Abstract

One of the impediments in the genetic improvement of cotton fiber is the paucity of information about genes associated with fiber development. Availability of chromosome arm substitution line CS-B22sh (chromosome 22 short arm substitution from 3–79 (Gossypium barbadense) into a TM-1 (Gossypium hirsutum) background) provides a novel opportunity to study fiber-associated genes because previous studies revealed this line was associated with some superior fiber quality traits compared to TM-1. We used an integrated approach of suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH), microarray, and real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technologies to identify the potential genes associated with fiber development. Utilizing mRNAs from 15 days post-anthesis (dpa) fibers, we constructed a SSH cDNA library with chromosome substitution line CS-B22sh as the tester and TM-1 as the driver. The SSH cDNA library was screened using microarrays. Microarray analysis showed that 36 genes were differentially expressed in CS-B22sh 15-dpa fiber compared to TM-1 as confirmed by real time RT-PCR. These genes include two beta-tubulins, an actin, a putative kinesin light chain, a cellulose synthase, glycosyl hydrolase family 3 protein, pyruvate decarboxylase, glycoside hydrolase family 5, GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase, dynamin-like protein, annexin, and a number of genes involved in signal transduction, and protein, nucleic acid, and lipid metabolisms. To our knowledge, this is the first report on identification of differentially expressed fiber-associated genes in a cotton chromosomal substitution line.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cotton (Gossypium) is the leading natural fiber crop and the second most important oilseed in the world (Basra and Malik 1984). The U.S. is the world’s most reliable producer of high quality cotton, providing about 55% of all fiber used in textiles (Tomkins et al. 2001). Contributing about $5.5 billion per year directly to the U.S. economy, cotton is among the top five agronomic crops and the predominant industrial crop. The U.S. commonly supplies 7 million bales or more of the world’s cotton exports. Over 300,000 workers are employed in the U.S. alone due to the cotton crop, and cotton has business revenue of $122.4 billion, the greatest of any U.S. crop (National Cotton Council 2005). However, yield and fiber quality have declined over the last decade (Meredith 2000). Competition from synthetic fiber and widespread use of high speed spinning technology require improvement in cotton fiber quality and quantity.

Traditional cotton breeding methods have faced many challenges including the limited information on the important genes associated with fiber traits. Identification and characterization of cotton fiber-associated genes is critical for genetic manipulation to improve fiber traits using molecular approaches. The high value per hectare of cotton and the demands in the global market for increased uniformity, strength, extensibility, and high quality of fibers clearly justify the importance of new and innovative approaches toward evaluating and understanding the controlling mechanisms behind fiber qualities. One of the overriding long-term objectives of this research was to utilize advance genomic technologies to discover genes associated with economically important fiber traits and thus benefit in the genetic manipulation of complex fiber traits for improved fiber qualities. The exceptional fiber length, strength, and fineness (micronaire) of Pima and Sea Island cotton (Gossypium barbadense L) give it a 30 to 50% price advantage over the more widely grown Upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L) because of its superior spinning and manufacturing performance. Recently, Stelly et al. (2005) released 17 backcrossed chromosome substitution lines (CS-B) for different chromosome and chromosome segments of G. barbadense. These lines are genetically identical except that each differs by the replacement of a specific homologous pair of chromosomes from 3–79 (G. barbadense) into the Upland (TM-1) background. They also provided information about the improved fiber traits associated with these lines (Saha et al. 2004; Saha et al. 2006; Jenkins et al. 2007). A previous study revealed that chromosome arm substitution line CS-B22sh, a line with chromosome 22 short arm substitution from 3–79 (Gossypium barbadense) into a TM-1 (G. hirsutum) background, was associated with many important fiber traits including lint percentage, micronaire, 2.5% span length (Saha et al. 2006). Jenkins et al. (2007) used CS-B22sh line in top crosses with Upland cultivars and detected that CS-B22sh line had positive additive effect on micronaire and negative additive effect on 2.5% span length and strength. They also reported that CS-B22sh had positive homozygous dominance effect on fiber strength. Scientists also reported Li-1, a mutant that produced only short fibers, was located on the short arm of chromosome 22 (Karaca et al. 2002; Rong et al. 2005). Recently, several SSR marker-based molecular maps also revealed that several important fiber traits are located on the short arm of chromosome 22 in cotton (Han et al. 2004, 2006; Nguyen et al. 2004; Lacape et al. 2005; Park et al. 2005; Song et al. 2005; Frelichowski et al. 2006; Guo et al. 2007). Therefore, availability of chromosome arm substitution line CS-B22sh, provides a novel opportunity to identify and isolate genes associated with fiber development. This is important considering the results from previous studies suggesting that CS-B22sh, line had some important fiber quality traits compared to the TM-1 parent (Saha et al. 2006; Saha et al. 2004; Jenkins et al. 2007). Hence, identification of differentially expressed genes in CS-B22sh may provide some valuable information and tools for understanding the mechanisms of fiber development and for improving cotton fiber qualities.

Cotton fibers are differentiated seed epidermal cells. Cotton fiber growth traditionally occurs in four phases: initiation, elongation, secondary cell wall thickening, and maturation, and each of the developmental phases overlaps the succeeding phase (Basra and Malik 1984; Wilkins and Jernstedt 1999). Fiber initiation begins just 1 or 2 days before anthesis and involves the initial protrusion and isodiametric expansion of the epidermal cell above the ovule surface. Fiber elongation starts at anthesis and lasts for about 25 dpa in most cases. Although numerous ESTs and some genes from developing cotton fiber have been isolated, the function is known only for a few of these genes (Kim and Triplett 2001; Wilkins and Jernstedt 1999). Previously, we isolated and characterized several genes differentially expressed in 20-dpa fiber of 3–79 (G. barbadense), a high fiber-quality species (Wu et al. 2005).

The most widely used methods for gene identification and isolation often rely on examining differential gene expression in varied experiments under varied growth conditions. Patterns of gene expression can be compared using differential hybridization screening (Tedder et al. 1988), representational difference analysis (RDA) (Lisitsyn et al. 1993), serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) (Velculescu et al. 1995), differential display (DD) (Liang and Pardee 1992), and subtractive library construction (Hedrick et al. 1984). Such techniques are tedious, labor-intensive, and time-consuming. Some require a large amount of mRNA (cDNA), have high levels of false positives, or are biased for high abundance mRNA. The application of SSH, cDNA microarrays and real time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technology offers the possibility of providing a rapid, high throughput method to identify differentially expressed genes. Here, we utilized SSH, cDNA microarrays, and real time RT-PCR as a means of identifying differentially expressed genes in CS-B22sh, and this would provide useful information to understand gene functions in cotton fiber development.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Plants of G. hirsutum accession TM-1 and CS-B22sh were grown in the field in Starkville, MS in the summer of 2004. Flowers were tagged and dated the day they opened as 0-day post-anthesis (dpa) and collected on 15 dpa. Ovules were removed and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. The fiber layer was then scraped from the developing ovule with a scalpel and a forceps under liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C.

RNA isolation

Total RNA of CS-B22sh and TM-1 was extracted from 15-dpa fibers according to the previously described method (Wan and Wilkins 1994). Poly (A)+ mRNA was isolated from the total RNA with an mRNA Purification Kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) according to the vendor’s instructions.

Construction of SSH cDNA library

The PCR-Select cDNA subtraction Kit (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) was used to generate the SSH cDNA sequences according to the vendor instructions. Different preparations of RNA samples from the CS-B22sh and TM-1 15-dpa fiber tissues collected from different blocks in a random complete block design in the field were pooled, respectively. The cDNA was reversely transcribed from 2 μg of fiber mRNA of CS-B22sh and TM-1, respectively. SSH library was constructed using CS-B22sh fiber cDNA as tester and TM-1 fiber cDNA as driver. Tester and driver cDNA were digested with Rsa I, extracted with phenol/chloroform, precipitated with ethanol, and resuspended in water. The digested tester cDNA was ligated with different adaptors provided in the cDNA subtraction kit. Two rounds of hybridization and PCR amplification were conducted to enrich the differentially expressed cDNA sequences. The final PCR products were purified, inserted directly into the T/A cloning vector, and transformed into Escherichia coli TOP10 cells using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), producing the SSH cDNA library.

PCR amplification of cDNA inserts

Four hundred and eighty cDNA clones were randomly selected from the SSH library. The clones were grown overnight at 37°C, and then, amplified with M13 forward and reverse primers complementary to sequences flanking the cloning site. The amplification of cDNA inserts was carried out in GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The 30-μl PCR reaction mixtures contained 18.8 μl of water, 0.3 μl of each M13 forward and reverse primers (10 μM each), 6 μl of 5× Go Taq buffer, 3.0 μl of dNTP mix (2.5 each), 0.2 μl (1 U) of Go Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and 1 μl of bacterial culture. The clones were denatured at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 2 min, with final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR fragments were analyzed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and then, quantified using a spectrophotometer.

cDNA microarray slide preparation

cDNA microarray slide preparation and microarray analysis for the selected SSH cDNA clones was carried out in the Genomics Core Facility, University of Alabama at Birmingham, AL, USA. The PCR products from the SSH cDNA clones were spotted onto Ultra GAPs slides (Corning Biosciences, Corning, NY, USA) using an OmniGrid 100 contact printer. On average, 200–300 pg of the amplified SSH fragments were spotted. Each cDNA clone was printed in triplicate in 3× standard saline citrate (SSC) printing solution.

Microarray hybridization and analysis

The isolated total RNA samples from the CS-B22sh and TM-1 fiber tissues collected from different blocks in a random complete block design was pooled, respectively, and then, labeled with Cy Dyes using the LabelIT microarray Cy3/Cy5 labeling kit as per the manufacture’s instructions (Mirus, Madison, WI, USA). The TM-1 RNA was labeled with Cy3, and the CS-B22sh RNA was labeled with Cy5. One dye flip experiment was conducted to correct for any dye bias. The independent labeling reactions were combined and concentrated using the Microcon YM30 columns (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Before hybridization, the slides were rehydrated in 3× SSC, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) at 65°C for 5 min followed by a rinse in water, then in 95% ethanol and spun dried at 50 g for 2 min. The slides were cross-linked by UV at 200 mJ in a Stratalinker (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Prehybridization of the slides was done in 25% Formamide, 5× SSC, 0.1% SDS, and 1% BSA at 48oC for 60 min. The slides were dipped in water followed by isopropanol and spun dried at 50 g for 2 min. To hybridize the slides, the concentrated probes were brought to a final volume of 18 and 2 μl of polyA (10 mg/ml), and 2 μl of yeast tRNA (10 mg/ml) were added. Hybridization buffer (2×, 20 μl) was added (10× SSC, 50% Formamide, 0.2%SDS), and the probes were heated to 70°C for 5 min to remove any secondary structure and then equilibrated to 48°C for 1 min. The labeled probes were applied to the slides and covered with a lifter slip (Erie Scientific, Portsmouth, NH, USA), and then, placed in a hybridization chamber (Corning Biosciences, Corning NY, USA) at 48°C for 48 h. Post-hybridization washes were done by placing the slides in a Copeland jar containing 1× SSC and 0.2% SDS at 48oC to gently remove the cover slip, followed by gentle agitation for 4 min. The slides were then transferred to another Copeland jar containing 0.1× SSC, 0.2% SDS at 25°C and agitated again for 4 min and subsequently transferred to 0.1× SSC and agitated for an additional 4 min. This wash was repeated once. Finally, the slides were dipped in 0.01× SSC and spun dry at 50 g for 2 min. The dried slides were scanned using an Axon 4000B scanner, and the resulting data was analyzed with GeneTraffic software (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). Lowess (Global) Normalization Method was utilized to normalize the ratio values. Genes with the mean of normalized log2 intensity ratio of ≥1 were identified as differentially expressed genes.

DNA sequence analysis

The identified differentially expressed genes were sequenced using an automated sequencer (ABI Prism 3100, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). These genes were then annotated by sequence similarity searches compared to the GenBank nonredundant (nr) protein database using the BLASTX program. cDNAs with BLASTX e-values ≤ 1e−10 were designated as having significant homology, and the higher score affirmed the corresponding gene. Functional categories of the identified genes were assigned based on the Gene Ontology annotations (http://www.geneontology.org/).

Real time RT-PCR

Real time RT-PCR analysis was employed to validate the relative change in expression of genes identified by microarray analysis. The RNA samples from TM-1 and CS-B22sh initially isolated for the microarray analysis were used for this analysis. Total RNA (2 μl) from each sample was treated with DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and used for cDNA synthesis. The first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with Oligo (dT) primer using RETROscript Reverse Transcription for RT-PCR Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). The cDNA was diluted with 1:5 for real time PCR reactions which were carried out in 384-well in the LightCycler 480 (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) using SYBR Green I Master dye (Roche Diagnostics). Gene-specific primers from the identified genes for real time RT-PCR were designed using Primer3 program (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi) based on the Blast consensus sequence from GenBank database for a specific cDNA. Each real time PCR reaction (20 μl) contained 8.2 μl of water, 0.4 μl of forward and reverse primers, respectively, 10 μl of 2× SYBR Green I Master, and 1 μl of the diluted cDNA. The amplification program consisted of 1 cycle of 95°C for 5 min for pre-incubation, followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 58°C for 10 s, and 72°C for 15 s. After amplification, a melting curve analysis was run using the program for one cycle at 95°C for 5 s, 65°C for 1 min, and 97°C with 0-s hold in the step acquisition mode, followed by cooling at 40°C for 10 s. A negative control without cDNA template was run with each analysis to evaluate the overall specificity. To normalize the total amount of cDNA in each reaction, the G. hirsutum alpha-tubulin 2 gene (Accession# AY345604) was co-amplified as the internal control. Each sample was replicated three times, and the resultant data were analyzed with the PCR efficiency correction using LightCycler 480 Relative Quantification Software (Roche Diagnostics Corporation) based on the relative standard curves describing the PCR efficiencies of the target and the reference gene.

Results and Discussion

SSH library, microarrays, and real time RT-PCR

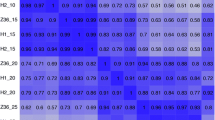

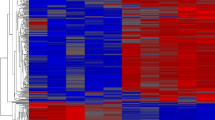

SSH cDNA fragments were obtained after two rounds of subtraction. The cDNA fragments ranged from about 300 bp to 1.3 kb with most fragment distributed between 400 and 800 bp (Fig. 1). The resulting SSH cDNA library contained about 3,480 clones. Four hundred and eighty clones were randomly picked from the SSH library for microarray analysis (Fig. 2), and 47 genes were identified as differentially expressed in CS-B22sh 15-dpa fiber when compared to TM-1. Blast analysis among these gene sequences showed that 36 genes were nonredundant/independent (Table 1). All of the 36 differentially expressed genes that were functionally annotated by the GenBank non-redundant protein database grouped into nine functional categories based on their putative functions. The functional classification showed that 33.4% of the identified genes were related to protein, nucleic acid, or lipid metabolisms, or their transport and/or signal transduction, 11.1% related to energy/carbohydrate metabolism; 8.3% related to cytoskeleton; 5.5% related to cellular structure and organization. The remaining genes were of unknown function (27.8%) or had no similarity with known accessions GenBank number protein database (13.9%) (Table 1). The microarray analysis data for the differentially expressed genes were further verified using real time RT-PCR. In some cases, a much higher-fold change was obtained from real time RT-PCR than that from microarray results (Fig. 3) This might be due to a low concentration of cDNA resulting in a relatively low dynamic range in microarrays (Ozturk et al. 2002). The overall results of real time RT-PCR agreed with the microarray data (Fig. 3).

Microarray screening for suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) cDNA library of CS-B22sh cotton fiber. A cDNA microarray was hybridized with fluorescent-labeled probe from CS-B22sh (red) and TM-1 (green) cotton fiber mRNA. Red color indicates relative overexpression in CS-B22sh cotton fiber and green color indicates relative overexpression in TM-1 cotton fiber. Yellow color indicates equal expression in both cotton fibers

SSH is a powerful technique to compare two populations of mRNA and obtain clones of genes that are expressed in one population but not in the other. The SSH technique requires only one subtractive hybridization round to remove the cDNAs common to both compared populations and thus, can achieve greater than 1,000-fold enrichment for differentially expressed cDNAs (Diatchenko et al. 1996). Ji et al. (2003) applied SSH, coupled with cDNA array, to isolate 172 genes significantly up-regulated in elongating cotton fiber. Using SSH, Zeng et al. (2006) identified 671 differentially expressed cDNAs in cotton somatic embryos, and more than one-third of these cDNAs were not reported in GenBank databases. Also, SSH greatly reduced the number of clones to be screened to a more manageable size, significantly reducing screening work and cost (Bernardo et al. 2007). In this study, we utilized combination of SSH, microarrays, and real time RT-PCR to identify 36 genes differentially expressed in CS-B22sh cotton 15-dpa fiber. Therefore, tandem of SSH, microarrays, and real time RT-PCR was an efficient and effective approach for identification of differentially expressed genes.

Genes related to cytoskeleton, cellular structure, and organization

Wilkins et al. (2005) found that the most highly expressed genes in developing fibers belong to the cytoskeleton gene family, and such gene family is responsible for directing polar elongation and, thus, contributes significantly to fiber shape. A previous study showed that significant numbers of cell wall and cell-wall-related genes were also highly expressed during cotton fiber expansion (Wilkins et al. 2005). In this study, we detected several genes involved in cytoskeleton, cellular structure, and organization that were differentially expressed in CS-B22sh 15-dpa cotton fiber compared to TM-1 fiber. These genes were two beta-tubulin (EF464665 and EF464668), and one gene each for actin (EF464673), putative kinesin light chain (EL738003), and cellulose synthase (CesA) (EF464675) (Table 1).

Kloth (1989) found that the level of tubulin protein increased approximately threefold in cotton fiber from 10 to 20 dpa, and reached a plateau or decreased slightly after 20 dpa, suggesting that the rapid rise in tubulin is correlated with the elongation of fiber and an increase in cellulose synthesis. Two alpha-tubulin and two beta-tubulin isotypes showed preferential accumulation in 10- and 20-dpa fibers, respectively, and this accumulation may be correlated with the dramatic changes in cortical microtubule arrays during cotton fiber development (Dixon et al. 1994). One gene encoding beta-tubulin had been isolated and characterized, which was differentially expressed in cotton fiber (Li et al. 2002). We, here, identified two beta-tubulin genes differentially expressed in CS-B22 15-dpa fiber compared to TM-1.

Tubulins are a major component of microtubules. Cortical microtubules are considered to provide spatial information to the organization of cellulose microfibrils in plant cells (Whittaker and Triplett 1999) Therefore, microtubulin arrays play a vital role in cell expansion by controlling the orientation of newly synthesized cellulose microfibrils (Reddy and Day 2000).

One of the differentially expressed genes we identified in CS-B22sh fiber was the actin gene. The actin cytoskeleton is necessary for cell elongation. RNA interference of cotton actin gene, GhACT1, disrupted actin cytoskeleton network in fibers and such inhibited fiber elongation (Li et al. 2005). Actin microfilament sometimes colocalize with cortical microtubules in cotton fibers (Andersland et al. 1998). The organization of cortical microtubules and some of the actin microfilaments parallels the orientation of cellulose microfibrils in cultured fiber cells (Seagull 1990). A cotton fiber kinesin may function in coordinating the interaction between actin microfilaments and microtubules during fiber growth and development (Preuss et al. 2004).

Cotton fiber consists mainly of cellulose which forms more than 90% of the harvested lint fiber. Cellulose synthase plays a vital role on cellulose synthesis. An important breakthrough in understanding cotton fiber and plant cell wall synthesis was the identification of the genes encoding cellulose synthase in cotton fiber using genomic methods (Pear et al. 1996). In this study, we found that a cellulose synthase gene (CesA) was differentially expressed in CS-B22sh 15-dpa cotton fiber by about threefold increase relatively to TM-1 cotton fiber (Table 1). Evidence showed that at least some of the CesA genes in plants encode a glycosyltransferase, and thus, are involved in the process of cellulose synthase (Delmer 1999). Mutation of the AtCesA-1 (Rsw1) gene in Arabidopsis resulted in significant decrease in cellulose deposition in young cells of seedlings (Arioli et al. 1998). AtCesA1, AtCesA3, and AtCesA6 are all required for primary wall cellulose biogenesis, whereas AtCesA4, AtCesA7, and AtCesA8 are all required for secondary wall cellulose biogenesis in xylem cells (Haigler et al. 2005).

Genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism

A number of genes associated with carbohydrate metabolism were differentially expressed in this CS-B22sh fiber. These genes include a glycosyl hydrolase family 3 protein (EL738002), a glycoside hydrolase family 5 (EL738010), and a GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase (EF464674) (Table 1). Ji et al. (2003) found that the mRNA level of wall-loosening enzyme genes, xylogucan endotransglycosylase (XET) and expansin, were about 100-fold higher in 10-dpa fiber cells compared to those in 0 dpa ovules, corresponding to their proposed role in cell enlargement. Expansin, XET, and EG act as wall loosening agents by loosening or cleaving bonds in the cell wall to allow cell expansion (Cosgrove 2000).

The genes encoding glycosyl and glycoside hydrolases were differentially expressed in CS-B22sh 15-dpa fiber compared to TM-1. Glycosyl hydrolases are a widespread group of enzymes that hydrolyze the glycosidic bond between two or more carbohydrates or between a carbohydrate and a non-carbohydrate moiety (Henrissat et al. 1995). Hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds is therefore crucial for energy uptake, cell wall expansion and degradation, turnover of signaling molecules (Davies and Henrissat 1995). Glycoside hydrolase family 5 is one of the largest glycoside hydrolase families, which contains primarily endo-acting enzymes that hydrolyze beta-mannans and beta-glucans (Dias et al. 2004). In plants, the enzymatic hydrolysis of glycosidic bond is particularly important for cell wall synthesis and expansion, starch metabolism, defense against pathogens, symbiosis, and signaling (Henrissat et al. 2001).

One of the genes we identified in this study was GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase (GMPase). GMPase catalyses the synthesis of GDP-D-mannose and represents the first committed step in the formation of all guanosin-containing sugar nucleotides found in plants which are precursors for cell wall biosynthesis and the synthesis of ascorbate (Keller et al. 1999). Guanosine-containing sugar nucleotides are formed by a set of reactions in which GDP-d-mannose is first synthesized from d-mannose-1-P by the action of GMPase and subsequently converted to other GDP-sugars. Antisense inhibition of the GMPase led to a significant reduction of the mannose content in leaf cell walls, indicating that GDP-d-mannose is the sole precursor for the incorporation of mannose into hemicellulose (Keller et al. 1999).

Genes associated with transport

An annexin (EL738017) and a dynamin-like protein (EL738016) genes functioning on transport were identified in CS-B22sh fiber. Annexins constitute a class of Ca2+-binding proteins that interact with phospholipid membranes in a Ca2+-dependent manner (Burgoyne and Geisow 1989). In plants, the first annexin-like proteins were identified from tomato (Boustead et al. 1989). Andrawis et al. (1993) first identified annexins in cotton fiber. They suggested these proteins might function on inhibition of beta-glucan (callose) synthase activity. Shin and Brown Jr. (1999) reported that the annexin gene was highly expressed in the elongation stages of cotton fiber differentiation, suggesting a role of this annexin in cell elongation. Annexins have diverse biological functions related to their Ca2+- and phospholipid-binding properties and are almost certainly involved in mediating some events in calcium-dependent regulation (Andrawis et al. 1993; Shin and Brown Jr. 1999).

Dynamin is one of the group members of high molecular weight proteins with GTPase activity (Obar et al. 1990). Dynamin and dynamin-related proteins are large GTP binding proteins that are involved in membrane trafficking (Kang et al. 2003). We here reported the identification of a dynamin-like protein in cotton fiber. A plant dynamin-like protein, ADL6, is involved in vesicle formation for vacuolar trafficking at the trans-Golgi network but not for trafficking to the plasma membrane in plant cell (Jin et al. 2001). Kang et al. (2003) identified two members of the Arabidopsis dynamin-related protein gene family, ADL1A and ADL1E, which are essential for polar cell expansion and cell plate biogenesis.

Association of differentially expressed genes with the short arm of chromosome 22

CS-B22sh is nearly isogenic to the TM-1 parent except that the pair of short arms of chromosome 22 of TM-1 is replaced with the pair of short arms of chromosome 22 of 3–79. Because of this unique genetic background, any difference associated between the parent TM-1 and CS-B22sh could putatively be attributed to the effect of substituted chromosome segments of 3–79 in CS-B22sh provided there is no residual effect of alien genome in other chromosomes after five backcrosses used in the development of CS-B22sh. Accordingly, comparative analysis of differentially expressed genes between TM-1 and CS-B22sh lines provided a tool to identify differentially expressed genes associated with the pair substituted short arm segments of chromosome 22 of 3–79 in CS-B22sh. However, some of the aneuploid lines originated in a different genetic background other than TM-1 and backcrossed to TM-1 to recover isogenic background of the aneuploid TM-1 parents used in developing CS-B lines. It is conceivable that some residual effect of original aneuploid parent or 3–79 genome in other chromosomes persisted despite of repeated backcrosses for several generations. This could slightly affects our results.

Previous studies demonstrated that CS-B22sh is associated with some important fiber traits including micronaire, fiber elongation, and strength (Jenkins et al. 2007; Saha et al. 2006; Saha et al. 2004). Knowledge of the biological important genes underlying these quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for these economically important fiber traits is very limited in cotton. The identification of candidate genes associated with the fibers of CS-B22sh can potentially accelerate the pace of discovering genes underlying the economically important complex fiber traits and candidate gene markers for use in marker-assisted selection program. This would expedite map based on cloning of important genes associated with complex fiber traits. This report represents our first attempt in identification of fiber-related genes in a cotton chromosomal substitution line, and further studies are needed to address more gene function-related issues such as direct assessments of functionality, measurement of transcript abundance of the differentially expressed genes at different stages of fiber development and exploitation of fiber cell expansion and cellulose biosynthesis.

References

Andersland JM, Dixon DC, Seagull RW, Triplett BA (1998) Isolation and characterization of cytoskeletons from cotton fiber cytoplasts. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant 34:173–180

Andrawis A, Solomon M, Delmer DP (1993) Cotton fiber annexins: a potential role in the regulation of callose synthase. Plant J 3:763–772

Arioli T, Peng L, Betzner AS, Burn J, Wittke W, Herth W, Camilleri C, Hofte H, Plazinski J, Birch R, Cork A, Glover J, Redmond J, Williamson RE (1998) Molecular analysis of cellulose biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Science 279:717–720

Basra A, Malik C (1984) Development of the cotton fiber. Intl. Rev Cytol 89:65–113

Bernardo A, Bai G, Guo P, Xiao K, Arron C, Guenzi AC, Ayoubi P (2007) Fusarium graminearum-induced changes in gene expression between Fusarium head blight-resistant and susceptible wheat cultivars. Funct Integr Genomics 7:69–77

Boustead CM, Smallwood M, Small H, Bowles DJ, Walker JH (1989) Identification of Ca2+-dependent phospholipid-binding proteins in higher plant cells. FEBS Lett 244:456–460

Burgoyne RD, Geisow MJ (1989) The annexin family of calcium-binding proteins. Cell Calcium 10:1–10

Cosgrove DJ (2000) Expansive growth of plant cell walls. Plant Physiol Biochem 38:109–124

Diatchenko L, Lau Y-FC, Campbell AP, Chenchik A, Mooadam F, Huang B, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov K, Gurskaya N, Sverdlov ED, Siebert PD (1996) Suppression subtractive hybridization: a method for generating differentially regulated or tissue-specific cDNA probes and libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:6025–6030

Dias FMV, Vincent F, Pell G, Prates JAM, Centeno MSJ, Tailford LE, Ferreira LMA, Fontes CMGA, Davies GJD, Gilbert HJ (2004) Insights into the molecular determinants of substrate specificity in glycoside hydrolase family 5 revealed by the crystal structure and kinetics of Cellvibrio mixtus mannosidase 5A. J Biol Chem 279:25517–25526

Davies G, Henrissat B (1995) Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases. Structure 3:853–859

Delmer DP (1999) Cellulose synthesis: exciting times for a difficult field. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol 50:245–276

Dixon DC, Seagull RW, Triplett DA (1994) Changes in the accumulation of [alpha]- and [beta]-tubulin isotypes during cotton fiber development. Plant Physiol 105:1347–1353

Frelichowski JE Jr, Palmer MB, Main D, Tomkins JP, Cantrell RG, Stelly DM, Yu J, Kohel RJ, Ulloa M (2006) Cotton genome mapping with new microsatellites from Acala ‘Maxxa’ BAC-ends. Mol Gen Genomics 275:479–491

Guo W, Cai C, Wang C, Han Z, Song X, Wang K, Niu X, Wang C, Lu K, Shi B, Zhang T (2007) A microsatellite-based, gene-rich linkage map reveals genome structure, function and evolution in Gossypium. Genetics 176:527–541

Haigler CH, Zhang D, Wilkerson CG (2005) Biotechnological improvement of cotton fiber maturity. Physiol Plant 124:285–294

Han ZG, Guo WZ, Song XL, Zhang TZ (2004) Genetic mapping of EST-derived microsatellites from the diploid Gossypium aboreum in allotetraploid cotton. Mol Gen Genomics 272:308–327

Han Z, Wang C, Song X, Guo W, Guo J, Li C, Chen X, Zhang T (2006) Characteristics, development and mapping of Gossypium hirsutum derived EST-SSRs in allotetraploid cotton. Theor Appl Genet 112:430–439

Hedrick S, Cohen DI, Nielsen EA, Davis MM (1984) Isolation of cDNA clones encoding T cell-specific membrane-associated proteins. Nature 308:149–153

Henrissat B, Callebaut I, Fabrega S, Lehn P, Mornon JP, Davies G (1995) Conserved catalytic machinery and the prediction of a common fold for several families of glycosyl hydrolases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92:7090–7094

Henrissat B, Coutinho PM, Davies GJ (2001) A census of carbohydrate enzymes in the genome of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 47:55–72

Jenkins JN, Wu J, McCarty JC, Saha S, Gutierrez OA, Hayes R, Stelly DM (2007) Genetic effects of thirteen Gossypium barbadense L. chromosome substitution lines in topcrosses with Upland cotton cultivars: II fiber quality traits. Crop Sci 47:561–570

Jin JB, Kim YA, Kim SJ, Lee SH, Kim DH, Cheong G-C, Hwang I (2001) A new dynamin-like protein, ADL6, is involved in trafficking from the trans-Golgi network to the central vacuole in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 13:1511–1525

Ji SJ, Lu YC, Feng JX, Wei G, Li J, Shi YH, Fu Q, Liu D, Luo JC, Zhu YX (2003) Isolation and analyses of genes preferentially expressed during early cotton fiber development by subtractive PCR and cDNA array. Nucleic Acids Res 31:2534–2543

Kang B-H, Busse JS, Bednarek SY (2003) Members of the Arabidopsis dynamin-like gene family, ADL1, are essential for plant cytokinesis and polarized cell growth. Plant Cell 15:899–913

Karaca MS, Saha JN, Jenkins A, Zipf RJ, Kohel RJ, Stelly MD (2002) Simple sequence Repeat (SSR) markers Linked to the ligon lintless (Li) mutant in cotton. J Hered 93:221–224

Keller R, Renz FS, Kossmann J (1999) Antisense inhibition of the GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase reduces the ascorbate content in transgenic plants leading to developmental changes during senescence. Plant J 19:131–141

Kim HJ, Triplett BA (2001) Cotton fiber growth in planta and in vitro. models for plant cell elongation and cell wall biogenesis. Plant Physiol 127:1361–1366

Kloth RH (1989) Changes in the level of tubulin subunits during development of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) fiber. Physiol. Plant 76:37–41

Lacape JM, Nguyen TB, Courtois B, Belot JL, Giband M, Gourlot JP, Gawryziak G, Roques S, Hau B (2005) QTL analysis of cotton fiber quality using multiple Gossypium hirsutum x Gossypium barbadense backcross generations. Crop Sci 45:123–140

Li X-B, Cai L, Cheng N-H, Liu J-W (2002) Molecular characterization of the cotton GhTUB1 gene that is preferentially expressed in fiber. Plant Physiol 103:666–674

Li X-B, Fan X-P, Wang X-L, Cai L, Yang W-C (2005) The cotton ACTIN1 gene is functionally expressed in fibers and participates in fiber elongation. The Plant Cell 17:859–875

Liang P, Pardee AB (1992) Differential display of eukaryotic messenger RNA by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Science 257:967–971

Lisitsyn N, Lisitsyn N, Wigler M (1993) Cloning and differences between two complex genomes. Science 259:946–951

Meredith R (2000) Continued progress for breeding for yield in the USA? In: Kechagia U (ed) Proceedings of the World Cotton Research Conference II. Athens, Greece, pp 97–101

National Cotton Council (2005) http://www.cotton.org. Cited 15 June 2007

Nguyen TB, Giband M, Brottier P, Risterucci AM, Lacape JM (2004) Wide coverage of the tetraploid cotton genome using newly developed microsatellite markers. Theor Appl Genet 109:167–176

Obar RA, Collins CA, Hammarback JA, Shpetner HS, Vallee RB (1990) Molecular cloning of the microtubule-associated mechanochemical enzyme dynamin reveals homology with a new family of GTP-binding proteins. Nature 347(6290):256–261

Ozturk ZN, Talame V, Deyholos M, Michalowski CB, Galbaith DW, Gozukirmisi N, Tuberosa R Bonert HJ (2002) Monitoring large-scale changes in transcript abundance in drought and salt-stressed barley. Plant Mol Biol 48:551–573

Park YH, Alabady MS, Ulloa M, Sickler B, Wilkins TA, Yu J, Stelly DM, Kohel RJ, El-Shihy OM, Cantrell RG (2005) Genetic mapping of new cotton fiber loci using EST-derived microsatellites in an interspecific recombinant inbred line cotton population. Mol Gen Genomics 274:428–441

Pear JR, Kawagoe Y, Schreckengost WE, Delmer DP, Stalker DM (1996) Higher plants contain homologs of the bacterial celA genes encoding the catalytic subunit of cellulose synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:12637–12642

Preuss ML, David R, Kovar DR, Lee Y-RJ, Staiger CJ, Delmer DP, Liu B (2004) A plant-specific kinesin binds to actin microfilaments and interacts with cortical microtubules in cotton fibers. Plant Physiol 136:3945–3955

Reddy ASN, Day IS (2000) The role of the cytoskeleton and a molecular motor in trichome morphogenesis. Trends Plant Sci 5:503–505

Rong J, Pierce GJ, Waghmare VN, Rogers CJ, Desai A, Chee PW, May OL, Gannaway JR, Wendel JF, Wilkins TA, Paterson AH (2005) Genetic mapping and comparative analysis of seven mutants related to seed fiber development. Theor Appl Genet 111:1137–1146

Saha S, Wu J, Jenkins JN, McCarty JC Jr, Gutierrez OA, Stelly DM, Percy RG, Raska DA (2004) Effect of chromosome substitutions from Gossypium barbadense L. 3–79 into G. hirsutum L. TM-1 on agronomic and fiber traits. J Cotton Sci 8:162–169

Saha S, Jenkins JN, Wu J, McCarty JC, Gutierrez OA, Percy RG, Cantrell RG, Stelly DM (2006) Effect of chromosome specific introgression in Upland cotton on fiber and agronomic traits. Genetics 172:1927–1938

Seagull RW (1990) The effects of microtubule and microfilament disrupting agents on cytoskeletal arrays and wall deposition in developing cotton fibers. Protoplasma 159:44–59

Shin H, Brown RM Jr (1999) GTPase activity and biochemical characterization of a recombinant cotton fiber annexin. Plant Physiol 119:925–934

Song X, Wang K, Guo W, Zhang J, Zhang T (2005) A comparison of genetic maps constructed from haploid and BC1 mapping populations from the same crossing between Gossypium hirsutum L. and Gossypium barbadense L. Genome 48:378–390

Stelly DM, Saha S, Raska DA, Jenkins JN, McCarty JC, Gutierrez AO (2005) Registration of 17 Upland (Gossypium hirsutum) germplasm lines disomic for different G. barbadense chromosome or arm substitutions. Crop Sci 45:2663–2665

Tedder TF, Streuli M, Schlossman SF, Saito H (1988) Isolation and structure of a cDNA encoding the B1 (CD20) cell-surface antigen of human B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:208–212

Tomkins J, Peterson D, Yang T, Main D, Wilkins T, Paterson A, Wing R (2001) Development of genomic resources for cotton (Gossypium hirsutum); BAC library construction, preliminary STC analysis, and identification of clones with fiber development. Mol Breeding 8:255–261

Wan CY, Wilkins TA (1994) A modified hot borate method significantly enhances the yield of high-quality RNA from cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Anal Biochem 223:7–12

Wilkins TA, Jernstedt JA (1999) Molecular genetics of developing cotton fibers. In: Basra AS (ed) Cotton fibers. The Haworth, Binghamton, NY, USA, pp 231–269

Wilkins T, Arpat A, Sickler B (2005) Cotton fiber genomics: Developmental mechanisms. Pflanzenschutz-Nachrichten Bayer 58:119–139

Whittaker DJ, Triplett BA (1999) Gene-specific changes in α-tubulin transcript accumulation in developing cotton fibers. Plant Physiol 121:181–188

Wu Z, Soliman KM, Zipf A, Saha S, Sharma GC, Jenkins JN (2005) Isolation and characterization of genes differentially expressed in fiber of Gossypium barbadense L. J of Cotton Sci 9:166–174

Velculescu VE, Zhang L, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW (1995) Serial analysis of gene expression. Science 270:484–487

Zeng F, Zhang X, Zhu L, Tu L, Xiaoping Guo X, Nie Y (2006) Isolation and characterization of genes associated to cotton somatic embryogenesis by suppression subtractive hybridization and macroarray. Plant Mol Biol 60:167–183

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to recognize the late Dr. Allan E. Zipf’s suggestions when writing the proposal for this project. We also thank Dr. Govind C. Sharma for his valuable suggestions when composing this manuscript. This research was a collaborative effort by the Agricultural Experiment Station, Alabama A&M University, and USDA-ARS Crop Science Research Lab scientists. We thank Dr. Michael Crowley, Genomics Core Facility at University of Alabama at Birmingham, for his assistance on microarray analysis in this project. We acknowledge the contribution of Dr. D.M. Stelly, Texas A&M University for developing CS-B22sh line. Contributed by the Agricultural Experiment Station, Alabama A&M University, Journal No. 615. This research was supported in part by the United States Department of Agriculture—Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service (USDA-CSREES) Capacity Building Grant#2003-38814-13932.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper is dedicated to the memory of the late Dr. Allan Zipf. Mention of trademark or proprietary product does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of the product by the United States Department of Agriculture or Alabama A&M University and does not imply its approval to the exclusion of other products that may also be suitable.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Z., Soliman, K.M., Bolton, J.J. et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes associated with cotton fiber development in a chromosomal substitution line (CS-B22sh). Funct Integr Genomics 8, 165–174 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-007-0064-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-007-0064-5