM, Kemper MJ, Leumann EP, Laube GF, Neuhaus TJ. Children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome come of age: long-term outcome. J Pediatr. 2005;147:202–7.

Trompeter RS, Lloyd BW, Hicks J, White RH, Cameron JS. Long-term outcome for children with minimal-change nephrotic syndrome. Lancet. 1985;1:368–70.

Lewis MA, Baildom EM, Davis N, Houston IB, Postlethwaite RJ. Nephrotic syndrome: From toddlers to twenties. Lancet. 1989;1:255–9.

Schwartz MW, Schwartz GJ, Cornfeld D. A 16 year follow up study of 163 children with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatrics. 1974;54:548–52.

Zidar N, Cavic MA, Kenda RB, Ferluga D. Unfavorable course of minimal change nephrotic syndrome in children with intrauterine growth retardation. Kidney Int. 1998;54:1320–3.

Sheu JN, Jeun-Horng C. Minimal Change Nephrotic Syndrome in Children with Intrauterine Growth Retardation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:909–14.

Barker DJP, Bull AR, Osmond C, Simmonds SJ. Fetal and placental size and risk of hypertension in adult life. BMJ. 1990;301:259–62.

Barker DJP, Winter PD, Osmond C, Simmons SJ. Weight in infancy and death from ischemic heart disease. Lancet. 1989;2:577–80.

Hales CN, Barker DJP, Clark PMS, Cox LJ, Fall C, Osmond C, Winter PD. Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64. BMJ. 1991;303:1019–22.

Hinchliffe SA, Lynch MR, Sargent PH, Howard CV, Van Velzen D. The effect of intrauterine growth retardation on the development of renal nephrons. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:296–301.

Hughson M, Farris AB 3rd, Douglas-Denton R, Hoy WE, Bertram JF. Glomerular number and size in autopsy kidneys: the relationship to birth weight. Kidney Int. 2003;63:2113–22.

Manalich R, Reyes L, Herrera M, Melendi C, Fundora I. Relationship between weight at birth and the number and size of renal glomeruli in humans: a histomorphometric study. Kidney Int. 2000;58:770–3.

Matsukura H, Inaba S, Shinozaki K, Yanagihara T, Hara M, Higuchi A, Takada T, Tanizawa T, Miyawaki T. Influence of prolonged corticosteroid therapy on the outcome of steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome. Am J Nephrol. 2001;21:362–7.

Motoyama O, Iitaka K. Final height in children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatrics Int. 2007;49:623–5.

Koskimies O, Vilska J, Rapola J, Hallmann N. Long-term outcome of primary nephrotic syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1982;57:544–8.

Calderon-Margalit R, Golan E, Twig G, Leiba A, Tzur D, Afek A, et al. History of childhood kidney disease and risk of adult end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(5):428–38.

Leonard MB, Feldman HI, Shults J, Zemel BS, Foster BJ, Stallings VA. Long-term, high-dose glucocorticoids and bone mineral content in childhood glucocorticoid sensitive nephrotic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:868–75.

Weng FL, Shults J, Herskovitz RM, Zemel BS, Leonard MB. Vitamin D insufficiency in steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome in remission. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:56–63.

Truthmann J, Mensink GBM, Bosy-Westphal A, Scheidt-Nave C, Schienkiewitz A. Metabolic Health in Relation to Body Size: Changes in Prevalence over Time between 1997-99 and 2008-11 in Germany. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0167159.

Agrawal S, Zaritsky JJ, Fornoni A, Smoyer WE. Dyslipidaemia in nephrotic syndrome: mechanisms and treatment. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14(1):57–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneph.2017.155.

Elmaoğulları S, Tepe D, Uçaktürk SA, Karaca Kara F, Demirel F. Prevalence of dyslipidemia and associated factors in obese children and adolescents. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2015;7(3):228–34.

Korsten-Reck U, Kromeyer-Hauschild K, Korsten K, Baumstark MW, Dickhuth HH, Berg A. Frequency of secondary dyslipidemia in obese children. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(5):1089–94.

Mérouani A, Lévy E, Mongeau J-J, Robitaille P, Lambert M, Delvin EE. Hyperlipidemic profiles during remission in childhood idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Clin Biochem. 2003;36:571–4.

Kniazewska MH, Obuchowics AK, Wielkoszyński T, Zmudzińska-Kitczak J, Urban K, Marek M, Witanowska J, Sieroń-Stołtny K. Atherosclerosis risk factors in young patients formerly treated for idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24:549–54.

Emma F, Sesto A, Rizzoni G. Long-term linear growth of children with severe steroid responsive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18:783–8.

Foote KD, Brocklebank JT, Meadow SR. Height attainment in children with steroid responsive nephrotic syndrome. Lancet. 1985;2:917–9.

Foster BJ, Shults J, Zemel BS, Leonard MB. Risk factors for glucocorticoid-induced obesity in children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:973–80.

Salsano ME, Graziano L, Luongo I, Pilla P, Giordano M, Lama G. Atopy in childhood idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Acta paediatrica. 2007;96:561–6.

Meadow SR, Sarsfield JK, Scott DG, Rajah SM. Steroid-responsive nephrotic syndrome and allergy: immunological studies. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56:517–24.

Hu JF, Liu YZ. Elevated serum IgE levels in children with nephrotic syndrome, a steroid-resistant sign? Nephron. 1990;54:275.

Abdel-Havez M, Shimada M, Lee PY, Johnson RJ, Garin EH. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome and atopy. Is there a common link? Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54(5):945–53.

Mundy K, Nichols E, Lindsey J. Socioeconomic disparities in cataract prevalence, characteristics, and management. Semin Ophthalmol. 2016;31(4):358–63.

Brocklebank JT, Harcourt RB, Meadow SR. Corticosteroid-induced cataracts in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Arch Dis Childhood. 1982;53:30–4.

Bogdanovic R, Banicevic M, Cvoric A. Testicular function following cyclophosphamide treatment for childhood nephrotic syndrome: long-term follow-up study. Pediatr Nephrol. 1990;4:451–4.

Callis L, Nieto J, Vila A, Rende J. Chlorambucil treatment in minimal lesion nephrotic syndrome: a reappraisal of its gonadal toxicity. J Pediatr. 1980;97:653–6.

Guesry P, Lenoir G, Broyer M. Gonadal effects of chlorambucil given to prepubertal and pubertal boys for nephrotic syndrome. J Pediatr. 1978;92:299–303.

Penso J, Lippe B, Ehrlich R, Smith FG. Testicular function in prepubertal and pubertal male patients treated with cyclophosphamide for nephrotic syndrome. J Pediatr. 1974;84:831–6.

Rapola J, Koskimies O, Huttunen NP, Floman P, Vilska J, Hallmann N. Cyclophoshamide and the pubertal testis. Lancet. 1973;1:98–9.

Basu B, Babu BG, Mahapatra TK. Long-term efficacy and safety of common steroid-sparing agents in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2017;21(1):143–51.

Acknowledgements

***Ingo Franke †*** We thank our first author, colleague, and friend Ingo Franke for his excellent work in the field of Pediatric Nephrology in Germany. He taught us very enthusiastically, and he was a great pediatrician and researcher. Rest in Peace, dear Ingo! This publication should confirm your effort, your invested time, and energy. We all miss you!

Funding

This study was not funded by any private or institutional organizations/firms.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IF and RH designed and performed the study. MA, MB, LK, RH, and IF performed the literature search, extracted data, and drafted the manuscript. ML and RG participated in manuscript writing and revision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that they have no competing interests. This work has not been published before and it is not under consideration for publication anywhere else. Its publication has been approved by all co-authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All retrospectively and prospectively analyzed data involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethical approval was obtained by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-University, Bonn, Germany, and the study was assigned the human study registration number 081/05. The data extraction and analyses were performed pseudonymously; an additional participant informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Aydin, M., Franke, I., Kurylowicz, L. et al. The long-term outcome of childhood nephrotic syndrome in Germany: a cross-sectional study. Clin Exp Nephrol 23, 676–688 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-019-01696-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10157-019-01696-8