Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate the benefits of cholecystectomy on mitigating recurrent biliary complications following endoscopic treatment of common bile duct stone.

Methods

We used the data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database to conduct a population-based cohort study. Among 925 patients who received endoscopic treatment for choledocholithiasis at the first admission from 2005 to 2012, 422 received subsequent cholecystectomy and 503 had gallbladder (GB) left in situ. After propensity score matching with 1:1 ratio, the cumulative incidence of recurrent biliary complication and overall survival was analyzed with Cox’s proportional hazards model. The primary endpoint of this study is recurrent biliary complications, which require intervention.

Results

After matching, 378 pairs of patients were identified with a median follow-up time of 53 (1–108) months. The recurrent rate of biliary complications was 8.20% in the cholecystectomy group and 24.87% in the GB in situ group (p < 0.001). In the multivariate Cox regression analysis, the only independent risk factor for recurrent biliary complications was GB left in situ (hazard ratio [HR] 3.55, 95% CI 2.36–5.33).

Conclusions

Cholecystectomy after endoscopic treatment of common bile duct stone reduced the prevalence of recurrent biliary complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Gallstone is a common disease all over the world, though its prevalence and etiology differ among countries. Compared with a higher incidence of around 15% in the American population, for example, the incidence of the disease is slightly lower in Taiwan, ranging from 5.0 to 13.2% in different population subgroups [1,2,3]. In this population, common bile duct (CBD) stone accounted for 10–15%. However, some had primary bile duct stone not associated with GB stone, which occurs especially in Asian populations [4].

First developed in 1974, endoscopic treatment has become the treatment of choice for CBD stone [5, 6] and gallstone-related cholangitis [7]. The performance of cholecystectomy was advocated for following endoscopic treatment for common bile duct stone in a previous meta-analysis, which included several heterogeneous randomized trials [8]. Most western guideline recommended cholecystectomy after endoscopic clearance of CBD [9,10,11]. However, some studies have recently shown controversial results regarding its use in Asian populations, especially for the treatment of recurrent CBD stone and cholangitis [12,13,14,15,16]. Although cholecystectomy was recommended for this population, some patients still take the wait-and-see policy in clinical settings in Taiwan [17]. However, recurrent biliary complications may lead to possible severe complications, requiring the use of invasive treatments such as surgical, endoscopic, or percutaneous biliary procedures, and may cause excessive medical costs [18]. No previous population-based study for this topic has ever been conducted, to our knowledge. Thus, in this study, we designed a cohort study in Taiwan to understand the effects of cholecystectomy on recurrent biliary complications after endoscopic treatment for CBD stone using information from a research database.

Methods

Data source

The National Health Insurance program in Taiwan was launched on March 1, 1995. This program is compulsory and covers more than 99% of Taiwan’s population. Taiwan’s National Health Insurance research database (NHIRD) contains registration files and original claims data for reimbursement purposes from the program [19]. The dataset was released for scientific research purposes after de-identification and anonymization to protect subject privacy. Most interestingly, the dataset received had complete records of NHI procedure codes. The NHI procedure codes are the foundations of the institute claims for government reimbursement. There is an independent peer review evaluation system for the indication of the procedure based on the medical records from the hospital. If there are no enough reasons for the procedure, the institute will not be paid, and may even incur a severe penalty from the Bureau of National Health Insurance (BNHI). This study was approved by the Ethics Institution Review Board of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

The Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 (LHID 2005) is a subset of the NHIRD that contains data of 1,000,000 beneficiaries enrolled in year 2005. The Registry for Beneficiaries (ID) of the NHIRD contains data from the year 1996 to 2013 (http://www.nhi.gov.tw/english/index.aspx).

Study population

This was an observational retrospective cohort study. Its main goal was to identify patients with first episodes of common bile duct stone who were treated with endoscopic treatment and who never received cholecystectomy. We identified all patients who were admitted with the diagnosis of cholelithiasis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9CM] codes 574) and who underwent an endoscopic biliary procedure during the same admission between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2013. We identified inpatient order records with specific NHI procedure codes to pinpoint the endoscopic biliary procedures, which included endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD), endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD), endoscopic sphincterotomy, endoscopic balloon sphincteroplasty, and endoscopic papillotomy with or without stone removal (Supplementary Table S1). The first day of the index admission is defined as the index date. Patients with previously diagnosed malignant disease (ICD-9-CM codes 140-208) were excluded. Furthermore, to reduce the influence of other underlying biliary conditions, patients who had records of any benign biliary disease (ICD-9-CM codes 574,575,576) or who received any type of cholecystectomy were excluded from this study (Supplementary Table S2). Patients who were younger than 18 years of age were also excluded, as were those with a follow-up period of less than 1 year after the index day.

Outcome and comorbidities

The primary endpoint of this study was recurrent biliary complications that required intervention. The recurrent date was defined as the first day the patient admitted with the diagnosis of cholelithiasis (ICD code 574) and received an endoscopic, percutaneous, or surgical intervention, other than cholecystectomy. The relevant procedures were detected based on NHI procedure code. Cholecystitis is excluded from the outcome measurement because there would be bias in the cholecystectomy group if it was included. After index day, any patients who received any type of cholecystectomy before recurrence of biliary complications were assigned to the cholecystectomy group. Otherwise, patients were assigned to the GB in situ group. Both groups were followed up until the date of recurrent biliary complication, death, or the end of 2013.

Death was defined as any patients who demonstrated documented death in inpatient expenditures, by admission and emergency visit with major disease, or those who dropped out from the NHI program within 28 days. Comorbidities and known risk factors of cholelithiasis were defined as more than one outpatient record or any inpatient records that included hypertension (ICD-9-CM codes 401–405), diabetes mellitus(DM) (ICD-9 code 250), hyperlipidemia (ICD-9-CM codes 272), hepatitis B (ICD-9-CM codes V02.61,070.20, 070.22, 070.30, and 070.32), hepatitis C (ICD-9-CM codes V02.62,070.41, 070.44, 070.51, and 070.54), menopause status (ICD-9-CM codes V49.81,627.2, 627.8, and 627.9), chronic liver disease (ICD-9-CM codes 571) or chronic kidney disease necessitating chronic dialysis (confirmed by Registry for Catastrophic Illness Patient Database, a subpart of the NHIRD).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R (v3.3.1). The association between cholecystectomy and demographic factors, comorbidities, and risk factors were analyzed by Chi-square test for categorical variables and by Student’s t test for continuous variables. To eliminate the channeling bias for cholecystectomy, we used propensity score matching with nearest neighbor and a 1:1 ratio between the two groups with R package “MatchIt” [20]. The parameters used for matching include age, gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, menopause status, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease necessitating chronic dialysis use, and year of index admission. The cumulative incidence of recurrent biliary complication was analyzed with the Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test for differences between the two groups, and plotted using R package “survminer.” Univariate and multivariate analyses were analyzed with a Cox proportional hazard model to estimate the hazard ration (HR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for recurrent biliary complication. The time to date of cholecystectomy was treated as a time-dependent covariate from index date in the Cox model. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

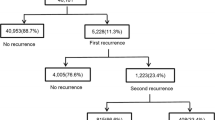

Between January 2005 and December 2013, we identified a total of 2629 patients who were admitted to hospitals with the diagnosis of cholelithiasis and who received endoscopic biliary procedures. A total of 1592 patients were excluded, including 441 patients who had malignant disease, 1150 patients who had benign biliary disease and/or cholecystectomy before the index date, and one patient was younger than 18 years old. An additional 112 patients were excluded because of having less than 1 year of follow-up (Fig. 1).

A total of 925 patients who had a first episode of cholelithiasis treated with an endoscopic biliary procedure were enrolled in the study cohort. Among them, 53.5% were male with a mean age of 62.31 years old [standard deviation (SD): 17.58]. The median follow-up time was 53 months (interquartile range, 47.9). There were 422 patients in the cholecystectomy group and 503 patients in the GB in situ group. Following propensity score matching, there were 378 patients allocated in each arm. Table 1 showed the distribution of demographic and comorbidities before and after matching. Before matching, older age, more DM, and hepatitis B were associated with GB in situ group patients. After matching, there were no significant differences in any of the considered factors between the two groups.

During the follow-up period, 125 patients had recurrent biliary complications for an overall recurrence rate of 19.8%. Figure 2 shows the cumulative incidence curve between the cholecystectomy and GB in situ groups. Patients who underwent cholecystectomy showed a significant lower cumulative incidence of biliary recurrence when compared with individuals in the GB in situ (p < 0.001). In both groups, we observed a peak of recurrent biliary complications occurring within the first year, with the recurrence rates for the cholecystectomy group and GB in situ group being 4.8 and 18.4%, respectively. The risk of recurrent biliary complications in those patients older than 65 years (hazard ration (HR): 1.53; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.07–2.18, p = 0.018) and in the GB in situ group (HR: 2.62; 95% CI 1.74–3.94, p < 0.001) were significantly higher (Table 2). In multivariate analysis, only GB left in situ was the independent risk factor for recurrent biliary complication (HR: 3.55; 95% CI 2.36–5.33, p < 0.001) (Table 3). Although cholecystectomy showed an overall survival benefit (log-rank test, p = 0.023) (Fig. 3), this was not demonstrated in the Cox regression model (HR: 1.29; 95% CI 0.82–2.04, p = 0.27).

Discussion

Controversy still exists regarding whether cholecystectomy should be performed after endoscopic treatment for CBD stone for recurrent biliary complications. Previous studies have shown recurrent rates of biliary complications of 4.1–14.7% in cholecystectomy groups and 8.2–25.6% in GB in situ groups [16, 17, 21,22,23,24]. However, all of the studies that considered this issue were restricted to a single institution with a limited number of patients [16, 17, 22, 24]. This current study is based on the Taiwan NHIRD and thus, the patients are randomly selected from medical institutes all over the country, which lowers the physician-related bias. An additional advantage of use of the NHIRD is integrity of follow-up, because of high coverage in Taiwan. As long as the patient receives medical care in an institute covered by the NHI in Taiwan, the data will be collected. We also excluded patients who had history of benign biliary disease; in other words, these patients were all fresh cases of common bile duct stone. By doing this, we were able to identify the patients with records of cholecystectomy or recurrent biliary complications more clearly.

Several important and interesting issues are discovered in this study.

First, our study found that patients older than 65 years of age demonstrated an increased risk for recurrent biliary complications following endoscopic treatment for CBD stone; but this was not defined as an independent associated factor.

Second, cholecystectomy following endoscopic biliary procedure for CBD stone will markedly decrease the incidence rate of recurrent biliary complications from 24.8 to 8.2%. On the contrary, if the patient decided to leave GB in situ, they would have a higher recurrent biliary complication rate of up to 24.8%. However, overall survival is not affected by GB status after the index episode.

Third, although the risk of biliary complications in the cholecystectomy group is significantly decreased, they still can happen. Importantly, our study demonstrated the peak of recurrence is within several months, and seldom occurs after 2 years, with an overall 8.2% recurrence rate. Type 1 or 2 periampullary diverticulum and multiple CBD stones may explain the causes of recurrent biliary complications after combined endoscopic treatment and cholecystectomy [21]. The other possible explanation is that the residual CBD stones after cholecystectomy or in situ stimulate the formation of new stones in the biliary system.

Fourth, the surgical mortality rate for cholecystectomy was as low as 0.22–0.4% [25, 26], with major morbidities being around 5% [27]. In our study, the risk of recurrent biliary complication in those who were older than 65 years of age increased, and the severity of cholangitis is known to increase with age. The mortality of cholangitis in a recent series ranges from 0.5–24.1% [28]. Therefore, to prevent further recurrence in elderly patients, early cholecystectomy after endoscopic treatment for CBD stones may be justified as an effective approach.

Although we suggest that cholecystectomy could decrease the risk of biliary complications, there were still some limitations in this study. First, this study was unable to obtain patient medical records prior to 1995 because the NHI system had been initiated. Second, if any patients had received cholecystectomy more than 10 years ago, and had no related medical problems recorded in the NHIRD until 2005, such would be a source of bias. Third, several studies reported that it is not necessary to perform cholecystectomy in patients without evidence of GB stone to prevent biliary complications [13, 16, 22]. Because of the lack of detailed image reports, we couldn’t identify if the patients in the GB in situ group still had gallstone. Finally, this study included only patients randomly selected from the Taiwanese population; thus, further study of population data from Western countries is still needed to provide a more comprehensive picture. Furthermore, a multicenter randomized control trial may still be needed to evaluate the benefit of cholecystectomy for patients with no residual gallstone after endoscopic removal of common bile duct stone.

In conclusion, our study shows that cholecystectomy significantly reduced the incidence of recurrent biliary complications—from 24.8 to 8.2%—in patients who received endoscopic treatment for common bile duct stone. Cholecystectomy should be recommended for these patients with acceptable surgical and anesthesia risk.

References

Shen HC, Hu YC, Chen YF, Tung TH (2014) Prevalence and associated metabolic factors of gallstone disease in the elderly agricultural and fishing population of taiwan. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2014:876918

Chen CH, Huang MH, Yang JC, Nien CK, Etheredge GD, Yang CC, Yeh YH, Wu HS, Chou DA, Yueh SK (2006) Prevalence and risk factors of gallstone disease in an adult population of Taiwan: an epidemiological survey. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 21:1737–1743

Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR (1999) Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology 117:632–639

Tazuma S (2006) Gallstone disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and classification of biliary stones (common bile duct and intrahepatic). Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 20:1075–1083

Classen M, Demling L (1974) Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the papilla of vater and extraction of stones from the choledochal duct (author’s transl). Dtsch Med Wochenschr 99:496–497

Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y (1974) Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc 20:148–151

Boender J, Nix GA, de Ridder MA, Dees J, Schutte HE, van Buuren HR, van Blankenstein M (1995) Endoscopic sphincterotomy and biliary drainage in patients with cholangitis due to common bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol 90:233–238

McAlister VC, Davenport E, Renouf E (2007) Cholecystectomy deferral in patients with endoscopic sphincterotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev :CD006233

Agresta F, Campanile FC, Vettoretto N, Silecchia G, Bergamini C, Maida P, Lombari P, Narilli P, Marchi D, Carrara A, Esposito MG, Fiume S, Miranda G, Barlera S, Davoli M, Italian Surgical Societies Working G (2015) Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: consensus conference-based guidelines. Langenbecks Arch Surg 400:429–453

Internal Clinical Guidelines T (2014) National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. Gallstone Disease: Diagnosis and Management of Cholelithiasis, Cholecystitis and Choledocholithiasis. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London

Committee ASoP, Maple JT, Ikenberry SO, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Decker GA, Early D, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher D, Fisher L, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Jain R, Jue T, Khan K, Krinsky ML, Malpas P, Ben-Menachem T, Sharaf RN, Dominitz JA (2011) The role of endoscopy in the management of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc 74:731–744

Heo J, Jung MK, Cho CM (2015) Should prophylactic cholecystectomy be performed in patients with concomitant gallstones after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones? Surg Endosc 29:1574–1579

Lai KH, Lin LF, Lo GH, Cheng JS, Huang RL, Lin CK, Huang JS, Hsu PI, Peng NJ, Ger LP (1999) Does cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy prevent the recurrence of biliary complications? Gastrointest Endosc 49:483–487

Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, Janssen IM, Bolwerk CJ, Timmer R, Boerma EJ, Obertop H, Huibregtse K, Gouma DJ (2002) Wait-and-see policy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile-duct stones: a randomised trial. Lancet 360:761–765

Lau JY, Leow CK, Fung TM, Suen BY, Yu LM, Lai PB, Lam YH, Ng EK, Lau WY, Chung SS, Sung JJ (2006) Cholecystectomy or gallbladder in situ after endoscopic sphincterotomy and bile duct stone removal in Chinese patients. Gastroenterology 130:96–103

Kim MH, Yeo SJ, Jung MK, Cho CM (2016) The impact of gallbladder status on biliary complications after the endoscopic removal of choledocholithiasis. Dig Dis Sci 61:1165–1171

Lai JH, Wang HY, Chang WH, Chu CH, Shih SC, Lin SC (2012) Recurrent cholangitis after endoscopic lithotripsy of common bile duct stones with gallstones in situ: predictive factors with and without subsequent cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 22:324–329

Williams EJ, Green J, Beckingham I, Parks R, Martin D, Lombard M, British Society of G (2008) Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut 57:1004–1021

(2014) National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan, R.O.C. National Health Insurance Annual Report

King G, Ho D, Stuart EA, Imai K (2011) MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference

Oak JH, Paik CN, Chung WC, Lee KM, Yang JM (2012) Risk factors for recurrence of symptomatic common bile duct stones after cholecystectomy. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012:417821

Cui ML, Cho JH, Kim TN (2013) Long-term follow-up study of gallbladder in situ after endoscopic common duct stone removal in Korean patients. Surg Endosc 27:1711–1716

Sugiyama M, Atomi Y (2002) Risk factors predictive of late complications after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones: long-term (more than 10 years) follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol 97:2763–2767

Nakai Y, Isayama H, Tsujino T, Hamada T, Kogure H, Takahara N, Mohri D, Matsubara S, Yamamoto N, Tada M, Koike K (2016) Cholecystectomy after endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stones reduced late biliary complications: a propensity score-based cohort analysis. Surg Endosc 30:3014–3020

Steiner CA, Bass EB, Talamini MA, Pitt HA, Steinberg EP (1994) Surgical rates and operative mortality for open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Maryland. N Engl J Med 330:403–408

Csikesz N, Ricciardi R, Tseng JF, Shah SA (2008) Current status of surgical management of acute cholecystitis in the United States. World J Surg 32:2230–2236

Giger UF, Michel JM, Opitz I, Th Inderbitzin D, Kocher T, Krahenbuhl L, Swiss Association of L, Thoracoscopic Surgery Study G (2006) Risk factors for perioperative complications in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: analysis of 22,953 consecutive cases from the Swiss Association of Laparoscopic and Thoracoscopic Surgery database. J Am Coll Surg 203:723–728

Kimura Y, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Gouma DJ, Garden OJ, Buchler MW, Windsor JA, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Miura F, Higuchi R, Gabata T, Hata J, Gomi H, Dervenis C, Lau WY, Belli G, Kim MH, Hilvano SC, Yamashita Y (2013) TG13 current terminology, etiology, and epidemiology of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20:8–23

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Chi-Tung Cheng, Chun-Nan Yeh, Kun-Chun Chiang, Ta-Sen Yeh, Kuan-Fu Chen, Shao-Wei Chen have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, CT., Yeh, CN., Chiang, KC. et al. Effects of cholecystectomy on recurrent biliary complications after endoscopic treatment of common bile duct stone: a population-based cohort study. Surg Endosc 32, 1793–1801 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5863-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5863-8