Abstract

Food production and consumption is one of the major causes of global environmental degradation. One way to address environmental impacts in the food and beverage (F&B) sector is via the adoption of environmental management systems (EMS). To date, EMS research has focused predominantly on countries and sectors based in the Global North despite growing recognition of the global extent of environmental impacts from food production and consumption. In order to widen our knowledge of this topic in an under-researched emerging economy, this study examined factors determining EMS adoption within the Malaysian F&B industry. Drawn from a survey of 42 companies, this research investigated the drivers, barriers, and incentives to the adoption of the internationally recognized standard, ISO 14001. Discrepancies between the perceptions of small- and medium-sized enterprises and large companies’ as well as different product market groups were observed. It was found that large companies tend to have better understanding of the EMS concept and the enhancement of company image and improvement of environmental performance were the main drivers to implement EMS. High implementation costs and the lack of knowledge on the ISO 14001 standard were identified as the primary barriers to EMS adoption. Tax relief for certified companies and training and capacity building were considered as the most important incentives. Strategies were proposed to improve the environmental performance of Malaysian F&B companies which can strengthen the competitiveness of Malaysian F&B products in the global food market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Food production and consumption is one of the major causes of global environmental degradation (Garnett 2008). Impacts include irreversible land use change for crop cultivation, air, land and water pollution from food processing, and escalating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from within the food supply chain and the decomposition of organic waste. (Papargyropoulou et al. 2014). Consumers of food are increasingly demanding more varied and seasonal food products, which in turn have increased the complexity of global food supply chains (Padfield et al. 2012). Despite the growing interest in food waste minimization initiatives, it is common practice for edible food waste to be disposed of to landfill (Papargyropoulou et al. 2016). The anaerobic digestion of food waste in landfill produces methane that is twenty-one times more potent than carbon dioxide. Considering the exponential growth of the human population, it is expected that GHG emissions from food production and consumption will continue to increase (Searchinger et al. 2013).

The concept of sustainable consumption and production (SCP) aims to reduce society’s ecological footprint whilst maintaining economic prosperity (Bentley 2008). The concept rests on the ideals of cleaner production, waste and pollution prevention, eco-efficiency, and green productivity. Sustainable consumption promotes an efficient allocation of resources in the entire supply chain. SCP embraces life-cycle perspectives in order to improve organizational environmental performance throughout the value chain (UNEP 2012). Environmental management systems (EMS) are one way to achieve SCP as it provides an organization with a framework to mitigate impacts to ecological footprints. The framework is based on a continuous improvement cycle incorporating the ‘plan-do-check-act principle’ to improve environmental performance. The standard specifies requirements to ensure that an organization meets their environmental objectives through a consistent control of operations (Massoud et al. 2010).

The most well-known standard for EMS is the International Organization Standardization (ISO) 14001 (Jones et al. 2012). The standard was developed by ISO in 1996 and mandates the adopter to establish environmental policy, planning, implementation, checking and corrective actions, as well as management review (Nishitani 2010). The benefits of adopting ISO 14001 certification include improvements to both organizational and environmental performance. The standard has become more prevalent in the trade of international F&B products, especially as a means to gain access to environmentally conscious market such as Europe, Japan, and USA (Nishitani 2010). Studies have highlighted the positive effect of ISO 14001 standard on the export performance (Bellesi et al. 2005). The importance of the EMS standard is mainly in response to customer requirement for green products (Turk 2009). EMS allows companies to create a differentiation of products in the marketplace and to ensure third-party guarantees over a company’s environmental performance (Nishitani 2010).

Less positively, it has been reported that an EMS standard has the potential to marginalize companies (Neumayer and Perkins 2004) leading to a clear divide between those companies that can meet the environmental certification requirements of specific sectors and countries and those that cannot. This is reflected in the uneven global adoption of the ISO 14001 standard which has seen an exponential rise in certifications in the Global North (e.g. Europe [37.5%]) and comparatively fewer adoptions in the Global South [e.g. Southeast Asia (3.5%), Africa (0.9%), Middle East (1.4%), Central and South America (3.1%)] (ISO 2016). The exception is China which tops the global list of countries with companies achieving the ISO 14001 standard (ISO 2016).

Similarly, the majority of past EMS studies focus on countries in the Global North, such as those in Europe and USA (Salim et al. 2017). Few contributions have been made to offer holistic perspectives on the identification of drivers, barriers, and the potential pathways to overcome the barriers (Boiral et al. 2017). Researchers have tended to exclude small and medium enterprises (SMEs) from their analysis of case studies in developing countries. Tackling SMEs is particularly problematic considering the sheer number of companies and the difficulties in coordinating activities for such businesses that typically operate on relatively slim profit margins (Lewis et al. 2015). Few studies have examined the impacts of supply chain exclusivity of EMS standards (Neumayer and Perkins 2004).

In order to widen our knowledge of this topic in an under-researched country in the Global South, this study examined factors determining EMS adoption within the Malaysian F&B industry. It is reported that food and beverage (F&B) products share approximately 10% of the country’s manufacturing output (AHK Malaysia 2012) making it a salient case study for investigation. Food waste in Malaysia remains a major challenge, where food waste makes up the largest proportion (45%) of the total solid waste generation (NSWMD 2013). As in the case with many countries in the Global South, a significant amount of food waste is generated on both the production and consumption side (Papargyropoulou et al. 2014). In Malaysia, the situation is likely to change following the Prime Minister’s ambitious commitment to reduce the country’s environmental footprint at the 2009 Climate Summit in Copenhagen (Manzo and Padfield 2016). Despite Malaysia’s status as one of the largest GHG emitters in Southeast Asia, few companies in the F&B sector have implemented the EMS standard, where it accounts for only 6% of the total ISO 14001 adoptions in Malaysia (ISO 2016). Identifying the drivers, barriers, and appropriate incentives is an important step in formulating a systematic plan for the adoption of EMS in the Malaysian F&B sector, which in turn can support improved competitiveness and inclusivity of Malaysian F&B products in global food markets.

Research methodology

Data collection

The flow of research methods applied in this study is presented in Fig. 1. Three approaches to data collection were applied: (i) a desk-based study; (ii) direct site visits; and (iii) a questionnaire survey.

The desk-based study was employed to review previous research, to investigate current Malaysian environmental policy and practices, and to research the context of the Malaysian F&B sector. Government reports are widely available through the corresponding governmental departments such as Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, SME Corporation Malaysia, and Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM). A desk-based study was also performed to analyse European import data from Malaysia from European Commission (2017), the EMS adoption trend from ISO (2016), and the overall export of Malaysia from DOSM (2017). Due to the unavailability of sector-specific trends of the standard, the depicted figures cover all industry sectors certification density. Europe was chosen in this study because it has pioneered a range of sustainability policy initiatives, including policies for food products (European Commission 2008). These data are used to observe the negative influence of the increasing importance of EMS standard on Malaysian imports to Europe.

A bilingual (English and Chinese) questionnaire was designed which covered three areas of enquiry: drivers, barriers, and incentives to implement EMS. The respondents were asked to identify the three most important drivers, barriers, and incentives. The general company information (e.g. firm size, commodity type, product markets, and type of certifications) and the perception towards EMS were also drawn from the respondents (e.g. environmental awareness, future adoption of EMS standards, and knowledge on ISO 14001).

The companies selected for the case study were chosen based on two factors: the company should be a Malaysian F&B company and its product(s) manufactured within Malaysia. Once the companies had been identified, the questionnaire was undertaken via one of the following methods: an electronic survey, telephone survey, an on-site visit and survey, or during an industry product conference. The owner, managers, or the decision-makers of the companies were targeted for questioning since it was assumed individuals in positions of authority would be best placed to respond to questions (Lewis et al. 2015). The on-site visits and surveys were particularly useful as they allowed for face-to-face interviews and the opportunity to observe the place of work. Questionnaires sent via e-mail were generally less effective in terms of response rate (Studer et al. 2006) but useful to reach companies in remote locations.

Sample and company description

Following a successful pilot study performed by undertaking site visits and survey questionnaire, a total of 42 F&B companies successfully completed the questionnaire. The sample size is consistent with previous studies in developing countries, i.e. Brazil (Campos 2012), Lebanon (Massoud et al. 2010), and Malaysia (Tan 2005) where the sample size ranged from between 18 and 45 companies. Table 1 describes the firm size and product markets of the surveyed companies. It was found that 34 companies (81%) were identified as SMEs, whilst eight others (19%) were large companies. In terms of product markets, most F&B companies focus on local market (43%), whereas exporting companies to regional (Asia) and international markets share an equal distribution (28%). The majority of the surveyed companies were located in the F&B manufacturing states of Malaysia: Selangor (43%) and Kuala Lumpur (26%) and followed by Johor (12%), Sarawak (7%), Pulau Pinang (5%), and other states (7%).

In terms of sub-sector, beverage and alcohol (29%) and confectionaries (26%) companies comprised of the largest proportion. This was followed by sauces (14%), salts, herbs and spices (10%). The least studied sector is oil and fats and vegetable products with an equal number (2%). This distribution is relatively consistent with the overall F&B company profile in Malaysia where it comprises a large number of beverage processing, fish and meat products, confectionaries, and vegetable products (MIDA 2013).

In terms of business certifications, 67% of the companies surveyed had Halal certification. The number is followed by the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) (57%) and an equal number of ISO 9001 and ISO 22001 certifications (29%). Only two companies (4%) had obtained ISO 14001 that is likely to reflect the low levels of environmental certification within the Malaysia F&B industry as a whole. As discussed below, the ISO 14001 standard has not gained importance for local market entry at present. Figure 2 depicts the number of certifications as categorized by F&B sub-sector.

Data management and analysis

The data collected from the survey process were numerically coded using the SPSS Statistical Software. Drivers, barriers, and incentives were coded as binary data (i.e. either a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response), whereas attitude, perceptions towards EMS, and company characteristics were coded as categorical data (Massoud et al. 2010). The first approach involves descriptive statistics of the firm-level characteristics (firm size, products market, and certifications). The second part presents the distribution of the perceived drivers, barriers, and incentives. The descriptive result of the temporal distribution of European imports from Malaysia and ISO 14001 certifications trend was presented to examine the supply chain exclusivity.

The difference between company sizeFootnote 1 and product markets was analysed using the two-way MANOVA (Prajogo and McDermott 2014). The dependent variables used in the study include the environmental initiatives as well as the drivers, barriers, and incentives. The F-value and P value of Wilks’ lambda indicator in the ‘Tests of Between-Subjects Effects’ were used to determine the statistical significance of the correlation. Wilks’ lambda is the most widely used indicator in quantitative research (Todorov and Filzmoser 2010). The limit for statistical significance to assess the correlation is P < 0.1. The ‘Estimated Marginal Means’ was used to identify the mean discrepancy between each independent variables group (e.g. differences between SMEs and large companies).

Analysis and findings

Environmental initiatives

The survey revealed that most F&B companies (98%) recognized the importance of mitigating on-site environmental impacts (e.g. effluent discharge, air pollution, waste disposal) which implies that they have a high environmental awareness. However, only seven companies (17%) had a good level of understanding of the EMS concept. Approximately 17% of the companies had limited knowledge of EMS, whilst 14 companies (33%) were completely unfamiliar with the concept. The two-way MANOVA result suggests that large companies tend to display a greater understanding on the concept (P < 0.05). In terms of their intention to adopt EMS, only 55% of the companies were interested to adopt the ISO 14001 certification and 14% were unsure whether they would adopt the standard in the future.

Drivers, barriers and incentives

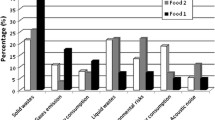

Figure 3 depicts the perceived drivers for EMS adoptions. This study found that the key drivers were to enhance company image (62%) and to improve environmental performance (60%). Other drivers such as following international industry trends (38%), reduce operational costs (36%), and meeting customers demand (33%) were reported as relatively important factors. The enhancement of company image and reduction in operational costs were salient drivers for large companies (P < 0.1), whereas use as a marketing tool was highly regarded by SMEs (P < 0.1). Product markets were also reported as a significant determinant for operational cost saving driver, where companies targeting local and regional markets regarded it as an important driver (P < 0.01). Use as a marketing tool (26%), overcome export barrier (19%), and meeting company requirements (14%) were the least important barriers.

Figure 4 reports Malaysian F&B companies’ barriers to implement EMS standards. High certification costs (57%), lack of in-house knowledge (50%), and the lack of government support and incentives (48%) were perceived as the most salient barriers for Malaysian F&B companies to implement EMS. Other factors such as not a legal requirement (31%), unclear benefits (31%), and no customers demand (29%) were perceived as relatively significant barriers which hinder EMS adoption. Product markets were found to be a predictor of the non-existence of legal requirements to adopt EMS standard (P < 0.05). The least recognized barriers were time demand (19%), not required for export (14%), and not a CEO priority (12%).

This study revealed that the most important incentive is tax relief (64%). This is consistent with research by Studer et al. (2008) who found that stakeholders perceived financial incentives to be more effective to reduce the barriers to implement EMS. Malaysian F&B companies recognized the importance to develop their knowledge and capability before the implementation of EMS, where training and capacity building (62%) and enhanced knowledge on ISO 14001 standards (52%) were regarded as important incentives. The measures with the least incentives were the provision of soft loans (26%), public–private partnership (27%), and the establishment of a national institute (10%). Figure 5 depicts the most important incentives to increase the adoption of EMS amongst Malaysian F&B companies.

Discussion

The majority of the companies surveyed in this research recognize the importance of EMS to reduce their environmental impacts and the potential benefits to their corporate image. Companies recognized less the financial savings of EMS since only 13% perceived there to be potential in reducing operational costs. This implies a lack of knowledge in terms of the cost saving potential of EMS but also the lack of demand in efforts to save costs in terms of raw materials, water and waste reduction (McKeiver and Gadenne 2005). This finding is perhaps unsurprising considering the highly subsidized economy of Malaysia that acts as a disincentive to companies in reducing wastage and improving production efficiency (Papargyropoulou et al. 2012). This position may change in time as the cost of living becomes more expensive and government subsidies are removed on key commodities.

The study also found that the motivation to improve corporate environmental performance is a significant driver to implement the ISO 14001 standard. This finding is consistent with a study by Fryxell and Szeto (2002) who found that the improvement of environmental performance was perceived as an important driver. This indicates a strong internal motivation from Malaysian F&B companies to acquire EMS than the external ones. Furthermore, consistent with research by Brammer et al. (2012) environmental awareness was higher amongst larger Malaysian F&B companies as compared with SMEs.

Notwithstanding the high environmental awareness displayed, there is a low intention to adopt the EMS standard. This finding is likely associated with the low engagement and support from industry associations and related government agencies to promote environmental certifications as a way to reduce cost and gain access to international markets. According to KPMG (1997), the absence of a competent body and accredited verifiers in Malaysia and the lack of clarity on the potential benefit of EMS have been the major challenge for the F&B sector to implement EMS standards. With improved knowledge on the benefits of EMS, especially in terms of the economic savings, adoption rates are likely to increase in the future.

This study did not confirm a previous study by McKeiver and Gadenne (2005) where customers demand was reported as a strong driver. This is likely attributed to the weak environmental awareness amongst domestic customers and thus the limited preference towards green products (Goh and Wahid 2015). Fostering local public knowledge on environmental awareness and sustainable consumption patterns is, therefore, an important task in order to create stronger external pressure towards F&B companies to adopt voluntary EMS standards (Papargyropoulou et al. 2012).

Inconsistent with the findings of a study examining environmental management systems in the Chinese manufacturing sector (Zeng et al. 2005), overcoming export barriers is perceived as a weak driver to implement EMS in the Malaysian F&B industry. In the future, this could become an important driver for Malaysian companies, especially if efforts are made by industry and governmental bodies to develop businesses beyond national and regional markets (Qi et al. 2011). An indirect way of improving the rate and number of companies adopting EMS in Malaysia is via international market penetration. International markets, notably those in Europe, Japan, and North America, generally require companies to meet more stringent food standards, such as high levels of environmental performance (Nishitani 2010). It should be noted that increasing the export of F&B products to the international markets to improve environmental performance does raise questions over the potential increase in GHG emissions from cross-country transportation (Liu et al. 2016).

The high aggregate investment values for certification such as registration fees, auditing costs, and any other related costs may go beyond the SMEs’ financial capability, especially in the Global South (Staniškis et al. 2012). SMEs, in particular, are profit-oriented and focus on short-term financial goals (Lewis et al. 2015). The argument is consistent with the finding of this study where SMEs tend to perceive costs saving as their main driver to implement EMS. According to an estimate by the Global Environmental and Technology Foundation, the cost for ISO 14001 is between USD 24,000 and USD 128,000 per site (dependent on company size), with an annual maintenance cost between USD 5000 to USD 10,000 (Jiang and Bansal 2003). Such a high cost almost certainly excludes the majority of SMEs from participating within the scheme.

The limited government engagement and training for F&B companies is likely to have contributed towards the lack of knowledge to manage environmental impacts. This issue also points towards the unavailability of environmental education and technical assistances (technological infrastructures, information system, regulatory enforcement, etc.) from government and industry bodies for environmental management. In Hong Kong (Studer et al. 2006) and New Zealand (Lewis et al. 2015), research indicates that a lack of knowledge was a less salient barrier to EMS adoption. Although it was reported that government have a significant role in shaping corporate environmental responsibility, such as coercive and normative powers (Delmas and Toffel 2004), the Malaysian government can play a more significant role by developing further the current environmental regulatory instruments and technological infrastructure.

The relationship between the barriers and the incentives points towards the need for improving company and public awareness on the potential benefits from adopting EMS (Papargyropoulou et al. 2012). Developed countries tend to have well-established environmental regulations and incentives, notably high stringency of regulatory enforcement, availability of financial incentives, and wide accessibility of information regarding EMS, which in turn results in widespread adoption of ISO 14001 standards (Neumayer and Perkins 2004). For instance, Hong Kong provides both monetary and non-monetary incentives such as tax deduction, award schemes, eco-labelling, technical guidance, financial assistance, and affordable consultancy fees (Steger 2000). The Singaporean government also promotes subsidies for EMS certification and consultancy services costs for up to 70% through the Capacity Development Grant as well as providing tax deduction for certified companies, especially SMEs (Quazi et al. 2001).

ISO 14001 and supply chain exclusivity

As introduced earlier, the adoption of the ISO 14001 standard has not been globally homogenous (ISO 2016). In countries where there is legislation to achieve an EMS standard, coercive pressures are exerted to their suppliers to adopt a specific environmental standard (Arimura et al. 2011). This type of policy protects customers against unethical and unsustainable behaviour of focal companies’ upstream partners (Gualandris et al. 2015).

Prakash and Potoski (2006) argued that for environmentally conscious markets (e.g. Europe, Japan, USA) where adoption of ISO 14001 standards is widespread, it commonly consists of domestic customers with a high demand on green products (Bellesi et al. 2005). From a broader economic perspective, environmentally conscious markets chose to reduce trade with polluting firms in a way to reduce the imported negative externalities due to the low goods price and quality (Ludema and Wooton 1994). The adoption of EMS standard can be one way for a company in developing countries to increase the visibility of their environmental responsibilities to discerning foreign customers in order to satisfy their demand but also to gain entry to a fair competition in a free-market economy (Bellesi et al. 2005).

In order to analyse supply chain exclusivity within the context of the Malaysian F&B sector, comparative figures between the import ratio from Malaysia to Europe and Japan (Figs. 6, 7) and the ISO 14001 density in the countries are presented (Fig. 8). It is apparent from the figures that European food and beverage import from Malaysia have experienced a steep decline alongside an increase in the number of ISO 14001 certifications in Europe, whilst the growth rate and the number of ISO 14001 in Malaysia remain poorly represented. Europe’s total import from Malaysia also experienced a downward trend after 2000. Although in terms of Malaysian export value there is an upward trend, the ratio of exportFootnote 2 over GDP has declined in the past decade which implies that the role of overall export in Malaysia is decreasing (Fig. 8).

Europe food and beverage import from Malaysia (European Commission 2017)

Malaysia export value and ratio to all countries (DOSM 2017)

The exclusion of Malaysian F&B products from the European market could continue if the global demand towards green products increases. This issue creates a divide between multinational companies who can afford to certify with ISO 14001 standards and SMEs who do not have the capacity to do so. This study found that the two multinational companies studied are certified with ISO 14001 standards and export their goods to environmentally conscious markets. On the contrary, uncertified F&B SMEs can only gain entry to local and Asian markets because of their inability to obtain the necessary instrument to overcome environmental trade barriers.

It is argued that if Malaysia continues along the same trend, economic losses may occur in either the context of market losses or the natural capital depletion which is fuelled by unsustainable consumption and climate change. Moving Malaysia towards a widespread adoption of EMS standards not only prevents internal environmental and economic damages but also helps boost the economy by attracting countries seeking investments tied to environmental performance (OECD 2014).

Future steps for EMS adoption in Malaysia

The findings from this study suggest there is an important role to play for government, F&B industry bodies, and educational institutions in promoting the adoption of EMS to the industry and public as a whole. A strategy to promote EMS adoption could take the form of mandatory EMS requirements through legislation (Nikolaou et al. 2012) and to encourage voluntary adoption supported by capacity building exercises via financial as well as technical incentives (Zeng et al. 2005). This initiative could support improved inclusivity of Malaysian F&B products in the global food market (Neumayer and Perkins 2004).

Likewise, balancing incentives with financial disincentives could also encourage the adoption of EMS (Majumdar and Marcus 2001). For example, the removal of subsidies (Papargyropoulou et al. 2012) and carbon pricing (Fan et al. 2014) will enable government agencies to allocate more finance towards environmental causes. Finance could also be directed to natural resource conservation, recycling activities, and a shift into renewable energy amongst Malaysian F&B companies.

Developing a national standard on EMS also offers an affordable alternative to the expensive and extensive documentation required for the ISO 14001 standard, especially for SMEs. The development should be in accordance with the framework of ISO 14001 standards for its global recognition, e.g. Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) in Europe and Eco-Action 21 (2017) in Japan. The establishment of a Malaysian national EMS standard is important owing to the fact that 80% of F&B companies in the country are SMEs which commonly have poor financial capacity to adopt international standards.

Establishing a national strategy is also an approach to facilitate a transition towards SCP. To date, the Malaysian government has established twenty-two SCP policies and these are embedded within the 10th Malaysia Plan, Government Transformation Programme, and Economic Transformation Programme (Adham et al. 2013). However, implementation is obstructed by weak regulatory enforcement, outdated policy instruments, and limited allocation of financial resources. Enhancing the current regulations, more stringent enforcement and the development of F&B industry-related strategies will help to increase the priority of the environment for both companies and customers. In a recent study of GHG trends within the Malaysian F&B industry, a sector-specific strategy (in this case sustainable food systems strategy) was recommended for a more integrated and sustainable F&B sector (Padfield et al. 2012).

There is also a clear need to advance the public’s environmental awareness in order to create a demand-driven EMS adoption within the Malaysian F&B industry (Massoud et al. 2010). Educating citizens will drive change to the cultural value, attitudes, and behaviours of customers (Lee et al. 2016), thereby enabling sustainable consumption which will exert more localized demand for green products (Adham et al. 2013).

Conclusion

This paper investigated the drivers, barriers, and incentives for Malaysian F&B companies to implement the ISO 14001 standard. Drawn from a sample of companies based predominantly in the manufacturing states of the country, the study found that despite the levels of environmental awareness shown by Malaysian F&B companies, only a small number of the sample have adopted the ISO 14001 standard or are likely to in the future. The decision to adopt ISO 14001 was primarily driven by the motivation to enhance company image and reputation, as well as to improve environmental performance, particularly by large companies. The primary barriers to EMS adoption are the high certification costs, the lack of in-house knowledge, and the lack of government support and incentives. Considering many F&B companies are SMEs operating on narrow profit margins, the ISO 14001 standard is perceived as a disincentive to their organizational performance. The finding suggests that only large and multinational companies will take the necessary action to adopt ISO 14001 since these organizations are more likely to meet the requirements expected of international markets.

There has been a declining share of European imports from Malaysian F&B companies in parallel to an increase in European ISO 14001 certifications. It is argued that adopting EMS standard offers a solution to promote environmental improvement, whilst exposing Malaysian F&B industries beyond national and regional markets. Such an approach will help address boost the entry of Malaysian F&B companies into international markets, which in turn can support dual economic and environmental objectives. Strategies to increase the adoption of EMS within the F&B sector include mandatory regulations, devising national strategies, and a Malaysian internationally recognized EMS standard.

This study primarily focused on F&B company perceptions. Future research can build on these findings by examining the perceptions and expectations amongst a wide range of local, national, and international stakeholders, notably industry representative organizations, governmental agencies, non-governmental organizations, food purchasers and retailers (i.e. catering companies and supermarket chains in different countries), and international standards setting organizations (i.e. ISO). In addition to widening the sample size for future studies, theoretical perspectives can be examined, such as contingency perspectives and stakeholder theory. Further research may also include cross-country investigations to capture the spatial and cultural effect on the drivers, barriers, and incentives to EMS adoption.

Notes

SME Corporation Malaysia (2015) defines small and medium enterprises within manufacturing sector as an establishment which has a sales turnover no more than RM 50 million or full-time employees not exceeding 200 workers.

Following a study by Nishitani (2010), the export ratio is calculated as the value of export (in million MYR) divided by the Malaysian GDP.

References

Adham KN, Merle K, Weihs G (2013) Sustainable consumption and production in Malaysia: a baseline study of government policies, institutions and practices. Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department, Putrajaya

Arimura TH, Darnall N, Katayama H (2011) Is ISO 14001 a gateway to more advanced voluntary action? The case of green supply chain management. J Environ Econ Manage 61:170–182. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2010.11.003

AHK Malaysia (2012) Market watch 2012: the Malaysian food industry. Malaysia-German Chamber of Commerce and Industry. www.malaysia.ahk.de/en/services/market-entry/market-information/food-sector/. Accessed 3 Jan 2017

Bellesi F, Lehrer D, Tal A (2005) Comparative advantage: the impact of ISO 14001 environmental certification on exports. Environ Sci Technol 39:1943–1953. doi:10.1021/es0497983

Bentley M (2008) Planning for change: guidelines for national programmes on sustainable consumption and production. United Nations Environment Programme, Paris

Boiral O, Guillaumie L, Heras-Saizarbitoria I, Tene CVT (2017) Adoption and outcomes of ISO 14001: a systematic review. Int J Manage Rev. doi:10.1111/ijmr.12139

Brammer S, Hoejmose S, Marchant K (2012) Environmental management in SMEs in the UK: practices, pressures and perceived benefits. Bus Strat Environ 21:423–434. doi:10.1002/bse.717

Campos LM (2012) Environmental management systems (EMS) for small companies: a study in Southern Brazil. J Clean Prod 32:141–148. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.03.029

Delmas M, Toffel M (2004) Stakeholders and environmental management practices: an institutional framework. Bus Strat Environ 21:423–434. doi:10.1002/bse.717

DOSM (2017) External trade. Department of Statistics Malaysia. www.dosm.gov.my. Accessed 10 June 2017

Eco-Action 21 (2017) What is eco action 21? Institute for Promoting Sustainable Societies. www.ea21.jp/ea21/index.html. Accessed 9 June 2017

European Commission (2008) Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions on the sustainable consumption and production and sustainable industrial policy action plan. eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/. Accessed 13 Feb 2017

European Commission (2017) Eurostat. epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/newxtweb/. Accessed 10 June 2017

Fan J, Zhao D, Wu Y, Wei J (2014) Carbon pricing and electricity market reforms in China. Clean Technol Environ 16:921–933. doi:10.1007/s10098-013-0691-6

Fryxell GE, Szeto A (2002) The influence of motivations for seeking ISO 14001 certification: an empirical study of ISO 14001 certified facilities in Hong Kong. J Environ Manage 65:223–238. doi:10.1006/jema.2001.0538

Garnett T (2008) Cooking up a storm: food, greenhouse gas emissions and our changing climate. Food Climate Research Network, Guildford

Goh YN, Wahid NA (2015) A review on green purchase behaviour trend of Malaysian consumers. Asian Soc Sci 11:103–110. doi:10.5539/ass.v11n2p103

Gualandris J, Klassen RD, Vachon S, Kalchschmidt M (2015) Sustainable evaluation and verification in supply chains: aligning and leveraging accountability to stakeholders. J Oper Manage 38:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2015.06.002

ISO (2016) ISO survey 2015. International Organization for Standardization. www.iso.org/iso/iso-survey. Accessed 2 Jan 2017

Jiang RJ, Bansal P (2003) Seeing the need for ISO 14001. J Manage Stud 40:1047–1067. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00370

Jones N, Panoriou E, Thiveou K, Roumeliotis S, Allan S, Clark JRA, Evangelinos KI (2012) Investigating benefits from the implementation of environmental management systems in a Greek university. Clean Technol Environ 14:669–676. doi:10.1007/s10098-011-0431-8

KPMG Environmental Consulting (1997) The environmental challenge and small and medium-sized enterprises in Europe. KPMG Environmental Consulting, The Hague

Lee CT, Klemeš JJ, Hashim H, Ho CS (2016) Mobilising the potential towards low-carbon emissions society in Asia. Clean Technol Environ 18:2337–2345. doi:10.1007/s10098-016-1288-7

Lewis KV, Cassells S, Roxas H (2015) SMEs and the potential for a collaborative path to environmental responsibility. Bus Strat Environ 24:750–764. doi:10.1002/bse.1843

Liu X, Klemeš JJ, Varbanov PS, Čuček L, Qian Y (2016) Virtual carbon and water flows embodied in international trade: a review on consumption-based analysis. J Clean Prod 146:20–28. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.03.129

Ludema RD, Wooton I (1994) Cross-border externalities and trade liberalization: the strategic control of pollution. Can J Econ 27:950–966. doi:10.2307/136193

Majumdar SK, Marcus AA (2001) Rules versus discretion: the productivity consequences of flexible regulation. Acad Manage J 44:170–179. doi:10.2307/3069344

Manzo K, Padfield R (2016) Palm oil not polar bears: climate change and development in Malaysian media. Trans Inst Br Geogr 41:460–476. doi:10.1111/tran.12129

Massoud MA, Fayad R, El-Fadel M, Kamleh R (2010) Drivers, barriers and incentives to implementing environmental management systems in the food industry: a case of Lebanon. J Clean Prod 18:200–209. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.09.022

McKeiver C, Gadenne D (2005) Environmental management systems in small and medium businesses. Int Small Bus J 23:513–537. doi:10.1177/0266242605055910

MIDA (2013) Food industry in Malaysia. Malaysian Investment Development Authority. www.mida.gov.my/home/food-technology-and-sustainable-resources/posts/. Accessed 31 May 2016

Neumayer E, Perkins R (2004) What explains the uneven take-up of ISO 14001 at the global level? A panel-data analysis. Environ Plan A 36:823–839. doi:10.1068/a36144

Nikolaou I, Evangelinos KI, Emmanouil D, Leal W (2012) Voluntary versus mandatory EMS implementation: management awareness in EMS-certified firms. Asia Pac J Manage 8:1–12. doi:10.1177/2319510X1200800102

Nishitani K (2010) Demand for ISO 14001 adoption in the global supply chain: an empirical analysis focusing on environmentally conscious markets. Resour Energy Econ 32:395–407. doi:10.1016/j.reseneeco.2009.11.002

NSWMD (2013) Survey on solid waste composition, characteristics & existing practice of solid waste recycling in Malaysia. National Solid Waste Management Department. jpspn.kpkt.gov.my/index.php/pages/view/66. Accessed 23 Jan 2017

OECD (2014) Towards green growth in Southeast Asia. OECD Green Growth Stud. doi:10.1787/9789264224100-en

Padfield R, Papargyropoulou E, Preece C (2012) A preliminary assessment of greenhouse gas emission trends in the production and consumption of food in Malaysia. Int J Technol 3:55–66. doi:10.14716/ijtech.v3i1.81

Papargyropoulou E, Padfield R, Harrison O, Preece C (2012) The rise of sustainability services for the built environment in Malaysia. Sustain Cities Soc 5:44–51. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2012.05.008

Papargyropoulou E, Lozano R, Steinberger JK, Wright N, bin Ujang Z (2014) The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J Clean Prod 76:106–115. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.04.020

Papargyropoulou E, Wright N, Lozano R, Steinberger J, Padfield R, Ujang Z (2016) Conceptual framework for the study of food waste generation and prevention in the hospitality sector. Waste Manag 49:326–336. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2016.01.017

Prajogo D, McDermott CM (2014) Antecedents of service innovation in SMEs: comparing the effects of external and internal factors. J Small Bus Manage 52:521–540. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12047

Prakash A, Potoski M (2006) Racing to the bottom? Trade, environmental governance, and ISO 14001. Am J Polit Sci 50:350–364. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00188.x

Qi GY, Zeng SX, Tam CM, Yin HT, Wu JF, Dai ZH (2011) Diffusion of ISO 14001 environmental management systems in China: rethinking on stakeholders’ roles. J Clean Prod 19:1250–1256. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.03.006

Quazi HA, Khoo YK, Tan CM, Wong PS (2001) Motivation for ISO 14000 certification: development of a predictive model. Omega 29:522–542. doi:10.1016/S0305-0483(01)00042-1

Salim H, Padfield R, Hansen SB, Ali Y, Mohamad S, Syayuti K, Tham M, Papargyropoulou E (2017) Global trends in environmental management systems and ISO14001 research. J Clean Prod. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.09.017

Searchinger T, Hanson C, Ranganathan J, Lipinski B, Waite R, Winterbottom R, Dinshaw A, Heimlich R (2013) Creating a sustainable food future: interim findings. www.wri.org. Accessed 5 Sept 2017

SME Corporation Malaysia (2015) SME definitions. www.smecorp.gov.my. Accessed 29 Jan 2017

Staniškis J, Arbačiauskas V, Varžinskas V (2012) Sustainable consumption and production as a system: experience in Lithuania. Clean Technol Environ. doi:10.1007/s10098-012-0509-y

Steger U (2000) Environmental management systems: empirical evidence and further perspectives. Eur Manage J 18:23–27. doi:10.1016/S0263-2373(99)00066-3

Studer S, Welford R, Hills P (2006) Engaging Hong Kong businesses in environmental change: drivers and barriers. Bus Strat Environ 15:416–431. doi:10.1002/bse.516

Studer S, Tsang S, Welford R, Hills P (2008) SMEs and voluntary environmental initiatives: a study of stakeholders’ perspectives in Hong Kong. J Environ Plan Manage 51:285–301. doi:10.1080/09640560701865073

Tan LP (2005) Implementing ISO 14001: is it beneficial for firms in newly industrialized Malaysia? J Clean Prod 13:397–404. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2003.12.002

Todorov V, Filzmoser P (2010) Robust statistic for the one-way MANOVA. Comput Stat Data Anal 54:37–48. doi:10.1016/j.csda.2009.08.015

Turk AM (2009) The benefits associated with ISO 14001 certification for construction firms: Turkish case. J Clean Prod 17:559–569. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.11.001

UNEP (2012) Global outlook on SCP policies: taking action together. United Nations Environment Programme. Sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Accessed 4 Feb 2017

Zeng SX, Tam CM, Tam VW, Deng ZM (2005) Towards implementation of ISO 14001 environmental management systems in selected industries in China. J Clean Prod 13:645–656. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2003.12.009

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2nd International Conference of Low Carbon Asia & Beyond in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The first author would like to acknowledge Malaysia-Japan International Institute of Technology (MJIIT), Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), for the financial support under the Japan-ASEAN Integration Fund (JAIF) Master scholarship (Vot No: A.k430000.6100.08997). The second author would like to acknowledge Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) for funding this research under the Foreigner Lecturer’s research grant (Vot No: 4D015). A final acknowledgement is also made to Dr. May A. Massoud for her valuable contribution to this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salim, H.K., Padfield, R., Lee, C.T. et al. An investigation of the drivers, barriers, and incentives for environmental management systems in the Malaysian food and beverage industry. Clean Techn Environ Policy 20, 529–538 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-017-1436-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-017-1436-8