Abstract

In this study, the usability and performance of GenomEra™ C. difficile and BD Max™ Cdiff nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for the detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile were investigated in comparison with toxigenic culture and C. difficile toxin A- and toxin B-detecting immunochromatographic antigen (IA) test, the Tox A/B QuikChek®. In total, 302 faecal specimens were collected, 113 of which were in parallel to conventional sample containers and FecalSwab liquid-based microbiology (LBM) tubes. Seventy-nine specimens were considered true-positives for toxigenic C. difficile. The sensitivity and specificity were 97.5 % and 99.6 % and 93.7 % and 98.7 % for the GenomEra and BD Max assays respectively. Toxigenic culture and Tox A/B QuikChek had sensitivity and specificity of 91.1 % and 100 % and 34.2 % and 100 % respectively. Hands-on time for analysing 1 to 24 specimens using NAATs was 1 to 15 min. The rate of PCR inhibition was 0 % for both NAATs with faeces in LBM tubes, while with faeces in conventional sample containers the respective inhibition rates were 5.3 % and 4.4 % for the GenomEra and the BD Max assays. The NAATs demonstrated an excellent analytical performance, reducing significantly the overall workload of laboratory personnel compared with culture and IA test.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clostridium difficile, a Gram-positive anaerobic rod, is recognised as one of the commonest causes of hospital-acquired and antibiotic-associated diarrhoea throughout the world [1, 2]. C. difficile infection (CDI) results from the main virulence factors, toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdB), produced by the bacterium [3, 4]. In addition, a separate binary toxin, which is produced by a group of isolates with or without TcdA and/or TcdB [5, 6], has been suggested to play a part in the recurrence and in the severity of CDI [7]. As CDI is associated with an increase in the length of hospitalization and mortality, leading to augmented health-care costs [2, 6, 8], the rapid and reliable detection of toxigenic C. difficile is important.

Traditionally, culture-based methods, such as cytotoxigenic culture and cytotoxin assay, have been used as a gold standard for C. difficile screening. These are known to be cost-effective but time-consuming approaches [9–13]. An alternative approach is the detection of C. difficile toxins or glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) in stool samples using immunochromatographic antigen (IA) tests or enzyme immunoassays (EIA) [14–16]. Although more rapid, these assays have been shown to be less sensitive and less specific than culture. Furthermore, relying only on GDH detection reveals nothing on the toxigenic nature of the possible C. difficile isolates.

In recent years, the direct detection of genes encoding C. difficile toxin A and/or toxin B with nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) has become a diagnostic target of interest [17–19]. NAATs have shown to be more sensitive than IA or EIA and in some studies even more sensitive than the cytotoxigenic culture or cytotoxin assay [14, 20–26]. The main advantage of NAATs, in addition to the high sensitivity and specificity, is the short turn-around time, compared with conventional culture. As the number of different NAATs for the detection of toxigenic C. difficile is rapidly increasing, comprehensive studies to determine the assay’s quality and usefulness in clinical laboratories and for point-of-care (POC) settings are required.

Here, we investigated the usability of two recently launched, tcdB gene-detecting, PCR assays, the GenomEra C. difficile (Abacus Diagnostica, Turku, Finland), and the BD Max Cdiff (Becton, Dickinson and Company, NJ, USA) for the detection of C. difficile in faecal specimens. Results were analysed in comparison with a single-use POC compatible IA test, the Tox A/B QuikChek® (Alere Limited, Stockport, UK) and toxigenic culture. Along with the assessment of performance, workload analysis and the ease of result interpretation were conducted for each test. Apart from the method comparison, the utility of a liquid-based microbiology (LBM) tube, the FecalSwab (Copan Italia, Brescia, Italy), for the screening of C. difficile was also investigated.

Materials and methods

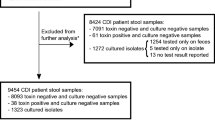

A total of 302 loose stool specimens, one specimen per patient, were prospectively collected from inpatients (the patients’ mean age was 70 years, ages ranging from 7 to 95 years) at Vaasa Central Hospital, Finland, according to hospital routine practice in antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Of these, 185 were collected into conventional sample containers and 113 were collected in parallel into one sample container and FecalSwab LBM tube. All specimens were analysed immediately after receipt into the laboratory using all four methods: the GenomEra™ C. difficile, the BD Max Cdiff™ assay, the Tox A/B QuikChek® and toxigenic culture.

Both NAATs and the IA test were performed as described in previous studies [27–29], according to the manufacturer’s instructions. However, a minor variation with the BD Max Cdiff assay for sample collection was implemented when specimens were in FecalSwabs. Fifty microliters of homogenised stool was used for the assay run, rather than 10 μL, as it was found to be the optimal amount of sample in the BD Max buffer tube (data not shown). Toxigenic culture was performed by plating the specimen on cycloserine cefoxitin egg-yolk agar (CCEY) medium (Oxoid Limited, Basingstoke, UK) and incubating the plate for 48 h in an anaerobic atmosphere at +35 °C. Presumed growth of C. difficile and the toxigenic nature of the bacterium were confirmed by Gram staining, UV light, and the IA test (Wampole C. diff QuikChek Complete; Alere Limited) targeting C. difficile-specific glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and C. difficile toxins A and B. Hands-on time and total turnaround time for each test method were assessed by investigating the time elapsed for 1 to 24 specimens by three laboratory specialists.

Specimens were defined as true-positive for toxigenic C. difficile when the bacterium was isolated and its toxin production was confirmed by toxigenic culture, or when both NAATs reported a positive tcdB result regardless of a negative growth result in toxigenic culture, or when one of the NAATs in conjunction with the IA assay yielded a positive result regardless of a negative growth result in toxigenic culture. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the statistical significance of the differences among the various test methods.

Results

Of the 302 stool specimens, 79 (26.2 %) were considered true-positive for toxigenic C. difficile. Seventy-two (91.1 %) specimens yielded the growth of toxin-producing C. difficile and 7 (8.9 %) specimens were tcdB positive by both NAATs while being culture negative (Table 1). Furthermore, the BD Max Cdiff reported three additional positive results and the GenomEra C. difficile reported one positive result, which, however, remained negative according to all other methods and, thus, were determined as false-positives.

Of the 79 true-positive specimens, the BD Max Cdiff detected 74 and the GenomEra C. difficile detected 77 (Table 1). Using the Tox A/B QuikChek IA test, only 27 of the 79 specimens were detected as positive. The respective sensitivity and specificity were 91.1 % (95 % CI, 84.8–97.4 %) and 100 % for toxigenic culture, 93.7 % (95 % CI, 88.3–99.1 %) and 98.7 % (95 % CI, 97.2–100 %) for the BD Max, 97.5 % (95 % CI, 94.1–100 %) and 99.6 % (95 % CI, 98.8–100 %) for the GenomEra, and 34.2 % (95 % CI, 23.7–44.7 %) and 100 % for the Tox A/B QuikChek IA test. Positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) were 100 % and 97.0 % for toxigenic culture, 96.3 % and 97.8 % for the BD Max, 98.8 % and 99.1 % for the GenomEra, and 100 % and 81.1 % for the Tox A/B QuikChek IA respectively.

The PCR inhibition rate of the BD Max was 4.4 % (5 out of 113) with faeces in conventional containers and 0 % (0 out of 113) with faeces in FecalSwabs. The PCR inhibition rate of the GenomEra was 5.3 % (6 out of 113) with faeces in conventional containers and 0 % (0 out of 113) with faeces in FecalSwabs.

Hands-on time for analysing 1 to 4 specimens was 1 to 2.5 min for the GenomEra, 1.5 to 3 min for the BD Max, 2.5 to 5.5 min for the Tox A/B QuikChek IA test, and 5 to 10 min for culture (Table 2). Further, the test run time for the same amount of specimens was 55 min with the GenomEra, 85 min with the BD Max, and 25 min with the Tox A/B QuikChek. Using culture, approximately 48 h was needed for each specimen in the final results. To analyse 24 specimens, the hands-on time was 15 min for the GenomEra, 10 min for the BD Max, 38 min for the Tox A/B QuikChek, and 110 min for culture.

Result interpretation was considered to be easiest with the NAATs, and least agreeable with the Tox A/B QuikChek owing to the variable quality of the colour line indicating a positive result. With the GenomEra assay the test results were reported by the assay software in numerical form from −15 (negative) to +100 (strongly positive) for the tcdB together with a written conclusion: “C. difficile tcdB negative”, “inconclusive”, or “positive”. The BD Max assay reported amplification curves and Ct values, together with a written conclusion: “C. difficile toxin B positive” or “negative”. Oddly, in 2 cases the BD Max instrument reported a negative test result, while on the raw data sheet a low but definite amplification curve for the tcdB target was seen. These specimens were positive according to the GenomEra. In addition, in one case the BD Max reported a positive test result, although there was no amplification curve visible. This specimen was negative according to all other methods.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to compare the performance of two new automated NAATs, the GenomEra C. difficile and the BD Max Cdiff, and to investigate their utility for the detection of toxigenic C. difficile in comparison with the POC-compatible toxin A/B IA test and toxigenic culture. Both NAATs demonstrated excellent sensitivity and specificity in our sample material (AAD patients). There were 7 (8.9 %) confirmed positive C. difficile specimens in which the infectious agent was only detectable by the NAATs and not by culture. This finding is consistent with previous studies investigating the performances of various test methods for the detection of toxigenic C. difficile [14, 20–27]. Differences in sensitivity between the NAATs and culture were not, however, significant (P value > 0.5). An additional 4 specimens were reported to be positive by one of the NAATs (3 by the BD Max and 1 by the GenomEra), but these could not be confirmed by any other tests, and were thus considered false-positives.

Compared with the POC-compatible toxin A/B IA test, NAATs improved significantly the detection of toxigenic C. difficile (P value < 0.0001), a finding that is also familiar from earlier reports [14, 20–26]. Thus, when toxin A/B IA tests are used as stand-alone tests in clinical microbiological laboratories, many clinical presentations compatible with CDI may remain without confirmation or may be erroneously considered C. difficile-negative. Moreover, IA tests are prone to subjective result interpretation, unlike the automated NAATs. The detection of CDI with IA or EIA tests may be improved using 2- to 3-step diagnostic algorithms [30]. These approaches combine a preliminary GDH screening test (more sensitive test) with toxin A- and/or toxin B-detecting EIA, NAATs or culture. Recent studies have, however, demonstrated that the sensitivity of 2- to 3-step algorithms may still be as low as 41–68 % [31]. In addition, these approaches undoubtedly increase the workload of laboratory personnel and extend the total turnaround time.

It should be noted, though, that the level of sensitivity needed for CDI diagnostic testing is not yet clear, as stated recently by Stellrecht et al. [28]. It has been assumed that sensitive methods, such as culture or NAATs, are not able to discriminate between CDI and asymptomatic colonisation, as the asymptomatic carriage of toxigenic C. difficile among children and elderly inpatients, and among patients in extended care facilities (i.e. nursing homes), can be common [32–35]. However, the detection of asymptomatic carriage may have relevance, if the diagnostic purpose is to investigate the transmission of C. difficile in different health care settings [32, 35]. Thus, good practice requires careful consideration of testing indication, and in the case of CDI, attention should be paid to performing NAATs on symptomatic patients only [31].

In some recently published studies, NAATs have been stated to be an uneconomical choice for the screening of toxigenic C. difficile because of the higher cost of reagents and consumables compared with culture or IA tests [15, 16]. However, Brecher et al. highlighted in their recent review that although the cost of a test is low, it is of little value if the result is inaccurate and has to be repeated many times over several days to get an accurate result [31]. We observed that hands-on time in addition to the total processing time was considerably shorter with the BD Max Cdiff and with the GenomEra C. difficile than with IA or culture. Hence, NAATs reduces labour costs. Furthermore, using the NAATs, the results were reported more reliably and more rapidly, which we believe to be essential in decreasing the need for retesting and in reducing unnecessary treatment and isolation of patients.

As regards PCR inhibition, it is known to have a notable effect on the diagnostic performance of the NAATs [36]. Thus, by eliminating the problems due to inhibitors, the NAATs are clearly superior to the conventional test methods. In our study, no PCR inhibition was observed with faeces in FecalSwabs, while with faeces in conventional sample containers the inhibition rates were 4.4 % and 5.3 %, depending on the test used. Although the number of specimens tested for this particular study phase was quite low (n = 113), this finding may still provide useful information for further experiments on LBM tubes, improving the utility and performance of the automated NAATs. Because of a more homogenised and diluted form, specimens in FecalSwab tubes are more suitable for use with the NAATs than specimens in conventional containers. Furthermore, LBM tubes have proved to be suitable for extended storage and transportation of enteric pathogens, including toxigenic C. difficile [37], enabling successful and reliable microbiological analysis when specimens are sent to either a local laboratory or a more distant reference laboratory.

In conclusion, the BD Max Cdiff and the GenomEra C. difficile assays are both accurate and well-performing diagnostic tests for the rapid and reliable detection of C. difficile. The GenomEra C. difficile have proved to be optimal for smaller laboratories performing less than 24 analyses per day, and the BD Max Cdiff proved to be suitable for medium-sized laboratories performing 24 or more analyses per day. When the overall process is optimised, including appropriate sample selection, collection and transportation, reduction of PCR inhibition, and reporting the results promptly to physicians, these NAATs can be of maximal use for improving CDI diagnostics and patient outcome.

References

Bartlett JG, Gerding DN (2008) Clinical recognition and diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 46:S12–S18. doi:10.1086/521863

Karas JA, Enoch DA, Aliyu SH (2010) A review of mortality due to Clostridium difficile infection. J Infect 61:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2010.03.025

Kuehne SA, Cartman ST, Heap JT, Kelly ML, Cockayne A, Minton NP (2010) The role of toxin A and toxin B in Clostridium difficile infection. Nature 467:711–713. doi:10.1038/nature09397

Lyras D, O’Connor JR, Howarth PM, Sambol SP, Carter GP, Phumoonna T, Poon R, Adams V, Vedantam G, Johnson S, Gerding DN, Rood JI (2009) Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature 458:1176–1179. doi:10.1038/nature07822

Elliott B, Squire MM, Thean S, Chang BJ, Brazier JS, Rupnik M, Riley TV (2011) New types of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive strains among clinical isolates of Clostridium difficile in Australia. J Med Microbiol 60:1108–1111. doi:10.1099/jmm. 0.031062-0

Warny M, Pepin J, Fang A, Killgore G, Thompson A, Brazier J, Frost E, McDonald LC (2005) Toxin production by an emerging strain of Clostridium difficile associated with outbreaks of severe disease in North America and Europe. Lancet 366:1079–1084. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67420-X

Stewart DB, Berg A, Hegarty J (2013) Predicting recurrence of C. difficile colitis using bacterial virulence factors: binary toxin is the key. J Gastrointest Surg 17:118–124. doi:10.1007/s11605-012-2056-6

Dodek PM, Norena M, Ayas NT, Romney M, Wong H (2013) Length of stay and mortality due to Clostridium difficile infection acquired in the intensive care unit. J Crit Care 28:335–340. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.11.008

Arroyo LG, Rousseau J, Willey BM, Low DE, Staempfli H, McGeer A, Weese JS (2005) Use of a selective enrichment broth to recover Clostridium difficile from stool swabs stored under different conditions. J Clin Microbiol 43:5341–5343. doi:10.1128/JCM. 43.10.5341-5343.2005

Bliss DZ, Johnson S, Clabots CR, Savik K, Gerding DN (1997) Comparison of cycloserine-cefoxitin-fructose agar (CCFA) and taurocholate-CCFA for recovery of Clostridium difficile during surveillance of hospitalized patients. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 29:1–4

Clabots CR, Gerding SJ, Olson MM, Peterson LR, Gerding DN (1989) Detection of asymptomatic Clostridium difficile carriage by an alcohol shock procedure. J Clin Microbiol 27:2386–2387

Marler LM, Siders JA, Wolters LC, Pettigrew Y, Skitt BL, Allen SD (1992) Comparison of five cultural procedures for isolation of Clostridium difficile from stools. J Clin Microbiol 30:514–516

Brazier JS (1998) The diagnosis of Clostridium difficile-associated disease. J Antimicrob Chemother 41:29–40

Bruins MJ, Verbeek E, Wallinga JA, Bruijnesteijn van Coppenraet LE, Kuijper EJ, Bloembergen P (2012) Evaluation of three enzyme immunoassays and a loop-mediated isothermal amplification test for the laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31:3035–3039. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1658-y

Culbreath K, Ager E, Nemeyer RJ, Kerr A, Gilligan PH (2012) Evolution of testing algorithms at a university hospital for detection of Clostridium difficile infections. J Clin Microbiol 50:3073–3076. doi:10.1128/JCM. 00992-12

Walkty A, Lagacé-Wiens PR, Manickam K, Adam H, Pieroni P, Hoban D, Karlowsky JA, Alfa M (2013) Laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infection—evaluation of an algorithmic approach in comparison with the Illumigene® assay. J Clin Microbiol 51:1152–1157. doi:10.1128/JCM. 03203-12

Alonso R, Muñoz C, Peláez T, Cercenado E, Rodríguez-Creixems M, Bouza E (1997) Rapid detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile strains by a nested PCR of the toxin B gene. Clin Microbiol Infect 3:145–147

Bélanger SD, Boissinot M, Clairoux N, Picard FJ, Bergeron MG (2003) Rapid detection of Clostridium difficile in feces by real-time PCR. J Clin Microbiol 41:730–734. doi:10.1128/JCM. 41.2.730-734.2003

Kato H, Kato N, Watanabe K, Iwai N, Nakamura H, Yamamoto T, Suzuki K, Kim SM, Chong Y, Wasito EB (1998) Identification of toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile by PCR. J Clin Microbiol 36:2178–2182

Dubberke ER, Han Z, Bobo L, Hink T, Lawrence B, Copper S, Hoppe-Bauer J, Burnham CA, Dunne WM Jr (2011) Impact of clinical symptoms on interpretation of diagnostic assays for Clostridium difficile infections. J Clin Microbiol 49:2887–2893. doi:10.1128/JCM. 00891-11

Eastwood K, Else P, Charlett A, Wilcox M (2009) Comparison of nine commercially available Clostridium difficile toxin detection assays, a real-time PCR assay for C. difficile tcdB, and a glutamate dehydrogenase detection assay to cytotoxin testing and cytotoxigenic culture methods. J Clin Microbiol 47:3211–3217. doi:10.1128/JCM. 01082-09

Buchan BW, Mackey TL, Daly JA, Alger G, Denys GA, Peterson LR, Kehl SC, Ledeboer NA (2012) Multicenter clinical evaluation of the portrait toxigenic C. difficile assay for detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile strains in clinical stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol 50:3932–3936. doi:10.1128/JCM. 02083-12

Chapin KC, Dickenson RA, Wu F, Andrea SB (2011) Comparison of five assays for detection of Clostridium difficile toxin. J Mol Diagn 13:395–400. doi:10.1016/j.jmoldx.2011.03.004

Le Guern R, Herwegh S, Grandbastien B, Courcol R, Wallet F (2012) Evaluation of a new molecular test, the BD Max Cdiff, for detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile in fecal samples. J Clin Microbiol 50:3089–3090. doi:10.1128/JCM. 01250-12

Shin BM, Mun SJ, Yoo SJ, Kuak EY (2012) Comparison of BD GeneOhm Cdiff and Seegene Seeplex ACE PCR assays using toxigenic Clostridium difficile culture for direct detection of tcdB from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol 50:3765–3767. doi:10.1128/JCM. 01440-12

Terhes G, Urbán E, Sóki J, Nacsa E, Nagy E (2009) Comparison of a rapid molecular method, the BD GeneOhm Cdiff assay, to the most frequently used laboratory tests for detection of toxin-producing Clostridium difficile in diarrheal feces. J Clin Microbiol 47:3478–3481. doi:10.1128/JCM. 01133-09

Hirvonen JJ, Mentula S, Kaukoranta S-S (2013) Evaluation of a new automated homogeneous PCR assay, GenomEra C. difficile, for rapid detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile in fecal specimens. J Clin Microbiol 51:2908–2912. doi:10.1128/JCM. 01083-13

Stellrecht KA, Espino AA, Maceira VP, Nattanmai SM, Butt SA, Wroblewski D, Hannett GE, Musser KA (2014) Premarket evaluations of the IMDx C. difficile for Abbott m2000 assay and the BD Max Cdiff assay. J Clin Microbiol 52:1423–1428. doi:10.1128/JCM. 03293-13

Quinn CD, Sefers SE, Babiker W, He Y, Alcabasa R, Stratton CW, Carroll KC, Tang Y-W (2010) C. Diff QuikChek Complete enzyme immunoassay provides a reliable first-line method for detection of Clostridium difficile in stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol 48:603–605. doi:10.1128/JCM. 01614-09

Crobach MJ, Dekkers OM, Wilcox MH, Kuijper EJ (2009) European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID): data review and recommendations for diagnosing Clostridium difficile-infection (CDI). Clin Microbiol Infect 15:1053–1066. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03098.x

Brecher SM, Novak-Weekley SM, Nagy E (2013) Laboratory diagnosis of Clostridium difficile infections: there is light at the end of the colon. Clin Infect Dis 57:1175–1181. doi:10.1093/cid/cit424

Rousseau C, Poilane I, De Pontual L, Maherault AC, Le Monnier A, Collignon A (2012) Clostridium difficile carriage in healthy infants in the community: a potential reservoir for pathogenic strains. Clin Infect Dis 55:1209–1215. doi:10.1093/cid/cis637

Matsuki S, Ozaki E, Shozu M, Inoue M, Shimizu S, Yamaguchi N, Karasawa T, Yamagishi T, Nakamura S (2005) Colonization by Clostridium difficile of neonates in a hospital, and infants and children in three day-care facilities of Kanazawa, Japan. Int Microbiol 8:43–48

Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, Kelly CP (2000) Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile and serum levels of IgG antibody against toxin A. N Engl J Med 342:390–397

Riggs MM, Sethi AK, Zabarsky TF, Eckstein EC, Jump RL, Donskey CJ (2007) Asymptomatic carriers are a potential source for transmission of epidemic and nonepidemic Clostridium difficile strains among long-term care facility residents. Clin Infect Dis 45:992–998. doi:10.1086/521854

Pasternack R, Vuorinen P, Kuukankorpi A, Pitkäjärvi T, Miettinen A (1996) Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis infections in women by Amplicor PCR: comparison of diagnostic performance with urine and cervical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 34:995–998

Hirvonen JJ, Kaukoranta SS (2014) Comparison of FecalSwab and ESwab devices for storage and transportation of diarrheagenic bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 52:2334–2339. doi:10.1128/JCM. 00539-14

Acknowledgements

Nancy Lahtinen, Mikaela Eur, and Marianne Nynäs are gratefully acknowledged for their help in sample preparations and workload analysis. We have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hirvonen, J.J., Kaukoranta, SS. Comparison of BD Max Cdiff and GenomEra C. difficile molecular assays for detection of toxigenic Clostridium difficile from stools in conventional sample containers and in FecalSwabs. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 34, 1005–1009 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-015-2320-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-015-2320-2