Abstract

Purpose

Patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) experience significant symptom burden from combination chemotherapy and radiation (chemoradiation) that affects acute and long-term health-related quality of life (HRQOL). However, psychosocial impacts of HNC symptom burden are not well understood. This study examined psychosocial consequences of treatment-related symptom burden from the perspectives of survivors of HNC and HNC healthcare providers.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional, mixed-method study conducted at an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. Participants (N = 33) were survivors of HNC who completed a full course of chemoradiation (n = 20) and HNC healthcare providers (n = 13). Participants completed electronic surveys and semi-structured interviews.

Results

Survivors were M = 61 years old (SD = 9) and predominantly male (75%), White (90%), non-Hispanic (100%), and diagnosed with oropharynx cancer (70%). Providers were mostly female (62%), White (46%) or Asian (31%), and non-Hispanic (85%) and included physicians, registered nurses, an advanced practice nurse practitioner, a registered dietician, and a speech-language pathologist. Three qualitative themes emerged: (1) shock, shame, and self-consciousness, (2) diminished relationship satisfaction, and (3) lack of confidence at work. A subset of survivors (20%) reported clinically low social wellbeing, and more than one-third of survivors (35%) reported clinically significant fatigue, depression, anxiety, and cognitive dysfunction.

Conclusion

Survivors of HNC and HNC providers described how treatment-related symptom burden impacts psychosocial identity processes related to body image, patient-caregiver relationships, and professional work. Results can inform the development of supportive interventions to assist survivors and caregivers with navigating the psychosocial challenges of HNC treatment and survivorship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Head and neck cancers (HNCs; e.g., cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx) will account for more than 70,000 new cancer diagnoses and more than 16,000 deaths in the United States in 2024 alone [1]. For most HNCs, the location of tumors can interfere with vital functions including breathing, swallowing, and speaking, and patients experience significant disease-related symptom burden. Patients with locally advanced HNC are often treated with combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy (chemoradiation), which can be arduous. Treatment-related xerostomia, sticky saliva, fatigue, altered appearance, and impairments in speech, taste, smell, swallowing, and sexual functioning contribute to even greater symptom burden and have a tremendous impact on patients’ acute and long-term health-related quality of life (HRQOL), or overall wellbeing [2,3,4,5]. In addition, persistent side effects and impairments after treatment can affect survivors’ overall mental health [6], body image [7], intimate relationships and sexual health [8], and ability to return to work [9].

However, a limitation of past research in HNC is that most conclusions about how treatment-related symptom burden affects HRQOL are based on quantitative data with little attention to survivors’ lived experiences. Data collected via qualitative methods (e.g., semi-structured interviews) can provide insights into the contexts, psychosocial complexities, and meaning-making processes of survivorship that cannot be understood through quantitative data alone. To address this knowledge gap, our team conducted a mixed-method study incorporating qualitative interviews and quantitative surveys to investigate survivors of HNC’s experiences of symptom burden after chemoradiation treatment and to explore the consequences of symptom burden on aspects of survivors’ HRQOL related to psychosocial functioning and wellbeing. Provider stakeholders were also interviewed to gain multiple perspectives.

Methods

Participants and procedures

This article reports on a portion of findings from a larger study investigating HRQOL among survivors of locally advanced HNC [10, 11]. The protocol was reviewed by Advarra Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt from oversight due to minimal risk (Pro00045231). Eligible survivors of HNC were (1) ≥ 18 years old; (2) diagnosed with locally advanced HNC; (3) finished chemotherapy (minimum three weekly doses or one bolus dose) and radiation therapy (minimum six weeks) within the past year; (4) expected to survive ≥ 3 months; (5) able to speak and read English; and (6) able to provide informed consent. Individuals with pre-existing conditions that could preclude participation were excluded (e.g., dementia). HNC providers were clinical team members that worked with HNC patients (e.g., physicians, nurses), excluding trainees and fellows.

From September 2020 to January 2021, a trained study coordinator worked with staff in Moffitt Cancer Center’s Head and Neck-Endocrine Oncology Clinic to identify potentially eligible survivors of HNC. The coordinator approached survivors by telephone or in-person to provide information about the study, confirm eligibility, and determine interest in participation. Providers were recruited from Moffitt Cancer Center’s Head and Neck-Endocrine Oncology Clinic via email. Participants provided verbal consent, completed an individual semi-structured interview from their home or office via telephone or videoconference, and completed surveys via REDCap. Survivors were compensated with a $50 gift card. Providers were not compensated.

Participants were continuously recruited and interviewed until no additional themes emerged with subsequent interviews (i.e., thematic saturation was reached) based on interviewer feedback. Twelve interviews are typically sufficient for saturation [12]. The data that support this study’s findings are not publicly available, as they contain information that could compromise participant privacy.

Semi-structured interviews

Two study team members trained in qualitative interviewing conducted individual interviews with participants using semi-structured guides containing a list of questions and exploratory probes (Supplemental Appendix 1 and 2). Interviews with survivors focused on their lived experiences of symptom burden and the impact of HNC symptom burden on various aspects of their lives. Interviews with providers focused on their experiences providing care for patients with HNC and common side effects patients experience based on their observations and clinical expertise. Other topics explored in the semi-structured interviews have been previously reported (e.g., behavioral intervention preferences, experiences during COVID-19) [10, 11]. To facilitate discussions about symptom burden, participants were shown the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) item library of 78 patient-reported adverse events derived from the CTCAE [13]. The team met regularly during data collection to evaluate the quality of data collected, assess the effectiveness of the interview guide, discuss emerging themes, and track data saturation. All interviews were audio recorded.

Survey measures

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Survivors self-reported their demographics and clinical characteristics (e.g., date of diagnosis, treatments received). Providers self-reported their demographics and credentials.

HRQOL

The 39-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Head and Neck Cancer (FACT-HN) assessed overall HRQOL and five subscales: physical wellbeing, social wellbeing, emotional wellbeing, functional wellbeing, and a HNC subscale [14]. Survivors rated the degree to which items applied to them in the past week on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Scores on the wellbeing subscales were summed to derive an overall HRQOL score, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 108. Higher scores indicated better HRQOL. The following scores were considered clinically low: overall HRQOL ≤ 62, physical wellbeing ≤ 15, social wellbeing ≤ 16, emotional wellbeing ≤ 13, and functional wellbeing ≤ 11 [15].

Body image distress

The 21-item FACT/McGill Body Image Scale-Head and Neck (FACT/MBIS) assessed body image in the past 2 weeks across two subscales: negative self-image and social discomfort [16]. Survivors rated their agreement with items on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Items within each subscale were summed, with possible scores ranging from 0–44 (negative self-image) and 0–40 (social discomfort). Higher scores indicated more distress.

Fatigue

The 13-item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT)-Fatigue scale assessed fatigue in the past week [17]. Survivors rated the degree to which items applied to them on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Items were summed to produce a total score, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 52. Lower scores indicated worse fatigue, and scores ≤ 30 indicated clinically significant fatigue [18, 19].

Depression, anxiety, and cognitive function

Depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, and cognitive function were assessed with relevant 4-item Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) short forms [20, 21]. Survivors rated the frequency of symptoms in the past week on 5-point Likert-type scales from 1 (never) to 5 (always or very often/several times a day). Standardized T-scores were calculated for each construct (normative M = 50, SD = 10). Higher scores indicated worse depressive and anxious symptoms, and lower scores indicated worse cognitive dysfunction. Scores ≥ 55 indicated at least mild depressive and anxious symptoms [22, 23], whereas scores ≤ 44 indicated at least mild cognitive dysfunction [24].

Analyses

Participant characteristics and quantitative outcomes were described with summary statistics using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC). The proportion of survivors that exceeded known clinical thresholds for the quantitative outcomes were also calculated. Two study team members (CG, BA) with graduate-level training and extensive experience in qualitative methods led the analysis of interview data. Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim using NVivo’s artificial intelligence-assisted software and analyzed for qualitative themes using NVivo 12 Plus software. Analyses were guided by tenets of applied thematic analysis [25]. In a stepwise process, the coders read the interview transcripts, recorded their initial impressions, and developed a preliminary codebook that included a priori codes and definitions. The codebook was refined through multiple rounds of reiterative coding, and the coders achieved acceptable intercoder reliability (Cohen’s Kappa = 0.80). They subsequently conducted two rounds of line-by-line coding for all transcripts, and emergent codes and subcodes were inductively identified. Coding discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Finally, coded data were organized into primary and secondary themes, and representative quotes were identified. COREQ qualitative guidelines were used to inform comprehensive reporting of the qualitative components of this study [26]. Quantitative and qualitative data were triangulated to compare findings, with qualitative interviews providing context and illustrations of meaningful impacts on survivors’ HRQOL.

Results

Participant characteristics

As previously reported [10, 11], our sample (N = 33) included 20 survivors of HNC and 13 HNC providers (Table 1). Survivors were an average of 61 years old and predominantly male (75%), White (90%), and non-Hispanic (100%). Most were diagnosed with oropharynx cancer (70%), and most had human papillomavirus positive (HPV +) disease (70%). On average, survivors had been diagnosed with HNC 9 months prior to study enrollment and had completed treatment 6 months prior. HNC providers were mostly female (62%), White (46%) or Asian (31%), and non-Hispanic (85%) and included physicians (54%), registered nurses (23%), an advanced practice nurse practitioner, a registered dietician, and a speech-language pathologist (8% each).

Quantitative surveys

Table 2 shows average scores for each survey completed by survivors as well as the proportion of survivors exceeding known clinical cut-offs. For all surveys with known clinical cut-offs, average scores were within normal limits. However, subsets of survivors reported clinically low overall HRQOL (15%), physical wellbeing (5%), social wellbeing (20%), emotional wellbeing (5%), and functional wellbeing (10%). In addition, 35% of survivors reported at least mild fatigue, depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, and cognitive dysfunction.

Qualitative themes

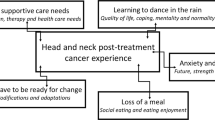

The semi-structured interviews ranged from 39–149 min for survivors and 29–60 min for providers. Three themes emerged from interviews with survivors and providers related to psychosocial challenges of HNC symptom burden: (1) shock, shame, and self-consciousness, (2) diminished partnership satisfaction, and (3) lack of confidence at work. Table 3 includes exemplar quotes for each theme.

“Who the heck is that?”: shock, shame, and self-consciousness

Weight and muscle loss were common experiences that negatively affected survivors’ body image and increased their awareness of how they were viewed by others. Some survivors described feeling disturbed watching themselves slowly “waste away” or not recognizing their own reflection. Changes in appearance and physical ability affected how survivors understood their sense of self, and many described difficulties coming to terms with new impairments. For example, survivors who were very active or athletic prior to HNC treatment described how loss of athleticism and independence were physically, emotionally, and psychologically challenging. HNC survivors also described concern with the ways others viewed their post-treatment bodies. Survivors with observable physical changes and side effects, such as those who experienced lymphoedema, described self-consciousness in public. HNC providers echoed these concerns, observing how survivors of HNC report feeling “ashamed” or “embarrassed” about physical changes and difficulty eating, causing them to avoid public interactions.

“It’s frustrating on both sides”: diminished partnership satisfaction

Survivors described how many HNC treatment–related side effects, such as fatigue, mouth sores, pain, difficulty swallowing, taste changes, and mood changes (e.g., increased irritability), affected their personal relationships, most often with caregivers. As side effects worsened near the end of treatment, survivors described having little interest engaging or communicating with others and instead found it easiest to “just exist.” HNC providers also described how symptom burden can impact survivors’ closest relationships, noting how HNC-related challenges can make “a good relationship better, and a bad relationship worse.” Oral and gastrointestinal side effects (e.g., dry mouth, mouth sores, loss of taste and appetite) were described as some of the most socially challenging side effects that heightened frustration and tension in caregiver/partner relationships. Some survivors reported how their symptom burden left them largely uninterested in sexual intimacy or affection, particularly during and soon after treatment. They described not paying “too much attention to that” when “you’re on death’s edge.”

“I’m not the person I was”: lack of confidence at work

Most survivors described difficulties returning to work after HNC treatment, in large part due to ongoing symptom burden. Fatigue was described as the most significant side effect affecting return to work, in addition to dry mouth, nausea, cognitive dysfunctions (e.g., memory loss, difficulty concentrating), hearing loss, skin irritation, and frequent urination. Most survivors of HNC in this study were employed in professional roles that rely on interpersonal communication (e.g., meetings, presentations), and they described how their symptom burden interfered with their ability to successfully communicate with others. In turn, this contributed to more anxiety and less confidence in the workplace, despite their professional qualifications and experience. However, survivors in professional roles had more flexibility and support to continue working, whereas survivors with physically demanding jobs described having fewer resources to help them navigate the challenges of returning to work. Providers, however, observed a varied impact on professional work, with some survivors able to work throughout treatment and others unable to continue working at all. One provider described how survivors can experience frustration and role conflict by feeling like they are not productive enough at work while simultaneously feeling unable to properly manage their symptoms, which providers described as “a full-time job” in itself.

Discussion

This mixed-method study interpretively examined relationships between HNC-related symptom burden and psychosocial functioning using semi-structured qualitative interviews with survivors of HNC and HNC providers and validated survey measures, with a particular focus on the contexts and complexities of survivors’ lived experiences. This study adds to ongoing conversations focused on interactional challenges of relationships and identity, and findings illuminate how acute and lasting HNC symptom burden inform a “loss of self” [27], in which former positive understandings of self are no longer available and there are a lack of new positive self-images.

A key finding was that changes to body image were common and distressing. Survivors and providers described how physical changes after HNC treatment can lead to shock, shame, and embarrassment when navigating public spaces. Survivors described difficulty coping with discomfort about how others view them as well as challenges related to how they view themselves. This complements previous research that found survivors of HNC can be shocked by their altered appearance post-treatment and unable to recognize themselves in the mirror [28], known as “mirror trauma” [29]. We also quantitatively assessed body image using the FACT/MBIS, which was specifically developed for survivors of HNC [16]. Given the recent development of the FACT/MBIS, there are limited studies we can use as benchmarks to contextualize the scores in our sample. However, average scores in our sample were within the top decile of possible scores for the negative self-image subscale, social discomfort subscale, and total score, indicating that body image concerns were prevalent.

We also found that symptom burden can negatively impact survivors’ close relationships, particularly with their caregiver partners. Participants described how HNC-related symptom burden can cause survivors to withdraw or disengage from close relationships and introduce new tensions, a phenomenon that has been documented in existing literature [30,31,32]. Survivors and providers offered salient insights into the complex interactional challenges surrounding food. For survivors, taste changes and difficulty swallowing can make it challenging or impossible to eat previously comforting foods. While caregivers were not interviewed in this study, survivors and providers described how caregivers experience feelings of frustration and helplessness when attempting to provide nutritious, comforting foods to their loved ones. These dynamics can further add to negative feelings for survivors (e.g., guilt, being a “burden”). These findings are similar to previous research from Badr and colleagues [33] that showed how tension related to eating can cause patients with HNC and caregivers to “snap” at one another. Unsurprisingly, of the various wellbeing domains assessed by the FACT-HN, the highest proportion of survivors reported clinically low social wellbeing (20%).

Our findings also demonstrate how symptom burden can disrupt a professional sense of self. Work is an important part of everyday life, and being unable to work can compromise one’s identity and social life, which can lead to social isolation and diminished HRQOL [34, 35]. We extended past work by showing how work interruptions can also affect one’s understanding of other identity categories. For example, with the inability to do physically demanding or outdoor work, survivors of HNC in manual labor positions are particularly vulnerable to job loss, which can impact their ability to meet other obligations (e.g., the “family provider”). This complements studies showing that survivors of HNC experience significant financial toxicity (e.g., financial burden/costs and subjective financial distress) [36], with more than 50% of survivors unable to return to work post-HNC treatment [37]. Survivors in this study described how fatigue and cognitive dysfunction, among other side effects, interfere with work-related confidence. Notably, clinically significant levels of fatigue and cognitive dysfunction were reported by more than one-third of survivors. Moreover, the interference of symptom burden on survivors’ ability to work contributed to greater feelings of depression and anxiety, and more than one-third of survivors in our sample reported clinically significant symptoms of depression and anxiety as well.

Notably, relatively small proportions of survivors in this sample reported clinically low HRQOL (15%), physical wellbeing (5%), emotional wellbeing (5%), and functional wellbeing (10%) on the survey measures. Yet, this was not reflected in the qualitative data, as survivors described many challenges across these domains. This discrepancy indicates that quantitative surveys alone may not capture the full picture of how HNC symptom burden affects survivors’ HRQOL, and it further underscores the value of incorporating qualitative data into mixed-method studies to gain a more comprehensive understanding of survivors’ lived experiences.

Limitations

This study included a small sample of survivors of HNC who were mostly White, non-Hispanic, and male. Most were diagnosed with oropharynx cancer, most had HPV + disease, all were treated with chemoradiation, and only two participants received trimodality treatment (i.e., surgery). Thus, findings may not generalize to more diverse HNC populations who undergo different treatments. Moreover, average time since treatment completion was approximately 6 months. Future work should explore the qualitative themes in this study among more diverse samples of survivors and at other times in the HNC survivorship trajectory (e.g., 1–2 years into survivorship, as physical symptom burden has improved). As most existing literature on relationship impacts examines the experiences of heterosexual married couples, perspectives of individuals identifying as sexual and gender minorities will be particularly important to more comprehensively understand the effects of HNC on relationships, embodiment, and identity.

Clinical implications

Findings from this study have important implications for the development of supportive care interventions to improve HRQOL among survivors of HNC. Supportive care interventions should include education about how HNC treatment and subsequent symptom burden may alter survivors’ appearance as well as support for understanding complex changes to personal identity. Educational support for survivors of HNC and their caregivers is also needed related to nutrition and eating post-treatment. Ongoing relationship support may also be an important component of improving survivorship. Finally, there is a need to further understand identity dilemmas among survivors of HNC and the practical consequences related to everyday challenges. Group support may be an appropriate method of helping survivors make sense of new realities and creating opportunities for sharing management strategies with their peers.

Conclusions

This mixed-method study investigated the psychosocial consequences of symptom burden related to HNC chemoradiation treatment. Findings revealed that survivors of HNC experienced major challenges in navigating social life, including identity disruptions in relation to body image, intimate relationships, and professional work. Future studies should examine how survivors of HNC reconcile and make sense of a loss of self and explore the perspectives of caregivers. Findings may inform the development of supportive interventions for survivors of HNC as they navigate survivorship.

Data availability

The data that support this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

References

American Cancer Society (2024) Cancer facts & figures 2024. Atlanta: Am Cancer Soc

Machtay M, Moughan J, Trotti A et al (2008) Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: an RTOG analysis. J Clin Oncol 26(21):3582–3589. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8841

Langendijk JA, Doornaert P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Leemans CR, Aaronson NK, Slotman BJ (2008) Impact of late treatment-related toxicity on quality of life among patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 26(22):3770–3776. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6647

Rathod S, Livergant J, Klein J, Witterick I, Ringash J (2015) A systematic review of quality of life in head and neck cancer treated with surgery with or without adjuvant treatment. Oral Oncol 51(10):888–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.07.002

Dunne S, Mooney O, Coffey L et al (2017) Psychological variables associated with quality of life following primary treatment for head and neck cancer: a systematic review of the literature from 2004 to 2015. Psychooncology 26(2):149–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4109

Neilson KA, Pollard AC, Boonzaier AM et al (2010) Psychological distress (depression and anxiety) in people with head and neck cancers. Med J Aust 193:S48–S51

Covrig VI, Lazăr DE, Costan VV, Postolică R, Ioan BG (2021) The psychosocial role of body image in the quality of life of head and neck cancer patients. what does the future hold?—A review of the literature. Medicina 57(10):1078

Low C, Fullarton M, Parkinson E et al (2009) Issues of intimacy and sexual dysfunction following major head and neck cancer treatment. Oral Oncol 45(10):898–903

Yu J, Smith J, Marwah R, Edkins O (2022) Return to work in patients with head and neck cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck 44(12):2904–2924

Kirtane K, Geiss C, Arredondo B et al (2022) “I have cancer during COVID; that’sa special category”: a qualitative study of head and neck cancer patient and provider experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer 30(5):4337–4344

Oswald LB, Arredondo B, Geiss C et al (2022) Considerations for developing supportive care interventions for survivors of head and neck cancer: a qualitative study. Psychooncology 31(9):1519–1526

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006) How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method 18(1):59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x05279903

Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA et al (2015) Validity and reliability of the US National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). JAMA Oncol 1(8):1051–1059

List MA, D’Antonio LL, Cella DF et al (1996) The performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients and the functional assessment of cancer therapy-head and neck scale. A study of utility and validity. Cancer. 77(11):2294–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11%3c2294::AID-CNCR17%3e3.0.CO;2-S

Pearman T, Yanez B, Peipert J, Wortman K, Beaumont J, Cella D (2014) Ambulatory cancer and US general population reference values and cutoff scores for the functional assessment of cancer therapy. Cancer 120(18):2902–2909. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28758

Rodriguez AM, Frenkiel S, Desroches J et al (2019) Development and validation of the McGill body image concerns scale for use in head and neck oncology (MBIS-HNC): a mixed-methods approach. Psychooncology 28(1):116–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4918

Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E (1997) Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage 13(2):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6

Eek D, Ivanescu C, Corredoira L, Meyers O, Cella D (2021) Content validity and psychometric evaluation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue scale in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Patient Rep Outcomes 5(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-021-00294-1

Piper BF, Cella D (2010) Cancer-related fatigue: definitions and clinical subtypes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 8(8):958–966. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2010.0070

Schalet BD, Pilkonis PA, Yu L et al (2016) Clinical validity of PROMIS depression, anxiety, and anger across diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol 73:119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.036

Cella D, Choi SW, Condon DM et al (2019) PROMIS(®) Adult health profiles: efficient short-form measures of seven health domains. Value Health 22(5):537–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.02.004

Kroenke K, Stump TE, Chen CX et al (2020) Minimally important differences and severity thresholds are estimated for the PROMIS depression scales from three randomized clinical trials. J Affect Disord 266:100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.101

Cella D, Choi S, Garcia S et al (2014) Setting standards for severity of common symptoms in oncology using the PROMIS item banks and expert judgment. Qual Life Res 23(10):2651–2661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0732-6

Rothrock NE, Cook KF, O’Connor M, Cella D, Smith AW, Yount SE (2019) Establishing clinically-relevant terms and severity thresholds for Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® (PROMIS®) measures of physical function, cognitive function, and sleep disturbance in people with cancer using standard setting. Quality of Life Research 28(12):3355–3362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02261-2

Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE (2011) Applied thematic analysis. sage publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384436

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357

Charmaz K (1983) Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn 5(2):168–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512

Gibson C, O’Connor M, White R, Jackson M, Baxi S, Halkett GK (2021) ‘I didn’t even recognise myself’: survivors’ experiences of altered appearance and body image distress during and after treatment for head and neck cancer. Cancers 13(15):3893. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13153893

Freysteinson WM (2020) Demystifying the mirror taboo: a neurocognitive model of viewing self in the mirror. Nurs Inq 27(4):e12351

Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G (2005) A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med 60(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.018

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Wyse R, Hobbs KM, Wain G (2007) Life after cancer: couples’ and partners’ psychological adjustment and supportive care needs. Support Care Cancer 15(4):405–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0148-0

Johnson HA, Zabriskie RB, Hill B (2006) The contribution of couple leisure involvement, leisure time, and leisure satisfaction to marital satisfaction. Marriage Fam Rev 40(1):69–91

Badr H, Herbert K, Reckson B, Rainey H, Sallam A, Gupta V (2016) Unmet needs and relationship challenges of head and neck cancer patients and their spouses. J Psychosoc Oncol 34(4):336–346

Isaksson J, Wilms T, Laurell G, Fransson P, Ehrsson YT (2016) Meaning of work and the process of returning after head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 24:205–213

Rasmussen DM, Elverdam B (2008) The meaning of work and working life after cancer: an interview study. Psychooncology 17(12):1232–1238

Nguyen OT, Donato U, McCormick R et al (2023) Financial toxicity among head and neck cancer patients and their caregivers: a cross-sectional pilot study. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 8(2):450–457

Rosi-Schumacher M, Patel S, Phan C, Goyal N (2023) Understanding financial toxicity in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Clinical Medicine Insights: Oncology 17:11795549221147730

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Kelsey Scheel for her support conducting this study and the survivors and providers who participated.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a Moffitt Cancer Center Innovation Award (MPIs: Oswald, Kirtane), Moffitt’s Participant Research, Interventions, and Measurement (PRISM) Core, and a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA076292).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: CG, AH, KK, LO; Formal analysis: CG, AH, BA, LO; Investigation: CB, LO; Resources: CC, KP, KK; Data curation: CG, AH, BA; Supervision: BH, HJ, KK, LO; Project administration: YR; Funding acquisition: KK, LO; Writing - original draft: CG, AH, KK, LO; Writing - review & editing: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Chung receives honoraria from Sanofi and Exelexis for ad hoc Scientific Advisory Board participation. Dr. Gonzalez is a paid consultant for SureMed compliance and KemPharm, and an advisory board member for Elly Health, Inc outside of this work. Dr. Jim is a paid consultant for RedHill BioParma, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck and has grant funding from Kite Pharma outside of this work. Dr. Kirtane owns stock in Seattle Genetics, Oncternal Therapeutics, and Veru. The other authors have no other relevant competing interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

The current research was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Advarra and determined to be exempt from oversight due to minimal risk (Pro00045231). All aspects of this study were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and later amendments.

Consent to participate

All participants provided verbal consent prior to study enrollment.

Consent for publication

Participants provided verbal consent to have de-identified data published.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Chung receives honoraria from Sanofi and Exelixis for ad hoc scientific advisory board participation. Dr. Gonzalez is a paid consultant for Sure Med Compliance and KemPharm, and an advisory board member for Elly Health, Inc., outside of this work. Dr. Jim is a paid consultant for RedHill Biopharma, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck and has grant funding from Kite Pharma outside of this work. Dr. Kirtane owns stock in Seattle Genetics, Oncternal Therapeutics, and Veru. The other authors have no other relevant competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Geiss, C., Hoogland, A.I., Arredondo, B. et al. Psychosocial consequences of head and neck cancer symptom burden after chemoradiation: a mixed-method study. Support Care Cancer 32, 254 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08424-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08424-3