Abstract

Background

Currently, there’s not a well-accepted optimal approach for umbilical hernia repair in patients with obesity when comparing laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair (LUHR) versus open umbilical hernia repair (OUHR).

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate if there’s a difference in postoperative complications after LUHR versus OUHR with the goal of indicating an optimal approach.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was completed using the 2016 National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database to identify patients with obesity (Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2) who underwent LUHR or OUHR. Patients were divided into OUHR and LUHR groups, and post-operative outcomes were compared, focusing on wound complications.

Results

A total of 12,026 patients with obesity who underwent umbilical hernia repair were identified; 9695 underwent OUHR, while 2331 underwent LUHR. The LUHR group was found to have a statistically significant higher BMI (37.5 kg/m2 vs. 36.1 kg/m2; p < 0.01) and higher incidence of diabetes mellitus requiring therapy (18.4% vs. 15.8%; p < 0.01), hypertension (47.5% vs. 43.8%; p < 0.01), and current smoker status (18.6% vs. 16.5%; p < 0.02). Superficial surgical site infection (SSI) was significantly higher in the OUHR group (1.5% vs. 0.9%; p < 0.03), and there was a trend towards higher deep SSI in the OUHR group (0.3% vs. 0.5%; p = 0.147). There was no difference in organ space SSI, wound disruption, or return to OR. On logistic regression, composite SSI rate (defined as superficial, deep, and organ space SSIs) was significantly increased in the OUHR group (p < 0.01). Predictive factors significantly associated with increased morbidity included female gender and higher BMI.

Conclusions

In patients with obesity, even though the LUHR group had an overall higher BMI and higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, and current smoking status, they experienced decreased post-operative wound complications compared to the OUHR group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Umbilical hernias are present in up to 2% of the adult population and the repair of umbilical hernias compromise 10% of all hernia repairs in the USA annually [1]. With the increasing prevalence of obesity, defined as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, in our culture to 39.6%, more umbilical hernia repairs are being performed on patients with obesity [2, 3]. There is currently not a well-accepted optimal procedure for umbilical hernia repair in patients with obesity when comparing LUHR and OUHR.

Obesity is associated with a higher risk of primary and incisional hernia development, including umbilical hernias [4,5,6,7]. Factors related to obesity that contribute to the increased risk of hernia formation include increased intra-abdominal pressure, increased abdominal circumference, increased visceral fat, and higher risk of surgical site infection (SSI) following abdominal surgery [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Patients with obesity are also at a higher risk of SSI, seroma formation, and other wound complications after hernia repair compared to the non-obese population [3]. In addition to obesity, smoking and diabetes mellitus are also associated with a high risk of wound complications after abdominal surgery [16, 17].

With the increased prevalence of obesity and the increased wound complications known to be associated with obesity, surgeons are facing the challenge of trying to improve wound outcomes in patients with obesity after hernia repair. LUHR has been shown in the literature to be associated with fewer post-operative complications including wound morbidity and ileus compared to OUHR in the general population [18,19,20,21]. A Cochrane review in 2011 showed no difference in recurrence rates between laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repair, and laparoscopic repair conferred a 4-fold decrease in the risk of wound infections [22]. A retrospective chart review suggested that LUHR in patients with obesity is associated with lower rates of post-operative infection; however, it was a single institution study from 2003 to 2009 [23].

There are several studies comparing LUHR and OUHR in the general population; however the most recent study based on NSQIP data looked at the years 2009 and 2010 [20, 24,25,26]. Another retrospective review of NSQIP data from 2009 to 2012 showed that patients with obesity had lower rates of wound infection after laparoscopic compared to open ventral hernia repair [27]. Since 2012, there has been lack of data that compares LUHR to OUHR specifically in patients with obesity. With advancements in laparoscopic techniques and training, as well as with the increasing rates of obesity in our country, it is important to continue to evaluate the optimal approach for umbilical hernia repair in this patient population. The objective of this study was to compare the rate of post-operative complications after laparoscopic versus open umbilical hernia repair in patients with obesity, with the goal of indicating an optimal approach.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective cohort study using the Participant Use Files of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database from January 1, 2016 to December 31, 2016. The NSQIP database consists of prospectively collected data looking at 30-day surgical outcomes in approximately 700 hospitals. The data collected included patient risk factors, operative variables, and post-operative mortality and morbidity for 30 days post-operatively for both inpatient and outpatient operations. The data are collected by trained Surgical Clinical Reviewers at individual hospitals and are entered online into the database. The outcomes are then shared with hospitals in a blinded, risk-adjusted format to use for comparing individual hospital complication rates and outcomes to national rates.

Institutional review board approval was obtained. Written informed consent was not necessary as this was a retrospective NSQIP review.

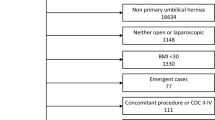

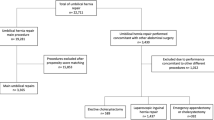

Inclusion criteria included patients 18 years of age and older with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 who underwent umbilical hernia repairs in 2016. Exclusion criteria included patients < 18 years of age and BMI < 30 kg/m2. CPT codes 49585 and 49587 were used to identify patients undergoing open umbilical hernia repair, and codes 49652 and 49653 were used to identify all laparoscopic ventral hernia repairs. However, since the laparoscopic codes do not differentiate between umbilical hernias and other ventral hernias, the ICD 9/10 codes were used to identify the diagnosis of umbilical hernia repair, including 552.x, 553.x, K42.0, and K42.9. Only patients who had both the appropriate CPT code and diagnosis code were included in the study. There was no method to distinguish between primary umbilical hernia and incisional umbilical hernia if the diagnosis was coded as umbilical hernia.

Patient demographics and comorbidities were examined including age, sex, BMI, diabetes status, smoking status, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) status, pre-operative wound infection status, recent weight loss, ASA classification, hypertension (HTN) requiring medication, and steroid use. Operative details including laparoscopic versus open technique, elective versus emergent status, anesthesia type and inpatient versus outpatient procedure status were also assessed. Primary outcomes were superficial surgical site infection, deep surgical site infection, surgical organ space infection, wound disruption, operative time, length of stay, and return to operating room.

Descriptive statistics were used to determine trends in our patient population and to describe our data. Continuous variables were reported as mean (± SD) and categorical variables were reported as frequency (%). Categorical outcomes were compared using Pearson’s Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous outcomes were compared using between-group analysis of variance (ANOVA). Binary logistic regression analysis was used to adjust for potential confounders. Individual Cochran–Armitage tests and Independent Samples Kruskal–Wallace tests were used to determine if trends were present in outcomes and operative times by BMI for LUHR versus OUHR.

Results

A total of 12,026 patients with obesity who underwent umbilical hernia repair were identified. 9695 (80.6%) patients underwent OUHR, while 2331 (19.4%) patients underwent LUHR. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are provided in Table 1. Age, COPD status, and chronic steroid use were similar between the OUHR and LUHR groups. The LUHR group was found to have a statistically significant higher BMI (37.5 vs. 36.1; p < 0.01) and higher incidence of diabetes mellitus requiring therapy (18.4% vs. 15.8%; p < 0.01), hypertension (47.5% vs. 43.8%; p < 0.01), and current smoker status (18.6% vs. 16.5%; p < 0.02). More men underwent OUHR (81.2% men vs. 77.5% women; p < 0.01), while more women underwent LUHR (22.5% women vs. 18.3% men; p < 0.01).

Comparisons for all complications are reported between the two groups, LUHR and OUHR, in Table 2. Complications examined include superficial SSI, deep SSI, organ space SSI, wound disruption, pneumonia, urinary tract infection (UTI), operative time, and return to the operating room. Operative time was significantly longer in the LUHR group (70 vs. 44 min; p < 0.01). Superficial surgical site infection (SSI) was statistically significantly higher in the OUHR group (1.5% vs. 0.9%; p < 0.03), and there was a trend towards higher deep SSI in the OUHR group (0.3% vs. 0.1%; p = 0.147). There was a statistically significant higher rate of post-operative pneumonia in the LUHR group (0.4% vs. 0.1%; p = 0.012); however this was only significant in the non-elective group on crosstab with elective versus non-elective surgery. There was no difference in organ space SSI, wound disruption, UTI, or return to the operating room.

Logistic regression was utilized and revealed that composite SSI, defined as superficial, deep and organ space SSIs, was significantly increased in the OUHR group (1.9% vs. 1.1%; p < 0.01); shown in Table 2. Logistic regression analysis, using the baseline characteristics as independent variables, was utilized to determine if any of the baseline characteristics were acting as confounding variables; shown in Table 3. Composite SSI was found to be statistically significantly higher in the OUHR group for female patients, for non-elective surgeries, and in patients with a higher BMI.

Composite SSI was found to be statistically significantly higher for non-elective surgery compared to elective surgery when looking at both LUHR and OUHR. When broken down into superficial SSI, deep SSI and organ space SSI, only superficial SSI was statistically significantly higher for the non-elective surgery group (p < 0.001). OUHR in a non-elective setting was associated with a higher rate of superficial SSI compared to an elective setting (p < 0.001); however, there was no significant difference in superficial SSI rates between non-elective LUHR and elective LUHR (p = 0.181).

Individual Cochran–Armitage tests were used to determine if a trend is present in the distribution of outcomes by BMI for LUHR versus OUHR as shown in Table 4. The Independent Samples Kruskal–Wallis Test was used to determine if a trend was present in the distribution of operative times by BMI for LUHR versus OUHR. In the OUHR group, as obesity class increased, increases were found for superficial SSI (0.9% vs. 1.4% vs. 3.3%; p < 0.001), deep SSI (0.1% vs. 0.2% vs. 0.8%; p < 0.001), return to operating room (0.5% vs. 0.8% vs. 1.1%; p = 0.041), post-operative pneumonia rates (0.1% vs. 0.1% vs. 0.3%; p = 0.018), and composite SSI (1.2% vs. 1.8% vs. 4.2%; p < 0.001). Operative time also increased as obesity class increased, in both OUHR (34 vs. 37 vs. 44 min; p < 0.001) and LUHR (57 vs. 60 vs. 67 min; p < 0.001) groups.

Discussion

This study examined the short-term post-operative outcomes after LUHR and OUHR in patients with obesity using the NSQIP database. Our results found that LUHR was associated with a decreased risk of wound morbidity.

Similar results have been reported in the literature. Colon et al. performed a retrospective review from a single institution comparing LUHR versus OUHR in patients with obesity. They found a lower wound-related and overall complication rate as well as a lower rate of hernia recurrence in the LUHR group as compared to the OUHR group [23]. This study was limited by the small sample size of 123 patients. Cassie et al. performed a large retrospective cohort study using the NSQIP database during 2009–2010 to compare LUHR and OUHR in the obese population and found that LUHR was associated with decreased wound complications. The average BMI in the LUHR group was 34.3 kg/m2 versus 31.7 kg/m2 in the OUHR group, showing a possible selection bias toward laparoscopic repair in the obese population [20]. Regner et al. found a decreased rate of surgical site complications with laparoscopic ventral hernia repair compared to open ventral hernia repair in the obese population using the NSQIP data from 2009 to 2012 [27]. Laparoscopic hernia repair’s reduced wound complication rates may be due to small incision size and less contact of the mesh with the skin.

As with previous studies, the majority of repairs in our study were performed in an open fashion (80.6% open vs. 19.4% laparoscopic). However, compared to the Cassie et al. paper, the proportion of laparoscopic repair has appreciably increased from 11.5% LUHR in the Cassie et al. study to 19.4% LUHR in our current study [20]. This could reflect a change in practice based on the previous literature that LUHR is associated with decreased wound complications in the obese population [20, 22, 23, 27, 28]. This could also represent the increased utilization of laparoscopy in general surgery and specialty specific practice as well as the increased prevalence of laparoscopy in general surgery training [29, 30]. Further studies will need to be conducted on more recent data to confirm if this trend continues.

Previous studies have shown that longer operative times are associated with a higher incidence of SSI, and there is a linear relation for operative time and risk of SSI [31]. Even though our LUHR group had statistically significant longer operative times (70 min vs. 44 min; p < 0.001), the LUHR group still had a lower incidence of composite SSI (1.1% vs. 1.9%; p < 0.01) as well as superficial SSI (0.9% vs. 1.5%; p = 0.026). This indicates that a longer operative time for LUHR compared to OUHR does not outweigh the increased risk of post-operative SSI. However, when broken down by obesity class, operative times increased as BMI increased in both LUHR (57 vs. 60 vs. 67 min; p < 0.001) and OUHR (34 vs. 37 vs. 44 min; p < 0.001) groups, suggesting that higher levels of obesity may lead to increased morbidity in the post-operative period.

Non-elective repair was found to be associated with a higher rate of superficial and composite SSI compared to elective surgery overall (considering both LUHR and OUHR) and for the OUHR group individually. This is consistent with prior studies; Neumayer et al. found that emergency surgery is an independent risk factor for SSI based on a NSQIP review [32]. However, when broken down to comparing only LUHR in the elective versus non-elective setting in our study, there was no significant difference in composite and superficial SSI rates. This supports the use of LUHR over OUHR in the non-elective setting.

Limitations of our study include a selection bias in regards to the operative approach utilized as our data is a retrospective review of the prospectively collected data. The mean BMI of the LUHR group was 37.5 versus 36.1 in the OUHR group (p < 0.001) which could be a representation of selection bias. Other limitations include the lack of certain data points in the NSQIP database. In regards to operation specifics, we were unable to compare hernia size, defect dimensions, use of mesh, and different minimally invasive techniques as there is no differentiation between laparoscopic and robotic repairs in the database. The literature has shown that not only BMI but also increased intra-abdominal pressure, abdominal circumference, central obesity and visceral obesity are associated with increased hernia formation as well as increased morbidity with surgical procedures [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. Long-term outcomes were unable to be assessed as our data was for 30-day outcomes only; potential long-term complications such as adhesion formation requiring subsequent hospitalization plus or minus operation, hernia recurrence, chronic pain, mesh complications including late or chronic infections, and fistula formation were unable to be evaluated. Further studies are necessary in order to decisively determine the optimal surgical approach to umbilical hernia repair in patients with obesity. Specific attention to the comparison of open, laparoscopic, and robotic umbilical hernia repairs in terms of short-term and long-term outcomes, while assessing more specific operative and patient characteristics would be valuable.

Even though the patients in the LUHR group had a higher BMI, higher rates of diabetes, hypertension, current smoking status, and longer operative times, they had decreased post-operative wound complications compared to patients in the OUHR group. This study supports the superiority of LUHR compared to OUHR in patients with obesity in regards to decreased wound complications, especially in the non-elective setting.

References

Muschaweck U (2003) Umbilical and epigastric hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am 83:1207–1221

Hales CM, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Freedman DS, Ogden CL (2018) Trends in obesity and severe obesity prevalence in US youth and adults by sex and age, 2007-2008 to 2015-2016. JAMA 319:1723–1725

Menzo EL, Hinojosa M, Carbonell A, Krpata D, Carter J, Rogers AM (2018) American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and American Hernia Society consensus guideline on bariatric surgery and hernia surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 14:1221–1232

Goodenough CJ, Ko TC, Kao LS, Nguyen MT, Holihan JL, Alawadi Z, Nguyen DH, Flores JR, Arita NT, Roth JS, Liang MK (2015) Development and validation of a risk stratification score for ventral incisional hernia after abdominal surgery; hernia expectation rates in intra-abdominal surgery (the HERNIA Project). J Am Coll Surg 220:405–413

Buckley FP 3rd, Vassaur HE, Jupiter DC, Crosby JH, Wheeless CJ, Vassaur JL (2016) Influencing factors for port-site hernias after single-incision laparoscopy. Hernia 20:729–733

Lau B, Kim H, Haigh PI, Tejirian T (2012) Obesity increased the odds of acquiring and incarcerating noninguinal abdominal wall hernias. Am Surg 78:1118–1121

Veljkovic R, Protic M, Gluhovic A, Potic Z, Milosevic Z, Stojadinovic A (2010) Prospective clinical trial of factors predicting the early development of incisional hernia after midline laparotomy. J Am Coll Surg 210:210–219

Sauerland S, Korenkov M, Kleinen T, Arndt M, Paul A (2004) Obesity is a risk factor for recurrence after incisional hernia repair. Hernia 8:42–46

Sugerman H, Windsor A, Bessos M, Wolfe L (1997) Intra-abdominal pressure, sagittal abdominal diameter and obesity comorbidity. J Intern Med 24:71–79

Lambert DM, Marceau S, Forse RA (2005) Intra-abdominal pressure in the morbidly obese. Obes Surg 15:1225–1232

Varela JE, Hinojosa M, Nguyen N (2009) Correlations between intra-abdominal pressure and obesity-related co-morbidities. Surg Obes Relat Dis 5:524–528

Noblett KL, Jensen JK, Ostergard DR (1997) The relationship of body mass index to intra-abdominal pressure as measured by a multichannel cystometery. Int Urogynecol J Plevic Floor Dysfunct 8:323–326

De Raet J, Delvaux G, Haentjens P, Van Nieuwenhove Y (2008) Waist circumference is an independent risk factor for the development of parastomal hernia after permanent colostomy. Dis Colon Rectum 51:1806–1809

Aquina CT, Rickles AS, Probst CP, Kelly KN, Deeb AP, Monson JR, Fleming FJ; Muscle and Adiposity Research Consortium (MARC) (2015) Visceral obesity, not elevated BMI, is strongly associated with incisional hernia after colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 58:220–227

Murray BW, Cipher DJ, Pham T, Anthony T (2011) The impact of surgical site infection on the development of incisional hernia and small bowel obstruction in colorectal surgery. Am J Surg 202:558–560

Martin ET, Kaye KS, Knott C, Nguyen H, Santarossa M, Evans R, Bertran E, Jaber L (2015) Diabetes and risk of surgical site infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 37:88–99

Zajak J, Králiková E, Pafko P, Bortlíček Z (2013) Smoking and postoperative complications. Rozhl Chir 92:501–505

McGreevy JM, Goodney PP, Birkmeyer CM, Finlayson SR, Laycock WS, Birkmeyer JD (2003) A prospective study comparing the complication rates between laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repairs. Surg Endosc 17:1778–1780

Pierce RA, Spitler JA, Frisella MM, Matthews BD, Brunt LM (2007) Pooled data analysis of laparoscopic vs. open ventral hernia repair: 14 years of patient data accrual. Surg Endosc 21:378–386

Cassie S, Okrainec A, Saleh F, Quereshy F, Jackson T (2014) Laparoscopic versus open elective repair of primary umbilical hernias: short-term outcomes from the American College of Surgeons National Surgery Quality Improvement Program. Surg Endosc 28:741–746

Wright BE, Beckerman J, Cohen M, Cumming JK, Rodriguez JL (2002) Is laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair with mesh a reasonable alternative to conventional repair? Am J Surg 184:505–508

Sauerland S, Walgenbach M, Habermalz B, Seiler CM, Miserez M (2011) Laparoscopic versus open surgical technicques for ventral or incisional hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD007781

Colon MJ, Kitamura R, Telem DA, Nguyen S, Divino CM (2013) Laparoscopic umbilical hernia repair is the preferred approach in obese patients. Am J Surg 205:231–236

Forbes SS, Eskicioglu C, McLeod RS, Okrainec A (2009) Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing open and laparoscopic ventral and incisional hernia repair with mesh. Br J Surg 96:851–858

Gonzalez R, Mason E, Duncan T, Wilson R, Ramshaw BJ (2003) Laparoscopic versus open umbilical hernia repair. J Soc Laparoendoscop Surg 7:323–328

Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Sreh A, Khan A, Subar D, Jones L (2017) Laparoscopic versus open umbilical or paraumbilical hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hernia 21:905–916

Regner JL, Mrdutt MM, Munoz-Maldonado Y (2015) Tailoring surgical approach for elective ventral hernia repair based on obesity and National Surgical Quality Improvement Program outcomes. Am J Surg 210:1024–1029

Mason RJ, Moazzez A, Sohn HJ, Berne TV, Katkhouda N (2011) Laparoscopic versus open anterior abdominal wall hernia repair: 30-day morbidity and mortality using the ACS-NSQIP database. Ann Surg 254:641–652

Davis CH, Shirkey BA, Moore LW, Gaglani T, Du XL, Bailey HR, Cusick MV (2018) Trends in laparoscopic colorectal surgery over time from 2005-2014 using the NSQIP database. J Surg Res 223:16–21

Mandrioli M, Inaba K, Piccinini A, Biscardi A, Sartelli M, Agresta F, Catena F, Cirocchi R, Jovine E, Tugnoli G, Di Saverio S (2016) Advances in laparoscopy for acute care surgery and trauma. World J Gastroentero 22:668–680

Cheng H, Chen BP, Soleas IM, Ferko NC, Cameron CG, Hinoul P (2017) Prolonged operative duration increases risk of surgical site infections: a systematic review. Surg Infect 18:722–735

Neumayer L, Hosokawa P, Itani K, El-Tamer M, Henderson WG, Khuri SF (2007) Multivariable predictors of postoperative surgical site infection after general and vascular surgery: results from the patient safety in surgery study. J Am Coll Surg 204:1178–1187

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Kristen N. Williams, Lala Hussain, Angela N. Fellner, and Katherine M. Meister have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, K.N., Hussain, L., Fellner, A.N. et al. Updated outcomes of laparoscopic versus open umbilical hernia repair in patients with obesity based on a National Surgical Quality Improvement Program review. Surg Endosc 34, 3584–3589 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-07129-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-019-07129-7