Abstract

Background

Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy has been introduced as an alternative to standard laparoscopy. However, to date, it has not been established whether intraabdominal placement of a hand abrogates the benefits of minimally invasive techniques. The authors hypothesized that the hand-assisted approach confers advantages of minimal access surgery over traditional open colectomy.

Methods

Consecutive patients undergoing elective open (OC) and hand-assisted (HALC) colon resections were retrospectively reviewed. Open colectomies performed by the laparoscopic surgeons were excluded. Outcome measures included patient demographics, operative time, perioperative complications, operative and total hospital charges, and length of hospital stay. Statistical analysis was performed with a p value less than 0.05 considered significant.

Results

The study identified and reviewed 323 consecutive elective OCs and 66 consecutive elective HALCs. Of these, 228 OCs (70.6%) and 52 HALCs (78.8%) were left-sided. The two groups were similar in age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). The mean operative time was longer in the HALC group (202 vs 160 min; p < 0.05). No major intraoperative complications occurred in either group, and no conversions from HALC to OC were performed. Postoperatively, 14 OC patients (3.8%) required blood transfusion versus no HALC patients. The rate of wound infections also was higher in the OC group (3.4%, n = 11) than in the HALC group (1.5%, n = 1) (p = 0.04). All seven mortalities (2.3%) occurred in the OC group. The median hospital stay was significantly shorter in the HALC group (5.3 vs 8.4 days; p < 0.001). The total hospital charges were significantly lower in the HALC group ($24,132 vs $33,150; p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy is a safe alternative to traditional open colonic resection. In this series, it was associated with decreased postoperative morbidity and mortality. Despite longer operative times, the use of the hand-assisted techniques significantly reduced the hospital stay and decreased the total hospital charges. Overall, in the elective setting, hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy appears to be advantageous over the traditional open colectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent years, laparoscopic colectomy (LC) has become popular among colorectal and general surgeons alike for the advantages it provides compared with standard open colectomy (OC). Although traditional open laparotomies allow the greatest capacity for tactile feedback and direct visualization, the large laparotomy incision has well-known postoperative disadvantages including prolonged ileus, dehydration, increased pain, prolonged convalescence, and frequent wound complications [1–5]. On the other hand, the benefits of laparoscopy include decreased postoperative pain and wound complications, quicker return of bowel function, shorter hospital stay, and reduced total costs [6–9]. However, the steep learning curve and decreased tactile feedback of purely laparoscopic approaches have limited their widespread use to date. With hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (HALS), the surgeon’s hand is inserted through an access device that conforms to a 6- to 8-cm incision in the abdominal wall. This provides tactile feedback and facilitates difficult dissections.

Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy (HALC) has been introduced as an alternative surgical technique, essentially bridging both open and laparoscopic approaches [10–12]. Whether intraabdominal placement of a hand during HALC abrogates the benefits of minimally invasive techniques remains to be established. We hypothesized that the hand-assisted approach confers the advantages of minimal access surgery over the traditional open approach to colectomy. In this study, we evaluated perioperative outcomes of HALC and open approaches for patients undergoing elective colon resections.

Materials and methods

After obtaining institutional review board approval, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of adult patients undergoing a colonic resection at a tertiary care hospital institution over an 8-year period (January 2000 to December 2008). The patients were divided in two groups: OC and HALC. Open colectomies performed by laparoscopic surgeons were excluded. Records were identified using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) codes for colonic resection. The main outcome variable included demographics, preoperative comorbidities, operative details, perioperative complications, postoperative 30-day mortality, length of hospital stay, and operative and total hospital charges.

Medical comorbidities were defined as hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, and end-stage renal disease. Postoperative wound infection was defined as erythema of the skin incision or wound drainage requiring antibiotics, local wound care, or both. Wound dehiscence was defined as disruption of the fascial closure resulting in exposed viscera and requiring surgical intervention.

A computed tomography (CT) scan with oral or rectal contrast was used to diagnose or exclude anastomotic leak. Clinically significant ileus was defined as that requiring nasogastric tube decompression beyond postoperative day 5. Pulmonary complications included roentgen-proven pneumonias and respiratory failures defined by the need for mechanical ventilation beyond the immediate postoperative period. Cardiac complications were included in the setting of significant cardiac enzyme elevations and electrocardiogram findings found consistent with cardiac events. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise specified.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Wilcoxon rank sum and Student’s t-test were used for continuous variables. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

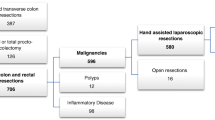

Between January 2000 and December 2008, 389 consecutive eligible adult patients undergoing elective colonic resections were identified and reviewed. Of these resections, 323 were performed via a laparotomy and 66 using the hand-assisted approach. Left-sided resections were more common in both groups (71% in the OC group; 79% in the HALC group). No statistical differences in gender, age, or body mass index (BMI) were noted between the two groups. The indications for colectomy included diverticular disease, colon cancer, colon polyp not resectable by endoscopic technique, and inflammatory bowel disease. No statistical differences between these groups were observed (Table 1).

For colon cancer resections, all procedures were adequate from an oncologic standpoint (e.g., negative resection margins, adequate lymph node sampling). Of the 389 patients, 191 (49%) had at least one significant comorbid condition. However, the two groups did not differ with regard to comorbidities (Table 2).

The mean operative time was significantly longer in the HALC group (202 vs 160 min; p < 0.05). The estimated blood loss was comparable between the two groups (85 vs 70 ml; p = 0.12). No major intraoperative complications occurred in either group, and the HALC group had no conversions to OC.

The incidence of postoperative complications is summarized in Table 3. Postoperatively, 14 (3.8%) patients in the OC group required blood transfusion compared with none in the HALC group. Prolonged ileus occurred for 21 (6.4%) of the OC patients and 3 (3%) of the HA patients (p < 0.05). The OC group had significantly more wound complications than the HALC group including wound infection (11 [3.4%] vs 1 [1.5%]; p = 0.04) and fascial dehiscence (9 [2.8%] vs none; p < 0.05). Cardiopulmonary events also were more common in the OC group (n = 32, 10%) than in the HALC group (n = 3, 4.5%) (p < 0.05). All seven mortalities (2.2%) that occurred were in the OC group and attributed to cardiopulmonary events. The median hospital stay was significantly longer in the OC group (8.4 days; range, 4–66 days) than in the HALC group (5.3 days; range, 2–21 days) (p < 0.0001). Finally, although the operating room charges were higher in the HALC group, the total hospital charges were significantly higher in the OC group (p < 0.001; Table 4).

Discussion

Hand-assisted LC has been an established alternative to LC for more than 10 years. The addition of tactile feedback to standard laparoscopy has the potential to enhance the surgeon’s manipulation of tissues, promote safe blunt dissection, and enable atraumatic retraction [12]. Although the benefits of hand-assisted colectomies have been compared with those of “pure” laparoscopic techniques by many investigators [13–16], the analysis comparing HALC and OC has been insufficient to date. Many opponents of HALC have suggested that the need for a hand-port incision eliminates the benefit of minimal access. Our results, however, suggest that hand-assisted LC is a safe alternative to traditional OC and that it is associated with decreased perioperative morbidity and charges as well as improved overall outcomes.

Findings have shown that minimally invasive approaches to colon resections are associated with longer operative times [9, 16]. This likely is due to the additional time spent obtaining pneumoperitoneum, abdominal access, and placement of the hand port. Moreover, technically challenging steps such as laparoscopic colonic mobilization, intracorporeal intestinal resection, and anastomosis creation all are likely factors prolonging the surgery time compared with OC. The operative time for this series was significantly longer for the HALC group than for the OC group. This is consistent with the literature, in which the median operative times differ 13 to 81 min [16–19]. Although longer operative times did not seem to result in any clinically significant adverse effects, the open approach may be preferred when shorter anesthesia time is of the highest priority.

We also found that overall postoperative complication rates were significantly higher in the OC group than in the HALC group. For our study, we included cardiopulmonary events, anastomotic leaks, and wound infections requiring antibiotic therapy to determine our morbidity rate. These findings are consistent with a review series by Aalbers et al. [20] with reported postoperative morbidity rates ranging from 5% to 20% for HALC patients and 17% to 30% for OC patients. With the exception to the study of Anderson et al. [16], no previous study comparing HALC and OC has found a significant difference in mortality. Interestingly, the patients in our OC group had a significant increase in the number of cardiopulmonary events versus the HALC group (Table 3). Additionally, all seven deaths in the OC group were attributed to cardiopulmonary events. Although this finding was not observed be statistically significant, it further underscores the safety of HALC compared with the open technique.

In addition to higher systemic complications seen in OC cases, the typically larger incision carries a greater risk of infection, hernia, and dehiscence [8, 16]. The incision for HALC generally is much shorter than for OC, averaging only 6 to 8 cm to accommodate the surgeon’s hand and allow for specimen removal. Although the exact sizes of incisions were not documented in our series, in our experience, typical open incisions approximately double those needed for HALC.

It is not well documented whether HALC is associated with wound complication rates resembling those for OC or whether the benefit of a smaller incision maintains the advantages associated with LC. Previous studies comparing HALC and OC have found higher wound infection rates for OC patients [16, 21]. Our findings showed significantly a higher wound complication rate in the OC group as well, including infection and fascial dehiscence.

Some studies have suggested that the hand port device itself may serve as a barrier to wound contamination, although more investigation is needed to support this theory [22, 23]. Overall, it appears that HALC is able to maintain the advantages of minimally invasive surgery over OC in terms of wound complication rates.

Considering the increase in postoperative complications experienced by the OC group, it is not surprising that the hospital stay was significantly longer than for the patients in the HALC group. These findings are consistent with a literature review reporting that the average hospital of stay for HALC patients is 2 to 4 days shorter than for OC patients [16, 19, 21].

In addition to a higher rate of wound complications, the open group required an increase in blood transfusions and experienced significantly more frequent instances of prolonged ileus than the HALC group. All these factors likely contributed to a longer hospital stay for the OC group in our series.

Surgical costs remain an important issue in current health care. In our study, we found higher total hospital charges in the OC group despite higher operative charges for HALC procedures (Table 4). The increased operative time together with costs of disposable surgical equipment (e.g., trocars, hand port, energy sources) likely translated to significantly higher operative charges for the HALC group (Table 4). However, the total hospital charges were significantly less for the HALC group ($33,150 for OC vs $24,132 for HALC; p < 0.001). This most likely reflects fewer complications and expeditious recovery experienced by patients in our hand-assisted group.

Interestingly, most of the current literature on cost analysis for HALC or LC versus OC reports no difference in overall costs. These findings usually are explained by the fact the higher laparoscopic procedural costs are offset by the longer convalescence of open surgery [9, 17, 24]. Our findings of a significant difference in total hospital charges may be explained by the fact that surgeons currently are more facile with the hand-assisted technique. Furthermore, many energy sources and stapling devices previously used only for the laparoscopic techniques currently are used routinely for open procedures, thus narrowing the difference between operative instrumentation costs for standard and minimally invasive procedures. Overall, it appears that fewer complications and shorter hospital stays have significantly reduced the total costs of hand-assisted resections compared with open colon resections.

Conclusion

Hand-assisted LC is a safe alternative to traditional open colonic resections. Although hand-assisted colectomy involves a small laparotomy incision for a hand-access device, it appears that HALC maintains the advantages of laparoscopic surgery over open surgery with respect to systemic morbidity, wound complications, and hospital stay. In addition, despite longer operative times, use of the hand-assisted techniques resulted in significantly decreased total hospital charges. In the elective setting, hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy appears to maintain the advantages of minimally invasive techniques.

References

Kelly JJ, Kercher KW, Gallagher KA, Litwin DE, Arous EJ (2002) Hand-assisted laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass versus open bypass for occlusive disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 12:339–343

Medeiros LR, Rosa DD, Bozzetti MC, Fachel JM, Furness S, Garry R, Rosa MI, Stein AT (2009) Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for benign ovarian tumour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD004751

Schietroma M, Carlei F, Franchi L, Mazzotta C, Sozio A, Lygidakis NJ, Amicucci G (2004) A comparison of serum interleukin-6 concentrations in patients treated by cholecystectomy via laparotomy or laparoscopy. Hepatogastroenterology 51:1595–1599

Alpay Z, Saed GM, Diamond MP (2008) Postoperative adhesions: from formation to prevention. Semin Reprod Med 26:313–321

Lamvu G, Zolnoun D, Boggess J, Steege JF (2004) Obesity: physiologic changes and challenges during laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:669–674

Young-Fadok TM, HallLong K, McConnell EJ, Gomez Rey G, Cabanela RL (2001) Advantages of laparoscopic resection for ileocolic Crohn’s disease: improved outcomes and reduced costs. Surg Endosc 15:450–454

Kennedy GD, Heise C, Rajamanickam V, Harms B, Foley EF (2009) Laparoscopy decreases postoperative complication rates after abdominal colectomy: results from the national surgical quality improvement program. Ann Surg 249:596–601

Senagore AJ, Stulberg JJ, Byrnes J, Delaney CP (2009) A national comparison of laparoscopic vs open colectomy using the National Surgical Quality Improvement Project data. Dis Colon Rectum 52:183–186

Shabbir A, Roslani AC, Wong KS, Tsang CB, Wong HB, Cheong WK (2009) Is laparoscopic colectomy as cost beneficial as open colectomy? ANZ J Surg 79:265–270

Kusminsky RE, Boland JP, Tiley EH, Deluca JA (1995) Hand-assisted laparoscopic splenectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc 5:463–467

Ballaux KE, Himpens JM, Leman G, Van den Bossche MR (1997) Hand-assisted laparoscopic splenectomy for hydatid cyst. Surg Endosc 11:942–943

Litwin DE, Novitsky Y, Kercher KW, Sandor A, Yood SM, Kelly JJ, Meyers WC, Gallagher KA (2000) Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery. Surg Technol Int IX:43–46

Study Group HALS (2000) Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery vs standard laparoscopic surgery for colorectal disease: a prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc 14:896–901

Targarona EM, Gracia E, Rodriguez M, Cerdan G, Balague C, Garriga J, Trias M (2003) Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery. Arch Surg 138:133–141 discussion 141

Nakajima K, Lee SW, Cocilovo C, Foglia C, Sonoda T, Milsom JW (2004) Laparoscopic total colectomy: hand-assisted vs standard technique. Surg Endosc 18:582–586

Anderson J, Luchtefeld M, Dujovny N, Hoedema R, Kim D, Butcher J (2007) A comparison of laparoscopic, hand-assist and open sigmoid resection in the treatment of diverticular disease. Am J Surg 193:400–403 (discussion 403)

Maartense S, Dunker MS, Slors JF, Cuesta MA, Gouma DJ, van Deventer SJ, van Bodegraven AA, Bemelman WA (2004) Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis: a randomized trial. Ann Surg 240:984–991 (discussion 991–982)

Zhang LY (2006) Hand-assisted laparoscopic vs open total colectomy in treating slow transit constipation. Tech Coloproctol 10:152–153

Chung CC, Ng DC, Tsang WW, Tang WL, Yau KK, Cheung HY, Wong JC, Li MK (2007) Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open right colectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 246:728–733

Aalbers AG, Doeksen A, VANBH MI, Bemelman WA (2009) Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open approach in colorectal surgery: a systematic review. Colorectal Dis 12:287–295

Kang JC, Chung MH, Chao PC, Yeh CC, Hsiao CW, Lee TY, Jao SW (2004) Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy vs open colectomy: a prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc 18:577–581

Kurian MS, Patterson E, Andrei VE, Edye MB (2001) Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery: an emerging technique. Surg Endosc 15:1277–1281

Meijer DW, Bannenberg JJ, Jakimowicz JJ (2000) Hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery: an overview. Surg Endosc 14:891–895

Noblett SE, Horgan AF (2007) A prospective case-matched comparison of clinical and financial outcomes of open versus laparoscopic colorectal resection. Surg Endosc 21:404–408

Disclosures

Sean B. Orenstein, Heidi L. Elliott, Louis A. Reines, and Yuri W. Novitsky have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orenstein, S.B., Elliott, H.L., Reines, L.A. et al. Advantages of the hand-assisted versus the open approach to elective colectomies. Surg Endosc 25, 1364–1368 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1368-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-010-1368-4