Abstract

Background

The traditional approach to palliating patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) has been open gastrojejunostomy (OGJ). More recently endoscopic stenting (ES) and laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy (LGJ) have been introduced as alternatives, and some studies have suggested improved outcomes with ES. The aim of this review is to compare ES with OGJ and LGJ in terms of clinical outcome.

Method

A systematic literature search and review was performed for the period January 1990 to May 2008. Original comparative studies were included where ES was compared with either LGJ or OGJ or both, for the palliation of malignant GOO.

Results

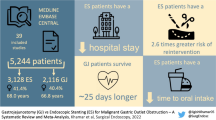

Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria (10 retrospective cohort studies, two randomised controlled trials and one prospective study). Compared with OGJ, ES resulted in an increased likelihood of tolerating an oral intake [odds ratio (OR) 2.6, p = 0.02], a shorter time to tolerating an oral intake (mean difference 6.9 days, p < 0.001) and a shorter post-procedural hospital stay (mean difference 11.8 days, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between 30-day mortality, complication rates or survival. There were an inadequate number of cases to quantitatively compare ES with LGJ.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates improved clinical outcomes with ES over OGJ for patients with malignant GOO. However, there is insufficient data to adequately compare ES with LGJ, which is the current standard for operative management. As these conclusions are based on observational studies only, future large well-designed randomised controlled trials (RCTs) would be required to ensure the estimates of the relative efficacy of these interventions are valid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is a recognised complication of malignancies of the upper gastrointestinal (UGI) tract. The most common causes are pancreatic and gastric malignancies, with lymphomas, ampullary carcinomas, biliary tract cancers and metastases also contributing. In patients with pancreatic cancer, it is estimated that 15–20% of patients develop gastric outlet obstruction [1]. Associated symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension and the sequelae of malnutrition, contribute substantially to morbidity in patients who are often terminally ill with limited quality and quantity of remaining life.

In the palliative setting, a major clinical goal for patients with malignant GOO is to restore the ability to tolerate an oral diet. Given that median survival in this patient group may be as short as 3–4 months [1, 2], an ideal procedure should restore oral intake quickly, with few complications, short hospital stay and without negative impact on survival.

The traditional approach for the palliation of malignant GOO has been open gastrojejunostomy (OGJ). More recently there have been reports of laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy (LGJ) [3, 4], and although its role has not been clearly defined, many now believe it to be safer than OGJ [5]. Over the past decade or so there has also been an increasing experience with the use of palliative endoscopic stenting (ES); a number of different types of upper GI stents have since become available [6] and the procedure is increasingly advocated and performed [7].

Two previous reviews have suggested significant clinical advantages for ES over OGJ [8, 9]. Since the publication of these reviews a number of additional studies have been published, further comparing the clinical and practical merits of ES and OGJ. The aim of this study is to provide an updated systematic review comparing ES with OGJ and LGJ with respect to ability to tolerate an oral intake, hospital stay, mortality at 30 days, length of survival, complication rate and associated costs.

Methods

Literature search

A comprehensive search for relevant clinical trials was undertaken for the period January 1990 to May 2008. Included sources were Medline, EMBASE, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, the Cochrane Library and online registers of controlled clinical trials. The search was not language restricted and combined the following terms: “gastric outlet, gastroduodenal or duodenal obstruction”, “gastrojejunostomy, gastroenterostomy or surgical bypass”, and “endoscop$ and stent”. Reference lists of published articles were hand-searched to ensure inclusion of all possible studies.

Study inclusion and assessment

Only clinical studies directly comparing endoscopic stenting and gastrojejunostomy for palliative management of gastric outlet or duodenal obstruction were included. These included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective cohort comparison studies. Studies were not excluded on the basis of sample size or language. Studies reported only in abstract form were excluded, and when more than one paper reported results from the same patient population, only the most recent study was included.

Data extraction

Studies were appraised and data were abstracted independently by two reviewers on a pre-defined proforma. The primary clinical outcomes examined were: number of patients tolerating an oral intake, time to oral intake, length of hospital stay (after intervention to hospital discharge), 30-day mortality, survival and complications. It was intended that a cost analysis also be undertaken with regard to total relative costs of each treatment method; however, inadequate data was found from the literature to report this outcome.

Complications were defined as either technical (e.g. stent failure and migration), surgical (e.g. stent obstruction, anastomotic leak, peritonitis, haemorrhage or bowel obstruction) or medical (e.g. respiratory tract infection, myocardial infarction, acute renal failure or sepsis). Major complications were defined as being life-threatening or severe, and usually requiring additional major interventions or hospitalisation. Minor complications were recognised as not significantly extending hospital stay, nor leading to further interventions or hospitalisation. Besides wound infections, which were defined as a minor complication, minor complications were not reported in the present study because of their wide variability and relative infrequency.

Information on LGJ and OGJ populations were collected separately for subgroup comparison. This was possible in all but one study by Jeurnink et al. in which the outcomes for both LGJ and OGJ were grouped together and could not be extracted [2]. The communicating author of that study was contacted and reported no evidence of a difference between patients who had undergone OGJ (33 patients) and LGJ (9 patients), therefore justifying the combination of these two patient groups for the purposes of our analysis. Subgroup analysis was not attempted for the site of the primary tumour or stent type due to limited availability of data.

For the purposes of this study we defined oral intake as the ability to tolerate at least a liquid diet, which represented a common denominator for all studies and an appropriate marker of clinical success. This definition also applies to our measure of mean time to tolerating an oral intake.

Statistical methodology

All statistical calculations and forest plots were produced using Review Manager version 5.0.12 (Revman, Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen). Where source studies had reported median and range instead of mean and variance, we estimated their mean and variance based on the median, range and sample size according to the methods described by Hozo et al. [10]. Data for studies where the mean and variance were not obtainable were excluded from the analysis.

Odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for dichotomous variables using the Mantel–Haenszel method and a random-effects model. Weighted mean differences with 95% CI were calculated for continuous variables, using an inverse variance method and a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was calculated using a chi-squared test. A significance level of p < 0.05 was considered statistically relevant for outcome and heterogeneity measures.

Forest plots were constructed for number of patients tolerating an oral intake, mean time to tolerating an oral intake, length of hospital stay, length of survival and mortality at 30 days.

Results

In total, 13 studies met the criteria for inclusion in the review [2–4, 11–20]. These included 10 retrospective cohort comparison studies, two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and one prospective cohort comparison study (Table 1). No studies comparing ES versus OGJ or LGJ were excluded.

Outcome data for a total of 514 patients were included. The characteristics of each of the studies are displayed on Table 1. One RCT looked exclusively at ES versus LGJ [3]; the other 12 studies looked at ES versus either OGJ or LGJ. Between the ES and GJJ (OGJ and LGJ combined) groups, males were 1.5 times more likely to have received ES than females (OR 1.58 [5], p = 0.03). Mean age was similar between ES and GJJ (p = 0.48). The site of the primary tumour was pooled for all studies and is displayed in Table 2.

Endoscopic stenting versus open gastrojejunostomy

A total of 12 studies reported data comparing ES versus OGJ. From these studies, 244 patients were treated with ES and 218 patients with OGJ (the latter figure includes nine patients receiving LGJ who could not be distinguished; see “Methods”).

Ability to tolerate an oral intake was reported in 11 studies. Patients were more likely to tolerate an oral intake following ES than after OGJ (OR 2.62; CI: 1.17, 5.86; p = 0.02; Fig. 1).

Mean time to oral intake was reported in nine studies, of which six provided sufficient information for analysis (see “Methods”). Patients were more likely to tolerate an oral diet earlier following ES than with OGJ (mean difference 7 days; CI: 8.75, 5.02 days; p < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Length of hospital stay was reported in 12 studies, of which nine provided sufficient information for analysis. Patients were more likely to be discharged from hospital sooner following ES than with OGJ (mean difference 12 days; CI: 15.65, 7.94 days; p < 0.001; Fig. 3).

Length of survival was reported in 10 studies, of which four provided sufficient information for analysis. There was no significant difference in the length of survival following ES than with OGJ (mean difference 26 days; CI: –69.03, 16.40 days; p = 0.23; Fig. 4).

Mortality at 30 days was reported in nine studies. There was no significant difference in mortality at 30 days for patients undergoing ES versus OGJ (OR 0.83; CI: 0.32, 2.18; p = 0.71; Fig. 5).

Comparison of procedure time was reported in only two studies and could not be compared statistically. Maetani et al. [11] found that on average it took 30 min for ES and 118 min for OGJ (p < 0.0001), while Fiori et al. [18] found that the average operating times were 40 and 93 min, respectively (p < 0.0001) [11, 18].

Major complications were reported in 12 studies. There were no significant differences in the rates of major complications between patients undergoing ES versus OGJ (OR 1.04; CI: 0.47, 2.29; p = 0.93). However, patients undergoing OGJ suffered more major medical complications such as respiratory tract infections, myocardial infarction and acute renal failure. In patients undergoing ES the majority of the complications were procedure related (surgical or technical), including stent fracture, migration and obstruction (Table 3). Wound infections were more common in patients undergoing OGJ (ten) compared with ES (zero).

Significant heterogeneity in all outcomes was noted.

Endoscopic stenting versus laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy

A total of three studies reported data comparing ES with LGJ. These studies could not be quantitatively compared due to the small total number of procedures reported. A summary analysis was therefore undertaken (Table 4).

Overall, ES demonstrated significant benefits across a range of outcomes when compared with LGJ. Mehta et al. [3] showed that ES resulted in a shorter length of hospital stay [5.2 days, standard deviation (SD) 1.1 days] compared with LGJ (11.4 days, SD 2.4 days) (p = 0.02) and fewer complications (zero and eight patients, respectively) [3]. In the study by Mittal et al. [4], ES resulted in a shorter time to tolerating an oral intake (0 and 4 days, respectively) and a shorter length of hospital stay (2 and 7 days, respectively), although with a decreased length of survival (56 and 119 days, respectively) [4].

Discussion

This review has demonstrated improved outcomes with ES over OGJ for the palliation of symptoms associated with malignant GOO and thereby potentially improved quality of life. Patients undergoing ES are more likely to tolerate an earlier oral intake (average 7 days) and leave hospital earlier (average 12 days) with a comparable complication rate (average 15–16%). These benefits for ES were demonstrated without a significant increase in 30-day mortality or decrease in length of survival.

In terms of complications, it was found that OGJ resulted in substantially more major medical complications such as respiratory tract infection, myocardial infarction and acute renal failure. ES complications, by contrast, usually related to technical factors leading to the need for repeat intervention rather than major morbidity. Although there were similar rates of overall complications, the spectrum of complications suffered by the two groups was therefore shown to favour patients undergoing ES.

There was inadequate data available to evaluate the potential cost savings from ES over OGJ, particularly because there is much heterogeneity in the way that these costs have been measured in past studies. However, it is anticipated that significant cost savings would arise in favour of ES, directly from both the procedural costs and from the substantial reduction in hospital stay, as well as indirectly from the reduced procedural time and from resulting improvements in staff productivity [4, 14, 16, 17]. However, these potential savings may be at least partly offset by potentially higher rates of re-intervention among ES patients (discussed below), and it would therefore be beneficial if future studies formally reported the cost differences between the treatments in greater detail.

There was insufficient data in the literature to perform an analysis comparing LGJ with OGJ or ES. Based on currently available data, ES appears to provide some benefit with respect to shorter time to tolerating an oral intake and shorter time to hospital discharge compared with LGJ. When compared with OGJ, Jeurnink et al. found that LGJ (33 OGJ versus 9 LGJ) appeared to be more favourable in terms of tolerating an oral intake, length of hospital stay and the rate of complications, but found no statistical difference between the two (Jeurnink SM, Personal communication, 2008). Navarra et al. published a randomised controlled trial in 2005 comparing LGJ with OGJ in 24 patients (12 each) [21]. The study showed that LGJ resulted in significantly less intraoperative blood loss, shorter time to tolerating solid food intake and lower rate of complications, but no evidence of a difference in the hospital stay post-operatively. Conversely, in a retrospective study published in 1998 by Bergamaschi et al., only intraoperative blood loss and hospital stay were significantly different (22 OGJ versus 9 LGJ) [22]. Variation in outcomes between these two studies is likely explained by their small sample sizes and therefore low power. A high rate of conversion to open surgery has also been noted in some LGJ studies [23]. Overall, these studies support the observation that LGJ is now the preferred standard for the operative management of GOO, although additional randomised controlled studies would be beneficial to further validate this opinion [5].

Our findings are consistent with a previous meta-analysis published by Hosono et al. [8] which compared fewer patients (154 ES versus 153 OGJ from 9 studies, compared with 244 ES versus 218 OGJ from 12 studies here) [8]. Hosono et al. found less-marked improvements with respect to restarting an oral intake (5.4 days difference) and length of hospital stay (9.7 days difference), but no evidence of a difference in the rate of complications or in mortality at 30 days. Hosono et al. did not comment on the length of survival or compare the costs of the procedures.

An important limitation of this study was the necessary decision to restrict our analysis of outcomes, and especially complications, to a 30-day post-procedure window. Few data were available on longer-term outcomes for these patients. With longer follow-up it might be expected that ES patients would have greater rates of re-intervention due to late tumour in-growth and stent migration. The need for repeat stenting due to these events would decrease the benefits attributed to ES, especially in terms of cost. In a systematic review of ES and GJJ, for example, Jeurnink et al. found a higher rate of recurrent obstructive symptoms (18% after ES versus 1% for GJJ) for the ES group, and therefore concluded that GJJ may remain the preferable procedure in patients with a longer expected duration of survival [9]. The predominance of technical complications following ES found in this study supports this observation. However other factors must also be considered before more definitive guidelines can be developed. It is likely, for example, that the relative longer-term benefits of ES and OGJ would depend on the different types of malignancy responsible for GOO, due to differing durations of survival. Stent technology and palliative oncology therapies are also important and evolving research areas of relevance to this question. In particular, ongoing advances in stent design may be expected to reduce long-term stent failure, challenging any potential benefits for OGJ in patients with a longer duration of survival [24].

Both Jeurnink et al. and Mittal et al. reported shorter length of survival in patients undergoing ES compared with OGJ. This finding was not supported by the present review, but it should be noted that only four out of ten studies could be used to answer this question [4, 12, 15, 17]. In non-randomised retrospective cohorts, such as most of those evaluated here, patient selection bias is likely to be significant. For example, clinicians may select more advanced cases or patients with greater co-morbidities (and thus higher operative risk) to undergo ES, decisions that will translate to changes in survival duration when the treatments are compared. Data were also unavailable on the primary site of obstruction, which as stated above, may influence length of survival as patients with pancreatic or biliary malignancies may have reduced survival compared with other groups [25].

We found few RCTs in the published literature for inclusion in this review and therefore used cohort studies, which are less than optimal because of their potential for bias. Significant heterogeneity was, for example, noted between studies for all major outcomes reported here. This likely reflects differences between the patient populations in terms of the site or stage of the primary tumour, and specific treatment details such as the types of stents used, surgical or endoscopic expertise and the way in which outcomes were reported. In addition, neither of the RCTs identified in this review contributed to measurement of the primary outcomes.

Research questions that still remain include subpopulations who may still benefit from OGJ such as those with longer expected duration of survival, or whether ES with improved stent technology becomes the superior option. Additionally, patients may be discovered to have irresectable disease with GOO only after resection has been surgically attempted, presenting a choice between on-table ES or OGJ. Future studies might confirm whether the benefits of ES extend to this particular scenario.

In conclusion, this study suggests improved outcomes for ES over OGJ, and therefore palliative patients with malignant GOO may be better palliated with ES when compared with OGJ. However, there was insufficient data to make an adequate comparison between ES and LGJ, which is now widely believed to be the preferred operative standard for the treatment of malignant GOO. Furthermore, as the use of cohort studies is highly susceptible to bias, it is impossible to ensure that current estimates regarding the relative efficacy of these interventions are valid. Further well-designed RCTs are therefore necessary to validate the findings of this review.

References

Lopera FE, Brazzini A, Gonzales A, Castaneda-Zuniga WR (2004) Gastroduodenal stent placement: current status. Radiographics 24(6):1561–1573

Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, Van ‘T Hof G, Van Eijck CHJ, Kuipers EJ et al (2007) Gastrojejunostomy versus stent placement in patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction: a comparison in 95 patients. J Surg Oncol 96(5):389–396

Mehta S, Hindmarsh A, Cheong E, Cockburn J, Saada J, Tighe R et al (2006) Prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy versus duodenal stenting for malignant gastric outflow obstruction. Surg Endosc 20(2):239–242

Mittal A, Windsor J, Woodfield J, Casey P, Lane M (2004) Matched study of three methods for palliation of malignant pyloroduodenal obstruction. Br J Surg 91(2):205–209

Al-Rashedy M, Dadibhai M, Shareif A, Khandelwal MI, Ballester P et al (2005) Laparoscopic gastric bypass for gastric outlet obstruction is associated with smoother, faster recovery and shorter hospital stay compared with open surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 12(6):474–478

Adler D (2007) Enteral stents for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: testing our mettle. Gastrointest Endosc 66(2):361–363

Siddiqui A, Spechler SJ, Heurta S (2007) Surgical bypass versus endoscopic stenting for malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: a decision analysis. Dig Dis Sci 52(1):276–281

Hosono S, Ohtani H, Arimoto Y, Kanamiya Y (2007) Endoscopic stenting versus surgical gastroenterostomy for palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol 42(4):283–290

Jeurnink SM, Van Eijck CHJ, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD (2007) Stent versus gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol 7(18):1–10

Hozo PS, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I (2005) Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 5(13):1–10

Maetani I, Akatsuka S, Ikeda M, Tada T, Ukita T, Nakamura Y et al (2005) Self-expandable metallic stent placement for palliation in gastric outlet obstructions caused by gastric cancer: a comparison with surgical gastrojejunostomy. J Gastroenterol 40(10):932–937

Maetani I, Tada T, Ukita T, Inoue H, Sakai Y, Nagao J (2004) Comparison of duodenal stent placement with surgical gastrojejunostomy for palliation in patients with duodenal obstructions caused by pancreaticobiliary malignancies. Endoscopy 36(1):73–78

Del Piano M, Ballare M, Montino F, Todesco A, Orsello M, Magnani C et al (2005) Endoscopy or surgery for malignant GI outlet obstruction? Gastrointest Endosc 61(3):421–426

El-Shabrawi A, Cerwenka H, Bacher H, Kornprat P, Schweiger J, Mischinger HJ (2006) Treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstruction: endoscopic implantation of self-expanding metal stents versus gastric bypass surgery. Eur Surg 38(6):451–455

Wong YT, Brams DM, Munson L, Sanders L, Heiss F, Chase M et al (2002) Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to pancreatic cancer. Surg Endosc 16(2):310–312

Yim HB, Jacobson BC, Saltzman JR, Johannes RS, Bounds BC, Lee JH et al (2001) Clinical outcome of the use of enteral stents for palliation of patients with malignant upper GI obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc 53(3):329–332

Johnsson E, Thune A, Liedman B (2004) Palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction with open surgical bypass or endoscopic stenting: clinical outcome and health economic evaluation. World J Surg 28(8):812–817

Fiori E, Lamazza A, Volpino P, Burza A, Paparelli C, Cavallaro G et al (2004) Palliative management of malignant antro-pyloric strictures. Gastroenterostomy vs. endoscopic stenting. A randomized prospective trial. Anticancer Res 24(1):269–272

Mejia A, Ospina J, Munoz A, Albis R, Oliveros R (2006) Palliation of a malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. Rev Col Gastroenterol 21(1):17–21

Espinel J, Sanz O, Vivas S, Jorquera Munoz F, Olcoz JL et al (2006) Malignant gastrointestinal obstruction: endoscopic stenting versus surgical palliation. Surg Endosc 20(7):1083–1087

Navarra G, Musolino C, Venneri A, De Marco ML, Bartolotta M (2006) Palliative antecolic isoperistaltic gastrojejunostomy: a randomized controlled trial comparing open and laparoscopic approaches. Surg Endosc 20(12):1831–1834

Bergamaschi R, Marvik R, Thoresen JEK, Ystgaard B, Johnsen G, Myrvold HE (1998) Open versus laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy for palliation in advanced pancreatic cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc 8(2):92–96

Nagy A, Brosseuk D, Hemming A, Scudamore C, Mamazza J (1995) Laparoscopic gastroenterostomy for duodenal obstruction. Am J Surg 169(5):539–542

Maire F, Hammel P, Ponsot P, Aubert A, O’Toole D, Hentic O et al (2006) Long-term outcome of biliary and duodenal stents in palliative treatment of patients with unresectable adenocarcinoma of the head of pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol 101(4):735–742

Kuhlmann KFD, De Castro SMM, Gouma DJ (2004) Surgical palliation in pancreatic cancer. Minerva Chir 59(2):137–149

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ly, J., O’Grady, G., Mittal, A. et al. A systematic review of methods to palliate malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Endosc 24, 290–297 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0577-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0577-1