Abstract

Purpose

Head and neck cancer (HNC) patients experience multiple physical and psychosocial symptoms associated with their cancer treatment. The Easing and Alleviating Symptoms during Treatment (EASE) study utilized a mixed methods design to examine the feasibility of a tailored telephone-based coping and stress management intervention to improve symptom management and psychosocial care among HNC patients.

Methods

An Embedded Correlational Mixed Methods Design was utilized to answer two research questions: (1) is the EASE intervention feasible? and (2) Did EASE participants report improvements in psychosocial outcomes after completion of the EASE intervention? HNC patients were assessed at baseline and 3 months. Psychosocial measures included cancer-specific distress, pain, social support, and quality of life. Project records and exit interviews were conducted to assess acceptability and satisfaction with the intervention.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 60 years (SD = 9.5), 76 % were male, 47 % married/partnered, and 57 % had a history of tobacco use. Of the 24 participants who were enrolled, 16 completed the intervention. Participants and telephone counselors reported high levels of satisfaction. Although the small sample size and lack of a control group limit our ability to assess the efficacy of the intervention, our findings suggest that the intervention helped to buffer the negative emotional and physical impact of cancer treatment.

Conclusions

This pilot study demonstrated that the EASE intervention is feasible and acceptable to HNC cancer patients undergoing treatment. The study findings revealed some challenges of implementing a psychosocial intervention in HNC patients and inform future intervention studies with this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) is one of the most traumatic forms of cancer because of the impact on fundamental aspects of living (i.e., eating, breathing, and swallowing) and the potential for long-term dysfunction and disfigurement [1]. Treatment for many head and neck cancers includes concomitant chemotherapy and radiation treatment, which is associated with a number of significant physical and social–emotional side effects [2, 3]. HNC patients have poorer quality of life (QOL) [4–6], higher frequency (30–40 %) of distress [7–10], and an increased risk of suicide compared to other cancer patients [11, 12]. Although some of these problems gradually resolve following the cessation of treatment, a large proportion (24–50 %) of HNC patients report chronic dysfunction [7, 13, 14], which can result in psychological difficulties [8]. Recent studies have reported a strong association between psychosocial factors, quality of life, and survival in head and neck cancer patients [15, 16]

Psychosocial interventions for head and neck cancer patients

To date, there are a limited number of published psychosocial intervention studies—defined broadly as interventions that include psychological, behavioral, and psychoeducational components—assessing QOL outcomes in HNC patients. These studies include a mixture of content (e.g., patient education, coping skills training) and modalities (e.g., individual, group-based) making cross comparisons difficult. Hammerlid [17, 18] tested the impact of a long-term psychological group therapy for newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients [17]; therapy cases demonstrated improvement in QOL compared to controls. The second trial assessed the impact of a short-term psychoeducational program for patients at 1-year posttreatment. The intervention group showed improvements in measures of physical symptoms and functioning [18]. A study by Petruson and colleagues [19] found no difference in health-related quality of life between controls and participants who engaged in repeated meetings with a multidisciplinary medical team for 1 year following their initial cancer diagnosis. Allison and colleagues [20] reported positive findings from a pilot study examining the feasibility of a coping intervention that offered participants a choice of several intervention modalities, including individual, group, and home-format options. Participants experienced improvements in global quality of life and reductions in depressive symptoms. In another study, HNC patients with posttreatment psychosocial dysfunction were able to self-select into an individualized problem-focused intervention or a control condition. The intervention group reported decreases in psychological distress and improved social functioning and quality of life scores [21]. Research suggests that psychosocial interventions, especially those that contain elements of cognitive–behavioral therapy, can have a significant impact on various QOL outcomes [22]. In terms of the modality, a survey of HNC patients who recently completed cancer treatment reported a preference for individual psychosocial interventions over group-based programs, bibliotherapy, or computer-assisted therapy [23].

The method for delivering psychosocial interventions can also impact the success of the intervention. The telephone is frequently utilized as an acceptable and valid modality for delivering psychosocial interventions. Previous work demonstrates that telephone-based psychosocial interventions aimed at decreasing distress and improving clinical outcome are effective and efficacious for a variety of medical patients [24–28]. A telephone-based intervention is particularly relevant to HNC patients undergoing treatment; it decreases the burden of coming into the clinic for additional visits, and it is able to reach those with geographical barriers, poor social support, and/or treatment-related symptoms that can hinder the desire and ability to travel away from their home [29–31]. Some of the disadvantages of the telephone is that the counselor is unable to assess the patients’ nonverbal behaviors and expressions. Additionally, HNC patients who find it difficult to speak, suffer from a hearing impairment, or experience attention and/or concentration problems would find it challenging to participate in a telephone-based intervention.

The goals of this pilot study were to: (1) test the feasibility and acceptability of a psychosocial intervention delivered by telephone [Easing and Alleviating Symptoms during Treatment (EASE)] designed to improve symptom management in newly diagnosed HNC patients undergoing cancer treatment and (2) to provide a preliminary assessment of the intervention benefits among EASE participants. The EASE intervention involved (1) an ongoing systematic assessment of physical, psychosocial, and functional needs; (2) a psychoeducational component geared toward the management of treatment side effects, and (3) coping skills training to facilitate adaptive coping and improve self-care and symptom management. A recent review of the literature did not produce any published empirical studies in oncology testing a psychosocial intervention delivered by telephone to aid HNC patients with information and techniques to cope with treatment-related symptoms.

Methods

Study design and partcipant enrollment

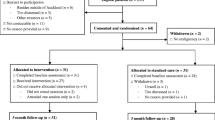

An Embedded Correlational Mixed Methods Design [32] was applied based on the assumption that solely relying on a quantitative approach would not sufficiently answer the two research questions stated above; therefore, qualitative data components were embedded within the quantitative correlational design to examine the process of the EASE intervention [32]. Figure 1 graphically displays the use of the mixed methods analysis.

Diagram notation of mixed methods analysis of EASE intervention. QUAL qualitative data collection, QUANT quantitative data collection. Diagram notation of mixed methods provided by Creswell and Plano-Clark [32]

Potential participants were identified and recruited from a university-based Radiation Oncology Clinic at the time of their initial consult. Eligibility criteria included: (1) a recent diagnosis of cancer of the head and neck, (2) receiving curative treatment that included radiotherapy, (3) access to a telephone, (4) English speaking, and (5) no overt psychosis or other medical or psychological condition that could interfere with the ability to consent and/or participate in the program. The study was approved by an Institutional Review Board and was compliant with the current HIPAA regulations and guidelines [33]. Due to the correlational nature of the study design, convenience sampling was imposed to evaluate the feasibility of the EASE intervention. Enrollment into the study and written informed consent took place at the time of the radiotherapy consult or during one of the treatment visits. Given that these conversations occurred in a private area, and the intervention was delivered by phone to patients in their home, there were no ethical concerns regarding other patient’s desire to receive additional services via the EASE program.

The EASE intervention

EASE utilized the empirically supported Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (TMSC) as a conceptual model. TMSC predicts that those who are able to handle and adapt to the challenges of cancer treatment will experience lower levels of distress and higher quality of life [24, 34]. Transactional-based interventions utilizing cognitive–behavioral intervention strategies are associated with improved coping and adaptation to stressful life events [10]. The EASE intervention aimed to facilitate adaptive appraisals of stress and active coping among participants, as well as reduce emotional distress and increase self-efficacy related to symptom management. EASE included up to eight telephone counseling sessions delivered during the course of cancer treatment. Telephone sessions were scheduled to correspond with key phases in the illness treatment continuum (e.g., time of diagnosis, active treatment, and end of treatment), and the number of sessions was determined by the length of the patient’s treatment. Although the EASE intervention was tailored and adapted to meet the unique needs of HNC patients, the foundation of the EASE intervention was strongly based on the evidence-based cognitive–behavioral stress management model established and tested by Antoni and colleagues which is associated with decreases in distress and improvements in quality of life in other cancer populations [35, 36]. In addition to stress management and coping skills training, EASE also provided psychoeducation aimed at increasing understanding of treatment-related factors (i.e., treatment side effects, mechanisms of treatment, and cancer-specific knowledge) with the aim of improving self-care behaviors.

Outcome measures

Telephone assessment interviews were conducted at baseline and at 1 month following completion of the intervention to provide a preliminary assessment of the intervention benefits. The baseline interviews included a battery of quantitative outcome measures that were completed on average of 9.29 days (SD = 6.89) following recruitment into the project. In addition to the quantitative measures used in the baseline assessment, the post-intervention interview also included qualitative process evaluation questions to assess acceptability and satisfaction with the intervention. Table 1 includes an overview of the key outcome variables. The interviews were conducted by professional telephone interviewers from the Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing Unit at the University of Colorado which has completed in excess of 100,000 telephone interviews, the vast majority of which were funded by the National Cancer Institute, Center for Disease Control, and the American Cancer Society. The data collected by the interviewers were directly entered into an IRB-approved ACCESS database that was later transferred into an SPSS database.

In addition to the pre- and post-intervention assessments, eight participants completed qualitative exit interviews consisting of 22 open-ended questions regarding recruitment procedures, intervention process (timing, content, and use of telephone), overall impressions of the program, and suggestions for improvement (see Table 2). The qualitative elements of these interviews were transcribed by the research assistant and entered into a single database using NVivo Qualitative software, with qualitative responses label by participant ID [37]. To evaluate the feasibility of the EASE program, detailed project records were analyzed. These records included qualitative and quantitative data: (1) participation rates, (2) number of telephone counseling sessions completed, (3) debriefing calls with the telephone counselors asking about their impressions of the acceptability and effectiveness of the intervention (see Table 2), and (4) counselor notes detailing the symptoms endorsed by the participant, issues covered during the session, and any resulting action plan.

Data analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed to provide support for the two research questions. Regarding the quantitative data, descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages), effect sizes (Cohen’s d), and nonparametric correlations (τ) were computed. Following Cohen’s [38] guidelines, .20 is small effect, .50 is a medium effect, and .80 depicts a large effect. Since the research was conducted as an intervention-only design, observed effect sizes may not be exclusively attributed to our intervention. All effect sizes are corrected for scale direction, with positive values indicating a desired outcomes (e.g., decrease in distress, increase in social support, and quality of life) and negative value depicting an undesired outcome. Due to the limited sample size, significance testing was not conducted and p values are not reported. Qualitative data were analyzed using constant comparison techniques and extracting themes that emerged within the data and achieved saturation. Finally, the quantitative results were compared to the qualitative findings to determine if the two data sources supported or contradicted each other.

Results

The results described below include both the qualitative and quantitative findings used to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and participant satisfaction of the EASE intervention (research question 1). This section also describes the psychosocial outcomes in order to determine the potential effectiveness of the intervention (research question 2) as well as suggestions for future implementation as stated by the participants and the telephone counselors.

Feasibility: recruitment and retention

A total of 28 participants were approached, and 24 enrolled in the project over the 12-month accrual period. Of the 24 participants who enrolled in the study, 21 completed the baseline assessment and 16 completed the intervention, receiving a range of two to ten sessions (five individuals received one to three sessions, eight received four to six sessions, and three received seven to ten sessions). Eleven participants completed all assessment points, resulting in a 52.3 % retention rate when accounting for those who died during the course of the intervention (n = 2). A flow diagram of the EASE study is presented in Fig. 2.

Participants who started but did not complete the EASE program were more likely to be younger, divorced or never married, and employed full time or on disability. Demographic and medical characteristics of the 21 participants that completed the initial assessment are displayed in Table 3.

Acceptability of the EASE intervention

Information about acceptability of the intervention was gathered via project records, the process evaluation questions included in the final assessment, post-intervention interviews with the participants, and debriefing calls with the telephone counselor. Qualitative analysis of these data indicates that the delivery method, timing, and format of the EASE intervention were acceptable to the majority of the participants. Regarding the delivery of counseling via telephone calls, the majority of participants agreed that phone counseling was preferred, with two participants opposing the use of phone counseling attributing their lack of satisfaction to the impersonal nature of this form of communication. In terms of the number of calls, a few participants suggested reducing the number of counseling calls, especially on days when they received cancer treatment, and three participants suggested increasing the frequency of calls. When asked about the utility of receiving counseling calls while undergoing cancer treatment, the majority of participants (66.7 %) felt that their treatment-related side effects interfered with the counseling calls. The process of conducting the telephone counseling intervention was viewed positively by the telephone counselors. The counselors rated at least half of the participants (56.3 %) as being “highly responsive” to the counseling sessions and reported that participants were most engaged in the counseling intervention at the beginning of their cancer treatment (56.3 %), with less engagement found in the middle (18.8 %) and end of treatment (25.0 %).

It is important to note that three participants were unable to participate in the exit interviews because of health and/or logistical issues. Review of their process evaluation responses indicated that they all had overwhelmingly positive reviews of the study. Based on these follow-up assessments, it appears they would have positively impacted the acceptability and satisfaction outcomes associated with the exit interviews had they participated in this process.

Satisfaction with the EASE intervention

Exit interview data suggest that the majority of participants were highly satisfied with the EASE program. For example, one participant stated “It worked out really well for me. I enjoyed it. I enjoyed talking to my counselor, and everything was really great. I think it’s a good program.” Despite the majority of participants (63 %) being satisfied with the program, three participants agreed with the statement, “this program as not very useful” because (as stated as the reason by each of the three), they “already had a good support system,” their “symptoms were not very severe,” and they had “extensive knowledge about their treatment.” However, these three participants also displayed an improvement in various psychosocial outcomes following the completion of the EASE intervention.

Preliminary psychosocial outcomes

A small decrease in participants’ cancer-specific distress was observed between the two time points, displayed by the small positive effect sizes found for the Impact of Events Scale (IES), on both the Intrusive and Avoidance subscales (Table 4). Participants experienced a decrease in HNC-specific QOL (e.g., problems related to eating, drinking, and speaking; more head and neck related pain), small decrease in the domains of functional and physical well-being, and no substantial change in emotional and social/family well-being. Participants displayed no change in their pain scores and a small decrease in perceived social support.

Suggestions for future implementation

To gain a deeper understanding of how the EASE program could be improved, participants and counselors were asked for suggestions for future implementation. Two suggestions emerged. The first suggestion was to have the counselor and the patient meet prior to beginning the telephone counseling intervention. Counselors and participants agreed that an initial face-to-face meeting would “have helped establish a trust.” One of the participants who had an opportunity to engage in a face-to-face meeting with their counselor stated that because of this meeting, “I had a little better understanding and feel; I could relate and communicate better because I had seen my counselor at least once and she was a person and not a voice over the phone.”

The other frequent suggestion revolved around the timing of the counseling sessions. The majority of participants felt that it would have been helpful to talk to the counselor prior to the onset of cancer treatment. One participant stated, “That might be a good idea [starting the intervention prior to treatment] because obviously many people would feel apprehensive when you learn you’ve been diagnosed with cancer.” Additionally, a few participants suggested extending counseling after treatment was completed to assist them in managing long-term side effects.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to test the feasibility and acceptability of a telephone-based psychosocial intervention for individuals undergoing treatment for HNC and to provide a preliminary assessment of intervention benefits. A mixed methods design was utilized in order to obtain a more complete understanding of participants’ experience. The EASE intervention was acceptable, feasible, and clinically relevant to HNC patients, and the project was able to successfully recruit newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients into the study. This is especially significant since other studies have reported difficulty recruiting this population for psychosocial interventions [39].

Despite our ability to successfully recruit HNC patients who were undergoing curative treatment, 33 % of participants did not complete the intervention. Although our findings suggest that there may be some demographic and medical variables that are associated with noncompletion (e.g., age, relationship status, and employment status), future psychosocial intervention studies need to consider innovative strategies to improve adherence to psychosocial and behavioral interventions.

The small sample size and the lack of a control group do not allow us to comment on the effectiveness of the intervention. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that the intervention may have helped to buffer the negative emotional and physical impact of cancer treatment. We postulate that distress reductions among participants are likely to be more than what we would expect in a usual care comparison group. Studies of HNC patients have reported increases in distress and decreases in quality of life at the end of treatment [39], suggesting that the modest decreases in cancer-specific distress that we observed may be meaningful. While large gains in psychosocial outcomes were not reported, all participants who completed the program displayed an increase in at least one desired outcome, with 81.8 % of participants increasing in at least two or more outcome domains.

Interestingly, participants reported a decrease in social support across the two time points. Although this is not what we had expected, a recent longitudinal study of HNC patients assessed at diagnosis and 12 months posttreatment described similar findings [40]. It is hypothesized that the high levels of physical and emotional distress in this population limit their ability to seek out social support [41]. Despite the observed decrease in social support scores, the quantitative findings suggest that the majority of participants appreciated the social support that they received through their participation in the EASE intervention. To illustrate, one participant stated, “I think the young lady listening to me, offering support, encouragement; you know just having someone you can talk to was a great thing.”

Special challenges and limitations

Head and neck cancer treatment is associated with a high number of treatment side effects and a subsequent decrease in quality of life [1–6]. HNC patients struggle to cope with the many challenges of treatment while attempting to manage the other aspects of their lives such as work responsibilities, family issues, and social relationships. EASE was developed with the goal of alleviating some of the stressors associated with cancer treatment. Unfortunately, many of the participants had difficulty finding the time to participate in regular counseling sessions because of competing demands and intrusive physical symptoms, such as fatigue and mouth and throat pain. This was evident in the counselors’ observation that participants were less engaged in the intervention during the middle and end phases of treatment, when many HNC patients experience an increase in the severity of their physical symptoms. Additionally, many of the participants were reticent to discuss intensely emotional issues during the telephone sessions. This reluctance may reflect the HNC patients’ perception that they did not have the emotional and physical resources to handle some of the strong emotions that may have been triggered by some of these discussions.

The small sample size and lack of a comparison group limit our ability to assess the impact of the EASE intervention on symptom management and overall quality of life. We postulate that the observed improvements in these participants are likely to be more than we would expect in a usual care comparison group given the documented decreases in quality of life observed in HNC patients undergoing treatment [4–6].

Implications and future directions

The EASE pilot intervention study demonstrated acceptability and feasibility of a psychosocial intervention aimed at improving symptom management and coping skills in newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients. Our lower than expected retention rate suggests that the EASE intervention did not satisfy the needs of all of these patients. Nevertheless, we were able to demonstrate that a proportion of HNC patients were able to successfully complete a psychosocial intervention while concurrently undergoing cancer treatment. The participants reported high levels of satisfaction with the program and high levels of self-efficacy regarding their ability to implement and utilize the skills that they had learned and practiced over the course of the program. Participants also provided feedback on the aspects of the EASE intervention that could be improved. Many noted that they would have preferred to begin the intervention sessions prior to the onset of treatment, and they would have appreciated the opportunity to meet their counselor face-to-face. Future interventions should consider including a face-to-face follow-up with patients who were not able to complete the phone intervention as well as a web-based resource for those who find that more convenient.

Although our small, single-group design limited our ability to interpret our psychosocial outcomes, the preliminary findings suggest that the intervention may have decreased cancer-specific distress during treatment. Future studies should carefully consider ways to integrate the counseling sessions into the cancer treatment continuum such that HNC patients receive adequate support during key phases of treatment (e.g., diagnosis, surgery, chemotherapy/radiation, and the reentry phase). These findings provide support for and inform design of future randomized trials to examine the efficacy of psychosocial interventions in newly diagnosed HNC patients.

References

Frampton M (2001) Psychological distress in patients with head and neck cancer: review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 39:67–70

Singh B (2001) Rehabilitation and quality of life assessment in head and neck cancer. In: Shah JP (ed) Cancer of the head and neck. BC Decker, Ontario

De Boer MF, Van den Borne B, Pruyn JF et al (1998) Psychosocial and physical correlates of survival and recurrence in patients with head and neck carcinoma: results of a 6-year longitudinal study. Cancer 83:2567–2579

Gritz ER, Carmack CL, de Moore C et al (1999) First year after head and neck cancer: quality of life. J Clin Oncol 17:352–360

Huguenin PU, Taussky D, Moe K et al (1999) Quality of life in patients cured from a carcinoma of the head and neck by radiotherapy: the importance of the target volume. Int J Radiot Oncol Biol Phys 45:47–52

Rogers SN, Lowe D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED (1999) The University of Washington head and neck cancer measure as a predictor of outcome following primary surgery for oral cancer. Head Neck 21:394–401

Kugaya A, Akechi T, Okuyama T et al (2000) Prevalence, predictive factors and screening for psychological distress in patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Cancer 88:2817–2823

Baile WF, Gilbertini M, Scott I et al (1992) Depression and tumor stage in cancer of the head and neck. Psycho-Oncology 1:15–24

Davies ADM, Davies C, Delpo MC (1986) Depression and anxiety in patients undergoing diagnostic investigations for head and neck cancers. Br J Psychiatry 149:491–493

Hammerlid E, Bjordal K, Ahlner-Elmoqvist M et al (2001) A prospective study of quality of life in head and neck cancer patients. Part I: at diagnosis. Laryngoscope 111:669–680

Breitbart W (1994) Psycho-oncology: depression, anxiety, delirium. Semin Oncol 21:754–769

Bolund C (1985) Suicide and cancer: II. Medical factors in suicide by cancer patients in Sweden 1973–1976. J Psychosoc Oncol 3:17–30

Bjordal K, Freng A, Thorvik J, Kaasa S (1995) Patients self-reported and clinician-rated quality of life in head and neck cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. Oral Oncol Eur J Cancer 31B:235–241

Morton RP, Izzard ME (2003) Quality of life outcomes in head and neck cancer patients. World J Surg 27:884–889

Mehanna HM, DeBoer MF, Morton RP (2008) The association of psycho-social factors and survival in head and neck cancer. Clin Otolaryngol 33:83–89

Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Ronis DI, Fowler KE, Terrell JE, Gruber SB, Duffy SA (2008) Quality of life scores predict survival among patients with head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:2754–2760

Hammerlid E, Ahlner-Elmoqvist M, Bjorklund A et al (1999) A prospective multi-center study in Sweden and Norway of mental distress and psychiatric morbidity in head and neck cancer patients. Br J Cancer 23:766–774

Hammerlid E, Persson LO, Sullivan M, Westin T (1999) Quality-of-life effects of psychosocial intervention in patients with head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 120:507–516

Petruson KM, Silander EM, Hammerlid EB (2003) Effects of psychosocial intervention on quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 25:576–584

Allison PJ, Edgar L, Nicolau B, Archer J, Black M, Hier M (2004) Results of a feasibility study for a psycho-educational intervention in head and neck cancer. Psycho-Oncology 13:482–485

Semple CJ, Dunwoody L, Kernohan WG (2009) Development and evaluation of a problem-focused psychosocial intervention for patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 17:379–388

Semple CJ, Sullivan K, Dunwoody L, Kernohan WG (2004) Psychosocial interventions for patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer Nurs 27:434–441

Semple CJ, Dunwoody L, Sullivan K, Kernohan WG (2006) Patients with head and neck cancer prefer individualized cognitive behavioral therapy. Eur J Cancer Care 15:220–227

Marcus AC, Garrett KM, Cella D et al (2004) Can telephone counseling post-treatment improve psychosocial outcomes among early stage breast cancer survivors? Psycho-Oncology 19:923–932

Garrett KM, Marcus AC, Brady M et al (2004) Can a telephone counseling intervention improve cancer-related quality of life and promote personal growth after the cancer experience: results from a randomized controlled trial. Poster presentation presented at Cancer Survivorship: Pathways to Health After Treatment, June 16–18, 2004, Washington DC

Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Tutty S, Ooperskalaski B, Von Koroff M (2004) Telephone psychotherapy and telephone care management for primary care patients starting antidepressant treatment: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc 292:935–942

Nelson EL, Wenzel LB, Osann K et al (2008) Stress, immunity, and cervical cancer: biobehavioral outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. Clin Cancer Res 14:1158–1178

Napolitano MA, Babyak MA, Palmer S et al (2002) Effects of a telephone-based psychosocial intervention for patients awaiting lung transplantation. Chest 122:1176–1184

Aronson JK (2000) Use of the telephone in psychotherapy. Book Mart Press, North Bergen

Gotay CC, Bottomley A (1998) Providing psychosocial support by telephone: what is its potential in cancer patients? Eur J Cancer Care 7:225–231

Marcus AC, Garrett KM, Kulchak-Rahm A, Barnes D, Dortch W, Juno S (2002) Telephone counseling in psychosocial oncology: a report from the cancer information and counseling line. Patient Educ and Couns 46:267–275

Creswell JW, Plano-Clark VL (2007) Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publishing Co, Thousand Oaks

US Department of Health and Human Services (1996) Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (1996). US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

Folkman S (1997) Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Soc Sci Med 45:1207–1221

Antoni MH (2003) Stress management intervention for women with breast cancer. American Psychological Association Press, Washington, DC

Penedo F, Molton I, Dahn JR, Shen B-J, Kinsinger D, Traeger L, Schneiderman N, Antoni M (2006) A randomized clinical trial of group-based cognitive-behavioral stress management in localized prostate cancer: development of stress management skills improves quality of life and benefit finding. Annals of Behav Med 31(3):261–270

QSR International Pty Ltd (2008) NVivo qualitative data analysis software version 8. QSR International Pty Ltd., Doncaster

Cohen J (1988) Statistical statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Hillsdale

Duffy SA, Ronis DL, Valenstein M, Lambert MT, Fowler KE, Gregory L et al (2006) A tailored smoking, alcohol, and depression intervention for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol, Biomark Prev 15:2203–2208

Derks W, De Leeuw R, Winnubust J, Hordijk GJ (2004) Elderly patients with head and neck cancer: physical, social and psychological aspects after one year. Acta Otolaryngol 124:509–514

Karnell LH, Christensen AJ, Rosenthal EL, Magnuson JS, Funk GF (2007) Influence of social support on health-related quality of life outcomes in head and neck cancer. Head and Neck 29:143–146

Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W (1979) Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med 41:209–218

Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G et al (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 11:570–579

Tait RC, Pollard CA, Margolis RB, Duckro PN, Krause SJ (1987) The pain disability index: psychometric and validity data. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 68:438–441

Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman H (1985) Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason, IG, Sarason BR (eds) Social support: Theory, research and application. The Hague, Holland

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health (National Cancer Institute, R-21; CA115354-01). The authors thank Jean Schleski, Kirsten Martin, and Dr. Carla Perry for their dedication and participation on this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kilbourn, K.M., Anderson, D., Costenaro, A. et al. Feasibility of EASE: a psychosocial program to improve symptom management in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 21, 191–200 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1510-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1510-z